Abstract

Background

Tick-borne phenuivirus (TBPVs) comprise human and animal viruses that can cause a variety of clinical syndromes ranging from self-limiting febrile illness to fatal haemorrhagic fevers.

Objective

Detect Phlebovirus (Family Phenuiviridae) in ticks collected from domestic animals in Córdoba, Colombia.

Methods

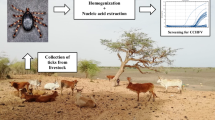

We collected 2365 ticks from domestic animals in three municipalities of the Department of Cordoba, Colombia in 2016. Ticks were identified and pooled by species for RNA extraction. A nested real-time PCR with specific primers for Phlebovirus and a specific probe for Heartland virus (HRTV) formerly a Phlebovirus, now a Banyangvirus were performed. Also, a conventional nested PCR, with the same specific primers was used to detect other Phleboviruses, with positive reactions indicated by an amplified cDNA fragment of approximately 244 bp determined by gel electrophoresis. These bands were gel-purified and sequenced by the Sanger method.

Results

Using real-time RT-PCR, no positive results for HRTV were found. However, using conventional nested PCR 2.2% (5/229 pools) yielded a product of 244 bp. One positive sample was detected in a pool of Dermacentor nitens ticks collected from a horse, and the four remaining positive pools were from Rhipicephalus microplus collected from cattle. The five positive nucleotide sequences had identities of 93 to 96% compared to a section of the L-segment of Lihan Tick virus, a Phlebovirus originally detected in R. microplus ticks in China. The strongest identity (96–99%) was with Lihan Tick virus detected in R. microplus ticks from Brazil.

Conclusions

This is the first report of viral detection in ticks in Colombia. We detected a Colombian strain of Lihan Tick virus. We recommend expanding the sampling area and carrying out more eco-epidemiological studies related to epidemiological surveillance of viruses on ticks in Colombia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Synopsis

Phleboviruses are RNA viruses transmitted by ticks, phlebotomines and mosquitoes. This study presents the first detection of Phlebovirus (Lihan Tick Virus) in ticks from Colombia. The sequences detected are related to Lihan Tick Virus previously reported in Brazil and China.

Background

Members of the family Phenuiviridae include human and animal pathogenic viruses transmitted by arthropod vectors, including phlebotomine sandflies, mosquitos and ticks [1, 2]. They can cause a variety of clinical syndromes ranging from a brief, self-limiting febrile illness, to retinitis, encephalitis, meningoencephalitis and fatal haemorrhagic fever [3]. The genus Phlebovirus belongs to the family Phenuiviridae, order Bunyavirales, [4]. The genus includes 10 species with around 58 viruses and several that have not yet been categorized [5]. Phlebovirus genomes are single-stranded RNA with negative polarity, organized into three segments. Segment L is approximately 6.4 kb and encodes an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, segment M is approximately 3.4 kb and encodes viral glycoproteins, and the S segment is approximately 1.7 kb and encodes the nucleocapsid protein. Additional non-stuctural proteins (NSS) are encoded on the S and M segments [3, 6, 7].

In 2018, TBPVs were divided into four phylogenetically related groups: i. the Uukuniemi group, which includes at least 17 species of tick-borne phleboviruses; ii. the severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus / Heartland virus group; iii. The Bhanja group; and iv. the Kaisodi group. Most of these viruses cause disease in humans [4].

However, in 2019, the group of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus / Heartland virus, was taxonomically reclassified in the genus Banyangvirus [5].

In recent years, new TBPVs capable of inducing serious diseases in humans have emerged.

In 2007, the first cases of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus (SFTSV), was found in China, later were reported in Japan, Korea and Vietman in patients with severe fever, thrombocytopenia and leukocytopenia accompanied by gastrointestinal symptoms, chills, joint pain and myalgia [8,9,10,11,12]. In the western hemisphere, Heartland virus (HRTV) was first isolated in 2009 from two patients in the state of Missouri, USA, who showed symptoms similar to those of SFTSV. HRTV is phylogenetically related to SFTSV with a similarity of 60 to 70% at the nucleotide level [13]. Amblyomma americanum ticks appear to be the main vector for HRTV transmission. To date, more than 30 cases of HRTV infection, including two deaths, have been reported in the United States [14,15,16]. The status of HRTV in subtropical and tropical regions of the Americas remains unknown.

In Colombia, ticks of the genus Ixodes, Dermacentor, Amblyomma, Haemaphysalis and Rhipicephalus could act as vectors for a variety of viruses including TBPVs [17]. However, there have been no studies looking for viruses in ticks to date. The aim of this study was to detect and identify HRTV and other TBPVs in ticks collected from domestic animals in different municipalities of the department of Córdoba, Colombia.

Methods

Type of study, geographic area and sampling sites

A descriptive and prospective cross-sectional study was conducted between June and December 2016. Ticks attached to dogs, horses, and cattle were collected in the municipalities of Montería, Cereté, San Pelayo and Puerto Escondido in the department of Córdoba, Colombia (Fig. 1). Córdoba is located in the northwestern part of Colombia from 7° 22′ to 9° 26′ north latitude and from 74° 47′ to 76° 30′ west longitude. Córdoba has a warm tropical climate, an average temperature of 28 °C, with altitude ranging from 0 to 40 m above sea level. Its principal economic activity is livestock, agriculture and in grazing, which is over exploited, affecting ecosystems and increasing the burden of ticks potentially responsible for the transmission of many zoonotic diseases [18].

Ticks collections and taxonomic identification

Hard ticks from the family Ixodidae were collected at all developmental stages by removing them from their vertebrate hosts. For storage and transport, ticks were placed in small containers with porous caps for oxygen exchange. Ticks identification was performed using the taxonomic dichotomous keys [19]. Once taxonomically identified, they were frozen at − 90 °C. Ticks were characterized by species, sex and stage and pooled by species, municipality, date and host. The prevalence of Phlebovirus in ticks was expressed as a minimum infection rate per 1000 ticks (MIR) based on the assumption that a PCR-positive pool contains at least one positive tick [20].

Phlebovirusdetection RNA extraction was carried out with PureLink® RNA Mini Kit combined with TRIzol® (Invitrogen). RNAs were reverse transcribed with Moloney Murine Leukemia Virus Reverse Transcriptase (M-MLV RT), random primers and amplified with nested PCR primers designed to amplify conserved Phlebovirus L segment sequence.

For the first round, a conventional PCR was carried out with the genus-specific primers: NPhlebo1f 2054-ATGGARGGITTTGTIWSICIICC-2074 and NPhlebo1r 2295-AARTTRCTIGWIGCYTTIARIGTIGC-2273. For the second round, real-time PCR was used with genus-specific nested primers: NPhlebo2f 2027-WTICCIAAICCIYMSAARATG-2049, NPhlebo2r 2578-TCYTCYTTRTTYTTRARRTARCC-2552 [21] and a FAM-labeled TaqmanTm probe 5′-CGAGTGGAATGGACAGGGAC-BHQ1–3′ for specific detection of HRTV. HRTV RNA was used as positive control. In addition, for the second round a conventional PCR, with the same specific primers was used to detect other Phleboviruses.

Sequencing and phylogenetic analysis

Positive samples were subject to direct sequence of both strands in independent reactions with each of the internal primers and analyzed by the Sanger method (Quintara Biosciences, Inc., Berkeley, CA, USA). Nucleotide sequences were subjected to a BLAST analysis to identify homologous sequences in GenBank. Twenty-six sequences of the L segment of different Phleboviruses were downloaded from GenBank and aligned using MUSCLE in MEGAX. The phylogenetic analysis was performed using the maximum likelihood method with Kimura 2 parameters model with MEGAX [22]..

Results

A total of 2365 ticks were collected, including 1358 (57.5%) R. microplus collected from bovines, 978 (41.3%) D. nitens collected from equines, and 29 (1.22%) Rhipicephalus sanguineus sensu lato collected from dogs. Ticks were organized in 229 pools.

Detection of viral RNA in ticks and sequencing analysis

We found that 2.2% of tick pool extracts (5/229) yielded PCR amplicons with the length expected from Phlebovirus species (244 bp). One amplicon was detected from 63 pools of D. nitens collected from equines (MIR 1.02; 1/978 ticks tested) and the other four amplicons were found among 144 pools of R. microplus collected from bovines (MIR of 2.95; 4/1358 ticks tested). None of 29 R. sanguineus ticks collected from dogs tested positive. No positive results for HRTV were found.

Alignments of the 244-bp amplicons showed that three of the sequences were identical and the other two sequences had small changes in the nucleotide sequences of 1 and 7 bases.

Sequencing and BLAST analysis showed that the five sequences detected have an identity between 93 to 96% with sequence from the Phlebovirus Lihan tick virus, L-segment, originally identified in R. microplus ticks in China [23] and identity between 96 to 99% with Lihan tick virus detected in R. microplus ticks in Brazil in 2018 [24]. Sequences were deposited in GenBank under the following accession numbers: MK040531, MN026336, MN026337, MN026338 and MN026339.

Phylogenetic analysis

A phylogenetic tree was constructed with the five sequences reported in this study and 19 related sequences available in the GenBank, as well as outlier sequences from tick and mosquito-borne viruses, Mukawa virus and Gouléako virus respectively (Fig. 2). The tick virus sequences detected in this study formed a clade with sequences of Lihan tick virus from Brazil and China. These viruses are most similar to other TBPVs and are distant from Phleboviruses transmitted by sandflies and mosquitoes.

Phylogenetic analysis of Colombian Lihan Tick virus. Evolutionary history was inferred by using the Maximum Likelihood method and Kimura 2-parameter model. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths measured in the number of substitutions per site. This analysis involved 26 nucleotide sequences. Bootstrap values were deduced from 1000 replicates. There was a total of 149 positions in the final dataset

Discussion

Ticks are transmitters of many viruses of importance in public health. However, viral diversity in ticks from South America is largely unknown [24]. In recent years the emergence of new TBPV such as SFTSV and HRTV in Asia and North America, respectively, present a significant public health threat [4]. In the present study, TBPV sequences detected in Colombian ticks collected form domestic animals were similar to Lihan tick virus detected in China in R. microplus ticks [23]. Our results also agree with a work carried out in Southern of Brazil by Souza et al., in 2018, who analyzed six groups of R. microplus ticks (~ 50 per group). They used a metagenomic approach with high-throughput sequencing (HTS) and detected Lihan tick virus in 5 of 6 groups of ticks [24]. Sameroff et al., 2019, conducted a study in Trinidad and Tobago in 2017 and 2018, in which they analyzed 638 ticks, including R. microplus (n = 320), R. sanguineus (n = 300) and A. ovale (n = 18) with HTS. Lihan tick virus was detected in 14 of 16 pools of R. microplus (MIR of 43.75; 14/320 ticks tested) results that differ from the MIR of 2.95 (4/1358) reported in our study. However, the methodology used for the detection of the Lihan tick virus in these two studies was different, and Sameroff et al. used 20 ticks per pool, whereas we tested pool sizes of 10–15. Furthermore, the stage and sex distribution of ticks and season of collection in the two studies may have differed. These differences as well as geographic variation could explain the variability in the results [25].

A limitation of the present study is the short fragment (less than 200 bp) of the L segment used for phylogenetic analysis. However, this segment is highly conserved and is the most used for phleboviruses phylogenetic studies [21, 26, 27]. Subsequent studies will amplify a larger fragment of the L segment and include the detection of S and M segments, to rule out reassortment of genome segments with other Phenuivirus, in addition to the use of new technologies such as HTS, to better characterize the Colombian viruses. This is the first report of a virus sequence detected in ticks from Colombia and the first Colombian detection of Lihan tick virus, a recently described virus with unknown pathogenicity. We suggest that detect of novel viral genomes in Colombia is important and that efforts to establish disease associations with these genomes is essential for One Health.

Availability of data and materials

The sequences of Lihan tick virus have been deposited into GenBank database under the accession numbers: MK040531, MN026336, MN026337, MN026338 and MN026339.

Abbreviations

- TBPV:

-

Tick-borne Phlebovirus

- HRTV:

-

Heartland virus

- SFTSV:

-

Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus

- RT-PCR:

-

Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

- bp:

-

base pairs

- MIR:

-

minimum infection rate

References

Matsuno K, Weisend C, Kajihara M, Matysiak C, Williamson BN, Simuunza M, et al. Comprehensive molecular detection of tick-borne Phleboviruses leads to the retrospective identification of taxonomically unassigned Bunyaviruses and the discovery of a novel member of the genus Phlebovirus. J Virol [Internet]. 2015;89(1):594–604. Available from: http://jvi.asm.org/lookup/doi/10.1128/JVI.02704-14.

Palacios G, Savji N, Travassos da Rosa A, Guzman H, Yu X, Desai A, et al. characterization of the Uukuniemi virus group (Phlebovirus: Bunyaviridae): evidence for seven distinct species. J Virol [Internet] 2013;87(6):3187–95. Available from: http://jvi.asm.org/cgi/doi/10.1128/JVI.02719-12.

Liu DY, Tesh RB, da Rosa APA T, Peters CJ, Yang Z, Guzman H, et al. Phylogenetic relationships among members of the genus Phlebovirus (Bunyaviridae) based on partial M segment sequence analyses. J Gen Virol. 2003;84(2):465–73.

Matsuno K, Kajihara M, Nakao R, Nao N, Mori-Kajihara A, Muramatsu M, et al. The Unique Phylogenetic Position of a Novel Tick-Borne Phlebovirus Ensures an Ixodid Origin of the Genus Phlebovirus. mSphere [Internet]. 2018;3(3):1–14. Available from: http://msphere.asm.org/lookup/doi/10.1128/mSphere.00239-18.

Maes P, Adkins S, Alkhovsky SV, Avšič T, Matthew Ž. Taxonomy of the order Bunyavirales: second update 2018. Virol Div news. 2019;164:927–41.

Mazelier M, Rouxel RN, Zumstein M, Mancini R, Bell-Sakyi L, Lozach P-Y. Uukuniemi Virus as a Tick-Borne Virus Model. J Virol [Internet]. 2016;90(15):6784–98. Available from: http://jvi.asm.org/lookup/doi/10.1128/JVI.00095-16.

Moriconi M, Rugna G, Calzolari M, Bellini R, Albieri A, Angelini P, et al. Phlebotomine sand fly–borne pathogens in the mediterranean basin: human leishmaniasis and phlebovirus infections. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11(8):1–19.

Xu B, Liu L, Huang X, Ma H, Zhang Y, Du Y, et al. Metagenomic analysis of fever, thrombocytopenia and leukopenia syndrome ( FTLS ) in Henan Province, China : discovery of a new Bunyavirus. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7(11):1–10.

Matsumoto N, Masuoka H, Hirayama K, Yamada A, Hotta K. Detection and phylogenetic analysis of phlebovirus, including severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus, in ticks collected from Tokyo, Japan. J Vet Med Sci. 2018;80(4):638–41.

Yu KM, Yu MA, Park SJ, Kim YIL, Robles NJ, Kwon H IL, et al. Seroprevalence and genetic characterization of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus in domestic goats in South Korea. Ticks Tick Borne Dis [Internet]. 2018;9(5):1202–6. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ttbdis.2018.05.001.

Huang X, Ding S, Jiang X, Pang B, Zhang Q, Li C, et al. Detection of SFTS virus RNA and antibodies in severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome surveillance cases in endemic areas of China. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19(476):2–6.

Tran XC, Yun Y, Van An L, Kim S-H, Thao NTP, Man PKC, et al. Endemic severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome. Vietnam Emerg Infect Dis. 2019;25(5):1029–31.

McMullan LK, Folk SM, Kelly AJ, MacNeil A, Goldsmith CS, Metcalfe MG, et al. A new phlebovirus associated with severe febrile illness in Missouri. N Engl J Med [Internet] 2012;367(9):834–41. Available from: http://www.nejm.org/doi/abs/10.1056/NEJMoa1203378.

Fill M, Compton M, McDonald E, Moncayo A, Dunn J, Schaffner W, et al. Novel clinical and pathologic finding in a heartland virus-associated death. Infect Deseases Soc Am. 2017;4(64):510–2.

Westover JB, Rigas JD, Van Wettere AJ, Li R, Hickerson BT, Jung KH, et al. Heartland virus infection in hamsters deficient in type I interferon signaling: protracted disease course ameliorated by favipiravir. Virology [Internet] 2017;511(August):175–83. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virol.2017.08.004.

Savage HM, Godsey MS, Panella NA, Burkhalter KL, Ashley DC, Lash RR, et al. Surveillance for heartland virus (bunyaviridae: phlebovirus) in Missouri during 2013: first detection of virus in adults of Amblyomma americanum (Acari: Ixodidae). J Med Entomol. 2016;53(3):607–12.

Molina K, Montoya C, Díaz FJ, Rodas JD. Enfermedades virales transmitidas por garrapatas. Iatreia. 2018;31(1):36–50.

Miranda J, Mattar S, Gonzalez M, Hoyos-López R, Aleman A, Aponte J. First report of Culex flavivirus infection from Culex coronator (Diptera: Culicidae), Colombia. Virol J. 2019;16(1):1–6.

M. Bbattesti D, Arzua M, Bechara GH. Carrapatos de importancia Medico Veterinaria da Regiao Neotropical: um guia ilustrado para identificac, ao de especies. Sao Paulo; 2006.

Stephen DW, Stephen WH, Barry JB. Estimation of infection rates in population organisms using pools of variable size. Am J Epideniology. 1980;112(1):124–8.

Sánchez-Seco MP, Echevarría JM, Hernández L, Estévez D, Navarro-Marí JM, Tenorio A. Detection and identification of Toscana and other phleboviruses by RT-nested-PCR assays with degenerated primers. J Med Virol. 2003;71(1):140–9.

Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K. MEGA X: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol Biol Evol. 2018;35:1547–9.

Li CX, Shi M, Tian JH, Lin XD, Kang YJ, Chen LJ, et al. Unprecedented genomic diversity of RNA viruses in arthropods reveals the ancestry of negative-sense RNA viruses. Elife. 2015;2015(4):1–26.

Souza WM, Acrani GO, Carrasco A, Fumagalli MJ, Romeiro MF, Modha S, et al. Identification of novel viruses in the families Flaviviridae (jigmenvirus), Chuviridae, and Bunyaviridae (phlebpvirus-like) in the ticks south Brazil. Int Bioinforma Work Virus Evol Mol Epidemiol. 2018;4(april):4974608.

Sameroff S, Tokarz R, Charles RA, Jain K, Oleynik A, Che X, et al. Viral Diversity of Tick Species Parasitizing Cattle and Dogs in Trinidad and Tobago. Sci Rep [Internet]. 2019;1–10. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-46914-1.

Lambert AJ, Lanciotti RS. Consensus amplification and novel multiplex sequencing method for s segment species identification of 47 viruses of the orthobunyavirus, phlebovirus, and nairovirus genera of the family bunyaviridae. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47(8):2398–404.

Klimentov AS, Butenko AM, Khutoretskaya N V., Shustova EY, Larichev VF, Isaeva O V., et al. Development of pan-phlebovirus RT-PCR assay. J Virol Methods [Internet] 2016;232:29–32. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jviromet.2016.02.009.

Acknowledgements

To University of Cordoba, Vice-Rectorate of Investigation, Sustainability group program, -CIUC- 2017-2018. And to Nicholas Komar. CDC, Arbovirus Diseases Branch, Fort Collins, CO, USA.

Funding

This study was supported by the University of Cordoba.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YL, JM and SM conceived and designed the experiments; YL, MG and JM collected, classified ticks and performed the experiments; YL, JM, SM and MG analyzed the data, wrote and revised the manuscript; JR sequenced the PCR amplicons and assisted with writing the final report. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

López, Y., Miranda, J., Mattar, S. et al. First report of Lihan Tick virus (Phlebovirus, Phenuiviridae) in ticks, Colombia. Virol J 17, 63 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-020-01327-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-020-01327-9