Abstract

Background

Radiation or radiochemotherapy is a common adjuvant therapy for gastric cancer. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) has been demonstrated to provide better dose conformity, allowing dose escalation and/or reduction of normal tissue exposure compared with three-dimensional conformal radiation treatment (3D-CRT). However, the efficacy of IMRT and 3D-CRT in gastric cancer remains controversial. This study aimed to compare the efficacy and safety of IMRT with those of 3D-CRT in treating patients with gastric cancer through conducting a meta-analysis of 3-year survival rates [overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS)], local control rates, and toxic event rates.

Methods

Embase, PubMed, the Cochrane Library, and clinical trial databases were searched to identify the clinical trials of IMRT versus 3D-CRT for treating patients with gastric cancer. The obtained data of survival and safety were analyzed using the Stata 14.0 software.

Results

A total of 9 controlled clinical studies, including 516 patients with gastric cancer, met the inclusion criteria and were included in this meta-analysis. The results of the meta-analysis showed that the 3-year OS rate was slightly higher in the IMRT group than in the 3D-CRT group, without any statistical significance. The 3-year local control rate was significantly higher in the IMRT group than in the 3D-CRT group. No significant difference in the 3-year DFS rate was found between the IMRT and 3D-CRT groups. Grade 2–4 toxicities were similar between the IMRT and 3D-CRT groups.

Conclusion

The findings suggested that IMRT might be superior to 3D-CRT in treating patients with gastric cancer in terms of local control rates without increasing toxicity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Gastric cancer is a major cause of cancer-associated mortality worldwide [1]. Nearly half of the worldwide gastric cancer cases and deaths occur in China [1, 2]. As reported by the GLOBOCAN 2012, approximately one million new gastric cancer cases and more than 700,000 cancer-related deaths occurred globally in 2012 [3]. The treatment strategy for gastric cancer is still controversial [4]. Surgical resection is preferred for patients without advanced-stage cancer [4]. On the contrary, the benefits of surgical resection for patients with locally advanced gastric cancer are limited [5,6,7,8]. Perioperative strategies and adjuvant therapies, such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy, chemoradiotherapy, and targeted therapy, have been used in clinical settings for years and proved to be effective [4, 9,10,11,12].

Several clinical studies demonstrated that adjuvant therapies administered after surgical resection prolonged the survival of patients with locally advanced gastric cancer [4, 10, 11, 13,14,15,16,17,18]. Adjuvant therapy, such as radiotherapy, significantly increased the survival of patients with gastric cancer and reduced the risk of recurrence [15, 17]. However, the therapeutic benefits were accompanied by increased adverse events or toxicity [17, 19].

The three-dimensional conformal radiation (3D-CRT) and intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) are gradually implemented in clinical studies to reduce radiation-related toxicity without the loss of treatment effectiveness. A previous study showed significant grade 3 toxicity in patients with resected gastric or gastroesophageal junction cancers treated with 3D-planned CRT [20]. In recent years, several clinical trials have been performed to evaluate clinical outcomes and toxicity in patients with resected gastric cancer treated with IMRT versus 3D-CRT [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. Minn et al. [29] compared the clinical efficacy and adverse events in patients with gastric cancer who received IMRT versus 3D-CRT. They did not find a significant difference between these two groups in terms of 2-year overall survival (OS) rate (P = 0.5). Whether IMRT was associated with reduced toxicity compared with 3D-CRT was explored by Liu et al. [26] who recruited 24 patients with stage IB–IIIB gastric cancer: 12 in the 3D-CRT group and 12 in the IMRT group. No significant differences in the OS and disease-free survival (DFS) rates were observed between 3D-CRT and IMRT, while similar toxicity was observed in these two groups. Due to the smaller sample size and nonsignificant differences observed in the aforementioned studies, this meta-analysis was performed to explore whether IMRT was more effective and safe compared with 3D-CRT in treating patients with gastric cancer.

Method

Search strategy

The electronic databases, including PubMed, Embase, and the Cochrane Library, were systematically searched using the following key words: gastric cancer, gastric carcinoma, stomach cancer, intensity-modulated radiotherapy, intensity-modulated radiation therapy, three-dimensional conformal radiation therapy, three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy, 3-dimensional conformal radiation therapy, IMRT, and 3D-CRT. The languages of the included studies were limited to English and/or Chinese. Relevant studies were manually retrieved if necessary. The details of the search strategy in PubMed are shown in Additional file 5: Data S1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria

The study eligibility criteria were as follows: (1) patients diagnosed with gastric cancer; (2) two comparison groups, one group receiving IMRT and the other group receiving 3D-CRT; and (3) follow-up time: ≥6 months.

The report eligibility criteria were as follows: (1) outcomes including OS, DFS, and toxicity; (2) randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or observational study; (3) language limited to Chinese and/or English; (4) study sample size more than 15 cases; and (5) published studies and meeting abstracts.

Exclusion criteria

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) review, case report, abstracts, and lectures; (2) patients lacking precise clinical diagnosis; (3) incorrect data or incomplete data that could not be extracted from other relevant data; and (4) repeated published studies. The studies were selected according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and the data were extracted from the context of the studied reports.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two independent investigators (FR and YZ) extracted the following essential information using a predesigned data extraction table that involved (1) general information, including the title, author, date of publication, and source of the study; (2) research characteristics, including general information regarding patients and interventions; and (3) survival rates, relapse rates, and toxicity in each group. The indicators of radiotherapy included PTV dose distribution, uniformity index (HI), average dose of normal liver (Dmean), and average dose of kidneys (Dmean). Discrepancies were discussed by these two reviewers. A third reviewer (YC) was consulted if any disagreement occurred. Inquiries to the original researchers were performed to collect additional or missing information.

The methodological quality of the studies was evaluated according to the quality evaluation criteria of RCTs detailed in the Cochrane System Reviewer’s Manual 5: (1) generation of random sequences; (2) allocation hiding; (3) blinding; (4) lost to follow-up and exiting; (5) selective reporting; and (6) other selective biases.

The study quality was assessed using the Newcastle–Ottawa scale (NOS). An NOS score ≥ 7 indicated high-quality studies [30, 31].

Statistical analysis

This meta-analysis was performed using the Stata 14.0 software (Stata Corp LLC). Appropriate statistical methods were used to analyze the differences in effectiveness and safety between the IMRT and 3D-CRT groups. The heterogeneity between the included studies was analyzed using the I2 test. If no heterogeneity was observed within studies (P > 0.1 and I2% < 50%), the fixed-effects model was applied for the analysis. Otherwise, the source of heterogeneity was detected using subgroup and meta-regression analyses. If statistical heterogeneity existed between studies without clinical heterogeneity, or if the difference was not clinically significant, the random-effects model was used for the analysis. The sensitivity analysis was applied to examine the stability of the meta-analysis results. Publication bias was assessed using funnel plots and Begg’s and Egger’s regression asymmetry tests [32, 33]. The risk ratio (RR) was used to present the dichotomous data, and the confidence interval (CI) was set to 95%. A difference with P value ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Results of literature research

A total of 168 studies were identified after comprehensively searching relevant databases and other sources. Twelve studies were excluded due to duplication. After reviewing the titles and abstracts, 119 studies were excluded for multiple reasons. Further, 28 additional studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded after reviewing full texts. Finally, two RCTs, one prospective study, and 6 retrospective studies [12, 22, 23, 25, 26, 29, 34,35,36], involving 516 patients, were included in this meta-analysis. Of these, eight trials [12, 22, 23, 25, 26, 29, 34, 36] compared the efficacy and toxicity of IMRT versus 3D-CRT in patients with resected gastric cancer. Two RCTs [22, 25] evaluated the efficacy and toxicity of postoperative IMRT versus 3D-CRT. The basic characteristics of the included studies are shown in Table 1, and the trial selection process is presented in Fig. 1.

General information and characteristics of the included studies

Patients and interventions

A total of 516 patients with gastric cancer participated in the eligible clinical trials. The IMRT group and the 3D-CRT group involved 236 and 239 patients, respectively. The age of all included patients ranged from 23 to 83 years. Most of the patients underwent surgical resection of gastric cancer. This radiotherapy was performed by clinical radiation oncologists, physicists, and technicians. The definitions and details of radiation fields were different among the included studies. A variety of radiation doses of IMRT and 3D-CRT were used in the studies for treating gastric cancer. The duration of radiation ranged from 5 to 6 weeks. Traditional supportive treatments and/or adjuvant chemotherapy were used for patients during radiotherapy in some studies. The baseline characteristics of the eligible studies are listed in Table 1.

Quality assessment of included studies

The overall methodological quality of all included studies was high. Two RCTs [22, 25] used random allocation hiding, and all reported cases lost to the follow-up. The quality assessment of the included studies is shown in Additional file 6: Table S1 and Additional file 7: Table S2.

Effectiveness of interventions

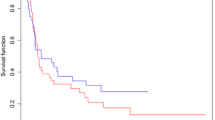

Overall survival

Six studies, including 352 patients, compared the OS rate of IMRT versus 3D-CRT in patients with gastric cancer. The heterogeneity test results were P = 0.942 and I2 = 0%, indicating a low risk of heterogeneity; the fixed-effects model was then used. The forest plots of the meta-analysis showed that patients with IMRT had a slightly better 3-year OS rate with an RR of 1.16, compared with patients with 3D-CRT (95% CI, 0.98–1.36) (Fig. 2) despite no statistical significance.

Two studies [12, 29] investigated the 2-year OS rate, while one study [34] reported the 5-year OS rate in patients with gastric cancer. The heterogeneity test results were P = 0.42 and I2% = 0%, showing no heterogeneity within studies. The results of the meta-analysis indicated that IMRT was associated with a significantly better 2-year OS rate with a pooled RR of 2.49 (95% CI, 1.18–5.25; P = 0.02) compared with 3D-CRT. The descriptive analysis of the 5-year OS rate was used due to the lack of enough data for combined analysis. Boda-Heggemann et al. [34] reported that the 5-year OS rate in the IMRT and 3D-CRT groups was 0.47 (18/38) and 0.26 (7/27), respectively.

Disease-free survival

As shown in Fig. 3, 5 studies, including 302 patients with gastric cancer, investigated the DFS rate after IMRT and 3DCRT. The 3-year DFS rate was similar in patients receiving IMRT and 3D-CRT, with no heterogeneity (P = 0.732; I2% = 0%). The administration of IMRT was not associated with an improvement in the DFS rate (RR = 1.16; 95% CI, 0.95–1.43; P > 0.05). Boda-Heggemann et al. [34] reported that the 5-year DFS rate in the IMRT and 3D-CRT groups was 0.44 (17/38) and 0.22 (6/27), respectively.

Loco-regional relapse rate

Four studies, including 218 patients, compared the loco-regional recurrence (LRR) rate in patients with gastric cancer after receiving IMRT versus 3D-CRT. The meta-analysis results showed statistically significant differences between the groups (RR = 0.62; 95% CI, 0.39–0.98; P < 0.05), indicating a decreased risk of 3-year LRR in the IMRT group compared with the 3D-CRT group (Fig. 4).

Quality of life

Goody et al. [35] reported the changes in the quality of life of patients with gastric cancer treated with IMRT versus 3D-CRT. The quality-of-life compliance ranged from 93% at baseline to 70% after 4 weeks of the treatment.

Toxicity

An overview of the toxicities reported in included trials is presented in Fig. 5. The validated definition of radiation-related toxicities was based mainly on the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group or Common Toxicity Criteria scales in these selected studies. Three studies [22, 35, 36] did not show detailed toxicity data for analysis.

Liver dysfunction, gastrointestinal (GI) toxicity, and kidney toxicity were reported in two studies, five studies, and two studies, respectively (Fig. 5). No significant differences in liver dysfunction, GI toxicity, and kidney toxicity were found in patients receiving postoperative IMRT compared with 3D-CRT. The RR for liver dysfunction, GI toxicity, and kidney toxicity was 0.5 (95% CI, 0.14–1.78), 1.04 (95% CI, 0.70–1.56), and 0.89 (95% CI, 0.28–2.80), respectively (Fig. 5).

Sensitivity analysis

A sensitivity analysis of all the four meta-analyzed outcomes (OS, DFS, LRR, and toxicity) was performed. Except for LRR, all the pooled results of the other three outcomes (OS, DFS, and toxicity) did not change significantly (Additional file 1: Figure S1, Additional file 2: Figure S2, Additional file 3: Figure S3, Additional file 4: Figure S4). The pooled LRR result changed after excluding the study by Boda-Heggemann et al. [34], indicating that this study weighted largely (66.75%).

Publication bias

The funnel plots and Egger’s and Begg’s tests were used to detect any publication bias. No significant evidence of publication bias in the meta-analysis of OS rate was found (Egger’s test: P = 0.684; Begg’s test: P = 0.707).

Discussion

This meta-analysis examined the impact of IMRT versus 3D-CRT in patients with resectable gastric cancer by quantitatively summarizing the findings from nine different trials. The results showed that the use of IMRT was associated with a nearly 40% reduction in the risk of disease relapse and a 16% increase in the OS rate. Moreover, the risk of radiation-related toxicities was not increased in IMRT compared with 3D-CRT. Taken together, IMRT seemed to be a promising alternative in this clinical setting.

A meta-analysis [16] assessed the impact of radiotherapy on both 3- and 5-year survival [overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS)] rates in patients with resectable gastric cancer by including 14 RCTs. The pooled result showed that the addition of radiotherapy after surgery improved the 3- (RR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.01–1.38) and 5-year OS and DFS rates (RR, 1.38; 95% CI, 1.18–1.61). IMRT was widely used in recent studies, demonstrating promising efficacy and less toxicity. Therefore, comparing the efficacy and toxicity of IMRT with those of 3D-CRT in patients with gastric cancer was necessary. The findings of this meta-analysis indicated a significant improvement in patient’s outcomes after IMRT compared with 3D-CRT. Notably, IMRT significantly reduced the risk of loco-regional relapse, indicating its high clinical efficacy and potential as first-line adjuvant treatment for locally advanced or high-risk gastric cancer.

Reducing radiation toxicity and improving treatment compliance and quality of life of patients are serious issues in clinical practice. This meta-analysis showed that patients in the IMRT group did not experience increased radiation-related side effects compared with those in the 3D-CRT group. Recent studies showed that IMRT had a lower incidence of toxicity, especially grade 3 and 4 toxicities, compared with 3D-CRT. Murthy et al. [37] showed that IMRT was more advantageous than 3D-CRT in terms of dose coverage and conformity. Ringash et al. [38] also reported that the conformity and uniformity of IMRT were better than those of 3D-CRT; it was better in reducing the dose of liver radiation, thus decreasing liver toxicity. In addition, Wei Gang et al. [39] also showed that the radiation field distribution, homogeneity, and conformity of IMRT were superior to those of 3D-CRT in reducing the normal tissue radiation dose. Wieland et al. [40] showed that the radiation dose of the kidney and liver was lower in the IMRT group than in the 3D-CRT group. The results were consistent with those of previous IMRT studies, which paved the way for IMRT as the stand-alone radiotherapy treatment for gastric cancer.

Although a strict retrieving and analysis strategy was used for a comprehensive meta-analysis, some limitations should be highlighted. First, the included studies had uneven quality and a limited number of participants; some of them were retrospective studies, increasing the risk of selective reporting bias. Second, the included studies were limited to Chinese and English databases, leading to language bias. Third, the heterogeneity of IMRT or 3D-CRT in different studies led to clinical heterogeneity and reduced the statistical power. Fourth, the survival data were not provided by different age and staging of patients with gastric cancer, particularly the lymph node status after resection. Therefore, it was not appropriate to analyze the impact of IMRT versus 3D-CRT on patient survival by age and tumor staging. Finally, the detail and radiation fields of radiotherapy varied among studies, leading to different toxicities and efficacy. The radiation dose of IMRT was higher than that of 3D-CRT in the study by Liu et al. [26], but severe toxicity was similar for the two. The present meta-analysis also showed similar toxicity for IMRT and 3D-CRT, which was consistent with previous findings. Despite the aforementioned limitations, the findings of this meta-analysis might guide adjuvant therapies for resected gastric cancer.

Conclusions

In summary, this meta-analysis showed that IMRT was associated with a slight increase in the 3-year OS rate and a significant increase in the local control rate, without affecting the DFS rate or increasing the clinical toxicity rate, compared with 3D-CRT. Further studies, such as more rigorous, high-quality RCTs, are required to validate the effectiveness of IMRT in treating gastric cancer. Moreover, a dose–response curve for the radiation dose and potential injuries at specific sites should be explored.

Abbreviations

- 3D-CRT:

-

Three-dimensional conformal radiation

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- GI:

-

Gastrointestinal

- IMRT:

-

Intensity-modulated radiation therapy

- NOS:

-

Newcastle–Ottawa scale

- RCTs:

-

Randomized controlled trials

- RR:

-

Risk ratio

References

Nie Y, Wu K, Yu J, Liang Q, Cai X, Shang Y, et al. A global burden of gastric cancer: the major impact of China. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017:1–11.

Sano T. Gastric cancer: Asia and the world. Gastric Cancer. 2017;20:1–2.

Park JY, von Karsa L, Herrero R. Prevention strategies for gastric cancer: a global perspective. Clin Endosc. 2014;47:478–89.

Kamran SC, Hong TS, Wo JY. Advances in the Management of Gastric and Gastroesophageal Cancers. Curr Oncol Rep. 2016;18:13.

Laks S, Meyers MO, Kim HJ. Surveillance for gastric cancer. Surg Clin North Am. 2017;97:317–31.

Park CH, Park JC, Chung H, Shin SK, Lee SK, Cheong JH, et al. Impact of the surveillance interval on the survival of patients who undergo curative surgery for gastric Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23:539–45.

Abe S, Oda I, Suzuki H, Nonaka S, Yoshinaga S, Nakajima T, et al. Long-term surveillance and treatment outcomes of metachronous gastric cancer occurring after curative endoscopic submucosal dissection. Endoscopy. 2015;47:1113–8.

Lee JH, Lim JK, Kim MG, Kwon SJ. The influence of post-operative surveillance on the prognosis after curative surgery for gastric cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 2014;61:2123–32.

Colquhoun A, Arnold M, Ferlay J, Goodman KJ, Forman D, Soerjomataram I. Global patterns of cardia and non-cardia gastric cancer incidence in 2012. Gut. 2015;64:1881–8.

Dai Q, Jiang L, Lin RJ, Wei KK, Gan LL, Deng CH, et al. Adjuvant chemoradiotherapy versus chemotherapy for gastric cancer: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Surg Oncol. 2015;111:277–84.

Oblak I, Vidmar MS, Anderluh F, Velenik V, Jeromen A. Capecitabine in postoperative radiochemotherapy for gastric adenocarcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:iv42.

Boda-Heggemann J, Hofheinz RD, Weiss C, Mennemeyer P, Mai SK, Hermes P, et al. Combined adjuvant radiochemotherapy with IMRT/XELOX improves outcome with low renal toxicity in gastric cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;75:1187–95.

Isa N. Evidence based radiation oncology with existing technology. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother. 2014;19:259–66.

Valentini V, Cellini F, Minsky BD, Mattiucci GC, Balducci M, D'Agostino G, et al. Survival after radiotherapy in gastric cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Radiother Oncol. 2009;92:176–83.

Zhou ML, Kang M, Li GC, Guo XM, Zhang Z. Postoperative chemoradiotherapy versus chemotherapy for R0 resected gastric cancer with D2 lymph node dissection: an up-to-date meta-analysis. World J Surg Oncol. 2016;14:209.

Li LL, Xie CY, Su HF. Benefit of radiotherapy on survival in resectable gastric carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Tumour Biol. 2014;35:4957–66.

Smalley SR, Benedetti JK, Haller DG, Hundahl SA, Estes NC, Ajani JA, et al. Updated analysis of SWOG-directed intergroup study 0116: a phase III trial of adjuvant radiochemotherapy versus observation after curative gastric cancer resection. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2327–33.

Cunningham D, Allum WH, Stenning SP, Thompson JN, Van de Velde CJ, Nicolson M, et al. Perioperative chemotherapy versus surgery alone for resectable gastroesophageal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:11–20.

Macdonald JS, Smalley SR, Benedetti J, Hundahl SA, Estes NC, Stemmermann GN, et al. Chemoradiotherapy after surgery compared with surgery alone for adenocarcinoma of the stomach or gastroesophageal junction. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:725–30.

Kassam Z, Lockwood G, O'Brien C, Brierley J, Swallow C, Oza A, et al. Conformal radiotherapy in the adjuvant treatment of gastric cancer: review of 82 cases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;65:713–9.

Hawrylewicz L, Leszczyński W, Namysł-Kaletka A, Bronclik I, Wydmański J. Protection of organs at risk during neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for gastric cancer based on a comparison between conformal and intensity-modulated radiation therapy. Oncol Lett. 2016;12:692–8.

Wang X, Shen Y, Zhu H, Zhao Y, Li Z, Qiu M, et al. A phase II trial of concurrent 3D-CRT/IMRT and oxaliplatin, 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin (FOLFOX) in gastric cancer patients with R0 gastrectomy and D2 lymph node dissection. Gastric Cancer. 2016;19:245–54.

Chopra S, Agarwal A, Engineer R, Dora T, Thomas B, Sonawone S, et al. Intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) is not superior to three-dimensional conformal radiation (3DCRT) for adjuvant gastric radiation: a matched pair analysis. J Cancer Res Ther. 2015;11:623–9.

Zhang T, Liang ZW, Han J, Bi JP, Yang ZY, Ma H. Double-arc volumetric modulated therapy improves dose distribution compared to static gantry IMRT and 3D conformal radiotherapy for adjuvant therapy of gastric cancer. Radiat Oncol. 2015;10:114.

Fang L. Short/mid-term efficacy and adverse reactions of three postoperative radiotherapy modalities for patients with gastric cancer. J Pract Oncol. 2015;30:367–70.

Liu GF, Bair RJ, Bair E, Liauw SL, Koshy M. Clinical outcomes for gastric cancer following adjuvant chemoradiation utilizing intensity modulated versus three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy. PLoS One. 2014;9:e82642.

Ling TC, Slater JM, Nookala P, Mifflin R, Grove R, Ly AM, et al. Analysis of intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT), proton and 3D conformal radiotherapy (3D-CRT) for reducing perioperative cardiopulmonary complications in esophageal cancer patients. Cancers. 2014;6:2356–68.

Dhanireddy B, Mourad WF, Patel S, Concert C, Ryniak M, Shourbaji RA, et al. The impact of different radiation therapy techniques on oncologic and functional outcomes of locally advanced laryngeal cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;90:S538.

Minn AY, Hsu A, La T, Kunz P, Fisher GA, Ford JM, et al. Comparison of intensity-modulated radiotherapy and 3-dimensional conformal radiotherapy as adjuvant therapy for gastric cancer. Cancer. 2010;116:3943–52.

Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283:2008–12.

Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25:603–5.

Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–34.

van Enst WA, Ochodo E, Scholten RJ, Hooft L, Leeflang MM. Investigation of publication bias in meta-analyses of diagnostic test accuracy: a meta-epidemiological study. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:70.

Boda-Heggemann J, Weiss C, Schneider V, Hofheinz RD, Haneder S, Michaely H, et al. Adjuvant IMRT/XELOX radiochemotherapy improves long-term overall- and disease-free survival in advanced gastric cancer. Strahlenther Onkol. 2013;189:417–23.

Goody RB, Mackay H, Pitcher B, Oza AM, Brlerley JD, Kim JHJ, et al. Prospective evaluation of quality of life (QOL) during a phase I/II study of adjuvant chemotherapy with image-guided high-precision radiotherapy for completely resected gastric cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34.

Deng QH, Li P, Yan FQ, Liu P, Lu K, Tang ZZ, et al. Comparison of desimetric parameters between IMRT and 3D-CRT for postoperative irradiation in locally advanced gastric carcinoma. Chinese J Cancer Prev Treat. 2011;18:713–5.

Murthy KK, Shukeili KA, Kumar SS, Davis CA, Chandran RR, Namrata S. Evaluation of dose coverage to target volume and normal tissue sparing in the adjuvant radiotherapy of gastric cancers: 3D-CRT compared with dynamic IMRT. Biomedical Imaging Interv J. 2010;6.

Ringash J, Perkins G, Brierley J, Lockwood G, Islam M, Catton P, et al. IMRT for adjuvant radiation in gastric cancer: a preferred plan? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;63:732–8.

Wei-gang HU, Zhen Z, Zhi-yong XU, Wei-lie GU, Hui-Zhong L, Shao-qin H. Comparison of dosimetry between three-dimension conformal and intensity modulated plan in postoperative radiotherapy for gastric cancer. Chinese J Radiat Oncol. 2007;16:273–6.

Wieland P, Dobler B, Mai S, Hermann B, Tiefenbacher U, Steil V, et al. IMRT for postoperative treatment of gastric cancer: covering large target volumes in the upper abdomen: a comparison of a step-and-shoot and an arc therapy approach. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;59:1236–44.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this manuscript and its Additional files.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FR and YZ conceived and coordinated the study; designed, performed, and analyzed the experiments; and wrote the manuscript. ZZ, HW, YC, and MW collected and analyzed the data. SL revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All analyses were based on previously published studies, and hence no ethical approval and patient consent were required.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Figure S1. Overall survival sensitivity. (TIF 383 kb)

Additional file 2:

Figure S2. Disease-free survival sensitivity. (TIF 353 kb)

Additional file 3:

Figure S3. Loco-regional recurrence sensitivity. (TIF 315 kb)

Additional file 4:

Figure S4. Toxicity sensitivity. (TIF 468 kb)

Additional file 5:

Data S1. Search strategy in PubMed. (DOCX 17 kb)

Additional file 6:

Table S1. Methodological quality of randomized controlled trials assessed using the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool. (DOC 30 kb)

Additional file 7:

Table S2. Methodological quality of cohorts assessed using the Newcastle–Ottawa scale. (DOCX 18 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Ren, F., Li, S., Zhang, Y. et al. Efficacy and safety of intensity-modulated radiation therapy versus three-dimensional conformal radiation treatment for patients with gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Radiat Oncol 14, 84 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13014-019-1294-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13014-019-1294-0