Abstract

Purpose

Pathogenesis of brain metastases/meningeal cancer and the emotional and neurological outcomes are not yet well understood. The hypothesis of our study is that patients with leptomeningeal cancer show volumetric differences in brain substructures compared to patients with cerebral metastases.

Methods

Three groups consisting of female breast cancer patients prior to brain radiotherapy were compared. Leptomeningeal cancer patients (LMC Group), oligometastatic patients (1–3 brain metastases) prior to radiosurgery (OMRS Group) and patients prior to whole brain radiation (WB Group) were included. All patients had MRI imaging before treatment. T1 MRI sequences were segmented using automatic segmentation. For each patient, 14 bilateral and 11 central/median subcortical structures were tested. Overall 1127 structures were analyzed and compared between groups using age matched two-sided t-tests.

Results

The average age of patients in the OMRS group was 60.8 years (± 14.7), 65.3 (± 10.3) in the LMC group and 62.6 (± 10.2) in the WB group. LMC patients showed a significantly larger fourth ventricle compared to OMRS (p = 0.001) and WB (p = 0.003). The central corpus callosum appeared smaller in the LMC group (LMC vs OMRS p = 0.01; LMC vs WB p = 0.026). The right amygdala in the WB group appeared larger compared with the OMRS (p = 0.035).

Conclusions

Differences in the size of brain substructures of the three groups were found. The results appear promising and should be taken into account for further prospective studies also involving healthy controls. The volumetrically determined size of the fourth ventricle might be a helpful diagnostic marker in the future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Brain metastases (BM) are the most common intracranial tumors in adults affecting 20 to 40% of all cancer patients [1,2,3]. BM occur in about 5% of patients with breast cancer (BC) at some point in the course of their disease [4,5,6]. The one-year survival rate of patients with parenchymal BM is about 50% [7]. Prospective trials have helped to guide treatment decisions for BM [8] and retrospective reviews have identified factors such as number of metastases, the presence or absence of active systemic disease, and hormone receptor status as having an impact on survival [9, 10].

Leptomeningeal cancer (LMC) is a rare, but often devastating form of tumor spread [5, 11]. The most common solid tumors leading to LMC are BC and lung cancer [12,13,14]. In particular women with invasive lobular carcinoma of the breast have a predilection to metastasize to the leptomeninges [15,16,17]. LMC patients can present a broad range of symptoms due to the involvement of multiple areas of the craniospinal axis. Diagnosis often requires a high index of suspicion and is confirmed by neuroimaging and cerebrospinal fluid analysis. Coexisting BM are present in 50 to 80% of LMC patients [14, 18,19,20,21]. Despite improvements in the treatment of BC, outcomes of BM and especially LMC remain unsatisfactory. An analysis of 36 studies including 851 patients reports a median survival of BC patients with LMC of 15 weeks [22], the 1-year survival varies from 7 to 24% [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31].

Despite the devastating prognosis, the intrinsic brain changes and pathogenesis of LMC/BM are not yet well understood. The aim of our study was to compare volumetric differences in brain substructures of breast cancer patients with oligo−/multiple parenchymal brain metastases/LMC.

Material and methods

We selected breast cancer patients treated between 2011 and 2017 for leptomeningeal cancer and parenchymal brain metastasis from our database. All institutional guidelines were followed. Informed consent was obtained from all patients. Bavarian state law (Bayrisches Krankenhausgesetz §27 Abs. 4 Datenschutz) allows the retrospective use of patient imaging data for research and publication, provided that any personal related data are kept anonymous. No patient received cranial radiotherapy or surgery prior to the treatment. Thirty age matched patients (10 in each group) were included in this retrospective analysis. To minimize heterogeneity within groups, due to gender differences in brain volume, only female patients were included in this study.

The three groups were:

-

leptomeningeal cancer patients (LMC group)

-

oligometastasic patients (1–3 brain metastases) (oligometastatic radiosurgery group – OMRS group) and

-

multiple metastatic brain patients (whole brain group – WB group).

Table 1 depicts the patients’ characteristics including age, luminal stage and Karnofsky Index.

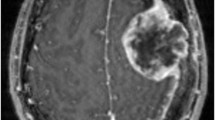

This retrospective study was approved by the Local Ethics Committee. All patients received magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in a supine position before treatment. Data acquisition was performed on a 3 T MR scanner (Magnetom Verio, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) with a 32-channel head coil array. The scanning protocol included a T1-weighted 3D magnetization rapid-acquisition gradient echo (MP-RAGE) acquired in an axial orientation. The T1- weighted images were transformed from the DICOM to NRRD file format by creating an nhdr header file for each subject. Cortical thickness analysis was performed using FreeSurfer version 5.3 (Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, Charlestown, MA, USA). Cortical reconstruction and volumetric segmentation were performed with the FreeSurfer image analysis suite (http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/). The technical details of these procedures are described elsewhere [32, 33]. The images were aligned to a common atlas and the grayscale intensity was normalized and corrected for inhomogeneity of the magnetic field. All voxels were labeled as gray matter, white matter or cerebral spinal fluid and the gray matter surface (pial) and white matter surface were created. The deep grey matter in each hemisphere was segmented into seven subcortical structures. Cortical surface was parcellated into discrete units based on gyral and sulcal anatomy (Fig. 1). In case of segmentation inaccuracies, e.g. caused by edema or lesions close to structural borders such as grey/white matter, manual correction was performed. Two out of thirty scans required manual correction. In all other cases FreeSurfer performed well and labelled even small BMs as “area of unknown origin”.

Using this approach none of the structures had to be excluded. A detailed list of all structures analyzed is provided in the Table 2. Statistical analyses were performed in SPSS 22 (SPSS, Chicago, IL). Overall 1127 structures were analyzed and compared within the three groups using age matched two-sided t-tests: When performing the two - sided t-test between groups (e.g.: LMC compared to OMRS) every patient in one group (e.g.: LMC) was matched by age to one person of the other group (e.g.: OMRS). Corresponding surface analyses were performed for each hemisphere. Results were adjusted with the Bonferroni correction for multiple region comparisons (P < 0.001 after correction was considered statistically significant).

Results

The average age in the OMRS group was 60.8 years (± 14.7), 65.3 (± 10.3) in the LMC group and 62.6 (± 10.2) in the WB group.

All analyzed structures are available in the Table 2. It shall be noted that after Bonferroni correction the results for the fourth ventricle remained statistical significant. Other findings have to be interpreted with caution, as these may have occurred due to chance.

In the LMC group several analyzed subcortical structures showed an increased size in comparison to either the OMRS and/or WB group. LMC patients showed a significantly larger fourth ventricle compared to both the OMRS and WB group. Further, the central corpus callosum was significantly smaller compared to both, the OMRS and the WB group. The right hippocampal volume and the right choroid plexus were also significantly increased in LMC as compared to the OMRS group.

Looking at the subcortical structures of the OMRS group the central corpus callosum was shown to be significantly larger in comparison with the LMC group.

The WB group showed an increased size in several subcortical substructures in comparison with the LMC and/or OMRS group: the central corpus callosum, the mid posterior part of the central corpus callosum, the left thalamus and the right putamen were significantly larger compared with the LMC group. Furthermore, the right amygdala showed an increased size compared with the OMRS group.

All significant differences amongst groups are depicted in Fig. 2.

Discussion

Image segmentation is often the first step in clinical applications. It is commonly used for measuring and visualizing the brain’s anatomical structures, for analyzing brain changes, for delineating pathological regions and for surgical planning and image-guided interventions.

This is the first study to evaluate volumetric neuroanatomical differences in the gray and white matter of BC patients. We found several differences between groups of differing forms of metastatic spread.

The LMC group showed an increased size of the fourth ventricle compared to the WB and OMRS groups. According to DeAngelis et al. leptomeningeal cancer invades the base of the brain and occludes the cerebrospinal fluid outflow of the fourth ventricle. Further, the meningeal tumor and its accompanying inflammatory response also reduce the cerebrospinal fluid absorption. Thus, intracranial pressure is slowly elevated and may result in ventricular dilatation [34]. Jung et al. have shown that surgically treating hydrocephalus in patients with leptomeningeal cancer can improve the overall survival [35]. Brain segmentation, as demonstrated by our study, point out the ventricular dilatation and could be used in a clinical setting to identify early hydrocephalus in leptomeningeal cancer patients and potentially improve patients’ prognosis. Leptomeningeal cancer can be difficult to prove. Often several biopsies are needed, in order to detect tumor cells in the cytology. In this study, 4 out of ten patients in the LMC group received cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) puncture. Out of these 4 patients, 2 had tumor cells in their CSF. All other patients were diagnosed by cranial MRI imaging and neurological symptoms. An enlarged fourth ventricle, as shown by our study, may provide another diagnostic tool of leptomeningeal cancer, especially in cases with negative liquor cytology.

The central corpus callosum, which connects the left and right cerebral hemispheres, was found to be significantly smaller in the LMC group compared with the WB and OMRS groups. Research using mice with either meningeal overgrowth or selective loss of meninges, has identified a cascade of morphogenic signals initiated by the meninges that regulates corpus callosum development. BMP7, produced either by overexpression in the medial cortical wall or by hyperplastic meninges, is sufficient to cause callosal agenesis [36]. This suggests a link between leptomeningeal cancer leading to an overexpression of certain signals and the decreasing size of the central corpus callosum. In addition, more research is starting to link corpus callosum decline to cognitive decline. A study on cognitive impairment in MS patients states “Corpus callosum atrophy predicts a clinically meaningful cognitive decline, … “[37]. Similarly, other studies on bipolar disorder and suicidal vulnerability as well as major depression and dementia are pointing to corpus callosum volume decrease, playing a central role in neurocognitive dysfunction [38,39,40].. Hence, corpus callosum atrophy may be hold responsible for the quick cognitive decline in leptomeningeal cancer patients and should be addressed further by future research on clinical manifestations of leptomeningeal cancer. However, it needs to be noted that degeneration of corpus callosum in MS and dementia is a long lasting atrophic process. Rapid decrease of corpus callosum in LMC patients appears somewhat peculiar and could also be related to raised intracranial pressure.

The right amygdala, which has a direct correlation with negative emotions, especially fear and sadness, was shown to be larger in the WB group in comparison with the OMRS group [41]. Although serious depression is not seen in the majority of breast cancer patients and survivors, many experience treatment-related distress and fear of recurrence [42]. Earlier studies have shown that psychosocial stress can affect inflammatory processes that have important consequences for cancer outcomes [43, 44]. Muscatell et al. reported a strong, positive correlation between circulating inflammatory markers concentration in response to stress and amygdala activity [45, 46]. The increased size of the right amygdala can be interpreted as an increased stress reaction and /or inflammatory response reaction and could be limited with psychological interference [47, 48]. Although these findings might suggest higher anxiety levels in LMC patients it is very difficult to interpret these results in absence of a healthy control group.

Our results showed an increased volume of the right hippocampus in the LMC group in comparison with the OMRS group. Research investigating the hippocampus, which is involved in creating and organizing new memories, has shown that morphologic differences exist between the right and left hippocampus in animal testing [49]. Research on the individual role of the right and left hippocampus is not yet conclusive, but should be performed, especially when WBRT with hippocampal sparing is on its way as a new and promising treatment.

The right choroid plexus was significantly increased in the LMC group in comparison with the OMRS group. The choroid plexus is a plexus of cells that produces the cerebrospinal fluid in the ventricles of the brain [50]. So far, a distinction between the different parts of the choroid plexus in brains of patients with metastases has not been investigated.

The left thalamus and the right putamen in the WB group were also significantly larger compared to the LMC group. The thalamus has several functions such as relaying sensory signals and the regulation of consciousness, sleep, and alertness. Studies investigating language deficiencies have shown that the right and left Thalamus are not functionally equivalent [51]. A connection between differing thalamus sizes of the two hemispheres and the occurrence of meningeal cancer has not been examined.

The primary function of the putamen is to regulate movements and influence various types of learning. Using MRI of 98 individuals (male and female) of various ages no hemispherical asymmetry in putamen volume has been found [52].

As of today, our knowledge concerning hemispherical differences of subcortical structures such as the hippocampus, the choroid plexus, the thalamus and the putamen is not sufficient to discuss and formulate perfect explanation to our results. The right hippocampus and the right plexus choroid showed an increase in size in group LMC compared to OMRS. Also, the right amygdala showed an increase in group WBR compared to group OMRS. Yet these are only observations with no sufficient data to support a hypothesis.

It has to be noted, that our results have to be interpreted cautiously in absence of an age matched healthy control group that would be helpful to define values as abnormal and to draw conclusions on effects of LMC and BM on size of brain structures.It is important to understand that our findings concerning the right hippocampus, left thalamus and right putamen should be interpreted with caution and might be due to artefacts. Nonetheless, it would be extremely interesting to validate these results by comparing it to a healthy control. Our sample size was small and the data was cross-sectional. As such it is unclear if the relation between volumetric neuroanatomical differences was present prior to cancer diagnosis or resulted from the cranial cancer manifestation. Future studies will need larger samples and an experimental longitudinal design.

Conclusions

Several differences in size of the brain substructures were found. Most significantly fourth ventricle was enlarged in LMC, which might aid the diagnosis of LMC in the futureSize differences of corpus callosum and choroid plexus might also be related to direct or indirect effects of LMC.Differences in size of amygdala, thalamus, putamen and hippocampus need to be further validated in comparison to healthy control groups to better evaluate possible disease related effects on separate brain structures.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Part of the data was presented in October at the annual meeting of the American society of Radiation Oncology (ASTRO 2018) - accepted abstract no. MO_11_2559; Track: Central Nervous System.

Abbreviations

- BM:

-

Brain metastases

- CN :

-

Caudate nucleus

- GP:

-

Globus pallidus

- LM:

-

Leptomeningeal metastasis

- LMC Group:

-

Leptomeningeal cancer patients

- OMRS Group:

-

Oligometastasic patients prior to radiosurgery

- PT:

-

Putamen

- TH:

-

Thalamus

- WB Group:

-

Whole brain group

References

Posner JB, Chernik NL. Intracranial metastases from systemic cancer. Adv Neurol. 1978;19:579–92.

Schiff D. Single brain metastasis. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2001;3(1):89–99.

van den Bent MJ. The diagnosis and management of brain metastases. Curr Opin Neurol. 2001;14(6):717–23.

Barnholtz-Sloan JS, et al. Incidence proportions of brain metastases in patients diagnosed (1973 to 2001) in the metropolitan detroit cancer surveillance system. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(14):2865–72.

Kim HJ, et al. Clinical outcome of central nervous system metastases from breast cancer: differences in survival depending on systemic treatment. J Neuro-Oncol. 2012;106(2):303–13.

Pestalozzi BC, et al. Identifying breast cancer patients at risk for central nervous system (CNS) metastases in trials of the international breast Cancer study group (IBCSG). Ann Oncol. 2006;17(6):935–44.

Engel J, et al. Determinants and prognoses of locoregional and distant progression in breast cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;55(5):1186–95.

Tsao MN, et al. Radiotherapeutic and surgical management for newly diagnosed brain metastasis (es): an American Society for Radiation Oncology evidence-based guideline. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2012;2(3):210–25.

Dawood S, et al. Defining prognosis for women with breast cancer and CNS metastases by HER2 status. Ann Oncol. 2008;19(7):1242–8.

Slimane K, et al. Risk factors for brain relapse in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2004;15(11):1640–4.

Harwood AR, Simson WJ. Radiation therapy of cerebral metastases: a randomized prospective clinical trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1977;2(11–12):1091–4.

Kesari S, Batchelor TT. Leptomeningeal metastases. Neurol Clin. 2003;21(1):25–66.

Kaplan JG, et al. Leptomeningeal metastases: comparison of clinical features and laboratory data of solid tumors, lymphomas and leukemias. J Neuro-Oncol. 1990;9(3):225–9.

Clarke JL, et al. Leptomeningeal metastases in the MRI era. Neurology. 2010;74(18):1449–54.

Lamovec J, Zidar A. Association of leptomeningeal carcinomatosis in carcinoma of the breast with infiltrating lobular carcinoma. An autopsy study. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1991;115(5):507–10.

Lamovec J, Bracko M. Metastatic pattern of infiltrating lobular carcinoma of the breast: an autopsy study. J Surg Oncol. 1991;48(1):28–33.

Altundag K, et al. Clinicopathologic characteristics and prognostic factors in 420 metastatic breast cancer patients with central nervous system metastasis. Cancer. 2007;110(12):2640–7.

Umemura S, et al. Clinical outcome in patients with leptomeningeal metastasis from non-small cell lung cancer: Okayama lung Cancer study group. Lung Cancer. 2012;77(1):134–9.

Raizer JJ, et al. Brain and leptomeningeal metastases from cutaneous melanoma: survival outcomes based on clinical features. Neuro-Oncology. 2008;10(2):199–207.

Morris PG, et al. Leptomeningeal metastasis from non-small cell lung cancer: survival and the impact of whole brain radiotherapy. J Thorac Oncol. 2012;7(2):382–5.

Lara-Medina F, et al. Clinical features and prognostic factors in patients with carcinomatous meningitis secondary to breast cancer. Breast J. 2012;18(3):233–41.

Scott BJ, Oberheim-Bush NA, Kesari S. Leptomeningeal metastasis in breast cancer - a systematic review. Oncotarget. 2016;7(4):3740–7.

Wasserstrom WR, Glass JP, Posner JB. Diagnosis and treatment of leptomeningeal metastases from solid tumors: experience with 90 patients. Cancer. 1982;49(4):759–72.

Rudnicka H, Niwinska A, Murawska M. Breast cancer leptomeningeal metastasis--the role of multimodality treatment. J Neuro-Oncol. 2007;84(1):57–62.

Le Rhun E, et al. A retrospective case series of 103 consecutive patients with leptomeningeal metastasis and breast cancer. J Neuro-Oncol. 2013;113(1):83–92.

Le Rhun E, Taillibert S, Chamberlain MC. Carcinomatous meningitis: leptomeningeal metastases in solid tumors. Surg Neurol Int. 2013;4(Suppl 4):S265–88.

Krex D, et al. Long-term survival with glioblastoma multiforme. Brain. 2007;130(Pt 10:2596–606.

Hyun JW, et al. Leptomeningeal metastasis: clinical experience of 519 cases. Eur J Cancer. 2016;56:107–14.

Petithuguenin Gauthier H, et al. Survival of breast cancers patients with meningeal carcinoma. Bull Cancer. 2011;98(4):391–8.

Fizazi K, et al. Meningeal carcinomatosis in patients with breast carcinoma. Clinical features, prognostic factors, and results of a high-dose intrathecal methotrexate regimen. Cancer. 1996;77(7):1315–23.

de Azevedo CR, et al. Meningeal carcinomatosis in breast cancer: prognostic factors and outcome. J Neuro-Oncol. 2011;104(2):565–72.

Fischl B, Sereno MI, Dale AM. Cortical surface-based analysis. II: inflation, flattening, and a surface-based coordinate system. Neuroimage. 1999;9(2):195–207.

Fischl B, et al. Whole brain segmentation: automated labeling of neuroanatomical structures in the human brain. Neuron. 2002;33(3):341–55.

DeAngelis LM, Posner JB, Posner JB. Neurologic complications of cancer. In: Contemporary neurology series, vol. xv. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2009. p. 634.

Jung TY, Chung WK, Oh IJ. The prognostic significance of surgically treated hydrocephalus in leptomeningeal metastases. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2014;119:80–3.

Choe Y, Siegenthaler JA, Pleasure SJ. A cascade of morphogenic signaling initiated by the meninges controls corpus callosum formation. Neuron. 2012;73(4):698–712.

Papathanasiou A, et al. Corpus callosum atrophy as a marker of clinically meaningful cognitive decline in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. Impact on employment status. J Clin Neurosci. 2017;43:170–5.

Frederiksen KS. Corpus callosum in aging and dementia. Dan Med J. 2013;60(10):B4721.

Gifuni AJ, et al. Corpus callosum volumes in bipolar disorders and suicidal vulnerability. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. 2017;262:47–54.

Matsuoka K, et al. Microstructural differences in the Corpus callosum in patients with bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78(1):99–104.

Rasia-Filho AA, Londero RG, Achaval M. Functional activities of the amygdala: an overview. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2000;25(1):14–23.

Ganz PA. Psychological and social aspects of breast cancer. Oncology (Williston Park). 2008;22(6):642–6 650; discussion 650, 653.

Pomykala KL, et al. The association between pro-inflammatory cytokines, regional cerebral metabolism, and cognitive complaints following adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. Brain Imaging Behav. 2013;7(4):511–23.

Bower JE, Lamkin DM. Inflammation and cancer-related fatigue: mechanisms, contributing factors, and treatment implications. Brain Behav Immun. 2013;30(Suppl):S48–57.

Muscatell KA, et al. Links between inflammation, amygdala reactivity, and social support in breast cancer survivors. Brain Behav Immun. 2016;53:34–8.

Muscatell KA, et al. Greater amygdala activity and dorsomedial prefrontal-amygdala coupling are associated with enhanced inflammatory responses to stress. Brain Behav Immun. 2015;43:46–53.

Holzel BK, et al. Stress reduction correlates with structural changes in the amygdala. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2010;5(1):11–7.

Taren AA, et al. Mindfulness meditation training alters stress-related amygdala resting state functional connectivity: a randomized controlled trial. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2015;10(12):1758–68.

Diamond MC, et al. Age-related morphologic differences in the rat cerebral cortex and hippocampus: male-female; right-left. Exp Neurol. 1983;81(1):1–13.

Strazielle N, Ghersi-Egea JF. Choroid plexus in the central nervous system: biology and physiopathology. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2000;59(7):561–74.

Ojemann GA. Asymmetric function of the thalamus in man. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1977;299:380–96.

Halkur Shankar S, Ballal S, Shubha R. Study of normal volumetric variation in the putamen with age and sex using magnetic resonance imaging. Clin Anat. 2017;30(4):461–6.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: MND. Performed the experiments: MM; AR; MND. Analyzed the data: MM, AR, KJB, JE, JJW, SEC, MO, MND. Wrote the paper: MM, AR, KJB, MO, MND. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All institutional guidelines were followed. Informed consent was obtained from all patients. According to local regulations, the bavarian state law (Bayrisches Krankenhausgesetz §27 Abs. 4 Datenschutz) allows the retrospective use of patient imaging data for research and publication, provided that any personal related data are kept anonymous.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

S.E. Combs: Advisory Boards/Advisor: BMS, Astra Zeneca, Roche, Novocure, Daiichi Sankyo, Icotec; Speakers Honoraria: BMS, Astra Zeneca, Roche, Novocure, Daiichi Sankyo, Icotec, Brainlab, varian, Accuray, Zeiss Meditec, Dr. Sennewald, Elekta, Merck Darmstadt, Medac. The rest of the authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Mayinger, M., Reibelt, A., Borm, K.J. et al. MRI based neuroanatomical segmentation in breast cancer patients: leptomeningeal carcinomatosis vs. oligometastatic brain disease vs. multimetastastic brain disease. Radiat Oncol 14, 170 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13014-019-1380-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13014-019-1380-3