Abstract

Background

Salivary gland malignancies are a very heterogeneous group of cancers, with histologically > 20 different subtypes, and prognosis varies greatly. Their etiology is unknown, however, a few small studies show presence of human papillomavirus (HPV) in some subtypes, although the evidence for HPV having a causal role is weak. The aim of this study was to investigate if HPV plays a causal role in the development of different parotid salivary gland tumor subtypes.

Methods

DNA was extracted from 107 parotid salivary gland formalin fixed paraffin embedded tumors and 10 corresponding metastases, and tested for 27 different HPV types using a multiplex bead based assay. HPV DNA positive tumors were stained for p16INK4a overexpression by immunohistochemistry.

Results

One of the 107 malignant parotid salivary gland tumors (0.93%) and its corresponding metastasis on the neck were positive for HPV16 DNA, and both also overexpressed p16INK4a. The HPV positive primary tumor was a squamous cell carcinoma; neither mucoepidermoid nor adenoid cystic tumors were found HPV positive.

Conclusions

In conclusion, HPV DNA analysis in a large number of malignant parotid salivary gland tumors, including 12 different subtypes, did not show any strong indications that tested HPV types have a causal role in the studied salivary gland tumor types.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Salivary gland malignancies are a very heterogeneous group of cancers, where histologically more than 20 different subtypes have been identified and prognosis varies greatly [1]. These tumors are rare, yet affect patients in all age groups and are mainly found in the parotid gland, but can also be found in submandibular, sublingual and accessory parotid glands [2, 3]. In Sweden about 100 new cases of salivary gland cancers are diagnosed each year, accounting for about 8% of head and neck cancers [3], which is similar to 6% of head and neck cancers in the United States [2]. Today the determination of tumor subtype is mainly based on the pathologist’s histological evaluation, and due to the large histological variability in this group of tumors, diagnoses are often determined with uncertainty. As a supportive measure genetic profiling is used in some cases, however, the sensitivity of the tests varies greatly. Moreover, it may often be with great uncertainty the prognostic tumor grade is determined, which is directly correlated to the treatment strategy. The most common treatment strategy is surgery, sometimes followed by postoperative radiation therapy [2, 3].

It has been well established by us and others that human papillomavirus (HPV) plays a causative role in a large proportion of oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas (OPSCC) [4,5,6] and that the mutational burden is lower in HPV positive OPSCC as compared to HPV negative OPSCC [7]. It is also well established that HPV can be valuable as a prognostic tool, since patients with HPV positive OPSCC have a much better clinical outcome compared to patients with HPV negative OPSCC [8]. However, whether HPV has a causal effect in salivary gland carcinomas is not as certain. A recent study indicated that there are major differences in mutation frequencies between different salivary gland tumor subtypes, where none or few mutations were found in mucoepidermoid, adenoid cystic and acinic cell subtypes [9], suggesting that other factors such as e.g. a viral infection may be the causative factor. There are a handful small studies that have shown an association between HPV infection and certain salivary gland malignancies, however, reported HPV prevalence varied to a great extent, as summarized in Additional file 1: Table S1 [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. Moreover, these studies included only a small sample size, and most studies only included one or few specific subtypes of salivary gland tumors with very few samples in each subgroup, thus missing proper control groups. In this study we investigated the occurrence of HPV (defined as being HPV DNA positive and overexpressing p16INK4a) in, to our knowledge, the largest cohort of parotid salivary gland tumors, including 12 different subtypes, in patients diagnosed between 2000-2009 in the counties of Stockholm and Gotland.

Methods

Patients and tumor samples

Between 2000-2009, 145 patients in the counties of Stockholm and Gotland were identified and diagnosed with the following types of malignant parotid salivary gland tumors: acinic cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma not otherwise specified (NOS), adenoid cystic carcinoma, basal cell adenocarcinoma, epithelial- myoepithelial carcinoma, mucoepidermoid carcinoma, myoepithelial carcinoma, oncocytic carcinoma, poorly differentiated carcinoma, salivary duct carcinoma, secretory carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma (ICD-10: C07.9). From these, haematoxylin and eosin stained tumor sections were histologically evaluated to confirm presence of malignant cells and diagnosis. In total 117 biopsies (including 10 corresponding metastases) from 107 unique patients had sufficient tumor material for inclusion in this study and were collected as formalin fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE) tumors from the Clinical Pathology Department at Karolinska University Hospital. Sections from the FFPE tumors with, when possible, > 70% tumor cell area were taken for DNA extraction and immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining.

DNA extraction and detection of HPV

DNA was extracted from 10 μm FFPE tumor tissue sections using the QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following the manufacturer’s suggested protocol. In short, the FFPE sections were dissolved in Xylene followed by rehydration in absolute ethanol. After protein degradation the samples were purified in several steps using spin columns, thereafter the purified DNA was stored at − 20 °C. For each tumor sample a blank paraffin section was included as a negative control in order to detect possible cross-contamination between samples. Presence of HPV DNA was detected, following a 40 cycle PCR amplification using the QIAGEN multiplex PCR kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) together with broad-spectrum GP5+/6+ primers (Cybergene, Stockholm, Sweden) [18]. PCR products were then hybridized to specific probes for 27 different HPV types (HPV 6, 11, 16, 18, 26, 30, 31, 33, 35, 39, 42, 43, 44, 45, 51, 52, 53, 56, 58, 59, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 73 and 82) and evaluated on a Magpix instrument (Luminex Corporation, Austin, USA) for the different HPV types as previously described [19, 20]. β-globin was included as a positive control for presence of DNA as described previously [21]. In addition, negative controls with distilled water and positive controls with SiHa cells corresponding to 5, 50 and 500 HPV genomes were also included and treated per protocol.

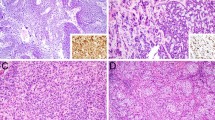

p16INK4a overexpression

The tumor that tested positive for HPV was also evaluated for p16INK4a tumor suppressor protein (p16) overexpression. p16 overexpression was determined by IHC using the mouse monoclonal antibody CINtec® p16 Histology (clone E6H4, Ventana, Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland), as previously described [21]. The sections were evaluated by a pathologist, where a ≥ 70% stained tumor was considered as positive for p16 overexpression, and < 70% as negative.

Statistical analysis

Fisher’s exact test was used to compare HPV numbers per sub-group of salivary gland tumors.

Results

In total 117 tumor samples, including 10 corresponding metastases, from 12 different salivary gland tumor types, were analyzed for presence of HPV DNA (Table 1). All samples were positive for the β-globin gene used as a positive control, indicating successful DNA purification. One out of the 107 (0.93%) tested malignant salivary gland primary tumors was positive for HPV16, which was 1/7 salivary gland squamous cell carcinomas included in this study. This tumor also showed p16 overexpression. No significant overrepresentation of HPV DNA was observed in squamous cell carcinomas as compared to the other subgroups (p = 0.06, Table 1). Moreover, the HPV16 and p16 positive tumor had a corresponding metastasis located on the neck, which also was positive for HPV16 and p16.

The patient with an HPV positive tumor was a 78-year old male patient with severe co-morbidities and no history of other tumors. Tumor origin was evaluated clinically and radiologically with no evidences of other origins than the parotid gland; the oropharynx was however not assessed histologically. Since the patient died some months after diagnosis, the follow-up was limited.

Discussion

In this study, 107 malignant salivary gland tumors, including 12 different subtypes, with the addition of 10 corresponding metastases were tested for the presence of 27 different HPV types (including all known high risk HPV types) using a multiplex bead based assay. One of the 107 malignant salivary gland tumors and its corresponding metastasis on the neck were positive for HPV16 DNA, and both also overexpressed p16 and therefore could be defined as being HPV positive. All other subtypes tested were HPV DNA negative. In total, only one of seven squamous cell carcinoma salivary gland tumors was HPV positive and due to the small sample size of squamous cell salivary gland tumors it was not possible to draw any reliable conclusion to whether HPV was involved in the development of this tumor type. Furthermore, all other subgroups lacked high risk HPV DNA and did not express presence of any of the other tested HPV types, suggesting that HPV does not play a major role as a causative agent in these subgroups. The latter was shown in a more limited study by Skalova et al. [13].

Nonetheless, HPV positive head and neck cancers often present with an HPV positive neck metastasis, and it has been shown that HPV positive cancer of unknown primary of the head and neck region often originate from an HPV positive OPSCC [22, 23]. Hence there is also a possibility that the HPV16 positive squamous cell salivary gland carcinoma found in this study was instead a primary tumor, or a cancer of unknown primary originating from an undetected OPSCC. This would further support that HPV does not play a major role for the development of salivary gland tumors. However, the clinical evaluation in this case did not support such an assumption.

There are some limitations to this study. Firstly, salivary gland tumors are a rare and heterogeneous group of tumors including more than 20 different subtypes, making it difficult to gather representable amounts of material for this type of analysis. Furthermore, although, to our knowledge, the presence of HPV was analyzed in the largest cohort published so far, the number of samples per subgroup was still limited, which makes it difficult to draw any clear conclusions. Secondly, the presence of p16 overexpression in samples was only tested on the one sample, and its corresponding metastasis, that both had tested positive for HPV DNA. Nevertheless, previous studies have shown p16 overexpression in malignant salivary gland tumor cohorts, still lacking or having a low correlation to presence of HPV [11, 13]. These findings may also be indicative of HPV not playing the cancer-driving role and that p16 in these tumors is a bad surrogate marker for an active HPV infection. Lastly, the HPV16 positive tumor found in this study was one out of seven squamous cell carcinomas, which is a very rare type of salivary gland tumor. Here, no significant overrepresentation of HPV was observed in squamous cell carcinomas as compared to the other sybtypes. However, the numbers of squamous cell carcinomas was restricted and the results should be interpreted with caution. With a larger cohort of squamous cell salivary gland carcinomas, perhaps more conclusive results could be drawn to whether HPV is a causative agent in the development of these tumors or not.

Conclusions

In conclusion, HPV DNA analysis in a large number of malignant salivary gland tumors, including 12 different subtypes, did not show any strong indications that tested HPV types have a causal role in the studied salivary gland tumor types.

Abbreviations

- FFPE:

-

Formalin fixed paraffin embedded

- HPV:

-

Human papillomavirus

- IHC:

-

Immunohistochemistry

- NOS:

-

Not otherwise specified

- OPSCC:

-

Oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma

- p16:

-

p16INK4a tumor suppressor protein

References

Gillespie MB, Albergotti WG, Eisele DW. Recurrent salivary gland cancer. Curr Treat Options in Oncol. 2012;13:58–70.

Barnes L, Eveson JW, Peter Reichart DS. WHO classification of Tumours. Pathol Genet Head Neck Tumours. 2005;9:209–81.

Cancercentrum R. Nationellt vårdprogram Huvud- och halscancer. 2015. http://www.cancercentrum.se/globalassets/cancerdiagnoser/huvud-och-hals/vardprogram/natvp_huvud-hals_v1.0_150825_final.pdf.

Dahlstrand HM, Dalianis T. Presence and influence of human papillomaviruses (HPV) in tonsillar cancer. Adv Cancer Res. 2005;93:59–89.

International Agency for Research on Cancer. IARC monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans, vol. 90. Lyon, France: Human papillomaviruses; 2007.

Gillison ML, Koch WM, Capone RB, Spafford M, Westra WH, Wu L, et al. Evidence for a causal association between human papillomavirus and a subset of head and neck cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:709–20. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/92.9.709.

Bersani C, Sivars L, Haeggblom L, DiLorenzo S, Mints M, Ährlund-Richter A, et al. Targeted sequencing of tonsillar and base of tongue cancer and human papillomavirus positive unknown primary of the head and neck reveals prognostic effects of mutated FGFR3. Oncotarget. 2017;8:35339–50. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.15240.

Lindquist D, Romanitan M, Hammarstedt L, Näsman A, Dahlstrand H, Lindholm J, et al. Human papillomavirus is a favourable prognostic factor in tonsillar cancer and its oncogenic role is supported by the expression of E6 and E7. Mol Oncol. 2007;1:350–5.

Grünewald I, Vollbrecht C, Meinrath J, Meyer MF, Heukamp LC, Drebber U, et al. Targeted next generation sequencing of parotid gland cancer uncovers genetic heterogeneity. Oncotarget. 2015;6:18224–37. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.4015.

Isayeva T, Li Y, Maswahu D, Brandwein-Gensler M. Human papillomavirus in non-oropharyngeal head and neck cancers: a systematic literature review. Head Neck Pathol. 2012;6(SUPPL. 1):104–20.

Boland JM, McPhail ED, García JJ, Lewis JE, Schembri-Wismayer DJ. Detection of human papilloma virus and p16 expression in high-grade adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck. Mod Pathol. 2012;25:529–36. https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2011.186.

Vageli D, Sourvinos G, Ioannou M, Koukoulis GK, Spandidos DA. High-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) in parotid lesions. Int J Biol Markers. 2007;22:239–44.

Skalova A, Kaspirkova J, Andrle P, Hosticka L, Vanecek T. Human papillomaviruses are not involved in the etiopathogenesis of salivary gland tumors. Ces Patol. 2013;49:72–5.

Hafed L, Farag H, Shaker O, El-Rouby D. Is human papilloma virus associated with salivary gland neoplasms? An in situ-hybridization study. Arch Oral Biol. 2012;57:1194–9.

Lin FC, Chen PL, Tsao TY, Li CR, Jeng KC, Tsai SC. Prevalence of human papillomavirus and Epstein-Barr virus in salivary gland diseases. J Int Med Res. 2014;42:1093–101.

Qian X, Kaufmann AM, Chen C, Tzamalis G, Hofmann VM, Keilholz U, et al. Prevalence and associated survival of high-risk HPVrelated adenoid cystic carcinoma of the salivary glands. Int J Oncol. 2016;49:803–11. https://doi.org/10.3892/ijo.2016.3563.

Xu B, Wang L, Borsu L, Ghossein R, Katabi N, Ganly I, et al. A proportion of primary squamous cell carcinomas of the parotid gland harbour high-risk human papillomavirus. Histopathology. 2016;69:921–9.

Schmitt M, Dondog B, Waterboer T, Pawlita M. Homogeneous amplification of genital human alpha papillomaviruses by PCR using novel broad-spectrum GP5+ and GP6+ primers. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:1050–9.

Nordfors C, Grün N, Haeggblom L, Tertipis N, Sivars L, Mattebo M, et al. Oral human papillomavirus prevalence in high school students of one municipality in Sweden. Scand J Infect Dis. 2013;45:878–81. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.3109/00365548.2013.821626.

Du J, Nordfors C, Ahrlund-Richter A, Sobkowiak M, Romanitan M, Näsman A, et al. Prevalence of oral human papillomavirus infection among youth, Sweden. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18:1468–71. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1809.111731.

Dalianis T, Grün N, Koch J, Vlastos A, Tertipis N, Nordfors C, et al. Human papillomavirus DNA and p16(INK4a) expression in hypopharyngeal cancer and in relation to clinical outcome, in Stockholm, Sweden. Oral Oncol. 2015;51:857–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oraloncology.2015.06.002.

Sivars L, Näsman A, Tertipis N, Vlastos A, Ramqvist T, Dalianis T, et al. Human papillomavirus and p53 expression in cancer of unknown primary in the head and neck region in relation to clinical outcome. Cancer Med. 2014;3:376–84.

Begum S, Gillison ML, Ansari-Lari MA, Shah K, Westra WH. Detection of human papillomavirus in cervical lymph nodes: a highly effective strategy for localizing site of tumor origin. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:6469–75.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank professor Tina Dalianis for providing tumour material.

Funding

This work was supported by Stiftelsen Clas Groschinskys minnesfond, Stiftelsen Tornspiran, Stiftelsen Dagmar Ferbs minnesfond, Svenska läkaresällskapet (SLS), Stiftelsen Sigurd och Elsa Goljes Minne, Magnus Bergvalls stiftelse, Eva och Oscar Ahréns stiftelse, Tore Nilssons Stiftelse för medicinsk forskning, Svenska Sällskapet för Medicinsk Forskning (SSMF), the Stockholm County Council (SLL) and Karolinska Institutet. RGU was funded by the University of Medicine and Pharmacy Grigore T Popa Iasi, based on contract no. 30336 / 28.12.2017. The funding bodies had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation of data, or in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Please contact author for data requests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CG, LHN and AN formulated the research question and came up with the study design. Sample selection and collection was done by AN and LH. RGU, LM and TA performed the DNA extractions and PCR reactions. LH, RGU, LM and TA performed the HPV typing via Luminex technologies as well as the data analysis. LH and AN summarized and interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript which was revised and approved by all co-authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Patient material was obtained according to ethical permission 2005/431–31/4, granted by the Ethics Committee at Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden. Informed consent was given by all participants for biobanking of patient material and use for research.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Table S1. Summary of studies on salivary gland tumors in relation to HPV infection as referred to in the background section. (DOCX 33 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Haeggblom, L., Ursu, R.G., Mirzaie, L. et al. No evidence for human papillomavirus having a causal role in salivary gland tumors. Diagn Pathol 13, 44 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13000-018-0721-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13000-018-0721-0