Abstract

Background

Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) genotypes concordance among sexual couples has been evaluated in many investigations with considerable variations in the concordance. However, no such study has carried out between Iranian couples yet.

Methods

Urogenital specimen from both males and females of couples were taken and transferred to Nilou laboratory for molecular analysis. HPV DNA extraction and typing were carried out using cobas 4800 platform. Demographic and virological data were analyzed afterwards.

Results

One hundred fourteen couples were enrolled in the study. The mean age of participants were 36 ± 8 and 32 ± 7 for males and females, respectively. 64 (28%) of specimens were positive for at least one HPV genotype. The positive rates within genders were 30.7 and 25.4% for females and males, respectively with a considerable association (P value 0.021). Within the positive samples, 13(5.7%), 8 (7%) and 31(13.5%) were belonged to 16, 18 and other HR genotypes. 59 (51.8%) couples who were negative for HPV showed negative concordance. Of the total positive HPV patients (55 couples, 48.2%), 9 (16.3%) couples had positive concordance and the rest of 46 (83.7%) couples (either of spouse being negative and the other being positive for HPV) showed neither kinds of concordance.

Conclusion

Recognition of the dynamics of HPV infection not only in women, but in their sexual partners could impact the implementation of preventive measures like HPV vaccination for cervical cancer and other HPV-related diseases for both sexual partners.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Worldwide, HPV infection accounts for an estimated 530,000 cervical cancer cases as well as 270,000 deaths annually occurring substantially in developing countries [1]. HPV also is the fundamental vehicle of vulvar and vaginal cancer in women and penile cancer in men. It is estimated that 40% of penile carcinomas are attributed to infection with high risk HPV [2,3,4] and approximately, 20% of all men (reaching 70% in some age groups), especially among individuals between 15 and 24 years of age are infected with HPV-infection [1]. Sexual behavior characteristics in both women and men are key determinants of HPV infection, worldwide. Moreover, previous reports confirmed that the sexual behavior of males can influence the risk of cervical cancer in their sexual partners [4,5,6,7]. The detected prevalence of HPV infection in male partners of women who were positive for HPV and/or cervical intraepithelial neoplasia or squamous carcinoma, ranged between 23 and 73% in several reports [4,5,6, 8]. Although compared to women, HPV infection may be associated with lower mortality and morbidity in men, however, due to its association with genital warts, penile, anorectal and oropharyngeal cancers as well as to the risk of HPV transmission to their female sexual partners research in this field remains essential [9,10,11] Accordingly, females partners of men having penile cancer showed cervical cancer prevalence eight times higher, whereas male partners of women having cervical cancer showed higher risk of developing penile cancer [12]. Transmission can occur easily between sexual partners, and in many cases, multiple transmission incidence may occur within a couple without being detected in either partner [5, 6, 13, 14]. The HPV type concordance between sex partners has been investigated in previous reports although with evident variations in the concordance [15,16,17,18]. Substantial variations in HPV type concordance are obvious, which may be explained by differences in the variety of HPV types examined, the different methodologies used for sampling (especial for men) and the population studied. Moreover, some investigations have recognized that HPV type concordance may be related to the concentration of viral DNA [15]. Evidence about HPV prevalence and its concordance in couples is of supreme importance for the evaluation of the impact of prophylactic vaccines against HPV and to monitor the spreading of specific HPV types before and after the introduction of HPV vaccines in populations. However, no investigation has evaluated the concordance of HPV types between couples or the prevalence of HPV infection in sexual partners of women in Iran.

The aims of the present survey were to determine HPV prevalence in heterosexual couples and to evaluate HPV type-specific concordance in a predominantly monogamous population.

Methods

Study population and specimen collection

This study was a longitudinal, cross sectional investigation on the prevalence of type-specific HPV concordance in sexually active couples during 2017–2018. To recognize the couples, men files were reviewed firstly. This was due to the fact that women consisting a majority of referrals to Nilou laboratory and finding couples through female files was troublesome. The inclusion criteria were a steady female partner (at least for the last 6 months even if they were not living in the same house) and, if so, whether they would invite their partner to join the couples’ survey. According to the Fig. 1, 487 men’s files were registered for HPV typing in Nilou Genetic Laboratory during 2017–2018. One hundred ninety-three single men were excluded. Also, 180 couples were dropped out after successfully meeting the inclusion criteria due to unwillingness to participation. Thus, a total of 114 sex partner participants were enrolled in the current investigation (Fig. 1).

A written informed consent guaranteeing confidentiality was taken from each patient. The study was approved by the National Ethics Committee for Biomedical Research affiliated to The Ministry of Health and Medical Education. According to HPV testing results, couples categorized into: positive concordance (both partners sharing the same HPV genotype), negative concordance (both being negative for HPV) and neither of discordance (when either of spouse being positive and the other being negative for HPV).

Sampling

The epithelial cells from the urinary meatus, frenulum of prepuce and glance of penis were obtained using a cytobrush, this was cut and inserted in thinprep tubes and tested immediately. For women, cervical scrapes were collected by sampling the ectocervix and endocervix with a cytobrush and cervical scrapes were also inserted in a tube containing lysis buffer. Alternatively, cervical samples were taken by a gynecologist from the endocervix and ectocervix areas with a sterile cytobrush and subsequently transferred to Nilou laboratory.

HPV testing

The cobas 4800 HPV test included fully automated sample preparation combined with real-time PCR technology and software that integrates the two modules. One-milliliter aliquots of thinprep fluid were transferred to 13-mL barcoded tubes provided by the manufacturer. The cobas 4800 HPV test was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Roche Molecular Systems, CA, USA). COBAS generates individual qualitative results for HPV 16, HPV 18 and a pool of other high risk HPV genotypes.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software version 22 package. Cramer’s V test was used to for correlation intensity between HPV genotypes in couples. This test showed distribution of categorical data in different groups in this study. The concordance analysis was based on the couples’ enrollment data. The proportion of couples who were concordant and discordant was calculated. A couple was classified as having “type-specific positive concordance” if the man and woman had ≥1 HPV genotype in common. A couple was classified as having “negative concordance” if both the man and woman were negative for 14 high risk genotypes. P value was considered significant when < 0.05.

Results

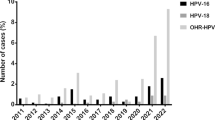

Out of 487 men referred to Nilou laboratory, 193 were single without a clear history of sextual partnership and hence excluded from the survey. Finally, 114 couples were eligible and were enrolled in this study (Fig. 1). Table 1 shows the demographic and details of HPV assay analysis of individuals. The mean age of participants were 36 ± 8 and 32 ± 7 for males and females, respectively without any significant association between genders among different age groups (Table 1). Considering the different age groups, in both genders, the highest prevalence was found between age group of 30 and 40 years old (48.6% of total population), however, with no significant associations (Table 1, Fig. 2, a and b). 64 (28%) of specimens were positive for at least one HPV genotype which were consisted of 35 (30.7%) and 29 (25.4%) for females and males, respectively (P value, 0.021, Table 1). 52 (81.2%) and 12 (18.8%) of positive samples were composed of single and multiple HPV genotypes respectively (P value 0.433, Table 1). Within the positive samples, 13(5.7%), 8 (7%) and 31(13.5%) were belonged to 16, 18 and other HR genotypes (Table 1). Between females, 6 (5.2%), 4 (3.5%) and 18 (15.7%) and among males, 7(6.1%), 4 (3.5%) and 13 (11.4%) were positive for 16, 18 and other HR genotypes, respectively (Table 1). Among genders, other HR genotypes than 16 and 18 prevalence were reached statistically significant (P value, 0.047, Table 1, Fig. 2, c).

Regarding the couples, they were classified into four groups. Groups I consisted of 59 (51.8%) couples who were negative for HPV,whereas, groups II, III and IV comprised the total positive HPV patients (55 couples, 48.2%) (Table 2). Among group II, all couples showed positive concordant, but only one husband showed partial concordance who had HPV-16 along with other HPV genotypes whereas his wife had only other types (Table 2, group II). Group III was composed of 20 couples (17.5%) in whom females were negative for HPV; however, their male partners were positive for at least one HPV genotype (Table 2). This group had five HPV-16, four HPV-18, two 16+ others and nine others HPV genotypes. Females who were positive, but their partners were negative for HPV were belonged to group IV, 26 couples (22.8%, Table 2). This group had four HPV-16, four HPV-18, three mixed 16 and 18, two 16+ others, one 18+ others and twelve others HPV genotypes. In total, of groups all groups studied, group I considered as being negative concordance; group II, positive concordance and groups III and IV showed neither kinds of concordance.The highest rate of HPV discordant results was observed for group IV (Table 2).

Discussion

HPV infection is very widespread among males and females across all geographical, racial and socio-economic populations worldwide and is the only sexually transmitted disease that is difficult to be handled in both members of a sexual couple. The substantial increased prevalence of genital tract HPV infections in many regions has been ascribed to an early start of sexual activity, poor sexual hygiene, multitude number of sexual partners, and insufficient preventive measures [19]. The objectives of the current investigation were to characterize the type-specific HPV genital infection positivity distribution and and to analyse their concordance in a group of stable heterosexual partners who referred to Nilou laboratory by gynecologists.

HPV genotypes prevalence and its concordance among heterosexual couples have been studied in many trials although with evident variations in the concordance. However, there are not too many reports on HPV concordance between referral subjects [20,21,22] (Table 3). General and type-specific HPV infection concordance in sexual partners have been assessed in these surveys with heterogeneous results which could be explained by the target populations, the DNA detection techniques and sampling methods-used (Table 3). Even two reports from the same countries (the USA and mexico) showed completely different results (Table 3). The range of type-specific HPV positive concordance is wide, ranging from as low as 16.6 to 59% (Table 3) suggesting that concordance is more variable than expected by chance. Present findings revealed that only 9 (16.3%) couples had positive concordance, which was showed the lowest rate among surveys on HPV compliance between referral couples outlined in Table 3. Our study along with Prada’s report from Mexico [20] showed the lowest proportion of positive concordance between couples (16.3% and 16.6%, respectively, Table 3).

There are almost no uniform findings between HPV genotypes concordance between sexual partners. They seem to depend upon the type of sexual relationship between male and female and the duration of relationship between couples, immune status differences between them and possibly other environmental factors [6, 13]. Immune responses may affect the viral load, the alternation of viral types, and therefore, discordance between partners with long-term relationships [1]. Moreover, the lack of concordance in a proportion of couples may be explained by differences in the time required for elimination of HPV infection in males and females.

The prevalence of HPV genotypes in couples differs among different surveys, reporting rates of 3.5 to 59% for HPV 16, from 3.5 to 6.7% for HPV 18, and from 3.5% to 8.5% for other HPV genotypes [3, 17, 23]. Types 16 and 18 are responsible for at least 70% of cervical cancer incidences and especially HPV 16 accounts for a large proportion of other cancers attributed to HPV in males and females. Moreover, types 16 and 18 appear to be more persistent than other HPV genotypes and therefore differences between viral genotypes in terms of clearance time may also influence concordance between couples [24,25,26,27,28].

Admittedly, there are some shortages for this study. Firstly, small sample size prevents generalization of results to the country. Secondly, we did not evaluate the existing risk factors due to unwillingness of participated partners. Evaluation of these factors associated with type-specific positive concordance in healthy heterosexual couples is necessary to increase our understanding of HPV acquisition and transmission dynamics [13]. Thirdly, no monitoring of the duration and clearance of the HPV infection among couples was carried out.

In conclusion, it is still important to investigate the HPV genotypes concordance between couples. Recognition of the dynamics of HPV infection not only in women, but in sexual partners could impact the implementation of preventive measures for cervical cancer and other HPV-related diseases. Protective measures like HPV vaccination in men will protect not only them but will also benefit their sexual partners. Therefore, policies to mitigate HPV infections in couples may give rise in public health improvement.

Availability of data and materials

Authors can confirm that all relevant data are included in the article and materials are available on request from the authors.

References

de Lima Rocha MG, Faria FL, Goncalves L, Souza Mdo C, Fernandes PA, Fernandes AP. Prevalence of DNA-HPV in male sexual partners of HPV-infected women and concordance of viral types in infected couples. PLoS One. 2012;7:e40988.

Daling JR, Madeleine MM, Johnson LG, Schwartz SM, Shera KA, Wurscher MA, et al. Penile cancer: importance of circumcision, human papillomavirus and smoking in in situ and invasive disease. International journal of cancer Journal international du cancer. 2005;116:606–16.

Franceschi S, Castellsague X, Dal Maso L, Smith JS, Plummer M, Ngelangel C, et al. Prevalence and determinants of human papillomavirus genital infection in men. Br J Cancer. 2002;86:705–11.

Giuliano AR, Tortolero-Luna G, Ferrer E, Burchell AN, de Sanjose S, Kjaer SK, et al. Epidemiology of human papillomavirus infection in men, cancers other than cervical and benign conditions. Vaccine. 2008;26(Suppl 10):K17–28.

Dunne EF, Nielson CM, Stone KM, Markowitz LE, Giuliano AR. Prevalence of HPV infection among men: a systematic review of the literature. J Infect Dis. 2006;194:1044–57.

Partridge JM, Koutsky LA. Genital human papillomavirus infection in men. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6:21–31.

Munoz N, Bosch FX. The causal link between HPV and cervical cancer and its implications for prevention of cervical cancer. Bull Pan Am Health Organ. 1996;30:362–77.

Munoz N, Bosch FX, de Sanjose S, Tafur L, Izarzugaza I, Gili M, et al. The causal link between human papillomavirus and invasive cervical cancer: a population-based case-control study in Colombia and Spain. International journal of cancer Journal international du cance1992. 52:743–9.

Chaturvedi AK, Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, Hernandez BY, Xiao W, Kim E, et al. Human papillomavirus and rising oropharyngeal cancer incidence in the United States. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29:4294–301.

Jin F, Stein AN, Conway EL, Regan DG, Law M, Brotherton JM, et al. Trends in anal cancer in Australia, 1982-2005. Vaccine. 2011;29:2322–7.

Tota JE, Chevarie-Davis M, Richardson LA, Devries M, Franco EL. Epidemiology and burden of HPV infection and related diseases: implications for prevention strategies. Prev Med. 2011;53(Suppl 1):S12–21.

Plaut A, Kohn-Speyer AC. The carcinogenic action of Smegma. Science. 1947;105:391–2.

Burchell AN, Tellier PP, Hanley J, Coutlee F, Franco EL. Human papillomavirus infections among couples in new sexual relationships. Epidemiology. 2010;21:31–7.

Hernandez BY, Wilkens LR, Zhu X, Thompson P, McDuffie K, Shvetsov YB, et al. Transmission of human papillomavirus in heterosexual couples. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:888–94.

Bleeker MC, Berkhof J, Hogewoning CJ, Voorhorst FJ, van den Brule AJ, Starink TM, et al. HPV type concordance in sexual couples determines the effect of condoms on regression of flat penile lesions. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:1388–92.

Nicolau SM, Camargo CG, Stavale JN, Castelo A, Dores GB, Lorincz A, et al. Human papillomavirus DNA detection in male sexual partners of women with genital human papillomavirus infection. Urology. 2005;65:251–5.

Rombaldi RL, Serafini EP, Villa LL, Vanni AC, Barea F, Frassini R, et al. Infection with human papillomaviruses of sexual partners of women having cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Brazilian journal of medical and biological research = Revista brasileira de pesquisas medicas e biologicas / Sociedade Brasileira de Biofisica [et al]. 2006;39:177–87.

Rosenblatt C, Lucon AM, Pereyra EA, Pinotti JA, Arap S, Ruiz CA. HPV prevalence among partners of women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. International journal of gynaecology and obstetrics: the official organ of the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 2004;84:156–61.

Schmauz R, Okong P, de Villiers EM, Dennin R, Brade L, Lwanga SK, et al. Multiple infections in cases of cervical cancer from a high-incidence area in tropical Africa. International journal of cancer Journal international du cancer. 1989;43:805–9.

Parada R, Morales R, Giuliano AR, Cruz A, Castellsague X, Lazcano-Ponce E. Prevalence, concordance and determinants of human papillomavirus infection among heterosexual partners in a rural region in Central Mexico. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:223.

Nyitray AG, Menezes L, Lu B, Lin HY, Smith D, Abrahamsen M, et al. Genital human papillomavirus (HPV) concordance in heterosexual couples. J Infect Dis. 2012;206:202–11.

Widdice LE, Breland DJ, Jonte J, Farhat S, Ma Y, Leonard AC, et al. Human papillomavirus concordance in heterosexual couples. The Journal of adolescent health : official publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. 2010;47:151–9.

Vargas H, Betancourt J, Sierra Y, Gómez S, Diaz L, Laboratorio de Salud Pública SJ. Subsecretaria de salud pública La Plata, Argentina. Mol Biol. 2016;5(3).

Hernandez-Sotelo D, Ortiz J. HPV in men and concordance of viral types in infected couples in southern Mexico. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2016;9:2106–12.

Reiter PL, Pendergraft WF 3rd, Brewer NT. Meta-analysis of human papillomavirus infection concordance. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 2010;19:2916–31.

Bleeker MC, Hogewoning CJ, Berkhof J, Voorhorst FJ, Hesselink AT, van Diemen PM, et al. Concordance of specific human papillomavirus types in sex partners is more prevalent than would be expected by chance and is associated with increased viral loads. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2005;41:612–20.

Bleeker MC, Hogewoning CJ, Voorhorst FJ, van den Brule AJ, Berkhof J, Hesselink AT, et al. HPV-associated flat penile lesions in men of a non-STD hospital population: less frequent and smaller in size than in male sexual partners of women with CIN. International journal of cancer Journal international du cancer. 2005;113:36–41.

Ramanakumar AV, Goncalves O, Richardson H, Tellier P, Ferencz A, Coutlee F, etal. Humanpapilomavirus (HPV)types16,18,31,45DNAloadsnadHPV16integrationin persistent and transient infections in youngwomen. BMC Infect Dis2010;10:326.

Acknowledgments

We thank Nasim Siadati, and Saeed Delshad from Nilou medical laboratory for the data and sample handling, interviewing with the patients and technical supports.

Funding

This work was supported by nilou medical laboratory in Tehran.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MD and SJ carried out the HPV studies, contributed towards the study design and wrote the manuscript. MD contributed towards HPV test by COBAS® and performed the statistical analysis, MG and M Dezfulian assisted in the development of the concepts, SY,MT and PS conducted the necessary for testing in a laboratory and a consultancy for study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the National Ethics Committee for Biomedical Research affiliated to The Ministry of Health and Medical Education in Tehran. Ethic code is IR.IAU.K.REC.1396.10. A written informed consent guaranteeing confidentiality was taken from each patient.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Davarmanesh, M., Dezfulian, M., Gharavi, M. et al. Human papilloma virus (HPV) genotypes concordance between Iranian couples referrals. Infect Agents Cancer 14, 22 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13027-019-0241-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13027-019-0241-x