Abstract

Background

Depression is associated with chronic physical illnesses and negatively affects health outcomes. However, it often goes undiagnosed and untreated. We investigated the prevalence of depression among adult type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) patients attending non-communicable diseases (NCD) clinics in Lilongwe, Malawi, and estimated the level of routine detection by NCD clinicians. This study set out to determine the prevalence of major depression and its detection among adult type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) patients attending NCD clinics in Lilongwe, Malawi.

Methods

In a cross-sectional study design, 323 T2DM patients aged ≥ 18 years were screened for depression with the Patient Health Questionnare-9 (PHQ-9) followed by diagnostic assessment with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID). We analysed the association between presence of major depression and sociodemographic factors using logistic regression.

Results

Three quarters of the participants (76%) were females. The participants’ ages ranged from 21–79 years. Of the 323 participants, 58 (18%) met criteria for DSM-IV major depression. None of the cases of major depression had been identified by the NCD clinicians. Major depression was found not to be significantly associated with any of the sociodemographic factors.

Conclusions

We found that depression is common among NCD clinic attendees with T2DM in Malawi, and poorly detected by NCD clinicians. Given the high prevalence and challenges in clinical identification, integration of depression screening with a standardized validated tool should be a high priority so as to link patients to appropriate services.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Depression is associated with chronic physical illnesses and negatively affects health outcomes [1, 2]. Few affected people access appropriate treatment as depression is often undiagnosed. Diabetes mellitus is a common chronic disease, and in Malawi, the prevalence of raised fasting blood glucose or being currently on medication for diabetes based on the 2009 STEPS survey was 5.6% [3]. A systematic review shows that the prevalence of depression in patients with diabetes mellitus ranges between 6 and 43% [4]. The wide range of reported prevalence estimates may be due to differences in assessment tools and variation in the types of patients in the studies cohorts. Depression in patients with diabetes is often associated with poor glycaemic control, poor adherence to medication, and rapid development of complications [5,6,7]. For instance a diabetic complication such as diabetic neuropathy is associated with reduced quality of life, poor sleep, depression and anxiety [8]. Comorbid depression is associated with a decrease in metabolic control, poor adherence to medication and diet regimens, a reduction in quality of life, and an increase in health care expenditures. Consequently, poor metabolic control may exacerbate depression and diminish response to depression treatment [9]. Evidence indicates that depression complicate diabetes management, increase the length of hospital stays, and almost doubled the cost of diabetes management [10]. Literature also suggests that duration of diabetes influences depressive symptoms [11]. Furthermore, depression is often undiagnosed and untreated in this patient population [12,13,14,15,16]. Despite the high prevalence and its impact on diabetes, the potential for depression treatment to improve diabetes care outcomes has received little attention in both low and middle income countries (LMIC) [17,18,19], and high income countries. In LMIC this lack of attention is partly because of limited capacity in depression management and the absence of any routine practice to identify and manage depression in NCD care.

Malawi is facing a growing challenge of non-communicable diseases (NCD), including diabetes mellitus [20,21,22,23]. Furthermore, Malawi has a large treatment gap for common mental disorders including depression with a limited number of mental health professionals serving a population of > 18 million. Prevalence of depression between 19 and 30% has been reported among adult primary care attendees in Malawi [24, 25]; none of these cases of depression were identified by clinicians in routine care [24, 25]. There are no published data regarding the prevalence of depression among patients with diabetes attending NCD clinics, or of levels of detection by clinic staff. Currently, there is no routine screening for depression in the NCD clinics in the country.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of major depression and its detection by clinicians among adult type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) patients attending NCD clinics in Lilongwe, Malawi.

Materials and methods

Setting and participants

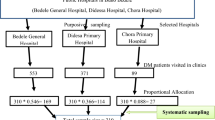

We carried out a cross-sectional study from December 2017 till April 2018 among patients suffering from diabetes mellitus. We conducted the study at two diabetes clinics in two facilities within Lilongwe district. The catchment population of the two clinics and the staffing levels have been described elsewhere [26]. The patients attending to the clinics are not routinely screened for any mental health problems. We included adult patients with T2DM who provided consent to participate in the study. The exclusion criteria included patients with Type 1 diabetes mellitus, patients who were too ill, and those suffering from an illness causing inability to communicate.

Data collection

We collected data from consecutive adult participants with T2DM attending the diabetes clinic at the two facilities. We chose a consecutive sampling technique because it includes all patients who are accessible within the defined study time period [27]. Participants were recruited after they had seen an NCD clinician for routine care. Participants provided written consent after which socio-demographic data was collected and were then screened using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) [28] by a research assistant. The PHQ-9 is a 9-item screening tool which is widely used in clinical practice and research. The PHQ-9 Chichewa version has been validated in Malawi and described elsewhere [29]. All participants who underwent PHQ-9 screening were requested to meet the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) [30] interviewer after their clinical consultation. The participants later completed the diagnostic interview administered by the SCID interviewer who was masked from the PHQ-9 scores of the participants. The SCID was used to make a diagnosis of depression among the patients.

The clinicians working at the two facilities' NCD clinics were all clinical officers (COs). Clinical officers are para-medicals who are trained to provide general medico-surgical care; they are trained for four years consisting of 3 years’ college education followed by a year of internship [31,32,33,34]. The clinicians in this study had basic mental health training as part of their clinical officer’s training and were not given any extra training for this study. The clinicians reviewed the patients and made entries in the patient's medical booklet (commonly known as a health passport [35]) as well as NCD master-cards (chronic care medical charts which are kept at the clinic). They recorded the presenting complaint, history of the presenting illness, any pertinent past history, findings of the physical examination, diagnosis, any investigations requested and treatment provided. To assess whether depression had been detected as part of routine clinical care, data on the consultation written by the clinician was extracted from the health passports, to ascertain whether a diagnosis of depression was made or not during the clinical encounter.

Data analysis

For screening data obtained using the PHQ-9, the presence of depressive symptoms was defined as having a total score of at least 5 (PHQ-9 total score ≥ 5). PHQ-9 total scores were categorised as follows: [36, 37].

-

0–4No or minimal depressive symptoms

-

5–9Mild depressive symptoms

-

10–19Moderate depressive symptoms

-

20–27Severe depressive symptoms

DSM IV diagnoses obtained using the SCID were: no depression, minor depression and major depression. Sociodemographic factors measured were: age, sex, education, employment status and marital status. We analysed the association between presence of major depression and sociodemographic factors using logistic regression. Statistical analysis was carried out using both SPSS version 20.0 and Stata 14.

Ethical approval

The University of Malawi College of Medicine Research and Ethics Committee (COMREC) approved the study protocol. We obtained written informed consent from every participant and fingerprint impressions were taken from consenting participants who could not write. Privacy was maintained during the interviews with participants at the health facilities as the interviews were conducted in a room which provided both visual and audio privacy.

Results

Demographic data

Our study included all 323 participants with type 2 diabetes mellitus who were approached, consented and completed the questionnaires (PHQ-9 and SCID); there were no refusals. 244 (76%) were female. Participants’ ages ranged from 21–79 years with a mean (standard deviation) of 54.0 (11.4). 8.4% of the participants were illiterate. Table 1 shows patients’ characteristics.

Severity score of depressive symptoms and prevalence of probable depression based on PHQ-9

The distribution of severity of depressive symptoms based on the PHQ-9 scores is shown in Table 2.

Prevalence of depression based on SCID

The prevalence of DSM IV depression diagnoses based on the SCID were: no depression 58.2% (n = 190), minor depression 23.8% (n = 75) and major depression 18% (n = 58).

Distribution by major depression status and socio-demographic characteristics based on multiple logistic regression analyses

Major depression was found not to be significantly associated with any of the sociodemographic variables: education level (p < 0.07) age, gender (p < 0.47), marital status (p < 0.92), and current employment status (p < 0.34) (Table 3).

Detection of depression by NCD Clinicians

None of the participants were diagnosed as having depression during routine clinical assessment by the NCD clinicians. This included the 58 participants who were identified as having major or minor depression using SCID.

Discussion

Recognising a mental disorder such as depression in patients with physical illness is important in clinical management and improving patients’ clinical outcomes. In this population of adult type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) patients attending non communicable diseases (NCD) clinics in Lilongwe, Malawi, we investigated the prevalence and rate of routine detection of depression, finding that 18% of participants met criteria for major depression, none of whom were detected in routine practice by the NCD clinicians.

Prevalence of depression among people with T2DM

Evidence indicate that 18%–25% of people with T2DM will meet DSM criteria for a major depressive episode using the SCID [11]. The prevalence of major depression in T2DM in our study is comparable to prevalence estimates of 19% and 30% found in two studies of general primary care outpatient attendees in Malawi [24, 25]. There is some overlap with the populations in the previous studies as these were conducted in facilities that did not have dedicated NCD clinics, so will have included patients with T2DM. The finding of our study that one-fifth of patients with T2DM (18%) suffered from major depression is similar to the findings of a systematic review by Roy and Lloyd where the they found a prevalence of 19.1% (range 6.5–33%) [4] however the finding is considerably higher compared to that of a collaborative study carried out in 14 countries which found a prevalence of 10.6% [38]. The rate of major depression in this study is also comparable to rates of depression in studies from Nigeria with a prevalence of 19.4% based on the SCID [39] and from Ethiopia with a prevalence of 17% on the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) [40].

In contrast to our study, several studies in other African countries have shown higher prevalence of depression among T2DM patients. A study in Morocco found that patients with T2DM had higher prevalence of major depression (33.1%) [41] while studies in South Africa found and in Egypt found 46% and 32% respectively [39]. Similarly a systematic review conducted in Ethiopia showed that the prevalence of depression among T2DM patients was 39.73% [42]. In other LMICs the findings of higher prevalence of major depression are also similar. For instance a multi-centre study conducted in Pakistan found that 43.5% of T2DM patients had depression [43]. A Mexican study also found a higher prevalence of 48.27% [44] compared to our study.

Depression screening and diagnosis

Depression is diagnosed using a structured clinical interview, such as the SCID and other interviews such as Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). However the interviews vary in terms of length as such they can be time-consuming therefore depression can be screened accurately using a few questions such as the PHQ-9 [11]. A variety of screening tools for depression are available, however few have been developed for use in LMIC settings [45]. In our study, the majority of patients (34.4%) had mild depression, 22.6% had moderate and 2.2% had severe depression based on PHQ-9 scores. Our finding is similar to findings in other LMICs, for instance a study in Iran that showed that 38% of patients had mild depression, 30% had moderate depression, and 13% had severe depression on the BDI [46]. Further, the findings are also similar to a study in Tanzania which showed that 22.1% had mild depression, and 8.2% had moderate depression while none had severe depression based on the PHQ-9 [6]. An Indian study also found almost similar finding which showed that 25% had mild depression, 12.5% had moderate depression, and 1.3% had severe depression on the Major Depression Inventory (MDI) [7]. In contrast to our study, a Bangladesh study found that majority of patients (20.2%) had severe depression rather than mild to moderate depression (14.6%) using the Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale [47]. One of the reasons could be because of the relatively small size of the data sample in the Bangladesh study compared to our study and the other reason could be the use of different tools.

Interventions for comorbid depression and diabetes

Most low and middle income countries have a large treatment gap for common mental disorders including depression [48]. Studies suggest that one way of reducing the treatment gap is the integration of mental health into other health care services [49, 50]. Integrating depression screening and treatment into primary care to improve access to mental health services mostly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) is being advocated [51]. Furthermore, it has been suggested that mental health care and NCD care should be offered together in primary care platforms due to the growing burden of both [52]. There is evidence that demonstrates the effectiveness of a range of mental disorder interventions, including medicines, psychological treatments, and social interventions delivered by non-mental health specialist in LMICs [53]. A systematic review of collaborative care for patients with comorbid conditions provides evidence to support the effectiveness of integrated care in improving depression outcomes and improved adherence to treatment for both depression and diabetes [54].

Despite the advocacy of the initiative, many barriers to integration exist. For instance, a potential barrier to integrating screening into routine practice and ensuring patients with depression receive the necessary required care is that many health workers in LMICs are not trained or do not have time to screen for depression when seeing patients [45].

Despite the high prevalence of depression, none of the patients who were diagnosed with major depression by the research team using the SCID were detected and diagnosed as such by the NCD clinician. This finding agrees with other studies conducted among patients with T2DM [12,13,14,15,16]. The reasons for non-detection of depression in this setting could be due to lack of knowledge and skills, lack of integration of mental health in NCD care and lack of routine screening for depression. These reasons are in line with the results from general primary care clinics studies in Malawi [24, 25]. The failure to detect and manage depression will affect management of T2DM as evidenced in other studies [15, 16]. Several studies have demonstrated that depression treatment effectively reduces the severity of depression in patients with diabetes and also produces better glycaemic control [55], significantly improve HbA1C [56] restore mental health and improve medical outcome [57]. As such if depression in patients with diabetes is not recognized, it will go untreated and consequently the medical and mental health outcomes will be negatively affected. Detecting depression in the clinical setting is aided by validated tools that can be easily administered with limited resources. Improved detection of depression through the use of the PHQ-9 by the clinicians would lead to the initiation of treatment or referral to mental health services for treatment which may consequently lead to improved outcomes and lower complications. Therefore, NCD clinicians have to be equipped with the necessary knowledge and skills in detection and treatment.

Based on multivariable logistic regression, the sociodemographic factors including age, gender, education, marital status and employment were not associated with depression. Related studies have gotten varying results with many similarly finding no association with this set of factors [1, 17, 58,59,60,61,62,63]; but, some individual studies showing associations with them [64,65,66,67]. In the present study, three quarters of the participants were females. However, it is unlikely that this had an influence on the results for females as there was no evidence of a difference in the odds of depression between the two genders. The over representation of females in our study is similar to other studies like the Malawi STEPS Survey [68], which may be due to the increased health care seeking behaviour by females relative to males.

One notable strength of this study is that it used a gold standard, the SCID for depression that had previously been used in different studies in Malawi. Furthermore, the quality of administration of the PHQ-9 and of the SCID was very good as the research assistants had training in administration of the research tools and received regular supervision from the principal investigator. To our knowledge, this is the first study analyzing depression among patients with diabetes in Malawian population.

Study limitations

The results of this study should however be interpreted in light of limitation. The limitation of this study is that the participants were selected through a consecutive sampling technique from two specialized NCD clinics in Lilongwe which may not be representative of the wider population. However, despite this limitation, the paper fills an important knowledge gap regarding the prevalence and detection of depression among patients with diabetes in Malawi, given the dearth of evidence in LMIC settings. In this regard, the paper shows a crucial gap and has the potential to stimulate policy makers and clinicians to develop interventions to improve detection of depression among patients with diabetes.

Conclusions

Depression is prevalent among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus attending NCD clinics in Malawi. The evidence from this study shows that depression is undiagnosed in patients with diabetes in NCD clinics. Clinicians in NCD clinics must know how to screen for depression and ensure availability of treatment. Clinicians should consider using screening tools to identify depression among patients with type 2 diabetes. Furthermore, there must be a parallel focus on establishing mental health services to which these identified patients could be connected. It is therefore important to explore ways to identify depression in NCD clinics.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Black SA, Markides KS, Ray LA. Depression predicts increased incidence of adverse health outcomes in older Mexican Americans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(10):2822–8.

Akpalu J, Yorke E, Ainuson-Quampah J, Balogun W, Yeboah K. Depression and glycaemic control among type 2 diabetes patients: a cross-sectional study in a tertiary healthcare facility in Ghana. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18:357.

Msyamboza KP, Mvula CJ, Kathyola D. Prevalence and correlates of diabetes mellitus in Malawi: population-based national NCD STEPS survey. BMC Endocrine Disord. 2014;14(1):41.

Roy T, Lloyd CE. Epidemiology of depression and diabetes: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2012;142:S8–21.

Moussavi S, Chatterji S, Verdes E, Tandon A, Patel V, Ustun B. Depression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: results from the World Health Surveys. Lancet. 2007;370(9590):851–8.

Khan ZD, Lutale J, Moledina SM. Prevalence of depression and associated factors among diabetic patients in an outpatient diabetes clinic. Psychiatry J. 2019;2019:2083196.

Mathew C, Dominic M, Isaac R, Jacob J. Prevalence of depression in consecutive patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus of 5-year duration and its impact on glycemic control. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16(5):764–8.

Vinik A, Casellini C, Nevoret ML. Diabetic Neuropathies. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Boyce A, Chrousos G, de Herder WW, Dungan K, et al. editors. Endotext. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc. Copyright © 2000–2020, MDText.com, Inc.; 2000.

Lustman P, Clouse R. Depression in diabetic patients: the relationship between mood and glycemic control. J Diabetes Complicat. 2005;19:113–22.

Boulanger L, Zhao Y, Foster TS, Fraser K, Bledsoe SL, Russell MW. Impact of comorbid depression or anxiety on patterns of treatment and economic outcomes among patients with diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009;25(7):1763–73.

Darwish L, Beroncal E, Sison MV, Swardfager W. Depression in people with type 2 diabetes: current perspectives. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2018;11:333–43.

Katon W, Von Korff M, Ciechanowski P, Russo J, Lin E, Simon G. Behavioral and clinical factors associated with depression among individuals with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:914–20.

Alshehri AA, Al-Gadouri MA, Abdulrahim FM, Fatani BZ, Alsaedi AJ, Al-Daham D, et al. Prevalence of depression among diabetic patients in Makkah. Egypt J Hosp Med. 2018;71(1):2243–9.

Li C, Ford ES, Zhao G, Ahluwalia IB, Pearson WS, Mokdad AH. Prevalence and correlates of undiagnosed depression among US adults with diabetes: the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2006. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2009;83(2):268–79.

Lin EH, Rutter CM, Katon W, Heckbert SR, Ciechanowski P, Oliver MM, et al. Depression and advanced complications of diabetes: a prospective cohort study. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(2):264–9.

Lin EH, Katon W, Von Korff M, Rutter C, Simon GE, Oliver M, et al. Relationship of depression and diabetes self-care, medication adherence, and preventive care. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(9):2154–60.

Raval A, Dhanaraj E, Bhansali A, Grover S, Tiwari P. Prevalence & determinants of depression in type 2 diabetes patients in a tertiary care centre. Indian J Med Res. 2010;132(2):195.

Reddy P, Philpot B, Ford D, Dunbar JA. Identification of depression in diabetes: the efficacy of PHQ-9 and HADS-D. Br J Gen Pract. 2010;60(575):e239–45.

Bryan C, Songer T, Brooks MM, Rush AJ, Thase ME, Gaynes B, et al. The impact of diabetes on depression treatment outcomes. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32(1):33–41.

Gowshall M, Taylor-Robinson SD. The increasing prevalence of non-communicable diseases in low-middle income countries: the view from Malawi. Int J General Med. 2018;11:255–64.

Msyamboza KP, Ngwira B, Dzowela T, Mvula C, Kathyola D, Harries AD, et al. The burden of selected chronic non-communicable diseases and their risk factors in Malawi: nationwide STEPS survey. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(5):e20316.

Soliman EZ, Juma H. Cardiac disease patterns in Northern Malawi: epidemiologic transition perspective. J Epidemiol. 2008;18(5):204–8.

Payne CF, Mkandawire J, Kohler HP. Disability transitions and health expectancies among adults 45 years and older in Malawi: a cohort-based model. PLoS Med. 2013;10(5):e1001435.

Kauye F, Jenkins R, Rahman A. Training primary health care workers in mental health and its impact on diagnoses of common mental disorders in primary care of a developing country, Malawi: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Psychol Med. 2014;44(03):657–66.

Udedi M. The prevalence of Depression among patients and its detection by primary health care workers at Matawale Health Centre (Zomba). Malawi Med J. 2014;26(2):34–7.

Udedi MM, Pence BW, Kauye F, Muula AS. Study protocol for evaluating the effectiveness of depression management on gylcaemic control in non-communicable diseases clinics in Malawi. BMJ Open. 2018;8(10):e021601.

Mathieson K. Making sense of biostatistics: types of nonprobability sampling. J Clin Res Best Pract. 2014;10(10).

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–13.

Udedi M, Muula AS, Stewart RC, Pence BW. The validity of the patient health Questionnaire-9 to screen for depression in patients with type-2 diabetes mellitus in non-communicable diseases clinics in Malawi. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19(1):81.

First MB, Spitzer R, Gibbon M, Williams JB. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV clinical version (SCID-I/CV). Washington DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1997.

Jiskoot P. On-the-job training of clinical officers in Malawi. Malawi Med J. 2008;20(3):74–7.

Darwinkel MC, Nduru JM, Nabie RW, Aswani JA. Evaluating the role of clinical officers in providing reproductive health services in Kenya. Hum Resour Health. 2018;16(1):31.

Wilson A, Lissauer D, Thangaratinam S, Khan KS, MacArthur C, Coomarasamy A. A comparison of clinical officers with medical doctors on outcomes of caesarean section in the developing world: meta-analysis of controlled studies. BMJ. 2011;342:d2600.

Muula AS. Case for clinical officers and medical assistants in Malawi. Croat Med J. 2009;50(1):77–8.

Weston W, Smedley J, Bennett A, Mortimer K. The Cooking and Pneumonia Study (CAPS) in Malawi: implementation of remote source data verification. PloS ONE. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0155966.

Lowe B, Kroenke K, Herzog W, Grafe K. Measuring depression outcome with a brief self-report instrument: sensitivity to change of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). J Affect Disord. 2004;81(1):61–6.

Lowe B, Unutzer J, Callahan CM, Perkins AJ, Kroenke K. Monitoring depression treatment outcomes with the patient health questionnaire-9. Med Care. 2004;42(12):1194–201.

Lloyd CE, Nouwen A, Sartorius N, Ahmed HU, Alvarez A, Bahendeka S, et al. Prevalence and correlates of depressive disorders in people with Type 2 diabetes: results from the International Prevalence and Treatment of Diabetes and Depression (INTERPRET-DD) study, a collaborative study carried out in 14 countries. Diabet Med. 2018;35:760–9.

Mendenhall E, Norris SA, Shidhaye R, Prabhakaran D. Depression and type 2 diabetes in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;103(2):276–85.

Mossie TB, Berhe GH, Kahsay GH, Tareke M. Prevalence of depression and associated factors among diabetic patients at Mekelle City, North Ethiopia. Indian J Psychol Med. 2017;39(1):52–8.

Bensbaa S, Agerd L, Boujraf S, Araab C, Aalouane R, Rammouz I, et al. Clinical assessment of depression and type 2 diabetes in Morocco: economical and social components. J Neurosc Rural Pract. 2014;5(03):250–3.

Teshome HM, Ayalew GD, Shiferaw FW, Leshargie CT, Boneya DJ. The prevalence of depression among diabetic patients in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis, 2018. Depress Res Treat. 2018;2018:6135460.

Khuwaja AK, Lalani S, Dhanani R, Azam IS, Rafique G, White F. Anxiety and depression among outpatients with type 2 diabetes: A multi-centre study of prevalence and associated factors. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2010;2(1):72.

Tovilla-Zarate C, Juarez-Rojop I, Peralta Jimenez Y, Jimenez MA, Vazquez S, Bermudez-Ocana D, et al. Prevalence of anxiety and depression among outpatients with type 2 diabetes in the Mexican population. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(5):e36887.

Ali G-C, Ryan G, De Silva MJ. Validated screening tools for common mental disorders in low and middle income countries: a systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(6):e0156939.

Shahrakivahed A, Moushtagh Z, Firozkohi M, Jahantigh M. Frequency and severity of depression in diabetic patients referred to the diabetic center of Zabol. Interdiscip J Contemp Res Bus. 2012;4(1):935.

Rahman M, Rahman MA, Flora MS, Karim R, Zaman MR. Depression and its association with socio-demographic characteristics among type 2 diabetes mellitus patients of Bangladesh. Mymensingh Med J. 2012;21(3):490–6.

Patel V, Maj M, Flisher AJ, De Silva MJ, Koschorke M, Prince M, et al. Reducing the treatment gap for mental disorders: a WPA survey. World Psychiatry. 2010;9(3):169–76.

Patel V, Thornicroft G. Packages of care for mental, neurological, and substance use disorders in low-and middle-income countries: PLoS Medicine Series. PLoS Med. 2009. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000160.

Lancet Global Mental Health Group. Scale up services for mental disorders: a call for action. Lancet. 2007;370(9594):1241–52.

WHO. The World Health Report 2001: mental health: new understanding, new hope. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001.

Ngo VK, Rubinstein A, Ganju V, Kanellis P, Loza N, Rabadan-Diehl C, et al. Grand challenges: integrating mental health care into the non-communicable disease agenda. PLoS Med. 2013;10(5):e1001443.

Patel V, Chatterji S. Integrating mental health in care for noncommunicable diseases: an imperative for person-centered care. Health Aff. 2015;34:1498–505.

Huang Y, Wei X, Wu T, Chen R, Guo A. Collaborative care for patientswith depression and diabetes mellitus:a systematic review and metaanalysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:260.

Lustman PJ, Freedland KE, Griffith LS, Clouse RE. Fluoxetine for depression in diabetes: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2000;23(5):618–23.

Echeverry D, Duran P, Bonds C, Lee M, Davidson MB. Effect of pharmacological treatment of depression on A1C and quality of life in low-income Hispanics and African Americans with diabetes: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(12):2156–60.

Lustman PJ, Griffith LS, Clouse RE, Freedland KE, Eisen SA, Rubin EH, et al. Effects of nortriptyline on depression and glycemic control in diabetes: results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Psychosom Med. 1997;59(3):241–50.

De Groot M, Anderson R, Freedland KE, Clouse RE, Lustman PJ. Association of depression and diabetes complications: a meta-analysis. Psychosom Med. 2001;63(4):619–30.

Rahman M, Rahman MA, Flora MS, Rakibuz-Zaman M. Depression and associated factors in diabetic patients attending an urban hospital of Bangladesh. Int J Collab Res Intern Med Public Health. 2011;3(1):65.

Nasser J, Habib F, Hasan M, Khalil N. Prevalence of depression among people with diabetes attending diabetes clinics at primary health settings. Bahrain Med Bull. 2009;31:1–7.

Guruprasad K, Niranjan M, Ashwin S. A study of association of depressive symptoms among the type 2 diabetic outpatients presenting to a tertiary care hospital. Indian J Psychol Med. 2012;34(1):30.

Lloyd CE, Dyer PH, Barnett AH. Prevalence of symptoms of depression and anxiety in a diabetes clinic population. Diabet Med. 2000;17:198–202.

Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, Clouse RE, Lustman PJ. The prevalence of comorbid depression in adults with diabetes. A meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2001a;24(6):1069–78.

Sweileh WM, Abu-Hadeed HM, Al-Jabi SW, Sa’ed HZ. Prevalence of depression among people with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a cross sectional study in Palestine. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):163.

Larijani B, Bayat M, Gorgani MK, Bandarian F, Akhondzadeh S, Sadjadi SA. Association between depression and diabetes. German J Psychiatry. 2004;7(3):62–5.

Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, Clouse RE, Lustman PJ. The prevalence of comorbid depression in adults with diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2001b;24:1069–78.

Poongothai S, Pradeepa R, Ganesan A, Mohan V. Prevalence of depression in a large urban South Indian population—The Chennai Urban Rural Epidemiology study (CURES–70). PLoS ONE. 2009;4(9):e7185.

MoH, WHO. Malawi National STEPS Survey for chronic non-communicable diseases and their risk factors. 2010.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express our sincere gratitude to DELTAS Africa Initiative through the African Mental Health Research Initiative (AMARI) for their financial support of this study. We would also like to thank the patients for their participation in the study. Finally, we would like to thank the research assistants who were responsible for consenting patients and data collection.

Funding

This study presents independent work supported through the DELTAS Africa Initiative [DEL-15-01]. The DELTAS Africa Initiative is an independent funding scheme of the African Academy of Sciences (AAS)’s Alliance for Accelerating Excellence in Science in Africa (AESA) and supported by the New Partnership for Africa’s Development Planning and Coordinating Agency (NEPAD Agency) with funding from the Wellcome Trust [DEL-15-01] and the UK government. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of AAS, NEPAD Agency, Wellcome Trust or the UK government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MU, ASM and BWP were involved in the conceptualization of the study. MU, ASM, BWP and RCS supported the study implementation. MU analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. ASM, RCS and BWP edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The ethical approval for the study was obtained from the College of Medicine Research and Ethics Committee (COMREC). All participants were provided with the necessary information of the study. We obtained written informed consent from the participants prior to data collection.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Udedi, M., Pence, B.W., Stewart, R.C. et al. Detection and prevalence of depression among adult type 2 diabetes mellitus patients attending non-communicable diseases clinics in Lilongwe, Malawi. Int J Ment Health Syst 14, 79 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-020-00413-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-020-00413-3