Abstract

Background

Serous chorioretinopathy has been associated with MEK inhibitors, including cobimetinib. We describe the clinical features of serous retinopathy observed with cobimetinib in patients with BRAF V600-mutated melanoma treated in the Phase III coBRIM study.

Methods

In the coBRIM study, 493 patients were treated in two randomly assigned treatment groups: cobimetinib and vemurafenib (n = 247) or vemurafenib (n = 246). All patients underwent prospective ophthalmic examinations at screening, at regular intervals during the study, and whenever ocular symptoms developed. Patients with serous retinopathy were identified in the study database using a group of relevant and synonymous adverse event terms.

Results

Eighty-six serous retinopathy events were reported in 70 patients (79 events in 63 cobimetinib and vemurafenib-treated patients vs seven events in seven vemurafenib-treated patients). Most patients with serous retinopathy identified by ophthalmic examination had no symptoms or had mild symptoms, among them reduced visual acuity, blurred vision, dyschromatopsia, and photophobia. Serous retinopathy usually occurred early during cobimetinib and vemurafenib treatment; median time to onset was 1.0 month. Most events were managed by observation and continuation of cobimetinib without dose modification and resolved or were resolving by the data cutoff date (19 Sept 2014).

Conclusions

Cobimetinib treatment was associated with serous retinopathy in patients with BRAF V600-mutated melanoma. Retinopathy was generally asymptomatic or mild. Periodic ophthalmologic evaluations at regular intervals and at the manifestation of any visual disturbance are recommended to facilitate early detection and resolution of serous retinopathy while patients are taking cobimetinib.

Trial Registration Clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01689519). First received: September 18, 2012

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Aberrant activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway is commonly observed in human cancers [1]. Approximately 50% of cutaneous melanomas harbor mutations in the BRAF gene, resulting in constitutive activation of the MAPK pathway [2, 3]. Combined BRAF and MEK inhibition enhances antitumor activity and may prevent or delay development of acquired resistance by providing more potent inhibition of the MAPK pathway [4, 5]. In the coBRIM study, the combination of cobimetinib, a MEK inhibitor, with vemurafenib, a BRAF inhibitor, significantly improved progression-free survival (PFS) [6] and overall survival (OS) [7] compared with placebo and vemurafenib (hereafter referred to as vemurafenib) in advanced BRAF V600-mutated melanoma.

A unique ocular adverse event (AE) resembling central serous retinopathy has been described with MEK inhibitors [4, 8,9,10,11,12,13]. MEK-associated serous retinopathy manifests bilaterally within days after inhibitor initiation [9, 12, 14]. Patients may present with blurred or impaired vision, but many have no symptoms, with problems detected on ophthalmologic examination [9, 11]. Funduscopic examination reveals a blunted foveal light reflex and often multiple foveal lesions [9]. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) is used to detect bilateral subfoveal neurosensory retinal detachments not associated with fluorescein angiography or indocyanine green angiography, indicating unremarkable chorioretinal vasculature [9, 12].

In contrast, classic central serous retinopathy commonly manifests as unilateral metamorphopsia in middle-aged men, frequently associated with recent corticosteroid use or psychological stress [12, 15]. On funduscopic examination, typical findings include round, well-delineated, shallow, serous macular neurosensory detachment, often surrounded by a halo light reflex. Vascular abnormalities are usually found on fluorescein and indocyanine green angiography, exhibiting single or multiple discrete leakage points that evenly distribute dye throughout the subretinal fluid [15]. OCT reveals neurosensory detachment in addition to any associated retinal pigment epithelium detachment. The condition is typically self-limiting, and recovery of visual acuity is usually observed within 1–4 months without the need for treatment [15].

It is clear that the pathophysiology of MEK inhibitor-associated serous retinopathy is distinct from that of classic central serous retinopathy. Therefore, it is important to further define this AE. This article describes the clinical features of serous retinopathy observed with cobimetinib in patients treated in the coBRIM study.

Methods

Study design and treatment

coBRIM was a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, parallel, placebo-controlled Phase III study designed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of cobimetinib combined with vemurafenib, compared with vemurafenib, in patients with BRAF V600 mutation—positive unresectable locally advanced or metastatic melanoma. This trial was registered on clinicaltrials.gov as NCT01689519. The primary end point was investigator-assessed PFS. Secondary end points included OS, objective response rate, duration of response, PFS as assessed by independent review, safety, pharmacokinetics, and health-related quality of life (HRQOL). Complete methodology of the study and primary efficacy and safety results have previously been published and the protocol is available online [6]. The study was approved by the institutional review board or ethics committee at each participating institution and was conducted in accordance with the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference on Harmonisation guidelines for Good Clinical Practice. All the patients provided written informed consent.

Key eligibility criteria were age ≥18 years, histologically confirmed unresectable locally advanced stage IIIC or IV melanoma, BRAF V600 mutation detected using the cobas ® 4800 BRAF V600 Mutation Test (Roche Molecular Systems Inc. USA), no history of systemic therapy for advanced disease, measurable disease according to Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors version 1.1, and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status 0–1. Because of the known ocular toxicities associated with MEK inhibitors, patients with a history or ophthalmic examination evidence of a retinal abnormality considered a risk factor for neurosensory retinal detachment/central serous retinopathy, retinal vein occlusion, or neovascular macular degeneration were excluded. Patients also were excluded if they had risk factors for retinal vein occlusion, including uncontrolled glaucoma with intraocular pressure >21 mmHg, grade ≥2 serum cholesterol, hypertriglyceridemia, or fasting hyperglycemia.

Patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio using an interactive response system [Perceptive Informatics (now Parexel International), USA] to receive oral vemurafenib (960 mg twice daily) in combination with either placebo or oral cobimetinib (60 mg once daily for 21 days followed by 7 days off). Treatment was administered in 28-day cycles and continued until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, or withdrawal of consent. Patients were stratified according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer stage and geographic region. Dose modifications for management of specific adverse events were mandated by the protocol. For grade ≥2 visual symptoms, a complete ophthalmic examination was to be performed and treatment with cobimetinib combined with vemurafenib was to be interrupted until resolution to grade ≤1. Dose reduction of the implicated agent was employed if grade ≥2 visual symptoms recurred. Treatment was to be permanently discontinued in the case of retinal vein occlusion, lack of resolution of visual symptoms to grade ≤1 within 28 days, or recurrence of grade ≥2 visual symptoms despite dose reduction.

Ophthalmic assessments

Complete ophthalmic examinations were performed by a qualified ophthalmologist on all patients at screening and day 1 of cycle 2, then every three cycles until cycle 11, every four cycles until cycle 23, every six cycles thereafter or when clinically indicated during the study, and at the end of study treatment visit (Additional file 1). Examinations included visual acuity testing, intraocular pressure measurements by tonometry, slit-lamp ophthalmoscopy, indirect ophthalmoscopy, and OCT (time or spectral-domain).

Analysis

To ensure collection of all potential events, patients who experienced serous retinopathy were identified using a broad group of preferred terms from the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) (Additional file 2) and record review from ophthalmologic examinations. Events were graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (NCI CTCAE) version 4.0 scale for eye disorders-other (Additional file 3). NCI CTCAE version 4.0 does not have a severity grading scale for serous retinopathy. Results were presented and tabulated with descriptive statistics. The data cutoff date for this analysis was 19 Sept 2014.

Results

Patients

Between January 2013 and January 2014, coBRIM enrolled 495 patients from 135 sites in the United States, Australia, New Zealand, Israel, and Europe. Of 495 randomly assigned patients, one patient in each arm did not receive study treatment (Additional file 4); the remaining 493 received cobimetinib combined with vemurafenib (n = 247) or vemurafenib (n = 246). At the time of data cutoff, the median follow-up duration for all patients was 10.7 months.

Frequency and severity of serous retinopathy events

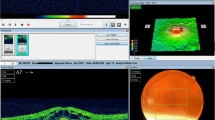

Serous retinopathy occurred in 63 of 247 cobimetinib combined with vemurafenib recipients (26%) (79 events), compared with seven of 246 vemurafenib recipients (3%) (7 events). In the cobimetinib combined with vemurafenib arm, these events were usually reported as chorioretinopathy (49%) and retinal detachment (33%) (Table 1). Serous retinopathy events were characterized by accumulation of subretinal fluid (Fig. 1). Most patients had no symptoms or had mild symptoms (grade 1; see Table 1). Most events were bilateral and were identified by surveillance ophthalmic examination. Grade 3–4 serous retinopathy (Table 1) was identified in seven cobimetinib combined with vemurafenib recipients (11%); symptoms were present in all seven patients and included reduced visual acuity, blurred vision, dyschromatopsia, and photophobia.

Bilateral serous retinopathy (left eye shown) in a 64-year-old woman receiving cobimetinib combined with vemurafenib. At baseline, ophthalmic examination findings were normal, and no retinal abnormalities were detected either on bidimensional near-infrared image of the macula or on cross-sectional optical coherence tomography scan across the fovea (first row). On study day 8, the patient had nonserious grade 2 bilateral blurred vision. On study day 10, ocular examination with indirect ophthalmoscopy revealed bilateral serous subfoveal neurosensory detachment (i.e. subretinal fluid). Retinal imaging showed that detachments of the neurosensory retina were not limited to the fovea but were multiple and extended across the macular area (second and third rows, white arrows). A diagnosis of nonserious grade 2 serous retinopathy was made, and no treatment was administered for this event. On study day 14, the event of neurosensory detachments was considered resolved on indirect ophthalmoscopy, and blurred vision was considered resolved on study day 15. On study day 21, retinal imaging confirmed resolution of the retinal abnormalities (fourth row). The investigator considered blurred vision and serous retinopathy to be related to cobimetinib combined with vemurafenib. Treatment with cobimetinib combined with vemurafenib was permanently discontinued on study day 36 because of other adverse events, including pyrexia, rash, and elevated liver enzyme levels, with consideration of the previous event of serous retinopathy

Baseline characteristics of patients with serous retinopathy in the cobimetinib combined with vemurafenib arm were similar to those of the overall coBRIM population (Table 2). The frequency with which serous retinopathy developed in men and women in the cobimetinib combined with vemurafenib arm was 59% and 41%, respectively; classic serous retinopathy occurs predominantly in men [15].

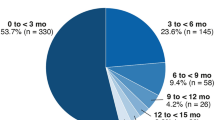

Time to first onset of serous retinopathy

Median time to first onset of serous retinopathy in the cobimetinib combined with vemurafenib arm was 1.0 month (range, 0.1–9.3 months). Most (63%) grade ≥2 events occurred during cycle 1 (Fig. 2).

Management and resolution of serous retinopathy

Most patients with a first serous retinopathy event of grade 1 continued to receive cobimetinib without dose reduction (72%); it resolved in 38% of these patients (Table 3). In patients with grade 2 serous retinopathy (65%), doses were frequently reduced; it resolved in 92% of these patients. Grade 3–4 serous retinopathy was managed by interruption or withdrawal of cobimetinib and was considered resolved or resolving at data cutoff; only one patient needed surgical treatment. This patient had grade 3 idiopathic rhegmatogenous retinal detachment of the right eye considered by the investigator to be unrelated to cobimetinib or vemurafenib. Although clinically distinct from serous retinopathy, it was included with the cases of serous retinopathy because retinal detachment was included in preselected MedDRA preferred terms relevant to serous retinopathy (Additional file 2). This patient underwent pneumatic retinopexy, a surgical treatment for localized rhegmatogenous retinal detachment, and the event was considered resolved on the day of surgery.

Overall, 52% of serous retinopathy events in the cobimetinib combined with vemurafenib arm had resolved at data cutoff. Of the resolved events, median time to resolution was 1.2 months (range, 0.2–10.3 months).

Recurrent serous retinopathy

Fourteen patients with recurrent serous retinopathy were in the cobimetinib and vemurafenib arm. One patient experienced three recurrent episodes; the remaining 13 experienced one recurrence each.

Most subsequent events were of the same or milder grade than the initial event; however, in three patients, initial and recurrent events were grade 1 and 2, respectively. No recurrent events were grade ≥3. At the data cutoff date, half the recurrent events had resolved. No pattern emerged of action taken for recurrent events; patients continued taking cobimetinib combined with vemurafenib, therapy was interrupted, or therapy was withdrawn (four patients).

Discussion

This article describes clinical characteristics of serous retinopathy in patients treated with cobimetinib combined with vemurafenib in the coBRIM study. Because all patients were prospectively screened for visual disturbances throughout the study, per protocol, most events were diagnosed early in the course of treatment, and most patients had no or mild symptoms at diagnosis.

The clinical relevance of surveillance ophthalmic examinations is unclear. Most patients with serous retinopathy had no symptoms, did not require drug discontinuation or dose alteration, and did not experience greater severity of the condition over time. Patients with mildly symptomatic (grade 2) serous retinopathy had dose reduction, resulting in resolution in the majority. For all but one patient (rhegmatogenous retinal detachment) with grade ≥3 serous retinopathy, dose interruption or withdrawal led to improvement without surgery. Few patients experienced recurrence despite continuing or restarting cobimetinib. All recurrent serous retinopathy events were either asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic, and half resolved by the time of data cutoff.

Based on the limited scientific literature available, characteristics of serous retinopathy observed with cobimetinib were similar to those of retinal changes observed with other MEK inhibitors [9, 11, 12, 14], suggesting that this is a class effect [11]. Symptomatic ocular toxicity, most commonly blurred vision, has been reported in 0–17% of patients treated with single-agent MEK inhibitors [16], whereas blurred vision and chorioretinopathy were reported in 0–2% and 1% of patients, respectively, treated with the combination of trametinib and dabrafenib [17, 18]. Higher incidences of ocular toxicity have been observed in trials incorporating prospective screening, but the reported events are frequently asymptomatic. Prospective screening identified retinopathy in 59% of patients treated with binimetinib, alone or in combination with RAF265 or encorafenib, with symptomatic events reported in 25% of patients [9], and 26% of patients treated with cobimetinib combined with vemurafenib in the current study, with symptomatic (grade ≥ 2) events in 12% of patients. Given the lack of prospective screening for retinopathy in other trials, incidence cannot be compared across MEK inhibitors. Because of a lack of randomized trials and differences in the description and reporting of ocular toxicity across trials, it is unclear whether the combination of a BRAF inhibitor with a MEK inhibitor alters the incidence of ocular toxicities compared with MEK inhibitor monotherapy. However, in one small study, addition of the pan-RAF inhibitor RAF265 or the selective BRAF inhibitor encorafenib to the MEK inhibitor binimetinib did not appear to influence the incidence of retinopathy [9]. Furthermore, anecdotal data with binimetinib suggest a temporal relationship between ocular toxicity and dose administration/blood binimetinib levels [9]. Further research is necessary to determine whether a similar relationship exists for other MEK inhibitors.

Although the MAPK pathway seems to play an important role in maintenance, protection, and repair of the retina, pathophysiologic mechanisms underlying MEK inhibitor-induced retinopathy are not well understood [11]. The retinal pigment epithelium forms the outer component of the blood–retina barrier and controls solute and fluid permeability, a function critical for maintenance of the specialized environment of the neural retina [19]; fluid accumulation between these layers can result in retinal detachment [11]. There is evidence that MAPK signaling regulates density of fluid transport channels (aquaporins) between retinal pigment epithelial cells [20]. Thus, MEK inhibition may alter permeability of the retinal pigment epithelium, allowing accumulation of subretinal fluid. Further study is needed to test this hypothesis.

In other retinal diseases, the long-term presence of subretinal fluid can lead to photoreceptor death and permanent vision loss; therefore, persistent events may warrant treatment [15]. Understanding of the pathogenesis of classic central serous chorioretinopathy emphasizes the role of the choroid, which seems to be extremely permeable in this disease [15]. However, chorioretinal abnormalities are not observed in MEK inhibitor-associated serous retinopathy, in which pathophysiology seems to result instead from altered permeability of the retinal pigment epithelium. Therefore, treatments that might promote subretinal fluid resolution in classic central serous chorioretinopathy [15] may not be useful for subretinal fluid resolution in MEK inhibitor-associated serous retinopathy. It is reassuring that almost all cases of MEK inhibitor-associated serous retinopathy in the coBRIM study ultimately resolved either spontaneously or through dose modification.

In our experience, management of cobimetinib-associated serous retinopathy necessitates close collaboration with an ophthalmologist, and early involvement should be considered because most events occur within 1 month of treatment initiation. However, prospective screening is probably not warranted because surveillance ophthalmologic examination typically identifies asymptomatic serous retinopathy. Ophthalmologic examination should be performed periodically during cobimetinib treatment and as necessary for new or worsening visual disturbances. Temporarily withholding or reducing the dose of cobimetinib should be considered upon diagnosis of serous retinopathy.

There are several limitations to our results. First, reliance on AE reporting rather than ophthalmic (OCT) confirmation might have resulted in underreporting of asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic cases. Second, ophthalmic images were not prospectively centrally reviewed. Third, visual acuity was not measured in a standardized fashion across sites. Despite these limitations, the large difference in rates of serous retinopathy between the cobimetinib combined with vemurafenib arm and the vemurafenib arm make it unlikely that results were caused by study limitations rather than the real effects of MEK inhibition with cobimetinib.

Conclusion

This report provides context around the guidance for the management of serous retinopathy in patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma with a BRAF V600E or V600K mutation receiving cobimetinib in combination with vemurafenib. Cobimetinib in combination with vemurafenib was associated with serous retinopathy in 26% of patients with BRAF V600-mutated melanoma. Although retinopathy was generally asymptomatic or mild and although most affected patients could safely continue to receive cobimetinib, dose interruption and dose reduction should be considered. Patients receiving cobimetinib should undergo ophthalmologic examination at regular intervals and whenever they experience symptoms suggestive of serous retinopathy. Additional examination may be warranted if symptoms persist. Guidance on the management of MEK-associated serous retinopathy can be found in the local prescribing information where cobimetinib is approved.

Abbreviations

- MAPK:

-

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- PFS:

-

progression-free survival

- OS:

-

overall survival

- AE:

-

adverse event

- OCT:

-

optical coherence tomography

- HRQOL:

-

health-related quality of life

- MedDRA:

-

Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities

- NCI CTCAE:

-

National Cancer Institute Common Terminology for Adverse Events

References

Zhao Y, Adjei AA. The clinical development of MEK inhibitors. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2014;11(7):385–400.

Davies H, Bignell GR, Cox C, Stephens P, Edkins S, Clegg S, et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature. 2002;417(6892):949–54.

Curtin JA, Fridlyand J, Kageshita T, Patel HN, Busam KJ, Kutzner H, et al. Distinct sets of genetic alterations in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(20):2135–47.

Ribas A, Gonzalez R, Pavlick A, Hamid O, Gajewski T, Daud A, et al. Combination of vemurafenib and cobimetinib in patients with advanced BRAF V600-mutated melanoma: a phase 1b study. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(9):954–65.

Long GV, Stroyakovskiy D, Gogas H, Levchenko E, de Braud F, Larkin J, et al. Combined BRAF and MEK Inhibition versus BRAF inhibition alone in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(20):1877–88.

Larkin J, Ascierto PA, Dréno B, Atkinson V, Liszkay G, Maio M, et al. Combined vemurafenib and cobimetinib in BRAF-mutated melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(20):1867–76.

Atkinson V, Larkin J, McArthur GA, Ribas A, Ascierto PA, Liszkay G, et al. Improved overall survival (OS) with cobimetinib (COBI)+ vemurafenib (V) in advanced BRAF-mutated melanoma and biomarker correlates of efficacy. 12th International Congress of the Society for Melanoma Research, November 18-21, San Francisco, CA; 2015. http://www.roche.com/dam/jcr:b7f64a44-c724-4b2b-8976-9f33954f1492/en/med-cor-2015-11-23-e.pdf.

Infante JR, Fecher LA, Falchook GS, Nallapareddy S, Gordon MS, DeMarini DJ, et al. Safety, pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic, and efficacy data for the oral MEK inhibitor trametinib: a phase 1 dose-escalation trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(8):773–81.

Urner-Bloch U, Urner M, Stieger P, Galliker N, Winterton N, Zubel A, et al. Transient MEK inhibitor-associated retinopathy in metastatic melanoma. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(7):1437–41.

Weekes CD, Von Hoff DD, Adjei AA, Leffingwell DP, Eckhardt SG, Gore L, et al. Multicenter phase I trial of the mitogen-activated protein kinase 1/2 inhibitor BAY 86-9766 in patients with advanced cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(5):1232–43.

van der Noll R, Leijen S, Neuteboom GHG, Beijnen JH, Schellens JHM. Effect of inhibition of the FGFR-MAPK signaling pathway on the development of ocular toxicities. Cancer Treat Rev. 2013;39(6):664–72.

McCannel TA, Chmielowski B, Finn RS, Goldman J, Ribas A, Wainberg ZA, et al. Bilateral subfoveal neurosensory retinal detachment associated with MEK inhibitor use for metastatic cancer. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014;132(8):1005–9.

Houde N, Faivre SJ, Awada A, Raymond E, Italiano A, Besse-Hammer T, et al. Safety and evidence of activity of MSC1936369, an oral MEK1/2 inhibitor, in patients with advanced malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:abstr 3019.

Schoenberger SD, Kim SJ. Bilateral multifocal central serous-like chorioretinopathy due to MEK inhibition for metastatic cutaneous melanoma. Case Rep Ophthalmol Med. 2013;2013:673796.

Nicholson B, Noble J, Forooghian F, Meyerle C. Central serous chorioretinopathy: update on pathophysiology and treatment. Surv Ophthalmol. 2013;58(2):103–26.

Duncan KE, Chang LY, Patronas M. MEK inhibitors: a new class of chemotherapeutic agents with ocular toxicity. Eye (Lond). 2015;29(8):1003–12.

Long GV, Stroyakovskiy D, Gogas H, Levchenko E, deBraud F, Larkin J, et al. Dabrafenib and trametinib versus dabrafenib and placebo for Val600 BRAF-mutant melanoma: a multicentre, double-blind, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;386(9992):444–51.

Robert C, Karaszewska B, Schachter J, Rutkowski P, Mackiewicz A, Stroiakovski D, et al. Improved overall survival in melanoma with combined dabrafenib and trametinib. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(1):30–9.

Runkle EA, Antonetti DA. The blood-retinal barrier: structure and functional significance. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;686:133–48.

Jiang Q, Cao C, Lu S, Kivlin R, Wallin B, Chu W, et al. MEK/ERK pathway mediates UVB-induced AQP1 downregulation and water permeability impairment in human retinal pigment epithelial cells. Int J Mol Med. 2009;23(6):771–7.

Authors’ contributions

LCM, LG, JJG, AV, JL, GM, AR, TE, AGE, and BD conceived the study and wrote the manuscript. GB, SE, JS, and AU analyzed the clinical data. All authors critically reviewed the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the participating investigators, patients, and current and past members of the Roche and Genentech cobimetinib and vemurafenib teams. Third-party medical writing assistance was funded by F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd. and provided by Melanie Sweetlove, MSc, and Jennifer M. Kulak, PhD (ApotheCom, San Francisco, CA). Cobimetinib is being developed by Genentech, a member of the Roche Group, under a collaboration agreement with Exelixis. Vemurafenib is being developed by Genentech, a member of the Roche Group, under a collaboration agreement with Plexxikon.

Competing interests

This study was supported by F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, and several co-authors are employees of Roche/Genentech (GB, SE, JJH, AU). LC-M has received research funding from, acted as a consultant/advisor for, and received travel funding from Roche. LDG has received honoraria and travel funds from Roche, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and GlaxoSmithKline; and acted as a consultant/advisor to Italfarmaco. JG has received honoraria and travel funds from Roche, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and GlaxoSmithKline; acted as a consultant/advisor to GlaxoSmithKline, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Roche, Amgen, Merck, and Novartis; received research funding from Roche and Bristol-Myers Squibb; and received travel funding from Roche. GAM has received research funding from Pfizer, Celgene, and Ventana; acted as a consultant/advisor for Provectus; and received travel funding from Roche and Novartis. AR has stock or other ownership in Compugen, CytomX, Five Prime, and Kite Pharma; and has worked in a consulting/advisory role with Pfizer, Merck, Amgen, and Roche. PAA has received research funding from Array, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Roche, and Ventana and acted as a consultant/advisor to Amgen, Array, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Roche, and Ventana. TRJE has served on advisory boards for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Baxter, Clovis, Eisai, GlaxoSmithKline, Celgene, Bayer, Roche, Genentech, Otsuka, and Karus Therapeutics; consulted for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Clovis, Baxter, GlaxoSmithKline, Eisai, Roche, Genentech, and Karus Therapeutics; received research funding from Astra Zeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Baxter, Bayer, Clovis, Celgene, Eisai, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Otsuka, Roche Genentech, Merck, Verastem, Vertex, Immunocore, Basilea, Lilly, and Pharmamar; been on speakers bureaus for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, GlaxoSmithKline, Roche, and Bayer; and received travel funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb and Celgene. AG-E, AV, and JL have no competing interests. BD has received research funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb and GlaxoSmithKline; worked in a consulting/advisory role for Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Roche, and Novartis; been on speakers’ bureaus for Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, and Roche; and received travel funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb and Roche.

Consent for publication

All the patients provided written informed consent.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the institutional review board or ethics committee at each participating institution and was conducted in accordance with the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference on Harmonisation guidelines for Good Clinical Practice. All the patients provided written informed consent.

Funding

F. Hoffmann–La Roche/Genentech sponsored the study. The primary analysis of this study (NCT01689519) was previously published by Larkin et al. [6]. Authors and their research teams were involved in the collection of data. Representatives of the sponsor collated the data and confirmed the accuracy of the data and analysis. The analysis was performed in collaboration with the authors. All the authors had full access to the data and analyses presented in this report.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

de la Cruz-Merino, L., Di Guardo, L., Grob, JJ. et al. Clinical features of serous retinopathy observed with cobimetinib in patients with BRAF-mutated melanoma treated in the randomized coBRIM study. J Transl Med 15, 146 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-017-1246-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-017-1246-0