Abstract

Background

Cognitive impairment and cerebrovascular pathology are both frequent with ageing. Cognitive impairment due to vascular pathology of the brain, termed vascular cognitive impairment (VCI), is one of the most frequent causes of cognitive impairment in elderly subjects. Thus far, VCI has no specific pharmacological treatment. Recent observational studies have suggested a protective effect of physical activity in cognition, but adequate randomised controlled trials (RCT) are lacking.

Methods

AFIVASC is a multi-centre randomised controlled trial, with a 6-month intervention treatment and an additional follow-up of 6 months, that aims to estimate the impact of 6 months of moderate intensity physical activity on cognition (the primary outcome) at 6 and 12 months in subjects with VCI. Participants are community dwellers with criteria for VCI without dementia or who have had previous stroke or transient ischaemic attack (TIA). Patients may be self-referred or referred from a medical appointment. After confirming the inclusion criteria, a run-in period of 1 month is conducted to access adherence; only after that are subjects randomly assigned (using a computerised program blinded to clinical details) to two groups (intervention group and best practice usual care group). The intervention consists of three physical activity sessions of 60 min each (two supervised and one unsupervised) per week. The primary outcome is measured by the presence or absence of decline in cognitive status. Secondary outcomes include changes in neuro-cognitive measures, quality of life, and functional and motor status. Primary and secondary outcomes are evaluated at 6 and 12 months by investigators blinded to both intervention and randomisation. A required sample size of 280 subjects was estimated. Statistical analyses will include regression analysis with repeated measures. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee for Health of Centro Hospitalar de Lisboa Norte (ref. no. 1063/13) and by the Ethics Committee for Health of Centro Hospitalar do Porto CHP (ref. no. 2016.055(049-DEFI/048-CES)).

Discussion

We aim to show whether or not moderate physical activity has a beneficial impact on cognition, quality of life, motor, and functional status in people with vascular cognitive impairment, and to generate new insights on the applicability of implementing physical activity in this specific population.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT03578614 July 6, 2018.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Cognitive impairment is frequently associated with ageing, and cerebral vascular pathology is one of its most frequent causes [1, 2]. Vascular cognitive impairment (VCI) includes a myriad of clinical conditions having cerebrovascular aetiology in common that ultimately leads to some degree of cognitive impairment. Cognitive impairment ranges from single domain impairment, behavioural changes and mild multi-domain impairments to dementia (the most severe stage, termed vascular dementia). Dementia is characterised by a compromise of several cognitive domains that leads to functional decline (either in the social, occupational or personal and family context) and loss in autonomy in performing activities of daily living of different complexity. In milder forms, cognitive impairment due to vascular aetiology can be difficult to diagnose since it may be expressed by symptoms which tend to be linked to ageing and not to memory impairment. Examples of these symptoms are reduced verbal or motor initiative, psychomotor slowness, difficulty in multi-tasking, difficulty in planning, sequencing and finalizing actions, or even behavioural manifestations only (shown as less interest in hobbies or usual activities, and irritability or distractibility). VCI is caused by a heterogeneous group of vessel disorders causing different types of vascular lesions in the brain, from subclinical small vessel disease (including white matter changes, lacunes, or microbleeds) to clinically overt stroke [1, 2].

There is no specific treatment for VCI, and pharmacological trials have thus far generated negative results [3, 4]. Therefore, in the absence of a cure, efforts should be made to improve research and intervention in vascular risk factors [4,5,6]. Physical activity has gained increasing interest as a non-pharmacological treatment for both primary prevention and for delaying evolution in cognitive impairments due to vascular disease. In animal studies, physical activity has been shown to produce several metabolic effects (increased expression of neurotransmitters, increased hippocampal cell proliferation and neurogenesis, increased antioxidant capacity, reduced inflammatory cytokines and oxidative stress, and improved mitochondrial functioning and vascular endothelial function), leading to better neuroplasticity [7]. In human functional and cerebral perfusion studies, physical activity was also associated with improvement in brain functioning [8].

The World Health Organization (WHO) (2010) [9] and the American College of Sports Medicine (2017) [10] have produced recommendations on physical activity. The associations of cardiovascular [11] and cerebrovascular diseases [12] also produced recommendations on physical activity for cardiac and for stroke patients, respectively. However, data on cognitive disorders are quite controversial. Recent observational studies suggested that physical activity could prevent the progression of VCI [13]. On the other hand, a recent review found no protective effect of physical activity in cognitive decline [14]. In the DAPA trial published recently, no beneficial effect was achieved with physical activity in patients with Alzheimer’s disease [15]. There have been intervention trials in patients at high vascular risk without previous stroke but, with the exception of one study [16] (which did not include VCI), no benefit was found [17, 18].

Given these contradictory findings, we lack a robust evidence base to recommend physical activity in VCI. Furthermore, there are no data on what type, intensity, and frequency of activity would be necessary to achieve long-term gains.

We aim to test, through a randomised controlled trial (RCT), if physical activity has a beneficial impact on VCI. We hypothesise that regular physical activity of moderate intensity for at least 6 months will improve cognitive impairment in subjects with cognitive impairment due to cerebrovascular pathology.

We also aim to evaluate the effect of physical activity on the quality of life, and on functional and motor status.

Objectives

The primary objective is to conduct an RCT to evaluate the effect of 6 months of physical activity on cognitive performance in subjects with VCI without criteria of dementia at inclusion. We aim to evaluate cognitive performance (as the primary outcome), and quality of life and motor performance and functional status (as secondary outcomes). Other objectives are to identify the determinants for the progression of cognitive decline and quality of life in a large Portuguese sample of subjects with VCI without dementia and also to evaluate the impact of the engagement in physical activities in both subjects and informants.

Methods/design

Design

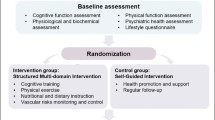

AFIVASC (“physical activity in vascular cognitive impairment’) is a Portuguese multi-centre, randomised parallel group trial comparing a 6-month intervention of two moderate physical activity sessions and one unsupervised moderate physical activity session per week with an additional follow-up of 6 months to evaluate its long-term impact in comparison with the current best practice usual care. The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement [19] has been used as a framework for the development of our methodology (Fig. 1). To ensure adherence, a run-in period will be conducted after inclusion. This run-in period consists of a 4-week period before randomisation during which all participants are assigned to equal procedures, namely the educational session and all planned assessments. After the run-in period, participants are randomised into two parallel groups (best practice usual care group and the intervention group). The best practice usual care group will receive the standard usual care, but they are allowed to perform physical activity by self-initiative, although supervised physical intervention is not allowed. The control of the amount of physical activity per week is performed in both groups through accelerometry. We do not expect to see high levels of physical activity in the usual care group since VCI is usually associated with a reduced initiative.

All participants will be followed up for 12 months. Informants (usually family members) are recruited, as is usual in cognitive studies, to provide additional data since we expect the sample size to decline over time. Participants, informants, and exercise physiologists are not blinded to the treatment, but all baseline and follow-up assessments (physical, neuropsychological, and radiological) are blinded to treatment allocation. According to data protection rules, all data are anonymised. Technicians involved in statistical analysis will be blinded to treatment allocation.

Participants

Recruitment and study setting

The study is conducted in the University of Lisbon at the Faculdade de Medicina and Instituto de Medicina Molecular in Lisbon, and the Hospital de Santo António, Centro Hospitalar do Porto. The Human Kinetics Faculty (from the University of Lisbon) is a partner of the study. These centres, both urban and academic, have experience in the diagnosis and management of patients with cognitive decline of a vascular aetiology and in stroke care. Subjects are referred to each participating centre directly from the community (participants can be self-presenting, as the study was advertised in public spaces) or from a medical appointment (general family doctor in primary care, or from neurological, mental health, memory clinics, or hospital settings). Participants can be referred to the study due to minor cognitive complaints/symptoms or minor behavioural changes attributed to a cerebrovascular aetiology. Patients can also be referred if they had a previous stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA), even without complaints, if neuropsychological evaluation showed evidence of any change considered to be due to a cerebrovascular aetiology. Post-stroke cognitive impairment is common even after successful clinical recovery from a stroke episode, and a recent study showed that at least one cognitive domain was impaired in 83% of cases [20]. Considering TIA, more than one cognitive domain was impaired in more than a third of patients 3 months after a TIA [21].

Eligible subjects are contacted by the recruitment team to further explain the procedures of the study and to confirm inclusion and exclusion criteria. Written informed consent is given by participants and informants. This consent allows access to the subject’s clinical records for research purposes and indicates their willingness to participate in all the activities inherent to the study. Those remaining eligible and without contraindications to physical activity are contacted by an investigator and proceed to baseline assessments.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria

Participants are included if they are 18 years and older and fulfil the following criteria: 1) provide written informed consent; 2) are fluent in the Portuguese language; 3) are able to read and write; 4) have an available, reliable informant; and 5) show clinical and functional criteria A and B as below.

Criteria A (any one of the following three):

-

1.

Probable mild cognitive vascular impairment (VCI, no dementia) [22];

-

2.

Previous ischaemic or haemorrhagic stroke (more than 6 months before), with modified Rankin score ≤ 2 at baseline and without formal indication for physiotherapy;

-

3.

TIA (more than 1 month before), diagnosed by a neurologist or with an identified vascular lesion (correlated with TIA clinical symptoms) in cerebral computed tomography (CT)/magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Criteria B: No functional changes, i.e. instrumental activity of daily living (IADL) scale = 0 (no item changed, or one single item with minimal change), according to the scoring methods of the LADIS study (minimum of four items applicable) [23] or no cognitive changes regarding the suggested Montreal Cognitive Assessment Test (MoCA) cut-off point for dementia in Portuguese clinical samples (score < 17) [24].

Exclusion criteria

Subjects cannot be included if they have at least one of the following: 1) a diagnosis of dementia; 2) stroke with formal indication for physiotherapy or speech therapy, or Rankin score ≥ 2; 3) any contraindication for walking, physical limitation to gait (orthopaedic or of other structural causes) that compromises physical activity, or other condition potentially interfering with the active treatment (e.g. severe arthritis or severe musculoskeletal pain associated with walking); 4) evidence of neurodegenerative disease (of aetiology other than vascular), severe mental disorder (e.g. major depressive episode or psychosis) or medical disease which could significantly interfere with the subjects’ participation or with their quality of life (e.g. cancer, congestive heart failure, or unstable angina).

Study outcomes

The primary outcome measure will be cognitive decline defined as a dichotomous variable (decline/no decline) through cognitive status criteria as described in the Assessments section below. The secondary outcomes are changes in neurocognitive scores of at least 1.5 standard deviation (SD) from baseline to endpoint (using z scores), a decline in the raw values of neuropsychological tests, in quality of life, functional and motor status, and falls.

Assessments

All participants attend three visits (baseline and two follow-up) consisting of clinical neuropsychological, physical, and functional observations (baseline, 6 months, and 12 months). The study schedule is shown in Fig. 2. In these visits, participants undergo the following assessments: 1) clinical and sociodemographic assessment; 2) physical activity assessment; 3) accelerometry assessment; 4) neuropsychological assessment; 5) and brain imaging (MRI scan; this only at baseline). Informants (appointed by participants as the best available person to provide information about them) are also interviewed.

In all assessments (baseline and follow-up clinical visits), the cognitive status of patients is classified into the following groups: 1) diagnosis of dementia; and 2) diagnosis of cognitive impairment with no dementia according to clinical, neuropsychological, and functional criteria. For this purpose, we used the usual criteria and definitions of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (edition 4 revised; DSM-4TR) [25]. At baseline, patients could only fulfil VCI without dementia defined as evidence of cognitive impairment and clinical consensus to identify significantly related vascular features; exclusion of dementia when impairments were not sufficiently severe to interfere with social or occupational functioning or when impairments were more focal than the global requirement for a diagnosis of dementia. For follow-up we considered the following criteria for subtypes of dementia: probable Alzheimer disease [26]; probable vascular dementia [27]; subtype of subcortical vascular dementia [28]; frontotemporal dementia [29]; and Lewy body dementia [30]. The criteria for Alzheimer’s disease with a vascular component was made when the investigator judged that the clinical picture presented both aspects of Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia.

Assessment measures

Participants are interviewed regarding sociodemographic factors relevant to the study subject and clinical factors, including cognitive status in a neurological assessment and functional status evaluation with the modified Rankin scale and the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) [31,32,33].

Neuropsychological and quality of life assessments

Cognitive evaluation follows the same protocol in all assessments and is applied by a trained neuropsychologist. It consists of a neuropsychological battery specifically designed for this study in order to be sensitive for vascular cognitive deficits and includes the following tests: The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) [34, 35] for general assessment; Letter cancellation [36] and the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised (WAIS-R) Digit Span (forward) [37, 38] for the assessment of attention and concentration; Verbal Fluency [35], Trail-Making Test [39,40,41], Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-3rd edition (WAIS-III), Digit-Symbol [42], and Stroop Test [43, 44] to assess executive functions; the California Verbal Learning Test-9 (CVLT-9) [45, 46], Wechsler Memory Scale (WMS) Visual Reproduction and Logical Memory subtests [36, 47], and WAIS-R Digit Span (backward) subtest [36, 37] to assess memory; and the Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale (ADAS) Naming objects and Following Commands subtests [48, 49] to assess language. The impact of cognitive performance on daily living activities is assessed with the Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) [50]; the presence of depressive symptoms and apathy are assessed using the 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale [51] and the Apathy Evaluation Scale [52, 53], respectively.

The quality of life and other specific measures for the assessment of an individual psychological resources and the economic impact of the disease are also added in this protocol. These measures include the Euro Qol-5 [54] and the Quality of Life in Alzheimer’s Disease (QOL-AD) [55, 56], the 13-item Orientation to Life Questionnaire to measure Antonovsky’s sense of coherence (SOC-13), a health-promoting resource which strengthens resilience where higher scores indicate an ability to adapt to stressful situations [57,58,59], the Successful Aging Index (SAI) [60], an a priori index model of successful ageing which was validated with respect to service use, and the Resources used in Dementia Interview (RUD) [61] to collect data on resource utilisation to calculate costs of care (healthcare resource utilisation) and time dedicated to caregiving in dementia.

Physical activity assessment

The Functional Physical Fitness Battery [62] is a simple, reproducible, readily available tool to assess submaximal functional capacity and to evaluate the response to intervention. The Six-Minute Walk Test (6MWT) is performed around an 18-m line to measure the distance in metres walked in 6 min. Participants are instructed to walk at their own pace according to their tolerance to exercise for 6 min, with rest stops as needed.

The 30-s chair stand assesses lower body strength, which is needed for numerous tasks such as climbing stairs or walking. Participants are instructed to sit and stand as fast as they can in 30 s with arms folded across the chest.

To assess lower body flexibility (which is important for good posture, normal gait patterns, and for various mobility tasks, such as getting in and out of a bathtub or car), the participant is asked to start from a sitting position at the front of the chair, with one leg extended and hands reaching toward the toes. The distance in centimetres between the extended fingers and the tip of the toe are measured in both legs. To assess upper body (shoulder) flexibility (which is important in tasks such as combing one’s hair, putting on overhead garments, and reaching for a seat belt), the participant is asked to reach over the shoulder with one hand and up the middle of the back with the other hand. The distance in centimetres between the extended middle fingers is measured.

The agility/dynamic balance is assessed by the number of seconds required to get up from a seated position, walk 2.44 m, turn, and return to the seated position. In this framework, it is interesting to measure multiple dimensions of balance in different sensory environments; therefore, the Fullerton Advanced Balance Scale (FAB) is also applied [63]. The FAB comprises 10 items that are scored using a 0–4 ordinal scale (only eight items are used due to safety and functional reasons). In this case, the highest score possible on the test is 32 points. Items include standing with the feet together and eyes closed, reaching forward to retrieve an object (a pencil) held at shoulder height with an outstretched arm, turn 360 degrees in both right and left directions, a tandem walk, standing on one leg, standing on foam with the eyes closed, a two-footed jump, and a walk with head turns.

Accelerometry assessment

The physical activity (PA) time of each participant is assessed by accelerometry (ActiGraph, GT3X+ model). The accelerometer is a device that measures the acceleration of normal human movements, ignoring high-frequency vibrations associated with mechanical equipment. All participants are asked to wear the accelerometer on the right hip, close to the iliac crest, for a week. The device activation, download, and processing is performed using Actilife v.6.13.3 software (ActiGraph, Fort Walton Beach, FL, USA). The devices are activated on the first day before the interview and data are recorded using the raw mode with a 30-Hz frequency and posteriorly downloaded into 15-s epochs.

A valid day is defined as having 600 min (10 h) or more of monitor wear and all participants with at least 3 valid days (including 1 weekend day) are included in the analyses. Accelerometer counts ≥ 100 counts per minute (cpm) are classified as PA with additional separation into light intensity (100–2019 cpm) and moderate-to-vigorous intensity (≥ 2020 cpm) [64, 65]. There are no cut-offs for the sedentary time using the three-axial information from this new generation Actigraph GT3X+ accelerometer; therefore, we used the previous cut-offs which are based on the vertical axis only. Compliance with PA recommendations for public health is assessed according to the WHO recommendations (adults: 150 min/week of at least moderate-to-vigorous intensity defined as ≥ 21.4 min/day).

Neuroimaging assessment

Besides confirming eligibility for the study, MRI is further used to control for confounders (for instance, information on the degree of atrophy, severity, number and localisation of vascular lesions, and presence of strategic lesions). MRI uses the following sequences: Fast Spin Echo, Fast Flair, T1 W-3EDGE (MPRAGE), diffusion and SWI, using a previously defined protocol based on the LADIS European study [66]. The parameters that are measured include:

-

1.

Atrophy (Scheltens evaluation, score 1–8 for global atrophy and 0–4 for temporal lobe atrophy) [67];

-

2.

White matter change evaluation using Modified Fazekas scale for severity (score 1–3) [68] and Scheltens scale for localisation of the lesions [67];

-

3.

Number and localisation of microbleeds (SWI sequences);

-

4.

Number and localisation of lacunes;

-

5.

Description of previous infarcts and intracerebral haemorrhages and silent infarcts.

MRI is conducted on the total sample at baseline. In all centres the MRI machine will have the same power (3 T).

To check for adhesion to the MRI protocol and the quality of scans, the performance of a dummy run will be required before the start of the study. For validation, the representative images of the dummy run will be checked centrally before start inclusion, and corrections will be made if necessary.

MRI will have a central reading, blinded to the clinical details, conducted by the responsible neuroradiologist. A clinical neurologist (JMF) not involved in the clinical assessment will also review the images blinded to the clinical results.

Run-in period and follow up assessments

The use of a pre-randomisation run-in period aims to ensure the engagement and adherence of subjects and to reduce bias associated with different levels of knowledge concerning expected benefits of the intervention. Over 4 weeks there is an educational group session, where the structure of the study, the benefits of physical activity, and the accelerometry report are explained.

Follow-up assessments will be conducted by clinicians (neurologist, neuropsychologist, and exercise physiologist not involved in the intervention sessions and blinded to the arm).

Randomisation and masking

After the 4-week run-in period, research personnel not involved in the recruitment, assessment, or intervention are responsible for managing the randomisation process using a statistical program. The randomisation sequence is generated by R software [69]. Participants are randomly assigned (1:1) to either the intervention group (IG) or to the best practice usual care group (CG), stratified by gender.

All follow-up assessments (physical, neuropsychological, and clinical diagnosis), and also the neuroradiological evaluation, are blinded to treatment allocation, as well as in the data set registry.

Intervention

Usual care

All participants receive usual care according to national guidelines. The Direção Geral da Saúde (DGS) only has guidelines for the elderly and not for subjects with VCI. In these guidelines, physical activity is recommended without further specification [70]. When clinically relevant problems are identified, the doctor in charge of the patient will be contacted for subsequent guidance.

Experimental intervention and implementation

In the intervention group, three physical activity sessions are planned per week (two supervised and one unsupervised) conducted over 6 months. In the first 2 months, the supervised sessions have 10 min of warm-up plus 5 min active pause (balance, agility, and coordinative exercises) plus 15 min walking plus 5 min active pause (resistance exercises, 1 series of 12 repetitions, three callisthenic exercises) plus 15 min walking plus 5 min flexibility (1 series of 10 s in three different postures). The aimed intensity in these first 2 months is 12/13. Between the second and fourth months, the duration of the walking period increases, as well as the intensity (rating of perceived exertion (RPE) 13/14). The session consists of 10 min of warm-up plus 5 min active pause (balance, agility, and coordinative exercises) plus 20 min walking plus 5 min active pause (resistance exercises, 1 series of 15 repetitions, three callisthenic exercises) plus 15 min walking plus 5 min flexibility (1 series of 10 s in three different postures). Between months 4 and 6, the duration of the walking period again increases, as well as the intensity (RPE 14/15). The session consists of 10 min of warm-up plus 5 min active pause (balance, agility, and coordinative exercises) plus 25 min walking plus 5 min of aerobic functional exercises (1 series of 15 repetitions, three callisthenic dynamic exercises) plus 20 min walking plus 5 min flexibility (1 series of 10 s in three different postures).

To measure the intensity level of the physical activity, the Borg rating of perceived exertion (RPE) ranging from 6 (rest) to 20 (maximum effort) is used [71]. Perceived exertion is how hard you feel your body is working. It is based on the physical sensations a person experiences during physical activity, including increased heart rate, increased respiration or breathing rate, increased sweating, and muscle fatigue. Although this is a subjective measure, a person’s exertion rating may provide a fairly good estimate of the actual heart rate during physical activity [71].

For the unsupervised session, participants are asked to accumulate at least 3 bouts of 10 min walking during the day, with the RPE according to their training intensity phase.

Regarding the best practise usual care group, physical activity counselling is given during the educational session before the randomisation based on their accelerometry results.

Intervention attendance and adherence

Intervention attendance within the 6 months is recorded in log sheets at the beginning of each session by the exercise physiologist responsible for the supervised physical activity sessions. For the unsupervised physical activity session, patients are asked in the second session of each week to report whether they have performed it or not. Dropouts are registered and, whenever the subjects allow, follow-up is maintained with the same design, although the subject cancels participation in the sessions.

Data management and safety

Data management follows the General Data Protection Regulation and the National Clinical Trial regulation (Act n° 21/2014, 16 April). Case report forms (CRFs) only include an anonymised code. Personal identification or any data leading to personal identification is not directly associated with data collection forms. The personal identification of subjects and data collection forms are stored in different locations of the leading centre, and data is only accessed by the research team.

Adverse events are registered in all scheduled appointments and reviewed by the exercise physiologist in all sessions. Adverse events are registered in the CRF. Serious adverse events are defined in the protocol as adverse events that require hospitalisation, medical interventions, or implicate significant disability, death, or are immediately life-threatening. These implicate referral to the doctor in charge, or to the emergency room if applicable. We should note that we do not expect to have relevant serious adverse effects, as the intervention follow WHO guidelines.

Study supervision and ethics

The Steering Committee includes the principal investigator (AV), the investigator leader in the second centre (MC), the leader in human kinetics (HSC), and the neuropsychologist expert leader (SM). Two independent members make up the data monitoring team (one an expert in statistics (ACS) and the other a clinician (HB)). Any protocol modifications are required to be submitted to the Ethical Committee after discussion within the Steering Committee. Dissemination of study results is planned both in scientific and in public sessions.

All procedures of the study and the CRFs, as well as the consent form, were approved by the Ethics Committee for Health of the Centro Hospitalar de Lisboa Norte (ref. no. 1063/13) and by the Ethics Committee for the Health of Centro Hospitalar do Porto CHP (ref. no. 2016.055(049-DEFI/048-CES)). As the intervention follows the WHO guidelines, the Ethical Committee did not consider it necessary to provide compensation in case of any incident during the study.

Statistics

Sample size

The sample size calculation is based on two sets of data. In the LADIS observational prospective study, which included a similar population [13], there was progression in cognitive decline in 31% of the initial sample after 1 year of follow-up (200 participants out of 639 participants included). In the Osaki-Tajiri Project [72], which studied conversion to dementia in a similar population and measured different severities of cerebrovascular pathology (as in our study), odds ratios (ORs) between 2.12 and 6 were found to be implicated in the conversion into vascular dementia. We used an OR of 4 in our calculation of the expected effect (which is clinically significant).

Using Open Epi software [73] for sample calculation in randomised trials, we realised a number of 117 subjects in each arm with 95% confidence intervals (alfa of 0.05) and 80% power, giving a total of 234 subjects to be recruited. Loss to follow-up is usually 20% in this type of follow-up study, and thus a total of 280 subjects is estimated as being needed.

Data analysis

Data will be registered according to the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines for randomised controlled trials [19]. We will use intention-to-treat analyses as the primary analysis with all participants included according to initial group allocation. For the primary outcome analysis (dependent variable: cognitive decline according to clinical criteria), we will conduct a logistic regression analysis. Since the outcomes are measured at 6 and 12 months, we will fit a generalised estimating equations (GEE) logistic regression model for the data. The models will adjust for covariates which are assumed to interfere with cognition in the follow-up (age, gender, education, and baseline MoCA). For secondary outcomes, logistic or linear regression analysis will be used as applicable.

For each of the outcome endpoints (i.e. transition of cognitive status and change in neuropsychological evaluation through composite or global scores) the change from baseline to 6 months and 12 months will be assessed, even though we will consider 12 months as the primary marker of success.

Observing a statistically significant difference on any of the outcomes will be considered preliminary evidence of efficacy. We will also report variances, co-variances, and effect sizes, as well as sampling feasibility (i.e. ease of recruitment, recruitment rate, withdrawal rate).

The same qualified statistician involved in the statistical analysis designed the SAP and will independently review the analysis according to the plan.

Discussion

There is considerable controversy concerning the impact of physical activity on the prevention of cognitive impairment of vascular aetiology. Most of the existing evidence is garnered from observational studies, with considerable heterogeneity of methods and types of interventions. Physical activity is currently recommended for the prevention of cardiovascular diseases and is already included in the European Guidelines of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation [11], but evidence in neurocognitive disorders is lacking. To the best of our knowledge, there are no previously published, high-quality parallel control trials on the effect of physical activity on the cognitive status of people with cognitive impairment due to cerebral vascular pathology. RCTs in other cognitive outcomes (for instance in Alzheimer’s disease) have generated controversial results [15]. In the recent DAPA trial [15], physical activity not only failed to improve cognitive status, but was associated with a mild (although not significant) cognitive deterioration. Regarding our study, we are aware of some limitations associated with the characteristics of any randomised controlled trial design, implying a selection of participants and exposure conditions that, in the end, may preclude generalisability. Nonetheless, in the absence of evidence-based interventions/treatments in vascular cognitive impairment, and considering that this is a highly prevalent pathology, we consider our study quite relevant. We believe that, in the field of neurocognitive disorders, vascular patients are more likely to benefit from physical interventions than patients with other neurodegenerative conditions. We also believe that if this study shows positive findings we will be able to deliver a simple and universal preventative treatment that can be widely disseminated in routine practice. At the same time, we are interested in determining the impact of physical activity on health-related quality of life and the motor and functional status of these patients, variables that have been understudied in this domain. Finally, we hope to explore the determinants of vascular cognitive impairment in Portuguese subjects.

References

Bowler JV, Hachinski V. Vascular cognitive impairment—a new concept. In: Bowler JV, Hachinski V, editors. Vascular cognitive impairment: preventable dementia. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2003. p. 321–37.

Hachinski V, Ladecola C, Petersen RC, Breteler MM, Nyenhuis DL, Black SE, et al. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke-Canadian Stroke Network vascular cognitive impairment harmonization standards. Stroke. 2006;37:2220–41.

Buckley JS, Salpeter SR. A risk-benefit assessment of dementia medications: systematic review of the evidence. Drugs Aging. 2015;32:453–67.

Dichgans M, Zietemann V. Prevention of vascular cognitive impairment. Stroke. 2012;43(11):3137–46.

Lincoln P, Fenton K, Alessi C, Prince M, Brayne C, Wortmann M, et al. The Blackfriars Consensus on brain health and dementia. Lancet. 2014;383:1805–6.

Dichgans M, Wardlaw J, Smith E, Zietemann V, Seshadri S, Sachdev P, et al. METACOHORTS for the study of vascular disease and its contribution to cognitive decline and neurodegeneration. An initiative of the Joint Programme for Neurodegenerative Disease research. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12:1235–49.

Gallaway PJ, Miyake H, Buchowski MS, Shimada M, Yoshitake Y, Kim AS, et al. Physical activity: a viable way to reduce the risks of mild cognitive impairment, Alzheimer's disease, and vascular dementia in older adults. Brain Sci. 2017;7:22.

Duzel E, van Praag H, Sendtner M. Can physical exercise in old age improve memory and hippocampal function? Brain. 2016;139:662–73.

World Health Organization. Global recommendations on physical activity for health. Genebra: WHO; 2010.

American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM’s guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. 10th ed. Baltimor, MD: Wolters Kluwer; 2017.

Perk J, De Backer G, Gohlke H, Graham I, Reiner Z, Verschuren M, et al. European Guidelines on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (version 2012): the Fifth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and other societies on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (constituted by representatives of nine societies and by invited experts). Eur Heart J. 2012;33:1635–701.

Gordon NF, Gulanick M, Costa F, Fletcher G, Franklin BA, Roth EJ, et al. Physical activity and exercise recommendations for stroke survivors. Stroke. 2004;35:1230–40.

Verdelho A, Madureira S, Ferro JM, Baezner H, Blahak C, Poggesi A, et al. Physical activity prevents progression for cognitive impairment and vascular dementia: results from the LADIS (Leukoaraiosis and Disability) study. Stroke. 2012;43(12):3331–5.

Guure CB, Ibrahim NA, Adam MB, Said SM. Impact of physical activity on cognitive decline, dementia, and its subtypes: meta-analysis of prospective studies. Biomed Res Int. 2017; Article ID 9016924, 13 pages.

Lamb SE, Sheehan B, Atherton N, Nichols V, Collins H, Mistry D, et al. Dementia and Physical Activity (DAPA) trial of moderate to high intensity exercise training for people with dementia: randomised controlled trial. The BMJ. 2018;361:k1675.

Ngandu T, Lehtisalo J, Solomon A, Levälahti E, Ahtiluoto S, Antikainen R, et al. A 2 year multidomain intervention of diet, exercise, cognitive training, and vascular risk monitoring versus control to prevent cognitive decline in at-risk elderly people (FINGER): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385:2255–63.

Ihle-Hansen H, Thommessen B, Fagerland MW, Øksengård AR, Wyller TB, Engedal K, et al. Multifactorial vascular risk factor intervention to prevent cognitive impairment after stroke and TIA: a 12-month randomized controlled trial. Int J Stroke. 2014;9(7):932–8.

Matz K, Teuschl Y, Firlinger B, Dachenhausen A, Keindl M, Seyfang L, et al. Multidomain lifestyle interventions for the prevention of cognitive decline after ischemic stroke: randomized trial. Stroke. 2015;46(10):2874–80.

Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D, for the CONSORT Group. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. Trials. 2010;11:32 (24 March 2010).

Jokinen H, Melkas S, Ylikoski R, Pohjasvaara T, Kaste M, Erkinjuntti T, et al. Post-stroke cognitive impairment is common even after successful clinical recovery. Eur J Neurol. 2015;22(9):1288–94.

Van Rooij FG, Schaapsmeerders P, Maaijwee NA, van Duijnhoven DA, de Leeuw FE, Kessels RP, et al. Persistent cognitive impairment after transient ischemic attack. Stroke. 2014;45(8):2270–4.

Gorelick PB, Scuteri A, Black SE, Decarli C, Greenberg SM, Iadecola C, et al. Vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2011;42:2672–713.

Verdelho A, Madureira S, Moleiro C, Ferro JM, Santos CO, Erkinjuntti T, et al. White matter changes and diabetes predict cognitive decline in the elderly: the LADIS study. Neurology. 2010;75:160–7.

Simões MR. Instrumentos de avaliação psicológica de pessoas idosas: investigação e estudos de validação em Portugal. RIDEP. 2012;34:9–33.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 2002.

McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's Disease. Neurology. 1984;34(7):939–44.

Román GC, Tatemichi TK, Erkinjuntti T, Cummings JL, Masdeu JC, Garcia JH, et al. Vascular dementia: diagnostic criteria for research studies. Report of the NINDS-AIREN International Workshop Neurology. 1993;43:250–60.

Erkinjuntti T, Inzitari D, Pantoni L, Wallin A, Scheltens P, Rockwood K, et al. Research criteria for subcortical vascular dementia in clinical trials. J Neural Transm Suppl. 2000;59:23–30.

McKhann GM, Albert MS, Grossman M, Miller B, Dickson D, Trojanowski JQ. Clinical and pathological diagnosis of frontotemporal dementia: report of the Work Group on Frontotemporal Dementia and Pick's Disease. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:1803–9.

McKeith IG, Galasko D, Kosaka K, Perry EK, Dickson DW, Hansen LA, et al. Consensus guidelines for the clinical and pathologic diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB): report of the consortium on DLB international workshop. Neurology. 1996;47:1113–24.

Rankin J. Cerebral vascular accidents in patients over age 60. Scott Med J. 1957;2:200–15.

Bamford JM, Sandercock PA, Warlow CP, Slattery J. Interobserver agreement for the assessment of handicap in stroke patients. Stroke. 1989;20(6):828.

Brott T, Adams HP Jr, Olinger CP, Marler JR, Barsan WG, Biller J, et al. Measurements of acute cerebral infarction: a clinical examination scale. Stroke. 1989;20(7):864–70.

Nasreddine Z, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, Charbonneau S, Whitehead V, Collin I, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695–9.

Freitas S, Simões MR, Martins C, Vilar M, Santana I. Estudos de adaptação do Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) para a população portuguesa. Aval psicol. 2010;9(3):345–57.

Garcia C: A Doença de Alzheimer: problemas do diagnóstico clínico. Tese de doutoramento. Faculdade de Medicina,Universidade de Lisboa; 1984.

Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised. New York: Psychological; 1981.

Cavaco S, Goncalves A, Pinto C, Almeida E, Gomes F, Moreira I, et al. Semantic fluency and phonemic fluency: regression-based norms of the Portuguese population. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2013;28:262–71.

Reitan RM. The validity of the Trail Making Test as an indicator of organic brain damage. Percept Mot Skills. 1958;8:271–6.

Cavaco S, Pinto C, Gonçalves A, Gomes F, Pereira A, et al. Trail Making Test: dados normativos dos 21 aos 65 anos. Psychologica. 2008;49:222–38.

Martins IP, Maruta C, Freitas V, Mares I. Executive performance in older Portuguese adults with low education. Clin Neuropsychol. 2013;27(3):410–25.

Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-III (Third edition). Nova York: Psychological Corporation; 1997.

Stroop JR. Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. J Exp Psychol. 1935;18:643–62.

Fernandes S. Adaptación del test de Colores y Palabras de Stroop en una Muestra Portuguesa—Influencia de la Reserva Cognitiva en la Función Ejecutiva de Sujetos Sanos y con Enfermedad Tipo Alzheimer de Inicio Tardio. Salamanca: Tese de Doutoramento apresentada à Universidade de Salamanca; 2009.

Libon DJ, Mattson RE, Glosser G, Kaplan E, Malamut BL, Sands LP, et al. A nine-word dementia version of the California Verbal Learning Test. Clin Neuropsychol. 1996;10(3):237–44.

Madureira S, Verdelho A, Ferro J, Basile AM, Chabriat H, Erkinjuntti T, et al. Development of a neuropsychological battery for the leukoaraiosis and disability in the elderly study (LADIS): experience and baseline data. Neuroepidemiology. 2006;27:101–16.

Wechsler D. Wechsler Memory Scale–Revised manual. San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation; 1987.

Rosen WG, Mohs RC, Davis KL. A new rating scale for Alzheimer's disease. Am J Psychiatr. 1984;141:1356–64.

Guerreiro, M., Fonseca, S., Barreto, J., & Garcia, C. Escala de Avaliação da Doença de Alzheimer (Alzheimer Disease Assessment Scale [ADAS]). In Alexandre de Mendonça, Manuela Guerreiro e Grupo de Estudos de Envelhecimento Cerebral e Demência (Eds.), Escalas e Testes na Demência (2.ª ed). Lisboa: Novartis. 2008;41-68.

Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. The Gerontologist. 1969;9(3):179–86.

Sheikh JI, Yesavage JA. Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) recent evidence and development of a shorter version. In: Brink TL, editor. Clinical gerontology: a guide to assessment and intervention. New York: The Haworth Press; 1986. p. 165–73.

Marin RS, Biedrzycki RC, Firinciogullari S. Reliability and validity of the Apathy Evaluation Scale. Psychiatry Res. 1991;38:143–62.

Caeiro L, Silva T, Ferro JM, Pais-Ribeiro J, Figueira ML. Metric properties of the Portuguese version of the Apathy Evaluation Scale. Psicologia Saúde Doenças. 2012;13:266–82.

The EuroQoL Group. EuroQol—a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16:199–208.

Logsdon R, Gibbons LE, McCurry SM, et al. Quality of life in Alzheimer’s disease: patient and caregiver reports. J Ment Health Aging. 1999;5:21–32.

Bárrios H, Verdelho A, Narciso S, et al. Quality of life in patients with cognitive impairment: validation of the quality of life—Alzheimer’s disease scale in Portugal. Int Psychogeriatr. 2013;25(7):1085–96.

Antonovsky A. The structure and properties of the sense of coherence scale. Soc Sci Med. 1993;36(6):725–33.

Eriksson M, Lindström B. Antonovsky’s sense of coherence scale and the relation with health: a systematic review. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60:376–81.

Saboga-Nunes L. Sense of coherence: operationalization of a concept that determines mental health and quality of life / O sentido de coerência:operacionalização de um conceito que influencia a saúde mental e a qualidade de vida. Tese elaborada no âmbito do Curso de Mestrado em Saúde Pública, UN, Lisboa, 1999.

Cosco TD, Stephan BCM, Brayne C. Validation of an a priori, index model of successful aging in a population-based cohort study: the successful aging index. Int Psychogeriatr. 2015;27(12):1971–7.

Wimo A, Wetterholm AL, Mastey V, et al. Evaluation of the resource utilization and caregiver time in anti-dementia drug trials–a quantitative battery. In: Wimo A, Karlsson G, Jönsson B, Winblad B, editors. The health economics of dementia. London, UK: Wiley’s; 1998.

Rikli R, Jones CJ. Senior Fitness Test manual. Champaign: Human Kinetics; 2001.

Rose DJ. Fallproof: a comprehensive balance and mobility program. Champaign: Human Kinetics; 2003.

Troiano RP, Berrigan D, Dodd KW, Mâsse LC, Tilert T, McDowell M. Physical activity in the United States measured by accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40(1):181–8.

Colley R, Connor Gorber S, Tremblay M. Quality control and data reduction procedures for accelerometry-derived measures of physical activity. Health Rep. 2010;21(1):63–9.

Poggesi A, Pantoni L, Inzitari D, et al. 2001-2011: a decade of the LADIS (Leukoaraiosis And DISability) Study: what have we learned about white matter changes and small-vessel disease? Cerebrovasc Dis. 2011;32(6):577–88.

Scheltens P, Leys D, Barkhof F, et al. Atrophy of medial temporal lobes on MRI in "probable" Alzheimer's disease and normal ageing: diagnostic value and neuropsychological correlates. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1992;55(10):967–72.

Fazekas F, Chawluk JB, Alavi A, et al. MR signal abnormalities at 1.5 T in Alzheimer's dementia and normal aging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1987;149(2):351–6.

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2016. https://www.r-project.org

Gambôa A, Leitão A, Silva AMS, Cádima C, Nunes E, Imperatori E, et al: Programa Nacional para a Saúde das Pessoas Idosas. Lisboa: Direcção-Geral da Saúde 2006, 250(1-2) 175-182.

Borg G. Borg's perceived exertion and pain scales. Champaign: Human Kinetics; 1998. p. 104.

Meguro K1, Ishii H, Kasuya M, et al. Incidence of dementia and associated risk factors in Japan: The Osaki-Tajiri Project. J Neurol Sci. 2007;260:175-82.

Dean AG, Sullivan KM, Soe MM. OpenEpi: open source epidemiologic statistics for public health, version. www.OpenEpi.com, updated 2013/04/06, accessed 2018/09/12.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Paulo Nicola for statistical advice.

Funding

The authors disclose receipt of the following financial support for this research: FCT (FCT-PTDC/DTP-ES/3706/2014).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AV, SM, MGP, ACS, PV, JMF, HSC, and MC conceived the study and participated in the design of the study. ACS was responsible for the statistical analysis plan. ACS and HB monitored the data. PV performed the MRI assessment. PV and JF reviewed neuroimaging, blinded to the clinical data. MR and SM are responsible for the neuropsychological assessment. MB is responsible for giving the intervention sessions. MG was involved in the physical evaluation of the patients at baseline. All authors read, edited the manuscript, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Ethic Committee for Health from the Centro Hospitalar de Lisboa Norte (CHLN) (ref. no. 1063/13) (Refª DIRCLN-11ABR2014–144) and the Ethic Committee for Health from the Centro Hospitalar do Porto (CHP) (ref. no. 2016.055(049-DEFI/048-CES) approved the study. This study adheres to the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT) guidelines, and the SPIRIT checklist is provided as Additional file 1.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects before participation in the study.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

SPIRIT 2013 checklist: recommended items to address in a clinical trial protocol and related documents. (DOC 121 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Verdelho, A., Madureira, S., Correia, M. et al. Impact of physical activity in vascular cognitive impairment (AFIVASC): study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 20, 114 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-019-3174-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-019-3174-1