Abstract

Background

An epidemic of health disorders can be triggered by a collective manifestation of inappropriate behaviors, usually systematically fueled by non-medical factors at the individual and/or societal levels. This study aimed to (1) landscape and assess the evidence on interventions that reduce inappropriate demand of medical resources (medicines or procedures) by triggering behavioral change among healthcare consumers, (2) map out intervention components that have been tried and tested, and (3) identify the “active ingredients” of behavior change interventions that were proven to be effective in containing epidemics of inappropriate use of medical resources.

Methods

For this systematic review, we searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, the Cochrane Library, and PsychINFO from the databases’ inceptions to May 2019, without language restrictions, for behavioral intervention studies. Interventions had to be empirically evaluated with a control group that demonstrated whether the effects of the campaign extended beyond trends occurring in the absence of the intervention. Outcomes of interest were reductions in inappropriate or non-essential use of medicines and/or medical procedures for clinical conditions that do not require them. Two reviewers independently screened titles, abstracts, and full text for inclusion and extracted data on study characteristics (e.g., study design), intervention development, implementation strategies, and effect size. Data extraction sheets were based on the checklist from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews.

Results

Forty-three studies were included. The behavior change technique taxonomy v1 (BCTTv1), which contains 93 behavioral change techniques (BCTs), was used to characterize components of the interventions reported in the included studies. Of the 93 BCTs, 15 (16%) were identified within the descriptions of the selected studies targeting healthcare consumers. Interventions consisting of education messages, recommended behavior alternatives, and a supporting environment that incentivizes or encourages the adoption of a new behavior were more likely to be successful.

Conclusions

There is a continued tendency in research reporting that mainly stresses the effectiveness of interventions rather than the process of identifying and developing key components and the parameters within which they operate. Reporting “negative results” is likely as critical as reporting “active ingredients” and positive findings for implementation science. This review calls for a standardized approach to report intervention studies.

Trial registration

PROSPERO registration number CRD42019139537

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Epidemics, which traditionally refer to a widespread occurrence of an infectious disease in a community at a particular time, have in recent years been used to describe large-scale public health issues caused by a shared pattern of human behaviors that impact public health and well-being. An epidemic of health disorders can not only be triggered by organisms that cause communicable diseases, such as bacteria, viruses, fungi, or parasites, but also by a collective manifestation of inappropriate behaviors, usually systematically fueled by non-clinical factors at the individual and/or societal levels. When medicines or medical procedures are used for conditions for which they should not be used, they are deemed as inappropriate use of medical interventions. For example, the World Health Organization and governments have warned about the recent spike in the use of prescription drugs [1] and cesarean sections [2] globally, which has formed an epidemic that has caused avoidable damage to individual health and introduced excessive burdens on health systems [3, 4].

There have been experiments with programs specifically designed to address factors driving the epidemics of inappropriate use of medical interventions. These countermeasures are often non-clinical behavioral change interventions targeting physicians and pharmacists as a point-of-entry for interventions and are designed to improve clinical practices and policies that restrict unnecessary dispensing [5, 6]. These programs usually employed educational materials (e.g., guidelines, lectures, workshops) [7, 8], auditing and feedback on prescribing practices [9,10,11,12], or computer-aided clinical decision support systems [13]. A 2005 Cochrane review concluded that, for interventions occurring on multiple levels to be effective, local barriers to change—including the role patients play in driving inappropriate demand—must be addressed [14]. Current interventions to address the pressure of inappropriate demands outside the clinical setting range from national mass media campaigns to local interventions targeted at smaller communities [15], aiming to influence the knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards medical use of the general public who have yet to become healthcare consumers: namely patients and caretakers of patients [15,16,17]. However, recent reviews highlighted that critical knowledge gaps exist in the evidence for engaging healthcare consumers as active decision-makers for appropriate medical use (as opposed to passive receivers of education materials) [18, 19]. Furthermore, the lack of evidence in the development of and evaluation of the impact of these interventions, especially in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), complicates replication efforts [16, 17, 20].

The Behavioral Change Wheel (BCW) [21] and the behavior change techniques taxonomy volume 1 (BCTTv1) [22], developed by Michie and colleagues, facilitate researchers in organizing the content and components of behavioral interventions into nine intervention functions: education, persuasion, incentivization, coercion, training, enablement, modeling, environmental restructuring, and restrictions and assists them in translating specific techniques that were employed in a given intervention into change behaviors. Scientists have supported the use of BCW and BCTTv1 as a reliable and validated methodology that offers a common language for describing intervention components that can be used for the standardization of intervention content analysis and the development of interventions [23,24,25].

In this study, we aimed to (1) landscape and critically assess the evidence on non-clinical programs that reduce inappropriate or unnecessary use of medical interventions (i.e., medicines or medical procedures) by triggering behavioral change among healthcare consumers, (2) map out intervention components that have been tried and tested, and (3) identify the “active ingredients” of behavior change intervention programs that were proven to be effective in containing “epidemics of inappropriate use of medical interventions.”

Methods

Searches

For this systematic review, we searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, the Cochrane Library, and PsychINFO from the databases’ inceptions to May 2019, without language restrictions, for behavioral intervention studies. A search strategy was first developed for MEDLINE and adapted to other databases. The full-search strategy is detailed in Additional file 1. We searched for behavioral change interventions that aimed to reduce inappropriate or non-essential use of medical services or medicines that were driven by non-clinical factors and targeted health care consumers in the community, including primary care settings. For the purpose of this study, health care consumers included the public, patients, and caregivers (e.g., parents or guardians).

Study inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion and exclusion criteria used for all stages of the screening process are stated in Additional file 2. Studies had to be empirically tested by either randomized controlled trial (RCT), cluster-RCT (CRT), nonrandomized controlled trial (NCT), or interrupted times series (ITS) where the intervention time was clearly defined, and there were at least three data points both before and after the intervention, or quasi-experiments with a control group. To enable assessment of effectiveness in included interventions, this review excludes before/after evaluations of public campaigns or interventions that failed to employ a control group and therefore cannot show whether the effects of the campaign extended beyond trends occurring in the absence of the intervention. Outcomes of interest were reductions in inappropriate or non-essential use of medicines and/or medical procedures for clinical conditions that do not require them. Four major types of behaviors were identified, namely inappropriate antibiotic consumption (e.g., for viral infections or self-limiting conditions), elective cesarean section, demand for brand-name drugs that are available as generics, and non-medical use of prescription drugs, defined as “use without a prescription or use for reasons other than what the medication is intended for” [16, 26, 27]. Studies that focused only on change of knowledge or attitudes and did not report actual behavioral data were excluded. Studies mainly targeting clinicians, other healthcare staff, hospitals, inpatients, emergency care, or patients with mental health conditions were excluded. To create a distinction between interventions directed at health care consumers rather than providers, studies that aimed to modify clinical practices (e.g., prescribing) were excluded. Also, to differentiate behavior change interventions from therapies/treatments addressing mental health conditions such as addiction or depression, we excluded interventions for substance abuse, where inappropriate use was an outcome of a clinical condition, not a cause.

Data extraction strategy

All titles retrieved from the searches were imported into Endnote referencing software. Duplicates were removed. Titles and abstracts were independently screened for inclusion by two reviewers (L.L and P.A.) and removed if deemed irrelevant. Both authors independently screened the full text (n = 347) of the remaining studies to assess eligibility. Substantial agreement was found at all three stages (> 90%). Disagreements were resolved through discussion among reviewers to achieve consensus; any further discrepancies about study inclusion were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer (E.F. or J.H). We also manually searched the bibliographies of all the included studies and reference lists of relevant systematic reviews to identify additional citations.

We extracted the data on study characteristics: the country where the study was conducted, type of inappropriate use, target population, study design (e.g., RCT, controlled pre- and post-study [CPP]), data collection methods (e.g., survey, interview, medical records), and, when focused on a population study, sampling methodology (e.g., cluster, convenience), primary or main outcome measure, and conclusions reported. We further examined reporting on intervention development/adaption, design, and implementation strategies. Additionally, we extracted underlying theoretical domains, effect size, and risk of bias by two independent review authors, who determined the domains within the Behavioral Change Wheel (BCW) and identified the “active ingredients” of the interventions according to BCTTv1. Data extraction sheets were based on the checklist from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews [28]. The forms were modified after piloting on a sample of studies. When coding, we adopted the coding assumptions reported by Presseau et al. [25] that BCTs worked through targeting the behavior of health care consumers, or both the behavior of health care consumers and providers. We also assumed policy interventions and national campaigns were driven by governments and therefore coded governments as implementers for respective interventions. After the data extraction phase, we identified critical evidence gaps in evaluation data and processes of intervention development and implementation. We therefore conducted another round of targeted, investigative searches, involving citation and publication searches on first, last, and corresponding authors of selected interventions, seeking formative, process, and impact evaluation data.

Study quality assessment

We conducted and reported the review in line with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement (PRISMA). Risk of bias was assessed by two reviewers using the Effective Public Health Practice Project’s (EPHPP) Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies [29], which includes eight components (21 items): selection bias, study design, confounders, blinding, data collection methods, withdrawals or dropouts, intervention, and integrity. A rating of weak, moderate, or strong was given to each of the first six components, and these scores contributed to a global rating for the study. Qualitative data was assessed by the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist.

Data synthesis on active ingredients

Using BCW domains and BCT taxonomies, we analyzed descriptions of all interventions and identified the commonly targeted aspects by looking at the frequency with which BCW domain and BCT of the interventions were incorporated in the studies. We also explored the nature and pattern of the use of these active ingredients across the different studies, and the associated magnitude of effect size. We descriptively reported the active ingredients and primary outcomes’ effect sizes at the study level, counting the number of times a BCW domain and a BCT had been identified across studies and in different types of use behaviors and presented a description of features of included interventions.

Results

Review statistics

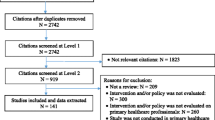

Our systematic search of the literature yielded 4045 results through database searching and an additional 238 were identified through bibliography searches. After de-duplication and title and abstract screening, 347 references were assessed in full text. A flow diagram of the study selection process is shown in Fig. 1. Forty-three studies (representing 43 interventions, see Additional file 3)—conducted between 1994 and May 2019 and meeting inclusion criteria—were included in the systematic review. Twenty-five studied interventions focused on the reduction of antibiotic use—eight on elective cesarean section, four on the conversion from brand name drugs to generic equivalents, and six on nonmedical use of prescription drugs. Table 1 provides an overview of the included intervention studies for full-text extraction including intervention aims and components.

Study characteristics

All included studies were published in English. Twenty-four in North America (excluding Mexico; USA: n = 21, Canada: n = 3), four in Latin America (Chile, Colombia, Venezuela, Brazil, and Mexico), four in the Middle East (Iran), eight in Europe (France, UK, Italy, Spain, and Moldova), three in East Asia and Pacific (Australia and Singapore), and none from sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, or the Caribbean. The imbalance between high-income countries (HICs) and low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) is apparent when characterizing types of inappropriate use. Multifaceted interventions are scarce and limited to HICs while interventions in LMICs were limited to primary care settings or policy restrictions (on over-the-counter purchases) with zero community-based programs identified. No studies from LMICs focused on demands for brand-name drugs or non-medical use of prescription drugs.

Study design

The included studies consisted of 18 RCTs and five NCTs, eight ITS, and 12 quasi-experimental studies. These studies varied in their quality, methodological design, and implementation. Twenty-four studies reported longitudinal data; the rest employed cross-sectional study designs. All were outcome evaluation studies. In terms of data collection methods for evaluation, 23 studies employed surveys and 30 utilized medical record data—these were not mutually exclusive. Four studies reported cost data. One study employed interviews as part of the intervention procedure, but not for evaluation purposes [51]. No qualitative data were reported in the initial included studies; we therefore conducted a targeted, investigative search on the selected interventions, but only located minimal formative data on some of the studies [30, 45,46,47, 50]. One UK-based project that aimed to improve the decision-making around mode of delivery among pregnant women published comprehensive implementation research data from pilot results [48] and study protocol [47] to outcome and economic evaluation [45, 46, 49, 52, 53]. Table 2 presents a summary of the key characteristics of each study measuring behavioral outcomes and reported formative and relevant evaluation data of the included interventions.

Study quality assessment

Study quality varied by domain assessed based on the primary behavioral outcomes (Additional file 4). There were 11 studies of overall strong quality, 12 of overall moderate quality, and 20 of overall low quality. In order to provide an overview of the entire literature, no studies were excluded based on their methodological quality. The majority of behavior outcomes were derived from medical records, leaving minimal room for reporting errors with the exception that some only relied on self-reported data for evaluation.

Active ingredients of the behavior change interventions

All of the interventions utilized multiple behavior change techniques (BCTs) with a primary aim to improve health care consumers’ behavior. Table 3 presents the features of all the included interventions; the frequency distributions of BCTs employed are presented in Fig. 2. Of all 93 BCTs in the taxonomy, 19 (19/93, 22.9%) were used as active ingredients in the included interventions: four BCTs were used exclusively for interventions targeting health care consumers (BCTs 3.3, 6.1, 9.2, 12.2); another four were used exclusively for multifaceted interventions that also targeted providers (BCTs 1.3, 2.2, 3.2, 14.2), with 11 BCTs used for both (BCTs 3.1, 4.1, 4.2, 5.1, 5.2, 8.2, 9.1, 10.1, 10.2, 12.1, 12.5; see Tables 4 and 5 for details). When compared with the principles in the Behavioral Change Wheel, 39 interventions employed education as an active ingredient followed by enablement (n = 12), environmental restructuring (n = 8), and restriction (n = 4). Of the 43 included studies, 22 were interventions delivered only at the community level, 12 in primary care settings, six in both community and primary care settings, and three in schools. Nineteen interventions were delivered on an individual basis, which tended to be shorter in duration, ranging from one to multiple short sessions. The majority of studies focused on evaluation design and outcomes and only provided high-level descriptions of the intervention, with or without details on the development or implementation processes. Twenty studies provided clear descriptions on the intervention adaption/development process, all on implementation strategies (e.g., channels and timing of dissemination), and, to a certain level, 15 on intervention dose (intensity) [54,55,56] and nine on designs (e.g., color and format) [55,56,57,58]. Some studies provided links to intervention designs, but most of these links had expired. Only eight interventions explicitly reported having adopted a theory or model of behavioral change, which included social marketing [56, 59, 60], social cognitive theory [55], precede/proceed model [61], social development model [39, 40], and the health belief model [62]. However, little was reported on how these underlying theories were used in the development and evaluation of the interventions.

Interventions targeting health care consumers

Table 4 reports the individual BCTs identified within the descriptions as active ingredients of the selected interventions targeting health care consumers. Of the 93 BCTs, the most frequently used active ingredients in the selected interventions targeting health care consumers were BCTs: 4.1-Instruction on how to perform the behavior (n = 34), 4.2 Information about antecedents (n = 22), 5.1 Information about health consequences (n = 22), followed by 12.5 Adding objects to the environment (n = 12), 8.2 Behavior substitution (n=11), and 12.1 Restructuring the physical environment (n = 8). Most studies employed education interventions aiming to improve public knowledge (including awareness or correcting misconceptions). Mass media campaigns were widely used to reduce antibiotic misuse [54,55,56, 60, 63,64,65,66,67,68] and demand for brand-name drugs [69], all in HIC. The effectiveness of such behavioral change interventions was mixed. Decision aids to assist pregnant women making decisions about mode of delivery were tested in three different trials in Australia, UK, and USA; all reported to be ineffective [52, 70, 71]. Taylor et al. [72], Lee et al. [73], and Vallès et al. [51] trialed patient-based education interventions in primary care settings to reduce antibiotic use or to substitute generic for brand-name drugs; only Vallès et al.’s [51] intervention found a positive impact on behavior change. Mainous et al. and McNulty et al. assessed community-wide education interventions in the USA and UK on their effectiveness in improving public antibiotic use and found the provision of educational messages itself was insufficient to overcome the influence of past attitudes and behaviors [57, 66]. Formal and informal social support networks can be leveraged to influence individuals’ behaviors through improving doctor-patient communication [58,59,60, 64, 72, 74] or by actively engaging family members in the process [39, 40, 75]. Four interventions aimed to encourage disposal of leftover opioids among postoperative patients by employing a combination BCWs of education, enablement, and environment restructuring (BCTs: 4.1, 4.2, 5.1, 5.2, 8.2, 12.1, 12.5), which reported positive impact [76,77,78,79]. Two longitudinal RCTs on school-based universal preventive interventions in the USA that aimed to strengthen families and build life skills were introduced to middle schoolers [39, 40] and reported a lasting impact on preventing non-medical use of prescription drugs into adulthood. Structural environmental conditions regarding access to healthcare services and medicines, and promotive and restrictive policies—or the lack thereof—can be pathways to shaping individual behaviors. Two trend analyses assessing the effectiveness of French public education campaigns [63, 68] reported a significant reduction in antibiotic consumption rates; however, trials on community-wide public campaigns with academic detailing for practitioners did not demonstrate comparable levels of improvement in public antibiotic use. Belongia et al. and Fiskelstein et al. found little or no evidence—attributable to multi-year interventions in Wisconsin and Massachusetts—on reductions in antibiotic prescribing in the intervention areas, despite improved public knowledge [54, 59, 74]. Gonzales et al. found that the state-wide “Get Smart Colorado” campaign did not improve prescription rates, but might be associated with a reduction in antibiotic use in the community through decreases in office visit rates among children [56, 64]. Four studies evaluated the effectiveness of the restrictions on OCT purchases on antibiotic consumption in five Latin American countries with mixed results [33,34,35, 80].

Interventions also targeting health care providers

Table 5 reports the individual BCTs identified within the descriptions as active ingredients of the selected interventions targeting health care providers. The most frequently used BCTs targeting health care providers were similar with those targeting consumers, with small differences in the ranking: BCTs: 4.1 Instruction on how to perform the behavior (n = 15), 4.2 Information about antecedents (n = 13), 12.5 Adding objects to the environment (n = 10), followed by 5.1 Information about health consequences (n = 9), 8.2 Behavior substitution (n = 9), and 12.1 Restructuring the physical environment (n = 4). We noticed that, except for programs aiming to contain inappropriate use of antibiotics, other interventions had limited engagement between consumers and providers.

Discussion

Summary of findings

Using the Behavioral Change Wheel (BCW) domains to identify the theoretical concepts underlying interventions and the behavior change technique taxonomy v1 (BCTTv1) to identify the active ingredients of interventions, we found that the domain of education was the most commonly targeted by a majority of interventions with primary focus on the provision of information on BCTs 4.1 how to perform the behavior and 4.2 about antecedents and 5.1 the associated health consequences. A plethora of evidence supports the view that human behaviors should be understood in their social ecological context, as products of intertwined influences at the personal, communal, societal, and structural levels [81,82,83]. Studies show that improving knowledge and awareness does not equate with appropriate behavior change, as lack of information is often not the only barrier to changing behavior [64, 66, 84,85,86]. The effects of education interventions have been mixed—most likely due to heterogeneity in context, population served, and intervention design and measures. Cabral et al. examined how communication affects prescription decisions for acute illnesses and demonstrated a clear miscommunication with cross-purposes between health care consumers and providers, as patients and/or caregivers focused on their concerns and information needs, which clinicians interpreted as an expectation for antibiotics [87]. This review supports the use of multifaceted (complex) interventions that incorporate BCTs related to provision of information (BCTs 4.1, 4.2, or 5.1) and, as an alternative to antibiotics, prescription pads with clear explanations on symptoms, and appropriate treatment options (BCT 8.2), as education alone is not sufficient to be effective. Interventions consisting of health education messages (e.g., BCTs 4.1, 4.2, 5.1), recommended behavior alternatives (BCT 8.2), and a supporting environment that incentivizes or encourages the adoption of a new behavior (e.g., BCTs 10.1, 10.2, 12.1, 12.5) are more likely to be successful. Other types of utilized behavior change techniques often aimed to encourage alternative behaviors and improve the physical environments via regulations or mass media.

The continuing tendency in research reporting has been to stress the effectiveness of interventions rather than the process of identifying and developing key components and the parameters within which they operate. There is a lack of detail on how the intervention components were selected, designed, and the process of implementing them, with limited descriptions provided on the “contexts” and “mechanisms” that determine the effectiveness of interventions. Few studies provided sufficient details on intervention development, dose/intensity, and design; some provided links to project materials that had expired [54,55,56, 60]. The majority of the selected interventions did not describe the pilot or process data for implementation, nor did they discuss the dissemination of findings and pathways to impact. Even after identifying active ingredients of interventions using BCTTv1, without a complete “recipe,” one cannot recreate successes in other contexts. Just like there are agreed-upon elements that constitute a rigorous and comprehensive reporting of evaluation studies, publications on behavioral change interventions should systematically cover a standardized list of intervention elements from the development, adaption and refinement, feasibility and pilot-testing, implementation, evaluation, and reporting of BCTs. The CONSORT-SPI team [88] has developed guidance and checklists for the reporting of BCT trials; however, the required details on the reporting are still primarily focused on evaluation study designs (e.g., process of randomization) rather than BCT development and implementation. From implementation research perspective and following the Medical Research Council (MRC) guidance on developing and evaluating complex interventions, reporting of BCT development and implementation should include descriptions on the context, target behavior determinants, theories and rationale (theory of change), intervention design features, adaption/development process, implementation strategy (e.g., implementor, dose/intensity), modifications made between the feasibility and effective assessment phases, and evaluation outcomes. The lack of detailed reporting among included intervention studies on evidence-based development and implementation processes undermines the generalizability of study findings, makes cross-intervention comparisons difficult, and complicates future adaption and replication efforts.

This systematic literature review is the first on the effectiveness of public-targeted behavioral change interventions to reduce inappropriate use of medical interventions. It identified a serious lack of formative data, which means that interventions to change public use of medical interventions are often designed on the basis of “best guesses” of what needs to change, without an evidence base or explicit rationale for the selection of a specific intervention strategy. There is an urgent need to adopt a multidisciplinary, systematic approach to developing evidence-based behavioral change interventions to reduce inappropriate medical use and to develop an operational mechanism for knowledge translation and scale-up within and across different countries. We found limited evidence [39, 63] on evaluating the impact of previous or ongoing education interventions on inappropriate use in terms of long-term impact, scalability, and replicability. The root causes of why certain interventions were unsuccessful are not systematically explored or reported, yet reporting “negative results” is likely as critical as reporting “active ingredients” and positive findings for the development and sustainability of implementation science.

Relation to other studies

Like most stewardship programs, quaternary prevention—a relatively new category of medical prevention first raised in 1986 by Dr. Marc Jamoulle, a family physician, to addressing concerns around the protection of people and patients from being harmed by over-diagnosis or overtreatment—tends to focus mostly on health care providers while placing less attention on consumers [5, 89,90,91]. The definition of quaternary prevention was later expanded by Brodersen et al. in 2014 to include patients and medical interventions as an action taken to protect individuals (persons/patients) from medical interventions that are likely to cause more harm than good [92, 93]. The expanded definition recognizes the contemporary reality in medicine in which people may suffer harm from medical interventions throughout their entire lifetime—from conception to adulthood, in times of good health, as well as when experiencing self-limited disease, chronic conditions, or terminal disease. Therefore, quaternary prevention should include preventing all types of harm associated with medical interventions [92, 93]. From this perspective, quaternary prevention is aligned with the aims of the behavioral change interventions and techniques identified in our review and should be considered alongside the other four classical levels of preventive activities, i.e., primordial (e.g., laws that restrict over-the-counter purchases of antibiotics), primary (e.g., prescription drugs disposal programs), and secondary and tertiary preventions (e.g., interventions that reduce fear of childbirth or convert demand of brand-name drugs to generic drugs).

The use of medicine or medical procedures is a highly complex set of behaviors involving multiple actions, including the self-diagnostic process, assessing benefit/risk, decision-making around healthcare seeking and treatment choice, and review of treatment—each performed at different time points across the care continuum [94, 95]. It involves interactions with various stakeholders (i.e., family members and providers) and is often shaped more by individual and contextual factors than by a clinical diagnosis [94, 95]. Therefore, developers and implementers of behavioral change interventions should be clear as to whose and which behaviors are being targeted for change and how—namely, who needs to do what differently, how, to whom, where, when, and for how long. A set of precisely specified behaviors would allow for easier measurement and therefore would offer a baseline and metric for evaluating the success of an intervention.

In order to develop effective behavioral change interventions, we first need to explain why people behave in certain ways, yet a more in-depth look at people’s lifeworld is lacking from every reviewed article. As the dual processing theory (DPT) posits, human behavior is guided by two types of processing mechanisms: the implicit, intuitive system 1 and the explicit, rational system 2 [96]. Behavioral economists elaborate that, due to limited self-control, rationality and social preferences, actual decisions are less rational and stable than traditional normative theory suggests [96]. They are usually made with a range of biases resulting from the way people think and feel, rather than with rationality or full information. However, most of the included interventions—appealing to system 2 processing—attempted to influence behaviors via improved knowledge and attitudes; disappointingly, many trials indicated that this did not automatically lead to preferred behaviors [54, 59, 72, 74]. To complicate things further, Zinn argues that between rationality and irrationality, there is a third, “in-between” dimension that includes trust, intuition, and emotion, which is an important aspect of decision-making when people deal with risk and uncertainty, especially in anticipation of the possible undesired outcomes of decisions [97]. This may explain why three RCTs on decision aids (system 1) to address individual emotions (system 2) had no real impact on choice of vaginal birth [52, 70]. On the other hand, in addition to education programs, financial incentives (changes in co-payment), free medicine, advertisements (print media), and health policies have been experimented with as behavioral change interventions to influence healthcare consumers’ choice of medicine—in particular, to promote uptake of generic medicines—though they have demonstrated inconsistent results [98, 99].

The most promising measure was an intervention delivered face-to-face, where consumers were told that they had the option of switching back to brand-name drugs anytime [51, 100, 101]; hence, an intervention that leverages human behavioral mechanisms may be more effective and cost-effective in optimizing decision making than repeated, expensive education campaigns. In response to the recent opioid epidemic across the globe, promising prevention programs aimed not only to improve the knowledge and awareness of the risk of nonmedical use of prescription drugs among at risk individuals, but also to empower healthcare consumers by providing skills or tools that enable them to take action prior to the occurrence of misuse and/or before the development of poor habits [39, 40, 76,77,78,79]. These interventions further improved the socio-ecological surroundings of the target audience by involving family members and restructuring their social or physical environments [39, 40, 76,77,78,79].

Our review showed only 19% of BCTs have been utilized by included interventions (i.e., 81% of BCTs unexplored), with great variation between different types of misuse—most were limited to education. Future studies should explore other BCTs. A wide range of disciplines engaging in social and behavioral sciences, such as psychology, sociology, anthropology, communication, and marketing, can provide theories, models, and methods for a more comprehensive and coherent approach to understanding or even modifying contextual, organizational and interpersonal determinants of behavior. In terms of sustainability of the interventions themselves, other than a few longitudinal studies [39, 40], we do not know how long the reported effect of behavioral change will sustain. Few studies incorporated economic evaluations, and therefore, it was not possible to determine the returns on investment (ROI) for these included interventions. Future intervention studies should consider the aspects of RE-AIM (Reach Effectiveness Adoption Implementation Maintenance) framework or follow the MRC Guidelines on Developing and Evaluating Complex Interventions during the planning stage to enhance the impact of interventions and the reporting of them.

Development of a behavioral change intervention has to start with a realist, comprehensive understanding of the complex environment that shapes individual and collective behaviors. The etiology of inappropriate use of medical interventions should be studied and addressed within the context of its biological, psychosocial, behavioral, and environmental factors and the interactions between them. In early 2000, Sallies et al. developed a behavioral epidemiology framework, which specified a systematic sequence of studies on health-related behaviors leading to evidence-based interventions directed at populations in the following five phases: (1) establish links between behaviors and health, (2) develop measures of the behavior, (3) identify influences on the behavior, (4) evaluate interventions to change the behavior, and (5) translate research into practice [21, 83, 102]. In 2011, Michie and colleagues mapped out various pathways to influencing behavioral change and recommended that interventions seeking to change behavior should be designed on the basis of a thorough “behavioral diagnosis” of why behaviors are the way they are and what needs to change in order to bring about the desired behavior [21]. Conducting such diagnosis should be facilitated by the use of behavioral theory. Not until recent years did researchers systematically report efforts in the identification of the root causes of operational barriers and facilitators in designing, implementing, and evaluating interventions. For instance, in 2018 and 2019, Langdridge et al. have attempted to decipher the intervention elements and visual imagery used in public antimicrobial stewardship [23, 103].

Consistent with the findings from recent reviews by Cochrane and the Department of Health and Social Care and Public Health in England [5, 104, 105], our review found that few interventions employed behavior change theories or techniques. Behavioral determinants and social influences are often not given sufficient consideration in the design and evaluations of interventions. To inform the design of effective, context-specific behavior change interventions, one must first define the problem in both behavioral terms and in its current context and adopt a theory-driven, systematic approach to intervention design. This points to another critical knowledge gap identified by this review in implementation science, namely early studies that take place prior to the implementation of behavioral change interventions. Following the Medical Research Council (MRC) guidelines on developing and evaluating complex interventions [106], as presented in Table 1, we find there is little reporting on the feasibility, pilot, or process data that generates the needed contextual information and evidence base for acceptance, adaption, and uptake. Limited detail has been made available on the development of the included interventions regarding how key decisions were made, including feasibility and compliance. Future research on pilot and/or feasibility studies that aim to strengthen large-scale behavioral change intervention design can span the continuum of implementation science research from idea generation to intervention development, implementation, evaluation, and scale-up.

Limitations

This systematic review is subject to important limitations as we worked with interventions that are complex, heterogeneous, non-standardised, and targeted different types of inappropriate use of medical interventions and users. The diversity in the design and outcome measures of the included interventions prevents us from performing a meta-analysis. We demonstrated great variability in the effect size observed within each behavioral change intervention considered. We cannot make a conclusion that certain types of behavioral change intervention might be more effective than any other type of design due to the limitations of the literature relating to the lack of evidence-based development process and evaluation design. Behavioral data that were gathered via survey instruments were by nature self-reported from health care consumers who may have been reluctant to report practices that could be considered inappropriate or may have been subject to recall bias. Often there were more than one “active ingredient” identified for each included intervention, yet retrospective coding and the study design did not allow us to pinpoint which component was more effective. Further, some studies contained bundles of interventions while others contained similar, yet different interventions implemented in multiple countries; therefore, the results of this review may have been clouded by unconsidered/unreported intervention components in the studies included. The studies in this review were spread across a wide range of settings and populations, so general conclusions should be drawn with caution. Publication bias may be a critical problem since it implies that most interventions have a positive effect. We expect most interventions aimed at individuals to be much more complex in reality; however, this review was not able to capture how and why “active ingredients” were selected, implemented, or functioned in the respective socioeconomical, cultural, and healthcare settings. Future work should focus on addressing the limitations and uncertainties surrounding existing behavioral change interventions.

Conclusion

Systematically assessing the evidence across behavioral change interventions allows for the identification of the “active ingredients” of effective interventions that improve healthcare consumers’ use of medical interventions, as well as the identification of those with ineffective or uncertain outcomes. Although opportunities for behavioral change interventions are becoming more commonly recognized, multifaceted (complex) interventions are still new, scarce, limited to high-income countries, and, as is evident from our findings, highly heterogeneous. Public-targeted behavioral change interventions in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) were exclusively limited to primary care settings. Interventions that consist of health education messages, recommended behavior alternatives, and a supporting environment that incentivizes or encourages the adoption of a new behavior are more likely to be successful. Future research should also seek to unpack the distinctions between various audience segments, the influence of the social ecological context, and the utility of the unexplored 81% of behavioral change techniques (BCTs). It is critical to adhere to a rigorous framework that guides the development, implementation, evaluation, and reporting of evidence-based interventions, so that generated evidence can be documented, disseminated, compared, and utilized for further research. The lack of reporting on evidence-based development and implementation processes makes cross-intervention comparisons and replication difficult. Our review further identified a need for standardized reporting of intervention development, adaptation, and implementation to maximize generalisability and replicability.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ABR:

-

Antibiotic resistance

- AMR:

-

Antimicrobial resistance

- BCT:

-

Behavior change technique

- BCTT:

-

Behavior change technique taxonomy

- BCW:

-

Behavioral Change Wheel

- CPP:

-

Controlled pre- and post-study

- CRT:

-

Cluster randomized control trial

- CS:

-

Elective cesarean section

- DPT:

-

Dual processing theory

- EPHPP:

-

Effective Public Health Practice Project’s Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies

- HIC:

-

High-income country

- ITS:

-

Interrupted time series

- LMIC:

-

Low- and middle-income country

- MoD:

-

Mode of delivery

- MRC:

-

Medical research council

- NA:

-

Not applicable

- NR:

-

Not reported

- NCT:

-

Nonrandomized controlled trial

- OTC:

-

Over-the-counter purchases

- PDM:

-

Prescription drug misuse

- PRISMA :

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- RCT:

-

Randomized control trial

- ROI:

-

Returns on investment

- VD:

-

Normal vaginal delivery

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Scholl L, Seth P, Kariisa M, Wilson N, Baldwin G., Drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths – United States, 2013-2017. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. ePub: 21 December 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/67/wr/mm675152e1.htm?s_cid=mm675152e1_w (Last accessed: July 2019). 2018.

The Lancet. Stemming the global caesarean section epidemic. Lancet. 2018;392(10155):1279.

Boerma T, et al. Global epidemiology of use of and disparities in caesarean sections. Lancet. 2018;392(10155):1341–8.

Jones MR, et al. A brief history of the opioid epidemic and strategies for pain medicine. Pain and therapy. 2018;7(1):13–21.

Pinder, R., et al., Behaviour change and antibiotic prescribing in healthcare: a literature review and behavioural analysis. (https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/405031/Behaviour_Change_for_Antibiotic_Prescribing_-_FINAL.pdf (Last accessed in November 2018). 2015, Public Health England London.

Johnson MJ, May CR. Promoting professional behaviour change in healthcare: what interventions work, and why? A theory-led overview of systematic reviews. BMJ Open. 2015;5(9):e008592.

Chhina HK, et al. Effectiveness of academic detailing to optimize medication prescribing behaviour of family physicians. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2013;16(4):511–29.

Forsetlund L, et al. Continuing education meetings and workshops: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;2009(2):Cd003030.

Tuti T, et al. A systematic review of electronic audit and feedback: intervention effectiveness and use of behaviour change theory. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):61.

Arditi C, et al. Computer-generated reminders delivered on paper to healthcare professionals: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;7:Cd001175.

Cheung A, et al. Overview of systematic reviews of the effectiveness of reminders in improving healthcare professional behavior. Syst Rev. 2012;1:36.

Ivers N, et al. Audit and feedback: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(6):Cd000259.

Van de Velde S, et al. A systematic review of trials evaluating success factors of interventions with computerised clinical decision support. Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):114.

Arnold SR, Straus SE. Interventions to improve antibiotic prescribing practices in ambulatory care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(4):Cd003539.

Cross EL, Tolfree R, Kipping R. Systematic review of public-targeted communication interventions to improve antibiotic use. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2017;72(4):975–87.

Huttner B, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of public campaigns aimed at improving the use of antibiotics in outpatients in high-income countries. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10(1):17–31.

Huttner B, Harbarth S, Nathwani D. Success stories of implementation of antimicrobial stewardship: a narrative review. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20(10):954–62.

Ryan R, et al. Consumer-oriented interventions for evidence-based prescribing and medicines use: an overview of systematic reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(5):Cd007768.

Ryan R, et al. Interventions to improve safe and effective medicines use by consumers: an overview of systematic reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(4):Cd007768.

de Kraker MEA, et al. Good epidemiological practice: a narrative review of appropriate scientific methods to evaluate the impact of antimicrobial stewardship interventions. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2017;23(11):819–25.

Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implementation Science. 2011;6(1):42.

Michie S, et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2013;46(1):81–95.

McParland JL, et al. What are the 'active ingredients' of interventions targeting the public's engagement with antimicrobial resistance and how might they work? Br J Health Psychol. 2018;23(4):804–19.

Kebede MM, et al. Characterizing active ingredients of eHealth interventions targeting persons with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes mellitus using the behavior change techniques taxonomy: scoping review. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(10):e348.

Presseau J, et al. Using a behaviour change techniques taxonomy to identify active ingredients within trials of implementation interventions for diabetes care. Implement Sci. 2015;10:55.

Roque F, et al. Educational interventions to improve prescription and dispensing of antibiotics: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:1276.

Martins SS, Ghandour LA. Nonmedical use of prescription drugs in adolescents and young adults: not just a Western phenomenon. World psychiatry: official journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA). 2017;16(1):102–4.

Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from http://handbook.cochrane.org. 2011.

Armstrong R, Waters E. and D. J., Chapter 21: reviews in health promotion and public health. In: J Higgins, S Green, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.10. London: The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011.

Stille CJ, et al. Physician responses to a community-level trial promoting judicious antibiotic use. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6(3):206–12.

Gonzales R, et al. Decreasing antibiotic use in ambulatory practice: impact of a multidimensional intervention on the treatment of uncomplicated acute bronchitis in adults. Jama. 1999;281(16):1512–9.

McNulty CA, et al. Expectations for consultations and antibiotics for respiratory tract infection in primary care: the RTI clinical iceberg. Br J Gen Pract. 2013;63(612):e429–36.

Santa-Ana-Tellez Y, et al. Impact of over-the-counter restrictions on antibiotic consumption in Brazil and Mexico. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e75550.

Santa-Ana-Tellez Y, et al. Seasonal variation in penicillin use in Mexico and Brazil: analysis of the impact of over-the-counter restrictions. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59(1):105–10.

Wirtz VJ, et al. Analysing policy interventions to prohibit over-the-counter antibiotic sales in four Latin American countries. Trop Med Int Health. 2013;18(6):665–73.

Dreser A, et al. Regulation of antibiotic sales in Mexico: an analysis of printed media coverage and stakeholder participation. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:1051.

Gandhi T, Best K. Educate patients about proper disposal of unused Rx medications-for their safety. Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(4):8.

Verde Technologies. Deterra Drug Deactivation System - Deterra System (https://deterrasystem.com/ Last accessed June 2019).

Spoth R, et al. Longitudinal effects of universal preventive intervention on prescription drug misuse: three randomized controlled trials with late adolescents and young adults. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(4):665–72.

Spoth R, et al. Long-term effects of universal preventive interventions on prescription drug misuse. Addiction. 2008;103(7):1160–8.

Spoth R, et al. Replicating and extending a model of effects of universal preventive intervention during early adolescence on young adult substance misuse. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2016;84(10):913–21.

Spoth R, et al. Universal intervention effects on substance use among young adults mediated by delayed adolescent substance initiation. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77(4):620–32.

Spoth R, et al. Replication RCT of early universal prevention effects on young adult substance misuse. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2014;82(6):949–63.

Spoth RL, et al. Longitudinal substance initiation outcomes for a universal preventive intervention combining family and school programs. Psychol Addict Behav. 2002;16(2):129–34.

Frost J, et al. Women's views on the use of decision aids for decision making about the method of delivery following a previous caesarean section: qualitative interview study. Bjog. 2009;116(7):896–905.

Emmett CL, et al. Women's experience of decision making about mode of delivery after a previous caesarean section: the role of health professionals and information about health risks. Bjog. 2006;113(12):1438–45.

Montgomery AA. The DiAMOND trial protocol: a randomised controlled trial of two decision aids for mode of delivery among women with a previous caesarean section [ISRCTN84367722]. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2004;4(1):25.

Emmett CL, et al. Decision-making about mode of delivery after previous caesarean section: development and piloting of two computer-based decision aids. Health Expect. 2007;10(2):161–72.

Hollinghurst S, et al. Economic evaluation of the DiAMOND randomized trial: cost and outcomes of 2 decision aids for mode of delivery among women with a previous cesarean section. Med Decis Making. 2010;30(4):453–63.

Shorten A, et al. Making choices for childbirth: development and testing of a decision-aid for women who have experienced previous caesarean. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;52(3):307–13.

Valles JA, et al. A prospective multicenter study of the effect of patient education on acceptability of generic prescribing in general practice. Health Policy. 2003;65(3):269–75.

Montgomery AA, et al. Two decision aids for mode of delivery among women with previous caesarean section: randomised controlled trial. Bmj. 2007;334(7607):1305.

Emmett CL, Montgomery AA, Murphy DJ. Preferences for mode of delivery after previous caesarean section: what do women want, what do they get and how do they value outcomes? Health Expect. 2011;14(4):397–404.

Belongia EA, et al. Impact of statewide program to promote appropriate antimicrobial drug use. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11(6):912–20.

Cebotarenco N, Bush PJ. Reducing antibiotics for colds and flu: a student-taught program. Health Educ Res. 2008;23(1):146–57.

Gonzales R, et al. "Get smart Colorado": impact of a mass media campaign to improve community antibiotic use. Med Care. 2008;46(6):597–605.

McNulty CA, et al. The English antibiotic awareness campaigns: did they change the public's knowledge of and attitudes to antibiotic use? J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65(7):1526–33.

Wutzke SE, et al. Evaluation of a national programme to reduce inappropriate use of antibiotics for upper respiratory tract infections: effects on consumer awareness, beliefs, attitudes and behaviour in Australia. Health Promot Int. 2007;22(1):53–64.

Finkelstein JA, et al. Impact of a 16-community trial to promote judicious antibiotic use in Massachusetts. Pediatrics. 2008;121(1):e15–23.

Formoso G, et al. Feasibility and effectiveness of a low cost campaign on antibiotic prescribing in Italy: community level, controlled, non-randomised trial. Bmj. 2013;347:f5391.

Fraser W, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a prenatal vaginal birth after cesarean section education and support program. Childbirth Alternatives Post-Cesarean Study Group. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176(2):419–25.

Hassani L, et al. The effect of an instructional program based on health belief model in decreasing cesarean rate among primiparous pregnant mothers. J Educ Health Promot. 2016;5:1.

Bernier A, et al. Outpatient antibiotic use in France between 2000 and 2010: after the nationwide campaign, it is time to focus on the elderly. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58(1):71–7.

Gonzales R, et al. The "minimizing antibiotic resistance in Colorado" project: impact of patient education in improving antibiotic use in private office practices. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(1):101–16.

Lambert MF, Masters GA, Brent SL. Can mass media campaigns change antimicrobial prescribing? A regional evaluation study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;59(3):537–43.

Mainous AG 3rd. V.A. Diaz, and M. Carnemolla, A community intervention to decrease antibiotics used for self-medication among Latino adults. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(6):520–6.

Perz JF, et al. Changes in antibiotic prescribing for children after a community-wide campaign. Jama. 2002;287(23):3103–9.

Sabuncu E, et al. Significant reduction of antibiotic use in the community after a nationwide campaign in France, 2002-2007. PLoS Med. 2009;6(6):e1000084.

O'Malley AJ, et al. Impact of alternative interventions on changes in generic dispensing rates. Health Serv Res. 2006;41(5):1876–94.

Shorten A, et al. Making choices for childbirth: a randomized controlled trial of a decision-aid for informed birth after cesarean. Birth. 2005;32(4):252–61.

Eden KB, et al. A randomized comparative trial of two decision tools for pregnant women with prior cesareans. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2014;43(5):568–79.

Taylor JA, Kwan-Gett TS, McMahon EM Jr. Effectiveness of a parental educational intervention in reducing antibiotic use in children: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;24(6):489–93.

Lee, M.H.M., et al., Results from a patient-based health education intervention in reducing antibiotic use for acute upper respiratory tract infections in the private sector primary care setting in Singapore. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2017. 61(5).

Belongia EA, et al. A community intervention trial to promote judicious antibiotic use and reduce penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae carriage in children. Pediatrics. 2001;108(3):575–83.

Sharifirad G, et al. A survey on the effects of husbands' education of pregnant women on knowledge, attitude, and reducing elective cesarean section. J Educ Health Promot. 2013;2:50.

Hasak JM, et al. Empowering post-surgical patients to improve opioid disposal: a before and after quality improvement study. J Am Coll Surg. 2018;226(3):235–240.e3.

Lawrence AE, et al. Effect of drug disposal bag provision on proper disposal of unused opioids by families of pediatric surgical patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2019:e191695.

Maughan BC, et al. Unused opioid analgesics and drug disposal following outpatient dental surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;168:328–34.

Rose P, et al. Opioid information pamphlet increases postoperative opioid disposal rates: a before versus after quality improvement study. Can J Anaesth. 2016;63(1):31–7.

Kliemann BS, et al. Socioeconomic determinants of antibiotic consumption in the State of Sao Paulo, Brazil: The Effect of Restricting Over-The-Counter Sales. PLoS One. 2016;11(12):e0167885.

Neighborhoods and Health. Second Edition ed. 2018: Oxford Scholarship.

Salihu HM, et al. Socio-ecological model as a framework for overcoming barriers and challenges in randomized control trials in minority and underserved communities. International journal of MCH and AIDS. 2015;3(1):85–95.

Pellmar TC, Brandt EN Jr, Baird MA. Health and behavior: the interplay of biological, behavioral, and social influences: summary of an Institute of Medicine report. Am J Health Promot. 2002;16(4):206–19.

Finch RG, et al. Educational interventions to improve antibiotic use in the community: report from the International Forum on Antibiotic Resistance (IFAR) colloquium, 2002. Lancet Infect Dis. 2004;4(1):44–53.

Beshears J, et al. Testimonials do not convert patients from brand to generic medication. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(9):e314–31.

Fuertes EI, et al. Trends in antibiotic utilization in Vancouver associated with a community education program on antibiotic use. Can J Public Health. 2010;101(4):304–8.

Cabral C, et al. How communication affects prescription decisions in consultations for acute illness in children: a systematic review and meta-ethnography. BMC Family Practice. 2014;15(1):63.

Grant S, et al. CONSORT-SPI 2018 Explanation and Elaboration: guidance for reporting social and psychological intervention trials. Trials. 2018;19(1):406.

Moe-Byrne T, et al. Behaviour change interventions to promote prescribing of generic drugs: a rapid evidence synthesis and systematic review. BMJ Open. 2014;4(5):e004623.

M., J., Information et informatisation en médecine générale. Inf.-G-Iciens. Namur (Belgium): Presses Universitaires de Namur; 1986. p. 193–209..

Kuehlein T, S.D., Visentin G, Gérvas J, Jamoulle M, Quaternary prevention: a task of the general practitioner. Prim Care, 2010. 10: p. 350.

Brodersen J, Schwartz LM, Woloshin S. Overdiagnosis: how cancer screening can turn indolent pathology into illness. Apmis. 2014;122(8):683–9.

Martins C, et al. Quaternary prevention: reviewing the concept. The European journal of general practice. 2018;24(1):106–11.

Baer RD, et al. Cross-cultural perspectives on physician and lay models of the common cold. Med Anthropol Q. 2008;22(2):148–66.

Eccles R. Is the common cold a clinical entity or a cultural concept? Rhinology. 2013;51(1):3–8.

Kahneman, D., Thinking, fast and slow. 2011: First edition. New York : Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011.

Zinn JO. 'In-between' and other reasonable ways to deal with risk and uncertainty: a review article. Health, risk & society. 2016;18(7-8):348–66.

Kaplan WA, et al. Policies to promote use of generic medicines in low and middle income countries: a review of published literature, 2000-2010. Health Policy. 2012;106(3):211–24.

Babar ZU, Kan SW, Scahill S. Interventions promoting the acceptance and uptake of generic medicines: a narrative review of the literature. Health Policy. 2014;117(3):285–96.

Malhotra S, et al. Effects of an e-Prescribing interface redesign on rates of generic drug prescribing: exploiting default options. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016;23(5):891–8.

Patel MS, et al. Using default options within the electronic health record to increase the prescribing of generic-equivalent medications: a quasi-experimental study. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(10 Suppl):S44–52.

Lorencatto F, et al. Driving sustainable change in antimicrobial prescribing practice: how can social and behavioural sciences help? J Antimicrob Chemother. 2018;73(10):2613–24.

Langdridge D, et al. A visual affective analysis of mass media interventions to increase antimicrobial stewardship amongst the public. Br J Health Psychol. 2019;24(1):66–87.

Davey P, et al. Interventions to improve antibiotic prescribing practices for hospital inpatients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;2:Cd003543.

Charani E, et al. Behavior change strategies to influence antimicrobial prescribing in acute care: a systematic review. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(7):651–62.

Craig P, et al. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50(5):587–92.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LL conceived of the study. LL developed the search string for analysis and contributed to piloting abstraction tools. LL and PA selected, reviewed, and coded the studies. EF or JH served as the third reviewer. LL wrote the first draft and revisions of the manuscript, and all authors commented on it and the subsequent drafts. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

There are no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1:.

Search Strategy

Additional file 2:.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Additional file 3:.

List of included studies

Additional file 4:.

Summary of quality assessment of included studies

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, L., Alam, P., Fearon, E. et al. Public target interventions to reduce the inappropriate use of medicines or medical procedures: a systematic review. Implementation Sci 15, 90 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-020-01018-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-020-01018-7