Abstract

Background

Patients with HBsAg-positive gastric cancer (GC) are a heterogeneous group, and it is not possible to accurately predict the overall survival (OS) in these patients.

Methods

We developed and validated a nomogram to help improve prediction of OS in patients with HBsAg-positive GC. The nomogram was established by a development cohort (n = 245), and the validation cohort included 84 patients. Factors in the nomogram were identified by univariate and multivariate Cox hazard analysis. We tested the accuracy of the nomograms by discrimination and calibration, and plotted decision curves to assess the benefits of nomogram-assisted decisions in a clinical context. Then we evaluated the risk in the two cohort.

Results

Significant predictors were age, tumor stage, distant metastases, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) and alkaline phosphatase (ALP). The proportional-hazards model (nomogram) was based on pre-treatment characteristics. The nomogram had a concordance index (C-index) of 0.812 (95% CI 0.762–0.862), which was superior than the C-index of AJCC TNM Stage (0.755, 95% CI 0.702–0.808). The calibration plot in the validation cohort based on 5 predictors suggested good agreement between actual and nomogram-predicted OS probabilities. The decision curve showed that the nomogram in predicting OS is better than that of TNM staging system in all range. Moreover, patients were divided into three distinct risk groups for OS by the nomogram: low risk group, middle risk group and high risk group, respectively.

Conclusion

This nomogram, using five pre-treatment characteristics, improves prediction of OS in patients with HBsAg-positive gastric cancer. It represents an improvement in prognostication over the current TNM stage. To generalize the use of this nomogram in other groups, additional validation with data from other institutions is required.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Gastric cancer (GC) is one of the most common malignancies and ranks the second leading cause of cancer death worldwide, with about one million new cases reported every year [1]. It was also commonly diagnosed and were recognized as leading causes of cancer death in China [1]. Chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection has been well recognized as one of the major causes of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [2]. However, in recent years, HBV infection has been reported to be associated with Gastric cancer (GC) [3], endometrial carcinoma [4] and nasopharyngeal carcinoma [5], though the underlying mechanism needs further investigation. Furthermore, HBV infection was associated with earlier cancer diagnosis and prognosis [6]. The biochemical parameters of liver function tests (LFT) are responsible for the metabolism and excretion of various endogenous and exogenous substances [7]. And for gastric cancer with HBsAg-positive, accurate assessment of liver function is key to the selection of treatment options.

The most commonly and widely used staging system for gastric cancer is the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC)/American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) tumor, lymph node and metastases (TNM) staging system [8, 9]. The TNM staging system divides gastric cancer patients into different stages according to the depth of primary tumor invasion (T stage), regional lymph node metastasis (N stage) and distant metastasis (M stage) [10, 11]. Large variations are reported in the clinical outcomes, even patients with the same stage and similar treatment strategies [9, 12, 13]. This findings indicate that the present staging system is inadequate for predicting recurrence and does not reflect the biological heterogeneity of HBsAg-positive GC patients [12]. However, many other risk factors, such as age, sex and LFT should be considered for predicting individualized prognosis.

In this study, we aimed to develop and validate a prognostic nomogram that uses widely available pretreatment clinical and laboratory data to improve our ability to predict HBsAg-positive GC. We also performed a test to determine whether this model provides a more accurate prediction of prognosis when compared with TNM staging system.

Methods

Patient selection

The retrospectively study included 319 patients with histologically diagnosed GC with hepatitis B viral infection from 2009 to 2017 in Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center (SYSUCC, Guangdong, China). All the patients were classified as the first record of hospitalizations and the clinical information were extracted from Electronic Medical Record (EMR) system. The levels of LFT factors were investigated before treatment Laboratory Information System (LIS). The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients with a confirmed histologically diagnosed of GC; (2) patients with HBsAg-positive, but without other types of hepatitis viruses (i.e. hepatitis A viral, hepatitis C viral); (3) patients without second tumor, or indefinite diagnoses; (4) patients with complete clinical data; (5) patients without diseases influenced LFT (i.e. acute hepatitis, liver cirrhosis); (6) patients without any treatment. We divided patients into two cohorts by the time sequence. The primary cohort comprised 235 patients from August 2008 to September 2015. The validation cohort was contained 84 GC patients from September 2015 to January 2017 with age and sex match to the primary cohort. All patients provided written informed consent. The Institute Research Ethics Committee of the Sun Yat-Sen University Cancer Center, Guangzhou, China approved this study. The authenticity of this article has been validated by uploading the key raw data onto the Research Data Deposit public platform (http://www.researchdata.org.cn), with the approval RDD number as RDDA2019001020.

Laboratory measurements

All the patients received routine tests at the first visit in our hospital. Blood samples were collected at room temperature, then centrifuged at 3500 r/min for 10 min, which could be used to estimate the level of LFT biomarkers, including alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT), total bile acid (TBA), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), albumin (ALB), total bilirubin (TBIL), apolipoprotein A1 (ApoA1), apolipoprotein B (ApoB), prothrombin time (PT), fibrinogen (Fbg). HBV infection markers including HbsAg, hepatitis B surface antibody (HbsAb), hepatitis B e antigen (HbeAg) hepatitis B e antibody (HbeAb) and hepatitis B core antibody (HbcAb) were recorded.

Follow-up

All GC patients were advised to receive regular follow-ups after completion of the primary therapy according to clinical guidelines. Patients were generally followed up every 3 months in the first 2 years and annually thereafter for patients without evidence of recurrence in the following 3 to 5 years. Patients who did not visit our hospital as scheduled were telephoned for follow-ups to obtain the treatment information and living status (performed by The Medical Information Unit in our Cancer Center). The last follow-up occurred in September 2018. The outcome of our study was overall survival (OS). OS was defined as the time from the diagnosis of HCC to the date of the last follow-up or death.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 16.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA) and R for Windows (version 3.4.2, http://www.r-project.org/). The optimal cut-off points in our study were evaluated by minimum P value from log-rank × 2 statistics using the X-tile program [14] and continuous variables were transformed to categorical variables, while the categorical variables were classified based on clinical findings. Univariate and multivariate regression analysis was used to analyze the risk factors in the primary cohort, A nomogram was formulated based on the results of multivariate analysis by the package of rms. We tested the accuracy of the nomograms by discrimination and calibration both in primary and externa validation cohort. The discrimination of the nomogram was measured by Harrell’s C-index (C-index). The value of the C-index ranges from 0.5 to 1.0, with 0.5 indicating random chance and 1.0 indicating a perfect ability to correctly discriminate the outcome with the model. Then, the calibration curve of the nomogram model for the OS and decision curve analyses were performed. The total points of each patient were calculated according to the established Cox regression model, 3 groups of patients with different risk of prognosis (based on the total points) were delineated using the X-tile program. Survival curves were depicted by the Kaplan–Meier method, and using the dichotomized risk group as a factor, finally, compared using the log-rank test. All statistical tests were two-sided, and P values of less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Basic characteristics

The clinicopathologic characteristics of the training and validation sets were evaluated. The characteristics of the 235 consecutive AFP-negative HCC patients in the primary cohort and 84 patients in the validation cohort are showed in Table 1. There were 68 (28.94%) patients died, while 22 (26.19%) patients died respectively.

Biomarker selection

All the available informations, including clinicopathologic characteristics and biomarkers, were included for univariate and multivariate analysis (Table 2). In univariate analyse, Age, TNM stage, tumor stage, node stage, distant metastases, LDH, GGT, TBA, ALP, ALB, ApoB, Fbg were related to OS. All of the potentially important biomarkers identified in univariate analysis were further included in the multivariate analysis. Based on 235 HBsAg-positive GC patients with complete information, age, tumor stage, distant metastases, GGT and ALP were significant predictors of OS.

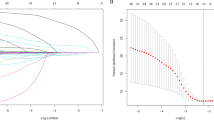

Development and validation of the prediction model

A nomogram is a graphic representation of the solution of an equation that provides a reasonable approximation of the probability of a particular outcome. The model explanatory covariables consisted of age, tumor stage, distant metastases, GGT and ALP. A nomogram was constructed to predict 1-, 3- and 5-year OS (Fig. 1). The validation of nomogram was consisted of discrimination and calibration Discrimination was performed by using a concordance index (C-index) Calibration was evaluated by comparing the means of predicted survival with estimating of predicted with observed Kaplan–Meier survival, with the x-axes are actual survival estimated by the nomogram, the y-axes are observed survival calculated by the Kaplan–Meier method. In the primary cohort, the C-index for OS prediction was 0.812 (95% CI 0.762–0.862). The calibration plot for the probability of OS at 1, 3 or 5 year after therapy showed an optimal agreement between the prediction by nomogram and actual observation (Fig. 2).

Nomogram, including age, tumor stage, distant metastases, GGT and ALP, for 1, 3 and 5 years overall survival (OS) in patients with HBsAg-positive GC. The nomogram is valued to obtain the probability of 1, 3 and 5 years survival by adding up the points identified on the points scale for each variable

Calibration curve of the nomogram in the primary and validation cohort, with the x-axes are actual survival estimated by the nomogram, the y-axes are observed survival calculated by the Kaplan–Meier method. a Three-year OS in the primary cohort. b Five-year survival OS in the primary cohort. c Three-year OS in the validation cohort

Validation of the predictive accuracy of nomograms for OS

We then applied the nomogram to the validation cohort of 84 HBsAg-positive GC patients.

The C-index for OS prediction was up to 0.821 (95% CI 0.723–0.919). The calibration plot for the probability of OS at 3-year after therapy showed an optimal agreement between the prediction by nomogram and actual observation (Fig. 2).

Furthermore, the discrimination of the nomogram and that of the AJCC TNM Stage have been compared. In the development cohort, the C-index of nomogram was 0.812 (95% CI 0.762–0.862), which was superior than the C-index of AJCC TNM Stage 0.755 (95% CI 0.702–0.808).

Decision curve analysis

The decision curve analysis for the nomogram and TNM staging systems is showed in Fig. 3. The decision curve presented that if the threshold probability of a patient is > 10%, the developed nomogram and TNM staging system in predicting OS is more benefit than all patients dead scheme or none patients dead scheme. Furthermore, the net benefit was comparable, the nomogram in predicting OS is more benefit than that of TNM staging system in this range.

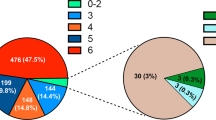

Comparison of predictive accuracy for OS between nomogram and TNM stage systems

Based on the nomogram, patients were divided into three groups: low-risk group, middle-risk group and a high-risk group, which showed good prognostic classification for HBsAg-positive GC both in development cohort and validation cohort. In the development cohort, there were 114 patients in the low-risk group, 49 patients in the middle-risk group, while 71 patients in the high-risk group. The OS between the three risk groups were (37.07 ± 16.80) months, (24.68 ± 18.31) months, (8.38 ± 6.33) months (P < 0.001). Also, in the validation cohort, there were 22 patients in the low-risk group, 49 patients in the middle-risk group, while 13 patients in the high-risk group. The mean OS between the three risk groups were (19.82 ± 10.07) months, (14.08 ± 9.76) months and (13.92 ± 7.15) months (P < 0.001) (Fig. 4).

Discussion

Gastric cancer (GC) is one of the most common malignant diseases in the digestive system, contributing to about 10% of annual deaths from cancer [15, 16]. The accurate tumor prognosis after definitive treatment is indispensable. The prevalence of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection varies largely worldwide. China is one of the relatively high prevalence area [17]. HBsAg recognized as an independent risk factor for both liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma [18]. It was also found that patients with liver cirrhosis had a high prevalence of gastric ulcers [19] and an increased risk of GC [20]. But, several studies have probed the existence of HBV in GC [3, 6] and HBV infection was associated with GC [3]. As HBV infection also exists in gastric mucosa epithelial cells, it may be possible that HBV infection increases the risk of GC in a similar mechanism of HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Therefore, for HBsAg-positive GC, it is important to consider the influence of HBV.

Traditional TNM staging system be used to assess the prognosis of HBsAg-positive GC [10, 21], which exists some drawbacks. The system only considers the anatomical extent of the disease without considering the liver biofunctional heterogeneity of HBsAg-positive GC, which does not fully reflect the accurate prognosis. It could not provides an more accurate estimate of prognosis particularly in patients with incurable cancers. Hence, we developed a prognostic nomogram to predict OS and treatment strategies guidance in HBsAg-positive GC with by using widely available baseline clinical and laboratory information. In our study, we found that tumor stage, age, distant metastases, GGT and ALP were the factors that influenced prognosis of patients according to the multivariate analysis. Patients with an earlier stage of T staging, M staging, and TNM stage, and a lower GGT and ALP level have improved survival rates. Not only should we consider the impact of HBV on liver function, but comprehensive liver function and TNM staging system, thus more accurate prediction of the patient’s prognosis.

Our nomogram is available to combine all these putative prognostic predictors into a summary measure for prediction of HBsAg-positive GC. It has demonstrated that the nomogram is better able to discriminate than the TNM staging system when used in GC patients with HBsAg-positive: In our model, the C-index for OS prediction was 0.812 (95% CI 0.762–0.862), for TNM staging system the C-index for OS prediction was 0.755 (95% CI 0.702–0.808). The nomogram showed better predictive accuracy for OS in development cohort. Simultaneously, validation of the nomogram also shows good predictive OS function. Furthermore, both in development cohorts and validation cohort, patients were divided into three group based on the nomogram, which could effectively discriminate the survival outcomes.

This nomogram is also a useful tool that utilizes conveniently available clinical information to provide simple prognostic information for oncologists and patients from complex statistical analysis. However, a major problem is to provide an accurate estimate of prognosis, especially, in patients with incurable cancers [22]. Traditional TNM staging system, which be used to assess the prognosis of GC, only considers the anatomical extent of the disease without considering the tumor heterogeneity. Previous articles have reported that the Italian Research Group for Gastric Cancer (GIRCG) prognostic scoring system (PSS) predicts the likelihood of recurrence after radical surgical treatment for GC, which is more accurate than TNM system to predict recurrence for high-risk patients [23]. Compared with the traditional TNM staging system, our method is more accurate and has a higher coincidence rate for patients with HBsAg-positive GC. Our method combines the clinical liver biochemical parameters with the TNM stage, taking into account anatomy and basic liver biochemical conditions, and more accurately predicts patients 1-OS, 3-OS, and 5-OS. Simultaneously, the decision curve showed that the nomogram in predicting OS is better than that of TNM staging system in all range.

There are also some shortcomings in our research. First, the nomogram was created based on data obtained from only one institution in China, lacking multi-center research data. Second, more patients are needed in the primary and validation cohorts. Finally, in the validation cohort, the follow-up time was shorter, and patients in the validation cohort still needed close monitoring and 5-year follow-up data. In addition, future research can incorporate the HBsAg-positive patient’s quality of life into the research system, and the nutritional status and quality of life of HBsAg-positive patients during the survival period have the same important status as the prolonged survival time. Despite these limitations, this nomogram represents a prognostic effect on patients with HBsAg-positive GC. We anticipate that this nomogram will stimulate ongoing research that will lead to improvements and access to a larger number of effective methods of prediction becomes available.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we have developed a robust prognostic nomogram to predict the 3- and 5-year OS in patients with HBsAg-positive GC. This nomogram represents an improvement in prognostication over the current TNM stage. The proposed nomogram in this study provided statistically significantly better discrimination than the current TNM stage. To generalize the use of this nomogram in other groups, additional validation with data from other institutions is required.

Abbreviations

- GC:

-

gastric cancer

- LFT:

-

liver function tests

- ALT:

-

alanine aminotransferase

- AST:

-

aspartate aminotransferase

- LDH:

-

lactate dehydrogenase

- GGT:

-

gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase

- TBA:

-

total bile acid

- ALP:

-

alkaline phosphatase

- ALB:

-

albumin

- TBIL:

-

total bilirubin

- ApoA1:

-

apolipoprotein A1

- ApoB:

-

apolipoprotein B

- PT:

-

prothrombin time

- Fbg:

-

fibrinogen

- HBV:

-

hepatitis B virus

- HR:

-

hazard ratio

- 95% CI:

-

95% confidence interval

- OS:

-

overall survival

References

Duarte HO, Gomes J, Machado JC, Reis CA. Gastric cancer: Basic aspects. Helicobacter. 2018;23(Suppl 1):e12523.

El-Serag HB. Epidemiology of viral hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(6):1264–73.

Wei XL, Qiu MZ, Jin Y, Huang YX, Wang RY, Chen WW, Wang DS, Wang F, Luo HY, Zhang DS, et al. Hepatitis B virus infection is associated with gastric cancer in China: an endemic area of both diseases. Br J Cancer. 2015;112(7):1283–90.

Jiang XF, Tang QL, Zou Y, Xu L, Zeng H, Chi C, Jiang JR, Zhang BZ. Does HBV infection increase risk of endometrial carcinoma? Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15(2):713–6.

Ye YF, Xiang YQ, Fang F, Gao R, Zhang LF, Xie SH, Liu Z, Du JL, Chen SH, Hong MH, et al. Hepatitis B virus infection and risk of nasopharyngeal carcinoma in southern China. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24(11):1766–73.

Wei XL, Luo HY, Li CF, Jin Y, Zeng ZL, Ju HQ, Wu QN, Wang Y, Mao MJ, Liu WL, et al. Hepatitis B virus infection is associated with younger median age at diagnosis and death in cancers. Int J Cancer. 2017;141(1):152–9.

van den Broek MA, Olde DS, Dejong CH, Lang H, Malago M, Jalan R, Saner FH. Liver failure after partial hepatic resection: definition, pathophysiology, risk factors and treatment. Liver Int. 2008;28(6):767–80.

Mahar AL, Zagorski B, Kagedan D, Dixon M, El-Sedfy A, Vasilevska-Ristovska J, Cortinovis D, Rowsell C, Law C, Helyer L, et al. Evaluating TNM stage prognostic ability in a population-based cohort of gastric adenocarcinoma patients in a low-incidence country. Can J Public Health. 2018;109(4):480–8.

Ye J, Ren Y, Wei Z, Hou X, Dai W, Cai S, Tan M, He Y, Yuan Y. External validation of a modified 8th AJCC TNM system for advanced gastric cancer: long-term results in southern China. Surg Oncol. 2018;27(2):146–53.

Amin MB, Greene FL, Edge SB, Compton CC, Gershenwald JE, Brookland RK, Meyer L, Gress DM, Byrd DR, Winchester DP. The eighth edition AJCC cancer staging manual: continuing to build a bridge from a population-based to a more “personalized” approach to cancer staging. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(2):93–9.

In H, Solsky I, Palis B, Langdon-Embry M, Ajani J, Sano T. Validation of the 8th edition of the AJCC TNM staging system for gastric cancer using the national cancer database. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24(12):3683–91.

Jiao XG, Deng JY, Zhang RP, Wu LL, Wang L, Liu HG, Hao XS, Liang H. Prognostic value of number of examined lymph nodes in patients with node-negative gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(13):3640–8.

Mita MT, Marchesi F, Cecchini S, Tartamella F, Ricco’ M, Abongwa HK, Roncoroni L. Prognostic assessment of gastric cancer: retrospective analysis of two decades. Acta Biomed. 2016;87(2):205–11.

Camp RL, Dolled-Filhart M, Rimm DL. X-tile: a new bio-informatics tool for biomarker assessment and outcome-based cut-point optimization. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(21):7252–9.

Kamangar F, Dores GM, Anderson WF. Patterns of cancer incidence, mortality, and prevalence across five continents: defining priorities to reduce cancer disparities in different geographic regions of the world. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(14):2137–50.

Moore MA, Eser S, Igisinov N, Igisinov S, Mohagheghi MA, Mousavi-Jarrahi A, Ozenturk G, Soipova M, Tuncer M, Sobue T. Cancer epidemiology and control in North-Western and Central Asia—past, present and future. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2010;11(Suppl 2):17–32.

Dehesa-Violante M, Nunez-Nateras R. Epidemiology of hepatitis virus B and C. Arch Med Res. 2007;38(6):606–11.

Lee MH, Yang HI, Liu J, Batrla-Utermann R, Jen CL, Iloeje UH, Lu SN, You SL, Wang LY, Chen CJ. Prediction models of long-term cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma risk in chronic hepatitis B patients: risk scores integrating host and virus profiles. Hepatology. 2013;58(2):546–54.

Kirchner GI, Beil W, Bleck JS, Manns MP, Wagner S. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori and occurrence of gastroduodenal lesions in patients with liver cirrhosis. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2011;4(1):26–31.

Zullo A, Romiti A, Tomao S, Hassan C, Rinaldi V, Giustini M, Morini S, Taggi F. Gastric cancer prevalence in patients with liver cirrhosis. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2003;12(3):179–82.

Kim SG, Seo HS, Lee HH, Song KY, Park CH. Comparison of the differences in survival rates between the 7th and 8th editions of the AJCC TNM staging system for gastric adenocarcinoma: a single-institution study of 5,507 patients in Korea. J Gastric Cancer. 2017;17(3):212–9.

Mackillop WJ, Quirt CF. Measuring the accuracy of prognostic judgments in oncology. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50(1):21–9.

Barchi LC, Yagi OK, Jacob CE, Mucerino DR, Ribeiro U, Marrelli D, Roviello F, Cecconello I, Zilberstein B. Predicting recurrence after curative resection for gastric cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol EJSO. 2016;42(1):123–31.

Authors’ contributions

YH, MJM and WJS contributed equally to this manuscript. XPW and LZ designed the experiments; ZLH collected data; MJM and WJS analyzed data; MJM and LZ provided research materials and methods; YH and XPW wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff of the biochemical laboratory of Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center who provided various biochemical markers, and all of the staff who supported our study.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

Due to ethical restrictions, the raw data underlying this paper are available upon request to the corresponding author.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Written informed consent for the use of plasma and serum samples was obtained from all GC patients. This study was approved by the Institute Research Ethics Committee of the Sun Yat-Sen University Cancer Center, Guangzhou, China.

Funding

There are no funding worked in our manuscript.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

He, Y., Mao, M., Shi, W. et al. Development and validation of a prognostic nomogram in gastric cancer with hepatitis B virus infection. J Transl Med 17, 98 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-019-1841-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-019-1841-3