Abstract

Background

Raynaud’s phenomenon (RP) is a functional vascular disease, presenting with recurrent episodes of ischemia of extremities in response to cold and emotional stress. Investigating cutaneous microcirculation is an important tool in understanding the complex neuro-immuno-vascular interactions in its pathophysiological mechanisms. Since there is no available data on vascular responsiveness in RP in the paediatric population, we investigated skin perfusion and heat-induced hyperaemia in comparison with clinical severity and laboratory parameters of the disease.

Methods

Fifty two adolescents (27 patients with primary RP and 25 age-matched healthy controls) were investigated in the study. Patients were divided into two groups according to the symptoms existing within the previous 2 months. Following baseline microcirculation measurement with Laser Doppler flowmetry (Periflux 5000 system), all subjects underwent local heating test at 42 °C and 44 °C. Besides routine laboratory parameters, immune-serological tests and the vasoactive sensory neuropeptides somatostatin and pituitary adenylate-cyclase activating polypeptide (PACAP) were measured.

Results

Baseline perfusion measured in perfusion units (PU) at 32 °C was significantly lower in symptomatic RP patients (97.6 ± 22.4 PU) compared with both healthy volunteers (248.3 ± 23.5 PU, p < 0.001) and RP patients without symptoms (187.4 ± 24.9 PU, p < 0.05). After local heating to 42 °C maximum blood flow was significantly reduced in primary RP participants with current symptoms (358.6 ± 43.9 PU, p < 0.001), but not in asymptomatic ones (482.3 ± 28.7 PU, p > 0.05) when compared with healthy subjects (555.9 ± 28.2 PU). Both the area under the response curve and the latency to reach the maximum flow were significantly increased in both RP groups (symptomatic 164.6 ± 7.4 s, p < 0.001, asymptomatic 236.4 ± 17.4 s, p < 0.001) when compared with the control group (101.9 ± 4.7 s). The heat-induced percentage increase from baseline to maximal blood flow was significantly greater in symptomatic RP adolescents in comparison with healthy ones. Laboratory parameters and neuropeptide plasma levels were not altered in any groups.

Conclusion

To our knowledge this is the first study in paediatric population to show altered heat-induced cutaneous hyperaemia responses in relation with the clinical severity and symptomatology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Raynaud phenomenon (RP), first described by Maurice Raynaud in 1862 [1], is defined as recurrent, reversible episodes of vasospasm involving peripheral small vessels. The fingers are the most commonly affected regions and RP is typically triggered by cold exposure, emotional stress and exercise [2]. The phenomenon is manifested clinically by sharply demarcated colour changes of the skin of the digits, and can be classified as primary and secondary. Primary RP accounting for 80% of the cases is present without any associated diseases explaining the symptoms [3]. Secondary RP is associated with other conditions, mainly connective tissue diseases (CTD), endocrine and hyperviscosity disorders, as well as drug exposure. It commonly occurs (80–90%) in children with systemic sclerosis (SSc) and CTD. The differentiation between the two forms is important, because primary RP has good outcome, but careful monitoring is essential to ensure early detection and management of evolving CTD [4,5,6].

The prevalence of RP is more common among women and family members of RP patients [7], it is approximately 3–20% in the total population [2, 3, 8]. However, the pediatric prevalence is not well known. A study of 720 school-children at the age of 12–15 years in the UK reported a prevalence of 18% in females and 12% of males [9].

Cutaneous blood flow is regulated by complex neuro-immune-humoral mechanisms, involving both the autonomic and sensory nervous systems. Mediators are hormones and vasoactive compounds released from nerves, circulating cells and blood vessels. The pathophysiology of RP is poorly understood, but the key mechanism is related to the imbalance between vasoconstrictor and vasodilator events. A complex disorder of several neuroendocrine interactions and local production of reactive oxygen species resulting in decreased nitric oxide (NO) production lead to intensified vasoconstriction [8, 10,11,12,13]. Sensory nerves play a predominant role in the regulation of vascular responses elicited by thermal stimuli. Peptide mediators released from autonomic or sensory nerve endings, such as calcitonin gene related peptide (CGRP) [14], vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) or the closely related pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide (PACAP) [15, 16] dilate the vessels by directly relaxing the vascular smooth muscle and indirectly via the endothelial release of NO [12]. Indeed, reduction of CGRP- and VIP-positive nerves in the skin of adult RP patients has been described [17, 18]. On the other hand, it is well known that secondary RP in SSc is also caused by structural microvascular changes, such as endothelial dysfunction and fibrous intimal proliferation with associated intravascular thrombi [19].

In order to get closer to the pathophysiological mechanisms, it is important to investigate cutaneous microvascular function in RP. Skin microcirculation can be examined by both non-invasive [20,21,22] and invasive techniques, such as biopsies [17] or intradermal delivery of drugs [23]. Laser Doppler flowmetry is a sensitive, non-invasive method for the measurement of tissue perfusion. The monochromatic laser beam penetrates the skin, it is reflected depending on the movement velocity of the red blood cells and recorded by a sensitive sensor. Cold stimulation-induced skin blood flow responses were found to be unaltered in adult RP and SSc patients, as compared to healthy subjects [24]. Meanwhile, several other studies in adults showed a dramatic alteration of the amplitude and the kinetics of post-occlusive hyperaemia in patient with SSc compared to primary RP and healthy controls [25, 26]. However, thermal hyperaemia was more sensitive and specific than post-occlusive hyperaemia for differentiating SSc from primary RP [27]. All these data clearly show that investigating vascular responsiveness in the skin, with special emphasis on heat-induced vasodilatation is a valuable tool to understand the pathophysiological background of RP, but there are no data in paediatric population.

Therefore, the aim of the present study was to investigate cutaneous microcirculatory alterations in RP adolescents and analyse the heat-induced microvascular responsiveness in relation to the clinical symptoms.

Methods

Patient selection and ethics

Fifty-two adolescents were enrolled in this study at the Department of Pediatrics of the Clinical Centre of the University of Pécs, Hungary in March and April of 2015.

Primary RP was diagnosed according to the criteria of LeRoy [28], including a normal nail-fold capillaroscopy (characterized by homogeneous distribution of capillary loops similar in shape and size), the lack of antinuclear antibodies, no digital pitting scar and the lack of clinical symptoms of CTD. Exclusion criteria were cigarette smoking, chronic diseases such as CTD, diabetes mellitus, hypercholesterolemia, hypertonia and any drug therapy. Two eligible RP participants were later also excluded from the study due to difficulties with the microcirculation measurement analysis.

Healthy adolescents were recruited through letters sent to the local secondary schools. Overall, there were 27 patients with primary Raynaud syndrome and 25 age- and gender-matched healthy controls.

The study was performed according to the recommendations of the Declaration of Helsinki and the protocol was approved by the Local Ethics Committee (5501/2015). Informed consent was obtained from all adolescents and their parents.

Measurement protocol and paradigm

On the day of the investigation, the participants arrived at the department between 7:30 a.m. and 9 a.m. in the fasting state. Measurements were performed within one day in a quiet room at 23.0 ± 0.5 °C temperature. After a thorough physical examination, body composition analysis was done with Tanita BC 420 MA Body Composition Analyser [29]. Afterwards, subjects were placed in a supine position with both forearms resting at heart level. Five minutes later, heart rate and blood pressure were measured.

Venous blood samples were taken for routine laboratory tests including haematocrit (Htc), haemoglobin (Hgb), white blood cell count (WBC), platelet count, differential blood smear, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C- reactive protein (CRP), liver and kidney function, thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), coagulation tests, immunoglobulin and complements (C3,C4). Immunoserological tests included the measurements of antinuclear (ANA), anti-dsDNA, anti-centromere (ACA), anti-C1Q, anti-extractable nuclear antibody (ENA), anticardiolipin and anti-beta 2 glycoprotein, antiprothrombin antibody levels. Routine urine analysis was also performed. Blood samples were also collected for measuring vasoactive sensory neuropeptides, such as PACAP-38 and somatostatin by specific and sensitive radioimmunoassay (RIA) techniques developed in our laboratory [30, 31]. Peptidase inhibitor aprotinin (200 IU per ml of blood; Gordox, Gedeon Richter, Budapest) was added immediately to the blood taken into EDTA tubes. Plasma was obtained by centrifugation of whole blood at 4 °C degree 1000 g for 4 min and then 4000 g for 15 min and aliquots were stored at −70 °C.

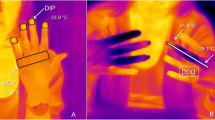

The participants were resting comfortably for 5 min and their arms were immobilised to ensure stable positioning. Microcirculation on the left index finger was measured with the Periflux 5000 system (Perimed AB, Stockholm, Sweden) Laser Doppler technology. A thermostatic Laser Doppler probe (Probe 457) was placed on the distal phalanx of the second finger of the left hand. Data from the Laser Doppler flowmeter were interfaced to a computer, the perfusion measured in arbitrary perfusion units (PU) and the kinetics of the response was determined by the time. Baseline mean temperature was maintained at 32 °C and blood flow recorded over 5 min. The laser probe was heated to 42 °C for 10 min and then 44 °C for a period of maximum 5 min. Microcirculation parameters, such as heat-induced hyperaemia were expressed as the area under the response curve (AUC), time to peak response (the time to attain maximal cutaneous perfusion in seconds), peak perfusion value and percentage increase (Fig. 1). The cooling test could not be performed because of the symptoms of RP patients.

Data analysis and statistics

Data management and analysis were performed using GraphPad Prism version 5.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Values were expressed as means ± SEM in all the 3 groups of subjects. The normal distribution of investigated parameters was confirmed by D’Agostino-Pearson and Shapiro-Wilk normality tests. In case of normal distribution, values for each group were compared by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Newman-Keuls multiple comparison test. Otherwise, the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison test was used for statistical analysis. A value of p < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. Correlation coefficients between selected clinical and microcirculation parameters were also analysed.

Results

Clinical and laboratory characteristics of the patients

The demographics and clinical characteristics of the 52 adolescents investigated in the study are listed in Table 1. Patients with Raynaud symptoms were divided into two groups according to the symptoms existing on the day of the study or in the past 2 months. Four of the participants included in the control group were diagnosed based on medical history and physical examination with primary RP and were therefore switched to the group of Raynaud patients without current symptoms. Only one of the patients without current symptoms of RP had Tanner stage III, all the rest had Tanner stage IV.

Most patients except one in each group among the Raynaud patients were girls. The mean duration of primary RP was 23.2 ± 4.9 months in the group of Raynaud without symptoms and 38.4 ± 6.9 months in the group of Raynaud with symptoms, the difference, however, was not statistically significant. Compared to healthy controls body fat percentage values were significantly higher in Raynaud children without symptoms and significantly lower in symptomatic patients compared to controls. BMI was also significantly lower in symptomatic patients compared to either healthy controls or patients with symptoms. In the group of RP with symptoms 1 person was found to be severely underweight, and 3 were underweight but none of the patients were anorectic. At the same time in the group of RP without symptoms only one patient was underweight, however four of them were obese. The difference in BMI was highly significant between the two patient groups, as well.

The mean arterial blood pressure was also lower in Raynaud patients with symptoms compared with either healthy or asymptomatic patients (Table 1). Participants were asked to rate their symptoms based on numbness, pain, and the frequency and duration of attacks. Patient-reported subjective symptom severity was moderate to severe. Ischemic ulcerations were not observed in any cases at the time of the study. The history and clinical examination did not show any signs of CTD. The laboratory parameters were in the normal range in all subjects. None of them had positive autoantibodies against nuclear (ANA), topoisomerase I (SCL-70) or centromere-associated (ACA) proteins.

Nail-fold capillaroscopy did not show scleroderma pattern characterized by enlarged capillaries, giant capillaries, haemorrhages, or loss of capillaries, disorganization of capillaries architecture in any of the subjects. We only found non-specific patterns, minor capillary morphological changes (mean disarrangement of capillary density and capillary polarity, nonhomogeneous distribution or size of loops, linear elongation of the loop) which can even be found in primary RP patients and they are not considered pathological.

Disease activity-relation of microcirculatory impairment in adolescents with Raynaud phenomenon

Baseline perfusion at 32 °C was 97.6 ± 22.4 perfusion units (PU) in symptomatic Raynaud patients which was significantly lower compared with either healthy volunteers (248.3 ± 23.5 PU, p < 0.001) or patients without symptoms (187.4 ± 27.9 PU, p < 0.05). The difference between healthy controls and asymptomatic participants was not statistically significant. (Fig. 2a). Heating to 42 °C and 44 °C induced a gradual increase in cutaneous blood flow. The maximum blood flow at 42 °C was significantly reduced in RP adolescents with current symptoms (358.6 ± 43.9 PU), compared with healthy subjects (555.9 ± 8.2 PU, p < 0.05). However, there was no significant difference in this response parameter between healthy controls and patients without symptoms (482.3 ± 28.7 PU) or between the two Raynaud groups (Fig. 2b). Analysing the percentage changes from baseline to maximal flow during heating to 42 °C, significantly greater increase was detected in symptomatic RP adolescents (452.9 ± 93.4%) compared with either the controls (185.1 ± 42.5%, p < 0.01), or the asymptomatic RP patients (241.7 ± 61.5%, p < 0.05). This parameter did not differ in the disease group without symptoms in comparison with healthy subjects, similarly to the absolute perfusion values (Fig. 2c). Heating to 44 °C induced perfusion changes similar to the 42 °C stimulus and statistical comparisons revealed the same differences between groups (Fig. 2b and c).

Baseline perfusion (a) demonstrated as perfusion units (PU), maximum perfusion in response to heating to 42 °C and 44 °C (b), percentage perfusion increase during heating (c). Columns represent the means±SEM of each group (*p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; one-way ANOVA followed by Neuman-Keuls multiple comparison test)

Additional analysis of the perfusion change revealed that the kinetics of the heat-induced response was also altered in patients with RP in comparison with healthy controls. The AUC of the 42 °C heat-induced perfusion response was significantly greater in both Raynaud disease groups compared with the control group. No significant difference in AUC was found between symptomatic and asymptomatic patients (Fig. 3a).

On the other hand, latency to reach the maximum perfusion at 42 °C was significantly longer in both patient groups (symptomatic: 236.4 ± 17.4 s, asymptomatic 164.6 ± 7.4 s) compared with healthy controls (101.9 ± 4.7 s, p < 0.001 for both). Moreover, the latency was also significantly different between the two RP patient groups (p < 0.001, Fig. 3b).

Correlations between microcirculatory parameters and mean blood pressure or body fat percentage or disease duration were analysed, but no significant relationships were detected (data not shown).

Plasma concentrations of vasoactive sensory neuropeptides were not altered in primary Raynaud adolescents. PACAP-38 and somatostatin-LI were reliably measurable in the systemic circulation, however there were no significant differences between their concentrations in the three groups (Table 2.).

Discussion

To our knowledge this is the first study in a paediatric primary RP population to show altered heat-induced cutaneous hyperaemia responses in relation with the clinical severity and symptomatology.

Detection of tissue perfusion dysfunction is necessary for the early diagnosis of microvascular disease. Laser Doppler flowmetry has been proven to be a valuable non-invasive method for the diagnosis and follow-up of peripheral vascular diseases such as diabetic microangiopathy, atherosclerosis, and wound healing after burns or reconstructive surgery [32,33,34,35]. Since baseline perfusion values depend on a variety of exogenous and endogenous factors, the results of provocation tests (pressure, heat, cold or chemical stimulation) should be used for reliable comparison. Local heat-induced skin hyperaemia is based on two separate mechanisms: a sensory nerve-mediated initial peak and a sustained plateau phase dependent on endothelial factors, mostly NO [36, 37]. Previous studies in the adult primary RP population showed that the initial neurogenic vasodilator response to heating was not affected by the disease [27, 38]. Few capillary microscopy studies have investigated the vasculature in RP children, but none of them described functional investigations of responsiveness to heat [39, 40].

Similarly to previous adult studies we also found significantly decreased baseline blood flow in primary RP adolescents, but only in the symptomatic group [41, 42]. This can be partially explained by the higher body weight and fat percentage in the population of asymptomatic RP, since BMI has an impact on the regulation of skin temperature and perfusion. It has been demonstrated that weight could have an impact on sympathetic nerve–dependent regulation of vascular tone [43] and studies in obese children also reported increased skin perfusion [44, 45]. Furthermore, BMI was shown to be related to skin temperature and skin perfusion in adult patients with primary RP, but not in healthy controls [46].

We showed that both the kinetics and amplitude of the hyperaemic response to local heating were altered in RP in comparison with healthy participants. It should be emphasized that the kinetics of the thermal response could distinguish between symptomatic and asymptomatic RP children. Peak perfusion values during heating were significantly lower and responses were significantly delayed in symptomatic primary RP adolescents. These findings are fundamentally different from the results reported in adult primary RP patients [27]. Unexpectedly, the percentage increase above baseline, as well as the AUC values were significantly higher in the symptomatic group compared to healthy controls. It might suggest a functional reserve capacity of the microvasculature in these patients. The higher relative increase might be explained by a greater sensitivity of RP patients to intravenous CGRP, as described in adults [47], although this finding was not confirmed by others [48, 49]. In contrast, no difference was observed in the maximum perfusion or in the percentage increase between asymptomatic RP patients and controls. However, the AUC and latency to reach the maximum perfusion were significantly higher, demonstrating an overall difference between asymptomatic primary RP and healthy adolescents. The most sensitive parameter proved to be the latency value, since it could differentiate between the three study groups. In adults the response to local heating was described as a characteristic to distinguish secondary RP patients from primary ones [27], but to our knowledge, ours were the first to use Laser Doppler flowmetry as a tool to detect the disease severity in the paediatric RP population.

A complex interplay of several neuroendocrine mechanisms with local pathways is present in RP and CTD. The pathophysiology of primary RP is multifactorial with both vascular and neural abnormalities. The loss of CGRP- and VIP-containing nerves in the cutaneous microvasculature [17, 18] and abnormal response of cold-sensitive nerves were described in primary adult RP patients [50]. A recent study found a strong relationship between microangiopathy and higher serum endothelin-1 and E-selectin levels in children with RP [40], although previous data had not confirmed the diagnostic value of endothelin concentration [51]. It is well-established that peptide mediators play a role in neurovascular responses, but there is limited data about neuropeptide concentration changes in primary RP [12]. We found no plasma concentration alterations of vasoactive sensory neuropeptides in primary RP adolescents compared with healthy controls. The lack of systemic changes of neuropeptide levels suggests that only local neuroendocrine mechanism may be involved in a shift towards vasoconstriction.

Some potential limitations should be considered when interpreting our results. First, it was a monocentric study. The number of participants was small, but we strictly compared age and sex-matched groups to avoid possible bias in pubertal development. In order to minimize a possible bias by differences in physical examination and microcirculation measurement with Laser Doppler flowmetry, the same investigator did the procedure. A disadvantage of Laser Doppler flowmetry is the dependence of the signal of other variables such as skin thickness or temperature. Therefore, care was taken to perform perfusion measurements at the same site under standardized, identical conditions and a preheated probe was used to standardize baseline cutaneous temperature. Despite these limitations, assessment of perfusion changes by Laser Doppler flowmetry is considered accurate and reliable for diagnostic purposes of peripheral arterial disease [52, 53].

Conclusion

To our knowledge, this is the first study in paediatric RP population to show altered heat-induced cutaneous hyperaemia responses in relation to the clinical severity and symptomatology using a sensitive, easy and non-invasive method. Since CTD develop in 3–40% of RP subjects [4,5,6], early detection is important for better treatment results and prognosis. Previous studies suggest that in CTD microcirculatory changes develop before morphological abnormalities are seen with nail-fold capillaroscopy [54,55,56]. Therefore, altered microvascular response to thermal stimuli could be an early marker, but a follow-up study is needed to determine whether this parameter could be an objective severity and prognosis indicator.

Abbreviations

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

- CGRP:

-

Calcitonin gene-related peptide

- CTD:

-

Connective tissue disease

- NO:

-

Nitric oxide

- PACAP:

-

Pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide

- RP:

-

Raynaud phenomenon

- SOM:

-

Somatostatin

- SSc:

-

Systemic sclerosis

References

Raynaud M. De l’asphyxie locale et de la gangrène symétrique des extrémités. Leclerc L, editor. Paris: Rignoux; 1862.

Herrick AL. The pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment of Raynaud phenomenon. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2012;8:469–79.

Wigley FM. Clinical practice. Raynaud’s phenomenon. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1001–8.

Hirschl M, Hirschl K, Lenz M, Katzenschlager R, Hutter H-P, Kundi M. Transition from primary Raynaud’s phenomenon to secondary Raynaud’s phenomenon identified by diagnosis of an associated disease: results of ten years of prospective surveillance. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:1974–81.

Koenig M, Joyal F, Fritzler MJ, Roussin A, Abrahamowicz M, Boire G, et al. Autoantibodies and microvascular damage are independent predictive factors for the progression of Raynaud’s phenomenon to systemic sclerosis: a twenty-year prospective study of 586 patients, with validation of proposed criteria for early systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(12):3902.

Pavlov-Dolijanovic S, Damjanov NS, Stojanovic RM, Vujasinovic Stupar NZ, Stanisavljevic DM. Scleroderma pattern of nailfold capillary changes as predictive value for the development of a connective tissue disease: a follow-up study of 3,029 patients with primary Raynaud’s phenomenon. Rheumatol Int. 2012;32:3039–45.

Suter LG, Murabito JM, Felson DT, Fraenkel L. The incidence and natural history of Raynaud’s phenomenon in the community. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:1259–63.

Herrick AL. Pathogenesis of Raynaud’s phenomenon. Rheumatol Oxf Engl. 2005;44:587–96.

Jones GT, Herrick AL, Woodham SE, Baildam EM, Macfarlane GJ, Silman AJ. Occurrence of Raynaud’s phenomenon in children ages 12-15 years: prevalence and association with other common symptoms. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:3518–21.

Cooke JP, Marshall JM. Mechanisms of Raynaud’s disease. Vasc Med. 2005;10:293–307.

Furspan PB, Chatterjee S, Freedman RR. Increased tyrosine phosphorylation mediates the cooling-induced contraction and increased vascular reactivity of Raynaud’s disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:1578–85.

Fonseca C, Abraham D, Ponticos M. Neuronal regulators and vascular dysfunction in Raynaud’s phenomenon and systemic sclerosis. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2009;7:34–9.

Flavahan NA. Pathophysiological Regulation of the Cutaneous Vascular System in Raynaud’s Phenomenon. In: Wigley FM, Herrick AL, Flavahan NA, editors. Raynaud’s Phenom. New York, NY: Springer; 2015. p. 57–79. [cited 2017 Jul 9] Available from: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-1-4939-1526-2_5.

Russell FA, King R, Smillie S-J, Kodji X, Brain SD. Calcitonin gene-related peptide: physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol Rev. 2014;94:1099–142.

Vaudry D, Gonzalez BJ, Basille M, Yon L, Fournier A, Vaudry H. Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide and its receptors: from structure to functions. Pharmacol Rev. 2000;52:269–324.

Kellogg DL, Zhao JL, Wu Y, Johnson JM. VIP/PACAP receptor mediation of cutaneous active vasodilation during heat stress in humans. J Appl Physiol. 2010;109:95–100.

Bunker CB, Terenghi G, Springall DR, Polak JM, Dowd PM. Deficiency of calcitonin gene-related peptide in Raynaud’s phenomenon. Lancet Lond Engl. 1990;336:1530–3.

Terenghi G, Bunker CB, Liu YF, Springall DR, Cowen T, Dowd PM, et al. Image analysis quantification of peptide-immunoreactive nerves in the skin of patients with Raynaud’s phenomenon and systemic sclerosis. J Pathol. 1991;164:245–52.

Wigley FM. Vascular disease in scleroderma. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2009;36:150–75.

Picart C, Carpentier PH, Brasseur S, Galliard H, Piau JM. Systemic sclerosis: blood rheometry and laser Doppler imaging of digital cutaneous microcirculation during local cold exposure. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 1998;18:47–58.

Mahé G, Humeau-Heurtier A, Durand S, Leftheriotis G, Abraham P. Assessment of skin microvascular function and dysfunction with laser speckle contrast imaging. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;5:155–63.

Keymel S, Sichwardt J, Balzer J, Stegemann E, Rassaf T, Kleinbongard P, et al. Characterization of the non-invasive assessment of the cutaneous microcirculation by laser Doppler perfusion scanner. Microcirc N Y N 1994. 2010;17:358–66.

Cracowski J-L, Minson CT, Salvat-Melis M, Halliwill JR. Methodological issues in the assessment of skin microvascular endothelial function in humans. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2006;27:503–8.

Creutzig A, Hiller S, Appiah R, Thum J, Caspary L. Nailfold capillaroscopy and laser Doppler fluxmetry for evaluation of Raynaud’s phenomenon: how valid is the local cooling test? Vasa Z Gefasskrankheiten. 1997;26:205–9.

Wigley FM, Wise RA, Mikdashi J, Schaefer S, Spence RJ. The post-occlusive hyperemic response in patients with systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33:1620–5.

Gaillard-Bigot F, Roustit M, Blaise S, Gabin M, Cracowski C, Seinturier C, et al. Abnormal amplitude and kinetics of digital postocclusive reactive hyperemia in systemic sclerosis. Microvasc Res. 2014;94:90–5.

Boignard A, Salvat-Melis M, Carpentier PH, Minson CT, Grange L, Duc C, et al. Local hyperhemia to heating is impaired in secondary Raynaud’s phenomenon. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7:R1103.

LeRoy EC, Medsger TA. Raynaud’s phenomenon: a proposal for classification. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1992;10:485–8.

Lloret Linares C, Ciangura C, Bouillot J-L, Coupaye M, Declèves X, Poitou C, et al. Validity of leg-to-leg bioelectrical impedance analysis to estimate body fat in obesity. Obes Surg. 2011;21:917–23.

Sütő B, Bagoly T, Börzsei R, Lengl O, Szolcsányi J, Németh T, et al. Surgery and sepsis increase somatostatin-like immunoreactivity in the human plasma. Peptides. 2010;31:1208–12.

Tuka B, Helyes Z, Markovics A, Bagoly T, Szolcsányi J, Szabó N, et al. Alterations in PACAP-38-like immunoreactivity in the plasma during ictal and interictal periods of migraine patients. Cephalalgia Int J Headache. 2013;33:1085–95.

Roustit M, Maggi F, Isnard S, Hellmann M, Bakken B, Cracowski J-L. Reproducibility of a local cooling test to assess microvascular function in human skin. Microvasc Res. 2010;79:34–9.

Jaskille AD, Ramella-Roman JC, Shupp JW, Jordan MH, Jeng JC. Critical review of burn depth assessment techniques: part II. Review of laser doppler technology. J Burn Care Res Off Publ Am Burn Assoc. 2010;31:151–7.

Skrha J, Prázný M, Haas T, Kvasnicka J, Kalvodová B. Comparison of laser-Doppler flowmetry with biochemical indicators of endothelial dysfunction related to early microangiopathy in type 1 diabetic patients. J Diabetes Complicat. 2001;15:234–40.

Hu C-L, Lin Z-S, Chen Y-Y, Lin Y-H, Lai M-F, Li M-L. Application of the laser Doppler flowmeter for measurement of blood pressure and functional parameters of microcirculation. Biomed Mater Eng. 2012;22:351–9.

Minson CT, Berry LT, Joyner MJ. Nitric oxide and neurally mediated regulation of skin blood flow during local heating. J Appl Physiol Bethesda Md 1985. 2001;91:1619–26.

Johnson JM, Minson CT, Kellogg DL. Cutaneous vasodilator and vasoconstrictor mechanisms in temperature regulation. Compr Physiol. 2014;4:33–89.

Roustit M, Simmons GH, Carpentier P, Cracowski JL. Abnormal digital neurovascular response to local heating in systemic sclerosis. Rheumatol Oxf Engl. 2008;47:860–4.

Jayanetti S, Smith CP, Moore T, Jayson MI, Herrick AL. Thermography and nailfold capillaroscopy as noninvasive measures of circulation in children with Raynaud’s phenomenon. J Rheumatol. 1998;25:997–9.

Latuskiewicz-Potemska J, Chmura-Skirlinska A, Gurbiel RJ, Smolewska E. Nailfold capillaroscopy assessment of microcirculation abnormalities and endothelial dysfunction in children with primary or secondary Raynaud syndrome. Clin Rheumatol. 2016;35:1993–2001.

Greenstein D, Gupta NK, Martin P, Walker DR, Kester RC. Impaired thermoregulation in Raynaud’s phenomenon. Angiology. 1995;46:603–11.

Roustit M, Simmons GH, Baguet J-P, Carpentier P, Cracowski J-L. Discrepancy between simultaneous digital skin microvascular and brachial artery macrovascular post-occlusive hyperemia in systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol. 2008;35:1576–83.

Bemelmans RHH, van der Graaf Y, Nathoe HM, Wassink AMJ, Vernooij JWP, Spiering W, et al. Increased visceral adipose tissue is associated with increased resting heart rate in patients with manifest vascular disease. Obes Silver Spring Md. 2012;20:834–41.

Chin LC, Huang TY, Yu CL, Wu CH, Hsu CC, Yu HS. Increased cutaneous blood flow but impaired post-ischemic response of nutritional flow in obese children. Atherosclerosis. 1999;146:179–85.

Schlager O, Willfort-Ehringer A, Hammer A, Steiner S, Fritsch M, Giurgea A, et al. Microvascular function is impaired in children with morbid obesity. Vasc Med Lond Engl. 2011;16:97–102.

Giurgea G-A, Mlekusch W, Charwat-Resl S, Mueller M, Hammer A, Gschwandtner ME, et al. Relationship of age and body mass index to skin temperature and skin perfusion in primary Raynaud’s phenomenon. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67:238–42.

Shawket S, Hazleman B, Dickerson C, Brown MJ. Selective suprasensitivity to calcitonin-gene-related peptide in the hands in Raynaud’s phenomenon. Lancet. 1989;334:1354–7.

Brain SD, Petty RG, Lewis JD, Williams TJ. Cutaneous blood flow responses in the forearms of Raynaud’s patients induced by local cooling and intradermal injections of CGRP and histamine. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1990;30:853–9.

Bunker CB, Foreman JC, Dowd PM. Digital cutaneous vascular responses to histamine and neuropeptides in Raynaud’s phenomenon. J Invest Dermatol. 1991;96:314–7.

Roustit M, Blaise S, Millet C, Cracowski J-L. Impaired transient vasodilation and increased vasoconstriction to digital local cooling in primary Raynaud’s phenomenon. AJP Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;301:H324–30.

Biernacka-Zielinska M, Brozik H, Smolewska E, Mikinka M, Jakubowska T, Stanczyk J. Diagnostic value of thermography and endothelin concentration in serum of children with Raynaud’s syndrome. Med Wieku Rozwoj. 2005;9:213–22.

Høyer C, Sandermann J, Paludan JPD, Pavar S, Petersen LJ. Diagnostic accuracy of laser Doppler flowmetry versus strain gauge plethysmography for segmental pressure measurement. J Vasc Surg. 2013;58:1563–70.

Høyer C, Paludan JPD, Pavar S, Biurrun Manresa JA, Petersen LJ. Reliability of laser Doppler Flowmetry curve reading for measurement of toe and ankle pressures: intra- and inter-observer variation. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2014;47:311–8.

Binaghi F, Cannas F, Mathieu A, Pitzus F. Correlations among capillaroscopic abnormalities, digital flow and immunologic findings in patients with isolated Raynaud’s phenomenon. Can laser Doppler flowmetry help identify a secondary Raynaud phenomenon? Int Angiol J Int Union Angiol. 1992;11:186–94.

Murray AK, Moore TL, Manning JB, Taylor C, Griffiths CEM, Herrick AL. Noninvasive imaging techniques in the assessment of scleroderma spectrum disorders. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:1103–11.

Correa MJ, Andrade LE, Kayser C. Comparison of laser Doppler imaging, fingertip lacticemy test, and nailfold capillaroscopy for assessment of digital microcirculation in systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12:R157.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Teréz Bagoly for performing the radioimmunoassay for neuropeptide level measurement.

This work is dedicated to the 650th anniversary of the University of Pécs.

Funding

This work was supported by National Brain Research Program 20017-1.2.1-NKP -2017-00002, “Stay Alive” GINOP-2.3.2.-15-2016-00048 and EFOP-3.6.1-16-2016-00004 grants.

Availability of data and materials

Please contact author for data requests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BM participated in the diagnosis and treatment of the patients, BM, KB, ZH participated in the perfusion measurements and in the analysis of data. BM, KB, ZH drafted the manuscript. ZH and KB supervised the work. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by The Regional Research Ethics Committee of the Medical Center, University of Pécs (5501/2015). Written informed consents were obtained from the adolescents and their parents for the participation.

Consent for publication

Written informed consents were obtained from the patients’ parents for publication of this study.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Mosdósi, B., Bölcskei, K. & Helyes, Z. Impairment of microcirculation and vascular responsiveness in adolescents with primary Raynaud phenomenon. Pediatr Rheumatol 16, 20 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12969-018-0237-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12969-018-0237-x