Abstract

Background

As an increasing number of deaths occur in the intensive care unit (ICU), studies have sought to describe, understand, and improve end-of-life care in this setting. Most of these studies are centered on the patient’s and/or the relatives’ experience. Our study aimed to develop an instrument designed to assess the experience of physicians and nurses of patients who died in the ICU, using a mixed methodology and validated in a prospective multicenter study.

Methods

Physicians and nurses of patients who died in 41 ICUs completed the job strain and the CAESAR questionnaire within 24 h after the death. The psychometric validation was conducted using two datasets: a learning and a reliability cohort.

Results

Among the 475 patients included in the main cohort, 398 nurse and 417 physician scores were analyzed. The global score was high for both nurses [62/75 (59; 66)] and physicians [64/75 (61; 68)]. Factors associated with higher CAESAR-Nurse scores were absence of conflict with physicians, pain control handled with physicians, death disclosed to the family at the bedside, and invasive care not performed. As assessed by the job strain instrument, low decision control was associated with lower CAESAR score (61 (58; 65) versus 63 (60; 67), p = 0.002).

Factors associated with higher CAESAR-Physician scores were room dedicated to family information, information delivered together by nurse and physician, families systematically informed of the EOL decision, involvement of the nurse during implementation of the EOL decision, and open visitation. They were also higher when a decision to withdraw or withhold treatment was made, no cardiopulmonary resuscitation was performed, and the death was disclosed to the family at the bedside.

Conclusion

We described and validated a new instrument for assessing the experience of physicians and nurses involved in EOL in the ICU. This study shows important areas for improving practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

As an increasing number of deaths occur in the intensive care unit (ICU), studies have sought to describe, understand, and improve end-of-life care in this setting [1,2,3,4,5]. Most of these studies are centered on the patient’s and/or the relatives’ experience and have permitted to highlight elements of care that need improvement. Fewer studies have evaluated the healthcare professionals’ experience and perception of dying and death. Whether in the hospital in general [6] or in the ICU in particular [4, 7,8,9,10], these studies show a discrepancy between physicians’ and nurses’ experience and perception of end-of-life care—the latter generally expressing less satisfaction concerning pain control and quality of discussions and decision-making.

Among end-of-life research projects, tools have been developed to evaluate the quality of dying and death in the ICU, such as the Quality Of Dying and Death (QODD) instrument [11]. Quality of dying and death is defined as “the degree to which a person’s preferences for dying and the moment of death agree with observations of how the person actually died as reported by others” [12]. The quality of dying and death is subjectively determined with multiple factors that influence its evaluation, including culture, type and stage of disease, social and, importantly, professional role in the dying experience. A study comparing QODD ratings by relatives and by healthcare professionals [9] shows that relatives and attending physicians give the most favorable ratings of death, while nurses and residents provide less favorable ratings. Significant differences between these groups are notable on items related to patient autonomy. However, this tool was designed and validated in the USA, where hospital and end-of-life culture, and physicians’, nurses’, relatives’, and patients’ roles are different than in Europe [4, 13].

Thus, the French CAESAR project aimed to develop an instrument to assess the experience of relatives of patients who died in the ICU as well as the experience of healthcare professionals, physicians, and nurses. The relatives’ instrument was validated in a previous publication and presents valuable psychometric properties [5]. This 15-item questionnaire covered the patient’s preferences and values, interactions with/around the patient, and family satisfaction. Relatives’ lower scores were associated with greater risks of anxiety and depression at 3 months; post-traumatic stress-related symptoms at 3, 6, and 12 months; and complicated grief at 6 and 12 months.

Here, our objective was to develop and validate two tools specifically designed to assess the overall experience of physicians and nurses caring for patients who died in the ICU. We used a mixed methodology to create the instrument that was then validated in a multicenter prospective study in 41 French ICUs.

Participants and methods

The study was approved by the institutional review board of the Paris-North Hospitals (IRB00006477, approval#11019), Paris 7 University. Informed consent was obtained from each relative before study inclusion.

Physicians and nurses were invited to participate and to complete the CAESAR tool on a voluntary basis. They received information about the study, and those who did not wish to participate could decline. No written consent was required.

Before inclusion of patients, in each participating center, the local investigator, together with the head nurse, completed a description of the ICU.

Development and validation of the CAESAR-P and CAESAR-N instruments

Development of the CAESAR instrument was described in a previous publication [5]. A 33-item questionnaire for physicians and nurses was validated in a multicenter prospective study conducted from July 2011 to July 2013 in 41 French ICUs belonging to the FAMIREA network. The 33 items fell into three domains: the patient (preparation for death, whole person concerns, symptoms, personal care, and treatment preferences), interactions with and around the patient (quality of communication between ICU team and the patient and between the ICU team and the relatives, particularly whether conflicts arose), and family needs and satisfaction.

In each ICU, the intensivist included consecutive adults who died after at least 48 h in the ICU and for whom the relatives had visited at least once. For each patient, the physician and the nurse in charge of the patient were asked to complete the instrument within 24 h after the death. At the end of the instrument, participants were also asked to complete information such as age, sex, years of experience in the ICU, and religious beliefs. As described elsewhere, relatives completed the tool 21 days after the patient’s death [5].

After full data completion, 7 investigators (4 physicians, 1 psychologist, 1 sociologist, and 1 biostatistician) for the physicians’ instrument (CAESAR-P), and 6 investigators (2 nurses, 1 physician, 1 psychologist, 1 sociologist and 1 biostatistician) for the nurses’ instrument (CAESAR-N), worked to reduce the instrument from 33 to 15 items, based on clinical relevance and item distribution, discrimination, and redundancy [5]. The remaining 15 items (Table 1) were analyzed to explore the psychometric characteristics of the instrument, among physicians and among nurses separately. The psychometric validation was conducted using two sets of instruments: those completed by healthcare professionals for patients included in the CAESAR study [5] as the learning cohort (derivation set), and those completed by healthcare professionals for patients who had the same inclusion criteria, but who were not included in the CAESAR study, as the reliability cohort (validation set). These data were recorded at the beginning of the study period before inclusion started in the CAESAR study. Briefly, factorial validity was assessed in the derivation set and validation set separately by determining the dimensional structure of the final 15-item CAESAR questionnaire. To this end, we used maximum likelihood factor analysis with varimax rotation. The number of factors was determined from the observation of the scree plots and value of simulations [14,15,16]. Internal consistency was deemed acceptable when Cronbach’s alpha [17] was in the 0.70–0.95 range [18]. For the final 15-item tool, the item scores (range 1–5) were summed to obtain a global score (15–75). Each item included a written description and a score on a 5-point scale: 1, traumatic; 2, painful; 3, difficult; 4, acceptable; and 5, comforting. As a result, if a clinician rates all questions at 1, his/her total score will be 15, reflecting an overall traumatic experience. If a clinician rates all questions at 5, his/her total score will be 75, reflecting a very positive experience. Based on these calculations, scores between 60 and 75 reflect an overall positive experience; scores lower than 45 reflect an overall negative experience; scores between 45 and 60 are considered intermediary, reflecting that some elements of the end-of-life process were experienced negatively.

We also collected ICU, healthcare professionals’, patients’, and end-of-life characteristics.

Job strain evaluation

Physicians’ and nurses’ job strain was evaluated using an instrument that explores three domains: job demand (3 questions), control (5 questions), and social support (4 questions) [19,20,21]. High job demand, low decision control, and poor social support were graded as high for a score at 2–3, at 3–5, and at 3–4, respectively. Global job strain score was considered high (i.e., job strain positive) if there were 2 or 3 positive items among high job demand, poor decision control, and poor social support.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the R 3.1 package with the “psy” package [22].

Quantitative data were described as median (25e–75e percentiles, i.e., interquartile range); comparisons between groups were tested using ANOVA test. Binary and categorical data were described as number and percentages. No imputation for missing data was performed. To assess the number of dimension identified in the survey, a principal component analysis and the corresponding scree plot were used. The cutoff was determined using a set of simulations that illustrated the amount of variance that may be expected by chance alone [14]. The number of factors over the simulations may be of interest. The internal consistency was assessed with the Cronbach alpha (95% bootstrap confidence interval), split-half, and composite reliability. The association between job strain results and CAESAR-P and CAESAR-N scores was assessed using ANOVA test, according to the 3 dimensions. The center effect on CAESAR-N and CAESAR-P scores was assessed using a mixed regression model. All statistical tests were two-sided, and p values of 0.05 or less were considered significant.

Results

Study population

Patients’, ICUs’, and management of end-of-life characteristics are summarized in Supplemental Table 1. Physician and nurses’ characteristics are summarized in Supplemental Table 2. Among the 4607 patients admitted to the 41 participating ICUs during the study period, 875 (19%) died, including 228 who met exclusion criteria, 104 for whom the opportunity for inclusion was missed, and 68 whose relatives refused participation [5]. For each of the remaining 475 (54%) patients, one relative was included. Within 24 h of the death, the physician and the nurse in charge of the patient completed the 33-item instrument as well as the job strain (completed only once during the study period).

CAESAR scores

Among the 475 patients included, 398 nurse scores and 417 physician scores were analyzed.

The response rates were 441/475 (92.8%) for nurses and 446/475 (93.9%) for physicians. Among these, respectively 398/441 (90.2%) and 417/446 (93.5%) were fully completed, allowing score calculation and analysis.

The median global CAESAR score was 62/75 (59; 66) for nurses and 64/75 (61; 68) for physicians; the proportion of surveys with scores higher than 60/75 were 248/398 (62.3%) for nurses and 313/417 (75.1%) for physicians. There was no center effect for nurses (p 0.28), but a center effect was detected for physicians’ scores (p < 0.001).

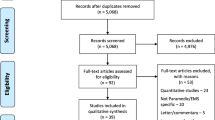

Supplemental Tables 3 and 4 depict the distribution of individual item scores for physicians and nurses, respectively. Figure 1 a and b depict the distribution of global scores for physicians and nurses, respectively. The factorial analysis of the main sample, assessed by scree plots, was consistent with a single dimension for both questionnaires, in the learning cohort and in the reliability cohort (Fig. 2a, b). Internal consistency was acceptable for both scales (Supplemental Tables 5 and 6).

Psychometric validation of the CAESAR-P and CAESAR-N. The factorial analyses and their corresponding scree plots are presented in a and b. In both cohorts and in both questionnaires, the first factor on its own explained a substantial amount of the item variance and no other factor appears of comparable importance, compared to the value of simulations. The scale is thus fairly homogeneous, if not strictly unidimensional

Factors associated with the CAESAR-P and the CAESAR-N scores

Physicians’ CAESAR-P score (Table 2) was higher when there was a room dedicated to family information, when the information was delivered together by nurse and physician, when families were systematically informed of the EOL decision rather than occasionally, when implementation of the EOL decision involved the nurse and physician rather than the physician only, and when the ICU was open 24 h/24 h. The physicians’ score was also higher when the patient had a McCabe score [23] at 1 rather than higher (i.e., no fatal expectancy); was not immunocompromised; had no dementia, liver failure, nor hematological disease; and did not require psychotropic medication. The score was higher when a decision to withdraw or withhold treatment was made, when no cardiopulmonary resuscitation was performed, and when the death was disclosed to the family at the bedside rather than by phone or upon arrival at the ICU.

The nurse CAESAR-N score (Table 2) was significantly higher in the absence of conflict with physicians, when pain control was handled by physicians rather than by nurses alone, when the death was disclosed to the family at the bedside rather than by phone or upon arrival at the ICU, and when invasive care such as surgery, chest tube, or bronchoscopy was not performed.

Job strain

Job strain was evaluated among 231 physicians and 379 nurses. Ten percent of physicians had a positive job strain. Among the 3 domains (job demand, decision control, and social support), the most frequent complaint for physicians was a high job demand (38.2%), but there was no association between the CAESAR score and job strain for physicians. Twenty-seven percent of nurses had a positive job strain. The most frequent complaint for nurses was a low decision control (54.2%) and a high job demand (44.5%). Low decision control was associated with lower CAESAR score for nurses (61 (58; 65) versus 63 (60; 67), p = 0.002).

Discussion

This multicenter study allowed us to develop and validate two 15-item CAESAR questionnaires (CAESAR-P and CAESAR-N) designed to measure self-reported experience of caregivers about patients’ end-of-life in the ICU, as we did previously for relatives [5].

Both tools (for nurses and for physicians) showed good internal consistency and a single dimension. The global score was high for both nurses [62/75 (59; 66)] and physicians [64/75 (61; 68)], reflecting global satisfaction regarding dying and death in the ICU, in keeping with previous studies [4, 24]. The nurses’ and the physicians’ results cannot however be strictly compared, as 2 questions differ between the two instruments.

Previous studies aiming at evaluating quality of dying and death [4, 9, 25] used the QODD, which was designed and validated in the USA, where hospital and end-of-life culture, and physicians’, nurses’, relatives’, and patients’ roles are different than in Europe. However, this tool has recently been used in Europe: in a study by Gerritsen et al. [25], the single-item QODD summary score was significantly higher for nurses in the Netherlands than in the USA, probably due to organizational (presence of a physician in the ICU and more often at the bedside in the Netherlands) and cultural differences.

In France, nurses’ perception of dying and death was evaluated over 10 years ago in hospitals [6] and in ICUs [7], showing poor ratings of quality of death and of end-of-life decisions. However, French legislation changed in 2005 and 2016, allowing withdrawing and withholding treatment, as well as palliative sedation, which has positively modified end-of-life culture in ICUs: our results are consistent with these improvements. In a more recent multicenter French study [24], nurses rated the end-of-life of their patients under mechanical ventilation at 8 on a scale from 1 (worst) to 10 (best), concordant with our findings. Research thus shows high rating of dying in the ICU, whether in Europe or the USA.

In our current study, nurses’ experience of the patient’s end-of-life in the ICU was worse in case of conflict with physicians. In a previous European study about ICU conflicts [20], end-of-life care was one of the main reported sources of conflict. In these situations, the principal sources of conflict were lack of psychological support, absence of unit-level meetings, and problems with the decision-making process. Two factors were associated with less conflict, i.e., symptom control performed jointly by physicians and nurses, and routine unit-level meetings. In our study, these two factors were also associated with a better experience of end-of-life for nurses (pain control handled by nurses rather than by physicians only, relatives’ information delivered together by nurse and physician) and for physicians (implementation of the end-of-life decision involving the nurse rather than the physician alone). Indeed high-quality end-of-life care requires good inter-professional collaboration and communication [26]. The job strain evaluation shows that for nurses, low decision control was associated with lower CAESAR score, highlighting the importance of valuing nurses’ involvement in decision-making processes. Physicians’ job strain was not associated with CAESAR score.

For both nurses and physicians, a better experience of end-of-life was associated with an absence of invasive care (considered aggressive in this setting): for nurses, absence of invasive care such as surgery, chest tube, or bronchoscopy; for physicians, decision to withhold or withdraw treatment, and absence of cardiopulmonary resuscitation—factors concordant with other study results [8, 9]. Absence of overaggressive treatment at the end-of-life can also be interpreted as a sign of good inter-professional communication as well as good communication with patients and family members [26, 27]. Early integration of palliative care that focuses on reducing suffering among patients with serious illness and their family members is recommended: in a study from the USA, nurse-assessed quality of dying was significantly improved with an intervention to integrate palliative care in the ICU [28].

Finally, good communication with family members and their presence in the ICU were associated with a better experience of patients’ end-of-life for nurses and physicians (communication at the bedside rather by phone, presence of a room dedicated to family information, systematic information of decision rather than occasional, open visiting hours) and are key elements in end-of-life care, as shown in previous studies [8, 25, 29]. Families are no longer simple visitors in the ICU: they play important roles and should now be considered by the ICU team as active partners, including in end-of-life situations [30].

This study has several limitations. First, all participating ICUs were in France and the findings may not be pertinent in different cultural settings. However, the large number of participating ICUs and clinicians, the very high response rate, and the validation of the results in a reliability cohort support the robustness of the data. Second, authors are aware of the potential issues with using an older dataset, specifically the potential changes of EOL practices across the world. However, use of the tool will permit to compare and describe changes across time and countries. Third, the global score was high in both groups of clinicians and the score differences were low and may not be meaningful to clinicians. However, this is true for other end-of-life tools used in Europe, such as the QODD [25]. Lastly, the description of the score on a 5-point scale (1, traumatic; 2, painful; 3, difficult; 4, acceptable; 5, comforting) raises a challenge in terms of measuring subjective responses. While pilot testing did not yield any difficulties between scoring on the scale, this is something to consider in future translations of this tool.

Conclusion

In summary, we described and validated two new instruments for assessing nurses’ and physicians’ experience of end-of-life in the ICU. Our study shows factors associated with a better experience that include quality communication, both with family members and inter-professional communication and collaboration; family presence in the ICU; and avoidance of aggressive care. These results will help design future interventional studies aimed at improving end-of-life care in the ICU.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable

References

Mularski R, Curtis JR, Osborne M, Engelberg RA, Ganzini L. Agreement among family members in their assessment of the Quality of Dying and Death. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2004;28(4):306–15.

Mularski RA, Heine CE, Osborne ML, Ganzini L, Curtis JR. Quality of dying in the ICU: ratings by family members. Chest. 2005;128(1):280–7.

Osborn TR, Curtis JR, Nielsen EL, Back AL, Shannon SE, Engelberg RA. Identifying elements of ICU care that families report as important but unsatisfactory: decision-making, control, and ICU atmosphere. Chest. 2012;142(5):1185–92.

Gerritsen RT, Hofhuis JGM, Koopmans M, van der Woude M, Bormans L, Hovingh A, Spronk PE. Perception by family members and ICU staff of the quality of dying and death in the ICU: a prospective multicenter study in the Netherlands. Chest. 2013;143(2):357–63.

Kentish-Barnes N, Seegers V, Legriel S, Cariou A, Jaber S, Lefrant JY, Floccard B, Renault A, Vinatier I, Mathonnet A, et al. CAESAR: a new tool to assess relatives’ experience of dying and death in the ICU. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42(6):995–1002.

Ferrand E, Jabre P, Vincent-Genod C, Aubry R, Badet M, Badia P, Cariou A, Ellien F, Gounant V, Gil R, et al. Circumstances of death in hospitalized patients and nurses’ perceptions: French multicenter Mort-a-l’Hopital survey. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(8):867–75.

Ferrand E, Lemaire F, Regnier B, Kuteifan K, Badet M, Asfar P, Jaber S, Chagnon JL, Renault A, Robert R, et al. Discrepancies between perceptions by physicians and nursing staff of intensive care unit end-of-life decisions. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167(10):1310–5.

Hodde NM, Engelberg RA, Treece PD, Steinberg KP, Curtis JR. Factors associated with nurse assessment of the quality of dying and death in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(8):1648–53.

Levy CR, Ely EW, Payne K, Engelberg RA, Patrick DL, Curtis JR. Quality of dying and death in two medical ICUs: perceptions of family and clinicians. Chest. 2005;127(5):1775–83.

Van Scoy LJ, Reading JM, Howrylak JA, Tamhane A, Sherman MS. Low quality of dying and death in patients with septic shock as perceived by nurses and resident physicians. Death Stud. 2016;40(8):486–93.

Engelberg RA, Patrick DL, Curtis JR. Correspondence between patients’ preferences and surrogates’ understandings for dying and death. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2005;30(6):498–509.

Patrick DL, Engelberg RA, Curtis JR. Evaluating the quality of dying and death. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2001;22(3):717–26.

Gerritsen RT, Jensen HI, Koopmans M, Curtis JR, Downey L, Hofhuis JGM, Engelberg RA, Spronk PE, Zijlstra JG. Quality of dying and death in the ICU. The euroQ2 project. J Crit Care. 2018;44:376–82.

Lance CE, Butts MM, Michels LC. The sources of four commonly reported cutoff criteria:what did they really say? Organ Res Methods. 2006;9(2):202–20.

Cattell RB. The scree test for the number of factors. Multivariate Behav Res. 1966;1(2):245–76.

Guttman L. Some necessary conditions for common-factor analysis. Psychometrika. 1954;19(2):149–61.

Cronbach LJ, Warrington WG. Time-limit tests: estimating their reliability and degree of speeding. Psychometrika. 1951;16(2):167–88.

JC N, IH B, J B: Psychometric theory. New York: McGraw- Hill; 1967.

Rusli BN, Edimansyah BA, Naing L. Working conditions, self-perceived stress, anxiety, depression and quality of life: a structural equation modelling approach. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:48.

Azoulay E, Timsit JF, Sprung CL, Soares M, Rusinova K, Lafabrie A, Abizanda R, Svantesson M, Rubulotta F, Ricou B, et al. Prevalence and factors of intensive care unit conflicts: the conflicus study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180(9):853–60.

Karasek R, Baker D, Marxer F, Ahlbom A, Theorell T. Job decision latitude, job demands, and cardiovascular disease: a prospective study of Swedish men. Am J Public Health. 1981;71(7):694–705.

Falissard B. Psy: various procedures used in psychometry. R package version 1.1; 2012. http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=psy. Accessed 1 Jan 2019.

McCabe WR, Jackson GG. Gram-negative bacteremia: I. etiology and ecology. Arch Intern Med. 1962;110(6):847–55.

Robert R, Le Gouge A, Kentish-Barnes N, Cottereau A, Giraudeau B, Adda M, Annane D, Audibert J, Barbier F, Bardou P, et al. Terminal weaning or immediate extubation for withdrawing mechanical ventilation in critically ill patients (the ARREVE observational study). Intensive Care Med. 2017;43(12):1793–807.

Gerritsen RT, Koopmans M, Hofhuis JG, Curtis JR, Jensen HI, Zijlstra JG, Engelberg RA, Spronk PE. Comparing quality of dying and death perceived by family members and nurses for patients dying in US and Dutch ICUs. Chest. 2017;151(2):298–307.

Curtis JR. Caring for patients with critical illness and their families: the value of the integrated clinical team. Respir Care. 2008;53(4):480–7.

Kentish-Barnes N, Azoulay E. End-of-life care in the ICU: semper ad meliora (always strive for improvement). Intensive Care Med. 2016;42(10):1653–4.

Curtis JR, Treece PD, Nielsen EL, Downey L, Shannon SE, Braungardt T, Owens D, Steinberg KP, Engelberg RA. Integrating palliative and critical care: evaluation of a quality-improvement intervention. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178(3):269–75.

Kentish-Barnes N, Chaize M, Seegers V, Legriel S, Cariou A, Jaber S, Lefrant JY, Floccard B, Renault A, Vinatier I, et al. Complicated grief after death of a relative in the intensive care unit. Eur Respir J. 2015;45(5):1341–52.

Davidson JE, Aslakson RA, Long AC, Puntillo KA, Kross EK, Hart J, Cox CE, Wunsch H, Wickline MA, Nunnally ME, et al. Guidelines for family-centered care in the neonatal, pediatric, and adult ICU. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(1):103–28.

Acknowledgements

These contributors participated to the study: Michel Badet, Chambéry Hospital, Chambéry, France; Julie Carr, Saint Eloi University Hospital, Montpellier, France; Sophie Cayot-Constantin, Estaing University Hospital, Clermont-Ferrand, France; Vincent Das, André Grégoire Hospital, Montreuil, France; Fabienne Fieux, Saint Louis University Hospital, Paris, France; Emmanuelle Hammad, Hôpital Nord University Hospital, Marseille, France; Mercé Jourdain, Roger Salengro University Hospital, Lille, France; Véronique Leray, La Croix Rousse Hospital, Lyon, France; Djamel Mokart, Institut Paoli Calmettes, Marseille, France; Sami Hraeich, Hôpital Nord University Hospital, Marseille, France; Michel Ramakers, Saint Lô Hospital, Saint Lô, France; Jean-Michel Robert, Edouard Herriot University Hospital, Lyon, France; and Antoine Roquilly, Hôtel Dieu University Hospital, Nantes, France.

Funding

Supported by a grant from the French Ministry of Health (PHRC 10 104)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.K.B. and E.A. designed the study. V.S. performed the statistical analysis. N.K.B., F.B., V.S., and E.A. made substantial contributions to the analysis and interpretation of data. F.B., V.S., and N.K.B. wrote the manuscript. All the authors had full access to all of the study data, contributed to drafting the manuscript or critically revised it for important intellectual content, approved the final version of the manuscript, and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. N.K.B. is the guarantor of the paper, taking responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, from inception to published article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the institutional review board of the Paris-North Hospitals (IRB00006477, approval#11-019), Paris 7 University. Informed consent was obtained from each relative before study inclusion.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

None of the authors declare any conflict of interest in relation to this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Supplemental Table 1.

Characteristics of ICU, end-of-life management and patients.

Additional file 2: Supplemental Table 2.

Characteristics of physicians and nurses.

Additional file 3: Supplemental Table 3.

Psychometric validation of the physician questionnaire: distribution of individual item scores.

Additional file 4: Supplemental Table 4.

Psychometric validation of the nurse questionnaire: distribution of individual item scores.

Additional file 5: Supplemental Table 5.

Psychometric validation of the physician questionnaire: Measurement error: internal consistency.

Additional file 6: Supplemental Table 6.

Psychometric validation of the nurse questionnaire: Measurement error: internal consistency.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Boissier, F., Seegers, V., Seguin, A. et al. Assessing physicians’ and nurses’ experience of dying and death in the ICU: development of the CAESAR-P and the CAESAR-N instruments. Crit Care 24, 521 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-020-03191-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-020-03191-z