Abstract

Background

Pulmonary artery intimal spindle cell sarcomas are rare and carry with them a poor prognosis and high rate of recurrence. In extremely rare cases, this tumor can infiltrate the pulmonic valve and manifest as adult-onset pulmonic stenosis.

Case presentation

We report an unusual case of a patient with symptomatic, adult-onset severe pulmonic stenosis who was referred for possible balloon valvuloplasty but was subsequently found to have pulmonary artery intimal sarcoma infiltrating the pulmonary valve leading to progressive exertional dyspnea.

Conclusion

The presence of adult-onset pulmonic stenosis should prompt the clinician to investigate further as most cases of pulmonic stenosis are congenital in nature and present early in life. Careful diagnostic evaluation in concert with multimodal imaging should take place to arrive at the correct and challenging diagnosis of sarcoma-induced adult-onset severe pulmonic stenosis. Given the poor prognosis and rapid progression of disease, early diagnosis is crucial.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In the majority of cases, pulmonic stenosis is congenital in nature and is commonly diagnosed and treated in the pediatric population. The diagnosis of acquired pulmonic stenosis in adulthood is unusual and may represent an oncologic phenomenon and warrants a thorough workup to identify the etiology of the stenosis. Here we present a case of a patient with adult-onset pulmonic stenosis due to pulmonary artery intimal sarcoma and the multimodal and multidisciplinary efforts needed to diagnose and treat the patient.

Case presentation

A 79-year-old man with a 1-month history of progressive dyspnea and exercise intolerance was found to have severe pulmonic valve stenosis and was referred to our institution for balloon valvuloplasty. Prior medical history included coronary artery disease, hypertension and chronic kidney disease.

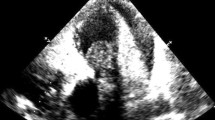

At the referring institution, the physical exam was notable for a III/VI systolic murmur best appreciated in the left upper sternal border. An electrocardiogram (EKG) demonstrated sinus rhythm with a right bundle branch block and a chest x-ray was normal. Transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) was reported as demonstrating severe pulmonic stenosis with a peak gradient of 100 mmHg and peak velocity of 5 m/s associated with right ventricular hypertrophy, severe tricuspid regurgitation and severe right atrial dilatation (Fig. 1, Additional files 1, 2, 3

Additional file 1: Movie S1. Movie of Fig. 1, Panel A demonstrating sarcoma infiltrating the pulmonic valve. (MP4 1935 kb)

Additional file 2: Movie S2. Movie of Fig. 1, Panel B demonstrating flow acceleration across the pulmonic valve. (MP4 2304 kb)

Additional file 3: Movie S3. Movie of Fig. 1, Panel D in short-axis view showing marked right ventricular hypertrophy. (MP4 3092 kb)

).

Transthoracic Echocardiogram. 2D TTE image demonstrates the sarcoma infiltrating the pulmonic valve (Panel a) leading to marked flow acceleration across the pulmonic valve on color Doppler imaging (Panel b) and spectral Doppler tracing with a peak velocity of 4.6 m/s and a peak gradient of 84 mmHg (Panel c). The presence of marked right ventricular hypertrophy (Panel d) implies chronic pressure overload of the right ventricle. Abbreviations: AV, aortic valve; LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; MPA, main pulmonary artery; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle; RVOT, right ventricular outflow tract

The patient was taken to the catheterization lab for planned balloon valvuloplasty but the procedure was canceled after angiography revealed an obstructive mass in the right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT) of unclear etiology extending into the main pulmonary artery (Fig. 2, Additional files 4, and 5

Additional file 4: Movie S4.

Movies of Fig. 2, Biplane angiogram in right anterior oblique. (MP4 2764 kb)

Additional file 5: Movie S5.

Left anterior oblique view (movie S5) revealing flow obstruction at the level of the pulmonic valve. (MP4 3061 kb)

). Contrast-enhanced computed tomographic (CT) angiogram and gadolinium-enhanced cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were obtained to better characterize the obstructive mass.

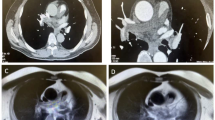

CT angiogram showed a fixed intravascular defect within the proximal main pulmonary artery arising from the pulmonic valve with mixed enhancement properties suggesting a thrombus versus a vascular mass; no other filling defects were noted (Fig. 3).

Cardiac MRI revealed a T1 and T2 hyperintense ovoid mass measuring 2.0 × 1.5 cm, and centered at the lateral aspect of the pulmonary valve in the region of the anterior sinus of Valsalva. The mass extended into the pulmonary artery resulting in severe pulmonic stenosis (Fig. 4). Neither CT nor MRI demonstrated malignant lesions anywhere else in the body.

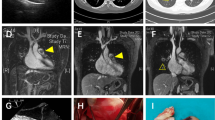

Given the CT and MRI findings, the mass was presumed to be a primary cardiac tumor and decision was made to proceed with surgical resection. A preoperative transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) corroborated CT and MRI findings (Fig. 5, Additional files 6, and 7

Additional file 6: Movie S6. Movie of Fig. 5, Panel A showing a large mass obstructing the pulmonic valve. (MP4 4720 kb)

Additional file 7: Movie S7. Movie of Fig. 5, Panel B showing a large mass obstructing the pulmonic valve. (MP4 4218 kb)

).

Intraoperative TEE. Intraoperative midesophageal TEE view at two short-axis levels of the aortic valve demonstrates a large mass obstructing the pulmonic valve which was subsequently shown to be spindle cell sarcoma. Abbreviations: AV, aortic valve; LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; MPA, main pulmonary artery; RA, right atrium; RVOT, right ventricular outflow tract

The patient underwent median sternotomy and longitudinal arteriotomy in the main pulmonary artery (MPA) that showed a fungating mass involving the pulmonary annulus and MPA with extension into the RVOT (Fig. 6). The tumor was resected en bloc and the RVOT was reconstructed using a pulmonary homograft. Surgical histopathology revealed increased mitotic activity and nuclear atypia. Immunohistochemical staining was positive for smooth muscle actin (SMA) consistent with intimal spindle cell sarcoma (Fig. 7).

Histopathology. Panel a Haematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) stained sections show spindled tumor cells lining the intimal surfaces of the pulmonary artery and pulmonic valve as well as forming nodules with infiltrative borders that are arranged in fascicles (original magnification 40×). Panel b Magnified H&E section demonstrates a high degree of nuclear atypia (original magnification 400×). Panel c Immunohistochemical staining demonstrates tumor cells that are positive for smooth muscle actin (SMA) (original magnification 400×)

Postoperatively, a TTE demonstrated normal pulmonary valve function and his dyspnea resolved. He was then referred for chemotherapy with pazopanib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, but was lost to follow up.

Discussion

The vast majority of cases of pulmonic stenosis in children and adults are due to congenital heart disease. Acquired pulmonic stenosis is rare with carcinoid syndrome, rheumatic fever and infective endocarditis accounting for the majority of cases [1]. Very rarely, pulmonic stenosis and RVOT obstruction are caused by tumors.

The majority of cardiac tumors are malignant and metastases of extracardiac malignancies [2]. The incidence of primary cardiac tumors, whether benign or malignant, is very low (approximately 0.02% in the general population) [2]. Most primary cardiac tumors are benign; malignant tumors account for only 15% of all primary cardiac tumors. Sarcomas are by far the most common primary cardiac malignancies [3, 4].

Here, we report a case of a malignant intimal sarcoma infiltrating the pulmonic valve, a very rare cause of adult-onset severe pulmonary stenosis and otherwise unexplained progressive exertional dyspnea. The patient in question was initially referred to our institution for balloon valvuloplasty – the treatment modality of choice for symptomatic, congenitally-acquired pulmonic stenosis. However, it is highly atypical for congenitally-acquired pulmonic stenosis to present late in life with symptoms. Therefore, the presentation of adult-onset symptomatic pulmonic stenosis should prompt a nuanced diagnostic workup to identify the correct diagnosis and optimal choice of treatment.

Intimal sarcoma was first described in 1923 by Moritz Mandelstamm [5]. Such tumors are thought to arise from multipotent mesenchymal cells of the intima of the great arteries [6]. Between 1923 and 2012, less than 200 cases of intimal sarcoma involving the great arteries have been described with the majority of reports focusing on histological features and surgical management [7]. When intimal sarcomas arise from the main pulmonary artery they tend to extend into the pulmonary artery branches and rarely involve the pulmonary valve and RVOT [8,9,10,11,12,13].

It has previously been reported that intimal sarcomas have a female predominance. However, a more recent study has shown an equal sex distribution with an average age of disease onset of 49.3 years (range 13-81 years) [14]. By the time of presentation, the disease is usually advanced and carries a poor prognosis with a median survival of only 17 months [15].

Establishing the diagnosis of intimal sarcoma is challenging. Pulmonary artery intimal sarcomas often present with cough, dyspnea and chest pain associated with radiological features suggestive of a thrombus or obstructive mass in the pulmonary artery [7]. The most common finding on physical examination is a systolic ejection murmur which is seen in 44% of patients [14]. The overall clinical presentation of pulmonary artery intimal sarcomas mimic pulmonary embolism and there are several reports in the literature of intimal sarcoma masquerading as pulmonary embolism [16,17,18,19].

The current diagnostic gold-standard is tissue sampling and immunohistochemical analysis. Intimal sarcomas can radiographically mimic thrombus and drastically alter clinical decision making. Therefore, preoperative, multimodality imaging is of paramount importance. Doppler echocardiography is the screening tool of choice and should be considered in all patients with suspected intracardiac masses as it allows for identification and characterization of the mass based on potential hemodynamic consequences [20]. Transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography have 93% and 97% sensitivity in detecting primary cardiac tumors, respectively [21]. Intimal sarcomas are highly vascularized tumors that readily demonstrate hyperenhancement with contrast perfusion echocardiography [22]. On the other hand, stromal tumors and thrombi demonstrate hypoenhancement. Other TTE findings suggestive of intimal sarcoma include a right sided location, right ventricular hypertrophy and a bulging or ovoid mass with involvement of the pulmonic valve or RVOT causing pulmonic stenosis [23].

Other imaging modalities that are useful in diagnosing intimal sarcoma include CT, cardiac MRI and positron emission tomography (PET) scans. On CT, intimal sarcomas are more likely to have a heterogeneous appearance with smooth, contiguous areas of spread, often expanding beyond the vessel wall, in contrast to thrombus [19]. On MRI, intimal sarcomas are more likely to demonstrate enhancement and vascularity after administration of contrast that allows for accurate anatomic localization. Finally, PET scans can aid in diagnosis and prognosis by showing tumor size, spread and distribution.

Radical surgical resection remains the only definitive mode of treatment. Without surgery the mean survival rate is 1.5 months and with surgery the chance of recurrence and spread remains high [15]. In certain cases, cardiac transplantation may prolong survival compared to treatment with local resection [24]. There are some reports of improved survival with adjuvant chemotherapy following resection, however, data are limited [25,26,27].

Conclusion

In summary, in patients presenting with symptomatic, adult-onset pulmonic stenosis with radiographic features of an obstruction in the pulmonary artery or RVOT, intimal sarcoma should be a consideration on the differential diagnosis. Early diagnosis is crucial as this disease is rapidly progressive and has a poor prognosis.

Abbreviations

- CT:

-

Contrast-enhanced computed tomographic

- EKG:

-

Electrocardiogram

- MPA:

-

Main pulmonary artery

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- PET:

-

Positron emissions tomography

- RVOT:

-

Right Ventricular Outflow Tract

- SMA:

-

Smooth muscle actin

- TEE:

-

Transesophageal echocardiogram

- TTE:

-

Transthoracic echocardiogram

References

Altrichter PM, Olson LJ, Edwards WD, et al. Surgical pathology of the pulmonary valve: a study of 116 cases spanning 15 years. Mayo Clin Proc. 1989;64:1352–60.

Reynen K. Frequency of primary tumors of the heart. Am J Cardiol. 1996;77:107.

Molina JE, Edwards JE, Ward HB. Primary cardiac tumors: experience at the University of Minnesota. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1990;38(Suppl 2):183–91.

Neuville A, Collin F, Bruneval P, et al. Intimal sarcoma is the most frequent primary cardiac sarcoma: clinicopathologic and molecular retrospective analysis of 100 primary cardiac sarcomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38:461–9.

Mandelstamm M. Uber primare Neubildungen des Derzen. Virchows Arch Pathol Anat. 1923;245:43–54.

Govender D, Pillay SV. Right pulmonary artery sarcoma. Pathology. 2001;33:243–5.

Levy E, Korach A, Amir G, et al. Undifferentiated sarcoma of the pulmonary artery mimicking pulmonary thromboembolic disease. Heart Lung Circ. 2006;15:62–3.

Shah DK, Joyce LD, Grogan M, et al. Recurrent pulmonary intimal sarcoma involving the right ventricular outflow tract. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;91:e41–2.

Scheidl S, Taghavi S, Reiter U, et al. Intimal sarcoma of the pulmonary valve. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;89:e25–7.

Hsing JM, Thakkar SG, Borden EC, et al. Intimal pulmonary artery sarcoma presenting as dyspnea: case report. Int Semin Surg Oncol. 2007;4:14.

Alsoufi B, Slater M, Smith PP, et al. Pulmonary artery sarcoma mimicking massive pulmonary embolus: a case report. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2006;14:e71–3.

Choi EY, Yoon YW, Kwon HM, et al. A case of pulmonary artery intimal sarcoma diagnosed with multislice CT scan with 3D reconstruction. Yonsei Med J. 2004;45:547–51.

Murthy MS, Meckstroth CV, Merkle BH, et al. Primary intimal sarcoma of pulmonary valve and trunk with osteogenic sarcomatous elements. Report of a case considered to be pulmonary embolus. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1976;100:649–51.

Cox JE, Chiles C, Aquino SL, et al. Pulmonary artery sarcomas: a review of clinical and radiologic features. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1997;21:750–5.

Wong HH, Gounaris I, McCormack A, et al. Presentation and management of pulmonary artery sarcoma. Clin Sarcoma Res. 2015;5:3.

Kerr KM. Pulmonary artery sarcoma masquerading as chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2005;2:108–12. quiz 113

Zurick AO III, Lenge De Rosen V, Tan CD, et al. Pulmonary artery intimal sarcoma masquerading as pulmonary embolism. Circulation. 2011;124:1180–1.

Timmers L, Bove T, De Pauw M. Intimal sarcoma of the pulmonary artery: a report of two cases. Acta Cardiol. 2009;64:677–9.

Kauczor HU, Schwickert HC, Mayer E, et al. Pulmonary artery sarcoma mimicking chronic thromboembolic disease: computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging findings. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1994;17:185–9.

Saric M, Armour AC, Arnaout MS, et al. Guidelines for the use of echocardiography in the evaluation of a cardiac source of embolism. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2016;29:1–42.

Meng Q, Lai H, Lima J, et al. Echocardiographic and pathologic characteristics of primary cardiac tumors: a study of 149 cases. Int J Cardiol. 2002;84:69–75.

Kirkpatrick JN, Wong T, Bednarz JE, et al. Differential diagnosis of cardiac masses using contrast echocardiographic perfusion imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:1412–9.

Kim MJ, Kim MS, Park J-H, et al. Pulmonary artery Angiosarcoma confused with acute pulmonary Thromboembolism: focusing on clinical and Echocardiographic features in the differentiation of two categories. Journal of Cardiovascular Ultrasound. 2015;23:44–7.

Agaimy A, Rosch J, Weyand M, et al. Primary and metastatic cardiac sarcomas: a 12-year experience at a German heart center. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2012;5:928–38.

Genoni M, Biraima AM, Bode B, et al. Combined resection and adjuvant therapy improves prognosis of sarcomas of the pulmonary trunk. J Cardiovasc Surg. 2001;42:829–33.

Uchida A, Tabata M, Kiura K, et al. Successful treatment of pulmonary artery sarcoma by a two-drug combination chemotherapy consisting of ifosfamide and epirubicin. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2005;35:417–9.

Mayer F, Aebert H, Rudert M, et al. Primary malignant sarcomas of the heart and great vessels in adult patients--a single-center experience. Oncologist. 2007;12:1134–42.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the pathology images provided by James Suh, formerly of the Department of Pathology, New York University Langone Medical Center.

Funding

No funding to report.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AM and MS gathered data, performed literature review and co-wrote the case report. SPM performed the surgery, provided intra-op images of the mass and helped review the final manuscript. CRW and AR were directly involved in the care of this patient and helped review the final manuscript. LAL and PB were involved in image acquisition and provided radiologic interpretation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Informed consent obtained.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Manmadhan, A., Malhotra, S.P., Weinberg, C.R. et al. Intimal spindle cell sarcoma masquerading as adult-onset symptomatic pulmonic stenosis: a case report and review of the literature. J Cardiothorac Surg 12, 93 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13019-017-0654-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13019-017-0654-9