Abstract

Background

Through universal “test and treat approach” (UTT) it is believed that HIV new infection and AIDS related death will be reduced at community level and through time HIV can be eliminated. With this assumption the UTT program was implemented since 2016. However, the effect of this program in terms of individual patient survival and treatment outcome was not assessed in relation to the pre-existing defer treatment approach.

Objective

To assess the effects of UTT program on HIV treatment outcomes and patient survival among a cohort of adult HIV infected patients taking antiretroviral treatment in Gurage zone health facilities.

Methods

Institution based retrospective cohort study was conducted in facilities providing HIV care and treatment. Eight years (2012–2019) HIV/AIDS treatment records were included in the study. Five hundred HIV/AIDS treatment records were randomly selected and reviewed. Data were abstracted using standardized checklist by trained health professionals; then it was cleaned, edited and entered by Epi info version 7 and analyzed by STATA. Cox model was built to estimate survival differences across different study variables.

Results

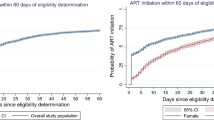

A total of 500 patients were followed for 1632.6 person-year (PY) of observation. The overall incidence density rate (IDR) of death in the cohort was 3 per-100-PY. It was significantly higher for differed treatment program, which is 3.8 per-100-PY compared to 2.4 per-100-PY in UTT program with a p value of 0.001. The relative risk of death among differed cases was 1.58 times higher than the UTT cases. The cumulative probability of survival at the end of 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th years was 98%, 90.2%, 89.2% and 88% respectively with difference between groups. The log rank test and Kaplan–Meier survival curve indicated patients enrolled in the UTT program survived longer than patients enrolled in the differed treatment program (log rank X2 test = 4.1, p value = 0.04). Age, residence, base line CD4 count, program of enrolment, development of new OIS and treatment failure were predicted mortality from HIV infection.

Conclusion

Mortality was significantly reduced after UTT. Therefore, intervention to further reduce deaths has to focus on early initiation of treatment and strengthening UTT programs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection remains the leading cause of morbidity and mortality throughout the world. Ethiopia is one of HIV hard hit countries with a prevalence of 1.1% [1, 2]. World Health Organization (WHO) developed the “universal test and treat” (UTT) program as strategy for HIV elimination in place of the previous “differed treatment” (CD4 based and WHO clinical staging approaches) program [3,4,5,6]. UTT is a program which commends all population at risk is screened for HIV infection and those diagnosed HIV positive receive early treatment regardless of their CD4 count and WHO clinical stage. Many countries including Ethiopia had adopted the ‘test and treat’ program [7,8,9].

Although, the health care systems has accepted the public health benefit of universal test and treat strategy for the prevention of new transmission, evidences on its impact on clinical outcome and patient survival are limited [3]. Although, WHO recommends the universal test and treat program, about 11% of low and middle income countries do not implemented it yet [10]. On the contrary, there are countries that have implemented the universal test and treat program before the WHO recommendation by their own initiative. As a result of clinical, public health and economic concerns different countries have been recommended ART initiation at different stages of the disease or at different levels of CD4 count [11, 12]. Thus, assuring the individual level benefit of the program in terms of treatment outcome and patient survival is very important to bring additional evidence helpful for scaling up program intervention.

Few studies conducted abroad in areas of treatment outcomes have reported different findings. Some model studies had shown that test and treat strategy as the effect of early initiation of treatment has impact on all epidemiological aspects of HIV/AIDS. The effects reported and predicted were particularly related with achieving higher survival time, development of resistance at higher rate, higher immune reconstitution syndrome rate and lower mortality. However, there is shortage of clinical research for clinical decisions [4,5,6, 8, 9].

A research in Canada has shown that test and treat strategy have associated with decreased morbidity, mortality and HIV transmission, and increases the life expectancy of people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) [13, 14]. Another study on early initiation of treatment has shown to reduce transmission to the HIV negative partner by 96% and reduces adverse health events by 41% for the person living with HIV [15, 16]. Furthermore, a research from South Africa indicated that, implementation of universal testing and treatment initiation for adults over 15 years old would subsequently decrease HIV prevalence by reducing rate of transmission [17].

Universal testing and treatment alone was associated with significant gain in life which is estimated 12.0 (11.3–12.2) months, In addition it results in 27.7% decrease in deaths from HIV and 1.6% reductions in adult HIV prevalence compared to the differed treatment program [18]. Recent two randomized studies showed that ART initiation immediately after HIV diagnosis irrespective of the CD4+ T cell count leads to a significant reduction of morbidity and mortality [15, 17,18,19,20,21]. It can also improve the treatment outcome of HIV infected patients by increasing uptake of the therapy and reducing lost to follow-up [20,21,22,23].

On the other hand possibility of poor ART adherence due to rapid ART initiation and shorter counseling time, pill burden due to other concurrent comorbidities; and presence of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) in patients with low CD4 level, especially in individuals with advanced disease raised concerns in the program [23,24,25,26]. On top of that, researches have reported that asymptomatic patients with higher CD4 cell counts has poor adherence to ART so that early initiation would results in loss to follow up [25]. Moreover, widespread use of antiretroviral treatment at a population and individual level may lead to development of drug resistance [26, 27].

Despite all associated concerns, the UTT program has been in practice since 2016 in Ethiopia. It is partly on implementation to reduce transmission of the disease at community level. However, its real effect on the treatment outcome and patient survival was not evaluated. Therefore, this study is aimed to assess the effect of the UTT program in treatment outcome and patient survival, by recruiting a cohort of ART users in the new (UTT) approach and the previous (differed treatment/CD4 based) programs in Ethiopia, Gurage zone. The evidence will be used as base line information for planners, implementers and aid organizations.

Methods and materials

Study design and settings

This institution based retrospective cohort study was conducted in health facilities of Gurage zone, Southern Ethiopia from May/2019 to June/2019 by using 8 year cohorts. The zone has 13 districts and 5 town administrations. There are 74 health centers, 6 hospitals and 4 private clinics. Of these 20 facilities provide HIV care and treatment in the area. There are clients initially enrolled in the differed treatment and the current UTT programs.

Study population and sampling technique

The source population was all adults (age 15+) with HIV enrolled to treatment program in all health facilities of Gurage zone. Sample size is calculated based on, sample size estimation for the assessment of survival time under the Cox proportional hazards model/log rank test by using the STATA Version 11.0 computer program considering the following assumptions: hazard ratio of 0.77 [20], 60% proportion of controls, 0.5 standard deviation of covariates of interest, with 5% marginal error and power of 80%. Finally by adding 10% for incompleteness, the sample size was 512. The sample was allocated proportionally for the five selected facilities and records were selected randomly.

Data collection procedure and data quality control

The sources of data for this study were Pre-ART register, the ART register and the patients’ ART follow up and medical charts. In those registers and follow up charts, clients’ socio demographic, clinical and laboratory information, treatments being provided, the follow up status of each client were recorded. Data was collected from client charts using a structured checklist for records review developed from the registers and follow up charts. Eight data collectors and six supervisors who are health professionals and working in ART clinics were recruited for data collection after getting training on the tool.

Study variables and data analysis

The outcome variable is time to death from enrolment to the cART program. The survival time is measured as the time period between date of enrolment and date of death, and it is dichotomized as death and censored. The censored cases include the alive patients, defaulters and transferred outs.

Data was cleaned, coded and entered into Epi-info version 7 and exported to STATA version 11, and then exploratory data analysis carried out to check assumptions. Kaplan–Meier survival curve together with log rank test was fitted to test for the presence of difference in survival time and incidence of death among patients enrolled in the UTT and differed treatment programs (UTT and differed). Incidence of death with respect to person time at risk was calculated. Finally, Cox-regression analysis was carried out to identify independent predictors of death in both groups. The forward stepwise regression method was applied and level of significance was used at p value less than 0.05. Model fitness checked by graphing residual plots with Cox-snell residual plot.

Results

A total of 500 randomly selected ART records (204 from the test and treat program and 296 from deferred treatment/CD4 based treatment program) were extracted with structured check list. Two third (67.2%) of the patients enrolled into the study were females and 280 (56%) were urban residents. Nearly half (52.8%) of the clients were married and one third (36.8%) of patients has no formal education (Table 1).

The mean age at time of diagnosis was 35 (SD = 9.3) years with no difference between the two programs. The median time from diagnosis to initiation of treatment was 0.7 (IQR = 0.2–1.1) year. The average weight of participants was 52.16 kg (SD = 11.2), patients in the UTT program have slightly higher weight (53 ± 12 kg) than patients in the differed program (51 ± 10 kg). The median CD4 count during initiation of ART was 198 (IQR: 125–302), it was higher among patients in the UTT program 257.5 (IQR: 129–560) than the differed treatment 182 (IQR: 110–234.5) (Table 1).

During initiation of ART 50.8% of the patients were in WHO clinical stage III and IV in both groups. Specifically on the UTT program, only 27.5% of patients were in WHO clinical stage III and IV, whereas in the deferred treatment program nearly 67% of patients were in WHO clinical stage III and IV. More than half (59.2%) of patients were enrolled in the differed treatment program. In differed program, 178 (60%) of cases were initiated ART treatment with both WHO clinical staging and CD4 count. Majority of patients were on first line treatment regimen in both cases (Table 1).

Survival status and treatment outcome

Five hundred patients were followed for different periods of time with a total of 1632.6 person-year of observation. During the follow up period, 48 patients died. Hence, the overall incidence density rate (IDR) of death in the cohort was 0.03 per person-year which is equal to 3 people per 100 peoples within 1 year of observation. It is significantly different for the two comparison groups. The incidence density rate was 0.038 per person year of observation in differed treatment groups whereas the incidence density rate was 0.024 per person year in universal treatment program with a p value of 0.001. The relative risk of death among differed cases was 1.58 times higher than the UTT cases.

The cumulative probability of survival at the end of 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th years of enrolment to treatment was 98%, 90.2%, 89.2% and 88% respectively with significant difference between the two groups. The log rank test and Kaplan–Meier survival curve indicated that a survival difference between the two groups is significant. However, the median survival time was undetermined. Because the largest observed analysis time was censored; the survivor function does not go to zero (Fig. 1). Patients enrolled in the UTT program survive longer than clients enrolled in the differed treatment program (log rank X2 test = 4.1, p value = 0.04) (Fig. 2).

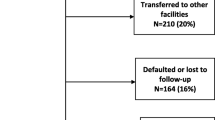

During the follow up period 48 (9.6%) patients died, 44 (8.8%) dropped out from treatment program, 90 (18%) transferred out, and the remaining 318 (63.6%) patients are on treatment follow up. Most deaths were recorded within the first few years of treatment initiation (Table 2).

Factors associated with mortality

Bivariate and multiple cox regression

In bivariate cox regression, age, sex, educational status, base line weight, base line CD4 count, program of enrolment, development of new OIS and treatment failure were associated with mortality. By using variables which have p value less than 0.25 in the bivariate analysis multiple cox regression was fitted with forward stepwise method. After controlling the effect of other variables age, residence, base line CD4 count, program of enrolment, development of new OIS and treatment failure significant predictors of survival time or mortality of HIV patients who are on ART treatment (Table 3).

After controlling the effect of other variables, patients living in rural setups were 2.42 (95% CI [1.5–3.8], p value < 0.001) times more likely to die than urban resident patients. The risk of death was 4.13 (95% CI [1.86–9.17], p value < 0.001) times higher for patients who were enrolled in the differed treatment (CD4 based) program than patients enrolled in the universal test and treat program. Likewise, patients who developed treatment failure were 3.8 (95% CI [1.8–8.4], p value < 0.001) times more likely to die than their counter parts. Similarly, the risk of death in patients who developed new OIS was 3.66 (95% CI [2.4–5.6], p value < 0.001) times higher than those who did not develop new OIS. In addition, the increment of base line CD4 count by one unit reduces the probability of death by 0.4%. On the other hand the likely hood of mortality was increased by 5% as age increased by a year (Table 3).

Discussion

This study assessed the effects of UTT program in comparison with the differed program on survival status and treatment outcomes of HIV infected patients initiated ART treatment in health facilities of Gurage zone. The incidence of death was significantly higher in the differed (CD4 based) program than the UTT program. It may be due to the fact that patients during the differed program commonly present with late WHO clinical stages or after developing serious opportunistic infection [2,3,4,5,6]. Similarly, the immune response depends on CD4 level, so that; patients in the differed program may not have good response to treatment [5].

Patients in the UTT survived for longer period of time than patients enrolled in the differed treatment program. As the universal test and treat program makes patients to get medical support in the early stages of infection the response to treatment will be obviously better [7,8,9]. Meanwhile, early treatment and prophylaxis prevents the development of fatal opportunistic infections. So that the survival of patients in the test and treat program is longer [2, 3]. Also previous studies reported that early presentation and medical care increases the survival of patients [14,15,16,17,18]. It has to be noted that patients who were enrolled under differed program were not followed until their CD4 count or WHO stage make them eligible to be enrolled for treatment. However patients on UTT program were enrolled for treatment soon after diagnosis, hence these time lapses between diagnosis and enrolment for treatment would have an impact on survival time differences.

The probability of survival at the end of 2 years of follow up is higher than the findings of previous studies conducted elsewhere [15, 17,18,19]. This is due to the effect of the universal test and treat program included in our study, which increases the survival of patients [16, 19]. On the other hand, the cumulative incidence of mortality was significantly higher among patients enrolled in differed treatment programs compared to patients enrolled in UTT program. This can be explained by increased risk of opportunistic infections, treatment failure and drug side effects which are more common in the differed treatment arm [15,16,17,18].

During the follow up period 48 (9.6%) patients died. Lower rate of death was observed in the UTT cohort. The proportion of death in our case is lower than many other studies [17, 20, 28]. There are also other recent researches that have reported a lower AIDS related death rate in Ethiopia [29,30,31,32]. This could be partly attributed to the effects of UTT program implementation in Ethiopia.

Change in treatment regimen, patient condition during admission, program organization, residence and multitude of other factors significantly contribute for the difference in survival rate. With all this benefits early initiation of treatment with UTT program reduced mortality [17, 28]. Generally, in Ethiopia it was noted from WHO reports and previous studies that the success rate was higher in both of HIV treatment programs but more positive outcomes are found on UTT program [1, 2, 28].

In line with finding of this study, many other model based researches have reported that UTT program will reduce mortality [16, 17, 31]. We hazard of death in CD4 based enrolled individuals was 4 times higher than those who enrolled in UTT program. This is in line with other studies [25,26,27, 33]. This could be due to the fact that UTT program clients are enrolled for treatment soon after diagnosis when many of them are at higher CD4 count and better overall health conditions [17, 26]. This could result in low prevalence of co-infection, low probability of drug interaction and side effects and overall better compliance. Owing to the aforementioned positive attributes of UTT program the hazard of mortality has reduced.

Patients living in rural setups were two and half times more likely to die than urban resident patients. This may be due to better drug adherence, accessibility of service, and knowledge difference. Likewise, patients who have developed treatment failure were four times more likely to die than their counter parts. In many researches it was reported that treatment failure is a strong marker of mortality while up on treatment [3, 15, 17]. This may be due to increased viral load and development of secondary infections [22, 33].

Similarly, the risk of death in patients who developed new OIs was 3.66 (95% CI [2.4–5.6], p value < 0.001) times higher than those who did not develop new OIs. Also the increment of base line CD4 count by one unit reduces the probability of death by 0.4%. On the other hand the likely hood of mortality was increased by 5% as age increased by a year.

Strength and limitation of the study

This research evaluated the impact of UTT in clinical setups, which may be the first to do so in the country. Therefore, it may help to know the case in the real scenario. Since the outcome is death; it is easy to establish temporal relationship with predictor variables that are documented at time of admission. On the other hand, incompleteness of information and reliability of the recorded data remains a major concern, since the data is obtained from record review. Also, facility related factors were not assessed in the study.

Conclusion and recommendations

In this study the overall incidence density rate (IDR) of death in the cohort is lower than other studies. Similarly, IDR is lower in clients enrolled by UTT program. The cumulative probability of survival and overall mean survival time is higher in the UTT program and the overall value is comparable with other researches. Treatment outcomes measured in terms of favorable outcome (alive on treatment), death, and default rate were comparable to other reports as well. The main predictors of mortality were age, residence, base line CD4 count, program of enrolment, development of new OIs and treatment failure. Therefore, intervention to further reduce deaths has to focus on facilitating the UTT program to initiate treatment as early as possible and prevention of new OIs and treatment failure is needed. The finding of this research may provide necessary information in areas of improvement; however further research is needed to give policy level recommendations.

Availability of data and materials

Data is available and can be found upon request of the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- ART:

-

Antiretroviral therapy

- AOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratio

- cART:

-

Combined antiretroviral therapy

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- IDR:

-

Incidence density rate

- IRIS:

-

Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome

- OIs:

-

Opportunistic infections

- PLWHA:

-

People living with HIV/AIDS

- UTT:

-

Universal test and treat

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). UNAIDS Data. 2017.

Ethiopian Public Health Institute. HIV related estimates and projections for Ethiopia—2017. Addis Ababa: Ethiopian Public Health Institute; 2017.

World Health Organization. Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection. 2nd edition. Geneva: WHO; 2016. http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/arv/arv2016/en/.

Gardner EM, McLees MP, Steiner JF, Del Rio C, Burman WJ. The spectrum of engagement in HIV care and its relevance to test-and-treat strategies for prevention of HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(6):793–800.

MacCarthy S, Hoffmann M, Ferguson L, Nunn A, Irvin R, Bangsberg D, et al. The HIV care cascade: models, measures and moving forward. J Int AIDS Soc. 2015;18(1):19395.

Okeke NL, Ostermann J, Thielman NM. Enhancing linkage and retention in HIV care: a review of interventions for highly resourced and resource-poor settings. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2014;11(4):376–92.

Garnett G, Baggaley RF. Treating our way out of the HIV pandemic: could we, would we, should we? Lancet. 2008;373:9–11.

World Health Organization (WHO). Guideline on when to start antiretroviral therapy and on pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015.

UNAIDS. Ending AIDS progress towards the 90-90-90 targets. Global AIDS update. Geneva; 2017.

World Health Organization. WHO HIV policy adoption and implementation status in countries fact sheet. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019.

Williams I, Churchill D, Anderson J, Boffito M, Bower M, Cairns G, et al. British HIV association guidelines for the treatment of HIV-1-positive adults with antiretroviral therapy 2012. HIV Med. 2012;13(Suppl 2):1–85.

European AIDS Clinical Society. Guidelines version 7.0. 2013. http://www.eacsociety.org. Accessed 26 Jan 2019.

UNAIDS. UNAIDS 90-90-90 an ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2014.

Montaner JS, Lima VD, Harrigan PR, Lourenço L, Yip B, Nosyk B, et al. Expansion of HAART coverage is associated with sustained decreases in HIV/AIDS morbidity, mortality and HIV transmission: the “HIV treatment as prevention” experience in a Canadian setting. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e87872.

Baeten JM. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):399–410.

Brown T, Bao L, Raftery AE, Salomon JA, Baggaley RF, Stover J, et al. Modelling HIV epidemics in the antiretroviralera: the UNAIDS estimation and projection package 2009. Sex Transm Infect. 2010;86:ii3–10.

Granich M. Universal voluntary HIV testing with immediate antiretroviral therapy as a strategy for elimination of HIV transmission: a mathematical model. Lancet. 2009;373(9657):48–57.

Bendavid E, Margaret L, Wood R, Douglas K. Comparative effectiveness of HIV testing and treatment in highly endemic regions. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(15):1347–54.

Danel C, Moh R, Gabillard D, Badje A, Le Carrou J, Ouassa T, et al. A trial of early antiretrovirals and isoniazid preventive therapy in Africa. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(9):808–22.

Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(6):493–505.

Hogan CM, Degruttola V, Sun X, Fiscus SA, Del Rio C, Hare CB, et al. The setpoint study (ACTGA5217): effect of immediate versus deferred antiretroviral therapy on virologic set point in recently HIV1-infected individuals. J Infect Dis. 2012;205(1):87–96.

Pilcher CD, Ospina-Norvell C, Dasgupta A, Jones D, Hartogensis W, Torres S, et al. The effect of same-day observed initiation of antiretroviral therapy on HIV viral load and treatment outcomes in a US public health setting. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;74(1):44–51.

Rosen S, Maskew M, Fox MP, Nyoni C, Mongwenyana C, Malete G, et al. Initiating antiretroviral therapy for HIV at a patient’s first clinic visit: the RapIT randomized controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2016;13(5):e1002015.

Mbonye M, Seeley J, Nalugya R, Kiwanuka T, Bagiire D, Mugyenyi M, et al. Test and treat: the early experiences in a clinic serving women at high risk of HIV infection in Kampala. AIDS Care Psychol Socio-Med Asp AIDS/HIV. 2016;28:33–8.

Uthman OA, Okwundu C, Gbenga K, Volmink J, Dowdy D, Zumla A, et al. Optimal timing of antiretroviral therapy initiation for HIV-infected adults with newly diagnosed pulmonary tuberculosis: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(1):32–9.

Abay SM, Deribe K, Reda AA, Biadgilign S, Datiko D, Assefa T, et al. The effect of early initiation of antiretroviral therapy in TB/HIV-coinfected patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2015;14(6):560–70.

Adakun SA, Siedner MJ, Muzoora C, Haberer JE, Tsai AC, Hunt PW. Higher baseline CD4 cell count predicts treatment interruptions and persistent viremia in patients initiating ARVs in rural Uganda. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;62(3):317–21.

Das M. Decreases in community viral load are accompanied by reductions in new HIV infections in San Francisco. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(6):e11068.

Opravil M, Ledergerber B, Furrer H, Hirshel B, Imhof A, Gallant S, et al. Clinical efficacy of early initiation of HAART in patients with asymptomatic HIV infection and CD4 cell count > 350. AIDS. 2002;16:1371–81.

Phillips A, Staszewski S, Weber R, Kirk O, Francioli P, Miller V, et al. HIV viral load response to antiretroviral therapy according to the baseline CD4 cell count and viral load. J Am Med Assoc. 2001;286:2560–7.

Grant P, Tierney C, Katzenstein D. Association of baseline viral load, CD4 count, and Week 4 virologic response (VR) with virologic failure (VF) in ACTG study A5202 [Abstract 535]. In: 18th conference on retroviruses and opportunistic infections, Boston, Massachusetts, 27 February–2 March 2011.

Gras L, Kesselring A, Griffin J, van Sighem AI, Fraser C, Ghani AC, et al. CD4 cell counts of 800 cells/mm3 or greater after 7 years of highly active antiretroviral therapy are feasible in most patients starting with 350 cells/mm3 or greater. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;45:183–92.

Lundgren JD, Babiker AG, Gordin F, Emery S, Grund B, Sharma S, et al. Initiation of antiretroviral therapy in early asymptomatic HIV infection. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(9):795–807.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to sincerely thank Head of the health department, data collectors, and others who ever contributed for this work. We would also like to acknowledge Wolkite University for facilitating the study.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have made substantial intellectual contributions to conception, design, and acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data to this study. They also have been involved in drafting the manuscript, approved the final manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical clearance was obtained from institutional review board of Wolkite University. Permission to conduct the study was obtained from Gurage zone and district health departments. Permission was obtained from each clinic officials. All data obtained from records were kept confidential by using codes instead of any personal identifiers. The finding of the study is believed to benefit the clients indirectly through improvement of health care system; which will maximize the benefit and minimize the harm.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The author declare no conflict of interest with anybody.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Girum, T., Yasin, F., Wasie, A. et al. The effect of “universal test and treat” program on HIV treatment outcomes and patient survival among a cohort of adults taking antiretroviral treatment (ART) in low income settings of Gurage zone, South Ethiopia. AIDS Res Ther 17, 19 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12981-020-00274-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12981-020-00274-3