Abstract

Background

Caesarean sections (CS) are increasing worldwide. Financial incentives and related regulatory and legislative factors are important determinants of CS rates. This scoping review examines the evidence base of financial, regulatory and legislative interventions intended to reduce CS rates.

Methods

We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL and two trials registers in June 2019. Both experimental and observational intervention studies were eligible for inclusion. Primary outcome measures were: CS, spontaneous vaginal and instrumental birth rates. We assessed quality of evidence using Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) method.

Results

We identified 9057 articles and assessed 65 full-texts. We included 16 observational studies. Most of the studies were conducted in high-income countries.

Three studies assessed payment methods for health workers: equalising physician fees for vaginal and caesarean delivery reduced CS rates in one study; however, little or no difference in CS rates was found in the remaining two studies.

Nine studies assessed payment methods for health organisations:

There was no difference in CS rates between diagnosis-related group (DRG) payment system compared to fee-for-service system in one study. However, DRG system was associated with lower odds for CS in another study.

There was little or no difference in CS rates following implementation of global budget payment (GBP) system in two studies.

Vaginal birth after caesarean section (VBAC) increased after implementation of a case-based payment system in one study. Caesarean section increased while VBAC rates decreased following implementation of a cap-based payment system in another study.

Financial incentive for providers to promote vaginal delivery combined with free vaginal delivery policy was found to reduce CS rates in one study.

Studied regulatory and legislative interventions (comprising legislatively imposed practice guidelines for physicians in one study and multi-faceted strategy which included policies to control CS on maternal request in another study) were found to reduce CS rates.

The GRADE quality of evidence varied from very low to low.

Conclusions

Available evidence on the effects of financial and regulatory strategies intended to reduce unnecessary CS is inconclusive given inconsistency in effects and low quality of the available evidence. More rigorous studies are needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Plain English summary

Caesarean sections are increasing worldwide. Financial incentives and related regulatory and legislative factors are important determinants of caesarean section rates. Financial interventions may influence caesarean section rates in various ways: for example, equalizing the payment between caesarean and vaginal delivery may reduce health provider incentive to perform unnecessary caesarean section; increasing the cost of caesarean section to patients may disincentivize women from choosing medically unnecessary caesarean section.

However, in previous systematic reviews of non-clinical interventions intended to reduce unnecessary caesarean section, several financial, regulatory and legislative interventions were excluded due to weaknesses in study designs. The real-world effect of these interventions therefore remain unclear. This scoping review addresses this gap in the literature.

We searched multiple databases for published, unpublished and ongoing studies in June 2019. Sixteen studies met our predetermined inclusion criteria and were included in the review.

Most of the studies assessed financial interventions comprising: different payment methods for health workers (such as equalizing physician fees for vaginal and caesarean deliveries); different payment methods for health organisations (such as budget systems where the hospital is given a fixed amount of money in advance to cover expenses for a fixed period). The quality of evidence varied from very low to low. Overall, studied interventions resulted in mixed-effects on caesarean section rates.

In summary, the available evidence on the effects of financial and regulatory strategies intended to reduce unnecessary caesarean section rates is inconclusive given inconsistency in effects and low quality of the available evidence. More rigorous studies are needed.

Background

Caesarean section (CS) is a surgical procedure that saves lives when used for medically indicated reasons (e.g. abnormal presentation or fetal distress). Caesarean sections are increasing worldwide with wide differences in use within and between countries [1,2,3]. Latest trends analysis shows that between 2000 and 2015, the global average CS rate increased by 9.0% (from 12.1 to 21.1%) [4]. Latin America and the Caribbean had the highest CS rates (44.3%), followed by North America (32.0%), Middle East and North Africa (29.6%), East Asia and Pacific (28.8%), Eastern Europe and Central Asia (27.3%), Western Europe (26.9%), South Asia (18.1%), Eastern and Southern Africa (6.2%) and West and Central Africa (4.1%) [4]. The steady increase in CS has, however, not been accompanied by clear health or other benefits for women and their babies [5]. This evidence suggests that the majority of CS are medically unnecessary and that many women and their babies are without the benefits of vaginal birth [6, 7]. These advantages compared to CS include: women’s shorter physical and psychological recovery period after birth, increased likelihood of successful breastfeeding, natural physiological adaptation to the external environment and improved immunity of the baby, and support for the baby’s longer-term growth, health and development [8, 9].

Underuse and lack of access to CS, particularly among rural and disadvantaged communities in low resource settings, can result in unnecessary birth complications and deaths of women and their babies [10]. Conversely, overuse (use of CS without medically indicated reasons) is associated with increased risk of harm for women and their babies (e.g. infections, bleeding, complications related to use of anaesthesia, infant respiratory problems such as asthma, obesity in children and added complications for the women in subsequent pregnancies such as uterine rupture, abnormal placenta, miscarriage, stillbirth, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), among others) [11,12,13]. Caesarean sections are expensive, and their overuse has resource implications particularly for countries where essential interventions remain unavailable, or where inequalities in access to these services remain. The steady increase in CS in the last decades coupled with the limited success of tested interventions to stop and reverse this trend have raised concerns among governments and health care professionals [6, 7].

A range of clinical and non-clinical interventions intended to reduce CS have been assessed in previous systematic reviews [14,15,16]. Financial factors and related regulatory and legislative factors are important determinants of CS practices [17, 18]. There are various pathways through which targeted financial interventions may reduce unnecessary CS and ultimately improve maternal and neonatal health outcomes: (1) reducing health provider incentives to perform unnecessary CS, by equalizing the payment between CS and vaginal delivery or increasing vaginal delivery fee higher than CS fee; (2) disincentivizing women from choosing medically unnecessary CS, by increasing the cost of CS to patients, or reducing the costs of vaginal deliveries (e.g. free vaginal delivery policies); (3) pay-for-performance, that involves rewarding hospitals for performance in reducing CS or increasing vaginal deliveries; (iv) global or standardised budget caps (including capitation budget) for all patients and all services, by reducing costs for entire patient populations, rather than for individual cases, including switching from CS to vaginal delivery to save on costs and ensure a higher overall surplus. Similarly, regulatory and legislative interventions may reduce unnecessary CS by reducing the discretion of individual clinicians to perform CS that are convenient for them, or that involve requests from patients in the absence of any maternal or fetal indications.

However, in previous systematic reviews of non-clinical interventions, several financial, regulatory and legislative interventions were excluded [15] due to weaknesses in study designs (e.g. cross-sectional, case study designs). The real-world impact of these interventions, often studied in ways not amenable to systematic reviews of interventions (e.g. case studies) therefore remain uncertain. Furthermore, factors that may influence the implementation of the interventions, including challenges and opportunities, remain understudied.

This scoping review examines the evidence base of financial, regulatory and legislative interventions intended to reduce unnecessary CS. The specific objectives are to:

-

Describe the characteristics of identified financial, regulatory and legislative interventions intended to reduce unnecessary CS

-

Assess the safety and effectiveness of these financial, regulatory and legislative interventions

-

Summarise evidence on the lessons learnt on the design and implementation of identified financial, regulatory and legislative interventions to inform policy, implementation and future research.

Methods

Study selection criteria

Types of studies

Studies that assessed the effect of financial, regulatory and legislative interventions for reducing CS using the following designs were eligible for inclusion: randomised trials, non-randomised trial, controlled before-after (CBA) studies, interrupted time-series (ITS) studies, cohort studies, large scale intervention case studies, pre-post studies intervention studies, cross-sectional studies (with appropriate analysis to control for confounding), and mixed-methods (quantitative and qualitative) studies.

Types of participants

Studies involving the following groups were eligible for inclusion: (1) low-risk pregnant women seeking antenatal, labour and delivery care in health care facilities (term, singleton, cephalic pregnancies with or without a previous caesarean; women in Robson classification groups 1 through 5 [19]); (2) healthcare providers who work with pregnant women (nurses, midwives, physicians) during antenatal care, labour or delivery; (3) healthcare facilities, hospitals or health systems that provide delivery care to pregnant women.

Types of interventions

Financial, regulatory and legislative interventions eligible for inclusion are summarised in Table 1. Studies of interventions aimed at increasing CS use were excluded.

Types of outcome measures

Main outcomes

Rate of CS and rate of all other modes of delivery (spontaneous vaginal birth, elective CS, emergency CS, instrumental vaginal birth).

Secondary outcomes

Perineal/vaginal trauma, birth trauma, perinatal asphyxia, serious maternal morbidity, minor maternal morbidity, long-term maternal outcomes, long-term infant outcomes, maternal birth experience, health care resource utilization (Table 2).

Studies that only reported secondary outcomes were not included.

Settings

All settings (Low, Middle, High-income countries).

Search methods for identification of studies

The following sources were searched in June 2019 for eligible published, unpublished and ongoing studies (Additional file 1): MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, GIM (Global Index Medicus; http://www.globalhealthlibrary.net), Ebsco MultiDisciplinary Databases (http://www.ebsco.com), WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (http://www.who.int/ictrp/en/), ClinicalTrials.gov (https://www.clinicaltrials.gov), and reference lists of identified trials and reviews. The searches were done without any language, date or publication status restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies and data extraction

The identified articles were entered in Covidence (https://www.covidence.org/). Three reviewers (NO, CY, APB) independently screened titles, abstracts and full texts of identified articles and applied the pre-specified study eligibility criteria to select studies. Two reviewers (NO, CY) extracted and entered data (e.g. on study settings, participants, interventions, outcome measures) independently and in duplicate into pilot-tested data extraction forms. Disagreements were resolved by discussion.

Assessment of quality of included studies

Risk of bias in each study was assessed independently and in duplicate by two reviewers (NO, CY) and reported as one element of Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) [20]. Risk of bias domains assessed included the likelihood of bias attributable to confounding, selection of participants in the study, classification of interventions, deviations from intended interventions, missing data, measurement of outcomes, and selection of reported results.

The certainty of the body of evidence for each outcome (sometimes referred to as “quality of evidence” or “confidence in the estimate”) was assessed using the GRADE approach [20]. Based on this approach, the certainty of evidence for each outcome is rated as “High”, “Moderate”, “Low” or “Very low” based on a set of criteria. The certainty of evidence from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) begin at “High” and can be downgraded in consideration of five factors: risk of bias or limitations in the design and conduct of study, directness of evidence, consistency of results, precision of effect estimates and publication bias. Certainty of evidence from observational studies begin at “Low” and can be upgraded in consideration of three factors: magnitude of effect estimate, dose-response gradient, and influence of residual plausible confounding.

Data synthesis

We did not combine results using statistical methods (meta-analysis) as the included studies utilised varied designs (RCTs, controlled before-after, interrupted time series, pre-post intervention studies) and examined diverse interventions (financial, regulatory, legislative strategies). Individual study results are described in the Results section.

For interrupted time series studies, we reported two effect sizes used to measure the intervention effect: change in level (also called “step change”) and change in trend (also called “change in slope”) before and after the intervention [21]. Change in level is the difference between the observed level at the first intervention time point and that predicted by the pre-intervention time trend; change in trend is the difference between post- and pre-intervention slopes. A negative change in level and slope indicates a reduction in the event. Where these effect measures were not estimable (e.g. owing to insufficient data), we reported results as reported in the individual studies.

Data on lessons learnt (relating to features, challenges, and opportunities in the design and implementation of studied interventions) were collated based on reports from the included studies.

Results

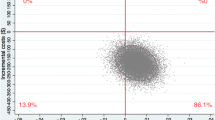

Results of the search

We identified 9057 records from electronic databases, clinical trials registries and other resources. We excluded 8992 records following a review of titles and abstracts. We retrieved the full texts of the remaining 65 records for detailed eligibility assessment. We excluded 49 records due to ineligible interventions (e.g. user fee exemptions designed to increase CS), non-intervention studies and inappropriate outcomes. Overall, 16 studies fulfilled the review inclusion criteria (Fig. 1).

Included studies

The sixteen included studies form the basis of the findings summarised in this review (Table 3). These studies were conducted in six different countries: North America (5 studies in USA); Latin America (1 study in Brazil); Western Asia (1 study in Iran); East Asia (2 studies in China; 5 studies in Taiwan; 2 studies in South Korea).

Interventions

Details of the interventions are summarised in Table 4.

Financial interventions

Twelve studies published between 1996 and 2019 assessed financial interventions [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33].

Study designs were varied: controlled before-after study [25], interrupted time series studies [22,23,24, 28, 29, 33]; uncontrolled before-after study [30]; pre-post comparative studies [27, 31, 32]; and retrospective cohort studies [26].

Ten studies were done in high-income countries: USA [23, 28, 31], Taiwan [22, 24, 27, 29, 30], South Korea [25, 26]. Two studies were done in middle-income countries: China [32] and Iran [33]. There were no studies from low-income countries.

The specific financial interventions were:

-

Health worker payment methods: Equalising physician reimbursement fees for vaginal and caesarean delivery [22,23,24].

-

Health organization payment methods: diagnosis-related group (DRG) payment system [25, 26]; global budget payment (GBP) system [27,28,29]; case-based payment system [30]; and cap-based payment system [31, 32].

-

Other financial interventions: Financial incentive and free vaginal delivery policy [33].

Regulatory and legislative interventions

Two studies assessed regulatory and legislative interventions: interrupted time series study (USA) [34] and pre-post intervention study (China) [35].

The specific regulatory and legislative interventions were: legislatively imposed practice guidelines [34]; and multifaceted institutional and policy interventions [35].

Other interventions

Two studies, retrospective cohort study (USA) [36] and interrupted time series study (Brazil) [37], assessed the following interventions: “hard stop” policy limiting elective inductions and caesarean births [36]; and multifaceted quality improvement initiative (“Appropriate Birth”) [37].

Effects of interventions

Details of the effects of the interventions and certainty of evidence ratings are summarised in Table 5.

Financial interventions

Equalising physician reimbursement fees for vaginal and caesarean delivery

The three studies that examined programs involving equalising physician fees for vaginal and caesarean deliveries reported mixed-effects on CS rates [22,23,24]. Two studies found little or no difference in CS rates following equalising fees by National Health Insurance (NHI) in Taiwan [22, 24]. One of the studies [24] reported a non-significant change in CS from 24.2 to 30.5%. In the other study [22], the change in the level of total CS rate was − 1.68 (95% CI − 2.3 to − 1.07) while the change in trend was − 0.004 (95% CI − 0.05 to 0.04). Effects of equalising physician fees was unclear in the third study conducted in USA [23]). In this study CS rates decreased by 1.2% but absolute numbers for the change were not reported (re-analysis to determine statistical significance was therefore not possible). The certainty of evidence varied from very low [22, 23] to low [24].

Diagnosis-related group payment system

The two studies from South Korea that assessed diagnosis-related group (DRG) payment systems found mixed-effects on CS rates [25, 26]. The first study [25] explored the impact of a DRG payment system with fixed reimbursement for physicians regardless of the cost of the caesarean procedure. The findings showed that, in hospitals that voluntarily adopted this practice, longer periods of DRG adoption were associated with lower odds for CS (OR 0.997, 95% CI 0.996 to 0.998). However, hospitals that underwent mandatory DRG adoption had higher CS rates (37.3% vs. 36.8%). The second study [23, 26] found no differences in CS rates between DRG payment systems operated by voluntarily participating hospitals compared to fee-for-service systems. The certainty of evidence was low in both studies.

Global budget payment system

Mixed-effects were observed across groups of women of different ages following implementation of a global fee policy for caesarean and vaginal deliveries and co-payment from patients for non-medically indicated caesareans in Taiwan (effect estimates presented in Table 5) [27]. In USA [28], a global payment policy (i.e. a single facility or professional services payment regardless of delivery mode) resulted in a decrease in overall CS by 3.2 percentage points. An additional study from Taiwan [29] found no significant effect on CS following implementation of a GBS and Hospital-Based Self-Management (HBSM) policy which involved post-operative peer reviews and audits of CS (effect estimates presented in Table 5). The certainty of evidence in each of the studies was low.

Case-based payment system

Vaginal birth after caesarean section (VBAC) increased by 6.1% (p < 0.001) after implementation of a case-based payment system in one study conducted in Taiwan [30]. The certainty of evidence was very low.

Cap-based payment system

Implementation of a cap-based payment system (i.e. HealthChoice managed care program) resulted in an increase in CS (from 21.1 to 24.0%) and a decrease in VBAC (from 4.7 to 3.6%) in one study from USA [31]. An additional study (China) [32] assessed the effect of a cap-based Maternity Insurance Scheme (MIS) designed to limit unnecessary procedures by refusing to reimburse hospitals above the price of a cap. While all medical expenditures increased over time, the rate of expenditure on CS decreased as compared to other patient services in the hospital. Changes in CS rates were not reported. The certainty of evidence was low in both studies.

Financial incentive and free vaginal delivery policy

One study conducted in Iran [33] reported an increase in CS following implementation of a financial incentive for providers to promote vaginal delivery combined with free vaginal delivery policy (rate of CS increased by 0.0017% per month in the post-intervention period). The certainty of evidence was low.

Regulatory and legislative interventions

Studied regulatory and legislative interventions (comprising legislatively imposed practice guidelines for physicians [34] and multi-faceted strategy which included policies to control caesarean delivery on maternal request (CDMR) [35]) were found to reduce CS rates. In one of the studies (USA) [34], repeat CS decreased by a greater magnitude (5.7%) following implementation of legislatively imposed practice guidelines on CS for obstetricians (which included the establishment of peer review boards at hospitals for quality control). In the other study (China) [35] the overall CDMR rate decreased from 54.4 to 46.2% (p < 0.001) following implementation of the policy interventions. The certainty of evidence was low in both studies.

Other interventions

One study (USA) examined the effect of a “Hard stop” policy limiting elective inductions and caesarean births before 39 weeks of gestation [36]. In order to limit early-term deliveries, the policy required a review and approval for any delivery without documented indication prior to 39 weeks of gestation. The study found no effect on elective CS (OR 1.00, 95% CI 0.97 to 1.03). An additional study (Brazil) [37] assessed the effect of a multifaceted quality improvement initiative (“Appropriate Birth”), that among other change packages, included new contracts between payers and providers and between health plan and hospital creating incentives for quality and safety. Vaginal births increased following implementation of the quality improvement initiative (relative increase of 1.62, 95% CI 1.27 to 2.07). The GRADE certainty of evidence was low in both studies.

Discussion

Summary of main results

This scoping review identified diverse financial and legislative strategies intended to reduce CS rates, mostly from high income countries. Most of the studies assessed reimbursement strategies for health providers and organisations. Only two studies assessed regulatory and legislative strategies. Effects of the interventions were inconsistent across settings (for example, a global payment policy comprising a single facility or professional services payment regardless of delivery mode resulted in a decrease in CS in USA [28], but no effect was found in Taiwan [29]). For some interventions, effects were contradictory given hypothesised mechanisms of action (e.g. increased CS rates following cap-based payment system in USA [31]). Overall, our confidence in these findings is low given limitations in the available evidence. It is plausible that confounding due to observational designs impacted on the observed effects (for example, it was unclear in most of the studies whether the intervention occurred independent of other changes over time).

Limitations of the evidence

None of the studies was done in a low-income country. Limited data was available on maternal and neonatal outcomes and health care resource utilisation, including impact on medical costs. This represents a significant gap in knowledge about the studied interventions.

The summarised evidence is mostly drawn from single studies assessing distinct interventions with diverse study designs. We were therefore unable to pool outcome data in order to increase sample size. Also, most of the evaluations were conducted a few years after the introduction of the interventions or policy reforms. Longer-term evaluations would be beneficial to reliably determine the impact and sustainability of the interventions.

Most of the studies do not provide sufficient details about the different components of the interventions to make it possible to determine their mechanisms of action, and to facilitate replication in other contexts. Evaluating and reporting effects of different intervention components can inform the extent to which various components influence CS rates and, therefore, inform optimal design of financial and legislative interventions.

The reliability of the effects of the interventions on CS rates depend on the quality of data available in the study sites. Coding errors limit reliability and validity of measurements [31]. In addition, coding practices in diagnosis-related payment systems may vary limiting comparisons across hospitals and sites. Thus, robust, standardized health information system for routine data collection are needed to support reliable monitoring of the impact of studied financial and regulatory interventions.

It was not possible to determine the appropriateness or indications of the reported CS, as none of the studies reported clinical data on the CS performed. It is therefore unclear whether the reported changes in CS rates were all in those considered unnecessary. Given these limitations, the review findings should be interpreted cautiously. Lastly, although our searches were relatively comprehensive, it is possible that we did not identify some relevant studies, particularly as no grey literature sources were searched.

Implications for future research

The findings of this review have important implications for future research. First, the impact of different financial, regulatory and legislative strategies should be explored using larger sample sizes, for example, by analyses of pooled health facility survey or Multiple Indicator Cluster (MICS) data from different countries. Second, there were inconsistencies in the way that studies measured and reported CS, making it difficult to compare findings of the studies. More systematic and consistent reporting of CS would be useful to aid synthesis and interpretation of findings across studies and countries. For this, WHO proposes Robson classification system as a global standard [38]. Third, for financial reforms that involve a higher reimbursement fee for vaginal compared to caesarean deliveries, a monitoring system for vaginal deliveries is needed, given possible unintended consequences of inappropriate vaginal deliveries among high risk groups for CS. There is a continual need for replication of studies in different countries and populations with different health needs, particularly as most of the interventions were evaluated in single studies with weak study designs.

None of the 16 included studies utilised a randomised design. This suggests that there might be challenges to using randomised study designs for evaluating financial, legislative and regulatory interventions (e.g. randomisation of policy reforms may not be feasible in practice). Changes in payment systems or legislative policies are often implemented suddenly or nationwide, which prevents the use of randomised studies. In addition, identification of comparable control groups remains a challenge given inherent differences in contexts such as health systems, policy environments and population groups. Given these methodological challenges, balancing pragmatism and research rigour is encouraged in evaluating the effects of financial, regulatory and legislative interventions [39]. Similarly, new methods for assessing the quality of evidence optimised for studied and related policy interventions should be developed (existing systems such as GRADE may not be reliable given the highlighted methodological challenges in the conduct of primary studies). Well conducted controlled before and after designs and interrupted time series, with appropriate analysis to control for contextual factors and possible confounders, appear feasible alternatives to randomised designs.

Key lessons learned

A number of lessons relevant for the design and implementation of financial and legislative interventions emerged from the included studies. Several factors may have influenced the reported effects of the interventions: for example, it is possible that the 21% shift in payments in fee equalisation insurance reform in USA [23] may not have been enough to change physician behaviour to reduce CS. Given this, it is important that appropriate reimbursement is provided to healthcare providers to reduce economic incentives on decisions regarding the delivery method. If providers are reimbursed according to their performance, clinical condition would be considered to be more important when deciding on the mode of delivery, and this could play a role in decreasing the high rate of CS [25]. Also, mere dissemination of guidelines by a state agency did not achieve the magnitude and specificity desired without an explicit implementation program, in the legislatively imposed practice guidelines in USA [34]. Thus, dissemination of guidelines should be accompanied by systematic and detailed evidence-based implementation plan to improve effectiveness. These findings emphasize the need for multifaceted interventions targeting all key stakeholders to address caesarean over-use.

Conclusions

The available evidence on the effects of financial and regulatory strategies intended to reduce unnecessary CS is inconclusive given inconsistency in effects and low quality of the available evidence. More rigorous studies and new ways of assessing the impact of financial and legislative interventions intended to reduce unnecessary CS are needed.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its additional files.

Abbreviations

- GBP:

-

Global budget payment

- CBA:

-

Controlled before-after study

- CDMR:

-

Caesarean delivery on maternal request

- CINAHL:

-

Cumulative index to nursing and allied health

- CS:

-

Caesarean section

- DRG:

-

Diagnosis-related group

- GBP:

-

Global budget payment

- GIM :

-

Global Index Medicus

- GRADE:

-

Grading of recommendations, assessment, development and evaluation

- HBSM:

-

Hospital-based self-management

- ITS:

-

Interrupted time series study

- LILACS:

-

Latin America and the Caribbean Literature on Health Sciences

- MICS:

-

Multiple indicator cluster

- MIS:

-

Maternity insurance scheme

- NHI:

-

National Health Insurance

- PTSD:

-

Post-traumatic stress disorder

- RCT:

-

Randomised controlled trial

- VBAC:

-

Vaginal birth after caesarean section

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Betrán AP, Merialdi M, Lauer JA, Bing-shun W, Thomas J, et al. Rates of caesarean section: analysis of global, regional and national estimates. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2007;21(2):98–113.

Betrán AP, Ye J, Moller A-B, Zhang J, Gülmezoglu AM, Torloni MR. The increasing trend in caesarean section rates: global, regional and national estimates: 1990–2014. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0148343.

Boatin AA, Schlotheuber A, Betran AP, Moller AB, Barros AJD, Boerma T, et al. Within country inequalities in caesarean section rates: observational study of 72 low- and middle-income countries. BMJ. 2018;360:k55.

Boerma T, Ronsmans C, Melesse DY, Barros AJD, Barros FC, Juan L, Ann-Beth Moller AB, et al. Global epidemiology of use of and disparities in caesarean sections. Lancet. 2018;392:1341–8.

Lumbiganon P, Laopaiboon M, Gülmezoglu AM, Souza JP, Taneepanichskul S, Ruyan P, et al. Method of delivery and pregnancy outcomes in Asia: the WHO global survey on maternal and perinatal health 2007-08. Lancet. 2010;375(9713):490–9.

WHO statement on caesarean section rates. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015. Available from: https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/maternal_perinatal_health/cs-statement/en/. Accessed 11 Aug 2020.

Betran AP, Ye J, Torloni MR, Zhang JJ, Gulmezoglu AM. WHO working group on caesarean section: WHO statement on caesarean section rates. BJOG. 2016;123(5):667–70.

Buhimschi CS, Buhimschi IA. Advantages of vaginal delivery. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2006;49(1):167–83.

Dahlen HG, Kennedy HP, Anderson CM, Bell AF, Clark A, Foureur M, et al. The EPIIC hypothesis: intrapartum effects on the neonatal epigenome and consequent health outcomes. Med Hypotheses. 2013;80(5):656–62.

Sobhy S, Arroyo-Manzano D, Murugesu N, Karthikeyan G, Kumar V, Kaur I, et al. Maternal and perinatal mortality and complications associated with caesarean section in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2019;393(10184):1973–82.

Keag OE, Norman JE, Stock SJ. Long-term risks and benefits associated with cesarean delivery for mother, baby, and subsequent pregnancies: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2018;15:e1002494.

Sandall J, Tribe RM, Avery L, Mola G, Visser GH, Homer CS, et al. Short-term and long-term effects of caesarean section on the health of women and children. Lancet. 2018;392(10155):1349–57.

Souza JP, Gülmezoglu A, Lumbiganon P, Laopaiboon M, Carroli G, Fawole B, et al. Caesarean section without medical indications is associated with an increased risk of adverse short-term maternal outcomes: the 2004-2008 WHO global survey on maternal and perinatal health. BMC Med. 2010;8(71).

Catling-Paull C, Johnston R, Ryan C, Foureur MJ, Homer CS. Clinical interventions that increase the uptake and success of vaginal birth after caesarean section: a systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2011;67(8):1646–61.

Chen I, Opiyo N, Tavender E, Mortazhejri S, Rader T, Petkovic J, et al. Non-clinical interventions for reducing unnecessary caesarean section. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;9:CD005528.

Hartmann KE, Andrews JC, Jerome RN, Lewis RM, Likis FE, McKoy JN, et al. Strategies to reduce cesarean birth in low-risk women. Comparative effectiveness review no. 80. AHRQ publication no. 12(13)-EHC128-EF. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2012.

Comfort AB, Peterson LA, Hatt LE. Effect of health insurance on the use and provision of maternal health services and maternal and neonatal health outcomes: a systematic review. J Health Popul Nutr. 2013;4(Suppl 2):81–105.

Stafford RS. Alternative strategies for controlling rising cesarean section rates. JAMA. 1990;263(5):683–7.

Robson MS. Classification of caesarean sections. Fetal Matern Med Rev. 2001;12:23–39.

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Vist GE, Falck-Ytter Y, Schünemann HJ, et al. Rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations: what is “quality of evidence” and why is it important to clinicians? BMJ. 2008;336(7651):995–8.

Bernal JL, Cummins S, Gasparrini A. Interrupted time series regression for the evaluation of public health interventions: a tutorial. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(1):348–55.

Lo JC. Financial incentives do not always work – an example of cesarean sections in Taiwan. Health Policy. 2008;88(1):121–9.

Keeler EB, Fok T. Equalizing physician fees had little effect on cesarean rates. Med Care Res Rev. 1996;53(4):465–71.

Liu T, Chen C, Tsai Y, Lin H. Taiwan's high rate of cesarean births: impacts of national health insurance and fetal gender preference. Birth. 2007;34(2):115–22.

Kim SJ, Han KT, Park EC, Park HK. Impact of a diagnosis-related group payment system on cesarean section in Korea. Health policy. 2016;120(6):596–603.

Lee K, Sangil L. Effects of the DRG-based prospective payment system operated by the voluntarily participating providers on the cesarean section rates in Korea. Health Policy. 2007;81(2–3):300–8.

Chen CS, Liu TC, Chen B, Lin CL. The failure of financial incentive? The seemingly inexorable rise of cesarean section. Soc Sci Med. 2014;101:47–51.

Kozhimannil KB, Graves AJ, Ecklund AM, Shah N, Aggarwal R, Snowden JM. Cesarean delivery rates and costs of childbirth in a state Medicaidprogram after implementation of a blended payment policy. Med Care. 2018;56(8):658–64.

Liu CM, Lin YJ, Su YY, Chang SD, Cheng PJ. Impact of health policy based on the self-management program on cesarean section rate at a tertiary hospital in Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc. 2013;112(2):93–8.

Tsai YH, Huang KC, Soong YK. Impact of case payment on physicians practicing vaginal birth after cesarean section. Taiwan J Public Health. 2006;25(4):283–92.

Misra A. Impact of the HealthChoice program on cesarean section and vaginal birth after C-section deliveries: a retrospective analysis. Matern Child Health J. 2008;12(2):266–74.

Chen C, Cheng Z, Jiang P, Sun M, Zhang Q, Lv J. Effect of the new maternity insurance scheme on medical expenditures for caesarean delivery in Wuxi, China: a retrospective pre/post-reform case study. Front Med. 2016;10(4):473–80.

Karami MB, Mohammad H, Farid N, Homaie RE, Bakhtiar P, Satar R. The impact of health sector evolution plan on hospitalization and cesarean section rates in Iran: an interrupted time series analysis. Int J Qual Health Care. 2018;30(1):75–9.

Studnicki J, Remmel R, Campbell R, Werner DC. The impact of legislatively imposed practice guidelines on cesarean section rates: the Florida experience. American journal of medical quality: the official journal of the American College of Medical. Quality. 1997;12(1):62–8.

Yu Y, Zhang X, Sun C, Zhou H, Zhang Q, Chen C. Reducing the rate of cesarean delivery on maternal request through institutional and policy interventions in Wenzhou, China. PloS one. 2017;12(11):e0186304.

Snowden JM, Muoto I, Darney BG, Quigley B, Tomlinson MW, Neilson D, et al. Oregon's hard-stop policy limiting elective early-term deliveries: association with obstetric procedure use and health outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(6):1389–96.

Borem P, de Cássia SR, Torres J, Delgado P, Petenate AJ, Peres D, et al. A quality improvement initiative to increase the frequency of vaginal delivery in Brazilian hospitals. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135(2):415–25.

Classification R. Implementation manual. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. Available at: https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/maternal_perinatal_health/robson-classification/en/. Accessed 30 Dec 2019.

Portela MC, Pronovost PJ, Woodcock T, Carter P, Dixon-Woods M. How to study improvement interventions: a brief overview of possible study types. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;5:325–36.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Tomas Allen for assistance with the literature searches.

Funding

Not applicable (No funding was received).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NO and APB designed the review methodology. NO, CY and APB reviewed all titles, abstracts, full text articles and selected studies for inclusion. NO, CY and APB extracted data, assessed study quality and analysed data. NO prepared the first draft of the review. All authors participated in the interpretation of results, writing of the manuscript and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.

Search strategy.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Opiyo, N., Young, C., Requejo, J.H. et al. Reducing unnecessary caesarean sections: scoping review of financial and regulatory interventions. Reprod Health 17, 133 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-020-00983-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-020-00983-y