Abstract

Background

Maternal satisfaction towards childbirth service is related to the quality of care. Promotion of patient satisfaction is essential for preventing patient anxiety, promoting treatment adherence, preventing disease, and health promotion. This study was aimed at assessing the satisfaction and associated factors among mothers who visit public health facilities in Adama town for childbirth service.

Methods

An institution based cross-sectional study design was conducted at public health facilities in Adama town from June 01 to June 30, 2018. Four hundred seventy-seven mothers were selected using a systematic random sampling method. Bivariate and multivariate logistic regressions were conducted to identify predictors of maternal satisfaction towards childbirth service by considering p-value less than 0.05.

Results

The study revealed that 357 (74.8%) were satisfied with the services. Factors which showed a significant association with satisfaction were 25–34 age group (AOR; 2.026, 95%CI:1.056,3.887), no formal education (AOR;2.810, 95%CI;1.085,7.278), planned childbirth (AOR; 1.823,95%CI;1.024,3.246), wait time of less than 1 h (AOR;11.620,95%CI;3.619,37.309) and wait time of one to 2 h (AOR;19.620, 95%CI;2.349,68.500).

Conclusion

Three-quarters of the mothers were satisfied with childbirth services. Age, educational status, reason for visit and wait time were found to have a significant association with maternal satisfaction of childbirth services.

Similar content being viewed by others

Plain English summary

Ensuring maternal satisfaction of childbirth services is essential for preventing anxiety, promoting treatment adherence, preventing disease and health promotion. In order to improve future use of maternal health services, health facilities should focus on improving the quality of care. This study assessed the satisfaction and associated factors among mothers who visited public health facilities in Adama town, Ethiopia for childbirth services. An institution based cross-sectional study design was used from June 01–30, 2018. Four hundred seventy-seven mothers participated. Three-quarters of the mothers were satisfied with the childbirth service. Age, educational status, reason for visit and wait time were found to have a significant association with satisfaction of services. The results suggest intervention is required to improve the quality of service.

Introduction

Client satisfaction of childbirth services is related to the quality of care [1]. Satisfaction is a means of preventing maternal death related to the lack of adherence to health counseling [1, 2]. Increasing satisfaction of services has long-term benefit for both the community and patients. If high quality care is provided, the utilization of reproductive and sexual health services will increase [3, 4].

Health service satisfaction is influenced by cultural beliefs, accessibility, socioeconomic status, affordability, health professionals’ approach, cleanliness of wards, and waiting rooms [4].

The health of the whole community is directly linked to the health of reproductive age women. There is a relationship between maternal and neonatal health. The immunization status, childhood development, and survival are affected by maternal health status. Healthier women and children create a better society [5,6,7]. Therefore, effective basic antenatal care, skilled birth attendance, post-partum care, and treatment of complications is essential [8, 9]. Therefore, to decrease the maternal and child mortality and morbidity, affordable, respectful and evidence-based care is necessary [10].

Satisfaction of services reflects expectations and the quality of health care received [11]. Every health professionals should work skillfully and practice with compassionate care [12, 13].

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends respectful, women-centered and evidence-based maternity practice, which improves birth outcomes. Furthermore, maintaining the highest standard of personal conduct, integrity, proper and effective communication with patients is an integral component of the health system. Therefore, incorporating these principles may improve outcomes [14, 15].

In developing countries, still, less than 50% of the mothers are satisfied with the childbirth services [3]. In urban areas of Ethiopia, the institutional delivery rate is 79%. According to the Ethiopian Ministry of Health sector transformation plan, maternal and newborn health is a priority. Respect to patient’s autonomy, dignity, feelings, and preferences is mandatory. To increase the institutional childbirth rate and promote the utilization of postnatal care, care should focus on maintaining client satisfaction [16].

Assessing satisfaction of childbirth services and health care facilities might help to guide the development and improvement of services; one way of doing this is by surveying patients who have used health services. This study tried to assess maternal satisfaction and associated factors in three public health facilities at Adama town. This information will be helpful for the health professional to improve the quality of service delivery. In addition, the study findings can help health policymakers and other sectors working on maternal health to standardize the existing interventions.

Methods

Study area, period and design

A cross-sectional study was conducted at Adama hospital and medical college, Adama health center and Geda health center in Adama, East Shewa Zone, Ethiopia. The study was conducted from June 01 to June 30, 2018.

Population

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All mothers who visited the public health hospital at Adama town for childbirth services were included, those who were critically ill were excluded.

Sample size and sampling procedure

The required sample size was determined by using a single population proportion formula with the following assumptions, 74.9% maternal satisfaction level [17] with 95% confidence interval and 4% margin of error. Adding of 10% non-response rate, the final sample size was 497.

One governmental hospital and two health centers were selected using a random sampling method, and then the sample was proportionally allocated among the health institutions. Systematic random sampling was used to select participants,. Every fourth delivering mother in the governmental hospital was included and every third delivering mother was selected in each health center.

Operational definition

Satisfaction

Those who reported being satisfied with greater or equal to 75% of items were categorized as satisfied, while those who were satisfied in less than 75% of the items were categorized as unsatisfied [8,9,10,11,12, 17, 18].

Data collection instrument and procedure

The structured questionnaire was adapted from the Donabedian quality assessment framework [18] and presented using a 5-scale likert scale (1-very dissatisfied, 2-dissatisfied, 3-neutral, 4-satisfied, and 5-very satisfied). The questionnaire was shown to be reliable in the study (Cronbach’s α = 0.725). The questionnaire sought information on the socio-demographic characteristics, obstetrics history, service characteristics and satisfaction level (Additional file 2).

Data collection was carried out in the postpartum unit. Four midwifery nurses were recruited as data collectors. One supervisor monitored the data collection. Training was provided for the data collectors and the supervisor for 2 days by the principal investigator. The training included the study objective, the meaning of each question and interviewing technique.

Data quality assurance

After completing training, data collection was piloted. During the data collection period, completeness, consistency, and accuracy of each questionnaire were reviewed. Corrective measures were taken, when necessary by the research team, to ensure a common understanding of each question. A translator was also used in some interviews.

Data processing and analysis

All data was checked manually for completeness and then coded and entered using EpiData version 3.1. Data were exported to SPSS version 20. Chi-Square was used to test a significant difference of satisfaction level among mothers who delivered in the three public health facilities. Significance was determined by using crude and adjusted odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. To assess the association between the dependent variables and independent variables, bivariate logistic regression was used. Then multivariable logistic regression was employed to identify different predictors by considering p-value less than 0.05.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics

A total of 477 women participated in the study obtaining a response rate of 96%. Of the respondents, 240(50.3%) were 25–34 years of age. Three hundred eighty-eight (81.3%) were married. Three hundred eighty-one (79.9%) attended secondary school or greater. Two hundred ten (44%) of them belong to the Oromo ethnic group and 182(10.3%) were Muslim. One hundred seven (22.4%) were government employees and 410(86%) lived in urban areas. The average monthly salary was 2265.13 Ethiopian Birr (Table 1).

Obstetrics history

One hundred eighty-five (38.8%) participants had parity of two. Regarding the reason for visit, 334(70%) of the mothers had a planned childbirth. The majority (72.1%) of women reported an unwanted pregnancy. One hundred ninety-seven (41.1%) delivered by cesarean section. Four hundred nineteen (87.8%) women did not have a delivery-related complication. Four hundred twenty-five (89.1%) women had a live born. Four hundred twenty-seven (89.5%) arrived to facility by car. The majority (93.1%) of the mothers attended antenatal care (ANC) and 354(74.2%) delivered in a health institution. One hundred twenty-seven (26.6%) were referred from another health institution (Table 2).

Satisfaction of services

Of the respondents, 162(34%), 385(80.7%), 436(91.4%), were satisfied by the health facility in regards to distance, information service, and wait time (Table 3).

Characteristics of the service delivered

461(96.6%) reported that the facility had no waiting area. Three hundred fifty-two (73.8%) had reported that the wait time was less than 1 h. Two hundred ninety-six (62.1%) received services from midwives. Two hundred eight-seven (60.2%) of them received services from male health professionals. Three hundred sixty-six (76.7%) and 393(82.4%) would like to use institutional delivery in the future and recommend institutional delivery to others, respectively (Table 4).

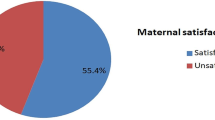

Level of satisfaction of childbirth service

Of the respondents, 357 (74.8%) and 120 (25.2%) were satisfied and unsatisfied by the services, respectively (Fig. 1). Furthermore, a significant difference was observed regarding the level of satisfaction among mothers who delivered at Adama hospital, Adama health center and Geda health center (Table 5).

Factors associated with the satisfaction on childbirth service

Age, educational status, residence, pregnancy status, mode of delivery, reason for visit and wait time were included in the final model for satisfaction of childbirth services. The multivariable logistic regression revealed that women 25–34 years (AOR; 2.026, 95%CI: 1.056, 3.887), with no formal education (AOR; 2.810, 95%CI: 1.085, 7.278), with a planned childbirth (AOR; 1.823, 95%CI: 1.024, 3.246), who encountered wait times under 1 h (AOR; 11.620, 95%CI: 3.619, 37.309) and wait times of one to 2 h (AOR; 19.620, 95%CI: 2.349, 68.500) had increased likelihood of being satisfied with childbirth services (Table 6).

Discussion

In this study, 74.8% were satisfied with the care delivered during childbirth. This finding is similar to a study conducted in Bahir Dar, which stated that 74.9% of the mothers were satisfied with their care [17]. This is lower than a report from studies conducted in Northwest Ethiopia, Southwest Ethiopia, Oromia region, west Gojjam, mid-western Nepal, and Gamo Gofa which stated that 81.7, 79.1, 80.7, 88, 89.88, 90.2% of the mothers were satisfied, respectively [19,20,21,22,23,24]. On the other hand, the finding is higher than a report from studies conducted in Addis Ababa, Amhara region, Jimma zone, and Eritrea, which stated that 19, 61.9, 65.2, and 20.8% of mothers were satisfied, respectively [25,26,27,28]. The differences might be related to the quality of services delivered at various health institutions and differing expectations. Furthermore, differences might be related to the study settings, study period or type of health institution. Dissatisfaction might be related to the fact that most women in this study had an unwanted pregnancy. In addition, the majority of the health professionals were male; however, in developing countries, most women prefer to have a care provided by women [3].

In this study, having no formal education had a positive association with satisfaction towards childbirth services. This is supported by studies conducted in mid-western Nepal [23], Gamo Gofa [24], and Ethiopia [29]. The expectation of services may be related to levels of knowledge [30]. Knowledge of the mothers is influenced by educational status [31].

Admission for a planned delivery was positively associated with satisfaction of childbirth services.

Wait times of less than 1 h or one to 2 h were positively associated with satisfaction of childbirth services. Research in South Ethiopia [24], Gamo Gofa [20] and Kenya [32] showed that mothers with less hours of waiting time had an increased satisfaction towards the childbirth service.

Mothers aged 25–34 years were two times more likely to be satisfied with childbirth services compared to those aged 35 and older. This is supported by research conducted in Jimma zone [27] and Oromia region [21]. This finding is opposite to a report from a study conducted in Bahirdar, which showed that women aged 20 to 34 years were less likely to satisfy with the care received compared to women aged 35 to 49 years [18]. In this study, most of the mothers aged 25–34 years had a complication as compared to those aged 35 and above. This might create dissatisfaction among the mothers aged 25 to 34.

The strength of the study was the involvement of three health facilities. It also used standardized measurement scale. It has to be noted that the finding of this study mainly reflects the situation in Adama town. Therefore, the findings should be interpreted with caution. The responses might be subject to social desirability bias. The factors expected to influence satisfaction of childbirth services may not be exhaustive.

Conclusion

Only three-quarters of the mothers were satisfied with the childbirth service. Age, educational status, reason for visit and wait time were found to have a significant association with the satisfaction services. This study was not able to address the perception of health professionals and this could be an area of future research. In addition, future qualitative and quantitative research could explore the mechanism required to promote the quality of childbirth services.

Availability of data and materials

The data-sets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ANC:

-

Antenatal Care

- AOR:

-

Adjusted Odds Ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- COR:

-

Crude Odds Ratio

References

Taghavi S, Ghojazadeh M, Azami-Aghdash S, Alikhah H, Bakhtiarzadeh K, Azami A, et al. Assessment of mothers’ satisfaction with the care of maternal care in specialized educational-medical centers in obstetrics and gynecological disease in northwest. Iran J Anal Res Clin Med. 2015;3(2):77–86.

Colombara DV, Hernández B, Schaefer A, Zyznieuski N, Bryant MF, Desai SS. Institutional Childbirth and Satisfaction among Indigenous and Poor Women in Guatemala, Mexico, and Panama. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(4):e0154388. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0154388.

Srivastava A, Avan BI, Preety Rajbangshi P, Bhattacharyya S. Determinants of women’s satisfaction with maternal health care: a review of literature from developing countries. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15(97). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-015-0525-0.

Takács L, Seidlerová JM, Šulová L, Hoskovcová SH. Social psychological predictors of satisfaction with intrapartum and postpartum care – what matters to women in Czech maternity hospitals? Open Med. 2015;10:119–27.

Regassa N, Bird Y, Moraros J. Preference in the use of full childhood immunizations in Ethiopia: the role of maternal health services. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2019;13:91–9.

Lassi ZS, Majeed A, Rashid S, Yakoob MY, Bhutta ZA. The interconnections between maternal and newborn health--evidence and implications for policy. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2013;26(Suppl 1):3–53. https://doi.org/10.3109/14767058.2013.784737.

Davidson PM, McGrath SJ, Meleis AI, Stern P, Digiacomo M, Dharmendra T, et al. The health of women and girls determines the health and well-being of our modern world: a white paper from the international council on Women's health issues. Health Care Women Int. 2011;32(10):870–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399332.2011.603872.

Sawyer A, Ayers S, Abbott J, Gyte G, Rabe H, Duley L. Measures of satisfaction with care during labour and birth: a comparative review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13:108 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2393/13/108.

Melese T, Gebrehiwot Y, Bisetegne D, Habte D. Assessment of client satisfaction in labor and childbirth services at a maternity referral hospital in Ethiopia. Pan Afr Med J. 2014;17(76). https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2014.17.76.3189.

Mehata S, Paudel YR, Dariang M, Aryal KK, Paudel S, Mehta R. Factors determining satisfaction among facility-based maternity clients in Nepal. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(319). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-017-1532-0.

BAZANT ES, KOENIG MA. Women’s satisfaction with childbirth care in Nairobi’s informal settlements. Int J Qual Health Care. 2009;21(2):79–86.

Wambua JM, Mbayaki R, Munyao PM, Kabue MM, Mulindi R, Change PM, et al. Client satisfaction determinants in four Kenyan slums. Int J Health Care Qual Assurance. 2015;28(7):667–77.

Marama T, Bayu H, Merga M, Binu W. Patient satisfaction and associated factors among clients admitted to obstetrics and gynecology wards of public hospitals in Mekelle town, Ethiopia: an institution-based cross-sectional study. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/2475059.

World Health Organization. WHO recommendation on respectful maternity care during labour and childbirth. https://extranet.who.int/rhl/topics/preconception-pregnancy-childbirth-and-postpartum-care/care-during-childbirth/who-recommendation-respectful-maternity-care-during-labour-and-childbirth. Accessed 10 Mar 2019.

Conesa Ferrer MB, Jordana MC, Meseguer CB, García CC, Roche MEM. Comparative study analysing women’s childbirth satisfaction and obstetric outcomes across two different models of maternity care. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e011362. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011362.

CSA and ICF International. Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey 2016: Key Indicators report. Addis Abeba and Rockville: CSA and ICF International; 2016.

Mekonnen ME, Yalew WA, Anteneh ZA. Women’s satisfaction with childbirthcare in Felege Hiwot Referral Hospital, Bahir Dar city, Northwest Ethiopia, 2014: cross sectional study. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8:528. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-015-1494-0.

Donabedian A. An introduction to quality Assurance in Health Care. USA: Oxford University Press; 2002.

Bitew K, Ayichiluhm M, Yimam K. Maternal Satisfaction on Childbirth Service and Its Associated Factors among Mothers Who Gave Birth in Public Health Facilities of Debre Markos Town, Northwest Ethiopia; 2015. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/460767.

Tesfaye R, Worku A, Godana W, Lindtjorn B. Client satisfaction with childbirth care service and associated factors in the public health facilities of Gamo Gofa zone, Southwest Ethiopia: In a Resource Limited Setting. Obstetrics and Gynecology International; 2016. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/5798068.

Amdemichael R, Tafa M, Fekadu H. Maternal Satisfaction with the Childbirth Services in Assela Hospital, Arsi Zone, Oromia Region. Gynecol Obstet (Sunnyvale). 4:257. https://doi.org/10.4172/2161-0932.1000257.

Asres GD. Satisfaction and associated factors among mothers delivered at Asrade Zewude memorial primary hospital, Bure, west Gojjam, Amhara, Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. J Public Manag Res. 2018;4(1):14–28.

Panth A, Kafle P. Maternal satisfaction on childbirth service among postnatal mothers in a government hospital, Mid-Western Nepal. Obstetrics and Gynecology International. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/4530161.

Dewana Z, Fikadu T, Mariam AG, Abdulahi M. Client perspective assessment of women’s satisfaction towards labour and childbirth care service in public health facilities at Arba Minch town and the surrounding district, Gamo Gofa zone, south Ethiopia. Reproductive Health. 2016;13(11). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-016-0125-0.

Demas T, Getinet T, Bekele D, Gishu T, Birara M, Abeje Y. Women’s satisfaction with intrapartum care in St Paul’s Hospital Millennium Medical College Addis Ababa Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(253). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-017-1428-z.

Tayelgn A, Zegeye DT, Kebede Y. Mothers’ satisfaction with referral hospital childbirth service in Amhara Region, Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2011;11(78) http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2393/11/78.

Tadesse BH, Bayou NB, Nebeb GT. Mothers’ satisfaction with institutional childbirth Service in Public Health Facilities of Omo Nada District, Jimma Zone. Clin Med Res. 2017;6(1):23–30.

Kifle MM, Ghirmai FA, Berhe SA, Tesfay WS, Weldegebrie YT, Gebrehiwet ZT. Predictors of Women’s satisfaction with hospital-based Intrapartum Care in Asmara Public Hospitals. Eritrea Obstetrics Gynecology Int. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/3717408.

Agumasie M, Yohannes Z, Abegaz T. Maternal Satisfaction and Associated Factors on Childbirth Care Service in Hawassa City Public Hospitals, South Ethiopia. Gynecol Obstet (Sunnyvale). 2018;8(473). https://doi.org/10.4172/2161-0932.1000473(2018.

Gashaye KT, Tsegaye AT, Shiferaw G, Worku AG, Abebe SM. Client satisfaction with existing labor and delivery care and associated factors among mothers who gave birth in university of Gondar teaching hospital; Northwest Ethiopia: institution based cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2019;14(2):e0210693. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0210693.

Adegbosin AE, Zhou H, Wang S, Stantic B, Sun J. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between dimensions of inequality and a selection of indicators of reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health (RMNCH). J Glob Health. 2019 Jun;9(1):010429. https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.09.010429.

Gitobu CM, Gichangi PB, Mwanda WO. Satisfaction with childbirth services offered under the free maternal healthcare policy in Kenyan public health facilities. J Environ Public Health. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/4902864.

Acknowledgements

We would like to forward our deepest appreciation to the Adama General Hospital and Medical College for their cooperation on necessary materials and supports to undertake this study. Finally, our appreciation also goes to the data collectors, supervisors and mothers who participated in the study.

Funding

No funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MT, DB, ROF and MSO conceptualized and designed the study, analyzed, interpreted the data, drafted the manuscript and critically reviewed the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical clearance letter obtained from Research and Ethics Committee of Adama Hospital and Medical College. The Ethics Committee approved obtaining the verbal consent. The letter was submitted to the three health facilities and permission obtained. Additionally an informed verbal consent obtained from each respondent after providing sufficient information regarding the purpose of study and the right to refuse participation or jump some questions unwilling to answer. To ensure the confidentiality, name of respondents’ was not written on the questionnaires.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.

Conceptual Framework

Additional file 2.

Questionnaire

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Tadele, M., Bikila, D., Fite, R.O. et al. Maternal satisfaction towards childbirth Service in Public Health Facilities at Adama town, Ethiopia. Reprod Health 17, 60 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-020-00911-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-020-00911-0