Abstract

Background

Previous reports suggest a benefit associated with haploidentical donor transplantation (HIDT) compared to matched sibling donor transplantation (MSDT) in certain contexts, and the choice of optimal candidates warrants further investigation.

Methods

We designed a prospective genetically randomized study to evaluate donor options between acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) patients positive for measurable residual disease (MRD) pre-transplantation who underwent HIDT (n = 169) or MSDT (n = 39).

Results

The cumulative incidence of positive MRD post-transplantation was 26% (95% CI, 19–33%) and 44% (95% CI, 28–60%) for HIDT and MSDT, respectively (P = 0.043). Compared to the HIDT cohort, the MSDT cohort had a higher 3-year cumulative incidence of relapse (CIR; 47%, 95% CI, 31–63% vs. 23%, 95% CI, 17–29%; P = 0.006) and lower 3-year probability of leukemia-free survival (LFS; 43%, 95% CI, 27–59% vs. 65%, 95% CI, 58–72%; P = 0.023) and overall survival (OS; 46%, 95% CI, 30–62% vs. 68%, 95% CI, 61–75%; P = 0.039), without a difference in non-relapse-mortality (10%, 95% CI, 1–19% vs. 11%, 95% CI, 6–16%; P = 0.845). Multivariate analysis showed that HIDT is associated with a low CIR (HR = 0.364; 95% CI, 0.202–0.655; P = 0.001) and better LFS (HR = 0.414; 95% CI, 0.246–0.695; P = 0.001) and OS (HR = 0.380; 95% CI, 0.220–0.656; P = 0.001).

Conclusions

HIDT is better than MSDT in view of favorable anti-leukemia activity for patients with pre-transplantation MRD positive ALL. The current study paves the way to determine that haploidentical donors are the preferred choice regardless of available matched sibling donors in a subgroup population.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02185261. Registered July 9, 2014. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02185261?term=NCT02185261&draw=2&rank=1.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Currently, haploidentical donors have been an alternative source for allo-stem cell transplantation (SCT) for patients that require transplantation but have no related or unrelated donors with matching human leukocyte antigen (HLA) [1,2,3,4,5]. With the increasingly used haploidentical SCT (HIDT), HLA-identical sibling donors remain the first choice, though a number of studies have shown that treating patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) using haploidentical donors (HIDs) could achieve comparable outcomes to those who undergoing HLA-matched sibling donor transplantation (MSDT) [3, 6, 7]. On the other hand, using haploidentical transplants, the graft-versus-leukemia (GVL) effect may be stronger, as mismatches for HLA antigens on leukemic cells would provide allo-immune targets [4, 5, 8,9,10,11,12,13]. A recent large European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) study indicated that HIDT has a lower incidence of relapse than MSDT for low-risk (HR = 0.83, P = 0.011) and intermediate-risk (HR = 0.85, P = 0.033) hematological malignancies [5]. The better relapse rate with HIDT compared to MSDT has also been observed in patients with lymphomas [8, 9]. Our previous studies showed that HIDT is superior to MSDT in terms of a lower relapse rate for patients with high-risk leukemia [11]. Furthermore, for older patients with acute leukemia, offspring donors not only result in lower non-relapse mortality (NRM), but also tended to be associated with a lower risk of relapse than MSDT [12]. Although these reports have effectively proven the potential superiority of HIDT to MSDT in the context of relapse risk in treating patients with some specified subgroups of hematological malignancies [4, 5, 8,9,10,11,12], they cannot inform decision-making in choosing one donor type over another for a specific patient due to the retrospective nature of the studies or highly diverse populations and various transplant regimens [4, 5, 8,9,10,11,12,13].

Apart from heterogeneous disease type, the variations in comparative outcomes between HIDT and MSDT could also be related to differences in disease status at the time of allo-SCT (i.e., less advanced disease or minimal residual disease [MRD]) [2, 4, 6, 13,14,15,16,17]. Therefore, studies have been performed in more homogenous groups [10]. Our group recently reported that, for AML patients with pre-transplantation MDR positivity (pre-HSCT MRDpos), HIDT could achieve a significantly lower cumulative incidence of relapse (CIR) and better survival than those who underwent MSDT [10]. Although this study included a prospective cohort with an homogenous population, there are some limitations with this prospective subgroup [10]. First, the sample size for pre-HSCT MRDpos (n = 76) was not large enough to reach reliable statistic power. Second, although the percentages of preemptive donor lymphocyte infusion (DLI) for post-HSCT MRD were described, there was neither a direct comparison of the incidence of post-transplantation MRD positivity (post-HSCT MRDpos) between donor sources nor a comparison of the proportion of interventions for post-HSCT MRDpos [10]. Considering these limitations [10], prospective comparative studies with enough power and more solid evidence of HIDT being better at eradiating leukemia cells are needed to challenge the traditional donor hierarchy of matching sibling donors (MSDs) being the first choice [14, 15].

For patients with ALL, a more recent EBMT study revealed that HIDT can obscure the negative effects of pre-HSCT MRDpos before transplantation in a subgroup analysis (CIR, 29% vs. 26% and leukemia-free survival, LFS, 50% vs. 50% for pre-HSCT MRDpos and pre-HSCT MRDneg, respectively) [16]. Though all of these findings [5, 8,9,10,11, 13] suggested a benefit associated with HIDT in certain contexts, the choice of an optimal candidate in terms of a stronger GVL effect warrants further investigation. Therefore, we designed a prospective genetically randomized study to evaluate donor options by comparing the endpoints related to disease control between ALL patients with pre-HSCT MRDpos who underwent HIDT and those who received MSDT. In this study with an homogenous population and unified transplant regimen, we provide convincing evidence that HIDT is favorable over MSDT in certain groups of patients, possibly by exerting a stronger GVL effect. Our results demonstrate that HIDT is associated with a lower incidence of post-HSCT MRDpos, lower CIR, and superior survival compared to MSDT. Our findings could have a major impact on donor selection regardless of available MSDs [14, 15].

Methods

Study design and patients

This was a prospective cohort sub-study of a parent trial performed at Peking University Institute of Hematology (NCT02185261). Patients were assigned to groups transplanted with HIDT or MSDT based on donor availability (genetical randomization). Enrollment began in July 2014 and ended in February 2018. MSDT (6/6 matching HLA-A, B, and DR loci) was the first choice for allo-HSCT [14, 15]. If an HLA-matched sibling donor was unavailable, subjects without a suitable closely HLA-matched unrelated donor (> 8 of 10 matching HLA-A, B, C, DR, and DQ loci and > 5 of 6 matching HLA-A, B, and DR loci) after two cycles of consolidation were eligible for HLA-haplotype transplantation. For this comparative analysis to arrive at comparable patient cohorts that received transplants during the same time period, we excluded patients who underwent unrelated donor (URD) SCT (n = 20, Fig. 1). Patients who met the following criteria were included: age 3–65 years and ALL in complete remission (CR) with pre-HSCT MRDpos. Exclusion criteria were severe heart, kidney, or liver disease, a prior transplant, and hypersensitivity to rabbit anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG) if a haploidentical donor was available. The diagnosis of ALL was based on the NCCN criteria [17].

CONSORT (the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) diagram. Abbreviations: ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; CR, complete remission; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; MRD, measurable residual disease; MSDT, human leukocyte antigen-matched sibling donor transplantation; Haplo-SCT, haploidentical stem cell transplantation

The MRD status was assessed in all patients in morphologic CR at transplant using validated methods (multiparametric flow cytometry for all patients, reverse transcriptase quantitative polymerase chain reaction for Philadelphia chromosome (PH) positive ALL, see below “detection of MRD”). As mentioned above, patients generally receive allo-HSCT after two cycles of consolidation and within 2 weeks after MRD assessment. Routine MRD monitoring was performed at 1, 2, 3, 4.5, 6, 9, and 12 months post-transplantation and at 6-month intervals thereafter. This study was performed in accordance with the modified Helsinki Declaration, and the protocol was approved by our ethical review boards before study initiation. Informed consent was obtained from all donors and recipients.

Donors

Donor selection and HLA typing were performed as described previously [2, 3, 6, 18]. Donor-recipient pair was identified as HLA-identical or haploidentical matched according to the familial spectrum of genetics analysis.

Chemotherapy prior to Allo-SCT

For the induction of CR, the patients received chemotherapy in accordance with the national ALL protocols, which included vincristine, daunorubicin, cyclophosphamide (Cy), l-asparaginase, and prednisone (VDCLP); vincristine, daunorubicin, cyclophosphamide, and prednisone (VDCP); vincristine, daunorubicin, l-asparaginase, and prednisone (VDLP); or vincristine, daunorubicin, and prednisone (VDP). Consolidation chemotherapy regimens included Cy, doxorubicin, vincristine, and dexamethasone (Hyper-CVAD [A]); methotrexate (MTX) and cytosine arabinoside (Ara-c) (Hyper-CVAD [B]); MTX and l-asparaginase; or Cy, Ara-c, and mercaptopurine (CAM), which were given in turn. Patients who did not achieve CR after induction received re-induction chemotherapy, which included VDCP; VDCLP; Ara-C, mitoxantrone, and etoposide (MAE); MTX and l-asparaginase; or Hyper-CVAD (B). Patients received re-induction chemotherapy according to doctor experience and patient intention. Prophylaxis for central nervous system leukemia consisted of intrathecal chemotherapy with at least six doses of MTX, Ara-c, and dexamethasone during induction chemotherapy and consolidation chemotherapy. The two study groups did not differ in the inductions they received (P = 0.52).

Transplant protocol

Patients were treated with a myeloablative conditioning regimen according to a previous study by our group [3]. The conditioning therapies for the HID group were as follows: cytarabine (4 g/m2/d) intravenously on days –10 to –9; busulfan (3.2 mg/kg/d) intravenously on days –8 to –6; cyclophosphamide (1.8 g/m2/d), intravenously on days –5 to –4; Me-CCNU (250 mg/m2/d), orally once on day –3; and ATG (thymoglobulin, 2.5 mg/kg/d, Sang Stat, Lyon, France) intravenously on days –5 to –2. Patients in the MSD cohort received hydroxycarbamide (80 mg/kg) orally on day –10 and a lower dose of cytarabine (2 g/m2/d) on day –9, but otherwise, an identical regimen to the HID patients without ATG was employed. Acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) prevention and treatment were performed according to our previous study [3, 6, 19]. On the basis of bone marrow allogeneic graft CD4:CD8 ratios, patients in the HIDT cohort were categorized as low GVHD risk or high GVHD risk [19]. Patients at high GVHD risk in the HIDT cohort received low-dose corticosteroid prophylaxis [19]. In addition, two doses of 14.5 mg/kg Cy was given on days 3 and 4 after HSCT from maternal donors during the trial period [20].

Cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr virus monitoring and prevention

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) levels were monitored and infections treated as described previously [3, 6, 19].

Detection of MRD by multiparameter flow cytometry

Eight-color multiparameter flow cytometry (MFC) was performed in all patients as a routine clinical test with the sensitivity of 10−5 on bone marrow aspirate samples that were obtained as part of the baseline assessment before SCT, as well as 1, 2, 3, 4.5, 6, 9, and 12 months post-transplantation and at 6-month intervals thereafter.

A panel of eight antibody combinations that recognize cCD3, mCD3, CD2, CD5, CD7, CD10, CD19, CD20, CD34, CD38, CD45, CD58, CD99, CD123, and cTDT was used for MRD detection, and 0.2–1 million events per tube were acquired on a FACS Cant II. Isotype control monoclonal antibodies were used. MRD positivity was considered when a cluster of more than 20 cells with leukemia-associated immunophenotypes (LAIPs) and side scatter characteristics, identified in all plots of interest and carrying at least two LAIP markers identified at diagnosis, were observed. For those without LAIP markers at diagnosis, MRD was identified as a cell population deviating from the normal patterns of antigen expression seen on specific cell lineages at specific stages of maturation compared to either normal or regenerating marrow [21]. A lower limit of detection of 0.001% was targeted. When abnormal cells were identified, the cells were quantified as a percentage of the total CD45 positive white cell events. Any level of MRD was considered positive. The standardized assays and quality controls were performed according to previous reports [21]. The results of the MFC assessments of MRD were made available to the transplant teams. The two study groups did not differ in the proportion of patients with pre-HSCT MRDpos (29% vs. 27%, P = 0.73, Fig. 1).

Interventions for MRD after transplantation

To prevent relapse, interferon-α (IFNα) was used as described in our protocol [22]. During the study period (from July 2014), PH-negative ALL patients who were MRD-positive 60 days post-transplantation was planned to receive subcutaneous IFNα-2b (3 million units) 2–3 times per week. IFNα-2b was continued for 6 months in the absence of disease progression or unacceptable toxicity. Before July 2014, most patients received preemptive G-CSF-mobilized DLI for post-HSCT MRDpos and our previous study showed comparable efficacy for IFNα-2b or DLI [22]. Thus, according to patient preference, preemptive G-CSF-mobilized DLI was also allowed in patients with post-HSCT MRDpos when donor lymphocytes were available if patients had no active GVHD [23]. Short-term immunosuppressive agents were used to prevent GVHD after DLI. The details of preemptive DLI were published previously [23, 24]. Tyrosine kinase inhibitor was preemptively administered to patients with BCR/ABL [25, 26]. The two study groups did not differ in the proportion of IFN use for the post-HSCT MRDpos intervention (67% vs. 68%, Table 1). The treatment of GVHD following IFN or DLI included methylprednisolone, prednisone, and CsA, among others.

Definitions and evaluation

Engraftment, post-HSCT MRDpos, NRM, relapse, LFS, and overall survival (OS) were defined as described previously [3, 19]. Bacteremia was defined as the isolation of a bacterial pathogen from at least 1 blood culture. For coagulase-negative staphylococci and common skin contaminants, at least 2 sets of positive blood cultures were required. Invasive fungal infection (IFI) was evaluated according to the revised European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group (EORTC/MSG) 2008 criteria, with only proven and probable cases included. Acute GVHD was defined and graded based on the pattern and severity of organ involvement [19]. Chronic GVHD was defined and graded according to the National Institute of Health criteria [19]. Relapse was defined based on histological criteria [3, 19]. GVHD-free, relapse-free survival (GRFS) events were defined as grade III-IV aGVHD, chronic GVHD (cGVHD) requiring systemic immunosuppressive treatment, leukemia relapse, or death from any cause during follow-up after allo-HSCT.

End-points

The primary study end-point was LFS. Secondary end-points were the engraftment rate, the incidence of acute GVHD grades II–IV and chronic GVHD, and the cumulative incidence of MRD after transplantation, relapse, NRM, OS, and GRFS. To determine whether there was any difference in LFS between MSDT and HIDT, the cumulative incidence approach was used with a one-sided confidence interval (CI) for the difference in the Kaplan-Meier estimate of the 3-year LFS. With a planned sample size of 39 MSDT patients and 169 HIDT patients, 80% power can be achieved against the hypothesis of a 20% absolute increase in LFS after HIDT (60%) from 35% of patients with pre-HSCT MRDpos leukemia free survived after MSDT at a significance level of P = 0.05 in the Student one-tailed t test [21, 27].

Statistical analysis

The two groups were compared by the χ2 statistic for categorical variables and the Mann–Whitney test for continuous variables. Cumulative incidence curves were used in a competing risk setting, with relapse treated as a competing event to calculate NRM probabilities, and with death from any cause as a competing risk for GVHD, engraftment, post-HSCT MRDpos, and relapse. Time to GVHD was defined as the time from transplantation to the onset of GVHD of any grade. The probabilities of LFS and OS were estimated by the Kaplan–Meier method. All variables in Table 1 were included in the univariate analysis. Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to evaluate the relative risk of subjects undergoing transplantation by forcing the main interest variable (HID vs. MSD, using MSD as the reference group) into the model. The Fine and Gray model was used for analysis of endpoints involving competing risks. Backward elimination with a criterion of P < 0.10 for retention was used to select a final model. The following variables were analyzed: age at transplantation, diagnosis (PH positive B-ALL vs. PH negative B-ALL vs. T-ALL), disease status (CR2 vs. CR1), time from diagnosis to HSCT, donor-recipient sex match (female-male vs. others), donor source (MSD vs. HID), pre-HSCTMRD level, post-HSCTMRD status (neg vs. pos), and acute and chronic GVHD. Unless otherwise specified, P values were based on two-sided tests. Alpha was set to 0.05. Most analyses were performed in SPSS 16.0 (Mathsoft, Seattle, WA, USA).

Results

Study population

A total of 745 ALL patients who achieved CR after chemotherapy were enrolled in this study (Fig. 1). Twenty of these patients were excluded due to receiving matched unrelated donor transplantation, and 517 patients were excluded due to achieving CR with pre-HSCT MRDneg. Finally, 208 cases with pre-HSCT MRDpos were genetically randomized into the HIDT (n = 169) and MSDT groups (n = 39).

Patients, disease, and donor characteristics are summarized in Table 1. One-hundred twenty patients were Ph− B-ALL (58%), 59Ph+ B-ALL (28%), and 29 (14%) were T-ALL. Recipients of HIDT and MSDT were comparable concerning gender, time from diagnosis to HSCT, disease subtype and status, and pre-HSCT MRD level (Table 1). However, patients in the MSDT group were older than those in the HIDT group; also, as mentioned above, each HIDT patient received ATG while MSDT patient did not, and low-dose corticosteroid prophylaxis was given to 89 patients in the HIDT cohort.

Engraftment, GVHD, and infection

All patients achieved sustained, full donor chimerism. The 100-day cumulative incidence of platelet engraftment in the HIDT group was significantly lower than that in the MSDT group (95%, 95% CI, 92–98% vs. 100%, P < 0.001, Table 2). Multivariate analysis (MVA) showed that CD34 cell infused was the only significant factor associated with both neutrophil and platelet engraftment (Table 3).

The cumulative, 100-day incidence of acute GVHD grades II–IV and grades III–IV in the HIDT group was similar to that of the MSDT group (21%, 95% CI, 17–27% vs. 23%, 95% CI, 10–36%; P = 0.884; and 6%, 95% CI, 3–9% vs. 5%, 95% CI, 0–12%; P = 0.838). In addition, the 3-year cumulative incidence of total chronic GVHD and moderate to severe chronic GVHD was comparable between the HIDT and MSDT groups (44%, 95% CI, 36–52% vs. 48%, 95% CI, 31–65%; P = 0.850; and 18%, 95% CI, 10–26% vs. 27%, 95% CI, 10–44%; P = 0.192). MVA indicated that disease status was correlated with acute GVHD while time from diagnosis to HSCT affecting chronic GVHD (Table 3).

The 100-day cumulative incidence of CMV or EBV reactivation after engraftment in the HIDT group was significantly higher than that in the MSDT group (68%, 95% CI, 61–75% vs. 18%, 95% CI, 6–30%; P < 0.001; 15%, 95% CI, 10–21% vs. 0; P = 0.011; Table 2). The 100-day cumulative incidence of bacteremia or IFI after engraftment in the HIDT group was comparable to that in the MSDT group (4%, 95% CI, 1–7% vs. 3%, 95% CI, 0–8%; P = 0.784; 8%, 95% CI, 4–12% vs. 3%, 95% CI, 0–8%; P = 0.342).

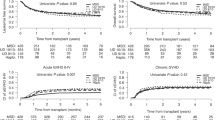

Non-relapse mortality and causes of death

The 3-year cumulative incidence of NRM was comparable between the HIDT and MSDT groups (11%, 95% CI, 6–16% vs. 10%, 95% CI, 1–19%; P = 0.845; Table 2 and Fig. 2c). MVA demonstrated that platelet engraftment and acute GVHD affected NRM (Table 3). Causes of death are shown in Table 4. Infection was the major cause of NRM.

Outcome of allogeneic stem cell transplantations in two cohorts after a median follow-up of 820 days. a Cumulative incidence of positive measurable/minimal residual disease after transplantation (overall P value for uni- and multivariate analysis was 0.024 and 0.018). b Cumulative incidence of leukemia relapse (overall P value for uni- and multivariate analysis was 0.008 and 0.001). c Non-relapse mortality (overall P value for uni- and multivariate analysis was 0.869 and 0.478). d Leukemia-free survival (overall P value for uni- and multivariate analysis was 0.025 and 0.001). e Overall survival (overall P value for uni- and multivariate analysis was 0.042 and 0.001). Abbreviations: Haplo-SCT, haploidentical stem cell transplantation; MSDT, human leukocyte antigen-matched sibling donor transplantation; MRD, measurable residual disease

Post-HSCT MRDpos, interventions, and relapse

Until the last follow-up, 62 patients with post-HSCT MRDpos were observed, 45 in the HIDT group and 17 in the MSDT group. The cumulative incidence of post-HSCT MRDpos was 26% (95% CI, 19–33%) and 44% (95% CI, 28–60%; P = 0.043, Table 2 and Fig. 2a). MVA showed that an HID was a beneficial factor, while higher level of pre-HSCT MRDpos was a risk factor for post-HSCT MRDpos (Table 3).

Details of preemptive interventions for post-HSCT MRDpos are described in Table 1. Seven patients, including six in the HIDT group and one in the MSDT group, received no intervention because these cases relapsed within 2 weeks after the detection of MRD post-transplantation (n = 6) or had active GVHD (n = 1, Table 1). As mentioned above, we found no significant differences in the different preemptive methods between these two groups, with IFN being the most frequently used modality (P = 0.83, Table 1). After preemptive interventions, 21 patients (21/55, 38%) eventually experienced hematological relapse, including 12/39 HIDT cases (31%) and 9/16 MSDT cases (56%; P = 0.12). In the HIDT or MSDT cohort, 9 of 29 patients (31%) and 7 of 11 (64%) receiving IFNα (P = 0.08), 3 of 6 (50%) and 2 of 3 (66%) receiving preemptive DLI, and none of the 6 (0%) receiving tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) relapsed, respectively.

The 3-year cumulative incidence of post-HSCT MRD or hematological relapse, whichever occurred first, was 38% (95% CI, 31–45%) and 64% (95% CI, 50–78%) in the HIDT and MSDT groups, respectively (P = 0.006). Compared to those receiving HIDT, patients who underwent MSDT had a higher 3-year CIR (47%, 95% CI, 31–63% vs. 23%, 95% CI, 17–29%; P = 0.006; Table 2 and Fig. 2b). The therapies of relapse included chemotherapy followed by therapeutic DLI (n = 21), TKI followed by DLI (n = 4), chimeric antigen receptor T-cell immunotherapy (CART) cell infusion (n = 3), and the others received chemotherapy (n = 10) or TKI alone (n = 2) or no therapy (n = 16). MVA showed that an HID and occurrence of chronic GVHD were beneficial factors, while T-ALL, more than CR1, higher level of pre-HSCT MRDpos, and post-HSCT MRDpos were risk factors for relapse (Table 3).

LFS, OS, and GRFS

Compared to those receiving HIDT, patients who underwent MSDT had a lower 3-year LFS (43%, 95% CI, 27–59% vs. 65%, 95% CI, 58–72%; P = 0.023; Fig. 2d) and OS (46%, 95% CI, 30–62% vs. 68%, 95% CI, 61–75%; P = 0.039; Fig. 2e) and a trend of lower GRFS (36%, 95% CI, 21–51% vs. 54%, 95% CI, 46–52%; P = 0.055; Table 2). MVA showed that an HID, platelet engraftment, and occurrence of chronic GVHD were beneficial factors, while T-ALL, more than CR1, higher level of pre-HSCT MRDpos, occurrence of acute GVHD, and post-HSCT MRDpos were risk factors for LFS and OS (Table 3).

Subgroup analysis for patients with sensitivity at 0.01% in the bone marrow for pre-HSCT MRDpos

With the aim that the study results can be compared with literature, we did analysis for patients with sensitivity at 0.01% in the bone marrow for pre-HSCT MRDpos (n = 128) including 24 MSDT and 104 HIDT. The 3-year CIR, LFS, and OS was 46% (95% CI, 24–68%) vs. 29% (95% CI, 20–38%; P = 0.159), 37% (95% CI, 17–57%) vs. 55% (95% CI, 45–65%; P = 0.175) and 43% (95% CI, 23–63%) vs. 59% (95% CI, 49–69%; P = 0.270) for patients who underwent MSDT or HIDT, respectively, whereas NRM rate was similar (17%, 95% CI, 0–34% vs. 15%, 95% CI, 8–22%; P = 0.782).

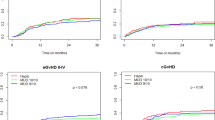

Outcomes for patients with pre-HSCT MRDneg

During the study period, patients with pre-HSCT MRDneg (n = 517) were also randomized genetically to choose MSD (n = 92) or HID (n = 425, Fig. 1). Patients, disease, and donor characteristics are summarized in Table S1. Compared to those receiving HIDT, patients who underwent MSDT had comparable 3-year CIR (16%, 95% CI, 8–24% vs. 15%, 95% CI, 11–19%; P = 0.776), LFS (72%, 95% CI, 63–81% vs. 68%, 95% CI, 64–72%; P = 0.463), OS (73%, 95% CI, 64–82% vs. 70%, 95% CI, 66–74%; P = 0.528), and NRM (12%, 95% CI, 5–19% vs. 16%, 95% CI, 12–20%; P = 0.274, Table S2 and Figure S1).

Outcomes for PH+ ALL patients

During the study period, PH+ ALL patients (n = 194) were also randomized genetically to choose. There are 124 Ph+ ALL cases with pre-HSCT MRDpos determined by real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) in the 725 ALL patients. In this subgroup, we found that the CIR between HIDT (n = 48) and MSDT (n = 18) was 18% (95% CI, 10–37%) and 12% (95% CI, 5–19%), respectively (P = 0.450). The NRM, LFS, and OS between these HIDT and MSDT groups were also comparable (data not shown). There are fifty-five Ph+ ALL cases with pre-HSCT MRDpos determined by RT-PCR in the 208 patients with pre-HSCT MRDpos detected by 8-color MFC. In this subgroup, we found that the CIR between HIDT (n = 48) and MSDT (n = 7) was 17% (95% CI, 6–28%) and 43% (95% CI, 5–80%), respectively (P = 0.106). The NRM, LFS, and OS between these HIDT and MSDT groups were also comparable (data not shown).

Discussion

The criteria for selecting the most appropriate transplant donor remain a topic of ongoing debate [4, 5, 8, 9, 11, 12, 14, 15]. This prospective, genetically randomized study provided the most robust evidence thus far that HIDT is superior to MSDT, potentially due to stronger GVL effects in certain patients. As opposed to most retrospective comparative studies between HIDT and MSDT, or a few prospective cohorts with limited statistical power [5, 8,9,10,11, 13]. The strengths of this analysis include a relatively large number of homogenous patients using consistent supportive care algorithms, conditioning regimens, and stem cell sources. Such genetically randomized studies are one means of providing guidance regarding a change in the traditional donor hierarchy of MSD being first choice in certain circumstances [14, 15].

In theory, choosing a donor with greater HLA disparity from the recipient could mitigate the relapse risk induced by a greater allo-immune GVL effect [5, 16, 28]. However, apart from donor type, many factors can influence GVL [2, 22, 23, 25], including disease type and remission status before HSCT, patient age, conditioning regimen, GVHD prophylaxis, number of T cells infused, presence of GVHD, use of immunotherapy and targeted drugs, and other factors. Because of the profound effect of MRD on transplant outcomes [21, 27, 29], this situation was chosen for close examination in the scenario of evaluating donor selection. The current study demonstrated that, for ALL patients with pre-HSCT MRDpos, HIDT can achieve lower CIR and better survival than MSDT. Moreover, we observed that, compared to patients undergoing MSDT, patients who underwent HID had a lower incidence of post-HSCT MRDpos and a lower proportion required preemptive therapy. All patients in the two study groups were treated with similar conditioning regimens without in vitro T-cell depletion. The one disparity in the GVHD prophylaxis schedule was that all HIDT recipients received ATG, which was not used for MSDT recipients [3, 19]. The requirement for additional immunosuppression in the HIDT protocol is an integral aspect of the current standards of GVHD prophylaxis [6, 19]. Furthermore, the use of ATG to facilitate engraftment and prevent GVHD without influencing relapse may not weaken the GVL effect [30]. Also, low-dose corticosteroid prophylaxis given to high GVHD risk HIDT patients did not influence relapse (data not shown), which confirmed our previous results [19]. Another unbalanced feature between the two groups is patient age. Due to the one child policy in China, half of our HIDs were parents [2, 3, 6]; thus, an age difference existed between the two study groups (Table 1). Though younger patients are prone to biologically less aggressive leukemia [31], our study populations were all transplanted in CR with pre-HSCT MRDpos, and age was not a significant factor affecting CIR in the multivariate analysis. Therefore, the lower incidence of post-HSCT MRDpos and lower CIR in the HIDT group cannot be explained exclusively by any of the confounding factors discussed. Our data, together with other studies on AML or Hodgkin’s lymphoma [8, 9], offer the most compelling evidence that choosing a HID over MSD has a favorable anti-leukemia effect [32]. However, the biological and immunological mechanism of donor choice based on GVL needs to be explored further. Apart from donor source, disease type and status also affected CIR, with T-ALL being worse than B-ALL and more than CR1 being inferior to CR1 as expected.

As disease control can be improved with greater use of immunomodulatory or targeted approaches [22, 23], we described preemptive interventions for MRD post-transplantation. Among patients with post-HSCT MRDpos, both the proportion and methods of preemptive interventions were similar between the two groups, with IFN most frequently used, followed by DLI [22, 23]. HIDT tended to have a lower relapse rate than MSDT after preemptive intervention for MRD post-transplantation (31% vs. 56%, P = 0.12) or in subgroup analysis after IFN (31% vs. 64%, P = 0.08). These data confirmed the predictive role of MRD on prognosis [21, 29] and the effectiveness of preemptive therapies in both transplant modalities, but they also provide further evidence that HIDT offers an advantage over MSDT in terms of a better response to preemptive interventions for MRD post-transplantation [22, 23].

Weighing the likelihood of relapse versus GVHD and non-relapse mortality could guide donor selection [2, 4, 14, 15]. The similar rate of acute GVHD between the two groups was somewhat contradictory to our previous comparative studies with higher grades II–IV acute GVHD in HIDT than MSDT [3, 6]. Our risk stratification-directed, low-dose corticosteroid prophylaxis for GVHD in HIDT and lower proportion of female donors (29% vs. 41%) in the HIDT group may contribute to the comparable GVHD incidence between the two cohorts [2, 19]. Instead, disease status and time from diagnosis to HSCT affected acute or chronic GVHD. The equivalent NRM was in accordance with our previous reports of acute leukemia patients transplanted in CR [3, 10]. Thus, the HLA-antigen mismatch with HIDs contributes to greater allo-immunity against the tumor without affecting the allo-immunity against the host, partly due to advancements in GVHD prevention and infection control [2, 6, 19]. Thus, the tension between relapse and NRM translated to superior survival after HIDT [4]. Apart from donor source, T-ALL, more than CR1, acute GVHD had detrimental effect on survival while platelet engraftment and chronic GVHD had protective effect on survival. In addition, patients with pre-HSCT MRDneg had a higher LFS than those with pre-HSCT MRDpos in MSDT settings (P = 0.004), but LFS was comparable in HIDT settings for patients with pre-HSCT MRDneg versus pre-HSCT MRDpos (Figure S1), which indicated that, in accordance with our previous results of AML patients [10], HIDT could obscure the negative effect of pre-HSCT MRDpos in ALL patients while MSDT could not.

Regarding health-related quality of life (HRQoL), our previous retrospective study showed that the HRQoL of patients receiving HIDT is comparable to that of patients receiving MSDT [33], and chronic GVHD severity strongly correlates with negative impacts on patients’ HRQoL [34]. Although the current study does not include HRQoL analysis, cGVHD incidence and severity was comparable between the 2 groups and GRFS was higher in HIDT cohort. Further prospective studies investigating HRQoL are needed to evaluate if HID should replace MSD in some situation.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this prospective genetically randomized study is powered to detect that HIDT beats MSDT in regard to favorable anti-leukemia activity for ALL patients with pre-HSCT MRDpos. The current study paves the way to determine that HIDs should be the preferred choice regardless of available MSDs in a subgroup population. Our findings warrant further investigation and could inform decision-making and the development of donor-selection algorithms [2, 4, 14, 15, 18, 35]. More multi-center, prospective trials and mechanism studies are necessary to evaluate donor selection in regard to the anti-leukemia effect.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ALL:

-

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia

- AML:

-

Acute myeloid leukemia

- ATG:

-

Anti-thymocyte globulin

- Ara-c:

-

Cytosine arabinoside

- CAM:

-

Cyclophosphamide, cytosinearabinoside, mercaptopurine

- CART:

-

Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell immunotherapy

- cGVHD:

-

Chronic graft-versus-host disease

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CIR:

-

Cumulative incidence of relapse

- CR:

-

Complete remission

- CMV:

-

Cytomegalovirus

- Cy:

-

Cyclophosphamide

- DLI:

-

Donor lymphocyte infusion

- EBMT:

-

European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation

- EBV:

-

Epstein-Barr virus

- EORTC/MSG:

-

European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group

- GRFS:

-

GVHD-free, relapse-free survival

- GVHD:

-

Graft-versus-host disease

- GVL:

-

Graft-versus-leukemia

- HIDs:

-

Haploidentical donors

- HIDT:

-

Haploidentical donor transplantation

- HLA:

-

Human leukocyte antigen

- HRQoL:

-

Health-related quality of life

- HSCT:

-

Hemopoietic stem cell transplantation

- Hyper-CVAD [A]:

-

Cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and dexamethasone

- Hyper-CVAD [B]:

-

Methotrexate and cytosine arabinoside

- IFI:

-

Invasive fungal infection

- IFNα:

-

Interferon-α

- LAIPs:

-

leukemia-associated immunophenotypes

- LFS:

-

Leukemia-free survival

- MAE:

-

Cytosinearabinoside, mitoxantrone, and etoposide

- MFC:

-

Multiparameter flow cytometry

- MRD:

-

Minimal residual disease

- MSDs:

-

Matching sibling donors

- MSDT:

-

Matched sibling donor transplantation

- MTX:

-

Methotrexate

- MVA:

-

Multivariate analysis

- NRM:

-

Non-relapse mortality

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- PH:

-

Philadelphia chromosome

- post-HSCT MRDpos:

-

Post-transplantation minimal residual disease positivity

- pre-HSCT MRDpos:

-

Pre-transplantation minimal residual disease positivity

- RT-PCR:

-

Real-time polymerase chain reaction

- SCT:

-

Stem cell transplantation

- TKI:

-

Tyrosine kinase inhibitor

- URD:

-

Unrelated donor

- VDCLP:

-

Vincristine, daunorubicin, cyclophosphamide, L-asparaginase, and prednisone

- VDCP:

-

Vincristine, daunorubicin, cyclophosphamide, and prednisone

- VDLP:

-

Vincristine, daunorubicin, L-asparaginase, and prednisone

- VDP:

-

Vincristine, daunorubicin, and prednisone

References

Kanakry CG, Fuchs EJ, Luznik L. Modern approaches to HLA-haploidentical blood or marrow transplantation. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2016;13:10–24.

Wang Y, Chang YJ, Xu LP, Liu KY, Liu DH, Zhang XH, et al. Who is the best donor for a related HLA haplotype-mismatched transplant? Blood. 2014;124:843–50.

Wang Y, Liu QF, Xu LP, Liu KY, Zhang XH, Ma X, et al. Haploidentical versus matched-sibling transplant in adults with Philadelphia-negative high-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a biologically phase III randomized study. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:3467–76.

Chang YJ, Huang XJ. Is human leukocyte antigen-matched sibling donor transplant always better than haploidentical allograft? Semin Hematol. 2019;56:201–8.

Shouval R, Fein JA, Labopin M, Kroger N, Duarte RF, Bader P, et al. Outcomes of allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation from HLA-matched and alternative donors: a European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation registry retrospective analysis. Lancet Haematol. 2019;6:e573–e84.

Lu DP, Dong L, Wu T, Huang XJ, Zhang MJ, Han W, et al. Conditioning including antithymocyte globulin followed by unmanipulated HLA-mismatched/haploidentical blood and marrow transplantation can achieve comparable outcomes with HLA-identical sibling transplantation. Blood. 2006;107:3065–73.

Liu Y, Huang X, Fei Q, Xu L, Zhang X, Liu K, et al. Comparison analysis between haplo identical stem cell transplantation and matched sibling donor stem cell transplantation for high-risk acute myeloid leukemia in first complete remission. Sci China Life Sci. 2019;62:691–7.

Mariotti J, Devillier R, Bramanti S, Sarina B, Furst S, Granata A, et al. T Cell-Replete Haploidentical Transplantation with Post-Transplantation Cyclophosphamide for Hodgkin lymphoma relapsed after autologous transplantation: reduced incidence of relapse and of chronic graft-versus-host disease compared with HLA-identical related donors. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2018;24:627–32.

Gauthier J, Poire X, Gac AC, Leclerc M, Guillaume T, Chalandon Y, et al. Better outcome with haploidentical over HLA-matched related donors in patients with Hodgkin’s lymphoma undergoing allogeneic haematopoietic cell transplantation-a study by the Francophone Society of Bone Marrow Transplantation and Cellular Therapy. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2018;53:400–9.

Chang YJ, Wang Y, Liu YR, Xu LP, Zhang XH, Chen H, et al. Haploidentical allograft is superior to matched sibling donor allograft in eradicating pre-transplantation minimal residual disease of AML patients as determined by multiparameter flow cytometry: a retrospective and prospective analysis. J Hematol Oncol. 2017;10:134.

Wang Y, Liu DH, Xu LP, Liu KY, Chen H, Chen YH, et al. Superior graft-versus-leukemia effect associated with transplantation of haploidentical compared with HLA-identical sibling donor grafts for high-risk acute leukemia: an historic comparison. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2011;17:821–30.

Wang Y, Liu QF, Wu DP, Xu LP, Liu KY, Zhang XH, et al. Improved survival after offspring donor transplant compared with older aged-matched siblings for older leukaemia patients. Br J Haematol. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.16303.

Srour SA, Saliba RM, Bittencourt MCB, Perez JMR, Kongtim P, Alousi A, et al. Haploidentical transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia patients with minimal/measurable residual disease at transplantation. Am J Hematol. 2019;94:1382–7.

Kekre N, Antin JH. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation donor sources in the 21st century: choosing the ideal donor when a perfect match does not exist. Blood. 2014;124:334–43.

Tiercy JM. How to select the best available related or unrelated donor of hematopoietic stem cells? Haematologica. 2016;101:680–7.

Shem-Tov N, Peczynski C, Labopin M, Itala-Remes M, Blaise D, Labussiere-Wallet H, et al. Haploidentical vs. unrelated allogeneic stem cell transplantation for acute lymphoblastic leukemia in first complete remission: on behalf of the ALWP of the EBMT. Leukemia. 2019;34:283–92.

Brown PA, Shah B, Fathi A, Wieduwilt M, Advani A, Aoun P, et al. NCCN guidelines insights: acute lymphoblastic leukemia, Version 1.2017. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017;15:1091–102.

Xu L, Chen H, Chen J, Han M, Huang H, Lai Y, et al. The consensus on indications, conditioning regimen, and donor selection of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for hematological diseases in China-recommendations from the Chinese Society of Hematology. J Hematol Oncol. 2018;11:33.

Chang YJ, Xu LP, Wang Y, Zhang XH, Chen H, Chen YH, et al. Controlled, randomized, open-label trial of risk-stratified corticosteroid prevention of acute graft-versus-host disease after haploidentical transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1855–63.

Wang Y, Wu DP, Liu QF, Xu LP, Liu KY, Zhang XH, et al. Low-dose post-transplant cyclophosphamide and anti-thymocyte globulin as an effective strategy for GVHD prevention in haploidentical patients. J Hematol Oncol. 2019;12:88.

Zhao XS, Liu YR, Xu LP, Wang Y, Zhang XH, Chen H, et al. Minimal residual disease status determined by multiparametric flow cytometry pretransplantation predicts the outcome of patients with ALL receiving unmanipulated haploidentical allografts. Am J Hematol. 2019;94:512–21.

Mo XD, Zhang XH, Xu LP, Wang Y, Yan CH, Chen H, et al. A potentially effective treatment for minimal residual disease in acute leukemia/myelodysplastic syndrome after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015;21:1939–47.

Yan CH, Liu DH, Liu KY, Xu LP, Liu YR, Chen H, et al. Risk stratification-directed donor lymphocyte infusion could reduce relapse of standard-risk acute leukemia patients after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2012;119:3256–62.

Wang Y, Xu L, Yan C, Huang X. Modification of donor lymphocyte infusion: how to improve the outcome? Sci China Life Sci. 2019;62:1253–6.

Zhao X, Zhao X, Chen H, Qin Y, Xu L, Zhang X, et al. Comparative analysis of flow cytometry and RQ-PCR for the detection of minimal residual disease in Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2018;24:1936–43.

Wang Y, Chen H, Chen J, Han M, Hu J, Jiong H, et al. The consensus on the monitoring, treatment, and prevention of leukemia relapse after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in China. Cancer Lett. 2018;438:63–75.

Bar M, Wood BL, Radich JP, Doney KC, Woolfrey AE, Delaney C, et al. Impact of minimal residual disease, detected by flow cytometry, on outcome of myeloablative hematopoietic cell transplantation for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leuk Res Treatment. 2014;2014:421723.

Whitehill GD, Amarnath S, Muranski P, Keyvanfar K, Battiwalla M, Barrett AJ, et al. Adenosine selectively depletes alloreactive T cells to prevent GVHD while conserving immunity to viruses and leukemia. Mol Ther. 2016;24:1655–64.

Berry DA, Zhou S, Higley H, Mukundan L, Fu S, Reaman GH, et al. Association of minimal residual disease with clinical outcome in pediatric and adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:e170580.

Walker I, Panzarella T, Couban S, Couture F, Devins G, Elemary M, et al. Pretreatment with anti-thymocyte globulin versus no anti-thymocyte globulin in patients with haematological malignancies undergoing haemopoietic cell transplantation from unrelated donors: a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3, multicentre trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:164–73.

Rao AV, Valk PJ, Metzeler KH, Acharya CR, Tuchman SA, Stevenson MM, et al. Age-specific differences in oncogenic pathway dysregulation and anthracycline sensitivity in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5580–6.

Sykes M, Preffer F, McAfee S, Saidman SL, Weymouth D, Andrews DM, et al. Mixed lymphohaemopoieticchimerism and graft-versus-lymphoma effects after non-myeloablative therapy and HLA-mismatched bone-marrow transplantation. Lancet. 1999;353:1755–9.

Mo XD, Xu LP, Liu DH, Chen YH, Han W, Zhang XH, et al. Patients receiving HLA-haploidentical/partially matched related allo-HSCT can achieve desirable health-related QoL that is comparable to that of patients receiving HLA-identical sibling allo-HSCT. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2012;47:1201–5.

Mo XD, Xu LP, Liu DH, Chen YH, Zhang XH, et al. Health related quality of life among patients with chronic graft-versus-host disease in China. Chin Med J (Engl). 2013;126:3048–52.

Ciurea SO, Al Malki MM, Kongtim P, Fuchs EJ, Luznik L, Huang XJ, et al. The European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) consensus recommendations for donor selection in haploidentical hematopoietic cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2020;55:12–24.

Acknowledgements

We thank all of the faculty members who participated in these studies. We would also like to thank San Francisco Edit (www.sefedit.net) for assistance in editing this manuscript.

Funding

This work was partly supported by grants from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2017YFA0104500 and 2019YFC0840606), Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Commission (Z181100009618032), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81621001, 81530046, 81770189, and 81670186), and Peking University Clinical Scientist Program (BMU2019LCKXJ003).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Contribution: X.-J.H. designed the study; Y.-J.C. and Y. W. collected data; Y.-J.C., Y. W., and X.-J.H. analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript; all authors contributed to data interpretation, manuscript preparation, and approval of the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Peking University People’s Hospital. The study is registered at http://clinicaltrials.gov/ NCT02185261. Informed consent was obtained from each patient.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declared that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Figure S1.

Outcome of allogeneic stem cell transplantations in four groups classified according to pre-transplantation MRD and transplant modalities (n=725). (A) cumulative incidence of leukemia relapse, (B) non-relapse mortality, (C) leukemia-free survival, and (D) overall survival. Abbreviations: Haplo-SCT=haploidentical stem cell transplantation; MSDT=human leukocyte antigen-matched sibling donor transplantation; MRD=measurable residual disease.

Additional file 2: Table S1.

Patient and donor characteristics (n=517)*. Table S2. Transplant outcomes between patients with negative pre-transplantation MRD who underwent Haplo-SCT and those who received MSDT (n=517).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Chang, YJ., Wang, Y., Xu, LP. et al. Haploidentical donor is preferred over matched sibling donor for pre-transplantation MRD positive ALL: a phase 3 genetically randomized study. J Hematol Oncol 13, 27 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-020-00860-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-020-00860-y