Abstract

Background

Electroencephalography (EEG) is a well-established tool for assessing brain function that is available at the bedside in the intensive care unit (ICU). This review aims to discuss the relevance of electroencephalographic reactivity (EEG-R) in patients with impaired consciousness and to describe the neurophysiological mechanisms involved.

Methods

We conducted a systematic search of the term “EEG reactivity and coma” using the PubMed database. The search encompassed articles published from inception to March 2018 and produced 202 articles, of which 42 were deemed relevant, assessing the importance of EEG-R in relationship to outcomes in patients with impaired consciousness, and were therefore included in this review.

Results

Although definitions, characteristics and methods used to assess EEG-R are heterogeneous, several studies underline that a lack of EEG-R is associated with mortality and unfavorable outcome in patients with impaired consciousness. However, preserved EEG-R is linked to better odds of survival. Exploring EEG-R to nociceptive, auditory, and visual stimuli enables a noninvasive trimodal functional assessment of peripheral and central sensory ascending pathways that project to the brainstem, the thalamus and the cerebral cortex. A lack of EEG-R in patients with impaired consciousness may result from altered modulation of thalamocortical loop activity by afferent sensory input due to neural impairment. Assessing EEG-R is a valuable tool for the diagnosis and outcome prediction of severe brain dysfunction in critically ill patients.

Conclusions

This review emphasizes that whatever the etiology, patients with impaired consciousness featuring a reactive electroencephalogram are more likely to have a favorable outcome, whereas those with a nonreactive electroencephalogram are prone to having an unfavorable outcome. EEG-R is therefore a valuable prognostic parameter and warrants a rigorous assessment. However, current assessment methods are heterogeneous, and no consensus exists. Standardization of stimulation and interpretation methods is needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

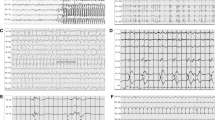

Electroencephalography (EEG) is a clinical neurophysiology tool used to evaluate cerebral cortex activity that possesses demonstrated efficacy for the diagnosis, monitoring, and prognosis of brain disorders in critically ill patients [1,2,3,4]. Guidelines of the International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology and the American Society of Clinical Neurophysiology provide standardized methods for EEG recording and analysis in intensive care unit (ICU) patients [1, 5,6,7]. EEG analysis relies mainly on the analysis of basic parameters such as the dominant frequency of background activity and its continuity, reactivity to stimuli, and the symmetry and occurrence of paroxysmal activities [1, 2, 8,9,10,11]. Many abnormal EEG patterns predict a poor outcome in critically ill patients [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23]. Several EEG scores have been described [2, 4, 22, 24,25,26]. Several studies point out that electroencephalographic reactivity (EEG-R) or the absence thereof was particularly useful for prognostication in patients with impaired consciousness [8, 27,28,29,30]. Although there is no consensus regarding the definition or the methods to use in assessing EEG-R, EEG-R could be defined as diffuse and transient changes in scalp recorded EEG activity in response to sensorial external stimuli. Such stimuli may be auditory (clapping and loudly calling the patient’s name), nociceptive (pinching of limbs or nipples, compression of the fingernails or of the periosteal surfaces of bones) [31], or visual (spontaneous or forced eye opening, intermittent photic stimulation) [29, 31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39]. The amplitude and/or frequency of EEG activity may change in response to external stimulation (Fig. 1). However, EEGs merely exhibiting stimuli-induced rhythmic, periodic, or ictal discharges [36] or muscle activity or eye blink artifacts are not considered as reactive by many authors [1, 5,6,7]. Because visual analysis of reactivity is prone to subjectivity [40,41,42], automated quantitative approaches have been proposed [37]. EEG-R to nociceptive, auditory, and/or photic stimulation requires the functional integrity of peripheral sensory pathways, the brainstem, subcortical structures, and the cerebral cortex. Absent EEG-R could therefore result from a severe dysfunction of any of these structures, precluding the cortical activation by the afferent somatosensory stimuli [43]. The importance of EEG-R in predicting patient outcome in postanoxic coma has been documented in many studies since the 1960s [14, 41, 44,45,46]. Lack of EEG-R has been shown to be of prognostic value in postanoxic, posttraumatic, or hepatic encephalopathies [3, 8, 16, 27,28,29, 47]. The present review highlights and discusses the mechanisms and particular usefulness of EEG-R for determining the prognosis of patients with impaired consciousness.

Example of a reactive electroencephalogram (EEG) following auditory stimulation (claps) of a patient with impaired consciousness. Upper: A 20-second epoch EEG sample showing a diffuse and synchronous slowing of the EEG background activity, appearing immediately after the auditory stimulus (claps) in an ICU patient with sepsis-associated encephalopathy. Recording: 20 mm/s, sensitivity: 10 μV/mm; filter settings: 0.5–70 Hz. Lower: EEG spectral power featuring topographic mapping of power of each main EEG frequency band (delta, theta, and alpha) computed 10 seconds before and 10 seconds after the auditory stimulus onset (claps). EEG changes from a theta-dominant frequency (before stimulation) into a delta-dominant one (after stimulation). Higher-power values are shown in warm colors, and cool colors depict lower power

Methods

We systematically searched the literature in the PubMed database for published reports pertaining to the use of EEG-R in outcome prediction in patients with impaired consciousness, from inception until March 2018, using the following search terms: (EEG reactivity OR electroencephalogram reactivity OR reactive EEG) AND (coma OR anoxic OR cerebral anoxia OR hypoxia OR post anoxic coma OR resuscitation OR cardiac arrest OR traumatic brain injury OR TBI OR encephalopathy OR unconscious OR vegetative state OR unresponsive wakefulness syndrome OR minimally conscious state) AND (outcome OR prognosis OR prognostication OR prediction OR predictive value OR mortality OR survival OR awakening). The search yielded 202 articles. Of these, we excluded non-English-language articles (n = 25) as well as those for which no full text was available (n = 28). Of the 149 remaining articles, we included 80 publications covering assessment of EEG-R and its impact on the prognosis of patients with impaired consciousness. Among these 80 publications were 17 review articles, 2 systematic reviews [32, 48], and 61 clinical investigation papers. We then carefully read and scrutinized all of these latter 61 articles.

Results

Data on the prognostic value of EEG-R in patients with impaired consciousness were explicitly reported in only 42 of the papers [8, 28, 30, 33, 37, 38, 44, 49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83] (see Table 1). Most studies in the present review assessed EEG within the first week following admission to the ICU or rehabilitation unit for postacute disorders of consciousness. EEG-R to external stimulation has emerged as an important predictor of improved outcome in a wide variety of clinical conditions [3, 8, 16, 27,28,29, 47], including traumatic brain injury (TBI) and anoxic brain injury [14, 16, 18, 72, 84]. Logi et al. [14] assessed the value of EEG-R in predicting consciousness recovery in 50 unconscious postacute brain injury patients. EEG patterns were ranked according to Synek’s classification [85]. EEG was reactive in 48% of the patients, and 92% of the patients with reactive EEG recovered consciousness within 5 months of EEG recording. Furthermore, multivariable analysis indicated that an unconscious patient admitted to the rehabilitation unit within 2 months from brain injury, with a Level of Cognitive Functioning Scale score equal to 2 and the presence of reactive EEG, had a probability of recovery of consciousness higher than 97%. They concluded that EEG-R had a high predictive value for the prognosis of recovery of consciousness in the postacute phase of brain injury, with a high specificity (88.9%). In 2015, Bagnato et al. [50] analyzed EEG predictors of outcome in 106 patients with disorders of consciousness admitted for intensive rehabilitation and found that mean Coma Recovery Scale–Revised (CRS-R) scores were lower in patients without EEG-R than in patients with EEG-R, at admission and after 3 months. Moreover, patients without EEG-R had less CRS-R score improvement after 3 months than patients with EEG-R [50]. More recently, the same team reported that in a group of 28 patients with unresponsive wakefulness syndrome, 16 patients exhibited improved consciousness at 6 months [33]. EEG-R at admission was absent in all patients devoid of improved consciousness. Additionally, only patients with improved consciousness exhibited a reappearance of EEG-R after 6 months [33].

In 1999, Kaplan et al. performed a retrospective analysis of the value of EEG-R to noxious stimuli for predicting outcome in 36 cases of alpha coma patients [44]. Fourteen of the 19 patients with nonreactive EEG died; 2 had support discontinued; and only 3 awoke. Kaplan et al. concluded that, although the cause of alpha coma largely predicted outcome, EEG-R predicted survival because most patients with EEG-R awoke, whereas most of those without EEG-R died [44]. Fernández-Torre et al. showed that in 26 patients with a diagnosis of postanoxic alpha coma, theta coma, or alpha-theta coma, EEG-R was associated with survival (p = 0.07) [57]. In 2009, Rossetti et al. found that postanoxic status epilepticus patients with favorable outcome exhibited preserved brainstem reflexes, cortical somatosensory evoked potentials (SSEPs), and reactive EEG background [18]. The same team demonstrated in 2010 that EEG background reactivity was useful in determining a prognosis in cardiac arrest survivors treated by therapeutic hypothermia [72]. In addition, median serum neuron-specific enolase peak values were higher in patients with nonreactive EEG background and discontinuous patterns, suggesting increased neuronal damage, and all subjects with nonreactive EEGs died [16]. Of the 36 patients studied by Ribeiro et al. [8], who had postanoxic encephalopathy showing generalized periodic epileptiform discharges on their first EEG, clinical characteristics between survivors and nonsurvivors did not significantly differ except for a trend toward significance for the presence of reactivity on the first EEG [71]. In our recent prospective study of 61 postanoxic patients with coma, the EEG was nonreactive in 48 patients, of whom 46 (95.8%) had an unfavorable outcome, defined as death, vegetative state, minimal conscious state, or severe disability [8]. We found that nonreactive EEG had a high sensitivity and specificity similar to those of the well-established Synek score for predicting an unfavorable outcome [3, 14, 15, 22, 84, 86, 87]. In accordance with Gilmore et al. [28], who showed that a lack of EEG-R was associated with mortality up to 1 year following discharge in ICU patients with sepsis, we recently found in a population of 110 patients with sepsis that ICU mortality was independently associated with the absence of EEG-R [27]. Furthermore, absence of EEG-R correlated with later development of in-ICU delirium. The absence of EEG-R and subsequent occurrence of delirium might be related to an impairment of cortical or brainstem function [88]. A possible role of sedation in the abolition of EEG-R may be hypothesized because administration of midazolam has been shown to increase the risk of delirium [89]. However, absence of EEG-R did not correlate with midazolam infusion rates or with the Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale score in our study. Conversely, unfavorable outcomes in patients who nevertheless present EEG responsiveness is also observed [14, 62]. This may be related to a lack of standardization of stimulations as previously discussed. Unfortunately, the procedure is rarely detailed in the literature.

The exact protocols and types of stimuli used for assessing EEG-R are quite heterogeneous, but three modalities of stimuli are used: the somesthetic modality, the auditory modality, and visual modality. Among the 42 studies in the present review, the 3 modalities were jointly tested in 15 (36%); both the somesthetic and auditory modalities were jointly tested in 14 (33%); 6 (14%) studies used only the somesthetic modality; and 3 (7%) studies used the visual modality alone. Stimulation modality was not described in four studies (10%). The visual modality is less frequently used, probably because the visual pathways are a little more difficult to assess in comatose patients compared with the auditory and somesthetic pathways. Johnsen et al. [37], systematically using all three stimulation modalities for EEG-R assessment, demonstrated that the nociceptive modality was the most effective type of stimulation (20.4%), followed by the auditory (8.7%) and visual (6.7%) modalities. Discrimination between good and poor outcomes was best in the theta and alpha bands for nociceptive stimulation in the first 10–20 seconds and for auditory stimulation in the first 5–10 seconds, whereas eye opening did not discriminate between good and poor outcomes [37]. This differential sensitivity between types of stimulation might be explained by high levels of noise and light in the ICU environment, rendering these two stimulation modalities less sensitive than nociceptive stimulation. However, Nita et al. demonstrated in a small group of five comatose children with acquired brain injury of various etiologies that intermittent photic stimulation performed at 1 Hz for 1 minute induced reactivity of the burst-suppression pattern and that standardized burst ratio reactivity appeared to reflect coma severity [38].

Discussion

Diffuse neurological failure, usually manifesting as coma and delirium, is a major determinant of mortality and morbidity in the ICU [90]. Lack of EEG-R correlated with mortality in patients with impaired consciousness [14, 16, 18, 72, 84]. Although there is no consensus regarding standardized methodology, EEG-R in patients with impaired consciousness is conventionally assessed through the application of two external stimuli: auditory and/or nociceptive stimulation [31], as well as, more rarely, passive eye opening and intermittent photic stimulation, both in adults [31, 33, 50] and in children [38]. The EEG is considered reactive when one of these stimulations modifies the amplitude and/or frequency of the background activity (Fig. 1) [1, 5,6,7]. Nonreactive EEG is characterized by no change in cerebral EEG activity after auditory and painful stimuli. Figure 2 features a nonreactive EEG following nociceptive stimulation in a postanoxic patient. EEG-R to auditory or painful stimuli can be seen as the modulation of the cortical activity following a peripherally applied stimulation. EEG-R to auditory stimuli requires the functional integrity of the peripheral and central auditory pathways involving the inner ear, the bulbopontine junction, the middle and upper parts of the pons, the midbrain (lateral lemniscus), the inferior colliculus, the medial geniculate nucleus of the thalamus, and the primary auditory cortex [91], whereas EEG-R to painful stimuli requires functional integrity of the pain projection pathways [92, 93] and the anterolateral system (Fig. 3) [94]. EEG-R to intense nociceptive and auditory stimuli indirectly tests the proper functioning of the somatosensory and auditory pathways of the brainstem and the cerebral cortex through two complementary modalities. In cases of severe cerebral impairment, the afferent nociceptive sensory or auditory impulses generated by the peripheral stimuli cannot reach the cerebral cortex, and EEG is therefore nonreactive. Critically ill patients are at risk of brain dysfunction induced not only by primary brain insults but also by neuroinflammation [95], ischemia secondary to microcirculatory dysfunction, and the neurotoxic effect of metabolic disturbance leading to impaired membrane excitability, neural conduction, and neural loss [96,97,98]. Impaired central auditory [99,100,101,102] and somatosensory [103,104,105] pathways have been documented by studies of evoked potentials to be associated with increased mortality in patients with impaired consciousness. Studies investigating the prognostic value of laser-evoked potentials and their correlation with EEG-R may be useful [106]. However, measuring laser-evoked potentials in the ICU is time-consuming compared with EEG. The brainstem controls many vital functions, including cardiocirculatory, respiratory, and arousal, through the ascending reticular activating system. Ascending monoaminergic and cholinergic activating systems localized in the upper brainstem, posterior hypothalamus, and basal forebrain release neurotransmitters, such as acetylcholine, norepinephrine, serotonin, histamine, and glutamate, and innervate the cerebral cortex, thalamus. They therefore have a widespread influence on forebrain function [107]. The brainstem also houses the autonomic nervous system’s main centers, which modulate immunity and systemic immune responses to aggression [108, 109]. Impaired EEG-R could therefore at least partly reflect a brainstem dysfunction in patients with impaired consciousness [110, 111]. EEG-R to visual stimulation (passive eye opening and intermittent photic stimulation) requires a functional integrity of the visual pathways from the retina to the occipital visual cortex, including the optic nerve, optic chiasm, optic tract, lateral geniculate nucleus, optic radiations, and striate cortex. A loss of EEG-R may reflect extensive damage to cortical or subcortical structures. Animal experiments have demonstrated that EEG-R is associated with the structural and functional integrity of the corticothalamic loop and thalamus-brainstem loop [112]. The thalamus is the key relay structure for ascending peripheral sensorial inputs (somesthetic, auditory, or visual) toward the cerebral cortex. The thalamus and its recurrent connections with the cortex play an integral role in the generation and sustenance of brain rhythms that underlie brain function as measured by EEG [113, 114]. The reticular nucleus of the thalamus (RN) surrounds the rostral and lateral surfaces of the dorsal thalamus. The RN contains exclusively GABAergic neurons and, via extensive inhibitory outputs, modulates all incoming sensory information on its way to the cerebral cortex [115]. The RN therefore plays a critical role in controlling the firing patterns of ventroposterior thalamic neurons and is thought to play a critical role in controlling thalamocortical rhythm [116]. The RN plays a crucial role in selective attention and consciousness because it can inhibit the area of the thalamus from which the initial information came and can influence the flow of information between the thalamus and cortex [117]. Increases in low-frequency cortical power may be due to a shift in thalamic neuron activity from a state dominated by tonic firing to one in which there is an increase in low-threshold spike burst firing [118]. Low-threshold calcium bursts occur when thalamocortical relay cells are in a state of hyperpolarization; there is evidence that the RN is capable of entertaining this “burst-firing mode” [119], and it is argued that the RN serves to maintain the low-frequency thalamocortical oscillations (4–10 Hz) [120, 121]. Aberrations and alterations in these thalamocortical loops is characteristic of several central nervous system disorders, particularly disorders of consciousness [122], because human perceptions arise from ongoing activity within recurrent thalamocortical circuits [123]. The lack of EEG-R observed in critically ill patients may result from altered modulation of thalamocortical loop activity by the afferent sensorial input due to the neural impairment [118]. This unresponsiveness of the thalamocortical rhythm’s synchronization or desynchronization [107, 113, 124] to sensorial stimuli reveals cerebral impairment and is strongly associated with patient outcome [14, 16, 18, 72, 84]. Moreover, the same EEG pattern may have a different prognostic value, depending on the presence or lack of EEG-R [44, 46, 125].

Example of a nonreactive electroencephalogram (EEG) following painful stimulus (pinching) in a patient with impaired consciousness. Upper: A 20-second epoch EEG sample showing generalized pseudoperiodic discharges of spikes with no change after the painful stimulus (pinching) in a postanoxic ICU patient. Recording: 20 mm/s, sensitivity: 10 μV/mm; filter settings: 0.50–70 Hz. Lower: EEG spectral power featuring topographic mapping of power of each main EEG frequency band (delta, theta, and alpha) computed 10 seconds before and 10 seconds after the painful stimulus. No significant EEG frequency band power change was observed after the painful stimulus. Higher-power values are shown in warm colors, and cool colors depict lower power

Schematic representation of pathways that convey somatosensory and auditory information to the cerebral cortex. The dorsal column-medial lemniscus system (solid black line), anterolateral-extralemniscal system (broken line), and auditory-lateral lemniscal system (orange colored solid line) are shown

Most studies of EEG-R do not mention the exact time at which reactivity was evaluated; however, it is well known that EEG features may change during the acute stage, especially in the first 24–48 hours after cardiac arrest [75, 126, 127]. The impact of the recovery of EEG-R on patient prognosis was recently demonstrated by Bagnato et al. [33], who reported that only patients with consciousness improvement showed the reappearance of EEG-R. Nine of the 16 patients with consciousness improvement, corresponding to 81.9% of patients who did not show EEG-R at admission, had reappearance of EEG-R at the 6-month follow-up. On the contrary, none of the patients without consciousness improvement showed reappearance of EEG-R. Repeated standard EEG or continuous EEG monitoring is then recommended in order to closely follow trends of the EEG changes in acute patients [27, 128,129,130].

It should be mentioned that EEG background activity and SSEPs are other neurophysiological parameters with robust outcome-predictive values in patients with impaired consciousness [1, 128, 131]. EEG background activity reflects spontaneous global cerebral functioning. It usually worsens by slowing down, decreasing amplitude, flattening, and discontinuing according to the severity of brain dysfunction [1, 5]. Worsened EEG background activity has been associated with unfavorable outcome in several studies [26, 75, 85, 130, 132]. Reduced EEG amplitudes and delta frequencies correlated with worse clinical outcomes, whereas alpha frequencies and reactivity correlated with better outcomes in patients with disorders of consciousness admitted for intensive rehabilitation [50]. Low-voltage or flat EEG background activity, burst suppression, and burst suppression with identical bursts are constantly associated with unfavorable outcome in postanoxic coma patients [75, 130, 132]. Spontaneously discontinuous background predicted unfavorable outcome with a false-positive rate of about 7% (95% CI, 0–24%) [16], whereas a continuous background predicted awakening with positive predictive values of 92% (95% CI, 80–98%) [133] and 72% (95% CI, 55–88%) [75]. SSEPs explore the functional integrity of the somatosensory pathways from the peripheral level to the cortical one through the brainstem and subcortical levels. The ability of absent SSEPs to detect patients at risk for poor neurological outcome appears to be robust [134]. Bilateral absent cortical components of SSEPs were associated with no awakening in anoxic coma, but normal SSEPs had less predictive capacity in the same cohort [135] because only 52% of patients with normal SSEPs awoke from coma [135]. In patients with TBI, normal SSEPs after TBI are associated with a 57% chance of good recovery, whereas bilateral absent SSEPs are associated with only a 1% chance of functional recovery [135, 136]. When combined with absent EEG-R, the prognostic value of SSEPs further increased [137]. Although there is no systematic study comparing the prognostic value of EEG background activity, SSEP, and EEG-R, available data and guidelines suggest that a combined multimodal assessment with these tests increases the accuracy of outcome prediction in patients with impaired consciousness [5, 128, 138,139,140].

Conclusions

This review emphasizes that whatever the etiology, patients with impaired consciousness featuring a reactive EEG are more likely to have favorable outcomes, whereas those with a nonreactive EEG are prone to unfavorable outcome. EEG-R is, then, a valuable prognostic parameter and warrants a rigorous assessment. However, current assessment methods are heterogeneous, and no consensus exists. Standardization of stimulation and interpretation methods is needed. Furthermore, it should be stated that all other EEG basic parameters, such as the dominant frequency or the continuity, warrant assessment in order to provide a fully integrated interpretation.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- aOR:

-

Adjusted OR

- BAEP:

-

Brainstem auditory evoked potential

- CA/H:

-

Cerebral anoxia/hypoxia

- cEEG:

-

Continuous electroencephalography

- CPC:

-

Cerebral Performance Categories scale

- CRS-R:

-

Coma Recovery Scale–Revised

- EEG:

-

Electroencephalography, electroencephalogram

- EEG-R:

-

Electroencephalographic reactivity

- GCS:

-

Glasgow Coma Scale

- GOS:

-

Glasgow Outcome Scale

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- LCFS:

-

Level of Cognitive Functioning Scale

- LOS:

-

Liverpool Outcome Score

- LR+:

-

Positive likelihood ratio

- mGOS:

-

Modified Glasgow Outcome Scale

- mRS:

-

Modified Rankin Scale

- NPV:

-

Negative predictive value

- NSE:

-

Neuron-specific enolase

- NT:

-

Normothermia

- PCOPCS:

-

Pediatric Cerebral and Overall Performance Category scale

- PCPC:

-

Pediatric Cerebral Performance Category scale

- PPV:

-

Positive predictive value

- RN:

-

Reticular nucleus of the thalamus

- SAH:

-

Subarachnoid hemorrhage

- Se:

-

Sensitivity

- Sp:

-

Specificity

- SSEP:

-

Somatosensory evoked potential

- TBI:

-

Traumatic brain injury

- TH:

-

Target therapeutic hypothermia

References

Guerit JM, Fischer C, Facco E, Tinuper P, Murri L, Ronne-Engstrom E, Nuwer M. Standards of clinical practice of EEG and EPs in comatose and other unresponsive states. The International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol Suppl. 1999;52:117–31.

Hockaday JM, Potts F, Epstein E, Bonazzi A, Schwab RS. Electroencephalographic changes in acute cerebral anoxia from cardiac or respiratory arrest. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1965;18:575–86.

Kaplan PW. The EEG in metabolic encephalopathy and coma. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2004;21(5):307–18.

Loeb C. Electroencephalograms during coma. Acta Neurochir. 1964;12:270–81.

Guerit JM, Amantini A, Amodio P, Andersen KV, Butler S, de Weerd A, Facco E, Fischer C, Hantson P, Jantti V, et al. Consensus on the use of neurophysiological tests in the intensive care unit (ICU): electroencephalogram (EEG), evoked potentials (EP), and electroneuromyography (ENMG). Neurophysiol Clin. 2009;39(2):71–83.

Hirsch LJ, LaRoche SM, Gaspard N, Gerard E, Svoronos A, Herman ST, Mani R, Arif H, Jette N, Minazad Y, et al. American Clinical Neurophysiology Society’s standardized critical care EEG terminology: 2012 version. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2013;30:1):1–27.

Nuwer MR, Comi G, Emerson R, Fuglsang-Frederiksen A, Guerit JM, Hinrichs H, Ikeda A, Luccas FJ, Rappelsberger P. IFCN standards for digital recording of clinical EEG. The International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol Suppl. 1999;52:11–4.

Azabou E, Fischer C, Mauguiere F, Vaugier I, Annane D, Sharshar T, Lofaso F. Prospective cohort study evaluating the prognostic value of simple EEG parameters in postanoxic coma. Clin EEG Neurosci. 2016;47(1):75–82.

Hirsch LJ, Kull LL. Continuous EEG monitoring in the intensive care unit. Am J Electroneurodiagnostic Technol. 2004;44(3):137–58.

Kuroiwa Y, Celesia GG. Clinical significance of periodic EEG patterns. Arch Neurol. 1980;37(1):15–20.

Milani P, Malissin I, Tran-Dinh YR, Deye N, Baud F, Levy BI, Kubis N. Prognostic EEG patterns in patients resuscitated from cardiac arrest with particular focus on generalized periodic epileptiform discharges (GPEDs). Neurophysiol Clin. 2014;44(2):153–64.

Bauer G, Trinka E, Kaplan PW. EEG patterns in hypoxic encephalopathies (post-cardiac arrest syndrome): fluctuations, transitions, and reactions. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2013;30(5):477–89.

Legriel S, Hilly-Ginoux J, Resche-Rigon M, Merceron S, Pinoteau J, Henry-Lagarrigue M, Bruneel F, Nguyen A, Guezennec P, Troche G, et al. Prognostic value of electrographic postanoxic status epilepticus in comatose cardiac-arrest survivors in the therapeutic hypothermia era. Resuscitation. 2013;84(3):343–50.

Logi F, Pasqualetti P, Tomaiuolo F. Predict recovery of consciousness in post-acute severe brain injury: the role of EEG reactivity. Brain Inj. 2011;25(10):972–9.

Roest A, van Bets B, Jorens PG, Baar I, Weyler J, Mercelis R. The prognostic value of the EEG in postanoxic coma. Neurocrit Care. 2009;10(3):318–25.

Rossetti AO, Carrera E, Oddo M. Early EEG correlates of neuronal injury after brain anoxia. Neurology. 2012;78(11):796–802.

Rossetti AO, Logroscino G, Liaudet L, Ruffieux C, Ribordy V, Schaller MD, Despland PA, Oddo M. Status epilepticus: an independent outcome predictor after cerebral anoxia. Neurology. 2007;69(3):255–60.

Rossetti AO, Oddo M, Liaudet L, Kaplan PW. Predictors of awakening from postanoxic status epilepticus after therapeutic hypothermia. Neurology. 2009;72(8):744–9.

Rundgren M, Westhall E, Cronberg T, Rosen I, Friberg H. Continuous amplitude-integrated electroencephalogram predicts outcome in hypothermia-treated cardiac arrest patients. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(9):1838–44.

Sethi N. EEG in anoxic coma. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2012;29(2):199. author reply 199–200

Sorensen K, Thomassen A, Wernberg M. Prognostic significance of alpha frequency EEG rhythm in coma after cardiac arrest. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1978;41(9):840–2.

Synek VM. Value of a revised EEG coma scale for prognosis after cerebral anoxia and diffuse head injury. Clin Electroencephalogr. 1990;21(1):25–30.

Yang Q, Su Y, Hussain M, Chen W, Ye H, Gao D, Tian F. Poor outcome prediction by burst suppression ratio in adults with post-anoxic coma without hypothermia. Neurol Res. 2014;36(5):453–60.

Haider I, Matthew H, Oswald I. Electroencephalographic changes in acute drug poisoning. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1971;30(1):23–31.

Silverman D. The EEG in anoxic coma. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1970;28(1):104.

Synek VM. Prognostically important EEG coma patterns in diffuse anoxic and traumatic encephalopathies in adults. J Clin Neurophysiol. 1988;5(2):161–74.

Azabou E, Magalhaes E, Braconnier A, Yahiaoui L, Moneger G, Heming N, Annane D, Mantz J, Chretien F, Durand MC, et al. Early standard electroencephalogram abnormalities predict mortality in septic intensive care unit patients. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0139969.

Gilmore EJ, Gaspard N, Choi HA, Cohen E, Burkart KM, Chong DH, Claassen J, Hirsch LJ. Acute brain failure in severe sepsis: a prospective study in the medical intensive care unit utilizing continuous EEG monitoring. Intensive Care Med. 2015;41(4):686–94.

Hermans MC, Westover MB, van Putten MJ, Hirsch LJ, Gaspard N. Quantification of EEG reactivity in comatose patients. Clin Neurophysiol. 2016;127(1):571–80.

Søholm H, Kjær TW, Kjaergaard J, Cronberg T, Bro-Jeppesen J, Lippert FK, Køber L, Wanscher M, Hassager C. Prognostic value of electroencephalography (EEG) after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in successfully resuscitated patients used in daily clinical practice. Resuscitation. 2014;85(11):1580–5.

Tsetsou S, Novy J, Oddo M, Rossetti AO. EEG reactivity to pain in comatose patients: importance of the stimulus type. Resuscitation. 2015;97:34–7.

Admiraal MM, van Rootselaar AF, Horn J. Electroencephalographic reactivity testing in unconscious patients: a systematic review of methods and definitions. Eur J Neurol. 2017;24(2):245–54.

Bagnato S, Boccagni C, Prestandrea C, Fingelkurts AA, Galardi G. Changes in standard electroencephalograms parallel consciousness improvements in patients with unresponsive wakefulness syndrome. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;98(4):665–72.

Grinspan ZM, Pon S, Greenfield JP, Malhotra S, Kosofsky BE. Multimodal monitoring in the pediatric intensive care unit: new modalities and informatics challenges. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2014;21(4):291–8.

Hilkman DM, van Mook WN, van Kranen-Mastenbroek VH. Continuous electroencephalographic-monitoring in the ICU: an overview of current strengths and future challenges. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2017;30(2):192–9.

Hirsch LJ, Claassen J, Mayer SA, Emerson RG. Stimulus-induced rhythmic, periodic, or ictal discharges (SIRPIDs): a common EEG phenomenon in the critically ill. Epilepsia. 2004;45(2):109–23.

Johnsen B, Nohr KB, Duez CHV, Ebbesen MQ. The nature of EEG reactivity to light, sound, and pain stimulation in neurosurgical comatose patients evaluated by a quantitative method. Clin EEG Neurosci. 2017;48(6):428–37.

Nita DA, Moldovan M, Sharma R, Avramescu S, Otsubo H, Hahn CD. Burst-suppression is reactive to photic stimulation in comatose children with acquired brain injury. Clin Neurophysiol. 2016;127(8):2921–30.

Tolonen A, Särkelä MOK, Takala RSK, Katila A, Frantzén J, Posti JP, Müller M, van Gils M, Tenovuo O. Quantitative EEG parameters for prediction of outcome in severe traumatic brain injury: development study. Clin EEG Neurosci. 2018;49(4):248–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/1550059417742232.

Gerber PA, Chapman KE, Chung SS, Drees C, Maganti RK, Ng YT, Treiman DM, Little AS, Kerrigan JF. Interobserver agreement in the interpretation of EEG patterns in critically ill adults. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2008;25(5):241–9.

Noirhomme Q, Lehembre R, del Rosario Lugo Z, Lesenfants D, Luxen A, Laureys S, Oddo M, Rossetti AO. Automated analysis of background EEG and reactivity during therapeutic hypothermia in comatose patients after cardiac arrest. Clin EEG Neurosci. 2014;45(1):6–13.

Young GB, McLachlan RS, Kreeft JH, Demelo JD. An electroencephalographic classification for coma. Can J Neurol Sci. 1997;24(4):320–5.

Altwegg-Boussac T, Schramm AE, Ballestero J, Grosselin F, Chavez M, Lecas S, Baulac M, Naccache L, Demeret S, Navarro V, et al. Cortical neurons and networks are dormant but fully responsive during isoelectric brain state. Brain. 2017;140(9):2381–98.

Kaplan PW, Genoud D, Ho TW, Jallon P. Etiology, neurologic correlations, and prognosis in alpha coma. Clin Neurophysiol. 1999;110(2):205–13.

Markand ON. Electroencephalography in diffuse encephalopathies. J Clin Neurophysiol. 1984;1(4):357–407.

Synek VM, Glasgow GL. Recovery from alpha coma after decompression sickness complicated by spinal cord lesions at cervical and midthoracic levels. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1985;60(5):417–9.

Jennett B, Bond M. Assessment of outcome after severe brain damage. Lancet. 1975;1(7905):480–4.

Sandroni C, Cavallaro F, Callaway CW, D’Arrigo S, Sanna T, Kuiper MA, Biancone M, Della Marca G, Farcomeni A, Nolan JP. Predictors of poor neurological outcome in adult comatose survivors of cardiac arrest: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Part 2: patients treated with therapeutic hypothermia. Resuscitation. 2013;84(10):1324–38.

Amantini A, Grippo A, Fossi S, Cesaretti C, Piccioli A, Peris A, Ragazzoni A, Pinto F. Prediction of ‘awakening’ and outcome in prolonged acute coma from severe traumatic brain injury: evidence for validity of short latency SEPs. Clin Neurophysiol. 2005;116(1):229–35.

Bagnato S, Boccagni C, Sant’Angelo A, Prestandrea C, Mazzilli R, Galardi G. EEG predictors of outcome in patients with disorders of consciousness admitted for intensive rehabilitation. Clin Neurophysiol. 2015;126(5):959–66.

Bisschops LL, van Alfen N, Bons S, van der Hoeven JG, Hoedemaekers CW. Predictors of poor neurologic outcome in patients after cardiac arrest treated with hypothermia: a retrospective study. Resuscitation. 2011;82(6):696–701.

Braksick SA, Burkholder DB, Tsetsou S, Martineau L, Mandrekar J, Rossetti AO, Savard M, Britton JW, Rabinstein AA. Associated factors and prognostic implications of stimulus-induced rhythmic, periodic, or ictal discharges. JAMA Neurol. 2016;73(5):585–90.

Claassen J, Hirsch LJ, Frontera JA, Fernández A, Schmidt M, Kapinos G, Wittman J, Connolly ES, Emerson RG, Mayer SA. Prognostic significance of continuous EEG monitoring in patients with poor-grade subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care. 2006;4(2):103–12.

Crepeau AZ, Rabinstein AA, Fugate JE, Mandrekar J, Wijdicks EF, White RD, Britton JW. Continuous EEG in therapeutic hypothermia after cardiac arrest: prognostic and clinical value. Neurology. 2013;80(4):339–44.

Duez CHV, Ebbesen MQ, Benedek K, Fabricius M, Atkins MD, Beniczky S, Kjaer TW, Kirkegaard H, Johnsen B. Large inter-rater variability on EEG-reactivity is improved by a novel quantitative method. Clin Neurophysiol. 2018;129(4):724–30.

Fantaneanu TA, Tolchin B, Alvarez V, Friolet R, Avery K, Scirica BM, O’Brien M, Henderson GV, Lee JW. Effect of stimulus type and temperature on EEG reactivity in cardiac arrest. Clin Neurophysiol. 2016;127(11):3412–7.

Fernández-Torre JL, López-Delgado A, Hernández-Hernández MA, Paramio-Paz A, Pía-Martínez C, Orizaola P, Martín-García M. Postanoxic alpha, theta or alpha-theta coma: clinical setting and neurological outcome. Resuscitation. 2018;124:118–25.

Gütling E, Gonser A, Imhof HG, Landis T. EEG reactivity in the prognosis of severe head injury. Neurology. 1995;45(5):915–8.

Howard RS, Holmes PA, Siddiqui A, Treacher D, Tsiropoulos I, Koutroumanidis M. Hypoxic-ischaemic brain injury: imaging and neurophysiology abnormalities related to outcome. QJM. 2012;105(6):551–61.

Juan E, Novy J, Suys T, Oddo M, Rossetti AO. Clinical evolution after a non-reactive hypothermic EEG following cardiac arrest. Neurocrit Care. 2015;22(3):403–8.

Kang XG, Li L, Wei D, Xu XX, Zhao R, Jing YY, Su YY, Xiong LZ, Zhao G, Jiang W. Development of a simple score to predict outcome for unresponsive wakefulness syndrome. Crit Care. 2014;18(1):R37.

Kang XG, Yang F, Li W, Ma C, Li L, Jiang W. Predictive value of EEG-awakening for behavioral awakening from coma. Ann Intensive Care. 2015;5(1):52.

Kessler SK, Topjian AA, Gutierrez-Colina AM, Ichord RN, Donnelly M, Nadkarni VM, Berg RA, Dlugos DJ, Clancy RR, Abend NS. Short-term outcome prediction by electroencephalographic features in children treated with therapeutic hypothermia after cardiac arrest. Neurocrit Care. 2011;14(1):37–43.

Lan YH, Zhu XM, Zhou YF, Qiu PL, Lu GP, Sun DK, Wang Y. Prognostic value of continuous electroencephalography monitoring in children with severe brain damage. Neuropediatrics. 2015;46(3):211–20.

Li F, Liu G, Tian X, Quan F, Li B, Feng G, Wang X, Hu Y. A novel scoring system to predict the outcomes of adult patients with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Expert Rev Neurother. 2018;18(4):343–50.

Li L, Kang XG, Qi S, Xu XX, Xiong LZ, Zhao G, Yin H, Jiang W. Brain response to thermal stimulation predicts outcome of patients with chronic disorders of consciousness. Clin Neurophysiol. 2015;126(8):1539–47.

Bastani A, Jaberzadeh S. Does anodal transcranial direct current stimulation enhance excitability of the motor cortex and motor function in healthy individuals and subjects with stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Neurophysiol. 2012;123(4):644–57.

Mohammad SS, Soe SM, Pillai SC, Nosadini M, Barnes EH, Gill D, Dale RC. Etiological associations and outcome predictors of acute electroencephalography in childhood encephalitis. Clin Neurophysiol. 2016;127(10):3217–24.

Oddo M, Rossetti AO. Early multimodal outcome prediction after cardiac arrest in patients treated with hypothermia. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(6):1340–7.

Ramachandrannair R, Sharma R, Weiss SK, Cortez MA. Reactive EEG patterns in pediatric coma. Pediatr Neurol. 2005;33(5):345–9.

Ribeiro A, Singh R, Brunnhuber F. Clinical outcome of generalized periodic epileptiform discharges on first EEG in patients with hypoxic encephalopathy postcardiac arrest. Epilepsy Behav. 2015;49:268–72.

Rossetti AO, Oddo M, Logroscino G, Kaplan PW. Prognostication after cardiac arrest and hypothermia: a prospective study. Ann Neurol. 2010;67(3):301–7.

Rossetti AO, Tovar Quiroga DF, Juan E, Novy J, White RD, Ben-Hamouda N, Britton JW, Oddo M, Rabinstein AA. Electroencephalography predicts poor and good outcomes after cardiac arrest: a two-center study. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(7):e674–82.

Rossetti AO, Urbano LA, Delodder F, Kaplan PW, Oddo M. Prognostic value of continuous EEG monitoring during therapeutic hypothermia after cardiac arrest. Crit Care. 2010;14(5):R173.

Sivaraju A, Gilmore EJ, Wira CR, Stevens A, Rampal N, Moeller JJ, Greer DM, Hirsch LJ, Gaspard N. Prognostication of post-cardiac arrest coma: early clinical and electroencephalographic predictors of outcome. Intensive Care Med. 2015;41(7):1264–72.

Steinberg A, Rittenberger JC, Baldwin M, Faro J, Urban A, Zaher N, Callaway CW, Elmer J. Neurostimulant use is associated with improved survival in comatose patients after cardiac arrest regardless of electroencephalographic substrate. Resuscitation. 2018;123:38–42.

Bachmann CG, Muschinsky S, Nitsche MA, Rolke R, Magerl W, Treede RD, Paulus W, Happe S. Transcranial direct current stimulation of the motor cortex induces distinct changes in thermal and mechanical sensory percepts. Clin Neurophysiol. 2010;121(12):2083–9.

Sutter R, Stevens RD, Kaplan PW. Significance of triphasic waves in patients with acute encephalopathy: a nine-year cohort study. Clin Neurophysiol. 2013;124(10):1952–8.

Thenayan EA, Savard M, Sharpe MD, Norton L, Young B. Electroencephalogram for prognosis after cardiac arrest. J Crit Care. 2010;25(2):300–4.

Topjian AA, Sanchez SM, Shults J, Berg RA, Dlugos DJ, Abend NS. Early electroencephalographic background features predict outcomes in children resuscitated from cardiac arrest. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2016;17(6):547–57.

Tsetsou S, Novy J, Pfeiffer C, Oddo M, Rossetti AO. Multimodal outcome prognostication after cardiac arrest and targeted temperature management: analysis at 36°C. Neurocrit Care. 2018;28(1):104–9.

Young GB, Kreeft JH, McLachlan RS, Demelo J. EEG and clinical associations with mortality in comatose patients in a general intensive care unit. J Clin Neurophysiol. 1999;16(4):354–60.

Zhang Y, Su YY, Haupt WF, Zhao JW, Xiao SY, Li HL, Pang Y, Yang QL. Application of electrophysiologic techniques in poor outcome prediction among patients with severe focal and diffuse ischemic brain injury. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2011;28(5):497–503.

Scollo-Lavizzari G, Bassetti C. Prognostic value of EEG in post-anoxic coma after cardiac arrest. Eur Neurol. 1987;26(3):161–70.

Synek VM. EEG abnormality grades and subdivisions of prognostic importance in traumatic and anoxic coma in adults. Clin Electroencephalogr. 1988;19(3):160–6.

Chen R, Bolton CF, Young B. Prediction of outcome in patients with anoxic coma: a clinical and electrophysiologic study. Crit Care Med. 1996;24(4):672–8.

Rothstein TL, Thomas EM, Sumi SM. Predicting outcome in hypoxic-ischemic coma. A prospective clinical and electrophysiologic study. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1991;79(2):101–7.

Gunther ML, Morandi A, Ely EW. Pathophysiology of delirium in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Clin. 2008;24(1):45–65.

Ely EW, Shintani A, Truman B, Speroff T, Gordon SM, Harrell FE Jr, Inouye SK, Bernard GR, Dittus RS. Delirium as a predictor of mortality in mechanically ventilated patients in the intensive care unit. JAMA. 2004;291(14):1753–62.

Ely EW, Inouye SK, Bernard GR, Gordon S, Francis J, May L, Truman B, Speroff T, Gautam S, Margolin R, et al. Delirium in mechanically ventilated patients: validity and reliability of the confusion assessment method for the intensive care unit (CAM-ICU). JAMA. 2001;286(21):2703–10.

Hashimoto I. Auditory evoked potentials from the human midbrain: slow brain stem responses. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1982;53(6):652–7.

Jang SH, Kwon YH, Lee MY, Lee DY, Hong JH. Termination differences in the primary sensorimotor cortex between the medial lemniscus and spinothalamic pathways in the human brain. Neurosci Lett. 2012;516(1):50–3.

Jang SH, Seo JP. Differences of the medial lemniscus and spinothalamic tract according to the cortical termination areas: a diffusion tensor tractography study. Somatosens Mot Res. 2015;32(2):67–71.

Jang SH, Kwon HG. Anatomical location of the medial lemniscus and spinothalamic tract at the pons in the human brain: a diffusion tensor tractography study. Somatosens Mot Res. 2013;30(4):206–9.

Mikacenic C, Hahn WO, Price BL, Harju-Baker S, Katz R, Kain KC, Himmelfarb J, Liles WC, Wurfel MM. Biomarkers of endothelial activation are associated with poor outcome in critical illness. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0141251.

Presneill JJ, Waring PM, Layton JE, Maher DW, Cebon J, Harley NS, Wilson JW, Cade JF. Plasma granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor levels in critical illness including sepsis and septic shock: relation to disease severity, multiple organ dysfunction, and mortality. Crit Care Med. 2000;28(7):2344–54.

Walser H, Emre M, Janzer R. Somatosensory evoked potentials in comatose patients: correlation with outcome and neuropathological findings. J Neurol. 1986;233(1):34–40.

Zauner C, Gendo A, Kramer L, Kranz A, Grimm G, Madl C. Metabolic encephalopathy in critically ill patients suffering from septic or nonseptic multiple organ failure. Crit Care Med. 2000;28(5):1310–5.

Facco E, Munari M, Baratto F, Behr AU, Giron GP. Multimodality evoked potentials (auditory, somatosensory and motor) in coma. Neurophysiol Clin. 1993;23(2–3):237–58.

Fischer C, Bognar L, Turjman F, Villanyi E, Lapras C. Auditory early- and middle-latency evoked potentials in patients with quadrigeminal plate tumors. Neurosurgery. 1994;35(1):45–51.

Kochar DK, Kumawat BL, Halwai M, Kochar SK, Shubhakaran, Thanvi I. Brainstem auditory evoked potentials and somatosensory evoked potentials in cerebral malaria—a prognostic significance. J Assoc Physicians India. 2000;48(3):295–300.

Schwarz G, Litscher G, Rumpl E, Pfurtscheller G, Reimann R. Brainstem auditory evoked potentials in respiratory insufficiency following encephalitis. Int J Neurosci. 1996;84(1–4):35–44.

Azabou E, Rohaut B, Heming N, Magalhaes E, Morizot-Koutlidis R, Kandelman S, Allary J, Moneger G, Polito A, Maxime V, et al. Early impairment of intracranial conduction time predicts mortality in deeply sedated critically ill patients: a prospective observational pilot study. Ann Intensive Care. 2017;7(1):63.

Del Felice A, Bargellesi S, Linassi F, Scarpa B, Formaggio E, Boldrini P, Masiero S, Zanatta P. The potential role of pain-related SSEPs in the early prognostication of long-term functional outcome in post-anoxic coma. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2017;53(6):883–91.

Zanatta P, Linassi F, Mazzarolo AP, Arico M, Bosco E, Bendini M, Sorbara C, Ori C, Carron M, Scarpa B. Pain-related Somato sensory evoked potentials: a potential new tool to improve the prognostic prediction of coma after cardiac arrest. Crit Care. 2015;19:403.

Naro A, Russo M, Leo A, Rifici C, Pollicino P, Bramanti P, Calabro RS. Cortical responsiveness to nociceptive stimuli in patients with chronic disorders of consciousness: do C-fiber laser evoked potentials have a role? PLoS One. 2015;10(12):e0144713.

Steriade M. Ascending control of thalamic and cortical responsiveness. Int Rev Neurobiol. 1970;12:87–144.

Pavlov VA, Tracey KJ. The vagus nerve and the inflammatory reflex—linking immunity and metabolism. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2012;8(12):743–54.

Tracey KJ. The inflammatory reflex. Nature. 2002;420(6917):853–9.

Rohaut B, Porcher R, Hissem T, Heming N, Chillet P, Djedaini K, Moneger G, Kandelman S, Allary J, Cariou A, et al. Brainstem response patterns in deeply-sedated critically-ill patients predict 28-day mortality. PLoS One. 2017;12(4):e0176012.

Sharshar T, Porcher R, Siami S, Rohaut B, Bailly-Salin J, Hopkinson NS, Clair B, Guidoux C, Iacobone E, Sonneville R, et al. Brainstem responses can predict death and delirium in sedated patients in intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2011;39(8):1960–7.

Kujala MV, Tornqvist H, Somppi S, Hanninen L, Krause CM, Vainio O, Kujala J. Reactivity of dogs’ brain oscillations to visual stimuli measured with non-invasive electroencephalography. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e61818.

Steriade M. Grouping of brain rhythms in corticothalamic systems. Neuroscience. 2006;137(4):1087–106.

Ploner M, Gross J, Timmermann L, Pollok B, Schnitzler A. Pain suppresses spontaneous brain rhythms. Cereb Cortex. 2006;16(4):537–40.

Pinault D. The thalamic reticular nucleus: structure, function and concept. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2004;46(1):1–31.

Fuentealba P, Steriade M. The reticular nucleus revisited: intrinsic and network properties of a thalamic pacemaker. Prog Neurobiol. 2005;75(2):125–41.

McAlonan K, Brown VJ. The thalamic reticular nucleus: more than a sensory nucleus? Neuroscientist. 2002;8(4):302–5.

Hughes SW, Crunelli V. Thalamic mechanisms of EEG alpha rhythms and their pathological implications. Neuroscientist. 2005;11(4):357–72.

Golshani P, Liu XB, Jones EG. Differences in quantal amplitude reflect GluR4-subunit number at corticothalamic synapses on two populations of thalamic neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(7):4172–7.

Maywood ES, Smith E, Hall SJ, Hastings MH. A thalamic contribution to arousal-induced, non-photic entrainment of the circadian clock of the Syrian hamster. Eur J Neurosci. 1997;9(8):1739–47.

Buzsaki G. The thalamic clock: emergent network properties. Neuroscience. 1991;41(2–3):351–64.

Min BK. A thalamic reticular networking model of consciousness. Theor Biol Med Model. 2010;7:10.

Jones EG, Hendry SH. Differential calcium binding protein immunoreactivity distinguishes classes of relay neurons in monkey thalamic nuclei. Eur J Neurosci. 1989;1(3):222–46.

Steriade M, McCormick DA, Sejnowski TJ. Thalamocortical oscillations in the sleeping and aroused brain. Science. 1993;262(5134):679–85.

Young GB, Blume WT, Campbell VM, Demelo JD, Leung LS, McKeown MJ, McLachlan RS, Ramsay DA, Schieven JR. Alpha, theta and alpha-theta coma: a clinical outcome study utilizing serial recordings. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1994;91(2):93–9.

Spalletti M, Carrai R, Scarpino M, Cossu C, Ammannati A, Ciapetti M, Tadini Buoninsegni L, Peris A, Valente S, Grippo A, et al. Single electroencephalographic patterns as specific and time-dependent indicators of good and poor outcome after cardiac arrest. Clin Neurophysiol. 2016;127(7):2610–7.

Tjepkema-Cloostermans MC, Hofmeijer J, Trof RJ, Blans MJ, Beishuizen A, van Putten MJ. Electroencephalogram predicts outcome in patients with postanoxic coma during mild therapeutic hypothermia. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(1):159–67.

Azabou E, Fischer C, Guerit JM, Annane D, Mauguiere F, Lofaso F, Sharshar T. Neurophysiological assessment of brain dysfunction in critically ill patients: an update. Neurol Sci. 2017;38(5):715–26.

Claassen J, Taccone FS, Horn P, Holtkamp M, Stocchetti N, Oddo M. Recommendations on the use of EEG monitoring in critically ill patients: consensus statement from the neurointensive care section of the ESICM. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39(8):1337–51.

Cloostermans MC, van Meulen FB, Eertman CJ, Hom HW, van Putten MJ. Continuous electroencephalography monitoring for early prediction of neurological outcome in postanoxic patients after cardiac arrest: a prospective cohort study. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(10):2867–75.

Rosenthal ES. The utility of EEG, SSEP, and other neurophysiologic tools to guide neurocritical care. Neurotherapeutics. 2012;9(1):24–36.

Hofmeijer J, Tjepkema-Cloostermans MC, van Putten MJ. Burst-suppression with identical bursts: a distinct EEG pattern with poor outcome in postanoxic coma. Clin Neurophysiol. 2014;125(5):947–54.

Hofmeijer J, Beernink TM, Bosch FH, Beishuizen A, Tjepkema-Cloostermans MC, van Putten MJ. Early EEG contributes to multimodal outcome prediction of postanoxic coma. Neurology. 2015;85(2):137–43.

Bouwes A, Binnekade JM, Zandstra DF, Koelman JH, van Schaik IN, Hijdra A, Horn J. Somatosensory evoked potentials during mild hypothermia after cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Neurology. 2009;73(18):1457–61.

Robinson LR, Micklesen PJ, Tirschwell DL, Lew HL. Predictive value of somatosensory evoked potentials for awakening from coma. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(3):960–7.

Houlden DA, Li C, Schwartz ML, Katic M. Median nerve somatosensory evoked potentials and the Glasgow coma scale as predictors of outcome in comatose patients with head injuries. Neurosurgery. 1990;27(5):701–7. discussion 707–8

Oddo M, Rossetti AO. Predicting neurological outcome after cardiac arrest. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2011;17(3):254–9.

André-Obadia N, Zyss J, Gavaret M, Lefaucheur JP, Azabou E, Boulogne S, Guérit JM, McGonigal A, Merle P, Mutschler V, et al. Recommendations for the use of electroencephalography and evoked potentials in comatose patients. Neurophysiol Clin. 2018;48(3):143–69.

Grippo A, Carrai R, Scarpino M, Spalletti M, Lanzo G, Cossu C, Peris A, Valente S, Amantini A. Neurophysiological prediction of neurological good and poor outcome in post-anoxic coma. Acta Neurol Scand. 2017;135(6):641–8.

Hantson P, de Tourtchaninoff M, Guerit JM, Vanormelingen P, Mahieu P. Multimodality evoked potentials as a valuable technique for brain death diagnosis in poisoned patients. Transplant Proc. 1997;29(8):3345–6.

Su YY, Wang M, Chen WB, Fu P, Yang QL, Li HL, Wang XM, Wang L. Early prediction of poor outcome in severe hemispheric stroke by EEG patterns and gradings. Neurol Res. 2013;35(5):512–6.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Azabou, E., Navarro, V., Kubis, N. et al. Value and mechanisms of EEG reactivity in the prognosis of patients with impaired consciousness: a systematic review. Crit Care 22, 184 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-018-2104-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-018-2104-z