Abstract

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) are two fatal neurodegenerative disorders with considerable clinical, pathological and genetic overlap. Both disorders are characterized by the accumulation of pathological protein aggregates that contain a number of proteins, most notably TAR DNA binding protein 43 kDa (TDP-43). Surprisingly, recent clinical studies suggest that dyslipidemia, high body mass index, and type 2 diabetes mellitus are associated with better clinical outcomes in ALS. Moreover, ALS and FTLD patients have a significantly lower incidence of cardiovascular disease, supporting the idea that an unfavorable metabolic profile may be beneficial in ALS and FTLD. The two most widely studied ALS/FTLD models, super-oxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) and TAR DNA binding protein of 43 kDA (TDP-43), reveal metabolic dysfunction and a positive effect of metabolic strategies on disease onset and/or progression. In addition, molecular studies reveal a role for ALS/FTLD-associated proteins in the regulation of cellular and whole-body metabolism. Here, we systematically evaluate these observations and discuss how changes in cellular glucose/lipid metabolism may result in abnormal protein aggregations in ALS and FTLD, which may have important implications for new treatment strategies for ALS/FTLD and possibly other neurodegenerative conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a fatal neurodegenerative disorder that is characterized by the progressive degeneration of both upper and lower motor neurons, which results in a multitude of motor symptoms, including muscle weakness, fasciculations, spasticity, dysphagia, and eventually respiratory dysfunction [167]. There is also an established clinical overlap between ALS and frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD). FTLD is a pathological diagnosis that manifests clinically in the form of frontotemporal dementia (FTD), which is characterized by cognitive, behavioral, and linguistic dysfunction. Almost 50% of ALS patients show cognitive impairment of the type observed in FTD, with 15% of ALS cases meeting diagnostic criteria for FTD at the time ALS is diagnosed [144]. In addition, 15% of FTLD cases have clinically detectable motor symptoms [92]. Ten percent of all ALS patients, and one third of all FTLD patients, have a positive family history with at least one immediate family member having the disease [92, 119]. The prevalence (62%) and pattern (related to FTD) of cognitive impairment in familial ALS are similar to that of sporadic ALS [183].

Like many neurodegenerative diseases, ALS and FTLD are associated with the abnormal aggregation of specific proteins in neurons and glia. Superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) was the first aggregated protein to be associated with ALS, just over two decades ago [147]. Since then, several other proteins have been shown to form abnormal neuronal aggregates in ALS and FTLD, including TAR DNA binding protein 43 kDa (TDP-43) and fused in sarcoma (FUS). According to the predominant type of aggregated protein found, ALS is classified as ALS-TDP, ALS-FUS, or ALS-SOD; and FTLD as FTLD-Tau, FTLD-TDP, FTLD-FUS, or FTLD-UPS (for Ubiquitin-Proteasome system) [102]. Among these subtypes, ALS-TDP and FTLD-TDP are the most common, representing 98% of ALS and 45% of FTLD cases, and are the most important indicator that there is a pathophysiological continuum between the two disorders [92].

The molecular mechanisms that underlie abnormal neuronal protein aggregation in ALS/FTLD remain unknown, but mutations in several genes can trigger the formation of such aggregates. TDP-43 aggregates result from mutations in the TARDBP gene, as well as from mutations in progranulin (PGRN), chromosome 9 open reading frame 72 (C9ORF72), valosin-containing protein (VCP), p62/sequestosome (SQSTM1), optineurin (OPTN), chromatin modifying protein 2B (CHMP2B), and Ubiquilin 2 (UBQLN2). Similarly, FUS protein aggregates result from mutations in the FUS gene, as well as in TATA-binding protein-associated factor 15 (TAF15), and Ewing’s sarcoma breakpoint region 1 (EWSR1) [101]. Notably, abnormal aggregates are present in all ALS/FTLD cases even when no genetic mutations are present. As discussed later, the causes of neuronal death in ALS/FTLD are also unknown and are being investigated in animal models, with studies supporting a role for oxidative damage, excitotoxicity, and apoptosis [46, 110, 132, 170].

Clinical and epidemiological studies have identified a number of risk factors and disease-modifiers that can impact the clinical course in ALS and FTLD, including metabolic parameters. Notably, a conventionally ‘risky’ cardiovascular profile, such as a high body mass index (BMI), or diabetes mellitus type 2, might protect individuals from ALS by delaying the onset of symptoms and/ or slowing clinical progression, whereas, a ‘beneficial’ cardiovascular profile, with a low body mass index, an athletic lifestyle, and low blood cholesterol levels, may increase the risk or worsen the prognosis [77]. This intriguing relationship between metabolism, ALS and FTLD warrants a thorough evaluation of the rapidly accumulating clinical evidence on the topic, as well as, exploration of molecular data that could reveal their biological underpinnings and suggest new treatment strategies.

In this review, we discuss the disease-modifying effects of metabolic disorders in ALS/FTLD and the preclinical studies that demonstrate the involvement of ALS- and FTLD-associated genes/proteins in metabolic pathways. Moreover, we present several hypotheses as to how metabolic perturbations may modulate pathological protein aggregation or its consequences in ALS and FTLD. We conclude by discussing a potential disease-modifying effect of metabolic disorders in other neurodegenerative disorders.

The disease-modifying effects of metabolic disorders in ALS

Table 1 summarizes studies suggesting a protective role for traditionally “risky” cardiovascular profiles in ALS and FTLD.

Dyslipidemia

Dyslipidemia appears to be protective in ALS, both in terms of improved prognosis and reduced risk of the disease. An abnormally high low-density lipoprotein (LDL)/high-density lipoprotein (HDL) ratio is associated with an increase in survival by 12 months in ALS [n = 369, [47]]. Similarly, triglycerides above 1.47 mmol/L prolong survival in ALS patients by 14 months [n = 488, [44]]. Furthermore, antecedent hyperlipidemia delays ALS onset [n = 1439, [67]]. This association is further supported by studies demonstrating that a conventionally ‘favorable’ vascular profile, including hypolipidemia, increase the risk of ALS. Sometimes, this in a gender-dependent fashion with only male ALS patients having significantly lower total cholesterol and triglycerides than male controls [166, 191].

The effect of dyslipidemia on ALS survival could be confounded by other factors, such as body mass index [BMI, [124]]. Rafiq et al. showed a beneficial effect of dyslipidemia on survival in a cohort of ALS patients (n = 512) enrolled in the Olesoxime (a neuroprotective compound) phase II-III clinical trial for ALS treatment; however, the statistical significance was lost when adjusted for age of onset, or BMI [140]. Similarly, Dedic et al. observed an approximately 8 month longer survival in ALS patients (n = 82) who have dyslipidemia compared to those without dyslipidemia, but it was not statistically significant [35]. Both studies, however, included a remarkably higher proportion of ALS patient with dyslipidemia (64% in Rafiq et al. and 52% in Dedic et al.) than has been reported for other ALS cohorts (around 40% in Hollinger et al.), raising a question about the generalizability of these results.

Diabetes mellitus

Some earlier reports suggested that ALS patients might have certain features of diabetes mellitus (DM), such as glucose intolerance [143]. More recent studies have shown a considerate influence of diabetes mellitus on ALS risk and prognosis. Insulin-dependent Type 1 DM (T1DM) appears to increase the risk of ALS 5.83 times (OR: 1.87–15.51, [105]). In stark contrast, however, Type 2 DM (T2DM), a form of insulin-independent DM, appears to have a beneficial effect on the course of ALS in terms of a reduced risk and better prognosis [74, 77]. A likely explanation for contrasting effects of T1DM and T2DM on ALS could be the different etiopathogenesis of the diseases. In contrast to TD2M, T1DM is an autoimmune disorder, and they are known to increase the risk of ALS [171].

A Swedish ALS cohort (n = 5108) showed an inverse association (OR: 0.66, 95% CI 0.53–0.81) between non-insulin dependent DM (likely T2DM) and the risk of ALS [105]. Two different American cohorts have also reported a reduced prevalence of T2DM in ALS patients, suggesting that T2DM might reduce the risk of ALS [111, 125]. In our large study of 2371 patients, pre-morbid T2DM, i.e., occurring before onset of ALS symptoms, was associated with a four-year delay in ALS onset and a prolonged survival of about six months [75]. Another study showed a trend (p < 0.1) towards slower disease progression in ALS patients with pre-morbid T2DM [74, 125]. Finally, a recent study investigated for ALS occurrence in all residents of Turin (n = 727,977) who were 14 years of age at 1996 during an assessment period from 1998 to 2014. During this period, 397 patients developed ALS and diabetes was found to decrease the risk (hazard ratio: 0.30, 95% CI 0.19–0.45) of ALS occurrence [32]. A Taiwanese study, however, did not show a link between T2DM and ALS [165]. Similarly, an assessment of the association with baseline HbA1c and survival in Chinese ALS patients (n = 450) showed that increased baseline HbA1c was associated with increased risk of mortality [182]. These discrepant results in Asian ALS patients raise the possibility that the protective effect of T2DM on ALS could depend on ethnicity [97].

Body weight

The association between body weight and ALS is very interesting. Several studies have shown that a low (under-weight) pre-morbid body mass index (BMI) is a risk factor for ALS ([72, 104, 116, 122]). At the other end of the spectrum, several studies have shown that a high (over-weight or obese) BMI at diagnosis is associated with slower disease progression and decreased mortality in ALS [56, 141]. In another ALS cohort (n = 285), the rate of symptom progression was inversely related to changes in BMI during the first year after ALS diagnosis [76]. Other studies have also demonstrated that a decrease in BMI after onset of motor symptoms dramatically reduces survival in ALS patients [125, 157]. Collectively, these studies strongly suggest an association between lower body weight and ALS risk, and a worse prognosis in patients with faster weight loss after ALS diagnosis.

Physical activity

Physical activity is an important determinant of metabolic homeostasis and hence may be very relevant to ALS risk. Several studies, in fact, report that high levels of physical activity and/or an athletic lifestyle significantly increase the risk and/or worsen the prognosis of ALS [11, 25, 72, 98, 123, 169]. However, not all studies have come to this conclusion [173, 177], and one study suggests that exercise and high levels of physical activity may even be beneficial, with overall physical activity associated with a reduced odds (OR = 0.56, 95% CI: 0.36–0.87) of having ALS [138].

It is possible that this wide variability in outcomes is related to the fact that almost all of these studies have been retrospective. A recent Cochrane systematic review on the role of exercise on ALS risk and progression identified a lack of comparable outcome parameters in retrospective studies, as well as a lack of prospective analyses as likely reasons for these conflicting results [33]. The first prospective study (n = 472,100) reported a borderline significantly (p = 0.042) decreased risk of dying (HR = 0.67, 95% CI: 0.42–1.06) from ALS in patients with high levels of physical exercise at the time of enrollment [55]. However, a robust case-control study of ALS patients (n = 1557) vs. matched controls (n = 2992) recruited from five population-based registries in The Netherlands, Ireland, and Italy revealed a modest linear association between physical activity and ALS risk ((OR: 1.06, p < 0.001), [179]). More prospective analyses in future will likely clarify the association between exercise and ALS.

Metabolic drugs

Clinical studies suggest that there is an intriguing relationship between the use of drugs that treat common metabolic conditions and the risk and rate of progression of ALS.

Despite rapidly emerging evidence that T2DM is protective in ALS, certain anti-diabetic drugs have been used to treat ALS because of their anti-inflammatory properties. Pioglitazone, which is used to manage T2DM, enhanced the survival of a mouse SOD1 model of ALS; however, a phase II clinical trial suggested that this drug increased the risk of death in ALS patients, although this increase lacked statistical significance [48, 77]). Collectively, the results of these studies suggest caution in use of drugs that are used to treat T2DM and dyslipidemia in ALS patients.

Preliminary reports have suggested an increased occurrence of ALS among users of statins, which are used to treat dyslipidemia [50]. However, more rigorous analyses have subsequently found a null association between statins and ALS risk (OR: 0.96, 95% CI: 0.73–1.28, [158]), as well as, prognosis [45]. Similarly, other reports suggest that the association between statin use and risk of ALS could be gender-dependent, with only female ALS patients on statins showing a significantly faster decline (a decline of 3 points more over 12 months) in (ALS-functional rating scale) ALS-FRS compared to those not on statins [118].

Diet-based trials for ALS treatment

The evidence that changes in BMI and metabolic perturbations can alter the course of ALS has led to several trials of diet-based treatment for this disease. A notable example is a prospective interventional study (n = 26) that compared a high-fat and high-carbohydrate diet in ALS, which showed that both diets could stabilize or increase the BMI of ALS patients [43]. However, this study did not explore the effects of a stabilized BMI on disease progression or survival. In another placebo-controlled, phase II trial (n = 26), mortality and disease progression in ALS patients on a high calorie/high carbohydrate (HC/HC) diet or on a high-calorie/high-fat (HC/HF) diet was compared to mortality and disease progression in ALS patients on a normal control diet. This trial found significantly (p < 0.03) reduced mortality (p < 0.03) and a trend towards slower ALS progression (p = 0.07), in the HC/HC group versus controls [185].

Other studies also suggest beneficial effects (slower progression and/ or longer survival) of nutritional counseling [6], and of diets that contain omega-3 fatty acids [53], anti-oxidants and carotenes [78, 121], acetyl carnitine [12], and Vitamin E [54] in ALS. The role of Vitamin D, however, remains unclear, with both its deficiency [20, 82] and increased levels (-[15]) having been associated with worse prognosis in ALS.

In conclusion, current evidence strongly supports a role for dyslipidemia, T2DM, and obesity in reducing the risk for acquiring ALS and improving its prognosis. A recent study further showed an inverse association between serum retinol binding protein-4 and ALS risk and prognosis. Serum retinol binding protein 4 indicates the overlapping molecular manisfestaion of insulin resistance in dyslipidemia/T2DM/obesity, and thus provides further evidence for a protective effect of metabolic disorders in ALS [148]. The evidence supporting a disease-modifying effect of exercise and dietary regimens on ALS is, however, less conclusive and warrants further investigations. There is also evidence for a disease-modifying role of metabolic disorders on the risk and prognosis of the closely related disorder, FTLD.

The disease-modifying effect of metabolic disorders in FTLD

The disease-modifying effects of metabolic disorders in FTLD have not been well studied. However, in a large cohort of military veterans with dementia (n = 554), the risk of developing FTD was reduced (OR = 0.4, CI = 0.3–0.96) in patients with cardiovascular disease [80]. A study of 31 behavioral variant FTD patients and 19 controls found that behavioral FTD patients have considerably higher (1.9 mmol/L) serum triglycerides than controls (0.85 mmol/L), which is a known cardiovascular risk factor [3].

More studies are thus needed to ascertain whether metabolic disorders have a protective effect on the progression of FTLD, similar to their effect on ALS. It is also plausible that metabolic perturbations have contrasting effects on the motor and cognitive functioning of the brain. We found, for example, that T2DM has contrasting effects on the motor and cognitive functions of patients with ALS. Pre-morbid T2DM delayed the onset of motor symptoms in ALS patients, but impaired frontal and temporal cognitive functioning [75]. Animal models and neuropathological studies will certainly help delineate these effects.

Evidence for metabolic dysfunction in ALS/ FTLD through omics and biochemical assays

Mass-spectrometry based omics approaches present a great opportunity for a wide-scale and robust investigation of a pathophysiological link between neurodegenerative and metabolic processes in ALS/ FTLD. An initial metabolomics-based comparison between ALS patients (n = 19) and controls (n = 33) found an increase in 6 metabolites in the plasma of ALS patients, however the study did not indicate their exact characteristics [149]. Another study showed an increase in 23 metabolites, notably related to hypermetabolism, oxidative damage, and mitochondrial dysfunction in the plasma of ALS patients (n = 62 + 99 for two different assessments) compared to controls (n = 69 + 48 for two different assessments) [86]. Importantly, a number of these metabolites, such as Carnitine and Paraxanthine are also altered in T2DM and dyslipidemia, in the opposite direction [13, 172]. A third study demonstrated changes in plasma tryptophan, arginine, and proline metabolism pathways in the plasma of ALS patients (n = 24) relative to age- and gender-matched controls (n = 24) [134]. Intriguingly, some of these metabolites, such as Valine and Serine, again show an opposite expression in dyslipidemia and T2DM [22, 113, 189]. More recent lipidomics analyses further reveal hypoalphalipoproteinemia and increased CSF phosphatidylcholine as metabolic signatures of bvFTD [84] and ALS [16] respectively.

In addition to metabolomics, other biochemical analyses have also revealed peripheral metabolic signatures unique to ALS. A study on peripheral lipoproteins revealed a characteristic low IDL-B and high LDL-1 in the serum of ALS patients [37]. Another study, which quantified 40 different sterols, showed that (25R) 26-hydroxycholesterol, the immediate precursor of 3β-hydroxycholest-5-en-26-oic acid, was reduced in ALS patients compared with controls [2]. These analyses are very important additions to the aforementioned clinical observations showing the effect of metabolic disorders on ALS/ FTLD.

Metabolic dysfunction in animal models of ALS/FTLD

Another important approach to understanding and utilizing metabolic changes in ASL/FTD are animal models where one can control for many variables that are challenging in humans.

SOD1 and TDP-43 are the most widely studied animal models of ALS/FTLD, and there are several important recent studies manipulating SOD1 and TDP-43 genes (knock-out, conditional knock-out, knock-in, over-expression of the endogenous or human protein, mutations) to decipher metabolic changes in these animals and utilizing these findings for pre-clinical trials of metabolism-based therapeutic strategies.

Metabolic dysfunction in the SOD1 model of ALS

Missense mutations in the Cu/Zn-binding superoxide dismutase (SOD1) gene, which encodes a ubiquitously expressed antioxidant enzyme, are reported in 10–20% cases of familial ALS [38, 147]. Sod1 mutant mice develop many pathological features of human ALS, including loss of upper and lower motor neurons, progressive paralysis, and the accumulation of ubiquitinated inclusions in the neurons that contain misfolded Sod1 [59, 145].

SOD1 mice also exhibit signs of metabolic dysfunction, including increased energy expenditures, skeletal muscle hypermetabolism, and reduced adipose tissue, even at the asymptomatic stage [49, 127]. This is followed by rapid weight loss after symptom onset [62]. Furthermore, Sod1 mutant mice also exhibit wide-ranging deregulation of their lipid metabolism, including peripheral hypolipidemia [41, 52, 83] and upregulated levels of ceramides, glucosylceramides and glycosphingolipids [42, 64, 155].

The metabolic perturbations observed in Sod1 mutant mice have prompted scientists to explore their therapeutic potential. The administration of a high-fat, energy-rich diet protected Sod1 mouse mutants against motor disease progression [49, 52]. Similarly mitigating effects have been reported following the treatment of Sod1 mouse mutants with the triglyceride triheptanoin [168] or with a ganglioside, GM3 [42]. Switching mutant Sod1 mice from a normal to a ketogenic diet, or giving them caprylic triglyceride, which is metabolized to ketone bodies, restored their mitochondrial ATP production and was accompanied by reduced neuronal loss, delayed onset of motor dysfunction, and enhanced survival [193, 194]. Arginine-alpha- ketoglutarate supplementation also improved the motor functions and lifespan of Sod1 mutant mice [7]. In contrast, caloric restriction in rodent models expressing mutant Sod1, have shown detrimental effects, i.e. earlier symptom onset and shortened lifespan [60, 61, 133].

Metabolic dysfunction in TDP-43 models

The presence of ubiquitinated and phosphorylated cytoplasmic inclusions of TDP-43 in the CNS of patients with ALS and FTLD [119], and the subsequent identification of TARDBP mutations in the sporadic and familial forms of these diseases [57, 79, 160, 175, 192], have led to the rapid development of TDP-43 transgenic models. Mutant Tardbp mice manifest some key features of human ALS and FTLD, including motor neuron loss, gliosis, motor and cognitive deficits, and early mortality [4, 5, 8, 18, 73, 162, 186, 188, 194].

As with the SOD-1 mutants, the TDP-43 rodent models have demonstrated metabolic dysfunction. The conditional neuromuscular knock-out [24, 190] of Tardbp in mice led to a reduction in adipose tissue and weight loss [24, 164]. This effect was mediated by depletion of the protein Tbc1 domain family member 1 (Tbc1d1), which regulates the translocation of glucose 4 transporter (GLUT4) and energy homeostasis (reviewed in [152]) in skeletal muscles, and which favored lipolysis and leanness. Conversely, TDP-43 overexpression lead to elevated Tbc1d1 in skeletal muscle, which was associated with an increase in body fat and defective insulin-mediated glucose uptake [161].

A recent study in TDP-43 mutant mice demonstrated the beneficial effects of an energy-rich, high-fat jelly diet in enhancing survival [29]. This was corroborated by the protective effects of high sugar intake in a Caenorhabditis elegans model of ALS that expresses mutant TDP-43 [1]. Similarly, supplementation with medium-chain fatty acids and beta-hydroxy butyric acid, as well as genetic manipulation of the carnitine shuttle, which is important to mitochondrial transport of long-chain fatty acids, improves motor functions in a drosophila model of ALS with mutant TDP-43 over-expression [103].

Collectively, evidence from Sod1 and TDP-43 models reveals a potential for metabolic, therapeutic intervention strategies in ALS/FTLD. The next section addresses the critical question of whether and how ALS/FTLD proteins modify metabolism.

Role of ALS/FTLD-associated proteins in metabolism

ALS/FTLD associated proteins may act directly to regulate cellular and/or whole-body metabolism, which we review here and in Table 2.

The TDP-43 protein

As noted, TDP-43 can regulate whole-body metabolism and glucose transport through the obesity-related gene Tbc1d1 [24, 161]. It is now known that the TARDBP knock-in mice have increased serum levels of free fatty acids and HDL cholesterol. This phenotype is accompanied by decreased expression of the gene encoding the fatty acid transporter, CD36, and by the dysregulation of a cluster of genes involved in energy production, lipid metabolism, the respiratory electron transport chain and various mitochondrial pathways [164].

In vitro, TARDBP regulates glycolysis in a hepatocellular carcinoma cell line through the miRNA-mediated post-transcriptional regulation of a key rate-limiting glycolytic enzyme phosphofructokinase (PFKP) [131]. These studies highlight an important role for TDP-43 in the regulation of key metabolic processes, including glucose and lipid transport and metabolism, and provide a basis for the observed disease-modifying effect of metabolic dysfunction in ALS and FTLD.

Progranulin

Haploinsufficient, loss-of-function mutations in the human PGRN gene are found in 5–20% of patients with familial FTLD and are a common cause of FTLD-TDP ([9, 30, 100]. Progranulin (PGRN) is an ~ 70 kDa, secreted protein that is implicated in numerous cellular processes, from inflammation to wound healing [63, 187]. In the brain, PGRN is believed to function as a neurotrophic factor [150, 174].

Now, PGRN is known to have an important role in lipid metabolism and insulin signaling. In contrast to its pathogenic role in FTLD, Pgrn haploinsufficiency in mice confers protection against diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance [120]. Conversely, higher plasma levels of PGRN have been found in patients with T2DM, which is characterized by insulin resistance [139]. Similarly, insulin resistance, adipocyte hypertrophy and obesity result from perturbations in the regulation of the inflammatory cytokines interleukin 6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) in mice with increased PGRN through Pgrn over-expression or administration of recombinant PGRN [93, 95, 107, 196]. Furthermore, the administration of recombinant PGRN to wild type mice leads to impaired insulin sensitivity [93, 95]. Trehalose, a natural disaccharide, has also been proposed as a possible therapy for FTLD as it can restore wild type levels of progranulin expression in Prgn haploinsufficient mice [66]. Taken together, these studies suggest that PGRN lies at the intriguing interface between metabolic disorders and ALS/FTLD, whereby its deficiency is associated with neurodegeneration and its increase is associated with metabolic perturbations.

The TREM2 protein

A missense variant of triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 (TREM2) (p.R47H) was recently shown to increase the risk of multiple NDDs, including Alzheimer’s disease and ALS in genome-wide association studies (GWAS). TREM2 is also associated with a poorer ALS prognosis as higher spinal cord levels of TREM2 protein in ALS patients correlate with reduced survival [19]. TREM2 is a 26 kDa transmembrane glycoprotein that is involved in multiple inflammatory processes, including microglia activation [195].

Recent animal studies have revealed that TREM2 can regulate adipogenesis by inhibiting the Wnt10b/β-catenin signaling pathway. This action stimulates adipogenesis by increasing the glycogen synthase kinase-3β-mediated phosphorylation of β-catenin, and by increasing adipocyte differentiation through upregulation of the adipogenic transcription factors CCAAT-enhancer binding protein alpha (C/EBPα) and peroxisome proliferative-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) [128, 129]. Accordingly, Trem2 over-expressing mice exhibit insulin resistance, adipocyte hypertrophy, and hepatic steatosis [130]. Similarly to PGRN and TDP-43, the metabolic functions of TREM2 seem to contribute to ALS: TREM2 deficiency is deleterious in ALS, whereas TREM2 over-expression leads to various features of metabolic syndrome that have been shown to be favorable in ALS.

FET proteins

A family of RNA-binding proteins, called the FET proteins (as the family members include FUS, EWS, and TAF15), is important for RNA metabolism. They form abnormal aggregates in ALS/ FTLD similar to TDP-43 [81, 126, 197]. TAF15 and EWS often co-aggregate with FUS in the neurons and glia in most cases of FTLD-FUS but not in ALS with FUS mutations [101].

As with other FTLD proteins, FUS and EWS may also influence metabolic processes. An analysis of the FUS interactome by mass spectrometry showed that mutant FUS has an increased association with enzymes involved in glucose metabolism, compared to wild-type FUS [180]. Additionally, the over-expression of FUS has been reported to significantly reduce ATP levels in human neuroblastoma cells [180]. In HEK293 cells, the accumulation of FUS protein upon FUS over-expression reportedly limits Ca2+ availability in mitochondria, which is essential for several enzymes of the TCA cycle [58], resulting in decreased production of ATP [163]. In another study, mislocalization of FUS to the mitochondria induced mitochondrial fragmentation in FUS-overexpressing Drosophila melanogaster [39], which explained the impaired mitochondrial bioenergetics observed in these flies.

A similar decrease in mitochondrial density is seen in mouse preadipocytes that are deficient for EWS. Moreover, a host of genes involved in mitochondrial respiration and fatty acid β-oxidation were shown to be down-regulated in the liver of EWS knock-out mice [128, 129]. Similarly, EWS has been shown to regulate important metabolism-linked signaling pathways, such as Transforming growth factor- beta (TGF-β) and Insulin-like growth factor- 1 receptor (IGF-1R) [26, 65, 109, 136]. Taken together, these studies suggest that FET proteins, as with TDP43, are involved in energy homeostasis. This hypothesis, however, needs further investigation, especially in vivo.

The C9ORF72 protein

The discovery of mutations in the chromosome 9 open reading frame 72 (C9orf72) gene provided the first genetic and pathogenic link between ALS and FTLD [36, 142]. These mutations result in intronic GGGGCC hexanucleotide repeat expansions, and are present in almost 40% of familial and 10% of sporadic ALS cases characterized by TDP-43 pathology [92]. An exon-array analysis showed that C9orf72 repeat expansions lead to the differentially regulated splicing of several genes involved in cholesterol biosynthesis and glucose metabolism [27]. Recently, C9orf72-based ALS/FTLD rodent models have been generated [94], and it will be interesting to investigate whether alterations in glucose and cholesterol metabolism are associated, in these models, with disease severity.

Does metabolic dysfunction affect protein aggregation in ALS and FTLD?

Both clinical and basic research, then, suggest the involvement of metabolic processes in ALS/FTLD pathophysiology. An vital question to address is whether the abnormal protein aggregation in ALS and FTLD occurs as a consequence of changes in metabolism or vice versa. Here we propose three plausible pathways by which changes in cellular or whole-body metabolism may lead to protein aggregation in ALS and FTLD (Fig. 1).

-

1.

Physiological stress granules have been proposed to act as precursors of abnormal TDP-43 and FUS inclusions in ALS/FTLD [135], supported by the observation that stress granule components co-aggregate with TDP-43 and FUS [14]. Because the formation of stress granules might be induced by glucose deprivation [17], it is conceivable that factors that lead to glucose starvation, such as high-intensity exercise or caloric restriction, might predispose to stress granule formation and subsequently to TDP-43/FUS aggregation in ALS and FTLD. Conversely, T2DM and dyslipidemia might provide protection by supplying more glucose or alternate sources of energy, thereby preventing the formation of stress granules.

-

2.

Changes in the cellular metabolic environment may alter nucleocytoplasmic transport [69], leading to increased localization of TDP-43 or FUS to the cytoplasm, which is a prerequisite step in the formation of their cytoplasmic inclusions. Furthermore, glucose or lipid starvation can lead to activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), a major cellular energy sensor, which is found to be active in motor neurons of ALS patients and its activity correlates to the cytoplasmic mislocalization of TDP-43. Consistently, it has been shown that activation of AMPK induces cytoplasmic mislocalization of TDP-43 in motor neuronal cell lines [93, 95]. Rapidly accumulating evidence shows both T2DM and dyslipidemia are associated with reduction in AMPK activity, which was shown to be protective in genetic models of ALS [28, 91].

-

3.

Finally, prolonged caloric/energy restriction induces autophagy in cells [114] might, in turn, enhance protein aggregation. This is supported by the observation that autophagosome markers, such as microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3 (LC3), were present adjacent to TDP-43 inclusions in autopsies from ALS patients [51]. On the contrary, recent evidence suggests that autophagy is reduced in obesity and T2DM. Under diabetic conditions, activation of transforming growth factor beta and miR-192 reduce autophagy in renal glomerular cells [40]. Similarly, high fat diet induced dyslipidemia is known to impair lysosomal functioning and autophagy [195]. Therefore, it is likely that these conditions counteract the formation of autophagosomes, which serve as precursors to pathological aggregates in ALS/FTLD.

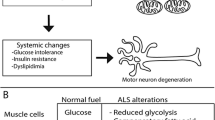

A model of how metabolic processes might contribute to abnormal TDP-43 aggregation in ALS/FTD. TDP-43 is primarily a nuclear protein that mislocalizes to the cytoplasm of neurons in pathological conditions, such as ALS/ FTD, where it undergoes phosphorylation and ubiquitination and forms cytoplasmic aggregates. Glucose starvation might contribute to the formation of TDP-43 aggregates by inducing the formation of stress granules. These stress granules might serve as precursors to TDP-43 inclusions. Similarly, caloric restriction might contribute to TDP-43 aggregation by triggering auto-phagosomes formation, which might serve as another site for TDP-43 aggregation

Does altered metabolism counteract effects of protein aggregation in ALS/FTLD?

An alternate possibility is that the abnormal protein aggregation in ALS and FTLD causes neurons to become unusually sensitive to metabolic deprivation, in a way that renders metabolic perturbations, such as dyslipidemia and T2DM, beneficial (Fig. 2). There are three major ways in which this could occur:

-

1.

TDP-43, and other proteins that aggregate in ALS and FTLD, could be potent regulators of core cellular metabolic processes. As such, their loss of function through aggregation might lead to a state of cellular ATP deficit. Indeed, there is evidence to suggest that TDP-43 regulates glycolysis in hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines [131], and one study demonstrated that the abnormal localization of TDP-43 to mitochondria in cells from ALS/FTLD patients leads to the disassembly of the respiratory chain complex I and impairs mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation [181]. This has been corroborated by two more studies showing a pathological displacement of TDP-43, or its N- and C-terminal fragments, in mitochondria leading to impairment of mitochondrial functioning [34, 153]. Hyperglycemia could counteract this by providing more substrate (glucose) for cellular glucose metabolism, thereby partially replenishing the ATP deficit.

-

2.

Another possibility is that loss of TDP-43 function (and/or of other ALS- associated proteins) induces a Warburg-like state [176] in neurons, causing neurons to rely on readily available glucose to support their enhanced glycolysis. Hyperglycemia in T2DM might thus also help to offset the upregulated glycolysis caused by this metabolic maladaptation.

-

3.

Finally, high levels of glucose and/or lipids may counteract the cellular toxicity that arises from abnormal protein aggregation in ALS/FTLD neurons. Both wild-type TDP-43 and FUS regulate the expression of anti-oxidative genes, and their loss of function may lead to increased cell toxicity by reactive oxygen species (ROS) [115, 154]. Other evidence suggests that mitochondrial respiration is decreased in skeletal muscles of patients with T2DM [112]. This decrease in mitochondrial respiration could directly aid in reducing the toxicity due to ROS by reducing their production.

TDP-43 aggregation and defective neuronal glucose metabolism. Loss of TDP-43 function, caused by its abnormal aggregation in neurons, can potentially lead to defective glycolysis and to defects in the TCA cycle or electron transport chain, leading to decreased ATP levels. Additionally, TDP-43 loss of function might induce a Warburg effect in neurons, increasing their reliance on glycolysis for ATP production. Finally, TDP-43 aggregation can lead to increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) can be beneficial in each of these pathogenic mechanisms; hyperglycemia in T2DM provides readily available fuel for glucose metabolism and can also meet the increased requirement of glucose in neurons as a result of the Warburg effect, and it can counter ROS by replenishing levels of the anti-oxidant glutathione

In conclusion, there is a plausible biological rationale for the disease-modifying effect of metabolic disorders in ALS and FTLD based on the aforementioned hypotheses. How about other NDDs?

Metabolic dysfunction and other neurodegenerative disorders

The disease modifying effects of altered metabolism may not be limited to ALS and FTLD: they may be important for other NDDs [10, 137].

Huntington’s disease (HD) is a hereditary NDD caused by elongated CAG repeats in the Huntingtin (Htt) gene that lead to progressive increases in choreic movements and to neuropsychiatric dysfunction [146]. It is characterized by reduced mitochondrial ATP production in patient-derived lymphoblasts and skeletal muscles [96, 151, 156]. Importantly, a high BMI at the time of HD onset is associated with slower disease progression [117].

Similarly, patients with advanced Parkinson’s disease (PD), a movement disorder marked by ɑ-synuclein aggregates in neurons [87], exhibit unintended weight loss [14, 21], which may occur as a consequence of increased resting energy expenditure [89, 106]. Interestingly, similar to ALS, pre-morbid T2DM slows the progression of PD [31, 99].

Finally, metabolic factors also modify the course of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the most common form of late-onset dementia, which is characterized by synaptic and neuronal loss and by the formation of β-amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tau tangles in neurons [178]. While obesity in mid-life is associated with an increased risk of AD [85, 184], a higher BMI later in life, and slower BMI decline after onset of AD and slow disease progression [71].

Conclusions and future directions

In conclusion, the current clinical literature suggests that metabolic factors, such as BMI, diet and exercise, and metabolic disorders, such as T2DM and dyslipidemia, have a disease-modifying effect in ALS and potentially in FTLD (Table 1). These disease-modifying effects may be linked to the involvement of ALS and FTLD-related proteins in cellular and whole body metabolism (Table 2). However, altered metabolic pathways may also stimulate the formation of characteristic protein aggregates in ALS and FTLD (Fig. 1) or could modulate their downstream toxicity (Fig. 2).

It is imperative that future clinical studies of these diseases are carefully designed to reach conclusive answers. Studies on the effect of T2DM, dyslipidemia and BMI on ALS disease course should be prospective and should adjust for their individual and combined effects, as T2DM, dyslipidemia, and obesity are often co-morbid. Additional confounding factors, such as gender, ethnicity, diet, smoking, other vascular co-morbidities, and medications should be accounted for. It will also be important to correlate parameters of disease progression in ALS (e.g., the ALS-FRS) to those in metabolic disorders (e.g., serial measurements of HbA1c and lipid profile). Furthermore, it will be crucial to assess cognitive function when studying the effects of metabolic disorders on ALS because there may be different effects of metabolic disorders on motor vs. cognitive parameters [75, 76]. Finally, the disease-modifying effects of T2DM, dyslipidemia and BMI should be studied in more detail in patients with FTLD.

The recent development of autopsy brain banks for NDDs provides an excellent resource with which to study the effects of metabolic factors and dysfunction on the neuropathological pathways affected by ALS and FTLD. Through carefully designed clinicopathological studies, the extent and distribution of TDP-43 pathology in specific brain regions may be compared between ALS/FTD patients, who have or do not have a particular metabolic disorder. Similarly, a comparison of downstream pathways, such as those involved in neuronal loss, astrogliosis, autophagy, microglial activation, mitochondrial respiration, AMPK activity, and ROS levels, might provide important clues as to whether the effects of metabolic disorders on ALS/FTLD occur prior to or after protein aggregation occurs.

Most studies that have investigated a role for metabolic factors in the pathology of ALS/FTLD were performed in vivo in animal models, which have supported and advanced clinical findings in humans, where it is more difficult to control for various factors. Immortalized cancer cell lines and in neural stem cells are also excellent models to study; however, they can show metabolic adaptations that complicate interpretation of data derived from them [23, 68]. Other systems that may be excellent for studying metabolic effects in real time include alternative ex vivo systems, such as organotypic slice culture models [88], induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs)-derived neurons [108] or long-term complex neuronal cultures [159]. At the same time, they allow for genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, metabolomics, and epigenetic analyses. Finally, we need to better understand how the nuclear localization, aggregation, and phosphorylation of TDP-43 and FUS might be influenced by altered metabolic states, such as hyperglycemia and dyslipidemia, and how these states might protect neurons from damage. We also need to experimentally investigate the role of astrocytes and microglia in the potential disease-modifying effect of metabolic disorders in ALS and FTLD.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we have presented hypotheses that bridge the basic and clinical lines of research related to the disease-modifying effect of metabolic factors and disorders in ALS/FTLD. This review may serve as an inspiration for translationally oriented studies into the topic, which has important implications for prevention and treatment of ALS/FTLD.

Abbreviations

- ALS:

-

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- C9orf72:

-

C9 open reading frame 72

- EWS:

-

Ewing’s sarcoma

- FTD:

-

Frontotemporal dementia

- FTLD:

-

Frontotemporal lobar degeneration

- FUS:

-

Fused in sarcoma

- GLUT4:

-

Glucose transporter 4

- HDL:

-

High density lipoproteins

- LDL:

-

Low density lipoproteins

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- SOD1:

-

Superoxide dismutase 1

- T1DM:

-

Type 1 diabetes mellitus

- T2DM:

-

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

- TDP-43:

-

TAR DNA activating protein of 43 kDa

References

Aaron C, Beaudry G, Parker JA, Therrien M. Maple syrup decreases TDP-43 proteotoxicity in a Caenorhabditis elegans model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). J Agric Food Chem. 2016;64:3338–44.

Abdel-Khalik J, Yutuc E, Crick PJ, Gustafsson JA, Warner M, Roman G, Talbot K, Gray E, Griffiths WJ, Turner MR, Wang Y. Defective cholesterol metabolism in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Lipid Res. 2017;58:267–78.

Ahmed RM, MacMillan M, Bartley L, Halliday GM, Kiernan MC, Hodges JR, Piguet O. Systemic metabolism in frontotemporal dementia. Neurology. 2014b;83:1812–8.

Alfieri JA, Pino NS, Igaz LM. Reversible behavioral phenotypes in a conditional mouse model of TDP-43 proteinopathies. J Neurosci. 2014;34:15244–59.

Alfieri JA, Silva PR, Igaz LM. Early cognitive/social deficits and late motor phenotype in conditional wild-type TDP-43 transgenic mice. Front Aging Neurosci. 2016;8:310.

Almeida CS, Stanich P, Salvioni CCS, Diccini S. Assessment and nutrition education in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2016;74:902–8.

Ari C, Poff AM, Held HE, Landon CS, Goldhagen CR, Mavromates N, D’Agostino DP. Metabolic therapy with Deanna protocol supplementation delays disease progression and extends survival in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) mouse model. PLoS One. 2014;9:e103526.

Arnold ES, Ling S-C, Huelga SC, Lagier-Tourenne C, Polymenidou M, Ditsworth D, Kordasiewicz HB, McAlonis-Downes M, Platoshyn O, Parone PA, et al. ALS-linked TDP-43 mutations produce aberrant RNA splicing and adult-onset motor neuron disease without aggregation or loss of nuclear TDP-43. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2013;110:E736–45.

Baker M, Mackenzie IR, Pickering-Brown SM, Gass J, Rademakers R, Lindholm C, Snowden J, Adamson J, Sadovnick AD, Rollinson S, et al. Mutations in progranulin cause tau-negative frontotemporal dementia linked to chromosome 17. Nature. 2006;442:916–9.

Beal MF. Mitochondrial dysfunction in neurodegenerative diseases. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg. 1998;1366:211–23.

Beghi E, Logroscino G, Chiò A, Hardiman O, Millul A, Mitchell D, Swingler R, Traynor BJ. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, physical exercise, trauma and sports: results of a population-based pilot case-control study. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2010;11:289–92.

Beghi E, Pupillo E, Bonito V, Buzzi P, Caponnetto C, Chiò A, Corbo M, Giannini F, Inghilleri M, La Bella V, et al. Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of acetyl-L-carnitine for ALS. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2013;14:397–405.

Bene J, Hadzsiev K, Melegh B. Role of carnitine and its derivatives in the development and management of type 2 diabetes. Nutr Diabetes. 2018;8:8.

Beyer PL, Palarino MY, Michalek D, Busenbark K, Koller WC, Wellman NS. Weight change and body composition in patients with Parkinson’s disease. J Am Diet Assoc. 1995;95:979–83.

Blasco H, Madji Hounoum B, Dufour-Rainfray D, Patin F, Maillot F, Beltran S, Gordon PH, Andres CR, Corcia P. Vitamin D is not a protective factor in ALS. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2015;21:651–6.

Blasco H, Veyrat-Durebex C, Bocca C, Patin F, Vourc’h P, Nzoughet JK, Lenaers G, Andres CR, Simard G, Corcia P, Reynier P. Lipidomics Reveals Cerebrospinal-Fluid Signatures of ALS. Sci Rep. 2017;7:17652.

Buchan JR, Muhlrad D, Parker R. P bodies promote stress granule assembly in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol. 2008;183:441–55.

Caccamo A, Majumder S, Oddo S. Cognitive decline typical of frontotemporal lobar degeneration in transgenic mice expressing the 25-kDa C-terminal fragment of TDP-43. Am J Pathol. 2012;180:293–302.

Cady J, Koval ED, Benitez BA, et al. Trem2 variant p.r47h as a risk factor for sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71:449–53.

Camu W, Tremblier B, Plassot C, Alphandery S, Salsac C, Pageot N, Juntas-Morales R, Scamps F, Daures J-P, Raoul C. Vitamin D confers protection to motoneurons and is a prognostic factor of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35:1198–205.

Chen H, Zhang SM, Hernán MA, Willett WC, Ascherio A. Weight loss in Parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol. 2003;53:676–9.

Chen T, Ni Y, Ma X, Bao Y, Liu J, Huang F, Hu C, Xie G, Zhao A, Jia W, et al. Branched-chain and aromatic amino acid profiles and diabetes risk in Chinese populations. Sci Rep. 2016;6:20594.

Chen V, Shtivelman E. CC3/TIP30 regulates metabolic adaptation of tumor cells to glucose limitation. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:4941–53.

Chiang P-M, Ling J, Jeong YH, Price DL, Aja SM, Wong PC. Deletion of TDP-43 down-regulates Tbc1d1, a gene linked to obesity, and alters body fat metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2010;107:16320–4.

Chiò A, Calvo A, Dossena M, Ghiglione P, Mutani R, Mora G. ALS in Italian professional soccer players: the risk is still present and could be soccer-specific. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2009;10:205–9.

Cironi L, Riggi N, Provero P, Wolf N, Suvà M-L, Suvà D, Kindler V, Stamenkovic I. IGF1 is a common target gene of Ewing’s sarcoma fusion proteins in mesenchymal progenitor cells. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2634.

Cooper-Knock J, Bury JJ, Heath PR, Wyles M, Higginbottom A, Gelsthorpe C, Highley JR, Hautbergue G, Rattray M, Kirby J, et al. C9ORF72 GGGGCC expanded repeats produce splicing dysregulation which correlates with disease severity in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0127376.

Coughlan KA, Valentine RJ, Ruderman NB, Saha AK. AMPK activation: a therapeutic target for type 2 diabetes? Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2014;7:241–53.

Coughlan KS, Halang L, Woods I, Prehn JHM. A high-fat jelly diet restores bioenergetic balance and extends lifespan in the presence of motor dysfunction and lumbar spinal cord motor neuron loss in TDP-43 (A315T) mutant C57BL6/J mice. Dis Model Mech. 2016;9:1029–37.

Cruts M, Gijselinck I, van der Zee J, Engelborghs S, Wils H, Pirici D, Rademakers R, Vandenberghe R, Dermaut B, Martin J-J, et al. Null mutations in progranulin cause ubiquitin-positive frontotemporal dementia linked to chromosome 17q21. Nature. 2006;442:920–4.

D’Amelio M, Ragonese P, Callari G, Di Benedetto N, Palmeri B, Terruso V, Salemi G, Famoso G, Aridon P, Savettieri G. Diabetes preceding Parkinson’s disease onset. A case-control study. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2016;15:660–4.

D’Ovidio F, d'Errico A, Carnà P, Calvo A, Costa G, Chiò A. The role of pre-morbid diabetes on developing amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Eur J Neurol. 2018;25:164–70.

Dal Bello-Haas V, Florence JM. Therapeutic exercise for people with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis or motor neuron disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;5:CD005229.

Davis SA, Itaman S, Khalid-Janney CM, Sherard JA, Dowell JA, Cairns NJ, Gitcho MA. TDP-43 interacts with mitochondrial proteins critical for mitophagy and mitochondrial dynamics. Neurosci Lett. 2018;678:8–15.

Dedic SI, Stevic Z, Dedic V, Stojanovic VR, Milicev M, Lavrnic D. Is hyperlipidemia correlated with longer survival in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis? Neurol Res. 2012;34:576–80.

DeJesus-Hernandez M, Mackenzie IR, Boeve BF, Boxer AL, Baker M, Rutherford NJ, Nicholson AM, Finch NA, Gilmer HF, Adamson J, et al. Expanded GGGGCC hexanucleotide repeat in non-coding region of C9ORF72 causes chromosome 9p-linked frontotemporal dementia and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neuron. 2011;72:245–56.

Delaye JB, Patin F, Piver E, Bruno C, Vasse M, Vourc'h P, Andres CR, Corcia P, Blasco H. Low IDL-B and high LDL-1 subfraction levels in serum of ALS patients. J Neurol Sci. 2017;380:124–7.

Deng HX, Hentati A, Tainer JA, Iqbal Z, Cayabyab A, Hung WY, Getzoff ED, Hu P, Herzfeldt B, Roos RP, et al. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and structural defects in cu,Zn superoxide dismutase. Science. 1993;261:1047–51.

Deng J, Yang M, Chen Y, Chen X, Liu J, Sun S, Cheng H, Li Y, Bigio EH, Mesulam M, et al. FUS interacts with HSP60 to promote mitochondrial damage. PLoS Genet. 2015;11:e1005357.

Deshpande S, Abdollahi M, Wang M, Lanting L, Kato M, Natarajan R. Reduced autophagy by a microRNA-mediated signaling cascade in diabetes-induced renal glomerular hypertrophy. Sci Rep. 2018;8:6954.

Dodge JC, Treleaven CM, Fidler JA, Tamsett TJ, Bao C, Searles M, Taksir TV, Misra K, Sidman RL, Cheng SH, et al. Metabolic signatures of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis reveal insights into disease pathogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2013;110:10812–7.

Dodge JC, Treleaven CM, Pacheco J, Cooper S, Bao C, Abraham M, Cromwell M, Sardi SP, Chuang W-L, Sidman RL, et al. Glycosphingolipids are modulators of disease pathogenesis in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2015;112:8100–5.

Dorst J, Cypionka J, Ludolph AC. High-caloric food supplements in the treatment of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a prospective interventional study. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2013;14:533–6.

Dorst J, Kühnlein P, Hendrich C, Kassubek J, Sperfeld AD, Ludolph AC. Patients with elevated triglyceride and cholesterol serum levels have a prolonged survival inamyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol. 2011;258:613–7.

Drory VE, Bronipolsky T, Artamonov I, Nefussy B. Influence of statins treatment on survival in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 2008;273:81–3.

Duan W, Li X, Shi J, Guo Y, Li Z, Li C. Mutant TAR DNA-binding protein-43 induces oxidative injury in motor neuron-like cell. Neuroscience. 2010;169:1621–9.

Dupuis L, Corcia P, Fergani A, Gonzalez De Aguilar JL, Bonnefont-Rousselot D, Bittar R, Seilhean D, Hauw JJ, Lacomblez L, Loeffler JP, et al. Dyslipidemia is a protective factor in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurology. 2008;70:1004–9.

Dupuis L, Dengler R, Heneka MT, Meyer T, Zierz S, Kassubek J, Fischer W, Steiner F, Lindauer E, Otto M, et al. A Randomized, Double Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Pioglitazone in Combination with Riluzole in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. PLoS ONE. 2012;e37885:7.

Dupuis L, Oudart H, René F, Gonzalez de Aguilar J-L, Loeffler J-P. Evidence for defective energy homeostasis in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: benefit of a high-energy diet in a transgenic mouse model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:11159–64.

Edwards IR, Star K, Kiuru A. Statins, neuromuscular degenerative disease and an amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-like syndrome: an analysis of individual case safety reports from vigibase. Drug Saf. 2007;30:515–25.

Farrawell NE, Lambert-Smith IA, Warraich ST, Blair IP, Saunders DN, Hatters DM, Yerbury JJ. Distinct partitioning of ALS associated TDP-43, FUS and SOD1 mutants into cellular inclusions. Sci Rep. 2015;5:13416.

Fergani A, Oudart H, Gonzalez De Aguilar J-L, Fricker B, René F, Hocquette J-F, Meininger V, Dupuis L, Loeffler J-P. Increased peripheral lipid clearance in an animal model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Lipid Res. 2007;48:1571–80.

Fitzgerald KC, O’Reilly ÉJ, Falcone GJ, McCullough ML, Park Y, Kolonel LN, Ascherio A. Dietary n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid intake and risk of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71:1102–10.

Freedman DM, Kuncl RW, Weinstein SJ, Malila N, Virtamo J, Albanes D. Vitamin E serum levels and controlled supplementation and risk of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2013;14:246–51.

Gallo V, Vanacore N, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Vermeulen R, Brayne C, Pearce N, Wark PA, Ward HA, Ferrari P, Jenab M, et al. Physical activity and risk of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in a prospective cohort study. Eur J Epidemiol. 2016;31:255–66.

Gallo V, Wark PA, Jenab M, Pearce N, Brayne C, Vermeulen R, Andersen PM, Hallmans G, Kyrozis A, Vanacore N, et al. Prediagnostic body fat and risk of death from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: the EPIC cohort. Neurology. 2013;80:829–38.

Gitcho MA, Baloh RH, Chakraverty S, Mayo K, Norton JB, Levitch D, Hatanpaa KJ, White CL, Bigio EH, Caselli R, et al. TDP-43 A315T mutation in familial motor neuron disease. Ann Neurol. 2008;63:535–8.

Griffiths EJ, Rutter GA. Mitochondrial calcium as a key regulator of mitochondrial ATP production in mammalian cells. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg. 2009;1787:1324–33.

Gurney ME, Pu H, Chiu AY, Dal Canto MC, Polchow CY, Alexander DD, Caliendo J, Hentati A, Kwon YW, Deng HX, et al. Motor neuron degeneration in mice that express a human cu,Zn superoxide dismutase mutation. Science. 1994;264:1772–5.

Hamadeh MJ, Rodriguez MC, Kaczor JJ, Tarnopolsky MA. Caloric restriction transiently improves motor performance but hastens clinical onset of disease in the cu/Zn-superoxide dismutase mutant G93A mouse. Muscle Nerve. 2005;31:214–20.

Hamadeh MJ, Tarnopolsky MA. Transient caloric restriction in early adulthood hastens disease endpoint in male, but not female, Cu/Zn-SOD mutant G93A mice. Muscle Nerve. 2006;34:709–19.

Hayworth CR, Gonzalez-Lima F. Pre-symptomatic detection of chronic motor deficits and genotype prediction in congenic B6.SOD1(G93A) ALS mouse model. Neuroscience. 2009;164:975–85.

He Z, Ong CHP, Halper J, Bateman A. Progranulin is a mediator of the wound response. Nat Med. 2003;9:225–9.

Henriques A, Croixmarie V, Priestman DA, Rosenbohm A, Dirrig-Grosch S, D’Ambra E, Huebecker M, Hussain G, Boursier-Neyret C, Echaniz-Laguna A, et al. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and denervation alter sphingolipids and up-regulate glucosylceramide synthase. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24:7390–405.

Herrero-Martín D, Osuna D, Ordóñez JL, Sevillano V, Martins AS, Mackintosh C, Campos M, Madoz-Gúrpide J, Otero-Motta AP, Caballero G, et al. Stable interference of EWS–FLI1 in an Ewing sarcoma cell line impairs IGF-1/IGF-1R signalling and reveals TOPK as a new target. Br J Cancer. 2009;101:80–90.

Holler CJ, Taylor G, McEachin ZT, Deng Q, Watkins WJ, Hudson K, Easley CA, Hu WT, Hales CM, Rossoll W, et al. Trehalose upregulates progranulin expression in human and mouse models of GRN haploinsufficiency: a novel therapeutic lead to treat frontotemporal dementia. Mol Neurodegener. 2016;11:46.

Hollinger SK, Okosun IS, Mitchell CS. Antecedent disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: what is protecting whom? Front Neurol. 2016;7:47.

Hruzova M, Zamboni N, Jessberger S. Hippocampal neural stem cells rapidly change their metabolic profile during neuronal differentiation in cell culture. Matters Sel. 2016;2:e201603000016.

Huang H-Y, Hopper AK. Separate responses of karyopherins to glucose and amino acid availability regulate nucleocytoplasmic transport. Mol Biol Cell. 2014;25:2840–52.

Huang R, Guo X, Chen X, Zheng Z, Wei Q, Cao B, Zeng Y, Shang H. The serum lipid profiles of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients: A study from south-west China and a meta-analysis. Amyot Lat Scler Frontot Deg. 2015;16:359–65.

Hughes TF, Borenstein AR, Schofield E, Wu Y, Larson EB. Association between late-life body mass index and dementia: the Kame Project. Neurology. 2009;72:1741–6.

Huisman MHB, Seelen M, de Jong SW, Dorresteijn KRIS, van Doormaal PTC, van der Kooi AJ, de Visser M, Schelhaas HJ, van den Berg LH, Veldink JH. Lifetime physical activity and the risk of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2013;84:976–81.

Janssens J, Wils H, Kleinberger G, Joris G, Cuijt I, Ceuterick-de Groote C, Van Broeckhoven C, Kumar-Singh S. Overexpression of ALS-associated p.M337V human TDP-43 in mice worsens disease features compared to wild-type human TDP-43 mice. Mol Neurobiol. 2013;48:22–35.

Jawaid A, Brown JA, Schulz PE. Diabetes mellitus in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Dr Jekyll or Mr Hyde? Eur J Neurol. 2015;22:1419–20.

Jawaid A, Salamone AR, Strutt AM, Murthy SB, Wheaton M, McDowell EJ, Simpson E, Appel SH, York MK, Schulz PE. ALS disease onset may occur later in patients with pre-morbid diabetes mellitus. Eur J Neurol. 2010a;17:733–9.

Jawaid A, Murthy SB, Wilson AM, Qureshi SU, Amro MJ, Wheaton M, Simpson E, Harati Y, Strutt AM, York MK, et al. A decrease in body mass index is associated with faster progression of motor symptoms and shorter survival in ALS. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2010b;11:542–8.

Jawaid A, Paganoni S, Schulz PE. Trials of anti-diabetic drugs in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: proceed with caution? Neurodegener Dis. 2014;13:205–8.

Jin Y, Oh K, Oh S, Baek H, Kim SH, Park Y. Dietary intake of fruits and beta-carotene is negatively associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis risk in Koreans: a case-control study. Nutr Neurosci. 2014;17:104–8.

Kabashi E, Valdmanis PN, Dion P, Spiegelman D, McConkey BJ, Velde CV, Bouchard J-P, Lacomblez L, Pochigaeva K, Salachas F, et al. TARDBP mutations in individuals with sporadic and familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat Genet. 2008;40:572–4.

Kalkonde YV, Jawaid A, Qureshi SU, Shirani P, Wheaton M, Pinto-Patarroyo GP, Schulz PE. Medical and environmental risk factors associated with frontotemporal dementia: a case-control study in a veteran population. Alzheimers Dement. 2012;8:204–10.

Kapeli K, Pratt GA, Vu AQ, Hutt KR, Martinez FJ, Sundararaman B, Batra R, Freese P, Lambert NJ, Huelga SC, et al. Distinct and shared functions of ALS-associated proteins TDP-43, FUS and TAF15 revealed by multisystem analyses. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12143.

Karam C, Barrett MJ, Imperato T, MacGowan DJL, Scelsa S. Vitamin D deficiency and its supplementation in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Clin Neurosci. 2013;20:1550–3.

Kim S-M, Kim H, Kim J-E, Park KS, Sung J-J, Kim SH, Lee K-W. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis is associated th Hypolipidemia at the presymptomatic stage in mice. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17985.

Kim WS, Jary E, Pickford R, He Y, Ahmed RM, Piguet O, Hodges JR, Halliday GM. Lipidomics Analysis of Behavioral Variant Frontotemporal Dementia: A Scope for Biomarker Development. Front Neurol. 2018;9:104.

Kivipelto M, Ngandu T, Fratiglioni L, et al. Obesity and vascular risk factors at midlife and the risk of dementia and alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2005;62:1556–60.

Lawton KA, Cudkowicz ME, Brown MV, Alexander D, Caffrey R, Wulff JE, Bowser R, Lawson R, Jaffa M, Milburn MV, Ryals JA, Berry JD. Biochemical alterations associated with ALS. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2012;13:110–8.

Lees AJ, Hardy J, Revesz T. Parkinson’s disease. Lancet. 2016;373:2055–66.

Leggett C, McGehee DS, Mastrianni J, Yang W, Bai T, Brorson JR. Tunicamycin produces TDP-43 cytoplasmic inclusions in cultured brain organotypic slices. J Neurol Sci. 2012;317:66–73.

Levi S, Cox M, Lugon M, Hodkinson M, Tomkins A. Increased energy expenditure in Parkinson’s disease. BMJ Br Med J. 1990;301:1256–7.

Li H, Zhou B, Liu J, Li F, Li Y, Kang X, Sun H, Wu S. Administration of progranulin (PGRN) triggers ER stress and impairs insulin sensitivity via PERK-eIF2α-dependent manner. Cell Cycle. 2015;14:1893–907.

Li Y, Xu S, Mihaylova MM, Zheng B, Hou X, Jiang B, Park O, Luo Z, Lefai E, Shyy JY, et al. AMPK phosphorylates and inhibits SREBP activity to attenuate hepatic steatosis and atherosclerosis in diet-induced insulin-resistant mice. Cell Metab. 2011;13:376–88.

Ling S-C, Polymenidou M, Cleveland DW. Converging mechanisms in ALS and FTD: disrupted RNA and protein homeostasis. Neuron. 2013;79:416–38.

Liu J, Li H, Zhou B, Xu L, Kang X, Yang W, Wu S, Sun H. PGRN induces impaired insulin sensitivity and defective autophagy in hepatic insulin resistance. Mol Endocrinol. 2015a;29:528–41.

Liu Y, Pattamatta A, Zu T, Reid T, Bardhi O, Borchelt DR, Yachnis AT, Ranum LPW. C9orf72 BAC mouse model with motor deficits and neurodegenerative features of ALS/FTD. Neuron. 2016;90:521–34.

Liu YJ, Ju TC, Chen HM, Jang YS, Lee LM, Lai HL, Tai HC, Fang JM, Lin YL, Tu PH, Chern Y. Activation of AMP-activated protein kinase α1 mediates mislocalization of TDP-43 in amyotrophiclateral sclerosis. Hum Mol Genet. 2015b;24:787–801.

Lodi R, Schapira AHV, Manners D, Styles P, Wood NW, Taylor DJ, Warner TT. Abnormal in vivo skeletal muscle energy metabolism in Huntington’s disease and dentatorubropallidoluysian atrophy. Ann Neurol. 2000;48:72–6.

Logroscino G. Motor neuron disease: are diabetes and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis related? Nat Rev Neurol. 2015;11:488–90.

Longstreth WT, McGuire V, Koepsell TD, Wang Y, Van Belle G. Risk of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and history of physical activity: a population-based case-control study. Arch Neurol. 1998;55:201–6.

Lu L, Fu D, Li H, Liu A, Li J, Zheng G. Diabetes and risk of Parkinson’s disease: an updated meta-analysis of case-control studies. PLoS One. 2014;9:e85781.

Mackenzie IRA. The neuropathology and clinical phenotype of FTD with progranulin mutations. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114:49–54.

Mackenzie IRA, Neumann M. FET proteins in frontotemporal dementia and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain Res. 2012;1462:40–3.

Mackenzie IRA, Rademakers R, Neumann M. TDP-43 and FUS in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:995–1007.

Manzo E, O'Conner AG, Barrows JM, Shreiner DD, Birchak GJ, Zarnescu DC. Medium-chain fatty acids, beta-hydroxybutyric acid and genetic modulation of the carnitine shuttle are protective in a Drosophila model of ALS based on TDP-43. Front Mol Neurosci. 2018;11:182.

Mariosa D, Beard JD, Umbach DM, Bellocco R, Keller J, Peters TL, Allen KD, Weimin Y, Sandler DP, Schmidt S, Fang F, Kamel F. Body Mass Index and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: A Study of US Military Veterans. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;185:362–71.

Mariosa D, Kamel F, Bellocco R, Ye W, Fang F. Association between diabetes and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in Sweden. Eur J Neurol. 2015;22:1436–42.

Markus HS, Cox M, Tomkins AM. Raised resting energy expenditure in Parkinson’s disease and its relationship to muscle rigidity. Clin Sci. 1992;83:199–204.

Matsubara T, Mita A, Minami K, Hosooka T, Kitazawa S, Takahashi K, Tamori Y, Yokoi N, Watanabe M, Matsuo E, et al. PGRN is a key Adipokine mediating high fat diet-induced insulin resistance and obesity through IL-6 in adipose tissue. Cell Metab. 2012;15:38–50.

McKinney CE. Using induced pluripotent stem cells derived neurons to model brain diseases. Neural Regen Res. 2017;12:1062–7.

McKinsey EL, Parrish JK, Irwin AE, Niemeyer BF, Kern HB, Birks DK, Jedlicka P. A novel oncogenic mechanism in Ewing sarcoma involving IGF pathway targeting by EWS/Fli1-regulated microRNAs. Oncogene. 2011;30:4910–20.

Milanese M, Zappettini S, Onofri F, Musazzi L, Tardito D, Bonifacino T, Messa M, Racagni G, Usai C, Benfenati F, et al. Abnormal exocytotic release of glutamate in a mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurochem. 2011;116:1028–42.

Mitchell CS, Hollinger SK, Goswami SD, Polak MA, Lee RH, Glass JD. Antecedent disease is less prevalent in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurodegener Dis. 2015;15:109–13.

Mogensen M, Sahlin K, Fernström M, Glintborg D, Vind BF, Beck-Nielsen H, Højlund K. Mitochondrial respiration is decreased in skeletal muscle of patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2007;56:1592–9.

Mook-Kanamori DO, Römisch-Margl W, Kastenmüller G, Prehn C, Petersen AK, Illig T, Gieger C, Wang-Sattler R, Meisinger C, Peters A, Adamski J, Suhre K. Increased amino acids levels and the risk of developing of hypertriglyceridemia in a 7-year follow-up. J Endocrinol Investig. 2014;37:369–74.

Morselli E, Maiuri MC, Markaki M, Megalou E, Pasparaki A, Palikaras K, Criollo A, Galluzzi L, Malik SA, Vitale I, et al. Caloric restriction and resveratrol promote longevity through the Sirtuin-1-dependent induction of autophagy. Cell Death Dis. 2010;1:e10.

Moujalled D, Grubman A, Acevedo K, Yang S, Ke YD, Moujalled DM, Duncan C, Caragounis A, Perera ND, Turner BJ, et al. TDP-43 mutations causing amyotrophic lateral sclerosis are associated with altered expression of RNA-binding protein hnRNP K and affect the Nrf2 antioxidant pathway. Hum Mol Genet. 2017;26:1732–46.

Moura MC, Novaes MRCG, Eduardo EJ, Zago YSSP, Freitas RDNB, Casulari LA. Prognostic factors in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a population-based study. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0141500.

Myers RH, Sax DS, Koroshetz WJ, Mastromauro C, Cupples LA, Kiely DK, Pettengill FK, Bird ED. Factors associated with slow progression in Huntington’s disease. Arch Neurol. 1991;48:800–4.

Nefussy B, Hirsch J, Cudkowicz ME, Drory VE. Gender-based effect of statins on functional decline in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 2011;300:23–7.

Neumann M, Sampathu DM, Kwong LK, Truax AC, Micsenyi MC, Chou TT, Bruce J, Schuck T, Grossman M, Clark CM, et al. Ubiquitinated TDP-43 in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science. 2006;314:130–3.

Nguyen AD, Nguyen TA, Martens LH, Mitic LL, Farese RV Jr. Progranulin: at the interface of neurodegenerative and metabolic diseases. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2017;24:597–606.

Nieves J, Gennings C, Factor-Litvak P, Hupf J, Singleton J, Sharf V, Oskarsson B, Fernandes Filho J, Sorenson E, D’Amico E, et al. Association between dietary intake and function in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. JAMA Neurol. 2016;73:1425–32.

O’Reilly ÉJ, Wang H, Weisskopf MG, Fitzgerald KC, Falcone G, McCullough ML, Thun M, Park Y, Kolonel LN, Ascherio A. Premorbid body mass index and risk of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2013;14:205–11.

Okamoto K, Kihira T, Kondo T, Kobashi G, Washio M, Sasaki S, Yokoyama T, Miyake Y, Sakamoto N, Inaba Y, et al. Lifestyle factors and risk of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a case-control study in Japan. Ann Epidemiol. 2017;19:359–64.

Paganoni S, Deng J, Jaffa M, Cudkowicz ME, Wills A-M. Body mass index, not dyspidemia, is an independent predictor of survival in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Muscle Nerve. 2011;44:20–4.

Paganoni S, Hyman T, Shui A, Allred P, Harms M, Liu J, Maragakis N, Schoenfeld D, Yu H, Atassi N, et al. Pre-morbid type 2 diabetes mellitus is not a prognostic factor in ALS. Muscle Nerve. 2015;52:339–43.

Pahlich S, Quero L, Roschitzki B, Leemann-Zakaryan RP, Gehring H. Analysis of Ewing sarcoma (EWS)-binding proteins: interaction with hnRNP M, U, and RNA-helicases p68/72 within protein−RNA complexes. J Proteome Res. 2009;8:4455–65.

Palamiuc L, Schlagowski A, Ngo ST, Vernay A, Dirrig-Grosch S, Henriques A, Boutillier A, Zoll J, Echaniz-Laguna A, Loeffler J, et al. A metabolic switch toward lipid use in glycolytic muscle is an early pathologic event in a mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. EMBO Mol Med. 2015;7:526–46.

Park M, Yi J-W, Kim E-M, Yoon I-J, Lee E-H, Lee H-Y, Ji K-Y, Lee K-H, Jang J-H, Oh S-S, et al. Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 (TREM2) promotes adipogenesis and diet-induced obesity. Diabetes. 2015a;64:117–27.

Park JH, Kang H-J, Lee YK, Kang H, Kim J, Chung JH, Chang JS, McPherron AC, Lee SB. Inactivation of EWS reduces PGC-1α protein stability and mitochondrial homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2015b;112:6074–9.

Park M, Choi H, Kang H-S. Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 induces obesity by promoting adipogenesis (P3107). J Immunol. 2016;190:43.15.

Park Y-Y, Kim SB, Han HD, Sohn B-H, Kim J-H, Liang J, Lu Y, Mills GB, Sood AK, Lee J-S. TARDBP regulates glycolysis in hepatocellular carcinoma by regulating PFKP through miR-520. Hepatology. 2013;58:182–91.

Pasinelli P, Houseweart MK, Brown RH, Cleveland DW. Caspase-1 and -3 are sequentially activated in motor neuron death in cu,Zn superoxide dismutase-mediated familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:13901–6.

Patel BP, Safdar A, Raha S, Tarnopolsky MA, Hamadeh MJ. Caloric restriction shortens lifespan through an increase in lipid peroxidation, inflammation and apoptosis in the G93A mouse, an animal model of ALS. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9386.

Patin F, Corcia P, Vourc’h P, Nadal-Desbarats L, Baranek T, Goossens JF, Marouillat S, Dessein AF, Descat A, Madji HB, Bruno C, Leman S, Andres CR, Blasco H. Omics to explore amyotrophic lateral sclerosis evolution: the central role of arginine and proline metabolism. Mol Neurobiol. 2017;54:5361–74.

Polymenidou M, Cleveland DW. The seeds of neurodegeneration: prion-like spreading in ALS. Cell. 2011;147:498–508.

Prieur A, Tirode F, Cohen P, Delattre O. EWS/FLI-1 silencing and gene profiling of Ewing cells reveal downstream oncogenic pathways and a crucial role for repression of insulin-like growth factor binding protein 3. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:7275–83.

Procaccini C, Santopaolo M, Faicchia D, Colamatteo A, Formisano L, de Candia P, Galgani M, De Rosa V, Matarese G. Role of metabolism in neurodegenerative disorders. Metab Clin Exp. 2016;65:1376–90.

Pupillo E, Messina P, Giussani G, Logroscino G, Zoccolella S, Chiò A, Calvo A, Corbo M, Lunetta C, Marin B, et al. Physical activity and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a European population-based case–control study. Ann Neurol. 2014;75:708–16.

Qu H, Deng H, Hu Z. Plasma progranulin concentrations are increased in patients with type 2 diabetes and obesity and correlated with insulin resistance. Mediat Inflamm. 2013;2013:360190.

Rafiq MK, Lee E, Bradburn M, McDermott CJ, Shaw PJ. Effect of lipid profile on prognosis in the patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: insights from the olesoxime clinical trial. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2015;16:478–84.

Reich-Slotky R, Andrews J, Buchsbaum R, Levy D, Kaufmann P, Thompson J. Body mass index (BMI) as predictor of ALSFRS-r score decline in ALS patients (P07.085). Neurology. 2013;80:P07.085.

Renton AE, Majounie E, Waite A, Simón-Sánchez J, Rollinson S, Gibbs JR, Schymick JC, Laaksovirta H, van Swieten JC, Myllykangas L, et al. A hexanucleotide repeat expansion in C9ORF72 is the cause of chromosome 9p21-linked ALS-FTD. Neuron. 2011;72:257–68.

Reyes ET, Perurena OH, Festoff BW, Jorgensen R, Moore WV. Insulin resistance in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 1984;63:317–24.

Ringholz GM, Appel SH, Bradshaw M, Cooke NA, Mosnik DM, Schulz PE. Prevalence and patterns of cognitive impairment in sporadic ALS. Neurol. 2005;65:586–90.

Ripps ME, Huntley GW, Hof PR, Morrison JH, Gordon JW. Transgenic mice expressing an altered murine superoxide dismutase gene provide an animal model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1995;92:689–93.

Roos RAC. Huntington’s disease: a clinical review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2010;5:40.

Rosen DR, Siddique T, Patterson D, Figlewicz DA, Sapp P, Hentati A, Donaldson D, Goto J, O’Regan JP, Deng H-X, et al. Mutations in cu/Zn superoxide dismutase gene are associated with familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nature. 1993;362:59–62.

Rosenbohm A, Nagel G, Peter RS, Brehme T, Koenig W, Dupuis L, Rothenbacher D, Ludolph AC. Association of serum retinol-binding protein 4 concentration with risk for and prognosis of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. JAMA Neurology. 2018;75:600.

Rozen S, Cudkowicz ME, Bogdanov M, Matson WR, Kristal BS, Beecher C, Harrison S, Vouros P, Flarakos J, Vigneau-Callahan K, Matson TD, Newhall KM, Beal MF, Brown RH Jr, Kaddurah-Daouk R. Metabolomic analysis and signatures in motor neuron disease. Metabolomics. 2005;1:101–8.

Ryan CL, Baranowski DC, Chitramuthu BP, Malik S, Li Z, Cao M, Minotti S, Durham HD, Kay DG, Shaw CA, et al. Progranulin is expressed within motor neurons and promotes neuronal cell survival. BMC Neurosci. 2009;10:130.

Saft C, Zange J, Andrich J, Müller K, Lindenberg K, Landwehrmeyer B, Vorgerd M, Kraus PH, Przuntek H, Schöls L. Mitochondrial impairment in patients and asymptomatic mutation carriers of Huntington’s disease. Mov Disord. 2005;20:674–9.

Sakamoto K, Holman GD. Emerging role for AS160/TBC1D4 and TBC1D1 in the regulation of GLUT4 traffic. Am J Phys Endocrinol Metab. 2008;295:E29–37.

Salvatori I, Ferri A, Scaricamazza S, Giovannelli I, Serrano A, Rossi S, D’Ambrosi N, Cozzolino M, Giulio AD, et al. Differential toxicity of TAR DNA-binding protein 43 isoforms depends on their submitochondriallocalization in neuronal cells. J Neurochem. 2018;146:585–97.

Sánchez-Ramos C, Tierrez A, Fabregat-Andrés O, Wild B, Sánchez-Cabo F, Arduini A, Dopazo A, Monsalve M. PGC-1α regulates translocated in Liposarcoma activity: role in oxidative stress gene expression. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;15:325–37.

Schmitt F, Hussain G, Dupuis L, Loeffler J-P, Henriques A. A plural role for lipids in motor neuron diseases: energy, signaling and structure. Front Cell Neurosci. 2014;8:25.

Seong IS, Ivanova E, Lee J-M, Choo YS, Fossale E, Anderson M, Gusella JF, Laramie JM, Myers RH, Lesort M, et al. HD CAG repeat implicates a dominant property of huntingtin in mitochondrial energy metabolism. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:2871–80.

Shimizu T, Nagaoka U, Nakayama Y, Kawata A, Kugimoto C, Kuroiwa Y, Kawai M, Shimohata T, Nishizawa M, Mihara B, et al. Reduction rate of body mass index predicts prognosis for survival in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a multicenter study in Japan. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2012;13:363–6.

Sørensen HT, Riis AH, Lash TL, Pedersen L. Statin use and risk of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and other motor neuron disorders. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3:413–7.

Soscia D, Belle A, Fischer N, Enright H, Sales A, Osburn J, Benett W, Mukerjee E, Kulp K, Pannu S, Wheeler E. Controlled placement of multiple CNS cell populations to create complex neuronal cultures. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0188146.

Sreedharan J, Blair IP, Tripathi VB, Hu X, Vance C, Rogelj B, Ackerley S, Durnall JC, Williams KL, Buratti E, et al. TDP-43 mutations in familial and sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science. 2008;319:1668–72.

Stallings NR, Puttaparthi K, Dowling KJ, Luther CM, Burns DK, Davis K, Elliott JL. TDP-43, an ALS linked protein, regulates fat deposition and glucose homeostasis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e71793.

Stallings NR, Puttaparthi K, Luther CM, Burns DK, Elliott JL. Progressive motor weakness in transgenic mice expressing human TDP-43. Neurobiol Dis. 2010;40:404–14.

Stoica R, Paillusson S, Gomez-Suaga P, Mitchell JC, Lau DHW, Gray EH, Sancho RM, Vizcay-Barrena G, De Vos KJ, Shaw CE, et al. ALS/FTD-associated FUS activates GSK-3β to disrupt the VAPB–PTPIP51 interaction and ER–mitochondria associations. EMBO Rep. 2016;17:1326–42.

Stribl C, Samara A, Trümbach D, Peis R, Neumann M, Fuchs H, Gailus-Durner V, Hrabě de Angelis M, Rathkolb B, Wolf E, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction and decrease in body weight of a transgenic Knock-in mouse model for TDP-43. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:10769–84.

Sun Y, Lu C-J, Chen R-C, Hou W-H, Li C-Y. Risk of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in patients with diabetes: a nationwide population-based cohort study. J Epidemiol. 2015;25:445–51.