Abstract

Background

TAR DNA binding protein 43 (TDP-43) is the main disease protein in most patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and about 50% of patients with frontotemporal dementia (FTD). TDP-43 pathology is not restricted to patients with missense mutations in TARDBP, the gene encoding TDP-43, but also occurs in ALS/FTD patients without known genetic cause or in patients with various other ALS/FTD gene mutations. Mutations in progranulin (GRN), which result in a reduction of ~ 50% of progranulin protein (PGRN) levels, cause FTD with TDP-43 pathology. How loss of PGRN leads to TDP-43 pathology and whether or not PGRN expression protects against TDP-43-induced neurodegeneration is not yet clear.

Methods

We studied the effect of PGRN on the neurodegenerative phenotype in TDP-43(A315T) mice.

Results

PGRN reduced the levels of insoluble TDP-43 and histology of the spinal cord revealed a protective effect of PGRN on the loss of large axon fibers in the lateral horn, the most severely affected fiber pool in this mouse model. Overexpression of PGRN significantly slowed down disease progression, extending the median survival by approximately 130 days. A transcriptome analysis did not point towards a single pathway affected by PGRN, but rather towards a pleiotropic effect on different pathways.

Conclusion

Our findings reveal an important role of PGRN in attenuating mutant TDP-43-induced neurodegeneration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) are two related neurodegenerative disorders with overlapping molecular disease pathways. In FTD, neuronal loss in the frontal and anterior temporal lobes gives rise to behavioral changes and/or language impairments [1]. In ALS, the degeneration of upper and lower motor neurons causes progressive muscle weakness limiting survival to 2–5 years after symptom onset [2]. TAR DNA binding protein 43 (TDP-43) has been identified as an important disease protein for both ALS and FTD, as most patients with ALS, and up to 50% of patients with FTD develop TDP-43 pathology [3]. While most ALS/FTD cases are sporadic, a familial component can be identified in approximately 10% and 40% of ALS and FTD patients, respectively [1, 2, 4]. Mutations in several genes can cause both ALS and FTD or ALS-FTD, including mutations in the gene encoding TDP-43 itself [5,6,7]. In FTD patients, TDP-43 pathology is frequently associated with progranulin haploinsufficiency caused by loss-of-function mutations in the progranulin (GRN) gene [8,9,10]. Such mutations, which result in ~ 50% reductions of progranulin protein (PGRN) levels [11,12,13], also rarely cause FTD-ALS [14] and genetic variations in GRN have been associated with the age of onset, disease duration and risk of disease in ALS [15].

The preferential expression of PGRN in neurons and activated microglia points towards its most important functions in the central nervous system [16, 17]. PGRN is an important modulator of neuroinflammation and of microglial recruitment and activation [18, 19], as PGRN shortage results in an exaggerated inflammatory response after brain insults [20, 21] and in an impaired microglial phagocytosis [22]. In addition, PGRN has neurotrophic effects which include stimulation of neurite outgrowth, of synaptic connectivity and of neuronal survival [11, 23,24,25,26,27,28]. At the subcellular level, PGRN ends up in late endosomes/lysosomes and facilitates the lysosomal clearance function [29], possibly by controlling the acidification of lysosomes [30] and by acting as a chaperone of degradation enzymes [31,32,33].

How shortage of PGRN causes TDP-43 pathology remains incompletely understood, but dysfunctional lysosomal degradation pathways with reduced clearance of TDP-43 could contribute to the accumulation of pathological TDP-43 species [34, 35].

We previously showed that PGRN has neuroprotective effects in a zebrafish model of mutant TDP-43 induced motor neuron damage [36]. However, its effect in rodent TDP-43 models remains unexplored. We therefore studied the therapeutic potential of PGRN in a mutant TDP-43(A315T) mouse model with a progressive motor phenotype [37, 38].

Methods

Mice

The TDP-43(A315T) and GRN overexpressing mice were bred in a C57BL/6 J background and maintained as previously described [38, 39] and all mice in the study were fed DietGel®boost (ClearH20, Maine, USA). This gel food contains all necessary nutrients, but is a soft, high calorie, easily digestible paste containing hardly any fibers. Female littermates were used for the experiments. All experiments were approved by the Ethical Committee of the KU Leuven (P148/2011).

Gene expression analysis

For qRT-PCR analysis, first-strand cDNA was synthesized using SuperScript III (Invitrogen). PCR reactions were performed using TaqMan assays (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) for Iba1, TARDBP, Tardbp and Grn. Gene expression was normalized to the expression of three reference genes using SYBR Green reagents (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with the following primer pairs: adaptor-related protein complex 3, delta 1 subunit (Ap3d1) (forward, 5’-CAAGGGCAGTATCGACCGC-3′; reverse, 5’-GATCTCGTCAATGCACTGGGA-3′), MON2 homolog (Mon2) (forward, 5’-CTACAGTCCGACAGGTCGTGA-3′; reverse, 5’-CGGCACTGGAGGTTCTATATCTC-3′) and F-box protein 38 (Fbxo38) (forward, 5’-ATGGGACCACGAAAGAAAAGTG-3′; reverse, 5’-TAGCTTCCGAGAGAGGCATTC-3′). Expression levels were analyzed using qBase+ (v.3.0, Biogazelle, Zwijnaarde, Belgium).

RNA sequencing was performed by the Nucleomics Core Facility (VIB, Leuven, Belgium). From extracted RNA, libraries were made using the Illumina TruSeq Stranded mRNA Library protocol. These libraries were sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq single-end 51 bp and an average of 19.3 million reads per sample (range 17.7–21.2). To estimate the expression of the transcript of every sample, reads were counted using Salmon (v0.8.1) [40] against the Ensembl transcript for the mouse reference genome mm10. Gene expression as then estimate from the protein coding transcripts using the tximport function the R-package tximport (v1.6.0) [41]. Differential expression of coding genes was performed using the R-package EdgeR (v3.20.5) [42]. Genes were regarded as differentially expressed when the FDR-adjusted p-value (Benjamini and Hochberg method) was smaller than 0.05 and the absolute value of the log fold change (logFC) was larger or equal to 1. Genes were regarded as corrected by GRN overexpression, when the gene was differentially expressed between NTG and TDP-43(A315T) (FDR < 0.05 and |logFC| ≥ 1) mice but not differentially expressed between NTG and TDP-43(A315T)xGRN mice (unadjusted p-value ≥0.05). Pathway analysis were performed using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (QIAGEN). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) on gene ontology (GO) terms was performed using the logFC values of the differential expression analysis and the R-packages gage (v2.28.0) and gageData_(v2.16.0).

Histology

Spinal cords from mice of 200–240 days were fixed overnight in 4% glutaraldehyde in PBS (pH 7.4), washed with PBS and post-fixed for 2 h in 1% osmium tetroxide. Dehydration of the samples was performed using an ethanol gradient as follows: 15 min in 50%, 15 min in 70%, 15 min in 90% and 3 times 15 min in 100% ethanol. After a washing step in 100% propylene oxide (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA), the samples were embedded using increasing ratios of TAAB medium (TAAB 812 Resin Premix kit 812, TAAB Laboratories, Aldermaston, Berkshire, United Kingdom) and propylene oxide: 1–2 h with a 1:2 ratio, overnight with a 1:1 ratio, 1–2 h with a 2:1 ratio and twice 2 h with 100% TAAB medium. The samples were subsequently baked for 72 h in a 60 °C oven before cutting 1 μm semi thin sections with a Reichert Ultracut microtome (Reichert, Wien, Austria). Sections were stained 20 s with toluidine blue. Photographs of the lateral column of the spinal cord were taken with a Zeiss Imager.M1, using a 100X objective. To measure the average area of all axon fibers, a custom analysis macro was created in ImageJ (v.1.49, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA) which was then applied to each image.

Western blot

Proteins were extracted from brain cortex samples using T-PER reagent (Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with Complete™, EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich). Protein concentrations were determined using the microBCA kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. To study the insoluble protein fraction, equal amounts of protein extract were first centrifuged at 4 °C at maximum speed during 20 min. The obtained supernatant was used as the soluble fraction. The pellet was washed and gently vortexed with 1000 μl RIPA buffer (Sigma) containing cOmplete™ (Sigma), and PhosSTOP™ (Sigma). After a second centrifugation step the pellet was dissolved in sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and used as the insoluble fraction.

Reducing sample buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was added to samples containing equal amounts of protein and heated for 5 min at 95 °C before separation on a sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide electrophoresis gel. After electrophoresis, the proteins were transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany). Non-specific binding was blocked using 5% blotting-grade blocker (Bio-rad, Hercules, CA, USA), diluted in Tris-Buffered Saline Tween (50 mM TRIS, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween-20; Applichem, Darmstadt, Germany) for 1 h at room temperature before. Primary antibodies were incubated overnight at 4 °C, diluted in blocking-grade buffer and directed against TDP-43 (1:1000, ProteinTech, Chicago, IL, USA), GAPDH (1:2500, Thermo Fisher Scientific) PGRN (1:200 R&D systems) and CTSD (1:1000, Abcam). HRP-coupled secondary antibodies (1:5000, Dako, Agilent), diluted in TBS-T, were incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Blots were visualized using the enhanced chemiluminescent substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and imaged with an ImageQuant LAS 4000 system (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden). Western blots were quantified using ImageQuant TL (v. 7.0). To quantify total TDP-43 levels, the sum of the intensities of the mTDP-43 band and the hTDP-43 band was used. CTSD activity measurements were performed using the CTSD activity assay kit (Abcam), following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (v 7.01, GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA), unless otherwise stated. Statistical tests used are indicated in the figure legends. Non-parametric testing was performed when the data was not normally distributed.

Results

Progranulin overexpression reduces insoluble TDP-43 levels in TDP-43(A315T) mice

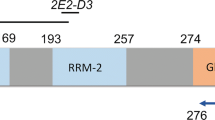

To study the therapeutic potential of human GRN overexpression on TDP-43(A315T) induced neurodegeneration, TDP-43(A315T) mice, which express human mutant TDP-43 under the control of the prion promoter, were crossed with human GRN overexpressing mice, which carry a copy of human GRN cDNA in the ROSA26 locus resulting in human PGRN protein overexpression [39]. TDP-43(A315T) mice develop a progressive motor phenotype when sudden death due to intestinal obstructions is prevented by putting them on a diet only consisting of an easy to digest nutrient gel [37, 38].

Overexpression of PGRN had no effect on the TDP-43(A315T) transgene expression (Fig. 1a) and did not affect the downregulation of endogenous TDP-43 by the human TDP-43 transgene (Fig. 1b and Additional file 1: Figure S2A). No significant changes in mouse Grn and the microglial marker Iba1 were observed in TDP-43(A315T) mice and PGRN overexpression did not influence the expression of these genes (Fig. 1c-d). Overexpression of PGRN also left the levels of endogenous PGRN unaltered (Fig. 2a-b and Additional file 1: Figure S1A-B). Shortage of PGRN has previously been shown to impair lysosomal function and to induce lysosomal enzymes, such as cathespin D (CTSD) [31, 34]. Overexpression of PGRN did not result in altered CTSD levels (Fig. 2c-d and Additional file 1: Figure S1C-D) or a change in CTSD activity (Additional file 1: Figure S1E-H).

PGRN overexpression has no effect on TDP-43 RNA levels. RNA expression of the human TDP-43(A315T) transgene (a), mouse Tardbp (b) and mouse Grn (c) in the spinal cord is unchanged by PGRN overexpression. ***p < 0.001, one-way ANOVA. d No significant changes were observed in Iba1 expression in the spinal cord. Data are shown as mean ± SEM

Human PGRN overexpression has no effect on mouse PGRN or CTSD protein levels. a-b Protein expression of mouse PGRN in brain and spinal cord from NTG, TDP-43(A315T) and TDP-43(A315T)xGRN mice. c-d Protein expression of human PGRN and mouse CTSD in brain and spinal cord NTG, TDP-43(A315T) and TDP-43(A315T)xGRN mice. °Aspecific band

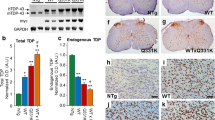

TDP-43(A315T) mice do not display clear mislocalisation of TDP-43 or TDP-43 inclusions. However, accumulation of TDP-43 in the insoluble fraction was observed in TDP-43(A315T) mice, especially in the spinal cord (Fig. 3). Interestingly, overexpression of PGRN reduced this insoluble fraction of TDP-43, most efficiently in the spinal cord. This suggests that PGRN can reduce the formation or enhance the clearance of insoluble TDP-43 species.

PGRN overexpression reduces insoluble TDP-43 levels. a, e Western blot analysis of total, soluble and insoluble TDP-43 in brain (a) and spinal cord (e) from NTG, TDP-43(A315T) and TDP-43(A315T)xGRN mice. Quantification of blots (b-d and f-h) are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 3 per group, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.001, *** p < 0.0001, Tukey-Kramer multiple comparison test)

Degeneration of large axon fibers in the lateral spinal cord is prevented by progranulin overexpression

A prominent loss of spinal motor neuron cell bodies is lacking in TDP-43(A315T) mice [38]. The most dramatic pathological hallmark of this mouse model is the loss of large axon fibers in the lateral column of the spinal cord [37, 38]. The number of small axon fibers (1–4 μm2) in this region was not affected by TDP-43(A315T) expression and was also not changed by PGRN overexpression (Fig. 4a-b). However, the overall number of large axon fibers was significantly reduced in TDP-43(A315T) mice and the overexpression of PGRN mitigated this phenotype (Fig. 4c).

PGRN overexpression prevents degeneration of large axon fibers. a Schematic overview of the region in the lateral spinal cord used for the analysis of axon fibers as indicated by the black square. b No difference was found in the number of small axon fibers (1–4 μm2) in this region. c Representative images of the axon fibers in the lateral spinal cord (Scale bar = 10 μm). d The mean number of large axon fibers in NTG and TDP-43(A315T)xGRN mice was significantly higher across all size groups, compared to TDP-43(A315T) mice (n = 6–9 per group, *p < 0.05, Wilcoxon signed-rank test). Data are shown as mean ± SEM

Progranulin overexpression extends disease duration in TDP-43(A315T) mice

Next, the effect of PGRN was assessed on the clinical phenotype of TDP-435A315T) mice. The disease onset, as determined by the appearance of a swimming gait and the inability to lift up the lower part of the body from the ground, which is quite variable in this model, was not altered by PGRN overexpression (Fig. 5a). In contrast, PGRN overexpression did significantly increase the survival of TDP-43(A315T) mice (Fig. 5b). Also the disease duration after onset, was clearly prolonged by the overexpression of PGRN (Fig. 5c).

PGRN overexpression increases survival and disease duration in TDP-43(A315T) mice. a Disease onset is not affected by PGRN overexpression (n = 26 and 54 for TDP-43(A315T) and TDP-43(A315T)xGRN mice, respectively). b The survival is significantly increased by PGRN overexpression. Median survival: 364 d (TDP-43(A315T)) versus 491 d (TDP-43(A315T)xGRN). **p < 0.01, Log-rank test. c PGRN overexpression significantly increased the survival after symptom onset. Median disease duration: 91 d (TDP-43(A315T)) versus 150 d (TDP-43(A315T)xGRN). **p < 0.01, Log-rank test

With these results, we provide evidence for a protective effect of PGRN on TDP-43(A315T) induced neurodegeneration, as the increase in disease duration was accompanied by reduced insoluble TDP-43 levels and protection of large axon fibers in the spinal cord.

Transcriptome analysis does not reveal a single pathway underlying PGRN neuroprotection

To further characterize the neuroprotective effects of PGRN, we performed a transcriptome analysis on the spinal cord from 50-day-old NTG, TDP-43(A315T) and TDP-43(A315T)xGRN mice (n = 3 per group). The downregulation of endogenous mouse Tardbp in TDP-43(A315T) mice was confirmed and this was not altered by PGRN overexpression (Additional file 1: Figure S2A). The expression of total GRN RNA in the TDP-43(A315T)xGRN mice compared to endogenous mouse Grn was estimated to be 2.36 (95% CI 1.00–3.72) (Additional file 1: Figure S2A). The samples clustered according to genotype (Additional file 1: Figure S2B) and a gene set enrichment analysis revealed especially reduced expression in ribosomal and mitochondrial genes in TDP-43(A315T) mice compared to NTG controls (Additional file 1: Table S1). PGRN overexpression particularly influenced extracellular matrix genes, but did not correct the reduced expression in ribosomal and mitochondrial genes. No changes in microglial or lysosomal genes were observed. There was a differential gene expression in 35 genes when comparing TDP-43(A315T) to NTG controls (Additional file 1: Table S2). For 7 of those genes, the expression was corrected by PGRN overexpression (Additional file 1: Figure S2C). A pathway analysis of these genes did not provide evidence for a protective effect of PGRN on one specific pathway, it rather hinted at a pleiotropic effect of PGRN on different pathways, some with possible importance for ALS-FTD (Rsad2 is an ER stress-induced protein involved in cell defense, Top2a is a topoisomerase involved in replication- and transcription-associated DNA breaks and repair, Fbxo22 is part of the ubiquitin ligase complex involved in ubiquitination and degradation of proteins). Interestingly, using String DB, the proteins encoded by these 3 genes clustered in a protein-protein interaction network (Additional file 1: Figure S2D). The effect of PGRN on the expression of the key player, Rsad2, was confirmed using Western blot (Additional file 1: Figure S3). Although little is known about the concert function of these gene products, both Rsad2 and Fbxo22 are involved in the innate and adaptive immune system in the central nervous system and Top2 is involved in inflammation-induced DNA damage [43, 44].

Discussion

Neuronal TDP-43 positive inclusions are the main pathological hallmark in most ALS patients and in about half of FTD patients and the degree of TDP-43 pathology correlates with the degree of neuronal loss [45]. In this study, we investigated the possibility of a therapeutic effect of PGRN on the disease progression of an ALS mouse model with mutant TDP-43(A315T) overexpression. By crossbreeding human PGRN overexpression mice to TDP-43(A315T) mice, we could indeed observe a significant improvement in the survival of these mutant TDP-43 mice. PGRN reduced the levels of insoluble TDP-43 and protected large axon fibers in the lateral column of the spinal cord of these animals. This suggests that PGRN has protective effects by lessening the production or enhancing the clearance of insoluble TDP-43 species. A transcriptome analysis did not provide evidence for a neuroprotective effect of PGRN through modulation of microglial activation or lysosomal function, two processes known to be dependent on PGRN [46]. On the contrary, we recently described a neurotrophic effect of PGRN after nerve crush which could be linked to lysosomal effects of PGRN as chaperone of the lysosomal protease CTSD or cathepsin D [31]. CTSD was identified using a similar design analysis in which we looked for genes with differential expression which had corrected expression levels after PGRN treatment. However, these experiments were performed in Grn-deficient mice, with known defects in lysosomal function. In this study, the TDP-43(A315T) mice had normal baseline PGRN levels. Although our transcriptome analysis did not point towards lysosomal function, there is some evidence that TDP-43 pathology could potentially be a direct consequence of defective autophagy and lysosomal function: inhibition of lysosomes resulted in the redistribution of TDP-43 protein to the cytoplasm [47] and PGRN was shown to be necessary to maintain the autophagic flux to prevent the accumulation of pathological forms of TDP-43 [35].

How PGRN specifically reduces insoluble TDP-43 levels and prevents TDP-43 mediated neurodegeneration requires further investigation. Of the 35 genes with differential expression in the mutant TDP-43 mice, PGRN corrected the levels of 7 of them. Some of these are indirectly connected to each other in a protein interaction network and can be linked to innate or adaptive immunity. Radical S-Adenosyl Methionine Domain containing 2 (Rsad2) is an interferon-inducible ER protein that functions as an innate immunity factor [43] and is also upregulated in mutant PINK1 fibroblasts [48]. Finally, Fbxo22 is a member of the ubiquitin ligase complex important for ubiquitination and degradation of proteins and also plays a role in macrophage activation [49]. Topoisomerase II alfa (Top2a) catalyzes transient breaking and ligation of dsDNA during transcription and translation and has been involved in inflammation-induced DNA damage [44]. Apart from effects on neuroinflammation, effects on DNA damage, which is an emerging disease mechanism in ALS-FTD [50], could be of interest.Top2a and GRN are upregulated in glioblastomas [51, 52] and GRN overexpression was shown to protect against DNA damage induced by the Top2a inhibitor tomozolomide in glioblastoma cell lines [52].

In addition, a direct neurotrophic effect of PGRN may occur without changes in gene expression. Neuroprotective effects of PGRN have also been observed in models of other brain disorders, suggesting that PGRN may have beneficial effects in various brain diseases not restricted to FTD with GRN haploinsufficiency [53]. PGRN treatment was shown to be therapeutic in mouse models for Parkinson’s disease [54, 55], Alzheimer’s disease [22] and stroke [56, 57] and the neuroprotective effects were mostly attributed to modulation of neuroinflammation, effects.

Conclusion

Our data show that PGRN reduces insoluble TDP-43 levels, slows down axonal degeneration and prolongs survival in mutant TDP-43 mice. With our study, we add TDP-43 linked neurodegeneration to the list of disorders for which PGRN treatment could be beneficial.

Abbreviations

- ALS:

-

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- EDTA:

-

Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- FDR:

-

False discovery rate

- FTD:

-

Frontotemporal dementia

- GO:

-

Gene ontology

- GRN :

-

(Progranulin gene)

- GSEA:

-

Gene set enrichment analysis

- logFC:

-

Log fold change

- PBS:

-

Phosphate buffered saline

- PGRN:

-

(Progranulin protein)

- qRT PCR:

-

Quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction

- TDP-43:

-

TAR DNA binding protein 43

- T-PER:

-

Tissue Protein Extraction Reagent

References

Neary D, Snowden J, Mann D. Frontotemporal dementia. Lancet Neurol. 2005;4:771–80.

Hardiman O, Al-Chalabi A, Chio A, Corr EM, Logroscino G, Robberecht W, Shaw PJ, Simmons Z, van den Berg LH. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17085.

Neumann M, Sampathu DM, Kwong LK, Truax AC, Micsenyi MC, Chou TT, Bruce J, Schuck T, Grossman M, Clark CM, et al. Ubiquitinated TDP-43 in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science. 2006;314:130–3.

van Es MA, Hardiman O, Chio A, Al-Chalabi A, Pasterkamp RJ, Veldink JH, van den Berg LH. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet. 2017;390:2084–98.

Kabashi E, Valdmanis PN, Dion P, Spiegelman D, McConkey BJ, Vande Velde C, Bouchard JP, Lacomblez L, Pochigaeva K, Salachas F, et al. TARDBP mutations in individuals with sporadic and familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat Genet. 2008;40:572–4.

Van Deerlin VM, Leverenz JB, Bekris LM, Bird TD, Yuan W, Elman LB, Clay D, Wood EM, Chen-Plotkin AS, Martinez-Lage M, et al. TARDBP mutations in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with TDP-43 neuropathology: a genetic and histopathological analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:409–16.

Sreedharan J, Blair IP, Tripathi VB, Hu X, Vance C, Rogelj B, Ackerley S, Durnall JC, Williams KL, Buratti E, et al. TDP-43 mutations in familial and sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science. 2008;319:1668–72.

Cruts M, Gijselinck I, van der Zee J, Engelborghs S, Wils H, Pirici D, Rademakers R, Vandenberghe R, Dermaut B, Martin JJ, et al. Null mutations in progranulin cause ubiquitin-positive frontotemporal dementia linked to chromosome 17q21. Nature. 2006;442:920–4.

Baker M, Mackenzie IR, Pickering-Brown SM, Gass J, Rademakers R, Lindholm C, Snowden J, Adamson J, Sadovnick AD, Rollinson S, et al. Mutations in progranulin cause tau-negative frontotemporal dementia linked to chromosome 17. Nature. 2006;442:916–9.

Mackenzie IR. The neuropathology and clinical phenotype of FTD with progranulin mutations. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114:49–54.

Van Damme P, Van Hoecke A, Lambrechts D, Vanacker P, Bogaert E, van Swieten J, Carmeliet P, Van Den Bosch L, Robberecht W. Progranulin functions as a neurotrophic factor to regulate neurite outgrowth and enhance neuronal survival. J Cell Biol. 2008;181:37–41.

Ghidoni R, Benussi L, Glionna M, Franzoni M, Binetti G. Low plasma progranulin levels predict progranulin mutations in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Neurology. 2008;71:1235–9.

Sleegers K, Brouwers N, Van Damme P, Engelborghs S, Gijselinck I, van der Zee J, Peeters K, Mattheijssens M, Cruts M, Vandenberghe R, et al. Serum biomarker for progranulin-associated frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Ann Neurol. 2009;65:603–9.

Benussi L, Ghidoni R, Pegoiani E, Moretti DV, Zanetti O, Binetti G. Progranulin Leu271LeufsX10 is one of the most common FTLD and CBS associated mutations worldwide. Neurobiol Dis. 2009;33:379–85.

Sleegers K, Brouwers N, Maurer-Stroh S, van Es MA, Van Damme P, van Vught PW, van der Zee J, Serneels S, De Pooter T, Van den Broeck M, et al. Progranulin genetic variability contributes to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurology. 2008;71:253–9.

Petkau TL, Leavitt BR. Progranulin in neurodegenerative disease. Trends Neurosci. 2014;37:388–98.

De Muynck L, Van Damme P. Cellular effects of progranulin in health and disease. J Mol Neurosci. 2011;45:549–60.

Pickford F, Marcus J, Camargo LM, Xiao Q, Graham D, Mo JR, Burkhardt M, Kulkarni V, Crispino J, Hering H, Hutton M. Progranulin is a chemoattractant for microglia and stimulates their endocytic activity. Am J Pathol. 2011;178:284–95.

Lui H, Zhang J, Makinson SR, Cahill MK, Kelley KW, Huang HY, Shang Y, Oldham MC, Martens LH, Gao F, et al. Progranulin deficiency promotes circuit-specific synaptic pruning by microglia via complement activation. Cell. 2016;165:921–35.

Yin F, Banerjee R, Thomas B, Zhou P, Qian L, Jia T, Ma X, Ma Y, Iadecola C, Beal MF, et al. Exaggerated inflammation, impaired host defense, and neuropathology in progranulin-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 2010;207:117–28.

Tanaka Y, Matsuwaki T, Yamanouchi K, Nishihara M. Exacerbated inflammatory responses related to activated microglia after traumatic brain injury in progranulin-deficient mice. Neuroscience. 2013;231:49–60.

Minami SS, Min SW, Krabbe G, Wang C, Zhou Y, Asgarov R, Li Y, Martens LH, Elia LP, Ward ME, et al. Progranulin protects against amyloid beta deposition and toxicity in Alzheimer's disease mouse models. Nat Med. 2014;20:1157–64.

Tapia L, Milnerwood A, Guo A, Mills F, Yoshida E, Vasuta C, Mackenzie IR, Raymond L, Cynader M, Jia W, Bamji SX. Progranulin deficiency decreases gross neural connectivity but enhances transmission at individual synapses. J Neurosci. 2011;31:11126–32.

Petkau TL, Neal SJ, Milnerwood A, Mew A, Hill AM, Orban P, Gregg J, Lu G, Feldman HH, Mackenzie IR, et al. Synaptic dysfunction in progranulin-deficient mice. Neurobiol Dis. 2012;45:711–22.

Gass J, Lee WC, Cook C, Finch N, Stetler C, Jansen-West K, Lewis J, Link CD, Rademakers R, Nykjaer A, Petrucelli L. Progranulin regulates neuronal outgrowth independent of Sortilin. Mol Neurodegener. 2012;7:33.

De Muynck L, Herdewyn S, Beel S, Scheveneels W, Van Den Bosch L, Robberecht W, Van Damme P. The neurotrophic properties of progranulin depend on the granulin E domain but do not require sortilin binding. Neurobiol Aging. 2013;34:2541–7.

Gao X, Joselin AP, Wang L, Kar A, Ray P, Bateman A, Goate AM, Wu JY. Progranulin promotes neurite outgrowth and neuronal differentiation by regulating GSK-3beta. Protein Cell. 2010;1:552–62.

Chitramuthu BP, Baranowski DC, Kay DG, Bateman A, Bennett HP. Progranulin modulates zebrafish motoneuron development in vivo and rescues truncation defects associated with knockdown of survival motor neuron 1. Mol Neurodegener. 2010;5:41.

Kao AW, McKay A, Singh PP, Brunet A, Huang EJ. Progranulin, lysosomal regulation and neurodegenerative disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2017;18:325–33.

Tanaka Y, Suzuki G, Matsuwaki T, Hosokawa M, Serrano G, Beach TG, Yamanouchi K, Hasegawa M, Nishihara M. Progranulin regulates lysosomal function and biogenesis through acidification of lysosomes. Hum Mol Genet. 2017;26:969–88.

Beel S, Moisse M, Damme M, De Muynck L, Robberecht W, Van Den Bosch L, Saftig P, Van Damme P. Progranulin functions as a cathepsin D chaperone to stimulate axonal outgrowth in vivo. Hum Mol Genet. 2017;26:2850–63.

Evers BM, Rodriguez-Navas C, Tesla RJ, Prange-Kiel J, Wasser CR, Yoo KS, McDonald J, Cenik B, Ravenscroft TA, Plattner F, et al. Lipidomic and transcriptomic basis of lysosomal dysfunction in Progranulin deficiency. Cell Rep. 2017;20:2565–74.

Valdez C, Wong YC, Schwake M, Bu G, Wszolek ZK, Krainc D. Progranulin-mediated deficiency of cathepsin D results in FTD and NCL-like phenotypes in neurons derived from FTD patients. Hum Mol Genet. 2017;26:4861–72.

Gotzl JK, Mori K, Damme M, Fellerer K, Tahirovic S, Kleinberger G, Janssens J, van der Zee J, Lang CM, Kremmer E, et al. Common pathobiochemical hallmarks of progranulin-associated frontotemporal lobar degeneration and neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. Acta Neuropathol. 2014;127:845–60.

Chang MC, Srinivasan K, Friedman BA, Suto E, Modrusan Z, Lee WP, Kaminker JS, Hansen DV, Sheng M. Progranulin deficiency causes impairment of autophagy and TDP-43 accumulation. J Exp Med. 2017;214:2611–28.

Laird AS, Van Hoecke A, De Muynck L, Timmers M, Van Den Bosch L, Van Damme P, Robberecht W. Progranulin is neurotrophic in vivo and protects against a mutant TDP-43 induced axonopathy. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13368.

Wegorzewska I, Bell S, Cairns NJ, Miller TM, Baloh RH. TDP-43 mutant transgenic mice develop features of ALS and frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:18809–14.

Herdewyn S, Cirillo C, Van Den Bosch L, Robberecht W, Vanden Berghe P, Van Damme P. Prevention of intestinal obstruction reveals progressive neurodegeneration in mutant TDP-43 (A315T) mice. Mol Neurodegener. 2014;9:24.

Herdewyn S, De Muynck L, Van Den Bosch L, Robberecht W, Van Damme P. Progranulin does not affect motor neuron degeneration in mutant SOD1 mice and rats. Neurobiol Aging. 2013;34:2302–3.

Patro R, Duggal G, Love MI, Irizarry RA, Kingsford C. Salmon provides fast and bias-aware quantification of transcript expression. Nat Methods. 2017;14:417–9.

Soneson C, Love MI, Robinson MD. Differential analyses for RNA-seq: transcript-level estimates improve gene-level inferences. F1000Research. 2015;4:1521.

McCarthy DJ, Chen Y, Smyth GK. Differential expression analysis of multifactor RNA-Seq experiments with respect to biological variation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:4288–97.

Cho H, Proll SC, Szretter KJ, Katze MG, Gale M Jr, Diamond MS. Differential innate immune response programs in neuronal subtypes determine susceptibility to infection in the brain by positive-stranded RNA viruses. Nat Med. 2013;19:458–64.

Yang YC, Chou HY, Shen TL, Chang WJ, Tai PH, Li TK. Topoisomerase II-mediated DNA cleavage and mutagenesis activated by nitric oxide underlie the inflammation-associated tumorigenesis. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;18:1129–40.

Mackenzie IR, Arzberger T, Kremmer E, Troost D, Lorenzl S, Mori K, Weng SM, Haass C, Kretzschmar HA, Edbauer D, Neumann M. Dipeptide repeat protein pathology in C9ORF72 mutation cases: clinico-pathological correlations. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;126:859–79.

Chitramuthu BP, Bennett HPJ, Bateman A. Progranulin: a new avenue towards the understanding and treatment of neurodegenerative disease. Brain. 2017;140:3081–104.

Ju JS, Fuentealba RA, Miller SE, Jackson E, Piwnica-Worms D, Baloh RH, Weihl CC. Valosin-containing protein (VCP) is required for autophagy and is disrupted in VCP disease. J Cell Biol. 2009;187:875–88.

Torres-Odio S, Key J, Hoepken HH, Canet-Pons J, Valek L, Roller B, Walter M, Morales-Gordo B, Meierhofer D, Harter PN, et al. Progression of pathology in PINK1-deficient mouse brain from splicing via ubiquitination, ER stress, and mitophagy changes to neuroinflammation. J Neuroinflammation. 2017;14:154.

Pilar AV, Reid-Yu SA, Cooper CA, Mulder DT, Coombes BK. GogB is an anti-inflammatory effector that limits tissue damage during Salmonella infection through interaction with human FBXO22 and Skp1. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002773.

Gao FB, Almeida S, Lopez-Gonzalez R. Dysregulated molecular pathways in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-frontotemporal dementia spectrum disorder. EMBO J. 2017;36:2931–50.

Arivazhagan A, Kumar DM, Sagar V, Patric IR, Sridevi S, Thota B, Srividya MR, Prasanna K, Thennarasu K, Mondal N, et al. Higher topoisomerase 2 alpha gene transcript levels predict better prognosis in GBM patients receiving temozolomide chemotherapy: identification of temozolomide as a TOP2A inhibitor. J Neuro-Oncol. 2012;107:289–97.

Bandey I, Chiou SH, Huang AP, Tsai JC, Tu PH. Progranulin promotes Temozolomide resistance of glioblastoma by orchestrating DNA repair and tumor stemness. Oncogene. 2015;34:1853–64.

Arrant AE, Filiano AJ, Unger DE, Young AH, Roberson ED. Restoring neuronal progranulin reverses deficits in a mouse model of frontotemporal dementia. Brain. 2017;140:1447–65.

Van Kampen JM, Baranowski D, Kay DG. Progranulin gene delivery protects dopaminergic neurons in a mouse model of Parkinson's disease. PLoS One. 2014;9:e97032.

Martens LH, Zhang J, Barmada SJ, Zhou P, Kamiya S, Sun B, Min SW, Gan L, Finkbeiner S, Huang EJ, Farese RV Jr. Progranulin deficiency promotes neuroinflammation and neuron loss following toxin-induced injury. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:3955–9.

Kanazawa M, Kawamura K, Takahashi T, Miura M, Tanaka Y, Koyama M, Toriyabe M, Igarashi H, Nakada T, Nishihara M, et al. Multiple therapeutic effects of progranulin on experimental acute ischaemic stroke. Brain. 2015;138:1932–48.

Egashira Y, Suzuki Y, Azuma Y, Takagi T, Mishiro K, Sugitani S, Tsuruma K, Shimazawa M, Yoshimura S, Kashimata M, et al. The growth factor progranulin attenuates neuronal injury induced by cerebral ischemia-reperfusion through the suppression of neutrophil recruitment. J Neuroinflammation. 2013;10:105.

Acknowledgements

WR is supported through the E. von Behring Chair for Neuromuscular and Neurodegenerative Disorders. PVD holds a senior clinical investigatorship of FWO-Vlaanderen. MDD is supported by a PhD fellowship from IWT.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the ALS Therapy Alliance, Opening the Future Fund (KU Leuven), the Fund for Scientific Research Flanders (FWO-Flanders), the Interuniversity Attraction Poles (IUAP) program P7/16 of the Belgian Federal Science Policy Office, the ALS Liga Belgium, Een hart voor ALS, Laeversfonds voor ALS-onderzoek, the Alzheimer Research Foundation (SAO-FRA), the Flemish Government initiated Flanders Impulse Program on Networks for Dementia Research (VIND), the European Union Joint Programme-Neurodegenerative Disease Research (JPND) project RiMod-FTD.

Availability of data and materials

All datasets generated or analyzed during the study are available upon request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SB, SH, RF, MDD and MM performed the experiments and statistical analysis. PVD, WR and LVDB designed and supervised the study. SB and PVD wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors revised and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the KU Leuven (P148/2011).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Table S1. Results of the gene set enrichment analysis. Table S2. List of the 35 differentially expressed genes when comparing NTG controls to TDP-43(A315T) mice. Figure S1. PGRN overexpression does not affect endogenous PGRN or CTSD levels/activity. Figure S2. RNAseq results. Figure S3. Western blot of Rsad2. (A) Western blot for Rsad2 in brain and spinal cord lysates from NTG, TDP-43(A315T) and TDP-43(A315T)xGRN mice. (B) Quantification of Rsad2 bands from brain and spinal cord of NTG, TDP-43(A315T) and TDP-43(A315T)xGRN mice (n = 3 per group, * p < 0.05, Tukey-Kramer multiple comparison test). (ZIP 1920 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Beel, S., Herdewyn, S., Fazal, R. et al. Progranulin reduces insoluble TDP-43 levels, slows down axonal degeneration and prolongs survival in mutant TDP-43 mice. Mol Neurodegeneration 13, 55 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13024-018-0288-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13024-018-0288-y