Abstract

Background

Influenza vaccination coverage remains low among health care workers (HCWs) in many health facilities. This study describes the social network defined by HCWs’ conversations around an influenza vaccination campaign in order to describe the role played by vaccination behavior and other HCW characteristics in the configuration of the links among subjects.

Methods

This study used cross-sectional data from 235 HCWs interviewed after the 2010/2011 influenza vaccination campaign at the Hospital Clinic of Barcelona (HCB), Spain. The study asked: “Who did you talk to or share some activity with respect to the seasonal vaccination campaign?” Variables studied included sociodemographic characteristics and reported conversations among HCWs during the influenza campaign. Exponential random graph models (ERGM) were used to assess the role of shared characteristics (homophily) and individual characteristics in the social network around the influenza vaccination campaign.

Results

Links were more likely between HCWs who shared the same professional category (OR 3.13, 95% CI = 2.61–3.75), sex (OR 1.34, 95% CI = 1.09–1.62), age (OR 0.7, 95% CI = 0.63–0.78 per decade of difference), and department (OR 11.35, 95% CI = 8.17–15.64), but not between HCWs who shared the same vaccination behavior (OR 1.02, 95% CI = 0.86–1.22). Older (OR 1.26, 95% CI = 1.14–1.39 per extra decade of HCW) and vaccinated (OR 1.32, 95% CI = 1.09–1.62) HCWs were more likely to be named.

Conclusions

This study finds that there is no homophily by vaccination status in whom HCWs speak to or interact with about a workplace vaccination promotion campaign. This result highlights the relevance of social network analysis in the planning of health promotion interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Although influenza vaccination is widely recommended to reduce the burden of influenza disease in patients and health care workers (HCWs), coverage remains low in many health facilities [1]. Many health promotion campaigns aimed at modifying health behaviors, such as influenza vaccination uptake, promote discussion among the subjects of the campaign. However, the results of fostering participation are not always in alignment with the campaign objective [2], for instance, increasing coverage. It is therefore interesting to consider how the health behavior in question affects the relations around the campaign. A suitable framework for this question is social network analysis (SNA) [3], a tool which is becoming increasingly popular in health-related issues [4] and has not been applied to vaccination campaigns in HCWs. There are increasing numbers of studies combining different types of social networks and health [5–7], with scope for possible network interventions [8]. In health care settings [9–11], these have been used to analyze hierarchies and positions in the network [12, 13], their relationship with hospitalization costs and readmission rates [14], information seeking [15, 16], the adoption of best practices [17], and homophily in advice and friendship networks, the tendency of individuals to associate and bond with similar others [18, 19]. Social networks may play a role in the adoption of health behaviors and practices [20], and homophily, in particular, has been shown to have an effect [21, 22]. The association between positions in the social network and decisions about vaccination [23] has been studied in parental vaccination decisions [24, 25], polio vaccine refusers [26], and high school [27] and medical students [28]. HCWs seem to be influenced by perceived pressure from colleagues to receive influenza vaccination [29]. To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the relationship between the influenza vaccination status and the social network of HCWs, defined by conversations around the campaign.

After three influenza vaccination campaigns for HCWs at the Hospital Clínic of Barcelona (HCB) that fostered participation [30, 31], the present study was conducted to describe to whom HCWs speak or interact with around a campaign. In particular, we assessed whether HCWs were more likely to discuss vaccination and the campaign with peers with the same vaccination behavior. In addition, given that vaccination is a behavior which is not easily visible, we assessed the perception of vaccination behavior that HCWs have about their peers.

Methods

Study design and setting

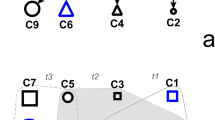

The HCB is organized in departments which comprise various medical services. In November 2010, we interviewed HCWs from two of the 15 HCB departments (A and B), which include four medical services, in order to establish the social network around that season’s influenza vaccination campaign. This cross-sectional study was presented to HCWs and their representatives beforehand to increase participation. The payroll list was used as an indicator of the number of staff in the two departments. Four trained interviewers repeatedly visited all wards of the two departments during all working shifts (morning/afternoon/night/weekends) for 2 weeks asking HCWs gave names of their colleagues in order to answer the questions. The interviewers wrote down the identification number of each HCW searched for in the hospital payroll list. HCWs interviewed or cited by another HCW became a node of the network. When a HCW, the sender, named another HCW, the receiver, this citation defined a link. This is a directed network that allowed senders to be distinguished from receivers in links. HCWs interviewed were included if they belonged to one of the two departments, if they answered at least one interview question, and when demographic data was complete in the human resources (HR) data file. Cited HCWs were included in the study if data was complete, even if they did not belong to either of the two departments. Links were considered valid if both sender and receiver were included.

Data sources and variables

We used three data sources. (1) The study survey. (2) Vaccination history from occupational health (OH) medical records. (3) HR data file.

-

1.

The study survey (see Additional file 1) included two questions. The first, used to generate the network, was “Who did you talk to or share some activity with respect to the seasonal vaccination campaign?” The promotion campaign included vaccination in the wards, group photos after vaccination, fostering of promotion among peers, and informative sessions. These were defined as activities, all of which were voluntary. HCWs interviewed were asked to provide some information about each link and the contents of conversations. The second question asked for the names of other HCWs who they knew had been vaccinated.

-

2.

The OH medical record included vaccination. HCWs not registered in the OH vaccination record were considered unvaccinated [32].

-

3.

Demographic characteristics (sex, date of birth, professional category, department, and positions of responsibility) were obtained from the HR data file. Concordance between variables was created by cross-matching the masked ID which identifies every HCB HCW.

In included nodes with complete data, the following data were collected. Vaccination status, sex, and positions of responsibility (heads of service and coordinators in all professional categories) were considered dichotomously. Age was measured in years. Professional category included five categories: staff physicians, resident physicians, nurses, auxiliary nurses and orderlies, and administrative and technical staff. Department was analyzed in three categories (A, B, and other).

Statistical methods

A descriptive analysis was made of the study population and the answers given. Qualitative variables were described using absolute frequencies and percentages, and quantitative variables using central trends, position, and dispersion by mean and standard deviation (SD). The social network was analyzed using exponential random graph models (ERGM) [33, 34] to assess how individual or shared characteristics influenced social links. ERGM are a class of exponential models that aims to predict the probability of a link between two nodes based on a set of individual and dyadic predictors of interest [35]. Sender and receiver characteristics were considered as individual predictors. Homophily for shared characteristics and mutuality (effect of reciprocal links) were considered as dyadic predictors. The baseline probability of a link is represented by an edges coefficient. Additional file 2: Table S1 contains a detailed description of all ERGM terms in our study. The analysis used R version 3.2.2 [36] and the Statnet library [37].

Results

A total of 310 HCWs were contacted, representing 82.4% of the payroll list (n = 376). Of these (Fig. 1), 45 refused to participate (85.5% participation rate). There were no significant differences in demographic characteristics between the payroll list and the HCWs included (Table 1). The 235 HCWs included in the analysis generated 521 links, resulting in 466 valid links and 341 nodes (see Additional file 3). Each HCW interviewed cited a mean of 1.98 HCWs (SD 1.45, median 2, max 8) and received a mean of 1.36 citations (SD 1.5, median 1, max 7) from other HCWs. Cited HCWs who had not been interviewed received a mean of 1.39 citations (SD 0.85, median 1). Of HCWs interviewed, 38 cited no one, 88 were not cited by anyone else, and 21 were neither cited nor cited anyone. Of the 319 links between interviewed HCWs, 114 (35.74%) were mutual (the opposite link was present).

ERGM analysis of the network involved a number of different models. Table 2 shows the coefficients of the selected models. The odds ratios (ORs) of the probability of a link are obtained by exponentiation. The following ORs are taken from model 4. Homophily was significant for professional category (OR 3.13, 95% CI = 2.61–3.75), sex (OR 1.34, 95% CI = 1.09–1.62), age (OR 0.7, 95% CI = 0.63–0.78 per decade of difference), and department (OR 11.35, 95% CI = 8.17–15.64) but not for vaccination status (OR 1.02, 95% CI = 0.86–1.22), even in the simplistic model considering homophily by vaccination status alone (OR 0.94, 95% CI = 0.78–1.13). This means that, given two nodes, the OR of a link increased when the two nodes shared a category other than vaccination status. The sender effect was significant for staff physicians (OR 0.69, 95% CI 0.50–0.94) and nurses (OR 0.61, 95% CI 0.47–0.78), meaning that they were less likely to cite someone in the survey with respect to the “other” category. A vaccinated HCW was more likely to be named by their peers than a non-vaccinated HCW (OR 1.33, 95% CI 1.09–1.62) when all other factors were kept constant. Vaccinated HCWs were not significantly more likely to be sources of links (OR 1.12, 95% CI 0.92–1.37). The receiver effect of the variable age was significant (OR 1.26, 95% CI = 1.14–1.39 per extra decade of receiver HCW) as was the sender effect (OR 0.82, 95% CI 0.74–0.9 per extra decade of sender HCW). In all models used, mutuality had the largest effect and was always significant (OR 38.74, 95% CI 27.03–55.59). Fit diagnostics were checked for all the models included in Table 2 (see Additional file 4) and no indication of degeneracy was found.

When asked to provide additional information about the reported relations, 86.48% of the 466 links were general comments about the campaign, 19.53% were joint participation in campaign activities, 8.8% reported having issued a recommendation (we did not register the sense), and 11.59% reported having received a recommendation. People stated they had known each other, on average, for 6.48 (SD 6.82) years. The frequency of meetings was daily (81.97%), weekly (15.67%), or monthly (2.36%). The topics usually discussed with the link were work (98.5%), personal affairs (79.4%), leisure activities (79.4%), and news (73.18%).

With respect to the second question on the perception of the vaccination status of their colleagues, 122 HCWs (51.91% of those interviewed) cited at least one other HCW they thought was vaccinated, and 94 of these (77.05%) cited only vaccinated HCWs. The positive predictive value (PPV) (percentage of cited HCWs who were actually vaccinated) was 86%.

Discussion

We studied the influenza vaccination of HCWs and the social network defined by conversations around a vaccination campaign. A major finding is that similarity in vaccination behavior did not play a significant role in the probability of naming another HCW in our hospital. Links were more likely when individuals shared a professional category, sex, age, or department. In addition, some characteristics influenced participants citing more HCWs (being younger, having a position of responsibility, some professional categories) and others which increased the likelihood of being cited as a link (being vaccinated).

The lack of homophily according to vaccination behavior, also described for influenza vaccination in a friendship network of medical students [28], contrasts with other studies of advice networks in parental vaccination decisions [24–26] and in a contact network of influenza vaccination in high school students [27], where homophily by vaccination status was observed. The differences between our findings and those of other reports may be due to two reasons. First, different types of networks may yield different answers to the question of homophily by vaccination status. In contact networks, which are closely related to the spread of the virus, homophily by vaccination behavior may ultimately lead to the formation of unvaccinated clusters and thus reduce herd immunity [27, 38]. Advice-seeking, discussion (such as ours), and even friendship networks are probably more dependent on the cultural context, the type of vaccine or disease, and, in the case of HCWs, corporate culture. Both types of networks are interdependent, and, in the case of communicable diseases, social reinforcement of positive and negative opinions around vaccination [11] may increase the possibility of outbreaks through the spread of negative opinions about vaccination [39, 40]. Secondly, our study took into account homophily by other factors than those considered in other studies. In this respect, we would like to emphasize that the lack of homophily was observed even in the simplest model, which included only the homophilic effect by vaccination status. Homophily by professional category, age, or department has been reported in advice and friendship networks [18, 19]. Older and vaccinated HCWs were more frequently cited. This may indicate a pattern of professionals who are more often asked for advice or whose conversations are more frequently recalled. The seniority factor has also been observed in other studies [11, 12, 19].

The main limitation of the study is due to the cross-sectional design, which does not allow inferential conclusions on the impact of the campaigns to be drawn. The names of the two departments remain confidential but the results seem representative of the whole hospital since there were no significant differences in the study variables with the payroll list [31]. Services directly related to infectious diseases and infection control were avoided. In contrast with other behaviors or conditions, such as overweight and smoking, influenza vaccination could remain invisible to peers. Ideally, a question about the perception of the vaccination status of the HCWs named should have been included, but this could have compromised participation in the study. A separate question was thus added as a quality control, and a satisfactory PPV was obtained. A strength of the study is that it avoided sampling. The recruitment rate of 82.4% of the total payroll list, which included workers on leave and vacation and part-timers, is a good reflection of the entire workforce, given that interviewers repeatedly visited all wards and all shifts until no new HCW was found. Participation was also high. The reported mutuality of 35.7% is not high but is comparable to other studies of advice and discussion network [13, 16, 41, 42]. This rate is an indication that many conversations between two interviewed HCWs that actually occurred were only reported by one of them. A possible approach would be to treat this inconsistency as a reporting error and incorporate it into the model [41]. However, we decided not to symmetrize the network because we consider that the fact of recalling and reporting a conversation by a HCW may be of importance in their decision making, independently of whether it is also recalled by the target HCW. Caution should be taken about the generalization of the results on homophily, since they are closely related to the cultural and corporate contexts and we believe that the present study is an illustration of the relevance of SNA in the assessment and planning of health promotion campaigns aiming at peer-to-peer interaction.

This study is a first approach to the use of SNA as a tool in vaccination campaigns. From the perspective of health promotion, especially when aimed at participation, two situations that should be avoided may be detected by SNA. First, if health behaviors are grouped in closed communities, strategies to increase communication between peers can reinforce the beliefs of individuals in each group by reducing exposure to different points of view. Homophily due to factors other than health behavior may increase the exposure of individuals to diverse opinions and help changes in the behavior to spread more successfully [21]. Secondly, individuals opposed to the recommendations of the program may be more active in the network and have a higher probability of influencing others’ views, as has been reported in some online social networks [40]. Neither of these two possibilities was observed in our study. Since fostering participation has the risk that individuals issue messages that differ from the recommendations, SNA may be a useful tool for the assessment of the role played by a health behavior in a group and could shed light on the design, implementation, and evaluation of a health promotion campaign, which should be validated. In this social network, for example, messages could be tailored by professional category or strategies to foster communication among different professional categories could be implemented. Due to the lack of homophily by vaccination behavior, vaccine promotion actions aimed at fostering communication among HCWs should be continued. More research is needed to clarify situations in which the influenza vaccination status might be a homophilic factor in this kind of social network of HCWs.

Conclusions

This study defines to whom HCWs relate in the context of a vaccination promotion campaign and shows that, in this social network, there is no homophily by vaccination status. Analysis of the social network of conversations around a health topic highlights the existing channels of communication and the relevance of the health behavior in the configuration of links.

Abbreviations

- AIC:

-

Akaike Information Criterion

- BIC:

-

Bayesian Information Criterion

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- ERGM:

-

Exponential random graph model

- HCB:

-

Hospital Clínic de Barcelona

- HCW:

-

Health care worker

- HR:

-

Human resources

- OH:

-

Occupational health

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SNA:

-

Social network analysis

References

Rashid H, Yin JK, Ward K, et al. Assessing interventions to improve influenza vaccine uptake among health care workers. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(2):284–92. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1087.

Laverack G. The pocket guide to health promotion. UK: McGraw-Hill Education; 2014.

Scott J. Social network analysis. 3rd ed. UK: Sage Publishing; 2012.

Valente TW. Social networks and health. UK: Oxford University Press; 2010.

Luke DA, Harris JK. Network analysis in public health: history, methods, and applications. Annu Rev Public Health. 2007;28:69–93.

Smith K, Christakis N. Social networks and health. Annu Rev Sociol. 2008;34:405–29. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.34.040507.134601.

Sales AE, Estabrooks CA, Valente TW. The impact of social networks on knowledge transfer in long-term care facilities: protocol for a study. Implement Sci. 2010;5:49. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-49.

Valente TW. Network interventions. Science. 2012;337:49–53. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1217330.

Chambers D, Wilson P, Thompson C, et al. Social network analysis in healthcare settings: a systematic scoping review. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e41911. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0041911.

Dunn AG, Westbrook JI. Interpreting social network metrics in healthcare organisations: a review and guide to validating small networks. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72(7):1064–8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.01.029.

Cunningham FC, Ranmuthugala G, Plumb J, et al. Health professional networks as a vector for improving healthcare quality and safety: a systematic review. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21(3):239–49. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2011-000187.

Boyer L, Belzeaux R, Maurel O, et al. A social network analysis of healthcare professional relationships in a French hospital. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2010;23(5):460–9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/09526861011050501.

Wensing M, van der Eijk M, Koetsenruijter J, et al. Connectedness of healthcare professionals involved in the treatment of patients with Parkinson’s disease: a social networks study. Implement Sci. 2011;6:67. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-6-67.

Uddin S, Hossain L, Hamra J, et al. A study of physician collaborations through social network and exponential random graph. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:234. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-13-234.

Keating NL, Ayanian JZ, Cleary PD, et al. Factors affecting influential discussions among physicians: a social network analysis of a primary care practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:794–8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11606-007-0190-8.

Wensing M, van Lieshout J, Koetsenruiter J, et al. Information exchange networks for chronic illness care in primary care practices: an observational study. Implement Sci. 2010;5:3. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-3.

Mascia D, Cicchetti A, Damiani G. ‘Us and Them’: a social network analysis of physicians’ professional networks and their attitudes towards EBM. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:429. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-13-429.

Ariño JM, Torrent MS. Las redes sociales del Centro de Salud San Pablo de Zaragoza. Aten Primaria. 2009;41:670–4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.aprim.2009.03.012.

Mascia D, Di Vincenzo F, Iacopino V, et al. Unfolding similarity in interphysician networks: the impact of institutional and professional homophily. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:92. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-0748-9.

Jippes E, Achterkamp MC, Brand PLP, et al. Disseminating educational innovations in health care practice: training versus social networks. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70:1509–17. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.12.035.

Centola D. An experimental study of homophily in the adoption of health behavior. Science. 2011;334:1269–72. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1207055.

Schaefer DR, Simpkins SD. Using social network analysis to clarify the role of obesity in selection of adolescent friends. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:1223–9. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301768.

Parker AM, Vardavas R, Marcum CS, et al. Conscious consideration of herd immunity in influenza vaccination decisions. Am J Prev Med. 2013;45:118–21. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2013.02.016.

Brunson EK. The impact of social networks on parents’ vaccination decisions. Pediatrics. 2013;131(5):e1397–404. http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-2452.

Bults M, Beaujean DJMA, Richardus JH, et al. Pandemic influenza A (H1N1) vaccination in The Netherlands: parental reasoning underlying child vaccination choices. Vaccine. 2011;29(37):6226–35. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.06.075.

Onnela J-P, Landon BE, Kahn A-L, et al. Polio vaccine hesitancy in the networks and neighborhoods of Malegaon, India. Soc Sci Med. 2016;153:99–106. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.01.024.

Barclay VC, Smieszek T, He J, et al. Positive network assortativity of influenza vaccination at a high school: implications for outbreak risk and herd immunity. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e87042. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0087042.

Edge R, Heath J, Rowlingson B, et al. Seasonal influenza vaccination amongst medical students: a social network analysis based on a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0140085. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0140085.

Baron G, De Wals P, Milord F. Vaccination practices of Quebec family physicians. Influenza vaccination status and professional practices for influenza vaccination. Can Fam Physician. 2001;47:2261–6.

Llupià A, García-Basteiro AL, Olivé V, et al. New interventions to increase influenza vaccination rates in health care workers. Am J Infect Control. 2010;38(6):476–81. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2010.01.013.

Llupià A, Mena G, Olivé V, et al. Evaluating influenza vaccination campaigns beyond coverage: a before-after study among health care workers. Am J Infect Control. 2013;41:674–8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2013.04.006.

Llupià A, García-Basteiro AL, Mena G, et al. Vaccination behaviour influences self-report of influenza vaccination status: a cross-sectional study among health care workers. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e39496. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0039496.

Robins G, Snijders T, Wang P, et al. Recent developments in exponential random graph (p*) models for social networks. Soc Networks. 2007;29(2):192–215. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2006.08.003.

Robins G, Pattison P, Kalish Y, et al. An introduction to exponential random graph (p*) models for social networks. Soc Networks. 2007;29(2):173–91. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2006.08.002.

Morris M, Handcock MS, Hunter DR. Specification of exponential-family random graph models: terms and computational aspects. J Stat Softw. 2008;24(4):1548–7660.

R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL http://www.R-project.org/. R Found. Stat. Comput. Vienna, Austria. 2013.

Handcock MS, Hunter DR, Butts CT, et al. Statnet: software tools for the representation, visualization, analysis and simulation of network data. J Stat Softw. 2008;24:1–11.

Ndeffo Mbah ML, Liu J, Bauch CT, et al. The impact of imitation on vaccination behavior in social contact networks. PLoS Comput Biol. 2012;8(4):e1002469. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002469.

Campbell E, Salathé M. Complex social contagion makes networks more vulnerable to disease outbreaks. Sci Rep. 2013;3:1905. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/srep01905.

Salathé M, Vu DQD, Khandelwal S, et al. The dynamics of health behavior sentiments on a large online social network. EPJ Data Sci. 2013;2:1–12. http://dx.doi.org/10.1140/epjds16.

Potter GE, Smieszek T, Sailer K. Modeling workplace contact networks: the effects of organizational structure, architecture, and reporting errors on epidemic predictions. Netw Sci. 2015;3:298–325. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/nws.2015.22.

Creswick N, Westbrook JI, Braithwaite J. Understanding communication networks in the emergency department. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:247. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-9-247.

Acknowledgements

We thank all Hospital Clínic of Barcelona workers who participated in the study. We thank the interviewers (Xavier L. Llauradó, Consol Llupià, Maya Ninova, and Elisa Salas) and the project support staff (María Isabel Gómez) for their professionalism. We thank the two reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions. We thank David Buss for the technical help.

Funding

This study was funded by the Solvay-Abbott Influenza Research Grant 2010. J Puig is funded by MTM2015-65715-P. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The investigators were contracted by their institutions.

Availability of data and materials

The database with the network of the study is included within the article (Additional file 4) with some deleted characteristics for the sake of confidentiality.

Authors’ contributions

AL, JP, and GM designed the study. AL and JP and drafted the manuscript. JP and AL analyzed the data. All the authors contributed to the interpretation of the data and revision of the manuscript. AL had primary responsibility for final content and acts as guarantor. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

JMB has received fees for lectures, advice, and participation in working groups funded by the pharmaceutical industry. He has participated as principal investigator in clinical trials of vaccines (influenza vaccines and others) promoted by GlaxoSmithKline and Sanofi Pasteur MSD. All other authors declare they have no competing interests. No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All study materials stated that the study was approved by the HCB Clinical Research Ethics Committee and that participation was voluntary. All participants gave informed consent. In accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, all personal HCW data were dissociated and treated as confidential at all times. For confidentiality, the names of the departments involved remain anonymous.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Survey. (DOCX 19 kb)

Additional file 2: Table S1.

Interpretation of the coefficients of ERG models. (DOCX 12 kb)

Additional file 3:

Study survey. (GRAPHML 63 kb)

Additional file 4:

Fit diagnostics of ERGM models. (DOCX 775 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Llupià, A., Puig, J., Mena, G. et al. The social network around influenza vaccination in health care workers: a cross-sectional study. Implementation Sci 11, 152 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-016-0522-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-016-0522-3