Abstract

Background

In Sub-Saharan Africa where HIV disproportionately affects women, heterosexual male sex workers (HMSW) and their female clients are at risk of acquiring or transmitting HIV and other STIs. However, few studies have described HIV and STI risk among HMSW. We aimed to assess and compare recent HIV and syphilis screening practices among HMSW and female sex workers (FSW) in Uganda.

Methods

Between August and December 2019, we conducted a cross-sectional study among 100 HMSW and 240 female sex workers (FSW). Participants were enrolled through snowball sampling, and an interviewer-administered questionnaire used to collect data on HIV and syphilis testing in the prior 12 and 6 months respectively. Integrated change model constructs were used to assess intentions, attitudes, social influences, norms and self-efficacy of 3-monthly Syphilis and 6-monthly HIV testing. Predictors of HIV and syphilis recent testing behaviors were estimated using negative binomial regression.

Results

We enrolled 340 sex workers of whom 100 (29%) were HMSW. The median age was 27 years [interquartile range (IQR) 25–30] for HMSW and 26 years [IQR], (23–29) for FSW. The median duration of sex work was 36 and 30 months for HMSW and FSW, respectively. HMSW were significantly less likely than FSW to have tested for HIV in the prior 12 months (50% vs. 86%; p = 0.001). For MSW, non-testing for HIV was associated with higher education [adjusted prevalence ratio (aPR) 1.66; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.09–2.50], poor intention to seek HIV testing (aPR 1.64; 95% CI 1.35–2.04), perception that 6-monthly HIV testing was not normative (aPR 1.33; 95% CI 1.09–1.67) and low self-efficacy (aPR 1.41; 95% CI 1.12–1.79). Not testing for syphilis was associated with low intention to seek testing (aPR 3.13; 95% CI 2.13–4.55), low self-efficacy (aPR 2.56; 95% CI 1.35–4.76), negative testing attitudes (aPR 2.33; 95% CI 1.64–3.33), and perception that regular testing was not normative (aPR 1.59; 95% CI 1.14–2.22).

Conclusions

Non-testing for HIV and syphilis was common among HMSW relative to FSW. Future studies should evaluate strategies to increase testing uptake for this neglected sub-population of sex workers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

There is global recognition that sex work is a key driver of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STI) in the general population [1,2,3,4]. Sex workers are female, male and transgender adults and young people who receive money or goods in exchange for sexual services [5]. While most of the evidence relates to female sex workers (FSW) [3, 4], male sex workers (MSW) are increasingly being recognized as a key population contributing to the global burden of HIV and STI [5,6,7]. Little is known about the risk of HIV acquisition among heterosexual male sex workers (HMSW) but overall, the risk in 2018 for sex workers was 21 times higher than adults aged 15–49 years, and 22 times more likely among gay men and other men who have sex with men than all adult men [6]. HIV prevalence estimates among MSW and female sex workers (FSW) are comparable. Research has found a high HIV prevalence among MSW: 5–31% in North America [7,8,9], 11.4–23% in South America [10, 11], and 14.5–43.6% in India [12,13,14]. The HIV burden among MSW is high in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), with an HIV prevalence of 26.3% and 50% in Kenya and Cote d’Ivoire, respectively [15, 16]. This is comparable to HIV prevalence observed among FSW (36.9%) in this setting [3], and globally (11.8–30.7%) [3]. However, most of these studies focus on MSW whose clients are men and FSW. Of the 800,000 new HIV infections that occurred in Eastern and Southern Africa in 2018, 25% were contributed by MSW,FSW and other key populations [17]. Sex workers are a bridge population; up to 15% of HIV infections in the general population are attributed to sex work [4].

Limited data are available on HMSW, perhaps because HMSW are usually less visible than FSW [18] and the assumption that sex work by heterosexual men constitutes a small proportion of male commercial sex [19, 20]. Additionally, risk of HIV acquisition through insertive penile-vaginal intercourse is lower than that for insertive or receptive anal intercourse among HMSW who have sex with women [21]. However, in SSA where HIV disproportionately affects women, heterosexual MSW and their female clients are at risk of either acquiring or transmitting HIV [22]. Inconsistent condom use, anal sex, lack of access to healthcare services and restrictive policies act in synergy to increase risk of HIV and STI among MSW. Further, STI co-infection increases HIV acquisition and transmission risk [23, 24]. STI like syphilis, chlamydia, trichomoniasis and gonorrhoeae are curable if detected and treated [1, 25]. Effective STI control among key populations is associated with a decline in STI incidence in the general population, and syphilis seroprevalence among FSW is an important proxy indicator of progress in STI control [25]. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends STI screening for sex workers every 3 months and HIV testing every 6–12 months [26, 27]. Uptake of regular STI and HIV screening services is an important entry point for antiretroviral treatment (ART) and prevention services (oral pre-exposure prophylaxis and voluntary medical male circumcision) [2, 26].

The hidden HMSW sub-population in Uganda is not well described. Anecdotal evidence (field reports and newspaper articles) suggests the existence of HMSW [28]. In northern Uganda, a community leader identified HMSW who target wealthy women as a key challenge to HIV epidemic control [28]. However, no published data are available on STI and HIV testing practices among HMSW in Uganda. Despite paucity of data on STI testing practices, up to 86% of FSW in Uganda report taking an HIV test in the prior 12 months [29, 30]. Our study aimed to assess and compare recent HIV and syphilis screening practices among HMSW, relative to FSW, in selected urban centers in Uganda.

Methods

Study design and setting

Between August and December 2019, we conducted a cross-sectional survey of 100 HMSW and 240 FSW in Kampala, the capital city of Uganda, and Mbarara municipality in Western Uganda (combined population 1702,274) to describe recent HIV and syphilis screening practices. Study participants included heterosexual men and women ≥ 17 years engaged in sex work according to self-report of selling sex for goods or money for at least 6 months. A two-stage sampling design was used to recruit study participants.

Population and procedures

Before recruiting respondents, we conducted a mapping exercise to gain an understanding of typologies, hot spots, network connections and territorial management in Kampala City and Mbarara Municipality as previously reported [30]. We observed from the mapping exercise that forms and strategies for male sex work included brokers, online advertising, social media and recreational venues. In contrast, FSW sold sex on the street and in lodges, bars/clubs and brothels (mainly in Kampala). We first identified three HMSW through key informants (FSW, escort service manager and bar/club maids). They were given information about study aims and recruitment of HMSW and provided with two to three paper coupons to recruit other HMSW.

Sex work hot spots constituted the primary sampling units (PSUs) for FSW. Using the different typologies, we established a sampling strategy for each study site. In Mbarara we randomly selected 12 PSUs consisting mainly of streets, lodges and bars/clubs, whereas in Kampala we randomly selected 20 PSUs consisting of streets, lodges, clubs/bars and brothels. Between 6 and 11 participants were enrolled from each PSU at each study site. Sampling began with two FSW at each PSU, who were identified through key informants (managers, club/bar maids and procurers). They were provided information about the study and given three paper coupons to distribute to potential study respondents in their networks. No incentives were given for coupon distribution. For both HMSW and FSW, the coupon contained an identification number, contact information of the research team and duration of the survey in the study site. FSW and HMSW who presented a coupon after verification, and met the eligibility criteria, were consented to participate in the study and completed an interviewer-administered questionnaire. After the interview, each enrollee was given two coupons to recruit more two potential respondents. Face-to-face interviews were conducted by the same interviewer at each site in order to minimize multiple presentation.

Before the interview, respondents were asked about prior or current use of ART. Respondents who were taking ART or knew their HIV status were excluded from the study. All study respondents received information about STI and HIV screening. The study was approved by the Higher Degrees Research and Ethics Committee, School of Public Health, Makerere University and the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (HS 2403). All respondents provided written informed consent in their language of preference.

Study variables

The primary outcome variable was recent syphilis (≤ 6 months) and HIV (≤ 12 month) testing. Respondents were asked if they had ever taken a serological syphilis and HIV test (Yes = 1, No = 2) and the number of times they had tested in the past 12 months. A 65-item questionnaire validated among FSW in Benin [31] was used to obtain data on the primary outcome and the major explanatory variables–intention (INT), attitude (ATT), self-efficacy (SE), descriptive norm (MN) and social influences (SI)–which were psychosocial constructs derived from Integrated Change Model [32]. The Integrated Change Model is used to explain motivational and behavioral change. It states that personal overt and covert behaviors are determined by individual motivation or intention to carry out HIV or syphilis testing [32], and that motivation is determined by attitudes, social influences and self-efficacy. We used integrated change model constructs to derive the psychosocial variables, i.e., intentions, attitudes, social influences, norms and self-efficacy of 3-monthly and 6-monthly HIV testing.

Intention

Intention in this study was defined as readiness to take a syphilis serological test (SYP_INT) in the next 3 months and an HIV (HIV_INT) test in the next 6 months by asking respondents three items for each infection, e.g., “Are you going to be screened for syphilis in the next 3 months”? Answers on a 6-point Likert scale ranged from 1 =’Strongly disagree’ to 6 = ‘Strongly agree’.

Attitude

Attitudes towards 3-monthly syphilis testing (SYP_ATT) were assessed through three items by asking respondents to what extent they agreed with statements such as, “For you getting tested for syphilis every 3 months, would reduce your risk of contracting HIV”. Answer options on a 6-point Likert scale ranged from 1 = ‘Strongly disagree’ to 6 = ‘Strongly agree’. Attitudes towards 6-monthly HIV testing (HIV_ATT) were assessed by asking respondents five items about the benefits and disadvantages of being tested for HIV every 6 months.

Descriptive norms

Descriptive norms regarding 3-monthly syphilis testing (SYP_MN) were assessed by asking respondents three questions about whether FSW or HMSW thought it was their moral obligation to test, and how often they thought their peers were testing for syphilis every 3 months. Respondents were asked to what extent they agreed with statements like “Being tested for syphilis is a normal routine that many FSW or HMSW practice?” Answers on a 6-point Likert scale ranged from 1 = ‘Strongly disagree’ to 6 = ‘Strongly agree’. Three items on the same scale were used to assess descriptive norms to 6-monthly HIV testing (HIV_MN) (e.g. “Based on what you know about your fellow FSW or HMSW and the practice of HIV testing, how many of them are being tested every 6 months?” Answering options ranged from 1 = ‘None’ to 6 = ‘All’.

Self-efficacy

Self-efficacy for 6-monthly HIV testing (HIV_SE) was assessed by seven questions about their perceived level of confidence and ease of seeking 6-monthly HIV testing. Items included a range of barriers including stigma, discrimination, fear of positive results, privacy and confidentiality. Questions included, “Do you feel able to go for an HIV test every 6 months, even if you are afraid of receiving a positive result?” Answering options on a 6-point Likert scale ranged from 1 = ‘Strongly disagree’ to 6 = ‘Strongly agree’. Self-efficacy for 3-monthly syphilis testing (SYP_SE) was assessed by one statement of whether they feel able to go for a serological syphilis test every 3 months.

Social influence

Social norms regarding 6-monthly HIV testing (HIV_SI) were assessed on a 6-point scale (1 = ‘Disapprove strongly’ to 6 = ‘Approve strongly’) by asking respondents two questions on whether referent others (fellow FSW or HMSW and regular partners/clients) approved or expected them to test for HIV every 6 months. We also obtained socio-demographic data on education, marital status and dependents.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were performed using Stata version 12.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). We used Cronbach’s alpha to evaluate the reliability of items in the questionnaire that were used to assess the major explanatory variables [33]. We computed a scale dimension for each component (SYP_INT, HIV_INT, SYP_ATT, HIV_ATT, SYP_MN, HIV_MN, and HIV_SE) by summing up Likert scores of individual items. The item for social influence (HIV_SI) had a non-reliable scale and was excluded from further analysis. Ordinal data were descriptively summarized using the scale median. Respondents were considered to score high on a component if their total score on the scale was above the scale median, while those with scores below the scale median were considered to score low on a component. Likert scale scores of 1–4 were considered low and scores of 5–6 were high for individual question item. Frequency distributions and proportions were used to describe demographic characteristics, condom use and syphilis and HIV testing behaviors of MSW and FSW. Pearson’s Chi square (χ2) tests were used to examine differences between major explanatory variables and sex. Student t test was used to ascertain if FSW and HMSW differed with regard to age, duration in sex work, and number of children or dependents. We evaluated predictors of self-reported frequency of recent HIV and syphilis testing (count data) using negative binomial regression (for overdispersed count data). We used a likelihood ratio test of alpha = 0 (dispersion parameter) to assess model fit and found no evidence of over-dispersion. Crude and adjusted prevalence ratios (PR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were estimated. We considered two-sided p-values of 0.05 or less statistically significant.

Results

Population Characteristics

A total of 340 SW took part in the study, of whom 100 (29.4%) were HMSW. The median age was 27 years [interquartile range (IQR) 25–30] for HMSW and 26 years [IQR], (23–29) for FSW (Table 1). The median duration of sex work was 36 and 30 months for MSW and FSW, respectively. Relative to FSW, most HMSW (89%) had obtained secondary or high education. A higher proportion of FSW (82%) reported having children compared to 64% of HMSW. Most HMSW (70%) had never married and only 11% engaged in full time sex work. They preferred female clientele aged 35 years or greater, whom they solicited through procurers, dating sites, social media and recreational venues. By contrast, FSW solicited clients on the street and in lodges, clubs, bars and brothels. Most HMSW (61%) serviced one to two clients per week compared with 92% of FSW who had five or more clients per week. Condom use at last sex was reported by only 16% of HMSW compared with 66% of FSW (Table 1). Similarly, consistent condom use was reported by only 10% of HMSW compared with 63% of FSW.

Construct reliability

The degree of internal consistency among question items was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha. The Cronbach’s α coefficients for SYP_INT, HIV_INT, SYP_ATT, HIV_ATT, SYP_MN, HIV_MN, HIV_SE and HIV_SI were 0.96, 0.95, 0.7, 0.85, 0.7, 0.78, 0.89 and 0.39, respectively.

Syphilis and HIV testing

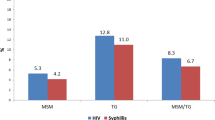

Compared to FSW (62.5%), self-report of ever testing for syphilis among HMSW was low (32%), as was testing in the prior 6 months (6% vs. 19%) (Table 2). Reasons cited by HMSW for not testing—fear (33%), not feeling sick (30%) and not beneficial (20%)–differed from FSW, for whom not being aware (40%), never thought about it (35%) and have no signs of illness (20%) influenced non-testing behaviors. Similarly, preferences for syphilis testing venues differed by sex, with 78% of HMSW preferring private clinics while FSW tested at public health clinics (49%), private clinics (35%) or during outreach campaigns (10%). Self-reported HIV testing in the prior 12 months was low among HMSW compared to FSW (50% vs 86%), as was ever testing for HIV (80% vs. 96%). In contrast to syphilis testing, HMSW preferences for HIV testing were diverse: public clinics (34%), private clinics (29%), outreach campaigns (23%), and self-testing (8%). FSW preferred to test at public (53%) or private clinics (45%).

Psychosocial influences of regular syphilis and HIV testing

We found that compared to FSW, HMSW had low intentions or attitudes towards 3-monthly Syphilis or 6-montthly HIV testing (Table 3). Relative to FSW, a low proportion of HMSW had intentions to test for syphilis in the next 3 months (19% vs. 63%), test for HIV in the next 6 months (24% vs. 66%), believe in the benefits of regular testing for syphilis (29% vs. 65%) or HIV (11% vs. 75%), have self-efficacy to seek regular syphilis (40% vs. 84%) or HIV testing (38% vs. 60%) or perceive that regular syphilis (33% vs. 68%) or HIV testing (19% vs. 70%) was normative for SW (Table 4).

Associations with syphilis and HIV testing

Next, we examined factors associated with testing for syphilis and HIV in the prior 6 and 12 months, respectively. In multivariate analysis after adjustment for age, level of education, marital status, study site, attitudes to testing and condom use practices, attainment of higher education [adjusted prevalence ratio (aPR) 1.66; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.09–2.50; p = 0.02], poor intention to seek HIV testing (aPR 1.64; 95% CI 1.35–2.04; p < 0.001), perception that 6-monthly HIV testing was not common (aPR 1.33; 95% CI 1.09–1.67; p = 0.007) and poor self-efficacy (aPR 1.41; 95% CI 1.12–1.79; p = 0.005) were associated with HIV non-testing (Table 5).

In the multivariable model adjusting for age, level of education, marital status, and study site, low intention to seek syphilis testing (aPR 3.13; 95% CI 2.13–4.55; p < 0.001), negative testing attitudes (aPR 2.33; 95% CI 1.64–3.33; p = 0.004), perception that regular testing was not normative (aPR 1.59; 95% CI 1.14–2.22; p < 0.001), and low self-efficacy (aPR 2.56; 95% CI 1.35–4.76; p = 0.007) were associated with syphilis non-testing (Table 6).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate HIV and syphilis testing among HMSW in Uganda. In this cross-sectional study, the majority of HMSW had attained higher education but had lower testing rates for syphilis and HIV and less condom use than FSW. HMSW preferred testing in private health facilities whereas FSW preferred public health facilities. Among HMSW, HIV non-testing was associated with higher education, poor self-efficacy, and poor testing norms and perceptions. Syphilis non-testing was associated with negative testing attitudes, low self-efficacy and low intention to seek testing.

We found that 50% of HMSW reported not testing for HIV in the past 12 months. Non-testing for HIV was common in prior studies from Asia and Africa [34,35,36]. A study of HMSW in Singapore found that only 27% had tested for HIV or STIs in the past 6 months [34]. In China, only 48.6% of MSW who have sex with men had tested for HIV [35, 36]. In Kenya, a study found low prevalence (26%) of recent HIV testing among MSW [37]. Work done in the Netherlands also found that majority of HMSW (63%) reported no recent history of HIV or STI testing compared with 32% of FSW [38]. However, most of these studies focused on MSW whose clients were male [35,36,37]. The higher HIV testing rate (86%) we found could be due to targeted HIV testing programs for FSW in Uganda [39,40,41]. Similar findings were reported from a recent study in Uganda where 86% of FSW reported taking an HIV test in the prior 12 months [29]. HMSW are hidden key sub-population largely invisible to HIV programs [38]. Entrenched social stigma, healthcare discrimination and criminalization of sex work limit access to, and uptake of, testing services [42, 43]. Additionally, HMSW may not identify as sex workers nor perceive themselves to be at risk of HIV and other STIs [20, 38, 44]. These factors may account for the low testing norms, low self-efficacy and poor uptake of HIV testing we observed. Although higher levels of education have been associated with better health seeking behaviours [45, 46], better educated HMSW in our study were less likely to test for HIV than FSW perhaps because of lack of HIV services targeted to HMSW.

We found low syphilis testing rates among HMSW and FSW which is consistent with prior studies of sex workers in Uganda, and elsewhere, that reported low syphilis testing behaviors [3, 20, 30, 47, 48]. Syphilis is a less stigmatized disease than HIV in Uganda [49]. One study found that the perception of syphilis as a genetic (inherited) disease was a barrier to testing among men [50]. Our finding that testing rates were lower for syphilis than HIV could be explained by social and individual perceptions of these diseases. Unlike HIV, syphilis is not perceived as a significant threat to personal health in this setting [51]. Additionally, FSW are more likely to receive information about syphilis testing during moonlight HIV counselling and testing (HCT) outreach campaigns and antenatal care; dual syphilis and HIV testing is standard of care in antenatal clinics in Uganda [39, 52]. Testing attitudes and intentions are influenced by knowledge and personal evaluation of the merits and demerits of regular syphilis testing [53, 54]. Lack of knowledge, stigma and poor attitudes of health workers are barriers to utilization of STI services [55]. The low intentions, negative attitudes and poor testing norms we observed among HMSW could suggest lack of comprehensive knowledge of syphilis, the benefits of regular testing, and barriers to testing including stigma, discrimination and perceived attitudes of providers [44]. These findings are consistent with studies showing that psychosocial factors including intentions, attitudes, norms and self-efficacy influence STI and HIV testing behaviors [56]. They may also result from policy and programmatic focus on HIV and frequent stock outs of syphilis test kits in Uganda. Compared to HIV, where national testing guidelines [57] target the general population, syphilis guidelines focus on pregnant women [39]. These policy choices could limit HMSW access to regular syphilis testing unlike FSW who are targeted during testing campaigns or antenatal care [39, 41]. Scaling up point-of-care (POC) testing for HIV and syphilis increases uptake of testing services by sex workers [58] and enables early treatment of both diseases [59, 60].

The strengths of our study include being the first study (to our knowledge) to evaluate HIV and syphilis testing among HMSW in Uganda and use of the integrated change model to guide the design and analysis of major explanatory variables with reliable item statements (Cronbach’s α ≥ 0.7). Our study has limitations. The study design was cross-sectional, and our findings do not account for time trends in testing behaviors. Participants recruited from two large urban centers may not be representative of all HMSW in Uganda. Social desirability and recall bias may have influenced self-report of HIV and syphilis testing behaviors. Nevertheless, studies with larger sample sizes and longer duration of follow up have reported similar findings.

In conclusion, non-testing for HIV and syphilis was common among HMSW in Uganda. These data inform HIV and STI programming for sex workers which should scale-up dual HIV and syphilis POC testing for HMSW. Future studies should evaluate strategies to increase testing uptake in this neglected sub-population of sex workers.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request. The questionnaire is included as supplementary information.

Abbreviations

- FSW:

-

Female sex workers

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- MSW:

-

Male sex workers

- HMSW:

-

Heterosexual male sex workers

- PSU:

-

Primary sampling unit

- STI:

-

Sexually transmitted infection

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

World Health Organization. Sexually transmitted infections: implementing the global STI strategy. Geneva.: World Health Organization; 2017.

World Health Organization: Global health sector strategy on sexually transmitted infections 2016–2021: toward ending STIs. 2016.

Baral S, Beyrer C, Muessig K, Poteat T, Wirtz AL, Decker MR, Sherman SG, Kerrigan D. Burden of HIV among female sex workers in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12(7):538–49.

Prüss-Ustün A, Wolf J, Driscoll T, Degenhardt L, Neira M, Calleja JMG. HIV due to female sex work: regional and global estimates. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(5):e63476.

UNAIDS. UNAIDS guidance note on HIV and sex work. Geneva: UNAIDS Geneva; 2009.

UNAIDS: UNAIDS DATA 2019. In. https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2019/2019-UNAIDS-data; 2018.

Bacon O, Lum P, Hahn J, Evans J, Davidson P, Moss A, Page-Shafer K. Commercial sex work and risk of HIV infection among young drug-injecting men who have sex with men in San Francisco. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33(4):228–34.

Minichiello V, Scott J, Callander D. New pleasures and old dangers: reinventing male sex work. J Sex Res. 2013;50(3–4):263–75.

Reisner SL, Mimiaga MJ, Mayer KH, Tinsley JP, Safren SA. Tricks of the trade: sexual health behaviors, the context of HIV risk, and potential prevention intervention strategies for male sex workers. J LGBT Health Res. 2008;4(4):195–209.

dos Ramos Farías MS, Garcia MN, Reynaga E, Romero M, Vaulet MLG, Fermepín MR, Toscano MF, Rey J, Marone R, Squiquera L. First report on sexually transmitted infections among trans (male to female transvestites, transsexuals, or transgender) and male sex workers in Argentina: high HIV, HPV, HBV, and syphilis prevalence. Int J Infect Dis. 2011;15(9):e635–40.

Tun W, de Mello M, Pinho A, Chinaglia M, Diaz J. Sexual risk behaviours and HIV seroprevalence among male sex workers who have sex with men and non-sex workers in Campinas, Brazil. Sex Transm Infect. 2008;84(6):455–7.

Brahmam GN, Kodavalla V, Rajkumar H, Rachakulla HK, Kallam S, Myakala SP, Paranjape RS, Gupte MD, Ramakrishnan L, Kohli A, et al. Sexual practices, HIV and sexually transmitted infections among self-identified men who have sex with men in four high HIV prevalence states of India. Aids. 2008;22(Suppl 5):S45–57. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.aids.0000343763.54831.15.

Narayanan P, Das A, Morineau G, Prabhakar P, Deshpande GR, Gangakhedkar R, Risbud A. An exploration of elevated HIV and STI risk among male sex workers from India. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:1059.

Bayer AM, Garvich M, Diaz DA, Sanchez H, Garcia PJ, Coates TJ. ‘Just getting by’: a cross-sectional study of male sex workers as a key population for HIV/STIs among men who have sex with men in Peru. Sex Transm Infect. 2014;90(3):223–9.

Muraguri N, Tun W, Okal J, Broz D, Raymond HF, Kellogg T, Dadabhai S, Mutua H, Sheehy M, Kuria D. Burden of HIV and sexual behavior among men who have sex with men and male sex workers in Nairobi, Kenya In 2012. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;68(1):91–6.

Vuylsteke B, Semde G, Sika L, Crucitti T, Traore VE, Buve A, Laga M. High prevalence of HIV and sexually transmitted infections among male sex workers in Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire: need for services tailored to their needs. Sex Transmit Infect. 2012;88(4):288–93.

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS: Fact sheet: World AIDS Day 2019—global HIV statistics. 2019.

Bayer AM, Garvich M, Diaz DA, Sanchez H, Garcia PJ, Coates TJ. When sex work becomes your everything: the complex linkages between economy and affection among male sex workers in peru. Am J Men’s Health. 2014;8(5):373–86.

Aggleton P. Men who sell sex: International perspectives on male prostitution and HIV/AIDS. Philadelphia: Temple University Press; 1999.

Baral SD, Friedman MR, Geibel S, Rebe K, Bozhinov B, Diouf D, Sabin K, Holland CE, Chan R, Cáceres CF. Male sex workers: practices, contexts, and vulnerabilities for HIV acquisition and transmission. Lancet. 2015;385(9964):260–73.

Patel P, Borkowf CB, Brooks JT, Lasry A, Lansky A, Mermin J. Estimating per-act HIV transmission risk: a systematic review. AIDS. 2014;28(10):1509.

Mannava P, Geibel S, King’ola N, Temmerman M, Luchters S. Male sex workers who sell sex to men also engage in anal intercourse with women: evidence from Mombasa, Kenya. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(1):e52547.

Freeman EE, Weiss HA, Glynn JR, Cross PL, Whitworth JA, Hayes RJ. Herpes simplex virus 2 infection increases HIV acquisition in men and women: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Aids. 2006;20(1):73–83.

Fleming DT, Wasserheit JN. From epidemiological synergy to public health policy and practice: the contribution of other sexually transmitted diseases to sexual transmission of HIV infection. Sex Transmit Infect. 1999;75(1):3–17.

WHO. Report on global sexually transmitted infection surveillance 2015. Geneva: WHO Geneva; 2015. p. 1.

World Health Organization. Prevention and treatment of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections for sex workers in low-and middle-income countries: recommendations for a public health approach. 2012.

World Health Organization. Policy brief: Consolidated guidelines on HIV prevention, diagnosis, treatment and care for key populations. Geneva.: World Health Organization; 2017.

Gulu alarmed by rising number of male sex workers [https://observer.ug/news/headlines/61707-gulu-alarmed-by-rising-number-of-male-sex-workers].

Pande G, Bulage L, Kabwama S, Nsubuga F, Kyambadde P, Mugerwa S, Musinguzi J, Ario AR. Preference and uptake of different community-based HIV testing service delivery models among female sex workers along Malaba-Kampala highway, Uganda, 2017. BMC Health Services Res. 2019;19(1):799.

Muhindo R, Castelnuovo B, Mujugira A, Parkes-Ratanshi R, Sewankambo NK, Kiguli J, Tumwesigye NM, Nakku-Joloba E. Psychosocial correlates of regular syphilis and HIV screening practices among female sex workers in Uganda: a cross-sectional survey. AIDS Res Therapy. 2019;16(1):28.

Batona G, Gagnon M-P, Simonyan DA, Guedou FA, Alary M. Understanding the intention to undergo regular HIV testing among female sex workers in Benin: a key issue for entry into HIV care. JAIDS J Acquir Immun Defic Syndr. 2015;68:S206–12.

De Vries H. An integrated approach for understanding health behavior; the I-change model as an example. Psychol Behav Sci Int J. 2017;2(2):10.19080.

Santos JRA. Cronbach’s alpha: a tool for assessing the reliability of scales. J Extens. 1999;37(2):1–5.

Lim RBT, Tham DKT, Cheung ON, Tai BC, Chan R, Wong ML. What are the factors associated with human immunodeficiency virus/sexually transmitted infection screening behaviour among heterosexual men patronising entertainment establishments who engaged in casual or paid sex?–Results from a cross-sectional survey in an Asian urban setting. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16(1):763.

Jin H, Friedman MR, Lim SH, Guadamuz TE, Wei C. Suboptimal HIV testing uptake among men who engage in commercial sex work with men in Asia. LGBT Health. 2016;3(6):465–71.

Cai R, Cai W, Zhao J, Chen L, Yang Z, Tan W, Zhang C, Gan Y, Zhang Y, Tan J. Determinants of recent HIV testing among male sex workers and other men who have sex with men in Shenzhen, China: a cross-sectional study. Sexual Health. 2015;12(6):565–7.

Shangani S, Naanyu V, Mwangi A, Vermandere H, Mereish E, Obala A, Vanden Broeck D, Sidle J, Operario D. Factors associated with HIV testing among men who have sex with men in Western Kenya: a cross-sectional study. Int J STD AIDS. 2017;28(2):179–87.

Verhaegh-Haasnoot A, Dukers-Muijrers NH, Hoebe CJ. High burden of STI and HIV in male sex workers working as internet escorts for men in an observational study: a hidden key population compared with female sex workers and other men who have sex with men. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15(1):291.

Ministry of Health: Consolidated Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of HIV and AIDS in Uganda. 2018.

Wanyenze RK, Musinguzi G, Kiguli J, Nuwaha F, Mujisha G, Musinguzi J, Arinaitwe J, Matovu JK. “When they know that you are a sex worker, you will be the last person to be treated”: perceptions and experiences of female sex workers in accessing HIV services in Uganda. BMC Int Health Human Rights. 2017;17(1):11.

Uganda AIDS Commission: National HIV and AIDS Strategic Plan 2015/2016–2019/2020. 2015.

Kim HY, Grosso A, Ky-Zerbo O, Lougue M, Stahlman S, Samadoulougou C, Ouedraogo G, Kouanda S, Liestman B, Baral S. Stigma as a barrier to health care utilization among female sex workers and men who have sex with men in Burkina Faso. Ann Epidemiol. 2018;28(1):13–9.

Davis A, Meyerson BE, Aghaulor B, Brown K, Watson A, Muessig KE, Yang L, Tucker JD. Barriers to health service access among female migrant Ugandan sex workers in Guangzhou, China. Int J Equity Health. 2016;15(1):170.

Boyce P, Isaacs G, Duncan C, Goagoseb N, Harper E, Kanengoni A, Kata G, Macklean K, Mathenge J, Massilela N. An exploratory study of the social contexts, practices and risks of men who sell sex in Southern and Eastern Africa. African Sex Worker Alliance. 2011.

Cutler DM, Lleras-Muney A. Education and health: insights from international comparisons. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research; 2012.

Thorpe KE, Joski P. Association of social service spending, environmental quality, and health behaviors on health outcomes. Popul Health Manage. 2018;21(4):291–5.

Hladik W, Baughman AL, Serwadda D, Tappero JW, Kwezi R, Nakato ND, Barker J. Burden and characteristics of HIV infection among female sex workers in Kampala, Uganda–a respondent-driven sampling survey. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):565.

Baral S, Sifakis F, Cleghorn F, Beyrer C. Elevated risk for HIV infection among men who have sex with men in low-and middle-income countries 2000–2006: a systematic review. PLoS Med. 2007;4(12):e339.

Atukunda EC, Mugyenyi GR, Oloro J, Hughes S. Tackling sexually transmitted infection burden in Ugandan communities living in the United Kingdom: a qualitative analysis of the socio-cultural interpretation of disease and condom use. Afr Health Sci. 2015;15(3):878–87.

Nakku-Joloba E, Kiguli J, Kayemba CN, Twimukye A, Mbazira JK, Parkes-Ratanshi R, Birungi M, Kyenkya J, Byamugisha J, Gaydos C. Perspectives on male partner notification and treatment for syphilis among antenatal women and their partners in Kampala and Wakiso districts, Uganda. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19(1):124.

Rowe JA. Revolution in Buganda 1856–1900. Part one: the reign of Kabaka Mukabya Mutesa 1856–1884. 1968.

Ministry of Health: National HIV testing services policy and implementation guidelines Uganda. 2016.

Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991;50(2):179–211.

De Vries H. An integrated approach for understanding health behavior; the I-change model as an example. Psychol Behav Sci Int J. 2017;2(2):555–85.

Chersich MF, Luchters S, Ntaganira I, Gerbase A, Lo YR, Scorgie F, Steen R. Priority interventions to reduce HIV transmission in sex work settings in sub-Saharan Africa and delivery of these services. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16(1):17980.

Nnko S, Kuringe E, Nyato D, Drake M, Casalini C, Shao A, Komba A, Baral S, Wambura M, Changalucha J. Determinants of access to HIV testing and counselling services among female sex workers in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):15.

Uganda Ministry of Health. National HIV testing services policy and implementation guidelines Uganda. 2016.

Mitchell KM, Cox AP, Mabey D, Tucker JD, Peeling RW, Vickerman P. The impact of syphilis screening among female sex workers in China: a modelling study. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(1):e55622.

Ouedraogo HG, Meda IB, Zongo I, Ky-Zerbo O, Grosso A, Samadoulougou BC, Tarnagda G, Cisse K, Sondo A, Sawadogo N, et al. Syphilis among female sex workers: results of point-of-care screening during a cross-sectional behavioral survey in Burkina Faso, West Africa. Int J Microbiol. 2018;2018:4790560.

Black V, Williams BG, Maseko V, Radebe F, Rees HV, Lewis DA. Field evaluation of Standard Diagnostics’ Bioline HIV/Syphilis Duo test among female sex workers in Johannesburg, South Africa. Sex Transm Infect. 2016;92(7):495–8.

Acknowledgements

Richard Muhindo is a NURTURE fellow funded through grant D43TW010132 from the National Institutes of Health. Special thanks to NURTURE program, mentors and the secretariat. He is also a PhD scholar under the Johnson & Johnson Corporate Citizenship Trust grant at Ugandan Academy of Health Innovation and Impact, Infectious Diseases Institute Uganda. Special thanks to the Infectious Diseases Institute (IDI), PhD scholar Mentorship program and the IDI PhD scholar forum. The authors thank the Director of Public Health, Kampala Capital City Authority and Town Clerk, Mbarara municipality for administrative approval. We thank the participants for volunteering to participate in the study. Finally, we thank Collins Twesigye, Jennifer Bako, Alfred Okuonzi and Michael Muhoozi who worked as research assistants.

Funding

This study was supported through grant number D43TW010132 supported by Office Of The Director, National Institutes Of Health (OD), National Institute Of Dental & Craniofacial Research (NIDCR), National Institute Of Neurological Disorders And Stroke (NINDS), National Heart, Lung, And Blood Institute (NHLBI), Fogarty International Center (FIC), National Institute On Minority Health And Health Disparities (NIMHD) and a grant from the Ugandan Academy of Health Innovation and Impact. The Ugandan Academy is initially funded by Janssen, the Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson as part of its commitment to global public health through collaboration with the Johnson & Johnson Corporate Citizenship Trust. AM was supported through grants K43TW010695 and R34MH121084 from the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RM conceived the research idea, participated in the design of the study including coordination of data collection, and drafting of the manuscript. BC, RP, NK, JK, NM, AM, NKS and EN participated in refining the research idea and design including data collection tools. RM, EN and NM performed the statistical analyses. RM, BC, and AM wrote the first draft. All authors contributed to interpretation of the results and the writing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Higher Degrees, Research and Ethics Committee, School of Public Health, Makerere University and Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (HS 2403). All respondents provided written consent in English or their local language.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Muhindo, R., Mujugira, A., Castelnuovo, B. et al. HIV and syphilis testing behaviors among heterosexual male and female sex workers in Uganda. AIDS Res Ther 17, 48 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12981-020-00306-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12981-020-00306-y