Abstract

Background

Plexiform fibromyxoma (PF) is a rare gastric tumor often confused with gastrointestinal stromal tumor. These so-called “benign” tumors often present with upper GI bleeding and gastric outlet obstruction. It was recently demonstrated that approximately one-third of PF have activation of the GLI1 oncogene, a transcription factor in the hedgehog (Hh) pathway, via a MALAT1-GLI1 fusion protein or GLI1 up-regulation. Despite this discovery, the biology of most PFs remains unknown.

Methods

Next generation sequencing (NGS) was performed on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples of PF specimens collected from three institutions (UCSD, NCI and OHSU). Fresh frozen tissue from one tumor was utilized for in vitro assays, including quantitative RT-PCR and cell viability assays following drug treatment.

Results

Eight patients with PF were identified and 5 patients’ tumors were analyzed by NGS. An index case had a mono-allelic PTCH1 deletion of exons 15–24 and a second case, identified in a validation cohort, also had a PTCH1 gene loss associated with a suspected long-range chromosome 9 deletion. Building on the role of Hh signaling in PF, PTCH1, a tumor suppressor protein, functions upstream of GLI1. Loss of PTCH1 induces GLI1 activation and downstream gene transcription. Utilizing fresh tissue from the index PF case, RT-qPCR analysis demonstrated expression of Hh pathway components, SMO and GLI1, as well as GLI1 transcriptional targets, CCND1 and HHIP. In turn, short-term in vitro treatment with a Hh pathway inhibitor, sonidegib, resulted in dose-dependent cell killing.

Conclusions

For the first time, we report a novel association between PTCH1 inactivation and the development of plexiform fibromyxoma. Hh pathway inhibition with SMO antagonists may represent a target to study for treating a subset of plexiform fibromyxomas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

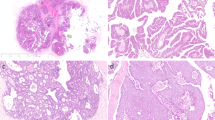

Plexiform fibromyxoma (PF) is a rare submucosal gastric tumor with unknown incidence that can be confused with myxoid gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) [1]. While slow growth and lack of metastases suggest an indolent natural history, these so-called “benign” tumors often present with upper gastrointestinal bleeding and gastric outlet obstruction. Although the cell of origin remains unknown, PF generally occurs in the gastric muscularis propria and frequently invades into the mucosa and submucosa [1,2,3,4]. Histologically, PF is characterized by a multinodular plexiform growth pattern, diffuse myxoid stroma and prominent thin arborizing capillaries. Immunohistochemically, PF is characterized by expression of α-SMA (alpha smooth muscle actin) while lacking expression for CD117 (KIT, c-KIT), DOG-1 (discovered on GIST-1), CD34, S-100, desmin (or focal), and cytokeratins. On this basis, PF can be differentiated from GIST, as well as leiomyoma, leiomyosarcoma, schwannoma, gastric carcinoids, and desmoids [1, 3].

To date, there has been only one report investigating the molecular biology of PF. The authors demonstrated that 5 of 16 tumors had activation of the GLI1 oncogene, a transcription factor in the hedgehog (Hh) pathway [5]. Two tumors were found to have GLI1 amplification, while three had MALAT1-GLI1 oncogenic fusions. Both types of GLI1 genomic alterations resulted in overexpression of GLI1 protein and activation of Hh signaling. This highly conserved pathway has been implicated in the biology of several types of cancers, including gastroblastoma [6], basal cell carcinoma [7], medulloblastoma [8], rhabdomyosarcoma [9], hepatocellular carcinoma [10], and GIST [11], as well as tumors with plexiform and fibromyxoid histologies [12]. The pathway is activated when the hedgehog ligands, namely sonic hedgehog (SHH), indian hedgehog (IHH) and desert hedgehog (DHH) ligands, bind to their receptor, Patched 1 (PTCH1), a multi-pass transmembrane protein. In an unbound state, PTCH1 negatively regulates smoothened (SMO), a seven-transmembrane domain proto-oncoprotein. Following ligand binding, the PTCH1 tumor suppressor protein releases SMO inhibition, which then leads to activation of the GLI family of transcription factors that includes the GLI1 proto-oncoprotein. In turn, GLI1 regulates expression of many genes involved in cell cycle progression, including Cyclin D1 (CCND1), as well as members of the Hh pathway itself, including PTCH1, GLI1, and hedgehog-interacting protein (HHIP) [13]. Thus, oncogenic mutation of SMO or GLI1, as well as inactivating mutations of PTCH1 can activate the pathway and downstream transcription [13]. However, only SMO and PTCH1-altered tumors can be targeted with the three FDA-approved SMO inhibitors, namely sonidegib (Novartis/Sun), vismodegib (Genetech-Roche), and glasdegib (Pfizer).

The PTCH1 tumor suppressor gene is located on the long arm of chromosome 9 (9q22.32). Over 500 different PTCH1 mutations have been implicated in Gorlin syndrome (i.e., basal cell carcinoma and rhabdomyosarcoma), sporadic basal cell carcinoma, holoprosencephaly, keratocystic odontogenic tumors, and ocular developmental anomalies [14]. Herein, we present the first report of recurrent PTCH1 loss in plexiform fibromyxoma based on next generation sequencing. This newly identified genetic alteration is the first tumor suppressor associated with PF tumorigenesis. In turn, we examined the role of PTCH1 inactivation on Hh signaling and investigated a rational approach to pharmacologically treating PTCH1-, but not GLI1-mutated PF, with SMO inhibitors.

Methods

Human subjects

Written informed consent was obtained for all study participants, including publication of clinical data. Patient tissue collection, acquisition of clinical data, and conducting experimental procedures on biological samples was approved or exempt by each institutional IRB [UC San Diego Human Research Protections Program Institutional Review Board (IRB) Protocol #090401, NCI Office of Human Subjects Research (OHSR) IRB exemption was granted for work with anonymized annotated human samples, and OHSU IRB exemption was granted for contribution of one patient to the study cohort]. All experiments were conducted in accordance with appropriate regulatory guidelines for use of human tissue. Excess explant tissue was collected for study. An index case from UCSD served as the initial observation for this study. Additional patients were retrospectively identified from the NCI and OHSU. These were analyzed in a validation cohort.

Pathologic diagnosis

Pathologic diagnosis was performed at each institution. In general, pathologic diagnosis of PF requires histopathology showing spindle shaped cells, diffuse or focally plexiform architecture, prominent thin capillaries and a bland myxoid background. Additionally, immunohistochemical staining is characteristically positive for α-SMA while negative for CD117, CD34, DOG-1, and S-100.

Primary tumor dissociation and single cell suspension

Excess fresh tumor tissue was dissociated into single cell suspensions using the gentleMACS Dissociator (Miltenyi Biotec, San Diego, CA) as previously described [15]. Solid tissues were cut into 5-mm size pieces and were transferred to a gentleMACS C-Tube containing RPMI 1640 media and MACS human tumor dissociation enzyme solution (Miltenyi Biotec) according to manufacturer’s instructions for tough tumor tissue (h_Tumor_01). The sample was then passed through a 70 μm filter, and tumor cells were collected following centrifugation. The single cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Mediatech, Manassas, VA) and 2 mM glutamine (Mediatech).

Next generation sequencing

Sequencing was performed on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) sections (6 tumors from National Cancer Institute (NCI), 1 tumor from Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU) and 1 tumor from University of California, San Diego (UCSD). FoundationOne-Heme Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) was performed on Tumor 1 as previously described [16]. Briefly, DNA was extracted from FFPE sections with a minimum of 20% tumor tissue. DNA was submitted for comprehensive genomic profiling with hybridization-captured, adaptor ligation-based libraries. The FoundationOne-Heme test interrogates a cancer-related library of 400 gene-associated genes, 30 introns and 250 RNA transcripts tailored for hematologic malignancy and sarcoma [17]. Tumors 2–5 were analyzed by the GeneTrails Comprehensive Solid Tumor Panel (Knight Diagnostic Laboratories, OHSU), which is a DNA sequencing panel that screens for alterations in 124 known oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes. DNA extracted from FFPE tumor tissue must provide a minimum of 50 ng DNA content, which is required to achieve a minimum depth of 250 reads per amplicon. Samples that had less than this minimum required DNA content did not undergo NGS analysis. In addition, Tumors 2–5 were subjected to RNA sequencing using the GeneTrails Solid Tumor Fusion Gene Panel (Knight Diagnostic Laboratories, OHSU), which is a partner-agnostic assay for gene fusions across 22 cancer-related target genes. RNA extracted from FFPE tumor tissue required a minimum of 30 ng RNA content for adequate analysis. Samples with less than the required amount were not analyzed by RNASeq.

RNA preparation and expression quantification

Total RNA for in vitro experiments was prepared from single cell suspension using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). RNA quality was assessed with the Nanodrop 2000 (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). Reverse transcription quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) was performed on a CFX96 real-time system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) using SsoFast EvaGreen Supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Each sample was tested in triplicate. Forward and reverse primer sequences are as previously described [10, 18]. The threshold cycle (Ct) of target genes were normalized to ACTB according to delta-Ct method [18]. PCR transcript expression and appropriate size were validated by gel electrophoresis using a 2.0% agarose gel in 1× Tris–acetate-EDTA buffer.

Cell viability assay

Single cell suspensions of tumor cells were seeded at 2500 cells per well on a 96-well plate (Corning, Lowell, MA). The cells were grown for 48 h and subsequently treated with Sonidegib (LDE225, Novartis, Basel, Switzerland) with a titration of 50-, 25-, 12.5- and 6.25-μM for 72 h based upon prior reports in mantle cell lymphoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, and chronic myeloid leukemia [19,20,21]. The CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Cell Viability Assay (Promega, Madison, WI) was performed and luminescence measured on the Tecan Infinite 200 microplate reader (Tecan, Männedorf, Switzerland).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Prism GraphPad 7 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Comparison were made using student’s t-test and statistical significance was accepted at the 5% level. Inhibitor concentration-50 (IC50) was calculated using GraphPad 7.

Results

Patient demography

Overall, eight cases of pathology confirmed plexiform fibromyxoma were examined from three institutions. An index case (Tumor 1) served as the initial observation and then seven additional patients were retrospectively identified and analyzed in a validation cohort (Table 1). Overall, the median age at diagnosis was 45.5 years old (range 16–65 years). There were five females (62.5%) and three males in the cohort. Tumor locations were distributed throughout the stomach, except one tumor that was described as originating from the duodenum. The median tumor size was 3.5 cm (range 2.8–11 cm).

Next generation sequencing (NGS)

DNA and RNA extraction were performed on FFPE samples for all tumors. DNA extraction met minimum quality requirements in 4 out of 8 samples (50%) and RNA extraction met minimum quality requirements in 5 out of 8 samples (62.5%). NGS was performed by either the FoundationOne-Heme Panel (Tumor 1, Foundation Medicine) or GeneTrails Comprehensive Solid Tumor and Fusion Gene Panels (Tumors 2–5, Knight Diagnostic Laboratories, OHSU). Overall, 3 out of 5 samples had alterations in cancer-related genes and no gene fusion products were detected (Table 1).

Index case

Tumor 1

NGS identified a partial PTCH1 deletion of exons 15–24 on chromosome 9q (Fig. 1). This mutation corresponds to a partial loss of the 4th extracellular loop (ECL) and complete loss of the 5th and 6th ECLs, as well as loss of transmembrane domains 8 thru 12, the 4th and 5th intracellular loops (ICLs), and the C-terminus cytoplasmic domain. This predicts a loss of tumor suppressor function due to altered inhibition of the SMO proto-oncoprotein. In addition, the tumor also had genomic alterations in NOTCH1 L2457V (designated as a benign genomic alteration in ClinVar) and NOD1 L475fs*35. Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing protein 1 (NOD1) involved in the recognition of bacterial molecules and stimulation of an immune reaction [22]. Thus, we suspect that these are passenger mutations.

(Adapted from https://www.genecards.org and https://www.atlasgeneticsoncology.org, respectively)

PTCH1 gene schematic. a PTCH1 origin on q arm of chromosome 9, b full length transcript with 24 exons and c mutant PTCH1 with deletion of exons 15–24

Validation cohort

Tumor 2

Tumor 2 had bi-allelic chromosome 9q deletions of PTCH1 and FANCC (Fanconi anemia complementation group C). FANCC encodes a protein involved in homologous recombination repair of damaged DNA and delaying apoptosis. Whether loss of FANCC played a role in the development of this tumor is unclear. Examination of the involved chromosomal loci (Chr9: 95,099,054–95,517,057 from GRCh38/hg38 in UCSC Genome Browser [23]) shows that FANCC and PTCH1 are the only coding genes located within this position. Loss of both FANCC and PTCH1 suggests a long-range deletion of chromosome 9 that likely encompassed at least partial deletions of both genes. However, it is certainly possible that the deletion encompassed a larger region that was not detected by the GeneTrails panel.

Tumor 3

A third tumor was found to have bi-allelic chromosome 12 deletions of CDKN1B, DDX11 and ERBB3. CDKN1B encodes p27Kip1, which regulates cell cycle progression by inhibiting cyclin E-CDK2 and cyclin D-CDK4. The DDX11 gene encodes a DNA/RNA helicase that has myriad functions in maintenance of genomic stability, chromosomal organization in mitosis and translation initiation. ERBB3 encodes HER3 (human epidermal growth factor receptor 3), which has not been found to be independently oncogenic but forms active heterodimers with ErbB2. The loci of genes affected [CDKN1B (12p13.1), DDX11 (12p11.21), and ERBB3 (12q13.2)] are distributed throughout chromosome 12 suggesting that individual alterations, not long-range deletions, occurred. Furthermore, proximate and intervening genes such as CCND2 (12p13.32), KRAS (12p12.1) and MDM2 (12q15) were found to be intact, also suggesting that the chromosome 12 deletions were partial (or full) gene deletions of individual loci rather than long-range deletions. Tumor 3 also had bi-allelic loss of CHEK1 on chromosome 11. Checkpoint kinase 1 (Chk1), the protein product of CHEK1, is involved in surveillance of genomic integrity and is necessary for initiation of the DNA damage checkpoint. We suspect that CHEK1 (11q24.2) was altered by a partial or full-length deletion rather than a long-range deletion because an neighboring gene, SDHD (11q23), was intact. However, a long-range deletion that encompassed other genes than CHEK1, but were not assessed by the GeneTrails panel, cannot be excluded.

Tumors 4–5

Two tumors did not have any cancer-associated genetic alterations detected on NGS by the GeneTrails panel (124 known oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes), although this does not rule out that other genes may be involved in tumorigenesis.

Tumors 6–8

Three tumors did not meet minimum requirements for DNA quality for analysis by NGS.

Hh pathway is expressed in PTCH1-inactivated PF

Tumors 1 and 2 both had genetic alterations causing loss of the PTCH1 gene. To assess whether PTCH1 deletion was associated with activation of Hh signaling, we performed quantitative RT-PCR analysis of Hh pathway components and Hh target genes. Fresh tumor tissue was available from Tumor 1 (index case) and was utilized for in vitro assays. This analysis demonstrated mRNA expression of Hh pathway components (PTCH1, SMO, GLI1, GLI2 and GLI3) as well as downstream GLI1 transcriptional targets (CCND1 and HHIP) (Fig. 2). It is noteworthy that PTCH1 and GLI1 are both Hh pathway components and are also GLI1 transcriptional targets. In the tumor, the Hh pathway ligands, SHH and IHH, had undetectable expression consistent with ligand-independent Hh pathway activation following PTCH1 inactivation (Additional file 1: Figure S1).

Hedgehog pathway is expressed in PTCH1-inactivated plexiform fibromyxoma. a Validation of transcript PCR products on agarose gel electrophoresis (cropped as shown; full length gel is presented in Additional file 1: Figure S1) and b relative quantification of expressed hedgehog pathway components using the delta-Ct method. Experiments performed in triplicate (N = 3)

PTCH1-inactivated PF is sensitive to targeted Hh inhibition

We next performed cell killing assays with a SMO proto-oncoprotein inhibitor to assess the cellular dependency on Hh signaling. Viable tissue from Tumor 1 was dissociated into single cell suspension and plated in cell culture. Treatment of the primary tumor cells with the Hh pathway inhibitor, sonidegib (LDE225, Novartis), resulted in dose-dependent cell killing with an IC50 of 27 μM (Fig. 3 and Additional file 1: Figure S2). Drug dose range was selected for IC50 finding based on literature cited values [19,20,21]. Thus, targeting PTCH1-mutant PF cells with a SMO inhibitor resulted in tumor cell death.

Dose-dependent cell death in PTCH1-inactivated PF following SMO inhibitor treatment. Four-point dose titration of sonidegib treatment. Absolute experimental and control data shown in Additional file 1: Figure S2. Experiments performed in triplicate (N = 3). *P < 0.001

Discussion

In a recent study, GLI1 upregulation through a MALAT1-GLI1 fusion or copy number amplification was detected in a subset of PF [5]. Spans et al. demonstrated the critical nature of Hh signaling in this disease. Here, we identified two cases of plexiform fibromyxoma (PF) with genomic loss of PTCH1, a tumor suppressor gene in the hedgehog pathway. Quantitative PCR of one of these tumors supported ligand-independent activation of the Hh pathway. In addition, targeting smoothened in the context of PTCH1 inactivation resulted in cell killing of primary PF cells. This approach represents the first in vitro use of a targeted therapeutic strategy for this rare tumor.

Our new findings lend further support for a primary role of aberrant Hh signaling in PF pathophysiology. In contrast to the previously reported GLI1 alteration, we observed loss of PTCH1, indicating that events occurring upstream in the Hh pathway can also drive PF growth [5]. Although it is possible that non-canonical activation of the Hh pathway accounts for the expression of Hh pathway components, we believe this is unlikely since non-canonical Hh activation usually results in low SMO levels whereas Smo mRNA was found to be high in Tumor 1 [24, 25]. We also show that targeted SMO inhibition in vitro, which lies downstream of PTCH1, but upstream of GLI1, leads to dose-dependent cell killing of PF cells. This supports the role of PTCH1/SMO-axis oncogenesis since non-canonical Hh activation is SMO-independent and usually resistant to SMO inhibition. In contrast to PTCH1-mutated PF, GLI1 upregulated PFs are predicted to be resistant to SMO inhibition. Thus, our new findings provide evidence for a possible therapeutic role of Hh inhibition in the treatment of PTCH1-inactivated PF. Additional testing using in vivo models will be necessary to determine whether SMO inhibition is a viable strategy for treating patients with PTCH1-inactivated PF.

Hedgehog signaling has been associated with several tumor types. In fact, germline PTCH1 mutations underlie nevoid basal-cell carcinoma syndrome, also known as Gorlin Syndrome. This is an autosomal dominant condition associated with distinctive facial abnormalities, as well as, basal cell carcinomas and mesenchymal tumors. Interestingly, histopathologic features of tumors associated with Gorlin Syndrome bear striking similarities to plexiform fibromyxoma. For example, Gorlin-associated odontogenic myxofibrous tumors have a bland myxoid appearance in a plexiform pattern [26]. Similarly, a subset of pediatric gastric pericytomas have been associated with an ACTB-GLI1 gene fusion [27]. Additionally, six cases of malignant epithelioid neoplasms with frequent S100-positivity were all found to have GLI1 fusions involving ACTB, MALAT1 or PTCH1 [28]. These tumors may represent a histologically novel class of pericytoma or soft tissue sarcoma distinct from plexiform fibromyxoma. Collectively, these observations underscore a strong genotypic-to-histopathologic/morphologic relationship in PTCH1 associated diseases.

In addition to syndromic diseases, PTCH1 mutations have been implicated in several cancers including sporadic basal cell carcinoma (BCC) [29], squamous cell carcinoma [30], medulloblastoma [8], and embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma [31]. There are over 500 PTCH1 mutations described in human disease [14]. The mono-allelic exon 15–24 deletion of PTCH1 in Tumor 1 would be predicted to truncate the C-terminal region. Interestingly, elegant mutagenesis experiments in Drosophila have shown that the C-terminus of ptch1 is necessary for inhibition of the Hh pathway and that deletion of the last 156 residues produces a ligand-independent dominant negative phenotype [32, 33]. Consistent with these data, PTCH1 haploinsufficiency has been reported in variety of cancer types, including basal cell carcinoma, medulloblastoma, and rhabdomyosarcoma [34]. Furthermore, “one-hit” PTCH1 inactivation has been described in up to one-third of patients with nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome (NBCCS) who have mono-allelic PTCH1 mutations [35]. Taken together, this suggests that single allele inactivation of PTCH1 can have a dominant negative effect and may account for Hh activation, as well as tumorigenesis, in a subset of PF.

Based on the prior observation of GLI1 overexpression in PF and the present identification of PTCH1 inactivation, it appears that there are two distinct subsets of PF identified to date. It is interesting to note that the previously reported MALAT1-GLI1 fusion protein implicates chromosomal loci 11q13 (MALAT1) and 12q13 (GLI1). Tumor 3 from our cohort showed loss of ERBB3 (12q13; close to GLI1) and CHEK1 (11q24). Unfortunately, the RNA from this case was too degraded to screen for a possible GLI1 fusion.

There are several limitations to our study. First, primary cells were expanded in culture for several days before performing cell killing assays. Therefore, it is possible that these cells do not fully recapitulate in vivo biology. Second, the PF cells were not immortalized and we were limited in the amount of in vitro studies that could be performed before viable cells were exhausted. Thus, additional mechanistic studies including genetic PTCH1 rescue experiments, SMO knockdown experiments, and assessment of Hh target gene expression following SMO inhibitor treatment were not feasible. Development of an immortalized PF cell line would prove an extremely useful tool in further characterization of PF pathophysiology.

Conclusions

We report a novel association between PTCH1 inactivation and the development of plexiform fibromyxoma. Our findings demonstrate that tumor suppressor gene alterations (i.e., PTCH1), rather than oncogenic mutations (i.e., GLI1), within the Hh pathway are also associated with plexiform fibromyxoma. In turn, targeted Hh pathway inhibition with SMO antagonists may represent a target to study for treating a subset of plexiform fibromyxomas. Further studies are warranted to investigate the clinical efficacy of these agents in appropriately selected patients, as well as to determine the underlying biology of tumors lacking PTCH1 and GLI1 alterations.

Availability of data and materials

All permissible protected heath information is included in Table 1 on the clinical data of the cohort. In vitro data is available on request. No additional datasets or materials were generated or utilized in this study.

Abbreviations

- PF:

-

plexiform fibromyxoma

- PTCH1:

-

Patched 1

- SMO:

-

smoothened

- Hh:

-

hedgehog

- α-SMA:

-

alpha smooth muscle actin

- DOG-1:

-

discovered on GIST-1

- SHH:

-

sonic hedgehog

- IHH:

-

indian hedgehog

- DHH:

-

desert hedgehog

- CCND1:

-

cyclin D1

- HHIP:

-

hedgehog-interacting protein

- NGS:

-

next generation sequencing

- RT-qPCR:

-

reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- IC50:

-

inhibitory concentration 50%

- GIST:

-

gastrointestinal stromal tumor

- IRB:

-

Institutional Review Board

- FFPE:

-

formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded

- ECL:

-

extracellular loop

- ICL:

-

intracellular loop

- BCC:

-

basal cell carcinoma

- NBCCS:

-

nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome

References

Miettinen M, Makhlouf HR, Sobin LH, Lasota J. Plexiform fibromyxoma: a distinctive benign gastric antral neoplasm not to be confused with a myxoid gist. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33(11):1624–32.

Kane JR, Lewis N, Lin R, Villa C, Larson A, Wayne JD, Yeldandi AV, Laskin WB. Plexiform fibromyxoma with cotyledon-like serosal growth: a case report of a rare gastric tumor and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2016;11(3):2189–94.

Quero G, Musarra T, Carrato A, Fici M, Martini M, Dei Tos AP, Alfieri S, Ricci R. Unusual focal keratin expression in plexiform angiomyxoid myofibroblastic tumor: a case report and review of the literature. Medicine. 2016;95(28):e4207–e4207.

Kawara F, Tanaka S, Yamasaki T, Morita Y, Ohara Y, Okabe Y, Hoshi N, Toyonaga T, Umegaki E, Yokozaki H, et al. Gastric plexiform fibromyxoma resected by endoscopic submucosal dissection after observation of chronological changes: a case report. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2017;9(6):263–7.

Spans L, Fletcher CDM, Antonescu CR, Rouquette A, Coindre J-M, Sciot R, Debiec-Rychter M. Recurrent MALAT1-GLI1 oncogenic fusion and GLI1 up-regulation define a subset of plexiform fibromyxoma. J Pathol. 2016;239(3):335–43.

Graham RP, Nair AA, Davila JI, Jin L, Jen J, Sukov WR, Wu TT, Appelman HD, Torres-Mora J, Perry KD, et al. Gastroblastoma harbors a recurrent somatic MALAT1-GLI1 fusion gene. Mod Pathol. 2017;30(10):1443–52.

Gailani MR, Bale SJ, Leffell DJ, DiGiovanna JJ, Peck GL, Poliak S, Drum MA, Pastakia B, McBride OW, Kase R. Developmental defects in Gorlin syndrome related to a putative tumor suppressor gene on chromosome 9. Cell. 1992;69(1):111–7.

Archer TC, Weeraratne SD, Pomeroy SL. Hedgehog-GLI pathway in medulloblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(17):2154–6.

Pressey JG, Anderson JR, Crossman DK, Lynch JC, Barr FG. Hedgehog pathway activity in pediatric embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma and undifferentiated sarcoma: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;57(6):930–8.

Sicklick JK, Li YX, Jayaraman A, Kannangai R, Qi Y, Vivekanandan P, Ludlow JW, Owzar K, Chen W, Torbenson MS, et al. Dysregulation of the hedgehog pathway in human hepatocarcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27(4):748–57.

Tang CM, Lee TE, Syed SA, Burgoyne AM, Leonard SY, Gao F, Chan JC, Shi E, Chmielecki J, Morosini D, Wang K, Ross JS, Kendrick ML, Bardsley MR, Siena M, Mao J, Harismendy O, Ordog T, Sicklick JK. Hedgehog pathway dysregulation contributes to the pathogenesis of human gastrointestinal stromal tumors via GLI-mediated activation of KIT expression. Oncotarget. 2016;7(48):78226–41.

Wu J, Williams JP, Rizvi TA, Kordich JJ, Witte D, Meijer D, Stemmer-Rachamimov AO, Cancelas JA, Ratner N. Plexiform and dermal neurofibromas and pigmentation are caused by Nf1 loss in desert hedgehog-expressing cells. Cancer Cell. 2008;13(2):105–16.

Adolphe C, Hetherington R, Ellis T, Wainwright B. Patched1 functions as a gatekeeper by promoting cell cycle progression. Cancer Res. 2006;66(4):2081–8.

Fokkema IF, Taschner PE, Schaafsma GC, Celli J, Laros JF, den Dunnen JT. LOVD v.2.0: the next generation in gene variant databases. Hum Mutat. 2011;32(5):557–63.

Fox RG, Lytle NK, Jaquish DV, Park FD, Ito T, Bajaj J, Koechlein CS, Zimdahl B, Yano M, Kopp J, et al. Image-based detection and targeting of therapy resistance in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2016;534(7607):407–11.

Burgoyne AM, Siena MD, Alkhuziem M, Tang C-M, Medina B, Fanta PT, Belinsky MG, Von Mehren M, Thorson JA, Madlensky L, et al. Duodenal-jejunal flexure GI stromal tumor frequently heralds somatic NF1 and notch pathway mutations. JCO Precis Oncol. 2017;1:1–12.

Frampton GM, Fichtenholtz A, Otto GA, Wang K, Downing SR, He J, Schnall-Levin M, White J, Sanford EM, An P, et al. Development and validation of a clinical cancer genomic profiling test based on massively parallel DNA sequencing. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31(11):1023–31.

Tang CM, Lee TE, Syed SA, Burgoyne AM, Leonard SY, Gao F, Chan JC, Shi E, Chmielecki J, Morosini D, et al. Hedgehog pathway dysregulation contributes to the pathogenesis of human gastrointestinal stromal tumors via GLI-mediated activation of KIT expression. Oncotarget. 2016;7(48):78226–41.

Zhang H, Chen Z, Neelapu SS, Romaguera J, McCarty N. Hedgehog inhibitors selectively target cell migration and adhesion of mantle cell lymphoma in bone marrow microenvironment. Oncotarget. 2016;7(12):14350–65.

Irvine DA, Zhang B, Kinstrie R, Tarafdar A, Morrison H, Campbell VL, Moka HA, Ho Y, Nixon C, Manley PW, et al. Deregulated hedgehog pathway signaling is inhibited by the smoothened antagonist LDE225 (Sonidegib) in chronic phase chronic myeloid leukaemia. Sci Rep. 2016;6:25476.

Ridzewski R, Rettberg D, Dittmann K, Cuvelier N, Fulda S, Hahn H. Hedgehog inhibitors in rhabdomyosarcoma: a comparison of four compounds and responsiveness of four cell lines. Front Oncol. 2015;5:130.

Caruso R, Warner N, Inohara N, Núñez G. NOD1 and NOD2: signaling, host defense, and inflammatory disease. Immunity. 2014;41(6):898–908.

Kent WJ, Sugnet CW, Furey TS, Roskin KM, Pringle TH, Zahler AM, Haussler D. The human genome browser at UCSC. Genome Res. 2002;12(6):996–1006.

Zhou J, Zhu G, Huang J, Li L, Du Y, Gao Y, Wu D, Wang X, Hsieh JT, He D, et al. Non-canonical GLI1/2 activation by PI3K/AKT signaling in renal cell carcinoma: a novel potential therapeutic target. Cancer Lett. 2016;370(2):313–23.

Po A, Silvano M, Miele E, Capalbo C, Eramo A, Salvati V, Todaro M, Besharat ZM, Catanzaro G, Cucchi D, et al. Noncanonical GLI1 signaling promotes stemness features and in vivo growth in lung adenocarcinoma. Oncogene. 2017;36(32):4641–52.

Regezi JA. Odontogenic cysts, odontogenic tumors, fibroosseous, and giant cell lesions of the jaws. Mod Pathol. 2002;15(3):331–41.

Castro E, Cortes-Santiago N, Ferguson LM, Rao PH, Venkatramani R, Lopez-Terrada D. Translocation t(7;12) as the sole chromosomal abnormality resulting in ACTB-GLI1 fusion in pediatric gastric pericytoma. Hum Pathol. 2016;53:137–41.

Antonescu CR, Agaram NP, Sung YS, Zhang L, Swanson D, Dickson BC. A distinct malignant epithelioid neoplasm with GLI1 gene rearrangements, frequent S100 protein expression, and metastatic potential: expanding the spectrum of pathologic entities with ACTB/MALAT1/PTCH1-GLI1 fusions. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42(4):553–60.

Gailani MR, Ståhle-Bäckdahl M, Leffell DJ, Glynn M, Zaphiropoulos PG, Pressman C, Undén AB, Dean M, Brash DE, Bale AE, et al. The role of the human homologue of Drosophila patched in sporadic basal cell carcinomas. Nat Genet. 1996;14(1):78–81.

Al-Rohil RN, Tarasen AJ, Carlson JA, Wang K, Johnson A, Yelensky R, Lipson D, Elvin JA, Vergilio JA, Ali SM, et al. Evaluation of 122 advanced-stage cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas by comprehensive genomic profiling opens the door for new routes to targeted therapies. Cancer. 2016;122(2):249–57.

Taeubner J, Brozou T, Qin N, Bartl J, Ginzel S, Schaper J, Felsberg J, Fulda S, Vokuhl C, Borkhardt A, et al. Congenital embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma caused by heterozygous concomitant PTCH1 and PTCH2 germline mutations. Eur J Hum Genet. 2018;26(1):137–42.

Hime GR, Lada H, Fietz MJ, Gillies S, Passmore A, Wicking C, Wainwright BJ. Functional analysis in Drosophila indicates that the NBCCS/PTCH1 mutation G509V results in activation of smoothened through a dominant-negative mechanism. Dev Dyn. 2004;229(4):780–90.

Johnson RL, Milenkovic L, Scott MP. In vivo functions of the patched protein: requirement of the C terminus for target gene inactivation but not hedgehog sequestration. Mol Cell. 2000;6(2):467–78.

Calzada-Wack J, Kappler R, Schnitzbauer U, Richter T, Nathrath M, Rosemann M, Wagner SN, Hein R, Hahn H. Unbalanced overexpression of the mutant allele in murine Patched mutants. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23(5):727–33.

Pan S, Dong Q, Sun LS, Li TJ. Mechanisms of inactivation of PTCH1 gene in nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome: modification of the two-hit hypothesis. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(2):442–50.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Peter Zage and Jacqueline Lesperance for their technical assistance. We thank the Biorepository and Tissue Technology Shared Resource (NIH P30 CA023100) at the University of California, San Diego for their assistance and support.

Funding

We appreciate funding support from the Surgical Society of the Alimentary Tract (SSAT) Mentored Research Award (S.B.) for salary support and laboratory supplies as well as NIH T32 CA121938 Cancer Therapeutics (CT2) Training Fellowship (S.B.) for salary support. In addition, we appreciate funding support for laboratory supplies provided by Hope for a Cure Foundation (J.K.S.), The Life Raft Group (J.K.S.), Kristen Ann Carr Fund (J.K.S.), Lighting the Path Forward for GIST Cancer Research (J.K.S.), NIH K08 CA168999 (J.K.S.), NIH R21 CA192072 (J.K.S.), and NIH R01 CA226803 (J.K.S.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SB, SN, AMB, and JKS wrote the main manuscript text. SB, MMM, CC, SN, RU, MY, CMT, and JLD assisted with preparation of the figures. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained for all study participants, including publication of clinical data. Patient tissue collection, acquisition of clinical data, and conducting experimental procedures on biological samples was approved or exempt by each institutional IRB [UC San Diego Human Research Protections Program Institutional Review Board (IRB) Protocol #090401, NCI Office of Human Subjects Research (OHSR) IRB exemption was granted for work with anonymized annotated human samples, and OHSU IRB exemption was granted for contribution of one patient to the study cohort]. All experiments were conducted in accordance with appropriate regulatory guidelines for use of human tissue. Excess explant tissue was collected for study.

Consent for publication

Written consent for publication of clinical data was obtained for all study participants at each institution.

Competing interests

JK.S. has research funding from Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Amgen Pharmaceuticals and Foundation Medicine. J.K.S. also serves or served as Consultant to the following organizations: Grand Rounds (2015–2018), and Loxo Oncology (2017–2018). These disclosures had no impact on any of the work presented in this manuscript. There are no competing interests to declare by the remaining authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1: Figure S1.

Validation of transcript PCR products on agarose gel electrophoresis (full length gel).

Additional file 2: Figure S2.

Absolute experimental and control data for cell viability assay.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Banerjee, S., Corless, C.L., Miettinen, M.M. et al. Loss of the PTCH1 tumor suppressor defines a new subset of plexiform fibromyxoma. J Transl Med 17, 246 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-019-1995-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-019-1995-z