Abstract

Background

Arthritis is a significant contributor to illness, pain and disability and imposes a considerable burden upon the community. Pain is a cardinal symptom of arthritis and has significant implications on biopsychosocial wellbeing. The multidimensional nature of the experience of pain in arthritis has not been well defined in community-based samples.

Aims

The two aims of this study are to generate profiles of pain from a community sample of older women and to compare profiles for women with and without arthritis.

Methods

The sub study is a cross-sectional postal survey of 700 Australian community-based women. The survey includes a range of measures on health, arthritis and pain that will be used to examine the multidimensional nature of the experience of pain in arthritis and generate profiles of pain.

Discussion

With no core set of measures for the evaluation of arthritis pain, this survey was created from an amalgamation of measures to capture multiple dimensions of pain. Findings from this study will assist in defining the symptom of pain in arthritis and may lead to further research in evidence-based treatment options for people with arthritis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Arthritis is a major contributor to individual illness, pain and disability and imposes a significant social and economic burden on the community [[1]]. Arthritis is common among older people, with at least 50% of people over the age of 65 having clinical arthritis [[2]]. Arthritis is also more common in women, with 50% of Australian women aged over 85 years reporting symptomatic osteoarthritis [[3]]. In 2005, 56% of Australians who reported arthritis as their main disabling condition reported chronic or recurrent pain [[4]]. Arthritis pain, whether acute or chronic, is the key disabling symptom of this disease [[5]].

Pain is an internal, subjective experience that cannot be directly observed by others and therefore assessment relies upon self-report [[6]]. The experience of pain in arthritis is multi-dimensional in nature, encompassing dimensions such as intensity, quality, location, frequency, duration, variability, and trajectory; as well as onset, mechanism, aetiology, sensory and affective qualities, exacerbating or alleviating factors, activity limitations, and effect on sleep [[7]-[11]]. Biopsychosocial aspects such as biological ageing, attitudes, beliefs, coping, expectations, prior experiences, fear, mood, presence and response of social support, and social context are among the many variables that will influence an individuals experience and report of pain [[10],[12]]. These dimensions and aspects of pain should be considered in the assessment of pain in people with arthritis. Notably Melzack and Casey defined three dimensions of pain: sensory-discriminative, affective-motivational and cognitive-evaluative [[13],[14]]. Each dimension has differing neural circuitry involved in processing, with the nociceptive, limbic and frontal cerebral cortex involved in each dimension respectively [[14]]. This model for the dimensions of pain is widely accepted, and whilst termed in the 1960’s, is still relevant to the experience of pain today.

The experience of pain in osteoarthritis is not well understood [[15]] nor captured by existing measures [[16]]. The assessment of osteoarthritis pain in clinical trials is mostly one dimensional, limited to the measure of pain intensity [[17]]. The Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI) has invited further research into the experience of pain in arthritis [[18]]. Of interest is the mechanism of central sensitization and neuropathic pain in arthritis. Acute, painful activation of the nociceptive pain pathway instigates a cascade of inflammatory and hyperalgesic substances in the joint [[19]]. Repeated, persistent excitation results in the peripheral sensitisation of surrounding musculoskeletal structures [[20]], modifying neuronal activity arriving at the spinal cord dorsal laminae. This leads to altered gene expression and central sensitisation [[21],[22]]. Central sensitisation causes increases in neuronal excitability and decreases inhibition of painful sensory input which results in altered responses of the nervous system [[23],[24]]. Modulation of the sensory response can cause plasticity of the nervous system, and result in what is now being recognised as the occurrence of neuropathic pain in arthritis [[25]]. A subgroup of people with osteoarthritis have been recognised as having troubling persistent pain and lower pain thresholds, as well as experiencing enhanced duration and temporal summation of pain [[25]]. This study highlights local and central sensitization as important underlying pain mechanisms in the experience of pain in knee OA. Increased pin-prick hyperalgesia has also been shown in people with rheumatoid arthritis [[26]]. A psychophysical and functional magnetic resonance imaging of a cohort of people with hip osteoarthritis found significantly lower pain thresholds than the general population in response to noxious stimuli in referred pain areas [[27]]. Gwilym et al. demonstrated increased activity in the periaqueductal grey matter associated with pin-prick stimulus [[27]]. Such evidence advocates for further research on the role of neuropathic pain in the traditionally peripheral disease of arthritis. Research is warranted to investigate the multidimensional nature of the experience of pain, and findings may have significant implications for the improvement of pharmacological responses and therapeutic outcomes in people who have arthritis [[28]].

The two aims of this study are to generate profiles of pain from a community sample of older women and to compare profiles for women with and without arthritis. Factors associated with different profiles of pain will be identified and the role of arthritis as a modifier will be investigated. It is hypothesized that women will group into unique profiles based on their multidimensional experience of pain.

Methods

The Australian longitudinal study on womens health

ALSWH is a longitudinal population-based survey which has been studying the health of a national sample of over 40 000 Australian women since 1996. This survey examines the relationships between biological, psychological, social and lifestyle factors and women’s physical health, emotional well-being and their use of and satisfaction with health care. Detailed methods for the recruitment and maintenance of the ALSWH cohorts have been described elsewhere [[29],[30]] and are available at http://www.alswh.org.au.

Profile of pain in older women Sub study

ALSWH participants are often invited to answer additional surveys between the major three yearly surveys. These smaller, separately funded sub studies have specific aims to investigate particular areas of health beyond the questions asked in the main surveys. The sample for this sub study consists of community-based women from the 1946–1951, mid aged cohort. Arthritis was found to be common in this group, with 32% of women reporting arthritis in 2006 when they were aged between 55–66 years [[31]]. In 2010, when the mid-aged cohort was aged between 59–64 years 17.9% of women reported osteoarthritis, 4.7% reported rheumatoid arthritis and 13.3% reported ‘other’ arthritis [[32]]. In 2012, at the time of the sub study survey, women from the mid-aged cohort will be aged 61–66 years.

A postal survey will be sent to two sub-samples of the 1946–51 cohort. One subsample will consist of 350 random women who answered ‘yes’ to “arthritis/rheumatism”, for the item “In the past THREE years, have you been diagnosed or treated for:” in ALSWH Survey 3 (2001) or ALSWH Survey 4 (2004). The other subsample will consist of 350 random women who have never reported any form of arthritis in ALSWH Surveys 3–6 (2001–2010). An information letter and survey will be sent to women; those who wish to participate are instructed to provide written consent, complete the survey and return it to the ALSWH office. The survey materials will be scanned and stored electronically at the University of Newcastle, Australia.

Profile of pain in older women Sub study survey

The survey will use measures of health, arthritis and pain as recommended by international bodies OARSI and Outcome Measures in Rheumatology (OMERACT) [[15],[18],[33]-[41]], and reports from expert panels [[12]]. The measures and their appropriateness for inclusion are discussed below (see Table 1).

Health measures

Health measures include the Medical Outcomes Study: 36 Item Short Form Survey (SF-36), Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) and Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS). The SF-36 is a self-report, 36 item survey measuring health-related quality of life [[42]], recommended where a detailed and broad ranging assessment of health is required. It is specifically applicable for this study as it will examine changes in health status over time [[43]]. The HAQ is the most widely used general functional measure in rheumatology [[44],[45]], specifically developed for use among adults with arthritis [[46],[47]]; it shows a strong correlation with physical capacity in older adults [[48]], and is supported for use in observational studies [[44]]. The FSS measures the impact of fatigue in a variety of rheumatologic and neurologic disorders [[49],[50]], and will enable comparison of fatigue symptomatology in populations of older women with arthritis [[51]].

Arthritis measures

Arthritis specific measures in the sub study survey include the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (WOMAC), Australian/Canadian (AUSCAN) Osteoarthritis Hand Index and the quickDASH. The WOMAC assesses health status and health outcomes in women who have arthritis of the knee and/or hip [[52]]. It is a health measurement tool which is valid, reliable and responsive, easy to complete and simple to score [[53]]. The AUSCAN Osteoarthritis Hand Index and quickDASH (Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand) will assess health status and health outcomes in arthritis of the upper limb (shoulder, elbow, wrist and hand) [[54]-[59]].

Pain measures

Pain measures will include the McGill Pain Questionnaire (Short Form) (SF-MPQ), Brief Pain Inventory (BPI), Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS), Graded Chronic Pain-Primary Care Scale (GCP-PCS) and the painDETECT. The SF-MPQ is a short form of the McGill Pain Questionnaire that will be used to assess the affective and sensory qualities of arthritis pain [[60]]. It is the most widely used, accepted and comprehensive assessment of the pain experience in older persons [[12],[61]-[63]]. The BPI allows patients to rate the severity of their pain and measure pain severity and interference on daily activities, including sleep [[64]]. First versions were developed for patients with rheumatoid arthritis [[65]], and reliability, validity and responsiveness has since been confirmed for patients with osteoarthritis [[66]-[68]]. The BPI is a measure recommended by an interdisciplinary consensus of experts to measure pain [[12],[62]]. The PCS was developed to assess three components of catastrophizing: rumination, magnification, and helplessness [[69]]. Pain catastrophizing is significantly related to pain outcomes in patients with rheumatoid arthritis [[70]], osteoarthritis [[71]] and neuropathic pain [[72]], with higher scores predicting chronicity [[73]]. The GCP-PCS will be used to obtain measures of chronic pain intensity, interference with activities and pain duration, as well as an ordinal classification of chronic pain severity [[74]]. The painDETECT has been selected as a measure of neuropathic pain components. It was initially developed and validated in 8000 low back pain patients [[75]] and has been used in studies for arthritis [[27],[76]-[79]].

Dimensions of pain

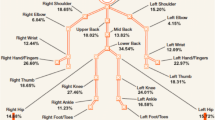

The measures of health, arthritis and pain have also been chosen to assess the multi-dimensional nature as pain as defined by Melzack and Casey [[13],[14]]. Sensory-discriminative dimensions of pain to be assessed include the location, intensity, severity, sensory and affective qualities, duration, course or variability and frequency. Affective-motivational dimensions of pain to be assessed include mood, catastrophizing, fatigue, interference and affect on sleep. Cognitive-evaluative dimensions of pain to be assessed include role social and role emotional. The measures used to assess these dimensions can be seen in Table 1.

The Australian longitudinal study on womens health linked data

For all consenting women, data from ALSWH Survey 6 (2010) will be accessed and linked to the sub study survey data. Linked survey information will include: body mass index; care information; cognition; conditions and comorbidities; demographic information; education and employment; health care utilization; health measures; life satisfaction; lifestyle choices; marital status; medical history; medication use; physical activity; psychological wellbeing; residency and retirement; social ability; and stiff and painful joint data.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics will be used to characterize the demographic, health and pain characteristics of women with and without arthritis, and groups will be compared with x2 tests and t tests as appropriate. Descriptive profiles of pain will be generated across the sample using latent class analysis. Associations between risk factors and health, arthritis, and pain profile will be evaluated by appropriate regression methods.

Ethics, funding and dissemination

This study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Newcastle; Approval number: H-2012-0144. Funding for this project was competitively gained through peer-review from Hunter Medical Research Institute. The findings of the study will be disseminated through peer-reviewed journals, national and international conference presentations.

Discussion

This is a large, cross-sectional sub study of 700 older women that will gather data on the multi-dimensional nature of the experience of pain in arthritis. With no core set of measures to evaluate the spectrum of arthritis pain beyond intensity and disability [[18]] this study amalgamated measures to capture individual dimensions of pain needed to describe different profiles of pain. Whilst intensity is the most common dimension of pain measured, it is important to measure the different qualities of pain. While focus groups have begun to analyze pain qualities in people with osteoarthritis, with several different studies reporting various descriptors of pain [[7],[79]-[81]], pain quality has not been assessed in population based studies of arthritis. This study will use stand-alone measures of pain, the SF-MPQ and painDETECT, to assess the sensory, affective and neuropathic qualities of pain. Dimensions other than intensity, severity and quality will also be explored. Previous studies have identified constant and intermittent pain, [[15]] the impact of beliefs on pain [[82]] and coping strategies, impact and severity perceptions) [[7]]. This study will use measures to assess pain onset and frequency, course or variability, fatigue, catastrophizing, sleep, social relations and the role of emotion. Multiple dimensions of pain are to be explored and analyzed, and these dimensions will be taken into consideration to group women to define “profiles” of pain. Recent work has investigated the psychological profiles in persons with knee osteoarthritis and found homogenous profiles with unique sets of characteristics [[83]]. Women with arthritis may also group into unique profiles based on their multidimensional experience of pain. This would be the first time.

Conclusion

This study will investigate the multi-dimensional nature of the experience of pain in arthritis using a sub study survey of a large cohort of older, community based women in Australia. With no core set of measures for the evaluation of arthritis pain, this survey was created from an amalgamation of measures of health, arthritis and pain to capture multiple dimensions of pain. It will allow generation of profiles of pain in community dwelling older women, and comparisons will be made between women with and without arthritis. Findings from this study will assist in defining the disease state of arthritis and may lead to further research in evidence-based treatment options for people with arthritis.

Abbreviations

- ALSWH:

-

Australian Longitudinal Study on Womens Health survey

- AUSCAN:

-

Australian/Canadian Osteoarthritis Hand

- BPI:

-

Brief pain inventory

- FSS:

-

Fatigue severity scale

- GCP-PCS:

-

Graded chronic pain-primary care scale

- HAQ:

-

Health Assessment Questionnaire

- OARSI:

-

Osteoarthritis Research Society International

- OMERACT:

-

Outcome measures in rheumatology

- PCS:

-

Pain catastrophizing scale

- SF-36:

-

Medical Outcomes Study: 36 Item Short Form Survey

- WOMAC:

-

Western Ontario and MacMaster Universities Arthritis Index

References

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare: Australia’s Health 2004. Canberra; 2004.

Helmick CG, Felson DT, Lawrence RC, Gabriel S, Hirsch R, Kwoh CK, Liang MH, Kremers HM, Mayes MD, Merkel PA, Pillemer SR, Reveille JD, Stone JH: Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part I Arthritis Rheum. 2008, 58 (1): 15-25. 10.1002/art.23177.

Parkinson L, Gibson R, Robinson I, Byles J: Older women and arthritis: tracking impact over time. Australas J Ageing. 2010, 29 (4): 155-160. 10.1111/j.1741-6612.2010.00422.x

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare: Arthritis and musculoskeletal conditions in Australia 2005. Canberra: 2005

McAlindon TE, Cooper C, Kirwan JR, Dieppe PA: Knee pain and disability in the community. Br J Rheumatol. 1992, 31 (3): 189-192. 10.1093/rheumatology/31.3.189

Correll D: The measurement of pain: Objectifying the subjective. Pain Management. Edited by: Waldman S. 2007, Elsevier Health Sciences, Philadelphia, 2,

French M, Wall A, Frankel L, Gignac M, Hawker G: Existing pain measures fail to capture the experience of pain in people with OA. J Rheumatol. 2006, 33: 377-

Nilsdotter AK, Toksvig-Larsen S, Roos EM: A 5 year prospective study of patient-relevant outcomes after total knee replacement. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2009, 17 (5): 601-606. 10.1016/j.joca.2008.11.007

Patt RB, Ellison NM: Breakthrough pain in cancer patients: characteristics, prevalence, and treatment. Oncology (Williston Park). 1998, 12 (7): 1035-1046. discussion 1049–1052,

Hawker GA: Experiencing painful osteoarthritis: what have we learned from listening?. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2009, 21 (5): 507-512. 10.1097/BOR.0b013e32832e99d7

Power JD, Perruccio AV, Badley EM: Pain as a mediator of sleep problems in arthritis and other chronic conditions. Arthritis Rheum. 2005, 53 (6): 911-919. 10.1002/art.21584

Hadjistavropoulos T, Herr K, Turk DC, Fine PG, Dworkin RH, Helme R, Jackson K, Parmelee PA, Rudy TE, Lynn Beattie B, Chibnall JT, Craig KD, Ferrell B, Ferrell B, Fillingim RB, Gagliese L, Gallagher R, Gibson SJ, Harrison EL, Katz B, Keefe FJ, Lieber SJ, Lussier D, Schmader KE, Tait RC, Weiner DK, Williams J: An interdisciplinary expert consensus statement on assessment of pain in older persons. Clin J Pain. 2007, 23 (1 Suppl): S1-S43. 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31802be869

Melzack R, Casey KL: Sensory, motivational, and central control determinants of pain. The Skin Senses. Edited by: Kenshalo D. 1968, 423-443. Charles C Thomas, Springfield,

Melzack R, Katz J: Pain. WIREs Cogn Sci. 2013, 4: 1-15. 10.1002/wcs.1201.

Hawker GA, Stewart L, French MR, Cibere J, Jordan JM, March L, Suarez-Almazor M, Gooberman-Hill R: Understanding the pain experience in hip and knee osteoarthritis–an OARSI/OMERACT initiative. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2008, 16 (4): 415-422. 10.1016/j.joca.2007.12.017

Woolhead GM, Donovan JL, Dieppe PA: Outcomes of total knee replacement: a qualitative study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2005, 44 (8): 1032-1037. 10.1093/rheumatology/keh674.

Croft P, Jordan K, Jinks C: “Pain elsewhere” and the impact of knee pain in older people. Arthritis Rheum. 2005, 52 (8): 2350-2354. 10.1002/art.21218

Lane NE, Brandt K, Hawker G, Peeva E, Schreyer E, Tsuji W, Hochberg MC: OARSI-FDA initiative: defining the disease state of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2011, 19 (5): 478-482. 10.1016/j.joca.2010.09.013

Wang XM, Hamza M, Wu TX, Dionne RA: Upregulation of IL-6, IL-8 and CCL2 gene expression after acute inflammation: Correlation to clinical pain. Pain. 2009, 142 (3): 275-283. 10.1016/j.pain.2009.02.001

McDougall JJ: Arthritis and pain. Neurogenic origin of joint pain. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006, 8 (6): 220- 10.1186/ar2069

Caporali R, Cavagna L, Montecucco C: Pain in arthritis. Eur J Pain Suppl. 2009, 3: 123-127. 10.1016/j.eujps.2009.07.009.

Fitzcharles MA, Shir Y: New concepts in rheumatic pain. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2008, 34 (2): 267-283. 10.1016/j.rdc.2008.03.005

Woolf CJ: Central sensitization: implications for the diagnosis and treatment of pain. Pain. 2011, 152 (3 Suppl): S2-S15. 10.1016/j.pain.2010.09.030

Arning K, Baron R: Evaluation of symptom heterogeneity in neuropathic pain using assessments of sensory functions. Neurotherapeutics. 2009, 6 (4): 738-748. 10.1016/j.nurt.2009.07.002

Arendt-Nielsen L, Nie H, Laursen MB, Laursen BS, Madeleine P, Simonsen OH, Graven-Nielsen T: Sensitization in patients with painful knee osteoarthritis. Pain. 2010, 149 (3): 573-581. 10.1016/j.pain.2010.04.003

Morris VH, Cruwys SC, Kidd BL: Characterisation of capsaicin-induced mechanical hyperalgesia as a marker for altered nociceptive processing in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Pain. 1997, 71 (2): 179-186. 10.1016/S0304-3959(97)03361-7

Gwilym SE, Keltner JR, Warnaby CE, Carr AJ, Chizh B, Chessell I, Tracey I: Psychophysical and functional imaging evidence supporting the presence of central sensitization in a cohort of osteoarthritis patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2009, 61 (9): 1226-1234. 10.1002/art.24837

Hochman JR, French MR, Bermingham SL, Hawker GA: The nerve of osteoarthritis pain. Arthritis Care Res. 2010, 62 (7): 1019-1023. 10.1002/acr.20142.

Lee C: Cohort Profile: The Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health. Int J Epidemiol. 2005, 34 (5): 987-991. 10.1093/ije/dyi098

Brown WJ, Bryson L, Byles JE, Dobson AJ, Lee C, Mishra G, Schofield M: Women’s Health Australia: recruitment for a national longitudinal cohort study. Women Health. 1998, 28 (1): 23-40. 10.1300/J013v28n01_03

Byles J, Loxton D, Berecki-Gisolf J, Dolja-Gore X, Gibson R, Hockey R, Robinson I, Parkinson L, Adamson L, Lucke J, Powers J, Young A, Dobson A: Use and costs of medications and other health care resources: Findings from the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health. 2008, Newcastle, Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health,

Australian Longitudinal Study on Womens Health: Data Book – ALSWH 1946 – 51 cohort Survey 6 2010. Newcastle; 2010

Bond M, Davis A, Lohmander S, Hawker G: Responsiveness of the OARSI-OMERACT osteoarthritis pain and function measures. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2012, 20 (6): 541-547. 10.1016/j.joca.2012.03.001

Davis AM, Perruccio AV, Canizares M, Tennant A, Hawker GA, Conaghan PG, Roos EM, Jordan JM, Maillefert JF, Dougados M, Lohmander LS: The development of a short measure of physical function for hip OA HOOS-Physical Function Shortform (HOOS-PS): an OARSI/OMERACT initiative. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2008, 16 (5): 551-559. 10.1016/j.joca.2007.12.016

Dougados M, Hawker G, Lohmander S, Davis AM, Dieppe P, Maillefert JF, Gossec L: OARSI/OMERACT criteria of being considered a candidate for total joint replacement in knee/hip osteoarthritis as an endpoint in clinical trials evaluating potential disease modifying osteoarthritic drugs. J Rheumatol. 2009, 36 (9): 2097-2099. 10.3899/jrheum.090365

Gossec L, Hawker G, Davis AM, Maillefert JF, Lohmander LS, Altman R, Cibere J, Conaghan PG, Hochberg MC, Jordan JM, Katz JN, March L, Mahomed N, Pavelka K, Roos EM, Suarez-Almazor ME, Zanoli G, Dougados M: OMERACT/OARSI initiative to define states of severity and indication for joint replacement in hip and knee osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol. 2007, 34 (6): 1432-1435.

Gossec L, Paternotte S, Maillefert JF, Combescure C, Conaghan PG, Davis AM, Gunther KP, Hawker G, Hochberg M, Katz JN, Kloppenburg M, Lim K, Lohmander LS, Mahomed NN, March L, Pavelka K, Punzi L, Roos EM, Sanchez-Riera L, Singh JA, Suarez-Almazor ME, Dougados M: The role of pain and functional impairment in the decision to recommend total joint replacement in hip and knee osteoarthritis: an international cross-sectional study of 1909 patients. Report of the OARSI-OMERACT Task Force on total joint replacement. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2011, 19 (2): 147-154. 10.1016/j.joca.2010.10.025

Hawker GA, Davis AM, French MR, Cibere J, Jordan JM, March L, Suarez-Almazor M, Katz JN, Dieppe P: Development and preliminary psychometric testing of a new OA pain measure – an OARSI/OMERACT initiative. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2008, 16 (4): 409-414. 10.1016/j.joca.2007.12.015

Perruccio AV, Stefan Lohmander L, Canizares M, Tennant A, Hawker GA, Conaghan PG, Roos EM, Jordan JM, Maillefert JF, Dougados M, Davis AM: The development of a short measure of physical function for knee OA KOOS-Physical Function Shortform (KOOS-PS) - an OARSI/OMERACT initiative. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2008, 16 (5): 542-550. 10.1016/j.joca.2007.12.014

Davis AM, Lohmander LS, Wong R, Venkataramanan V, Hawker GA: Evaluating the responsiveness of the ICOAP following hip or knee replacement. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2010, 18 (8): 1043-1045. 10.1016/j.joca.2010.04.013

Ruyssen-Witrand A, Fernandez-Lopez CJ, Gossec L, Anract P, Courpied JP, Dougados M: Psychometric properties of the OARSI/OMERACT osteoarthritis pain and functional impairment scales: ICOAP. KOOS-PS and HOOS-PS Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2011, 29 (2): 231-237.

Ware J, Snow K, Kosinski M, Gandek B: Health Survey. Manual and interpretation guide. 1993, The Health Institute, New England Medical Center, Boston,

Schofield MJ, Mishra G: Validity of the SF-12 Compared with the SF-36 Health Survey in Pilot Studies of the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health. J Health Psychol. 1998, 3 (2): 259-271. 10.1177/135910539800300209

White DK, Wilson JC, Keysor JJ: Measures of adult general functional status: SF-36 Physical Functioning Subscale (PF-10), Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ), Modified Health Assessment Questionnaire (MHAQ), Katz Index of Independence in Activities of Daily Living, Functional Independ. Arthritis Care Res. 2011, 63 (S11): S297-S307. 10.1002/acr.20638.

Fries JF, Spitz PW, Young DY: The dimensions of health outcomes: the health assessment questionnaire, disability and pain scales. J Rheumatol. 1982, 9 (5): 789-793.

Fries JF, Spitz PW, Kraines RG, Holman HR: Measurement of patient outcome in arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1980, 23: 137-145. 10.1002/art.1780230202

Wolfe F, Kleinheksel SM, Cathey MA, Hawley DJ, Spitz PW, Fries JF: The clinical value of the Stanford Health Assessment Questionnaire Functional Disability Index in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1988, 15 (10): 1480-1488.

Daltroy LH, Larson MG, Eaton HM, Phillips CB, Liang MH: Discrepancies between self-reported and observed physical function in the elderly: the influence of response shift and other factors. Soc Sci Med. 1999, 48 (11): 1549-1561. 10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00048-9

Haldorsen K, Bjelland I, Bolstad AI, Jonsson R, Brun JG: A five-year prospective study of fatigue in primary Sjogren’s syndrome. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011, 13 (5): R167- 10.1186/ar3487

Hewlett S, Dures E, Almeida C: Measures of fatigue: Bristol Rheumatoid Arthritis Fatigue Multi-Dimensional Questionnaire (BRAF MDQ), Bristol Rheumatoid Arthritis Fatigue Numerical Rating Scales (BRAF NRS) for severity, effect, and coping, Chalder Fatigue Questionnaire (CFQ), Checklist Individual Strength (CIS20R and CIS8R), Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS), Functional Assessment Chronic Illness Therapy (Fatigue) (FACIT-F), Multi-Dimensional Assessment of Fatigue (MAF), Multi-Dimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI), Pediatric Quality Of Life (PedsQL) Multi-Dimensional Fatigue Scale, Profile of Fatigue (ProF), Short Form 36 Vitality Subscale (SF-36 VT), and Visual Analog Scales (VAS). Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011, 63 (Suppl 11): S263-S286. 10.1002/acr.20579.

Krupp LB, LaRocca NG, Muir-Nash J, Steinberg AD: The fatigue severity scale. Application to patients with multiple sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch Neurol. 1989, 46 (10): 1121-1123. 10.1001/archneur.1989.00520460115022

Bellamy N: WOMAC Osteoarthritis Index User Guide. 2002, Version V, Brisbane, Australia,

Bellamy N: The WOMAC Knee and Hip Osteoarthritis Indices: development, validation, globalization and influence on the development of the AUSCAN Hand Osteoarthritis Indices. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2005, 23 (5 Suppl 39): S148-S153.

Fayad F, Lefevre-Colau MM, Gautheron V, Mace Y, Fermanian J, Mayoux-Benhamou A, Roren A, Rannou F, Roby-Brami A, Revel M, Poiraudeau S: Reliability, validity and responsiveness of the French version of the questionnaire Quick Disability of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand in shoulder disorders. Man Ther. 2009, 14 (2): 206-212. 10.1016/j.math.2008.01.013

Bellamy N, Campbell J, Haraoui B, Buchbinder R, Hobby K, Roth JH, MacDermid JC: Dimensionality and clinical importance of pain and disability in hand osteoarthritis: Development of the Australian/Canadian (AUSCAN) Osteoarthritis Hand Index. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2002, 10 (11): 855-862. 10.1053/joca.2002.0837

Allen KD, Jordan JM, Renner JB, Kraus VB: Validity, factor structure, and clinical relevance of the AUSCAN Osteoarthritis Hand Index. Arthritis Rheum. 2006, 54 (2): 551-556. 10.1002/art.21615

Bellamy N, Campbell J, Haraoui B, Gerecz-Simon E, Buchbinder R, Hobby K, MacDermid JC: Clinimetric properties of the AUSCAN Osteoarthritis Hand Index: an evaluation of reliability, validity and responsiveness. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2002, 10 (11): 863-869. 10.1053/joca.2002.0838

Beaton DE, Wright JG, Katz JN: Development of the QuickDASH: comparison of three item-reduction approaches. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005, 87 (5): 1038-1046. 10.2106/JBJS.D.02060

Gummesson C, Ward MM, Atroshi I: The shortened disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand questionnaire (QuickDASH): validity and reliability based on responses within the full-length DASH. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2006, 7: 44- 10.1186/1471-2474-7-44

Melzack R: The short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire. Pain. 1987, 30 (2): 191-197. 10.1016/0304-3959(87)91074-8

Herr KA, Spratt K, Mobily PR, Richardson G: Pain intensity assessment in older adults: use of experimental pain to compare psychometric properties and usability of selected pain scales with younger adults. Clin J Pain. 2004, 20 (4): 207-219. 10.1097/00002508-200407000-00002

Melzack R: The McGill Pain Questionnaire: major properties and scoring methods. Pain. 1975, 1 (3): 277-299. 10.1016/0304-3959(75)90044-5

Bird J: Assessing pain in older people. Nurs Stand. 2005, 19 (19): 45-52. quiz 53–44,

Cleeland CS, Ryan KM: Pain assessment: global use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1994, 23 (2): 129-138.

Daut RL, Cleeland CS, Flanery RC: Development of the Wisconsin Brief Pain Questionnaire to assess pain in cancer and other diseases. Pain. 1983, 17 (2): 197-210. 10.1016/0304-3959(83)90143-4

Mendoza T, Mayne T, Rublee D, Cleeland C: Reliability and validity of a modified Brief Pain Inventory short form in patients with osteoarthritis. Eur J Pain. 2006, 10 (4): 353-361. 10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.06.002

Keller S, Bann CM, Dodd SL, Schein J, Mendoza TR, Cleeland CS: Validity of the brief pain inventory for use in documenting the outcomes of patients with noncancer pain. Clin J Pain. 2004, 20 (5): 309-318. 10.1097/00002508-200409000-00005

Williams VS, Smith MY, Fehnel SE: The validity and utility of the BPI interference measures for evaluating the impact of osteoarthritic pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006, 31 (1): 48-57. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.06.008

Sullivan MJL, Bishop S, Pivik J: The Pain Catastrophizing Scale: Development and validation. Psychol Assess. 1995, 7: 524-532. 10.1037/1040-3590.7.4.524.

Keefe FJ, Brown GK, Wallston KA, Caldwell DS: Coping with rheumatoid arthritis pain: catastrophizing as a maladaptive strategy. Pain. 1989, 37 (1): 51-56. 10.1016/0304-3959(89)90152-8

Keefe FJ, Kashikar-Zuck S, Robinson E, Salley A, Beaupre P, Caldwell D, Baucom D, Haythornthwaite J: Pain coping strategies that predict patients’ and spouses’ ratings of patients’ self-efficacy. Pain. 1997, 73 (2): 191-199. 10.1016/S0304-3959(97)00109-7

Sullivan MJ, Feuerstein M, Gatchel R, Linton SJ, Pransky G: Integrating psychosocial and behavioral interventions to achieve optimal rehabilitation outcomes. J Occup Rehabil. 2005, 15 (4): 475-489. 10.1007/s10926-005-8029-9

Sullivan MJ, Sullivan ME, Adams H: Stage of chronicity and the cognitive correlates of pain-related disability. Cog Behav Ther. 2002, 31: 111-118. 10.1080/165060702320337988.

Von Korff M, Dworkin SF, Le Resche L: Graded chronic pain status: an epidemiologic evaluation. Pain. 1990, 40 (3): 279-291. 10.1016/0304-3959(90)91125-3.

Freynhagen R, Baron R, Gockel U, Tolle TR: painDETECT: a new screening questionnaire to identify neuropathic components in patients with back pain. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006, 22 (10): 1911-1920. 10.1185/030079906X132488

Ohtori S, Orita S, Yamashita M, Ishikawa T, Ito T, Shigemura T, Nishiyama H, Konno S, Ohta H, Takaso M, Inoue G, Eguchi Y, Ochiai N, Kishida S, Kuniyoshi K, Aoki Y, Arai G, Miyagi M, Kamoda H, Suzkuki M, Nakamura J, Furuya T, Kubota G, Sakuma Y, Oikawa Y, Suzuki M, Sasho T, Nakagawa K, Toyone T, Takahashi K: Existence of a neuropathic pain component in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee. Yonsei Med J. 2012, 53 (4): 801-805. 10.3349/ymj.2012.53.4.801

Wu Q, Inman RD, Davis KD: Neuropathic pain in ankylosing spondylitis: a psychophysics and brain imaging study. Arthritis Rheum. 2013, 65 (6): 1494-1503. 10.1002/art.37920

Soni A, Batra RN, Gwilym SE, Spector TD, Hart DJ, Arden NK, Cooper C, Tracey I, Javaid MK: Neuropathic features of joint pain: a community-based study. Arthritis Rheum. 2013, 65 (7): 1942-1949. 10.1002/art.37962

Hochman JR, Gagliese L, Davis AM, Hawker GA: Neuropathic pain symptoms in a community knee OA cohort. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2011, 19 (6): 647-654. 10.1016/j.joca.2011.03.007

Gooberman-Hill R, Woolhead G, MacKichan F, Ayis S, Williams S, Dieppe P: Assessing chronic joint pain: Lessons from a focus group study. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2007, 57 (4): 666-671. 10.1002/art.22681.

Stamm T, van der Giesen F, Thorstensson C, Steen E, Birrell F, Bauernfeind B, Marshall N, Prodinger B, Machold K, Smolen J, Kloppenburg M: Patient perspective of hand osteoarthritis in relation to concepts covered by instruments measuring functioning: a qualitative European multicentre study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009, 68 (9): 1453-1460. 10.1136/ard.2008.096776

Hill S, Dziedzic K, Thomas E, Baker SR, Croft P: The illness perceptions associated with health and behavioural outcomes in people with musculoskeletal hand problems: findings from the North Staffordshire Osteoarthritis Project (NorStOP). Rheumatology. 2007, 46 (6): 944-951. 10.1093/rheumatology/kem015

Cruz-Almeida Y, King CD, Goodin BR, Sibille KT, Glover TL, Riley JL, Sotolongo A, Herbert MS, Schmidt J, Fessler BJ, Redden DT, Staud R, Bradley LA, Fillingim RB: Psychological profiles and pain characteristics of older adults with knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2013, 65 (11): 1786-1794. 10.1002/acr.22070.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Fiona Blyth and Dr. Henry Pollard are acknowledged for their contributions towards the design of the sub study survey, as well as secondary supervision of PhD student Katie de Luca. Prof. Gillian Hawker is acknowledged for her contribution to the design of the sub study survey. Dr. Lynn Francis is acknowledged for her contribution to planning the statistical analysis of the sub study. Mr. Thomas Lo and Ms. Anna Graves are acknowledged for their contribution to the administration of the sub study. The Hunter Medical Research Institute is acknowledged for funding of the sub study, supported by the Lions Club of Adamstown Research Project Grant. Author Katie de Luca is a full time University of Newcastle higher degree research student and acknowledges receipt of the Australian Postgraduate Award Scholarship and COCA Research Limited Top up Scholarship contributions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contribution

KD, LP and JB contributed to the conception of the project, design of the study and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

de Luca, K., Parkinson, L. & Byles, J. A study protocol for the profile of pain in older women: assessing the multi dimensional nature of the experience of pain in arthritis. Chiropr Man Therap 22, 28 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12998-014-0028-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12998-014-0028-5