Abstract

Background

Pelvic girdle pain is a common problem during pregnancy and postpartum with significant personal and societal impact and costs. Studies examining the effectiveness of interventions for pelvic girdle pain measure different outcomes, making it difficult to pool data in meta-analysis in a meaningful and interpretable way to increase the certainty of effect measures. A consensus-based core outcome set for pelvic girdle pain can address this issue. As a first step in developing a core outcome set, it is essential to systematically examine the outcomes measured in existing studies.

Objective

The objective of this systematic review was to identify, examine and compare what outcomes are measured and reported, and how outcomes are measured, in intervention studies and systematic reviews of interventions for pelvic girdle pain and for lumbopelvic pain (which includes pelvic girdle pain).

Methods

We searched PubMed, Cochrane Library, PEDro and Embase from inception to the 11th May 2018. Two reviewers independently selected studies by title/abstract and by full text screening. Disagreement was resolved through discussion. Outcomes reported and their outcome measurement instruments were extracted and recorded by two reviewers independently. We assessed the quality of reporting with two independent reviewers. The outcomes were grouped into core domains using the OMERACT filter 2.0 framework.

Results

A total of 107 studies were included, including 33 studies on pelvic girdle pain and 74 studies on lumbopelvic pain. Forty-six outcomes were reported across all studies, with the highest amount (26/46) in the ‘life impact’ domain. ‘Pain’ was the most commonly reported outcome in both pelvic girdle pain and lumbopelvic pain studies. Studies used different instruments to measure the same outcomes, particularly for the outcomes pain, function, disability and quality of life.

Conclusions

A wide variety of outcomes and outcome measurements are used in studies on pelvic girdle pain and lumbopelvic pain. The findings of this review will be included in a Delphi survey to reach consensus on a pelvic girdle pain - core outcome set. This core outcome set will allow for more effective comparison between future studies on pelvic girdle pain, allowing for more effective translation of findings to clinical practice.

Resumen en Español

Introducción

El dolor de la cintura pélvica es un problema común durante el embarazo y el posparto con un impacto personal y social significativo. Los estudios que examinan la efectividad de intervenciones para el dolor de la cintura pélvica miden diferentes resultados, lo que dificulta el agrupamiento de los datos en un metanálisis para aumentar la certeza de las medidas del efecto. Un conjunto de resultados principales basado en un consenso puede abordar este problema. Primero, para desarrollar un conjunto de resultados principales, es esencial examinar sistemáticamente los resultados utilizados en los estudios existentes.

Objetivo

El objetivo de esta revisión sistemática fue identificar, examinar y comparar qué resultados se miden y reportan, y cómo se los miden, en estudios de intervención y revisiones sistemáticas de intervenciones para el dolor de la cintura pélvica y para el dolor lumbopélvico.

Método

Se realizaron búsquedas en PubMed, Cochrane Library, PEDro y Embase desde el inicio hasta el 11 mayo 2018. Dos revisores seleccionaron independientemente los estudios por título/resumen y texto completo. El desacuerdo se resolvió por discusión. Los resultados reportados y sus instrumentos de medición fueron extraídos por dos revisores independiente. Se evaluó la calidad de informe con dos revisores independientes. Los resultados se agruparon en dominios principales utilizando el filtro OMERACT 2.0.

Resultados

Se incluyeron 107 artículos: 33 artículos sobre el dolor de la cintura pélvica y 74 artículos sobre el dolor lumbopélvico. Se informaron 46 resultados, principalmente (26/46) en el dominio “Impacto en la vida”. “El Dolor” fue el resultado más frecuente. Los estudios utilizaron diferentes instrumentos para medir los mismos resultados, particularmente para los resultados dolor, función, discapacidad y calidad de vida.

Conclusiones

Se utiliza una amplia variedad de resultados y mediciones de resultados en estudios sobre el dolor de la cintura pélvica y el dolor lumbopélvico. Los resultados de esta revisión se incluirán en una encuesta Delphi, obtener para llegar a un consenso sobre un conjunto de resultados principales. Este conjunto de resultados principales permitirá una comparación más efectiva entre estudios sobre el dolor de la cintura pélvica, lo que permitirá un análisis más efectivo en la práctica clínica.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Pelvic Girdle Pain (PGP) has been defined as “pain between the posterior iliac crest and the gluteal fold, particularly in the vicinity of the sacroiliac joints, and pain may radiate to the posterior thigh and can also occur in conjunction with/or separately in the symphysis” [1] (pp797). In the past, it has sometimes been considered a subgroup of low back pain (LBP); however, PGP includes also pain at the pubic symphysis and is therefore considered a different entity. The term lumbopelvic pain (LPP) is a broader term that has been used to describe LBP and/or PGP without differentiation between the two groups [2].

Pelvic Girdle Pain is a common complaint during pregnancy, affecting 23 to 65% of women depending on how it is measured and defined [3, 4]. Although many women recover after the birth, 17% have continuing symptoms 3 months postpartum [2] and 8.5% have not recovered 2 years postpartum [5]. In Sweden, in a cohort of 371 women with PGP, 10% of women still had symptoms 11 years after the birth [6]. In another Swedish cohort, 40.3% had long term pain in the low back or pelvic girdle area 12 years postpartum [7]. Additionally, PGP is one of the leading causes of sick leave during pregnancy [7,8,10], resulting in large economic costs to families and society.

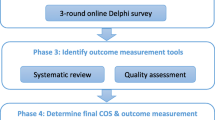

Studies examining the effectiveness of interventions for PGP measure different outcomes, making it difficult and sometimes impossible to pool data in meta-analysis to increase the certainty of effect measures [11, 12]. To address this issue, an international consensus-based Core Outcome Set (COS) for PGP is being developed (registration: http://www.comet-initiative.org/studies/details/958) [13]. The systematic review presented here forms the first key part of the PGP-COS (Pelvic Girdle Pain – Core Outcome Set) study and provides a structured overview of the outcomes and outcome measurements that are used across PGP as well as LPP (since this includes PGP) intervention studies and systematic reviews. It will feed into the larger PGP-COS study by providing a preliminary list of outcomes that will be included into an online Delphi survey and face-to-face consensus meeting to identify a final COS for PGP.

The objective of this systematic review was to identify and examine what outcomes are measured and reported, and how outcomes are measured, in intervention studies and systematic reviews of interventions for PGP.

Methods

The protocol for this systematic review was published as part of the PGP-COS study protocol [13]. Criteria for considering papers for inclusion in the systematic review are outlined in Table 1. A second objective (To compare outcomes measured in intervention studies and systematic reviews on PGP to outcomes measured in studies on LPP) was added post hoc, since many studies that we identified in preliminary searches did not differentiate between LBP or PGP, and it was considered important to compare outcomes measured in these studies since LPP includes PGP. We analysed and have presented the results by the subgroups PGP and LPP.

Search methods & study selection

The following databases were searched on the 11th May 2018 (from inception): PubMed, the Cochrane Library, PEDro and Embase. Details of search terms used for each database can be found in Additional file 1. No language or time filters were applied. We screened reference lists of included studies for further relevant studies. Citations were exported to Endnote and duplicates were removed. Two review authors (FW, MO) reviewed each citation independently against the inclusion criteria in two stages: (a) title and abstract screening and (b) full text screening, using Covidence software [14]. Disagreement was resolved through discussion.

Data collection and synthesis

All outcomes (and their verbatim definitions) examined in the included studies were extracted by two reviewers (FW, MO) independently and their corresponding outcome measurement instruments/methods, where reported, were also recorded. The quality of outcome reporting was assessed using the six questions proposed by Harmen et al. [15] and this was conducted by two independent reviewers (FW, MO). The outcomes were then grouped into core outcome domains using the OMERACT (Outcome measures in rheumatology) filter 2.0 framework: (a) life impact; (b) resource use/economic impact; (c) pathophysiological manifestations and (d) death [16]. This framework aims to provide a structure for measuring outcomes and developing core outcome sets. Within the OMERACT framework ‘adverse events’ should also be flagged alongside the core domains. We therefore grouped adverse events into a separate domain [16]. The findings are synthesised and reported by these core domains, for PGP and LPP separately, for comparison. We have reported this systematic review according to the PRISMA guideline [17].

Results

Screening and selection of included papers

A total of 7092 studies were identified from the initial search after removal of duplicates. We excluded 6842 studies during title and abstract screening, and the full texts of 250 articles were reviewed. A total of 145 studies were excluded at full text selection. Reasons for exclusion were: duplicates (n = 30), the wrong study design (n = 67), published in a language other than English (n = 7), examining LBP only (n = 30), or the wrong study population (n = 11). A further two studies were identified for inclusion from screening reference lists of included studies, with a total of 107 studies being included in the analysis. Figure 1 provides a flow diagram detailing the results of the search and selection process.

Characteristics of included studies

Of the 107 studies included in the review, 31 were systematic reviews, 61 were Randomised Controlled Trials (RCTs) (including one follow up study [18] of another included study [19]), 11 were non-controlled intervention studies, two studies were non-randomised controlled studies [20, 21] and one study identified itself as a quasi-randomised design because no blinding of participates took place [22]. A total of 33 studies on PGP and 74 studies on LPP were included. Studies were published between the year 1991 and 2018, with 54% of studies published in the last 5 years. Studies were undertaken in a variety of geographical locations, across Europe, North and South America, Australia, New Zealand, Asia and Africa, with the highest percentage in Europe (66%), particularly in Sweden and Norway (30% of all included studies). Of the studies that focused on PGP, 24 studies (72.7%) included a physical examination as a requirement for the diagnosis of PGP. In comparison, only 18 (24.3%) of the studies focusing on LPP included a physical examination as a requirement for a diagnosis of LPP. Additional details of the characteristics of included studies can be found in Additional file 2.

An overview of the quality of reporting of the included studies [15] is presented in Tables 2 and 3, with higher quality reporting indicated by a yes vote, where applicable. All PGP studies (100%) and most LPP studies (94%) clearly reported and defined the primary outcome(s). About two thirds of studies did not differentiate between primary and secondary outcomes, making questions three and four not applicable. For transparency, the full quality of reporting assessment of each study determined by the six questions outlined by Harmen et al. [15] can be found in Additional file 3.

Outcomes and outcome measurements

A total of 46 outcomes were identified and categorised into core domains using the OMERACT filter 2.0 framework: ‘life impact’, ‘resource use/economic impact’, ‘pathophysiological manifestations’ and ‘death’. No outcomes were identified in the core domain ‘death’, but ‘adverse events’ outcomes were identified. Outcomes and their corresponding outcome measurements are presented separately for studies that focused on PGP or focused on LPP in the Tables 4, 5, 6 and 7. Of the 46 outcomes identified, 26 were in the life impact core domain (Table 4), five were in the resource-use/economic impact domain (Table 5), 11 were in the pathophysiological domain (Table 6), and four outcomes were classified in the adverse events domain (Table 7).

The differences in the number of outcomes reported in studies on PGP and studies on LPP by core domain are outlined in the Table 8. Notable, psychological outcomes and economic outcomes were more commonly measured in LPP studies compared to PGP studies. A further comparison of the different outcomes reported in each domain between PGP and LPP studies is outlined in Additional file 4.

Discussion

A large number of primary intervention studies (n = 76) and systematic reviews (n = 31) were identified. A total of 46 outcomes were measured across all studies. The majority of outcomes related to the ‘life impact’ core domain of the OMERACT framework. This would be expected considering the nature and main symptoms of PGP and LPP. Within the life impact core domain, pain intensity was the most commonly reported outcome in both PGP and LPP studies, followed by the outcomes function and disability. Fifteen (20%) studies on LPP included psychological outcomes versus only three (9%) PGP studies. This is likely because LPP includes LBP, which has had a strong psychosocial focus within the literature the past few decades, including on aspects such as fear avoidance and catastrophising. It might be that PGP is often perceived as a transient condition related to pregnancy and researchers therefore assess fewer psychosocial factors that are involved in developing chronicity. However, not all women recover and PGP can persist postpartum [2, 5-7, 118]. Moreover, PGP has been associated with psychological factors including emotional distress [119], depression [118, 120] and anxiety [118]. Only 14 studies/reviews (13%) examined any adverse events. This is contrary to current recommendations to always assess adverse events for any intervention study or systematic review [121, 122].

A range of outcome measurements were used across studies to measure certain outcomes. For example, pain intensity alone was measured using 10 different outcome measurement instruments, and function was examined using 13 different tools across the studies. This emphasises not only the need for a COS but also for consensus on how to measure the identified COS. This systematic review will contribute to a list of initial outcomes to be included in a multistakeholder, international Delphi survey to reach consensus on a PGP-COS. Subsequently, the next part of the PGP-COS study will determine ‘how’ best to measure the developed COS [13].

This systematic review also showed that the included intervention studies/reviews often use different terminology to describe the same outcomes. For example, when examining the measurement tools for the outcomes ‘function’ and ‘disability’, the same tools are frequently used. While some studies use the term ‘function’ and others ‘disability’, most studies do not provide a clear definition of the terms. Another example of where there is clearly inconsistency in terminology and a lack of definitions in original manuscripts is for the outcomes ‘quality of life’ and ‘health status’. Again, the same measurement instruments tend to be used and terms seem to be used interchangeably across different studies. This observed inconsistency strengthens the rationale for the development of an agreed PGP-COS.

Chiarotto et al. [123] published a COS for non-specific LBP in 2015 and, while there was some overlap in findings, the list of outcomes they identified from the LBP literature differed significantly from our findings of the outcomes measured in the PGP/LPP literature. They identified the following outcomes in LBP studies that were not identified in our review of PGP/LPP studies: death, cognitive functioning, social functioning, sexual functioning, satisfaction with social role and activities, pain quality, independence (Life impact); informal care, societal services, legal services (Resource-use/ economic impact); muscle tone, proprioception, spinal control, and physical endurance (Pathophysiological manifestations). Outcomes that we identified in this review of PGP/LPP studies but that were not identified in the review of the outcomes measured in the LBP literature [123] were: Self-efficacy, confidence, patient expectations of treatment (Life impact); and anthropometric measures (weight/height), pregnancy and maternal outcomes, surgical outcomes (Physiological manifestations). Some of the observed differences could be put down to differences between PGP and LBP. However, differences in outcomes seem largely arbitrary instead of relating to the distinguishing features of PGP and LBP. Similarly, when comparing studies examining PGP only with studies examining LPP in this systematic review, the reason for the observed discrepancies in the outcomes chosen by studies’ authors are mostly unclear. This supports using the outcomes identified in this review only as an initial list for the consensus process to develop a PGP COS, allowing for other outcomes to be added by all stakeholders including patients, clinicians, researchers, service providers and policy makers.

Conclusions

Studies and systematic reviews examining the effectiveness of interventions for PGP and LPP assess a range of outcomes, predominantly pain intensity and disability/function, and use a large variety of outcome measurement instruments. Few studies examine adverse events and economic outcomes. Not only do different studies often measure different outcomes, authors also rarely define outcomes and terminology for outcomes varies, making comparison of study findings very difficult.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- 6MWT:

-

6 min walk test

- ADL:

-

Activities of daily living

- ASIS:

-

Anterior superior iliac spine

- BDQ:

-

Bournemouth disability questionnaire

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- BPFS:

-

Brief psychiatric rating scale

- COS:

-

Core outcome set

- CT scan:

-

Computerised tomography scan

- DRI:

-

Disability rating index

- EQ-VAS:

-

EurQoL visual analogue scales

- EurQoL – EQ-5:

-

EurQoL 5 dimensions

- HSCL:

-

Hopkins symptom checklist

- ICIQ:

-

International consultation on incontinence questionnaire

- KG:

-

Kilogram

- LBP:

-

Low back pain

- LPP:

-

Lumbopelvic pain

- NHP:

-

Nottingham health profile

- NRS:

-

Numeric rating scale

- ODI:

-

Oswestry disability index

- OMERACT:

-

Outcome measures in rheumatology

- PFM:

-

Pelvic floor muscles

- PGP:

-

Pelvic girdle pain

- PGQ:

-

Pelvic girle questionnaire

- PMI:

-

Pregnancy mobility index

- POM-VAS:

-

Pain-O-meter visual analogue scale

- PPAQ:

-

Pregnancy Physical Activity Questionnaire

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses

- PSFS:

-

Patient-specific functional scale

- PSIS:

-

Posterior Superior Iliac Spine

- QBPDS:

-

Quebec back pain disability scale

- QoL:

-

Quality of life

- RCT:

-

Randomised controlled trial

- RMDQ:

-

Roland Morris disability questionnaire

- SF-12:

-

Short form 12

- SF-36:

-

Short form 36

- SIJ:

-

Sacroiliac joint

- SWLS:

-

Satisfaction with life scale

- TUG:

-

Timed up and go test

- VAS:

-

Visual analogue scale

References

Vleeming A, Albert HB, Ostgaard HC, Sturesson B, Stuge B. European guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pelvic girdle pain. Eur Spine J. 2008;17(6):794–819.

Gutke A, Lundberg M, Ostgaard HC, Oberg B. Impact of postpartum lumbopelvic pain on disability, pain intensity, health-related quality of life, activity level, kinesiophobia, and depressive symptoms. Eur Spine J. 2011;20(3):440–8.

Kovacs FM, Garcia E, Royuela A, Gonzalez L, Abraira V. Prevalence and factors associated with low back pain and pelvic girdle pain during pregnancy: a multicenter study conducted in the Spanish National Health Service. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2012;37(17):1516–33.

Albert HB, Godskesen M, Westergaard JG. Incidence of four syndromes of pregnancy-related pelvic joint pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002;27(24):2831–4.

Albert H, Godskesen M, Westergaard J. Prognosis in four syndromes of pregnancy-related pelvic pain. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2001;80(6):505–10.

Elden H, Gutke A, Fagevik-Olsen M, Kjellby-Wendt G, Ostgaard H. Predictors of long-term pelvic girdle pain and its consequences on health and function after pregnancy with a classified PGP: a longitudinal follow-up study. Pain practice. 2016;16:76.

Bergstrom C, Persson M, Nergard KA, Mogren I. Prevalence and predictors of persistent pelvic girdle pain 12 years postpartum. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2017;18(1):399.

Malmqvist S, Kjaermann I, Andersen K, Okland I, Larsen JP, Bronnick K. The association between pelvic girdle pain and sick leave during pregnancy; a retrospective study of a Norwegian population. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:237.

Dorheim SK, Bjorvatn B, Eberhard-Gran M. Sick leave during pregnancy: a longitudinal study of rates and risk factors in a Norwegian population. BJOG. 2013;120(5):521–30.

Mogren I. Previous physical activity decreases the risk of low back pain and pelvic pain during pregnancy. Scand J Public Health. 2005;33(4):300–6.

Gutke A, Betten C, Degerskar K, Pousette S, Olsen MF. Treatments for pregnancy-related lumbopelvic pain: a systematic review of physiotherapy modalities. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2015;94(11):1156–67.

Liddle SD, Pennick V. Interventions for preventing and treating low-back and pelvic pain during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015(9):Cd001139. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001139.pub4.

Wuytack F, Gutke A, Stuge B, Morkved S, Olsson C, Robinson HS, et al. Protocol for the development of a core outcome set for pelvic girdle pain, including methods for measuring the outcomes: the PGP-COS study. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):158.

Veritas Health Innovation. Covidence systematic review software. Melbourne, Australia.

Harmen NL, Bruce IA, Callery P, Tierney S, Sharif MO, O'Brien K, et al. MOMENT – Management of otitis media with effusion in cleft palate: protocol for a systematic review of the literature and identification of a core outcome set using a Delphi survey. Trials. 2013;14:70.

Boers M, Kirwan JR, Wells G, Beaton D, Gossec L, d'Agostino M-A, et al. Developing Core outcome measurement sets for clinical trials: OMERACT filter 2.0. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(7):745–53.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

Bastiaenen CHG, de Bie RA, Vlaeyen JWS, Goossens MEJB, Leffers P, Wolters PMJC, et al. Long-term effectiveness and costs of a brief self-management intervention in women with pregnancy-related low back pain after delivery. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2008;8:19.

Bastiaenen C, Bie R, Wolters P, Vlaeyen J, Leffers P, Stelma F, et al. Effectiveness of a tailor-made intervention for pregnancy-related pelvic girdle and/or low back pain after delivery: short-term results of a randomized clinical trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2006;7:19.

Bhandiwad A, Vaisravanath S, Sujatha MS. Role of short term exercise intervention in pelvic girdle pain in pregnancy. Physiotherapy (United Kingdom). 2015;101:eS147–eS8.

Shim MJ, Lee YS, Oh HE, Kim JS. Effects of a back-pain-reducing program during pregnancy for Korean women: a non-equivalent control-group pretest-posttest study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2007;44(1):19–28.

Guerreiro Da Silva JB, Nakamura MU, Cordeiro JA, Kulay L Jr. Acupuncture for low back pain in pregnancy - a prospective, quasi-randomised, controlled study. Acupunct Med. 2004;22(2):60–7.

Elden H, Fagevik-Olsen M, Ostgaard H, Stener-Victorin E, Hagberg H. Acupuncture as an adjunct to standard treatment for pelvic girdle pain in pregnant women: randomised double-blinded controlled trial comparing acupuncture with non-penetrating sham acupuncture. BJOG 2008;115(13):1655–1668.

Elden H, Östgaard H, Glantz A, Marciniak P, Linnér A, Olsén M. Effects of craniosacral therapy as adjunct to standard treatment for pelvic girdle pain in pregnant women: a multicenter, single blind, randomized controlled trial. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2013;92(7):775–82.

Ladfors L, Elden H, Olsen M, Ostgaard H. Effects of acupuncture and specific stabilizing exercises among women with pregnancy-related pelvic pain: a randomised single blind controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191(6 Suppl 1):S77.

Melkersson C, Nasic S, Starzmann K, Bengtsson Bostrom K. Effect of foot manipulation on pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain: a feasibility study. J Chiropr Med. 2017;16(3):211–9.

Bertuit J, Van Lint CE, Rooze M, Feipel V. Pregnancy and pelvic girdle pain: analysis of pelvic belt on pain. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27(1–2):e129–e37.

Haugland K, Rasmussen S, Daltveit A. Group intervention for women with pelvic girdle pain in pregnancy. A randomized controlled trial. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2006;85(11):1320–6.

Mens J, Snijders C, Stam H. Diagonal trunk muscle exercises in peripartum pelvic pain: a randomized clinical trial. Phys Ther. 2000;80(12):1164–73.

Torstensson T, Lindgren A, Kristiansson P. Corticosteroid injection treatment to the ischiadic spine reduced pain in women with long-lasting sacral low back pain with onset during pregnancy: a randomized, double blind, controlled trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34(21):2254–8.

Elden H, Hagberg H, Olsen M, Ladfors L, Ostgaard H. Regression of pelvic girdle pain after delivery: follow-up of a randomised single blind controlled trial with different treatment modalities. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2008;87(2):201–8.

Elden H, Ladfors L, Olsen M, Ostgaard H, Hagberg H. Effects of acupuncture and stabilising exercises as adjunct to standard treatment in pregnant women with pelvic girdle pain: randomised single blind controlled trial. BMJ (clinical research ed). 2005;330(7494):761.

Torstensson T, Lindgren A, Kristiansson P. Improved function in women with persistent pregnancy-related pelvic pain after a single corticosteroid injection to the ischiadic spine: a randomized double-blind controlled trial. Physiother Theory Pract. 2013;29(5):371–8.

Almousa S, Lamprianidou H, Kitsoulis G. The effectiveness of stabilizing exercises in pelvic girdle pain during preg nancy and after delivery: a systematic review. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2015;26(1):S52–S3.

Barfoot C, Tudor R, D'Almeida I, Joice D, Staples S, Smith R, et al. A pilot randomised trial of 4 physiotherapy interventions for pregnancy related pelvic girdle pain. Physiotherapy (United Kingdom). 2015;101:eS111.

Flack N, Hay-Smith E, Stringer M, Gray A, Woodley S. Adherence, tolerance and effectiveness of two different pelvic support belts as a treatment for pregnancy-related symphyseal pain - A pilot randomized trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15(1).

Gupta A, Ceprnja D, Crosbie J. Does therapist-assisted exercise improve pregnancy related pelvic girdle pain? A randomised, cross-over, blinded, sham-controlled trial. Physiotherapy (United Kingdom). 2015;101:eS497.

Kibsgard TJ, Roise O, Stuge B. Pelvic joint fusion in patients with severe pelvic girdle pain - a prospective single-subject research design study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15:85.

Kuciel N, Sutkowska E, Cienska A, Markowska D, Wrzosek Z. Impact of Kinesio taping application on pregnant women suffering from pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain - preliminary study. Ginekol Pol. 2017;88(11):620–5.

Lund I, Lundeberg T, Lonnberg L, Svensson E. Decrease of pregnant women's pelvic pain after acupuncture: a randomized controlled single-blind study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2006;85(1):12–9.

Nilsson-Wikmar L, Holm K, Oijerstedt R, Harms-Ringdahl K. Effect of three different physical therapy treatments on pain and activity in pregnant women with pelvic girdle pain: a randomized clinical trial with 3, 6, and 12 months follow-up postpartum. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;30(8):850–6.

Ribnikar N, Scepanovic D, Verdenik I, Zgur L. Effect of pelvic belt and physiotherapy advice on pain in pregnant women with pelvic girdle pain. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2015;101:eS1306–eS7.

Stuge B, Laerum E, Kirkesola G, Vollestad N. The efficacy of a treatment program focusing on specific stabilizing exercises for pelvic girdle pain after pregnancy: a randomized controlled trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2004;29(4):351–9.

Vaidya S. Sacroiliac joint mobilisation versus transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for pregnancy induced posterior pelvic pain-a randomised clinical trial. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research. 2018;12(1):Yc04–yc7.

Weil YA, Hierholzer C, Sama D, Wright C, Nousiainen MT, Kloen P, et al. Management of persistent postpartum pelvic pain. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2008;37(12):621–6.

Bromley R, Bagley P. Should all women with pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain be treated with exercise? J Assoc Chart Physiother Womens Health. 2014;115:5–13.

Gausel A, Kjaermann I, Malmqvist S, Andersen K, Dalen I, Larsen J, et al. Chiropractic management of dominating one-sided pelvic girdle pain in pregnant women; a randomized controlled trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(1).

Cameron L, Marsden J, Watkins K, Freeman J. Management of antenatal pelvic-girdle pain study (MAPS): a single centred blinded randomised trial evaluating the effectiveness of two pelvic orthoses. Prosthetics Orthot Int. 2015;39:447.

Cameron L, Freeman J, Marsden J. Management of chronic post-partum pelvic girdle pain: evaluating effectiveness of combined physiotherapy and a dynamic elastomeric fabric orthosis. Physiotherapy (United Kingdom). 2017;103:e73–e4.

Clarkson C, Adams N, Caplin N. Korean hand acupuncture for pregnancy related pelvic girdle pain: a feasibility study. Physiotherapy. 2016;102:e202–e3.

Depledge J, McNair P, Keal-Smith C, Williams M. Management of symphysis pubis dysfunction during pregnancy using exercise and pelvic support belts. Phys Ther. 2005;85(12):1290–300.

Robinson HS, Balasundaram AP. Effectiveness of physical therapy interventions for pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain (PEDro synthesis). Br J Sports Med. 2017;52:1215–6.

Almousa S, Lamprianidou E, Kitsoulis G. The effectiveness of stabilising exercises in pelvic girdle pain during pregnancy and after delivery: a systematic review. Physiother Res Int. 2018;23(1).

Ostgaard H, Zetherström G, Roos-Hansson E, Svanberg B. Reduction of back and posterior pelvic pain in pregnancy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1994;19(8):894–900.

McIntyre IN, Broadhurst NA. Effective treatment of low back pain in pregnancy. Aust Fam Physician. 1996;25(9 Suppl 2):S65–7.

Hilde G, Gutke A, Slade SC, Stuge B. Physical therapy interventions for pelvic girdle pain (PGP) after pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(11):Cd012441.

Stafne S, Salvesen K, Romundstad P, Stuge B, Mørkved S. Does regular exercise during pregnancy influence lumbopelvic pain? A randomized controlled trial. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2012;91(5):552–9.

Young G, Jewell D. Interventions for preventing and treating pelvic and back pain in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(1):Cd001139.

Pennick VE, Young G. Interventions for preventing and treating pelvic and back pain in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(2):Cd001139.

Fisseha B, Mishra PK. The effect of group training on pregnancy-induced lumbopelvic pain: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized control trials. J Exerc Rehabil. 2016;12(1):15–20.

Norén L, Ostgaard S, Nielsen T, Ostgaard H. Reduction of sick leave for lumbar back and posterior pelvic pain in pregnancy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1997;22(18):2157–60.

Vas J, Aranda-Regules J, Modesto M, Aguilar I, Baron-Crespo M, Ramos-Monserrat M, et al. Auricular acupuncture for primary care treatment of low back pain and posterior pelvic pain in pregnancy: study protocol for a multicentre randomised placebo-controlled trial. Trials. 2014;15(1).

Kalus S, Kornman L, Quinlivan J. Managing back pain in pregnancy using a support garment: a randomised trial. BJOG. 2008;115(1):68–75.

Abu MA, Abdul Ghani NA, Shan LP, Sulaiman AS, Omar MH, Ariffin MHM, et al. Do exercises improve back pain in pregnancy? Horm Mol Biol Clin Investig. 2017;32(3).

Martins R, Pinto eSJ. An exercise method for the treatment of lumbar and posterior pelvic pain in pregnancy. J Altern Complement Med. 2005;27(5):275–82.

Schwerla F, Rother K, Rother D, Ruetz M, Resch K. Osteopathic manipulative therapy in women with postpartum low back pain and disability: a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. JAOA. 2015;115(7):416–25.

Miquelutti M, Cecatti J, Makuch M. Evaluation of a birth preparation program on lumbopelvic pain, urinary incontinence, anxiety and exercise: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2013;13:154.

Gutke A, Sjodahl J, Oberg B. Specific muscle stabilizing as home exercises for persistent pelvic girdle pain after pregnancy: a randomized, controlled clinical trial. J Rehabil Med. 2010;42(10):929–35.

Oh H, Lee Y, Shim M, Kim J. Effects of a postpartum back pain relief program for Korean women. Taehan Kanho Hakhoe Chi. 2007;37(2):163–70.

Franke H, Franke JD, Belz S, Fryer G. Osteopathic manipulative treatment for low back and pelvic girdle pain during and after pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2017;21(4):752–62.

Wang S, Dezinno P, Lin E, Lin H, Yue J, Berman M, et al. Auricular acupuncture as a treatment for pregnant women who have low back and posterior pelvic pain: a pilot study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201(3):271.e1–9.

Al-Sayegh NA, George SE, Boninger ML, Rogers JC, Whitney SL, Delitto A. Spinal mobilization of postpartum low back and pelvic girdle pain: an evidence-based clinical rule for predicting responders and nonresponders. Pm R. 2010;2(11):995–1005.

Close C, Sinclair M, Cullough J, Liddle D, Hughes C. A pilot randomised controlled trial (RCT) investigating the effectiveness of reflexology for managing pregnancy low back and/or pelvic pain. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2016;23:117–24.

Kaplan, Alpayci M, Karaman E, Çetin O, Özkan Y, lter S, et al. Short-term effects of Kinesio taping in women with pregnancy-related low back pain: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Medical Science Monitor. 2016;22:1297–301.

Kordi R, Abolhasani M, Rostami M, Hantoushzadeh S, Mansournia M, Vasheghani-Farahani F. Comparison between the effect of lumbopelvic belt and home based pelvic stabilizing exercise on pregnant women with pelvic girdle pain; a randomized controlled trial. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2013;26(2):133–9.

Kvorning N, Holmberg C, Grennert L, Aberg A, Akeson J. Acupuncture relieves pelvic and low-back pain in late pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2004;83(3):246–50.

Mirmolaei ST, Ansari NN, Mahmoudi M, Ranjbar F. Efficacy of a physical training program on pregnancy related lumbopelvic pain. Int J Womens Health Reprod Sci. 2018;6(2):161–6.

Mohamed EA, El-Shamy FF, Hamed H. Efficacy of kinesiotape on functional disability of women with postnatal back pain: a randomized controlled trial. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2018;31(1):205–10.

Ozdemir S, Bebis H, Ortabag T, Acikel C. Evaluation of the efficacy of an exercise program for pregnant women with low back and pelvic pain: a prospective randomized controlled trial [with consumer summary]. J Adv Nurs. 2015;71(8):1926–39.

Tseng PC, Puthussery S, Pappas Y, Gau ML. A systematic review of randomised controlled trials on the effectiveness of exercise programs on Lumbo pelvic pain among postnatal women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:316.

Wedenberg K, Moen B, Norling A. A prospective randomized study comparing acupuncture with physiotherapy for low-back and pelvic pain in pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2000;79(5):331–5.

Wiesner A, Gunther-Borstel J, Liem T, Ciranna-Raab C, Schmidt T. Osteopathic intravaginal treatment in pregnant women with low back pain. Int Urogynecol J. 2017;28(1 Supplement 1):S115.

Yao X, Li C, Ge X, Wei J, Luo J, Tian F. Effect of acupuncture on pregnancy related low back pain and pelvic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2017;10(4):5903–12.

Kluge J, Hall D, Louw Q, Theron G, Grove D. Specific exercises to treat pregnancy-related low back pain in a South African population. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2011;113(3):187–91.

George J, Skaggs C, Thompson P, Nelson D, Gavard J, Gross G. A randomized controlled trial comparing a multimodal intervention and standard obstetrics care for low back and pelvic pain in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;208(4):295.e1–7.

Foster N, Bishop A, Bartlam B, Ogollah R, Barlas P, Holden M, et al. Evaluating Acupuncture and Standard carE for pregnant women with Back pain (EASE Back): a feasibility study and pilot randomised trial. Health Technol Assess (Winchester, England). 2016;20(33):1–236.

Peterson C, Haas M, Gregory W. A pilot randomized controlled trial comparing the efficacy of exercise, spinal manipulation, and neuro emotional technique for the treatment of pregnancy-related low back pain. BMC Chiropractic & Manual Therapies. 2012;20.

Gross G, George J, Thompson P, Nelson D, Skaggs C. A randomized controlled trial comparing a multi-modal intervention and standard obstetrical care for low back and pelvic pain in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(1 suppl. 1):S360.

Eggen M, Stuge B, Mowinckel P, Jensen K, Hagen K. Can supervised group exercises including ergonomic advice reduce the prevalence and severity of low back pain and pelvic girdle pain in pregnancy? A randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther. 2012;92(6):781–90.

Murphy DR, Hurwitz EL, McGovern EE. Outcome of pregnancy-related lumbopelvic pain treated according to a diagnosis-based decision rule: a prospective observational cohort study. J Manip Physiol Ther. 2009;32(8):616–24.

Peterson CK, Muhlemann D, Humphreys BK. Outcomes of pregnant patients with low back pain undergoing chiropractic treatment: a prospective cohort study with short term, medium term and 1 year follow-up. Chiropr Man Therap. 2014;22(1):15.

Sklempe KI, Ivanisevic M, Uremovic M, Kokic T, Pisot R, Simunic B. Effect of therapeutic exercises on pregnancy-related low back pain and pelvic girdle pain: secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial. J Rehabil Med. 2017;49(3):251–7.

Ee CC, Manheimer E, Pirotta MV, White AR. Acupuncture for pelvic and back pain in pregnancy: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(3):254–9.

Barkatsa V, Wozniak G, Syrmos N, Iliadis C, Roupa Z. Intervetions for pelvic girdle pain in pregnant women. Bone. 2010;47:S237.

Pennick V, Liddle SD. Interventions for preventing and treating pelvic and back pain in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(8):Cd001139.

Stuge B, Hilde G, Vollestad N. Physical therapy for pregnancy-related low back and pelvic pain: a systematic review. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2003;82(11):983–90.

Shiri R, Coggon D, Falah-Hassani K. Exercise for the prevention of low back and pelvic girdle pain in pregnancy: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur J Pain. 2018;22(1):19–27.

van Benten E, Pool J, Mens J, Pool-Goudzwaard A. Recommendations for physical therapists on the treatment of lumbopelvic pain during pregnancy: a systematic review. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2014;44(7):464–73 a1.

Bennett RJ. Exercise for postnatal low back pain and pelvic pain. J Assoc Chart Physiother Womens Health. 2014;115:14–21.

Close C, Sinclair M, Liddle SD, Madden E, McCullough JE, Hughes C. A systematic review investigating the effectiveness of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) for the management of low back and/or pelvic pain (LBPP) in pregnancy. J Adv Nurs. 2014;70(8):1702–16.

Van Kampen M, Devoogdt N, De Groef A, Gielen A, Geraerts I. The efficacy of physiotherapy for the prevention and treatment of prenatal symptoms: a systematic review. Int Urogynecol J. 2015;26(11):1575–86.

Bastiaenen C, Bie R, Wolters P, Vlaeyen J, Bastiaanssen J, Klabbers A, et al. Treatment of pregnancy-related pelvic girdle and/or low back pain after delivery design of a randomized clinical trial within a comprehensive prognostic cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2004;4:67.

Ekdahl L, Petersson K. Acupuncture treatment of pregnant women with low back and pelvic pain--an intervention study. Scand J Caring Sci. 2010;24(1):175–82.

Sedaghati P, Ziaee V, Ardjmand A. The effect of an ergometric training program on pregnants weight gain and low back pain. Gazz Med Ital. 2007;166(6):209–13.

Ternov NK, Grennert L, Aberg A, Algotsson L, Akeson J. Acupuncture for lower back and pelvic pain in late pregnancy: a retrospective report on 167 consecutive cases. Pain Med. 2001;2(3):204–7.

Mørkved S, Salvesen K, Schei B, Lydersen S, Bø K. Does group training during pregnancy prevent lumbopelvic pain? A randomized clinical trial. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2007;86(3):276–82.

Granath A, Hellgren M, Gunnarsson R. Water aerobics reduces sick leave due to low back pain during pregnancy. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2006;35(4):465–71.

Butel T, Nicolian S, Durand M, Filipovic-Pierucci A, Kone M, Gambotti L, et al. Cost-effectiveness of acupuncture versus standard care for pelvic and low back pain in pregnancy: an analysis of the game randomized trial. Value Health. 2016;19(7):A588.

Haakstad LA, Bø K. Effect of a regular exercise programme on pelvic girdle and low back pain in previously inactive pregnant women: a randomized controlled trial. J Rehabil Med. 2015.

Ozdemir S, Bebis H, Ortabag T, Acikel C. Evaluation of the efficacy of an exercise program for pregnant women with low back and pelvic pain: a prospective randomized controlled trial. J Adv Nurs. 2015;71(8):1926–39.

van Zwienen CM, van den Bosch EW, Snijders CJ, van Vugt AB. Triple pelvic ring fixation in patients with severe pregnancy-related low back and pelvic pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2004;29(4):478–84.

Sehmbi H, D'Souza R, Bhatia A. Low back pain in pregnancy: investigations, management, and role of neuraxial analgesia and anaesthesia: a systematic review. Gynecol Obstet Investig. 2017;82(5):417–36.

Richards E, van Kessel G, Virgara R, Harris P. Does antenatal physical therapy for pregnant women with low back pain or pelvic pain improve functional outcomes? A systematic review. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2012;91(9):1038–45.

Hall H, Cramer H, Sundberg T, Ward L, Adams J, Moore C, et al. The effectiveness of complementary manual therapies for pregnancy-related back and pelvic pain: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(38):e4723.

Elden H, Ostgaard H, Fagevik-Olsen M, Ladfors L, Hagberg H. Treatments of pelvic girdle pain in pregnant women: adverse effects of standard treatment, acupuncture and stabilising exercises on the pregnancy, mother, delivery and the fetus/neonate. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2008;8:34.

Daly JM, Frame PS, Rapoza PA. Sacroiliac subluxation: a common, treatable cause of low-back pain in pregnancy. Fam Pract Res J. 1991;11(2):149–59.

Schep N, Haverlag R, Vugt A. Computer-assisted versus conventional surgery for insertion of 96 cannulated iliosacral screws in patients with postpartum pelvic pain. J Trauma. 2004;57(6):1299–302.

Elden H, Gutke A, Kjellby-Wendt G, Fagevik-Olsen M, Ostgaard HC. Predictors and consequences of long-term pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain: a longitudinal follow-up study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2016;17:276.

Bjelland EK, Stuge B, Engdahl B, Eberhard-Gran M. The effect of emotional distress on persistent pelvic girdle pain after delivery: a longitudinal population study. BJOG. 2013;120(1):32–40.

Gutke A, Josefsson A, Oberg B. Pelvic girdle pain and lumbar pain in relation to postpartum depressive symptoms. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32(13):1430–6.

The Cochrane Collaboration. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. 2011. Available from: http://www.handbook.cochrane.org.

Ioannidis JA, Evans SW, Gøtzsche PC, et al. Better reporting of harms in randomized trials: an extension of the consort statement. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(10):781–8.

Chiarotto A, Deyo RA, Terwee CB, Boers M, Buchbinder R, Corbin TP, et al. Core outcome domains for clinical trials in non-specific low back pain. Eur Spine J. 2015;24(6):1127–42.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the steering committee of the PGP-COS study for their input in the protocol of this review.

Funding

Maggie O’Donovan was supported by a Health Research Board Trials Methodology Research Network Summer Student Scholarship (Ireland). The funding body had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FW designed the review protocol with input from the PGP-COS study steering committee (acknowledged below). FW conducted the literature search. FW and MO conducted the study selection, quality assessment and data extraction. MO conducted the analysis under supervision of FW. All authors drafted, read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.

Search strategy. A detailed outline of the search strategy of this systematic review including the databases searched and exact search terms used.

Additional file 2.

Charateristics of included studies. A detailed description of the studies/systematic reviews that were included in this systematic review.

Additional file 3.

Quality of reporting. The results of the assessment of the quality of reporting in the individual studies included in this systematic review.

Additional file 4.

Comparison of outcomes identified in PGP and LPP studies for each core domain. The outcomes that were identified in studies examining PGP only are compared to the outcomes identified in studies including patients with LPP. This comparison has been presented by core domain.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Wuytack, F., O’Donovan, M. Outcomes and outcomes measurements used in intervention studies of pelvic girdle pain and lumbopelvic pain: a systematic review. Chiropr Man Therap 27, 62 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12998-019-0279-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12998-019-0279-2