Abstract

Hexavalent vaccines, protecting against six diseases (diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis [DTaP], poliovirus, hepatitis B virus [HBV], and Haemophilus influenzae type b [Hib], are routinely the standard of care in Europe. The use of combined vaccines allows the reduction of number of injections and side effects, the reduction of costs, and the increase in adherence of the family to the vaccination schedule both in terms of the number of doses and timing. The safety profile, efficacy and effectiveness of hexavalent vaccines have been extensively documented in infants and children born at term, and data are accumulating in preterm infants. Hexavalent vaccines are particularly important for preterm infants, who are at increased risk for severe forms of vaccine preventable diseases. However, immunization delay has been commonly reported in this age group. All the three hexavalent vaccines currently marketed in Italy can be used in preterm infants, and recent data confirm that hexavalent vaccines have a similar or lower incidence of adverse events in preterm compared to full-term infants; this is likely due to a weaker immune system response and reduced ability to induce an inflammatory response in preterm infants. Apnoea episodes are the adverse events that can occur in the most severe preterm infants and / or with history of respiratory distress. The risk of apnoea after vaccination seems to be related to a lower gestational age and a lower birth weight, supporting the hypothesis that it represents an unspecific response of the preterm infant to different procedures. High seroprotection rates have been reported in preterm infants vaccinated with hexavalent vaccine. However, a lower gestational age seems to be associated with lower antibody titres against some vaccine antigens (e.g. HBV, Hib, poliovirus serotype 1, and pertussis), regardless of the type of hexavalent vaccine used. Waiting for large effectiveness studies, hexavalent vaccines should be administered in preterm infants according to the same schedule recommended for infants born at term, considering their chronological age and providing an adequate monitoring for cardio-respiratory events in the 48–72 h after vaccination, especially for infants at risk of recurrence of apnoea.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In Italy, as well as in most European countries, hexavalent vaccines, protecting against six diseases (diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis [DTaP], poliovirus, hepatitis B virus [HBV], and Haemophilus influenzae type b [Hib]), are routinely the standard of care [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Combined vaccines allow the reduction of the number of injections and number of side effects, the reduction of costs and the increase in adherence of the family to the vaccination schedule both in terms of the number of doses and timing [7, 8]. As a consequence, in countries which have adopted a program based on hexavalent vaccines, the coverage rates in the first year of life are high (from 90 to 99%) and higher than those obtained in countries that use other multivalent vaccines as the only option or as an alternative to hexavalent vaccination (70–90%) [8]. According to the Italian 2017–2019 National Vaccine Prevention Plan (PNPV) schedule (Fig. 1), the primary immunization cycle with hexavalent vaccines includes 3 doses, to be administered at 3–5-11 months of age, followed by booster doses in preschool age (at 6 years) with DTPa and inactivated poliovirus vaccines (DTPa-IPV) and with dTaP-IPV in adolescents (12–18 years) and adults, to be repeated every 10 years [9]. This strategy has been associated with a dramatic reduction in the number of cases of infectious diseases targeted by the hexavalent vaccines in Italy [10]. Currently, three hexavalent vaccines are marketed in Italy, Infanrix Hexa®, Hexyon® and Vaxelis®, which can be administered in preterm infants. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) authorizes the use of the three hexavalent vaccines even in the most severe preterm infants ( [11,12,13] Fig. 2).

In term infants the three hexavalent vaccines have been proved to be not inferior to each other for immunogenicity and safety profile, even in co-administration with anti-pneumococcal and anti-rotavirus vaccination [11,12,13,14,15]. Moreover, large effectiveness studies have been performed in several European countries (including Sweden, Denmark, and Germany) concerning diseases such as pertussis and invasive Hib [16,17,18]. The safety data collected in the clinical studies on hexavalent vaccines have also demonstrated good tolerability of these vaccines, confirmed by phase IV post-marketing surveillance studies, reporting a higher percentage, but not statistically significant, of fever and mild, transitory, local symptoms compared to vaccines with fewer components [11,12,13, 19, 20]. It was estimated that in 2018 approximately 500,000 preterm infants have been vaccinated with Hexyon®, while a similar number of preterm infants in the same year were vaccinated with Infanrix Hexa® and Vaxelis® [8]. A recent publication by a panel of Italian experts from the Italian Society of Hygiene and Preventive Medicine, The Italian Society of Pediatrics and the Italian Federation of Pediatrics confirmed that all the three hexavalent vaccines can be used in preterm infants (Tables 1 and 2), [7]. The panel underlined that no delay in undertaking the national vaccination schedule can be justified in preterm infants, as well as reluctance in the co-administration of other vaccines, including anti-pneumococcal vaccine and anti-rotavirus vaccines. Once the absolute contraindications are excluded, vaccination should be executed basing on the chronological age of the child [6, 21,22,23,24]. This is particularly important considering that high prevalence of sepsis [25,26,27,28], pertussis [29], and other diseases [30, 31] have been reported in preterm infants.

Despite the national and international recommendations, however, several studies have shown low vaccination rates and delays in the majority preterm infants [32,33,34,35]. A post-marketing surveillance study on vaccination with Infanrix Hexa® and Hexyon® vaccines found that only 57.6% of preterm infants of the Puglia in 2017 had been vaccinated by their 90th day of life [36]. The ACTION follow-up project (Access to Intensive Care and Neonatal Obstetrics, Access to Obstetrical and Neonatological Intensive Care follow-up project) evaluated preterm infants at 22–31 weeks of EG in 5 Italian regions in 2003–2005 (Friuli-Venezia-Giulia, Tuscany, Marche, Lazio, Calabria) and showed that the delay in starting vaccination was correlated to a lower weight and EG at birth, to a second hospitalization after discharge from the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), to maternal / paternal unemployment, the number of children within the family, lower socio-economic status, positive anamnesis for cerebral palsy and ethnicity other than Caucasian [33]. Some possible reasons of the vaccination delay in preterm infants concern safety and efficacy of hexavalent vaccines in these children [37,38,39,40]. Hereby, we reviewed and summarized the recent literature regarding safety, efficacy and effectiveness of hexavalent vaccines in preterm infants, which further support the national and international recommendations.

Methods

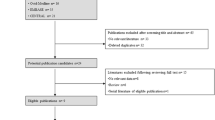

A systematic search of the literature published from 1 January 2008 to 30 June 2019 was performed on PubMed MEDLINE and Cochrane Library databases, using the following Boolean expression (“infant, preterm” [MeSH Terms]) AND “vaccination” [MeSH terms] AND “hevavalent vaccines” [MeSH terms]) and selecting only articles published in English. The reference of articles retrieved by this search strategy were also examined in order to recover any further relevant publications. A first screening of the selected articles was carried out on the basis of the title and the abstract. We included all prospective or retrospective observational studies and clinical trials regarding efficacy, effectiveness or safety profile of hexavalent vaccines in preterm infants. Studies that carried out a comparison between the hexavalent vaccination in full-term and preterm infants and studies in which hexavalent vaccines was co-administered with other vaccination types (e.g. anti-pneumococcal, anti-rotavirus, anti-VRS, anti-influenza) were included. The non-pertinent articles, commentaries, letters, case series concerning < 10 children cases, reviews, duplicates and articles not written in English were excluded. For each study the following data were evaluated and summarized in the tables: year of publication, study design, gestationale age (GA) of the population, number of study included, type of vaccination administered, outcomes (e.g. laboratory parameters for immunogenicity, clinical indicators for efficacy and reported adverse events for safety), follow-up period and any study bias / limits.

Results

Initially, 101 articles were retrieved by the search strategy. Sixteen articles regarding hexavalent vaccination in preterm infants have been identified, of which 13 and 5 concerned safety ([39, 40, 42]; Table 3) and efficacy/effectiveness (Table 4), respectively. In all these studies hexavalent vaccines were administered according to the primary 3-dose immunization schedule, as recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [43]. Among the 13 safety studies, 11 had hexavalent vaccination [39, 40, 42], as main objective, while 2 studies had, as their main objective, other types of vaccines (anti-pneumococcal and anti-rotavirus) in co-administration with hexavalent vaccines. In 9 out of 11 safety studies on hexavalent vaccines, other vaccines were co-administered [39, 40, 42] in the same vaccination session. Regarding the safety of hexavalent vaccines in preterm infants, several studies showed a similar or lower incidence of both local and systemic adverse events in preterm compared to full-term infants, probably due to the lower ability to induce an inflammatory response in preterm infants, even when co-administered with pneumococcal vaccine None of the serious adverse events observed in these studies were considered causally related to the vaccination. Apnoea and alterations in reactivity in preterm infants were the most frequently reported adverse events. Numerous studies have shown an increase in the incidence of apnoea episodes in preterm infants after hexavalent vaccination [40,41,42]. Preterm infants who have experienced apneoa episodes after hexavalent vaccination are generally those in more critical clinical conditions (e.g. previous late-onset sepsis), who required greater support through continous positive airway pressure, and who have a positive history for similar episodes, particularly in the 24 h prior to the administration of the vaccination [40,41,42]. A lower birth weight (< 2 kg), a lower GA (≤ 31 weeks) and chronological age (< 67 days), a positive history for similar episodes and hospitalization for complications related to prematurity are risk factors of recurrence of post-vaccination apnoea [40] also at the second dose of the vaccination schedule with variable percentage in the datasets (4.4–18%) [39, 40]. However, a causal relationship between the vaccine and the appearance of cardio-respiratory events continues to be, widely debated. The available studies are often retrospective, with no control group and with numbers of included children too limited to demonstrate a statistically significant difference in the incidence of these events in preterm infants. Furthermore, it is difficult to distinguish apnoea related to vaccination from those due to the clinical instability of preterm infants due to other associated comorbidities (e.g. periventricular hemorrhage, bronchopulmonary dysplasia or late onset sepsis). Indeed, the only available prospective randomized controlled trial by Carbone et al. suggests that the hexavalent vaccine administration is not associated with cardio-respiratory events, showing no difference in the frequency and severity of apnoea / bradycardia episodes in those who had received vaccination compared to controls. Given the potential risk of apnoea reported in several studies, however, preterm infants still hospitalized at 2 months of life should be vaccinated before discharge from the NICU with a clinical and respiratory monitoring for the 48–72 h following vaccination, particularly with regard to the very low birth weight (VLBW) preterm with a positive medical history for cardio-respiratory events, especially in the 24 h prior to the administration of the vaccine. If a cardio-respiratory episode has occurred after the first vaccine dose, the second dose should be administered in a protected environment in those individuals at high risk of recurrence.

Focusing on the immunogenicity of hexavalent vaccines, high seroprotection rates have been reported in preterm infants. However, a lower GA seems to be associated with lower antibody titres against some vaccine antigens (eg HBV, Hib, poliovirus serotype 1, and pertussis), regardless of the type of hexavalent vaccine used. These data are in agreement with previous studies in which the seroprotection rates reached 98.7–100% in preterm infants [43, 44]. Lower seroprotection rates, although still high, have been reported with respect to pertussis and Hib (92.4 and 92.5% respectively) [44]. Although lower GA and birth weight seem to be associated with lower antibody titres against Hib, a booster dose of hexavalent vaccine was able to induce a protective serological response (evaluated as anti-PRP [anti-polyribosyl ribitol phosphate] antibody concentration > 1 μg/mL) in 98.2% of preterm infants, suggesting an adequate immunological memory in this population [45]. On the other hand, the ability to induce an adequate humoral response to HBV in preterm infants is still debated. In large studies the seroprotection rates for HBV were similar in very low birth weight (VLBW) and low birth weight (LBW) (93.7% vs. 94.9% respectively), However, seroprotection rates were reinforced (> 98%) by booster vaccination for all antigens except for HBs in VLBW children: only 88.7% of those had anti-HBs antibody concentrations > or = 10 mIU/mL, compared with 96.5% of LBW children (the difference was not statistically significant) [43]. In contrast, Omenaca et al. did not observe no difference in the humoral response to HBV vaccination in preterm infants of lower GA and birth weight neither after primary cycle nor after a booster dose [46]. Only one study investigated the T cell-mediated response in preterm infants, showing comparable levels of memory T lymphocyte response for poliovirus antigens in full-term and preterm infants after hexavalent vaccination, but the latter demonstrate several nonspecific and poliovirus-specific functional T cell limitations. Moreover, although all infants developed seroprotective poliovirus antibody titers, serotype 1 titers were lower among preterm infants (P = 0.03).

The immunogenicity of the hexavalent vaccines in co-administration with other types of vaccines was evaluated in several studies [47]. Effectiveness studies regarding the use of hexavalent in preterm infants are very scarce at the moment. Furthermore, in the available studies, a 3 + 1 schedule was used characterized, as recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [48], while in some European countries, including Italy, a reduced (2 + 1) vaccination schedule is employed. Further studies are needed in order to define in greater detail the immunogenicity and effectiveness of hexavalent vaccines with reduced schedule in preterm infants, focusing also on the potential differences in the subgroup of severe preterm infants (< 29 weeks of EG), in order to assess the need for additional vaccine doses or for early administration of booster doses.

Conclusions

Hexavalent vaccines administered to preterm infants display a good safety and immunogenicity profile even when co-administrated with other vaccines included in the Italian schedule. Summarizing the results of the present review, it should be bared in mind that:. the three hexavalent vaccines available in Italy have the same indications and can be administered in preterm infants; • although further studies are needed regarding their effectiveness, no delay in vaccination of clinically stable preterm infants is justifiable; • preterm infants must be immunized according to their chronological age, in the same time and manner as those born at term; • severe preterm infants who are still hospitalized at the time when they should be vaccinated should receive the first dose during the hospitalization, particularly in the case of preterm infants ≤31 weeks, with a birth weight < 2.0 kg, with previous episodes of apnoea / bradycardia before vaccination and / or with severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia, in order to provide monitoring for cardiorespiratory events for the 48–72 h following vaccination; • if a cardio-respiratory episode has occurred after the first vaccination dose, the second dose should be administered in a protected environment; • the specific recommendation for the administration of hexavalent vaccines in the most severe preterm infants (≤ 28 weeks) or with a recent history of respiratory distress, as reported by EMA, includes an additional respiratory monitoring for 48 to 72 h after the vaccination.

Availability of data and materials

Please contact author for data requests.

References

Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco. Vaccinazioni come strumento di sanità pubblica: le conclusioni del Consiglio UE. Available at the website: www.aifa.gov.it/content/vaccinazioni-come-stru-mento-di-sanità-pubblica-le-conclusioni-del-consiglio-ue. Last accessed 23rd September, 2019.

Skibinski D, Baudner B, Singh MO, et al. Combination vaccines. J Global Infect Dis. 2011;3:63–72.

Decker MD. Principles of pediatric combination vaccines and practical issues related to use in clinical practice. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2001;20:10–8.

Maman K, Zollner Y, Greco D, et al. The value of childhood combination vaccines: from beliefs to evidence. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2015;11:2132–41.

Vidor E, Soubeyrand B. Manufacturing DTaP-based combination vaccines: industrial challenges around essential public health tools. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2016;15:1575–82.

Obando-Pacheco P, Rivero-Calle I, Gomez-Rial J, et al. New perspectives for hexavalent vaccines. Vaccine. 2018;36:5485–94.

Orsi A, Azzari C, Bozzola E, et al. Hexavalent vaccines: characteristics of available products and practical considerations from a panel of Italian experts. J Prev Med Hyg. 2018;59:E107–19.

White paper to understand the market structure of pediatric pertussis combination vaccines. Disponibile online al link: www.reportlinker.com/insight/white-paper-understand-market-structure-pediatric-pertussis-combination-vaccines.html.

Ministero della Salute. Piano Nazionale Prevenzione Vaccinale 2017–2019.

Pezzotti P, Bellino S, Prestinaci F, et al. The impact of immunization programs on 10 vaccine preventable diseases in Italy: 1900-2015. Vaccine. 2018;36:1435–43.

Infanrix Hexa®, RCP. Available at the website: https://farmaci.agenziafarmaco.gov.it/aifa/servlet/PdfDownloadServlet?pdfFileName=footer_000231_034960_RCP.pdf&retry=0&sys=m0b1l3. Last accessed 23rd September, 2019.

Hexyon®, RCP. Available at the website: https://farmaci.agenziafarmaco.gov.it/aifa/servlet/PdfDownloadServlet?pdfFileName=footer_000737_042817_FI.pdf&retry=0&sys=m0b1l3. Last accessed 23rd September, 2019.

Vaxelis®, RCP. Available at the website: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/vaxelisepar-product-information_it.pdf. Last accessed 23rd September, 2019.

Vesikari T, Silfverdal S, Jordanov E, et al. A randomized controlled study of DTaP-IPV-HB-PRP-T, a fully liquid hexavalent vaccine administered in a 3, 5 and 11 to 12 month schedule. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2017;36:87–93.

Silfverdal S, Icardi G, Vesikari T, et al. A phase III randomized double blind clinical trial of an investigational hexavalent vaccine given at 2,4 and 11-12 months. Vaccine. 2016;34:3810–6.

Hviid A, Stellfeld M, Andersen P, et al. Impact of routine vaccination with a pertussis toxoid vaccine in Denmark. Vaccine. 2004;22:3530–4.

Thiorry-Carstensen B, Dalby T, Stevner M, et al. Experience with monocomponent acellular pertussis combination vaccines for infants, children, adolescents and adults-a review of safety, immunogenicity, efficacy and effectiveness studies and 15 years of field experience. Vaccine. 2013;31:5178–91.

Kalies H, Grote V, Sielder A, et al. Effectiveness of hexavalent vaccines agains invasive Haemophilus influenzae type b disease. Germany’s experience after 5 years of licensure. Vaccine. 2008;26:2545–52.

Zepp F, Schmitt H, Cleerbout J, et al. Review of 8 years of ex perience with Infanrix Hexa TM (DTPa-HBV-IPV/Hib hexavalent vaccine). Expert Rev Vaccines. 2009;8:663–78.

AIFA. Rapporto sulla sorveglianza post marketing dei vaccini in Italia 2016. Available at the website: www.aifa.gov.it/sites/default/files/Rapporto_Vaccini_2016.pdf. Last accessed 23rd September, 2019.

Greenberg D, Feldman S. Vaccine interchangeability. Clin Pediatr. 2003;42:93–9.

Esposito S, Fumagalli M, Principi N. Immunogenicity, safety and tolerability of vaccinations in premature infants. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2012;11:1199–209.

Crawford NW, Bines JE, Royle J, et al. Optimizing immunization in pediatric special risk groups. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2011;10:175–86.

Palmeira P, Quinello C, Silveira-Lessa AL, et al. IgG placental transfer in healthy and pathological pregnancies. Clin Dev Immunol. 2012;2012:985646.

Siegrist CA, Córdova M, Brandt C, et al. Determinants of infant responses to vaccines in presence of maternal antibodies. Vaccine. 1998;16:1409–14.

Bonhoeffer J, Siegrist CA, Heath PT. Immunisation of premature infants. Arch Dis Child. 2006;91:929–35.

Lawn JE, Osrin D, Adler A, et al. Four million neonatal deaths: counting and attribution of cause of death. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2008;22:410–6.

Stoll BJ, Hansen N, Fanaroff AA, et al. Late-onset sepsis in very low birth weight neonates: the experience of the NICHD neonatal research network. Pediatrics. 2002;110:285–91.

Langkamp DL, Davis JP. Increased risk of reported pertussis and hospitalization associated with pertussis in low birth weight children. J Pediatr. 1996;128:654–9.

Shinefield H, Black S, Ray P, et al. Efficacy, immunogenicity and safety of heptavalent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in low birth weight and preterm infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2002;21:182–6.

Grohskopf LA, Sokolow LZ, Broder KR, et al. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices-United States, 2018-19 influenza season. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2018;67:1–20.

Sisson H, Gardiner E, Watson R. Vaccination timeliness in preterm infants: an integrative review of the literature. J Clin Nurs. 2017;26:4094–104.

Tozzi AE, Piga S, Corchia C, et al. Timeliness of routine immunization in a population-based Italian cohort of very preterm infants: results of the ACTION follow-up project. Vaccine. 2014;32:793–9.

Gopal SH, Edwards KM, Creech B, et al. Variability in immuniza tion practices for preterm infants. Am J Perinatol. 2018;35:1394–8.

Laforgia N, Di Mauro A, Bianchi FP, et al. Are pre-terms born timely and right immunized? Results of an Italian cohort study. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018;14:1398–402.

Moffa L, Fortunato F, Del Matto G, et al. Risultati preliminari di uno studio di sorveglianza postmarketing dei vaccini esavalenti nei bambini nati pretermine in Puglia nel 2017. 51° Congresso Nazionale SITI 2018 (abstract code: SIT9123–47). Available at the website http://www.igienistionline.it/docs/2018/41abstract.pdf. Last accessed 23rd September, 2019.

Moss SJ, Fenton AC, Toomey JA, et al. Responses to a conjugate pneumococcal vaccine in preterm infants immunized at 2, 3, and 4 months of age. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2010;17:1810–6.

Vázquez L, Garcia F, Rüttimann R, et al. Immunogenicity and reactogenicity of DTPa-HBV-IPV/Hib vaccine as primary and booster vaccination in low-birth-weight premature infants. Acta Paediatr. 2008;97:1243–9.

Clifford V, Crawford NW, Royle J, et al. Recurrent apnoea post immunisation: informing re-immunisation policy. Vaccine. 2011;29:5681–7.

Flatz-Jequier A, Posfay-Barbe KM, Pfister RE, et al. Recurrence of cardiorespiratory events following repeat DTaP-based combined immunization in very low birth weight premature infants. J Pediatr. 2008;153:429–31.

Chiappini E, Petrolini C, Sandini E, et al. Update on vaccination of preterm infants: a systematic review about safety and efficacy/effectiveness. Proposal for a position statement by Italian Society of Pediatric Allergology and Immunology jointly with the Italian Society of Neonatology. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2019;18:523–45.

Carbone T, McEntire B, Kissin D, et al. Absence of an increase in cardiorespiratory events after diphtheria-tetanus-acellular pertussis immunization in preterm infants: a randomized, multicenter study. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e1085–90.

Saari TN. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on infectious diseases. Immunization of preterm and low birth weight infants. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on infectious diseases. Pediatrics. 2003;112:193–8.

Omenaca F, Sarlangue J, Szenborn L, et al. Safety, reactogenici ty and immunogenicity of the human rotavirus vaccine in preterm European infants: a randomized phase IIIb study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012;31:487–93.

Klein NP, Gans HA, Sung P, et al. Preterm infants’ T cell responses to inactivated poliovirus vaccine. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:214–22.

McCrossan P, McCafferty C, Murphy C, et al. Retrospective review of administration of childhood primary vaccination schedule in an Irish tertiary neonatal intensive care unit. Public Health. 2015;30:1–3.

Omeñaca F, Merino JM, Tejedor JC, et al. Immunization of pre term infants with 10-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. Pediatrics. 2011;128:e290–8.

Wilińska M, Warakomska M, Głuszczak-Idziakowska E, et al. Risk factors for adverse events after vaccinations performed during the initial hospitalization of infants born prematurely. Dev Period Med. 2016;20:296–305.

Anderson J, Noori K, Morris SA. Apnoea after the 2-month immunisation in extremely preterm infants: what happens with the 4-month immunisation? J Paediatr Child Health. 2013;49:E217–20.

Furck AK, Richter JW, Kattner E. Very low birth weight infants have only few adverse events after timely immunization. J Peri natol. 2010;30:118–21.

DeMeo SD, Raman SR, Hornik CP, et al. Adverse events after routine immunization of extremely low birth weight infants. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169:740–5.

Hacking DF, Davis PG, Wong E, et al. Frequency of respiratory deterioration after immunisation in preterm infants. J Paediatr Child Health. 2010;46:742–8.

Klein NP, Massolo ML, Greene J, et al. Risk factors for developing apnea after immunization in the neonatal intensive care Unit. Pediatrics. 2008;121:463–9.

Vermeulen F, Dirix V, Verscheure V, et al. Persistence at one year of age of antigen-induced cellular immune responses in preterm infants vaccinated against whooping cough: comparison of three different vaccines and effect of a booster dose. Vaccine. 2013;31:1981–6.

Omeñaca F, Arístegui J, Tejedor JC, et al. Combined Haemophi lus Influenzae type B-Neisseria meningitidis serogroup C vaccine is immunogenic and well tolerated in preterm infants when coadministered with other routinely recommended vaccines. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30:e216–24.

Omeñaca F, Garcia-Sicilia J, Boceta R, et al. Hepatitis B re sponse of premature infants after primary and booster immunisation with a diphtheria-tetanus-acellular pertussis-hepatitis B-inactivated poliovirus/haemophilus influenzae type B vaccine. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2010;2010:802503.

Omeñaca F, Garcia-Sicilia J, García-Corbeira P, et al. Response of preterm newborns to immunization with a hexavalent diphtheria-tetanus-acellular pertussis-hepatitis B virus-inactivated polio and Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccine: first experiences and solutions to a serious and sensitive issue. Pediatrics. 2005;116:1292–8.

Omeñaca F, Garcia-Sicilia J, Boceta R, et al. Antibody persistence and booster vaccination during the second and fifth years of life in a cohort of children who were born prematurely. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007;26:824–9.

Omeñaca F, Garcia-Sicilia J, García-Corbeira P, et al. Antipolyri bosyl ribitol phosphate response of premature infants to primary and booster vaccination with a combined diphtheria-tetanus-acellular pertussis-hepatitis B-inactivated polio virus/Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccine. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e179–85.

Omeñaca F, Garcia-Sicilia J, Boceta R, et al. Hepatitis B response of premature infants after primary and booster immunisation with a diphtheria-tetanus-acellular pertussis-hepatitis B-inactivated poliovirus/haemophilus influenzae type B vaccine. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2010;2010:802503.

Omeñaca F, Vázquez L, Garcia-Corbeira P, et al. Immunization of preterm infants with GSK’s hexavalent combined diph-theria-tetanus-acellular pertussis-hepatitis B-inactivated poliovirus-Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccine: a review of safety and immunogenicity. Vaccine. 2018;36:986–96.

Robinson CL, Bernstein H, Romero JR, et al. Advisory committee on immunization practices recommended immunization schedule for children and adolescents aged 18 years or younger United States, 2019. Weekly. 2019;68:112–4.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest with respect to the topics discussed in the article.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Contributions to conception, CE, PC, CC; design of the work: MF, MGL; acquisition, analysis: CE, PC, CC; have drafted the work and revised it: CM.4, CF 5, DM 6, LA 7, MS 8, MA 9, MD 10, MDGM 11, PGB 12, PC 13, PL 13, TMA. All the authors have approved the submitted version and have agreed both to be personally accountable for the author’s own contributions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Chiappini, E., Petrolini, C., Caffarelli, C. et al. Hexavalent vaccines in preterm infants: an update by Italian Society of Pediatric Allergy and Immunology jointly with the Italian Society of Neonatology. Ital J Pediatr 45, 145 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13052-019-0742-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13052-019-0742-7