Abstract

Background

Selecting for drought tolerance in urban tree species can have a significant influence on survival rates, aftercare requirements and performance. The water potential at turgor loss point (πtlp) is gaining popularity as a trait to help determine drought tolerance to aid tree selection. Therefore, it is important to understand if differing methods used to measure or calculate πtlp deliver consistent results.

Results

The sensitivity of three methods used to determine this valuable selection parameter were evaluated. A classical pressure chamber, pressure–volume (P–V) curve method was compared with vapour-pressure osmometer (Vapro®) and dewpoint hygrometer (WP4C) methods. These methods were evaluated using closely related cultivars of Acer platanoides and A. pseudoplatanus ‘Negenia’.

Conclusion

Both the osmometer and hygrometer methods ranked genotypes with a very high similarity (Rs = 1, R2 = 0.96) and were able to identify significant differences between cultivars. This is the first study to demonstrate suitability of the dewpoint hygrometer in comparison to the vapour-pressure osmometer to measure πtlp. The P–V method was unable to identify differences between the cultivars tested. The Vapro and WP4C provide greater applicability than the conventional P–V method to studies requiring both high throughput and high sensitivity. Consistency of measurement type is however highly recommended in future studies as some differences were observed between Vapro and WP4C.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Trees within the urban environment often experience abiotic stresses [1,2,3]; that in-turn, can increase susceptibility to pest and diseases [4]. Selecting for drought tolerance in urban tree species can have a significant influence on survival rates, aftercare requirements and future aesthetic and environmental benefits [5,6,7]. Tree selection is often focused on aesthetic characteristics [8], however, when tolerance is considered it is often based on personal experience and observation. Data from plant-use literature and scientific studies is frequently inconsistent between sources and often lacks specificity [5, 9]. Increases in the frequency and severity of drought events are expected as a result of climate change [10,11,12]. Informed tree selection based on physiological or genetic drought tolerance traits is therefore increasingly desirable, facilitating selection for current and future environmental demands [13]. Foliar physiological traits are gaining popularity as they can determine physiological drought tolerance as opposed to drought avoidance strategies [5]. Genotypes which avoid drought may shed leaves or branches in response to drought stress or rely on extensive root systems to gather water [14, 15], these strategies are not desirable for urban sites. Urban tree selection is clearly more nuanced than simply consideration of functional traits; however, improvements to current tolerance information is essential to aid and encourage appropriate selection [16]. One physiological trait capable of identifying drought tolerance is the measurement of leaf water potential at wilting or turgor loss (πtlp) [17, 18]. This trait is capable of characterising intraspecific drought tolerance [5]. Techniques are now available to increase the speed of this measurement [19] facilitating ecological scale studies [20] and studies to aid appropriate tree selection between and within genera [5, 9, 21]. Therefore, a range of approaches are currently being used to determine πtlp. However, no study has evaluated the sensitivity of these alternative methods among closely related cultivars. In this study, the so-called direct measurements, using a vapour-pressure osmometer and dewpoint hygrometer to measure water potential are compared with a classical pressure–volume (P–V) curve method, measured on adjacent leaves. In this study, closely related genotypes are used to allow the sensitivity of measurement method to be evaluated.

P–V curves are the classical method of inferring a range of plant-water relation parameters [22] and can provide information on genotypic drought tolerance using the parameter πtlp [18, 23, 24]. A more negative πtlp lengthens the functional range of foliar water potential [25] and is thought to be achieved by a combination of osmotic adjustment (solute accumulation to increase cell hydration) and elastic adjustment (decreasing the point at which turgor loss occurs) [26, 27]. πtlp is now considered the dominant determining factor of drought tolerance [18, 27]. The production of P–V curves has one significant disadvantage; they are time-consuming to produce, meaning adequately large scale studies and genetic screening are impractical [26, 28, 29]. Additionally, despite P–V curves being widely regarded as the classical method for determining water relation parameters, the comparative accuracy between methods has been frequently criticised [30, 31]. Warranting further studies investigating alternative methods of measuring water potential (Ѱ) in plant tissue [28, 32, 33].

Direct measurements (vapour-pressure osmometer and dewpoint hygrometer), are rapid methods used to determine water potential [28]. The dewpoint hygrometer (such as the WP4C, decagon devices Inc. München, Germany) uses the chilled-mirror dewpoint technique [34] measuring water potential from zero to − 300 MPa on ca. 35 mm diameter leaf discs [35, 36]. The dewpoint hygrometer measures the sum of osmotic and matric potential; it has been used successfully on leaves of tobacco and ivy [35] and flowers of slipper orchid [37]. Relative difference between dewpoint hygrometer and pressure chamber measurements of water potential have been shown to be very similar (R2 = 0.84) [33]. The vapour-pressure osmometer (Vapro®, Wescor, Logan UT, USA) measures solute concentration (osmolality) which can be converted to water potential using the Van’t Hoff equation (Eq. 1); it can measure leaf discs of ca. 8 mm diameter [20, 28] or expressed sap [28, 38]. Callister et al. [28] show osmometer osmotic potential (π) measurements of expressed sap are comparable with those of parallel π pressure chamber readings. Bartlett et al. [19] show that measurements of π on rehydrated freeze-thawed leaf discs can rapidly determine the osmotic potential at full rehydration or full turgor (π0). Bartlett et al. [19] also demonstrated that π0 correlates to the πtlp. They used vapour-pressure osmometer measurements taken from plants which had pressure chamber derived P–V curves, determined within 4 weeks of each other, for sixteen species. However, for fourteen additional species, the P–V curves had been calculated within the previous 2 years [19]. Significant adjustment of πtlp is known to occur across a single season [5]; however, additional meta-analysis has also shown a good correlation between π0 and πtlp [18], adding further validity to the measurement despite potential issue with the timing of the initial data collection. Sufficient evidence now exists to warrant large scale evaluations of πtlp, calculated from π0, using a vapour-pressure osmometer [5, 9, 20, 21]. However, it is not yet clear if a dewpoint hygrometer can be used to evaluate πtlp. Therefore, this study aims to evaluate the accuracy of osmometer and hygrometer measurements in direct parallel to P–V curves using very closely related Acer genotypes.

Method

Plant material

Thirty-two seven-year-old, 4 m tall trees were used for this experiment arranged across three completely randomized linear rows. The following Acer genotypes were measured during this trial: A. platanoides ‘Drummondii’, A. p. ‘Emerald Queen’, A. p. ‘Royal Red’, A. p. ‘Princeton Gold’ and A. pseudoplatanus ‘Negenia’. All measured cultivars were grafted onto their respective species-type rootstocks. Trees were potted during the winter of 2013/14 and grown at Barcham Trees nursery, Ely, Cambridgeshire, UK (52.366923°N, 0.315864°W) prior to being planted outside in March 2017 at the Bartlett Tree Research laboratory, Shinfield, Reading, Berkshire, UK (51.412393°N, − 0.937909°W). Encircling roots were cut on all trees to aid establishment during the planting process. Trees were arranged across three rows, each measured cultivar was randomized within each row.

Sample preparation

Two visually healthy leaves were removed ca. 30 cm below a terminal bud on the lower limb (ca. 2 m high) of each tree; opposite leaves were selected to ensure the closest similarity in physiological age. Leaves were collected between 16:00 and 17:00 on the 24th July to the 9th of August 2017. Leaves were removed from the tree by snapping at the axil union and immediately returned to the laboratory (within < 2 min). In the laboratory, leaves were immediately weighed and petioles re-cut underwater (ca. 1 cm away from the petiole base), petioles and cut petiole portions were left in water to fully hydrate in the dark for ca. 12 h. Hydrating leaves were left in an insulated container during this time kept near 100% relative humidity [average vapour-pressure deficit [39] equalled 0.01 (± 0.03)]. Individual, fully hydrated leaves were removed from the container, patted dry and immediately weighted and processed using either the pressure chamber P–V curve method or direct methods.

Pressure–volume curves

Pressure–volume curves were calculated in accordance with the sap expression method; the method was similar to that used by Parker and Pallardy [31]. Whole undamaged leaves were sealed inside a pressure chamber (model 600D, PMS instruments Co., Albany, USA) with a piece of damp filter paper to reduce water loss. The average initial balance pressure was − 0.13 MPa (± 0.007). Leaves which did not hydrate to an initial Ѱ of > − 0.2 MPa were discarded [25]. Incremental pressures of 0.2 MPa were applied to the leaf, beginning at 0.2 MPa. P–V curves were halted at − 2.4 MPa or when greater than three data points were in the linear portion of the graph. Total expressed sap at each pressure was absorbed in pre-weighed 1.5 ml Eppendorf tubes filled with dry low-lint absorbent tissue paper (Kimtech Science, Kent, UK). Tubes were handled and opened for the minimum possible time during sap collection to prevent evaporation. Leaves were weighed immediately following the final measurement, facilitating determination of the average uncollected water (4.7%). Leaves were then dried for > 48 h at 60 °C. P–V curves were plotted as 100-RWC (relative water content) (D) on the x axis, against − 1/MPa (y axis). Overhydration, or plateau effects were corrected where appropriate in accordance with the method described by [40]. Water potential at the turgor loss point (πtlp) was calculated based on a method developed by Schulte and Hickley [41], obtained from: landflux.org/resources/PV_Curve_Fitting_5.6.xls. This method has also been used by [42,43,44] (Fig. 1).

Direct measurements

Two leaf discs, 35 mm and 8 mm diameter, (dewpoint hygrometer and vapor pressure osmometer respectively) were taken between the mid-rib and margin on the lower quartile of the opposing leaf used in the P–V curve. Leaf discs were foil wrapped and submerged in liquid nitrogen. Prior to the measurement, leaf discs were punctured 10–15 times with sharp-tipped forceps to improve equilibration times [19].

Dewpoint hygrometer (WP4C, decagon devices Inc. München, Germany) measurements were taken with the device in its continuous mode, connected to the AquaLink data logging software (decagon devices) on a laptop computer. One measurement per leaf was recorded when values became stable (ca. 15–20 min.). Stability was assessed graphically for each leaf disc. The WP4C measures total water potential which is the sum total of gravitational, matric, osmotic and pressure potentials. In freeze thawed leaf discs it is putatively assumed that gravitational, matric and pressure potentials are all zero or negligible, therefore, in this study, osmotic potential is the considered component.

Osmometer measurements were taken with a vapour pressure osmometer (Vapro 5600, Wescor, Logan UT, USA) using the standard 10 µl chamber. Measurements were made in accordance with the method detailed by Sjöman et al. [9].

For measurements made using the Osmometer, solute concentration (mmol kg−1) was converted to water potential using Van ‘t Hoff’s equation:

Equation 1 Van ‘t Hoff equation, where C is the molar solute concentration (mmol kg−1), R is the universal gas constant (8.3144598E−0.6) in m3 MPa K−1 mol−1, T is the temperature (K) [45].

Dewpoint hygrometer and vapor pressure osmometer are hereafter referred to as WP4C and Vapro for simplicity.

Both direct measurements of osmotic potential (π) were converted into predicted P–V value (\(\hat{\pi }_{pv}\)) using the equation determined by Bartlett et al. [19] (Eq. 2).

Equation 2 conversion from osmometer measurement (π) to predicted P–V (\(\hat{\pi }_{pv}\)) measurement [19].

πtlp was calculated from π0 using the regression equation adapted for temperate species by Sjöman et al. [5] originally calculated from Additional file 1 published by [18].

Equation 3 Adapted equation facilitating prediction of πtlp (ѰP0) from osmometer π0 (Ѱπ100) (R2 = 0.91) (notation in parentheses is the notation used by Sjöman et al. [5]. The notation used here correspond to Bartlett et al. [18].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GenStat 17th edition. Following tests for normality, analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to test for differences between means. Linear regression (R2) and Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (rs) was also calculated in order to describe the relationship between readings. Post-hoc analysis was performed using a Tukey’s 95% confidence interval.

Results

A significant effect of both genotype and measurement method (p ≤ 0.001 for both) was observed. However, a significant interaction between genotype (cultivar) and method was observed following a two-way ANOVA (p ≤ 0.001). Data was therefore compared overall with cultivars nested within measurement method.

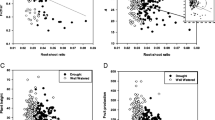

Similarities between measurements was determined using a correlation coefficient (R2) and Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (Rs). P–V measurements were excluded from correlation comparisons as no significant differences were discovered between cultivars. The Vapro and WP4C provided the same rank (Rs = 1) and highly similar correlation coefficient (R2 = 0.96). Values of π0 provided the same comparative ranking as πtlp.

Correcting measurements using Eq. 2 is highly important, especially if values are to be compared against P–V curve data. Equation 2 improved similarity to P–V curves by an average of ca. 5% for both Vapro and WP4C. However, in this study significant and species-specific differences occurred with both devices when compared to the P–V method (Fig. 2).

Showing πtlp for each method, Vapro and WP4 are reported as πtlp (P–V) following conversion using Eq. 2. Error bars show standard error. Letters denote significant differences (Duncan multiple range test) between cultivars nested in method at the 95% confidence interval. A. platanoides ‘Drummondii’, A. p. ‘Emerald Queen’, A. p. ‘Royal Red’, A. p. ‘Princeton Gold’ and A. pseudoplatanus ‘Negenia’. Between species analysis for each measurement method p ≤ 0.001 for Vapro and WP4C, p = 0.938 for P–V πtlp

Discussion

In this study, the pressure chamber pressure–volume (P–V) curve method was unable to identify significant differences between the closely related cultivars tested (p = 0.938). However, both direct measurements tested (WP4C and Vapro), identified highly significant differences between cultivars (p ≤ 0.001). This is the first study to our knowledge to demonstrate the suitability of the dewpoint hygrometer (WP4C) in comparison to the P–V curve and vapour-pressure osmometer (Vapro) methods when measuring πtlp. Significant differences between measurement methods were present for all cultivars except A. pseudoplatanus ‘Negenia’ (p = 0.092) and A. platanoides ‘Princeton Gold’ (p = 0.112) despite the use of the correction factor described by Bartlett et al. [19] (Eq. 3). No difference in rank however was observed between the WP4C and Vapro (Rs = 1). The Vapro returned results comparably closer to those from P–V curves. The Vapro and WP4C differed from P–V values at an average 0.04 MPa (± 0.055) and 0.20 MPa (± 0.057) respectively, these differences are not however thought to be practically significant for species selection. Therefore, either device can be utilised for tolerance studies.

As suggested by Zhang et al. [37] and Martínez et al. [33] more negative values (average − 26.5%, without correction, Eq. 3) were observed using both devices in comparison to the pressure chamber. Many theories exist to explain why thermocouple and hygrometer devices measure more negatively than pressure chambers, including water loss during leaf excision as well as active accumulation of solutes by neighbouring undamaged tissue [33, 46]. Zhang et al. [37] however, also discuss simply that the measurement is of the air above the sample, thus a more negative Ѱ is returned. It is however imperative that the air above the sample is in equilibration with the sample, consequently we assume Zhang et al. [37] discussion is based on the assumption that losses in water potential may occur in locations where sample water potential is more negative than ambient humidity. Therefore, a decrease in sample water potential would occur in order to reach equilibration. If this was the case, more negative values would be expected from the WP4C owing to the greater leaf to chamber volume (0.27 mm3 ml−1 vs 2.3 mm3 ml−1 for WP4C and Vapro respectively); in this trial this did not occur.

In some circumstances, utilisation of the Vapro device can be recommended; the larger leaf disc size required by the WP4C, reduces the ability to evaluate plants with smaller or more complex leaf areas without adaptation of the method. Previous studies have also utilised the Vapro to evaluate relatively large genotypic selection [5, 9, 21]. In future studies, we recommend a process of cross calibration with previous studies using species in common in order to place genotypes within the drought tolerance continuum.

Conclusion

The Vapro and WP4C provide greater applicability than the conventional P–V method to studies requiring high throughput and high sensitivity. Data presented here reveals the sensitivity of the vapour-pressure osmometer and dewpoint hygrometer methods to measure πtlp characterising the drought tolerance of closely related genotypes. Data identifies no difference in rank between results from both WP4C and Vapro. Some significant differences were however observed between Vapro and WP4C (Fig. 2) therefore consistency of measurement type is recommended in future studies. Poor sensitivity was observed when using the P–V method, therefore, future studies should utilise either the vapour-pressure osmometer or dewpoint hygrometer in order to provide rapid and sensitive genotypic drought tolerance quantifications.

Abbreviations

- πtlp :

-

water potential at turgor loss point

- π:

-

osmotic potential

- π0 :

-

osmotic potential at full rehydration or full turgor

- Ψ:

-

water potential

- Rs :

-

Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient

- P–V:

-

pressure volume

- \(\hat{\pi }_{pv}\) :

-

predicted pressure–volume osmotic potential

References

Gibbs JN, Palmer CA. A survey of damage to roadside trees in London caused by the application of de-icing salt during the 1990/91 winter. Arboric J. 1994;18:321–43.

Jim CY. Physical and chemical properties of a Hong Kong roadside soil in relation to urban tree growth. Urb Ecosyst. 1998;2:171–81.

Scharenbroch BC, Carter D, Bialecki M, Fahey R, Scheberl L, Catania M, et al. A rapid urban site index for assessing the quality of street tree planting sites. Urb Urb Green. 2017;27:279–86.

Cregg B, Dix ME. Tree moisure stress and insect damage in urban areas in relation to heat island effects. J Arboric. 2001;27:8–17.

Sjöman H, Hirons AD, Bassuk NL. Urban forest resilience through tree selection-Variation in drought tolerance in Acer. Urb Urb Green. 2015;14:858–65.

Bassuk N, Curtis D, Marranca B, Neal B. Recommended urban trees: site assessment and tree selection for stress tolerance. Ithaca, NY: Urban Horticulture Institute, Cornell University; 2009.

Roman LA, Battles JJ, McBride JR. Determinants of establishment survival for residential trees in Sacramento County. CA. Landsc Urb Plan. 2014;129:22–31.

Vaz Monteiro M, Doick KJ, Lawrence V, Albertini A, Handley P. Investigation into the drought tolerance of broadleaf street trees using chlorophyll fluorescence. Acta Hortic. 2017;1189:427–30.

Sjöman H, Hirons AD, Bassuk NL. Magnolias as urban trees—a preliminary evaluation of drought tolerance in seven magnolia species. Arboric J. 2018;40:47–56.

IPCC. Climate change 2007: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability: working Group II contribution to the Fourth Assessment Report of the IPCC Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Work Gr II Contrib to Intergov Panel Clim Chang Fourth Assess Rep. 2007;2007(1):976.

Bartlett MK, Zhang Y, Kreidler N, Sun S, Ardy R, Cao K, et al. Global analysis of plasticity in turgor loss point, a key drought tolerance trait. Ecol Lett. 2014;17:1580–90.

Pflug EE, Buchmann N, Siegwolf RTW, Schaub M, Rigling A, Arend M. Resilient leaf physiological response of European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) to summer drought and drought release. Front Plant Sci. 2018;9:187.

Cattivelli L, Rizza F, Badeck F-W, Mazzucotelli E, Mastrangelo AM, Francia E, et al. Drought tolerance improvement in crop plants: an integrated view from breeding to genomics. Field Crop Res. 2008;105:1–14.

Mauseth JD. Botany: an introduction to plant biology. 4th ed. Burlington: Jones & Bartlett; 2011.

Hirons AD, Thomas PA. Environmental challenges for trees. Applied tree biology. Chichester: Wiley; 2018. p. 351–89.

Desclaux D, Huynh TT, Roumet P. Identification of soybean plant characteristics that indicate the timing of drought stress. Crop Sci. 2000;40:716–22.

Sack L, Cowan PD, Jaikumar N, Holbrook NM. The ‘hydrology’ of leaves: co ordination of structure and function in temperate woody species. Plant Cell Environ. 2003;26:1343–56.

Bartlett MK, Scoffoni C, Sack L. The determinants of leaf turgor loss point and prediction of drought tolerance of species and biomes: a global meta-analysis. Ecol Lett. 2012;15:393–405.

Bartlett MK, Scoffoni C, Ardy R, Zhang Y, Sun S, Cao K, et al. Rapid determination of comparative drought tolerance traits: using an osmometer to predict turgor loss point. Methods Ecol Evol. 2012;3:880–8.

Maréchaux I, Bartlett MK, Sack L, Baraloto C, Engel J, Joetzjer E, et al. Drought tolerance as predicted by leaf water potential at turgor loss point varies strongly across species within an Amazonian forest. Funct Ecol. 2015;29:1268–77.

Sjöman H, Hirons AD, Bassuk NL. Improving confidence in tree species selection for challenging urban sites: a role for leaf turgor loss. Urb Ecosyst. 2018;21:1171–88.

Tyree MT, Hammel HT. The measurement of the turgor pressure and the water relations of plants by the pressure-bomb technique. J Exp Bot. 1972;23:267–82.

Jane GT, Green TGA. Utilisation of pressure–volume techniques and non-linear least squares analysis to investigate site induced stresses in evergreen trees. Oecologia. 1983;57:380–90.

Baltzer JL, Davies SJ, Bunyavejchewin S, Noor NSM. The role of desiccation tolerance in determining tree species distributions along the Malay-Thai Peninsula. Funct Ecol. 2008;22:221–31.

Lenz TI, Wright IJ, Westoby M. Interrelations among pressure–volume curve traits across species and water availability gradients. Physiol Plant. 2006;127:423–33.

Sanders GJ, Arndt SK. Osmotic adjustment under drought conditions. In: Aroca R, editor. Plant responses to drought stress from morphological to molecular features. Berlin: Springer; 2012. p. 199–229.

Dreyer E, Bousquet F, Ducrey M. Use of pressure volume curves in water relation analysis on woody shoots: influence of rehydration and comparison of four European oak species. Ann For Sci. 1990;47:285–97.

Callister AN, Arndt SK, Adams MA. Comparison of four methods for measuring osmotic potential of tree leaves. Physiol Plant. 2006;127:383–92.

Corcuera L, Camarero JJ, Gil-Pelegrín E. Functional groups in Quercus species derived from the analysis of pressure–volume curves. Trees Struct Funct. 2002;16:465–72.

Parker WC, Colombo SJ. A critical re-examination of pressure–volume analysis of conifer shoots: comparison of three procedures for generating PV curves on shoots of Pinus resinosa Ait. seedlings. J Exp Bot. 1995;46:1701–9.

Parker WC, Pallardy SG. Pressure–volume analysis of leaves of Robinia pseudoacacia L. with the sap expression and free transpiration methods. Can J For Res. 1988;18:1211–3.

Richter H. Water relations of single drying leaves: evaluation with a dewpoint hygrometer. J Exp Bot. 1978;29:277–80.

Martínez EM, Rey BJ, Fandiño M, Cancela JJ. Comparison of two techniques for measuring leaf water potential in Vitis vinifera var. Albariño. J Vitic Enol. 2013;28:29–41.

Campbell EC, Campbell GS, Barlow WK. A dewpoint hygrometer for water potential measurement. Agric Meteorol. 1973;12:113–21.

Nardini A, Gortan E, Ramani M, Salleo S. Heterogeneity of gas exchange rates over the leaf surface in tobacco: an effect of hydraulic architecture? Plant Cell Environ. 2008;31:804–12.

Decagon Devices I. Dewpoint PotentiaMeter. WP4C PotenciaMeter Oper Manual, Version 2 2007;66.

Zhang F-P, Yang Y-J, Yang Q-Y, Zhang W, Brodribb TJ, Hao G-Y, et al. Floral mass per area and water maintenance traits are correlated with floral longevity in Paphiopedilum (Orchidaceae). Front Plant Sci. 2017;08:1–9.

Turner NC. Techniques and experimental approaches for the measurement of plant water status. Plant Soil. 1981;58:339–66.

Allen RG, Pereira LS, Raes D, Smith M. Crop evapotranspiration- guidelines for computing crop water requirements. FAO Irrig Drain Pap. 1998;56:1–15.

Dichio B, Xiloyannis C, Angelopoulos K, Nuzzo V, Bufo SA, Celano G. Drought-induced variations of water relations parameters in Olea europaea. Plant Soil. 2003;381:381–9.

Schulte PJ, Hinckley TM. A comparison of pressure–volume curve data analysis techniques. J Exp Bot. 1985;36:1590–602.

Arndt SK, Irawan A, Sanders GJ. Apoplastic water fraction and rehydration techniques introduce significant errors in measurements of relative water content and osmotic potential in plant leaves. Physiol Plant. 2015;155:355–68.

Bucci SJ, Goldstein G, Meinzer FC, Scholz FG, Franco AC, Bustamante M. Functional convergence in hydraulic architecture and water relations of tropical savanna trees from leaf to whole plant. Tree Physiol. 2004;24:891–9.

Mitchell PJ, O’Grady AP, Tissue DT, White DA, Ottenschlaeger ML, Pinkard EA. Drought response strategies define the relative contributions of hydraulic dysfunction and carbohydrate depletion during tree mortality. New Phytol. 2013;197:862–72.

Khare R. A new approach to derivation of Van’ t Hoff equation for osmotic pressure of a dilute solution. Am Int J Res Sci, Technol, Eng & Math. 2015;11:172–4.

Barrs HD, Kramer PJ. Water potential increase in sliced leaf tissue as a cause of error in vapor phase determinations of water potential. Plant Physiol. 1969;44:959–64.

Authors’ contributions

JMB performed the field work and laboratory analysis, prepared figures, and wrote the manuscript. ADH contributed technical assistance to the experimental design and contributed to the manuscripts revisions. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Glynn Percival, Luke Hailey and Kerry Renshaw for helpful advice and discussions on the manuscript. We also thank Lawren Sack for helpful comments and advice on the manuscript and Kevin Tu for assistance using his P–V curve fitting tool. Additional thanks are due to Bartlett Tree Experts for supporting this research.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

All data is available as supplementary materials.

Consent for publication

Both authors have read this paper and consent to publication.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional file

Additional file 1.

All data, P-V curves raw data, WP4, Vapro, & P-V TLP values.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Banks, J.M., Hirons, A.D. Alternative methods of estimating the water potential at turgor loss point in Acer genotypes. Plant Methods 15, 34 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13007-019-0410-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13007-019-0410-3