Abstract

Background

There is increasing focus on long-term survival, function and quality-of-life for trauma patients. There are few studies tracking longitudinal changes in functional outcome over time. The goal of our study was to compare the Glasgow Outcome Scale-Extended (GOSE) at 6 months and 12 months in blunt trauma survivors with an Injury Severity Score (ISS) of more than 15.

Methods

Using the Singapore National Trauma Registry 2011–2013, patients with 6-month GOSE and 12-month GOSE scores were analysed. Patients were grouped into three categories—those with the same score at 6 months and 12 months, an improvement in score, and a worse score at 12 months. Ordinal regression was used to identify risk factors for improved score. Patients with missing scores at either 6 months or 12 months were excluded.

Results

We identified 478 patients: 174 had an improvement in score, 233 stayed the same, and 71 had worse scores at 12 months compared to 6 months. On univariate ordinal regression, the following variables were associated with same or better function at 12-months compared to 6-months: male gender, being employed pre-injury, thoracic Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS) of 3 or more, anatomical polytrauma (AIS of 3 or more in 2 or more body regions), and road traffic injury mechanism. Older age, low fall, increasing Charlson comorbidity scores, new injury severity score, and head and neck AIS of 3 or more were associated with worse function at 12 months compared to 6 months. ISS and revised trauma score were not significant predictors on univariate or multivariable analysis.

On multivariable ordinal regression, motor vehicle mechanism (OR 2.78, 1.51–5.12, p = 0.001) was associated with improved function, while male gender (OR 1.36, 95% CI 1.02–1.82, p = 0.039) predicted improved function at 12 months.

Conclusions

Females experience worse functional outcomes at 12 months, potentially due to majority of female injuries being low falls in the elderly. In contrast, motor vehicle injury patients had better functional outcomes at 12 months. Additional interventional strategies for high-risk groups should be explored.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Trauma is a cause of chronic morbidity and disability [1]. Trauma survivors may suffer from activity limitations, reduced or inability to work in addition to other participation restrictions [1,2,3,4]. Socio-economic consequences are often present [3, 5, 6]. There are several scales that are available to measure quality of life in trauma survivors but few studies have tracked longitudinal changes in functional outcome over time. Glasgow Outcome Scale-Extended (GOSE) is a measure of overall disability, originally used to assess global outcome in traumatic brain injury survivors, and also used for overall outcomes for trauma survivors [7,8,9,10,11,12]. Recovery trajectories may differ based on patient characteristics and other factors [10, 12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23]. Outcomes have also been known to vary depending on healthcare system [22, 24,25,26,27]. Routine registry data can help provide a good reflection of trauma outcomes [8, 11, 23, 28,29,30].

In Singapore, trauma is the leading cause for hospitalisation, and one of the major causes of mortality [31]. Using the registry information from the Singapore National Trauma Registry, established in 2011, we aimed to evaluate factors associated with improvement in function, measured by change in GOSE score at 12 months post-trauma, for blunt trauma survivors with severe injuries. The secondary aim was to compare the characteristics of responders to non-responders, given that our registry GOSE scores are generally obtained during office hours.

Methods

Data source and data collection

A retrospective multi-centre cohort study was conducted using the Singapore National Trauma Registry data. It covered all patients admitted via the emergency department in all public-sector hospitals in Singapore from the year 2011 to 2013, regardless of nationality. Details of the registry data collection and processing have been described [32, 33].

GOSE scoring was conducted using the standardised structured interview via telephone call during office hours by registry officials unrelated to the study as part of the routine registry data collection process. This included indirect methods to interview patient caregivers, as direct interview with all patients was impracticable [13, 34]. The GOSE has been validated for administration via proxy or direct interview with the patient [35], with no difference when administered via telephone or otherwise [36, 37].

GOSE scoring was either performed face-to-face (if patients were still warded at the acute hospital at the time), or by phone. Consent for the GOSE scoring was obtained prior to proceeding with the scoring questions. The phone numbers were obtained from hospital records, which contain both home and cell phone numbers. In the event that the telephone call did not get through, another attempt was done at a separate time and day, for up to five separate occasions before a “missing” entry made.

Study design

Retrospective data from January 2011 to December 2013 was extracted. The association between change in GOSE scores and patient, injury, and clinical factors was examined.

Study population

We included adult patients (age 18 years and older) who sustained blunt injuries based on International Classification of Diseases, ninth revision, diagnostic codes 800–959.9, excluding 905–909.9. As the Singapore NTR only contains GOSE outcome data for patients with at least injury severity score (ISS) of 16, no data was available for those with ISS < 16 [38]. Patients with missing GOSE scores at either timepoint for the primary analysis were also excluded.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measure was change in function at 12 months, compared to 6 months post-trauma. We measured and compared the GOSE score at 6 months and 12 months. These were categorised as similar (no change in scores), improved (increased), or worse (decreased) score at 12 months relative to the 6 month score.

Covariates

We extracted patient demographics and injury details (mechanism and severity) from the trauma registry.

Patient demographics were age, gender, and pre-injury employment status. Pre-injury employment status was a binary variable defined as “employed” or “unemployed”. Patient comorbidity was measured using the Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) [39].

Injury mechanisms were coded in the registry as motor vehicle accident, fall, interpersonal violence, machinery, tools/objects, sports, unknown and others. We re-categorised injury mechanisms as ‘low fall’ (equivalent to falls from standing, chair or bed), [33, 40] ‘high fall’ (falls from heights greater than 0.5 m) [33, 40], ‘road traffic’ (motor vehicle accident, pedestrian, and motorcycle injuries), and ‘others’.

We measured injury severity using the ISS, New Injury Severity Score (NISS) [26], Revised Trauma Score (RTS) [41]. The pattern of injury was described using an Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS) score of 3 or greater at each AIS region [42].

Statistical testing

Patient characteristics at baseline were summarised by mean (standard deviation), median (inter-quartile range), or frequency (%) as appropriate. Univariate comparisons between change in GOSE scores and predictors of interest was conducted using two-sample t tests or Mann-Whitney tests as appropriate, and chi-square tests, depending on variable type.

A multivariable ordinal regression model was fit to analyse patient group differences between those with similar/improved GOSE scores, and those with worse scores. Variables identified as having statistically significant associations (p < 0.05) in the univariate regression were included. Variables not statistically significant but deemed clinically meaningful were also included.

For the secondary analysis, we compared patient group differences between those without GOSE scores (non-responders to the registry calls), and those with GOSE scores (responders to registry calls). Univariate analysis using two-sample t tests or chi-square tests was conducted, depending on variable type.

STATA v.13 was used.

Ethical issues

Study and data collection protocols and processes were reviewed and approved by the respective hospital institutional review boards.

Results

Descriptive analysis

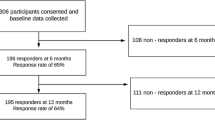

We identified 3013 potentially eligible patients from the registry and excluded 2072 as having no GOSE scores at all/non-responders to the telephone calls. Of the remaining 941 patients meeting the inclusion criteria, we further excluded 18 (1.9%) with missing 6-month GOSE scores and 445 (47.3%) with missing 12-month GOSE scores. Only 478 (50.8%) had complete GOSE scores at both 6-month and 12-month timepoints.

Of the 478 patients, compared to their 6-month score, one third had improved GOSE scores (n = 174, 36.4%), and 71 (14.9%) had worse GOSE scores at 12 months. The remainder (n = 233, 48.7%) had similar scores.

The mean age was 61.1 years, with males accounting for over two-thirds of the sample (n = 331, 69.2%). Majority were Singapore citizens or permanent residents (n = 418, 87.4%). Less than half were employed prior to their injury event (n = 225, 47.1%). The most common mechanism of injury was from low falls (n = 214, 44.8%). Majority had sustained head and neck injuries (n = 363, 75.9%). Summary statistics are presented in Table 1.

Univariate analysis

Functional outcomes at 12 months compared to 6 months were the same or better for male patients, or those who were employed prior to injury. Certain injuries and patterns were more likely to be associated with improved or similar functional outcomes: motor vehicle mechanism, those with injuries on the chest (AIS 3 or more), or patients with polytrauma (two or more body regions with AIS 3 or more). (Table 2, Fig. 1).

Older or higher comorbidity patients had worse functional outcomes. Severity scoring on NISS, head and neck injuries (AIS 3 or more), and injuries arising from low falls were predictors of worse function.

Injury scores ISS and RTS, other injury patterns or mechanisms were not significantly associated with functional outcomes.

Multivariable analysis

Male gender and injuries caused by motor vehicles were predictors of better outcome. All other variables (age, comorbidity, NISS), despite being significant on univariate analysis, were not significant on multivariable analysis (Table 2, Fig. 1).

Responder and non-responder comparison

Our response rate was 31.2% (n = 941), with 2072 non-responders to registry officials’ telephone calls (Table 3). Non-responders tended to be foreign nationals and were younger than responders. Comorbidity scores tended to be lower for non-responders, although injury scores were similar. More non-responders suffered from polytrauma.

Discussion

Our study is the first study of factors associated with functional outcomes in patients with severe blunt trauma injuries in Singapore. Overall improvement rates from 6 to 12 months in our study (36%) were higher than similar studies using trauma registry data in Australia (26%) [13]. Comparison with other studies was difficult due to differences in instruments used to measure functional outcome.

Similar to international literature, we found that male gender was associated with improved functional outcomes. This approach was supported by the literature, where the female gender has been identified with worse outcomes [13, 14, 18, 25]. However, this is potentially confounded by age-related injury epidemiology. Majority of male trauma survivors were young and were involved in high-velocity injury but had good outcome. Whereas majority of female injury was associated with age-related falls, thus having worse outcome [33, 43, 44].

Although not statistically significant, patients with older age and higher comorbidity were more likely to experience deterioration in function by 12 months [12,13,14,15, 17,18,19, 25, 45]. This may be related to reduced physiological reserve and frail pre-injury status, thereby negatively affecting recovery. The decline in function in older patients and those with significant comorbidities could be due to natural progression of chronic disease, in addition to the impact of the injury.

Intuitively, more severe injuries would lead to worse outcomes. However, we found that trauma survivors with higher NISS, a measure of injury severity, improved better. This is likely to arise from age-related confounder as previously mentioned, and it is supported by previous literature, where long-term outcome (mortality) was not affected by NISS.

We found pre-injury employment status to be a significant predictor of improved functional outcomes. We used employment as a proxy for pre-incident functioning and socio-economic status, both of which have been previously found to be positive prognostic factors for functional improvement [6, 12, 14, 18, 20]. However, this is also potentially affected by age.

We found similar relationship patterns between anatomical injuries and functional outcomes [18]. Patients with head and neck injuries had worse outcomes, ostensibly due to concomitant spinal cord or central nervous system injury. This highlights the importance of preventive or protective strategies. Polytrauma patients were also found to experience functional improvement over time, possibly representing patients with high-velocity polytrauma requiring longer recovery time but with good rehabilitation potential. This may also explain our findings in relation to NISS and gender.

Our study also described the real-world functional outcome registry experience if majority of staff force made the calls during office hours. Our response rate at 12 months was lower than that of other countries (US 42%, UK 43%, Hong Kong 59%, and Australia 85.8%) [28, 30, 45, 46]. Younger patients and foreign nationals were more likely to be non-responders [28]. We postulate that younger patients were more likely to have recovered and returned to daily activity, hence not responding to the calls [16]. Foreign nationals may have departed the country, thereby also not responding. Conversely, patients with low falls were more likely to respond. This may be due to the fact that low falls occur more commonly in older patients who are more likely to be available during office hours or who have companions with them to answer calls. This is similar to what the Victoria State Trauma registry experienced, where the older or institutional patients tended to be captured during office hours interviews, while younger and working adults tended to be non-responders during office hours as they were working and therefore unavailable [34].

Our study was limited to trauma registry data, representing only hospitalised patients. However, as our focus was on severe injuries, we expect the majority if not all such cases to require inpatient care. Our study was able to cover all public-sector institutions nationwide, accounting for 80% of all hospital-based care in an urban multi-ethnic population. We also had issues of responder bias, where patients lacked GOSE scores at later timepoints. Nevertheless, we were able to demonstrate target groups for intervention in order to improve functional outcomes and recovery trajectories. Future studies should focus on longer-term follow-up as recovery processes may extend beyond 12 months, and on interventional strategies, such as our recent study showing that patients discharged to inpatient rehabilitation services were less likely to be readmitted [40].

Conclusion

Females experience worse functional outcomes at 12 months, potentially due to majority of female injuries being low falls in the elderly. In contrast, motor vehicle injury patients had better functional outcomes at 12 months. Additional interventional strategies for high-risk groups should be explored [40].

Abbreviations

- AIS:

-

Abbreviated Injury Scale

- CCI:

-

Charlson comorbidity index

- GOSE:

-

Glasgow outcome scaled-extended

- ISS:

-

Injury Severity Score

- NISS:

-

New Injury Severity Score

- RTS:

-

Revised Trauma Score

References

Organization WH. Violence, injuries and disability: biennial report 2010–2011. 2012.

Soberg HL, Bautz-Holter E, Finset A, Roise O, Andelic N. Physical and mental health 10 years after multiple trauma: a prospective cohort study. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;78(3):628–33.

Soberg HL, Roise O, Bautz-Holter E, Finset A. Returning to work after severe multiple injuries: multidimensional functioning and the trajectory from injury to work at 5 years. J Trauma. 2011;71(2):425–34.

Evans JA, van Wessem KJ, McDougall D, Lee KA, Lyons T, Balogh ZJ. Epidemiology of traumatic deaths: comprehensive population-based assessment. World J Surg. 2010;34(1):158–63.

Hładki W, Lorkowski J, Trybus M, Brongel L, Kotela I, Golec E. Quality of life as a result of multiple injury in the aspect of limitations of handicaps--social roles. Przeglad lekarski. 2009;66(3):134–40.

Holbrook TL, Anderson JP, Sieber WJ, Browner D, Hoyt DB. Outcome after major trauma: 12-month and 18-month follow-up results from the trauma recovery project. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 1999;46(5):765–73.

Neugebauer E, Bouillon B, Bullinger M, Wood-Dauphinee S. Quality of life after multiple trauma--summary and recommendations of the consensus conference. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2002;20(3–4):161–7.

Gabbe BJ, Williamson OD, Cameron PA, Dowrick AS. Choosing outcome assessment instruments for trauma registries. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12(8):751–8.

Ardolino A, Sleat G, Willett K. Outcome measurements in major trauma--results of a consensus meeting. Injury. 2012;43(10):1662–6.

Gabbe BJ, Simpson PM, Sutherland AM, Wolfe R, Lyons RA, Cameron PA. Evaluating time points for measuring recovery after major trauma in adults. Ann Surg. 2013;257(1):166–72.

Williamson OD, Gabbe BJ, Sutherland AM, Wolfe R, Forbes AB, Cameron PA. Comparing the responsiveness of functional outcome assessment measures for trauma registries. J Trauma. 2011;71(1):63–8.

Gopinath B, Jagnoor J, Harris IA, Nicholas M, Casey P, Blyth F, et al. Prognostic indicators of social outcomes in persons who sustained an injury in a road traffic crash. Injury. 2015;46(5):909–17.

Gabbe BJ, Simpson PM, Harrison JE, Lyons RA, Ameratunga S, Ponsford J, et al. Return to work and functional outcomes after major trauma: who recovers, when, and how well? Ann Surg. 2016;263(4):623–32.

Polinder S, van Beeck EF, Essink-Bot ML, Toet H, Looman CW, Mulder S, et al. Functional outcome at 2.5, 5, 9, and 24 months after injury in the Netherlands. J Trauma. 2007;62(1):133–41.

Holtslag HR, van Beeck EF, Lindeman E, Leenen LP. Determinants of long-term functional consequences after major trauma. J Trauma. 2007;62(4):919–27.

Kaske S, Lefering R, Trentzsch H, Driessen A, Bouillon B, Maegele M, et al. Quality of life two years after severe trauma: a single centre evaluation. Injury. 2014;45:S100–S5.

Harcombe H, Langley J, Davie G, Derrett S. Functional status following injury: what recovery pathways do people follow? Injury. 2015;46(7):1275–80.

Gabbe BJ, Simpson PM, Cameron PA, Ponsford J, Lyons RA, et al. Long-term health status and trajectories of seriously injured patients: A population-based longitudinal study. PLoS Medicine. 2017;14(7):e1002322. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002322.

Gabbe BJ, Harrison JE, Lyons RA, Edwards ER, Cameron PA. Comparison of measures of comorbidity for predicting disability 12-months post-injury. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:30.

Gross T, Attenberger C, Huegli RW, Amsler F. Factors associated with reduced longer-term capacity to work in patients after polytrauma: a Swiss trauma center experience. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211(1):81–91.

Hoffman K, Cole E, Playford ED, Grill E, Soberg HL, Brohi K. Health outcome after major trauma: what are we measuring? PLoS One. 2014;9(7):e103082.

Dinh MM, Curtis K, Mitchell RJ, Bein KJ, Balogh ZJ, Seppelt I, et al. Major trauma mortality in rural and metropolitan NSW, 2009-2014: a retrospective analysis of trauma registry data. Med J Aust. 2016;205(9):403–7.

Balogh ZJ, Martin AB. Prospective cohorts and risk adjusted outcomes for trauma. Injury. 2010;41(Suppl 1):S24–6.

Celso B, Tepas J, Langland-Orban B, Pracht E, Papa L, Lottenberg L, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis comparing outcome of severely injured patients treated in trauma centers following the establishment of trauma systems. J Trauma. 2006;60(2):371–8 discussion 8.

Gabbe BJ, Simpson PM, Sutherland AM, Wolfe R, Fitzgerald MC, Judson R, et al. Improved functional outcomes for major trauma patients in a regionalized, inclusive trauma system. Ann Surg. 2012;255(6):1009–15.

Osler T, Baker SP, Long W. A modification of the injury severity score that both improves accuracy and simplifies scoring. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 1997;43(6):922–6.

Wong TH, Lumsdaine W, Hardy BM, Lee K, Balogh ZJ. The impact of specialist trauma service on major trauma mortality. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;74(3):780–4.

Rios-Diaz AJ, Herrera-Escobar JP, Lilley EJ, Appelson JR, Gabbe B, Brasel K, et al. Routine inclusion of long-term functional and patient-reported outcomes into trauma registries: the FORTE project. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017;83(1):97–104.

Gabbe BJ, Cameron PA, Hannaford AP, Sutherland AM, McNeil JJ. Routine follow up of major trauma patients from trauma registries: what are the outcomes? J Trauma. 2006;61(6):1393–9.

Rainer TH, Yeung HH, Gabbe BJ, Yuen KY, Ho HF, Kam CW, et al. A comparison of functional outcome in patients sustaining major trauma: a multicentre, prospective, international study. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e103396.

Singapore MoH. Singapore Health Facts 2017[updated 5 Dec 2017; cited 2018 23 July]. Available from: https://www.moh.gov.sg/resources-statistics.

Wong TH, Krishnaswamy G, Nadkarni NV, Nguyen HV, Lim GH, Bautista DCT, et al. Combining the new injury severity score with an anatomical polytrauma injury variable predicts mortality better than the new injury severity score and the injury severity score: a retrospective cohort study. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2016;24(1):25.

Wong TH, Nguyen HV, Chiu MT, Chow KY, Ong MEH, et al. The Low Fall as a Surrogate Marker of Frailty Predicts Long-Term Mortality in Older Trauma Patients. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(9):e0137127. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0137127.

Gabbe BJ, Sutherland AM, Hart MJ, Cameron PA. Population-based capture of long-term functional and quality of life outcomes after major trauma: the experiences of the Victorian state trauma registry. J Trauma. 2010;69(3):532–6 discussion 6.

Wilson JT, Pettigrew LE, Teasdale GM. Structured interviews for the Glasgow outcome scale and the extended Glasgow outcome scale: guidelines for their use. J Neurotrauma. 1998;15(8):573–85.

Pettigrew LE, Wilson JT, Teasdale GM. Reliability of ratings on the Glasgow outcome scales from in-person and telephone structured interviews. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2003;18(3):252–8.

McMillan T, Wilson L, Ponsford J, Levin H, Teasdale G, Bond M. The Glasgow outcome scale — 40 years of application and refinement. Nat Rev Neurol. 2016;12:477.

Baker SP, O’Neill B. The injury severity score: An update. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 1976;16(11):882–5.

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–83.

Wong TH, Wong YJ, Lau ZY, Nadkarni N, Lim GH, Seow DCC, et al. Not all falls are equal: risk factors for unplanned readmission in older patients after moderate and severe injury—a National Cohort Study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2018.08.006.

Champion HR, Sacco WJ, Copes WS, Gann DS, Gennarelli TA, Flanagan ME. A revision of the trauma score. J Trauma. 1989;29(5):623–9.

Gennarelli TA, Wodzin E. Abbreviated injury scale 2005: update 2008: Russ Reeder; 2008.

Haider AH, Crompton JG, Oyetunji T, Stevens KA, Efron DT, Kieninger AN, et al. Females have fewer complications and lower mortality following trauma than similarly injured males: a risk adjusted analysis of adults in the National Trauma Data Bank. Surgery. 2009;146(2):308–15.

James MK, Victor MC, Saghir SM, Gentile PA. Characterization of fall patients: does age matter? J Saf Res. 2018;64:83–92.

Rainer TH, Yeung JH, Cheung SK, Yuen YK, Poon WS, Ho HF, et al. Assessment of quality of life and functional outcome in patients sustaining moderate and major trauma: a multicentre, prospective cohort study. Injury. 2014;45(5):902–9.

Ahmed W, Alwe R, Wade D. One-year functional outcomes following major trauma: experience of a UK level 1 major trauma centre. Clin Rehabil. 2017;31(12):1646–52.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the National Trauma Committee, the National Trauma Registry working group, the National Trauma Unit, the trauma database coordinators, and colleagues at the National Registry of Diseases Office for maintaining the NTR. The collection and management of data for the National Trauma Registry is funded by the Ministry of Health, Singapore.

Funding

The authors received no specific individual funding for this work. The collection and management of data for the National Trauma Registry is funded by the Ministry of Health, Singapore.

Availability of data and materials

The data was obtained from a third party, the National Trauma Registry, established by Singapore’s Ministry of Health. Data are available from the National Registry of Diseases Office in Singapore for researchers who meet the criteria for access to confidential data. Details are available at https://www.nrdo.gov.sg/data-request/faq.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

THW conceived and designed the study. THW and NN performed the data analysis. ALT drafted the initial manuscript with all authors contributing substantially to the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. THW takes responsibility for the paper as a whole.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was given by the first author’s (Singapore General Hospital) Institutional Review Board and all data was de-identified and analysed on password-protected computers. Consent was not obtained because information was anonymized and de-identified prior to analysis as per National Registry of Diseases Office protocol.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Tan, A.L., Chiong, Y., Nadkarni, N. et al. Predictors of Change in Functional Outcome at six months and twelve months after Severe Injury: A Retrospective Cohort Study. World J Emerg Surg 13, 57 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13017-018-0217-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13017-018-0217-y