Abstract

Objectives

The current literature lacks a detailed and standardised description of public health knowledge translation (KT) activities designed to be applied at local levels of health systems. As part of an ongoing research project called the Transfert de connaissances en regions (TC-REG project), we aim to develop a local KT taxonomy in the field of health prevention by means of a participative study between researchers, decision-makers and field professionals. This KT taxonomy provides a comparative description of existing local health prevention KT strategies.

Methods

Two methods were used to design a participative process conducted in France to develop the taxonomy, combining professional meetings (two seminars) and qualitative interviews. The first step involved organising a seminar in Paris, attended by health prevention professionals from health agencies in four regions of France and regional non-profit organisations for health education and promotion. This led to the drafting of regional KT plans to be implemented in the four regions. In a second step, we conducted interviews to obtain a clear understanding of the KT activities implemented in the regions. Based on data from interviews, a KT taxonomy was drawn up and discussed during a second seminar.

Results

Our work resulted in a KT taxonomy composed of 35 standardised KT activities, grouped into 11 categories of KT activities, e.g. dissemination of evidence, support for use of evidence through processes and structures, KT advocacy, and so on.

Conclusions

The taxonomy appears to be a promising tool for developing and evaluating KT plans for health prevention in local contexts by providing some concrete examples of potential KT activities (advocacy) and a comparison of the same activities and their outcomes (evaluation).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Emerging evidence points to a consensual need for more evidence-informed public health knowledge translation (KT) practices given the opportunities arising from this kind of approach, e.g. improvement in the efficiency, credibility and sustainability of health systems [1]. In France, the Transfert de connaissances en regions (Regional knowledge transfer or the TC-REG) project was set up in order to enhance evidence-based practices within a specific field, namely that of local health prevention policies. The TC-REG protocol has already been published [2]. Briefly, TC-REG is a comparative multiple case study of a KT plan in the field of health prevention, based on a realistic approach [3, 4]. The project is designed to introduce activities aimed at improving the conversion of research-based knowledge into health prevention-related decision-making and practices in four regions in France and to assess their impact through a realistic evaluation [2]. While the process of converting research-based knowledge into decision-making and practice has been given several names in the literature [5, 6] (Table 1 details the different terms), we adopt the most commonly used term, namely, KT. The National Public Health Institute of Quebec defines KT as “the group of activities and interaction mechanisms that foster the dissemination, adoption and appropriation of the most up-to-date knowledge possible for use in professional practice and in healthcare management” [7].

Many scholars have highlighted the challenge of converting research-based knowledge into evidence-informed practices and decision-making in the public health field [8, 9]. First, barriers linked to people, organisations, contexts and properties of the evidence persist [10,11,12], preventing the optimal production and use of evidence [13,14,15]. Second, the literature on KT provides many frameworks and taxonomies [16,17,18,19], but these are not always adapted to the needs and practices of health prevention professionals, including decision-makers. Indeed, most of them deal with generalist frameworks, such as those described by Milat et al. [20] (e.g. KTA and PARISH), omitting to mention some KT specific activities or whether any taxonomies exist for them. These generalist frameworks are mostly (1) healthcare focused (e.g. nursing, obesity treatment) [21, 22], (2) patient focused [23], (3) strategy focused [22] or (4) objective or mechanism focused [22, 24] (e.g. healthcare professionals’ practices are validated and the criteria are therefore patient oriented only, whereas health prevention requires a more comprehensive approach, including practices that help identify and determine solutions to address potential barriers to evidence-based practice). We can nonetheless mention two major studies that highlight some evidence-based activities [12, 25] in KT. These studies are very helpful to clarify concepts and define methods but, after review, present strategies that are not always adapted to local contexts nor to the field of health prevention outside the care setting. Indeed, the field presents several characteristics that are different from care settings, that is, there is not always clear evidence of practices, the actions and policies are often performed by non-profit organisations, and professionals or volunteers working in these organisations are not always trained in evidence-based practices and they work with few resources. It was also difficult to use both studies in TC-REG without specific appropriation by stakeholders in the different settings or the identification of specific activities, recognised as effective and feasible on the ground. Moreover, the activities need to be specifically described to ensure that they are indeed the activities described in the taxonomy. In effect, we observed that this field of health prevention often uses different terms to describe the same activities (with potentially the same effect) or else the same term is used to talk about different activities (with potentially different effects). Moreover, some activities, such as training, methodological support and knowledge brokering, can be described with the same words in different frameworks, when in fact they are different activities that trigger different mechanisms. For instance, a short training course may only raise awareness of the interest of evidence-based decision-making, while long training courses can include skills for analysing and transferring evidence-based action. The former can enhance the incentive to use evidence, while the latter can provide the skills required to apply it. In this paper, we describe an empirical process we adopted to develop a KT taxonomy that helps to clarify variations in potential KT activities in local health prevention policies. We used a participative approach between researchers, decision-makers and field professionals involved in the KT research project TC-REG. TC-REG, which is still ongoing, began in 2017 and is designed to assess a KT plan to improve policy-making and practices for implementing health prevention in French regions [2]. We argue that this kind of taxonomy can provide operational guidance to local health authorities in order to implement, evaluate and compare KT activities in the field of local health prevention and thus strengthens the evidence in this field.

Methods

The TC-REG study

The TC-REG study aims to test and characterise the facilitators that enable public health stakeholders to address the challenges of KT, incorporating academic health prevention knowledge into policy and practice. To this end, we developed a participatory study that involved participants as co-researchers. This means that all the different stakeholders are involved at all stages, including in their development. The participants were those whose work informed the research and who had an influence over the research process. Thus, decision-makers from regional health agencies (Agence Régionale de Santé; ARS) and field professionals from non-profit organisations (Instance Régionale d’Education et de Promotion de la Santé (Regional Authority of Education and Health Promotion); IREPS) were involved in the study. ARS are responsible for policy-making and health prevention policies. IREPS, which are non-profit organisations, develop health promotion and health prevention programmes and provide methodological support to field professionals in the implementation of health prevention schemes in different settings (e.g. workplaces, schools, care settings, recreation and community centres, rural and urban areas). ARS and IREPS work together to implement health prevention and health policies in local contexts. The TC-REG plan has been rolled out in four French regions to date.

Study design

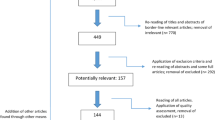

The aim was to develop a taxonomy for a KT plan in the field of local health prevention. This study is embedded in the TC-REG research project and unfolds in two stages. First, we organised a seminar with ARS and IREPS professionals involved in the TC-REG project. This was designed to identify the most feasible and best KT activities to implement in the four regions involved in the project (Step 1). The activities selected were embedded in four KT plans adapted to local contexts, one per region, over 12 months. Interviews were then conducted in the regions to assess the nature and purpose of the activities currently in place as precisely as possible in order to enhance evidence-based decision-making/action. Informed by these data, a KT taxonomy was subsequently developed (Step 2).

Step 1: Seminar with ARS and IREPS professionals to develop contextualised KT plans

Preparing the seminar

To prepare the seminar, in addition to the literature presented in the discussion, we analysed a major piece of evidence [25] published in 2016. We chose it because it is relatively recent and combines a systematic review of the evidence-informed decision-making (EIDM) literature and an extensive review of the research reported in the broader social science literature.

The aim of the study was to identify effective strategies to overcome barriers to EIDM that would fit in with our own aims. The first part was designed to identify the best ways to increase EIDM, while the second part identified insights from social science knowledge to support its use. the authors grouped the interventions reviewed in accordance with six processes by which EIDM might be achieved [25], namely (1) awareness, defined as building awareness of and positive attitude toward EIDM; (2) agreement, defined as building mutual understanding and agreement on policy-relevant issues and the kind of evidence needed to resolve them; (3) communication and access, defined as providing communication of and access to evidence; (4) interaction, defined as interaction between decision-makers and researchers; (5) skills, defined as supporting decision-makers to develop skills in accessing and making sense of evidence; and (6) structure and process, defined as influencing decision-making structures and processes.

We performed an analysis of these studies in order to identify the conditions of KT intervention effectiveness and the expected outcomes of each intervention. This analysis, based on a common framework, was processed independently by three researchers. The findings were compared and discussed by the three researchers in two meetings until consensus was reached. Thus, for each intervention, its definition and description, the conditions of its effectiveness (either by itself or in combination with other interventions), and its influence on the use of evidence were described. The plan was to complement the findings with other sources dedicated to KT interventions in the public health sector at regional or local policy-making and planning level, as presented in the introduction.

Analysis of Langer’ document [25] provided an overview of the effective interventions and categories involved in EIDM. These included a list of effective KT strategies and a list of mechanisms expected to be triggered by them. We grouped the six processes described in Langer’s work [25] into three pragmatic categories of KT activities, as follows: (1) providing access and adaptation of knowledge (pragmatic KT category 1), (2) developing skills and capabilities to analyse, adapt and translate evidence into practice (pragmatic KT category 2), and (3) restructuring working environments to facilitate EIDM (pragmatic KT category 3). For each of these categories, we highlighted the main activities likely to be effective as reported in the work of Langer et al. [25]. In total, nine main activities likely to be effective according to the three categories were presented in the first seminar. The classification is presented in Table 2; the most effective types of activities are also highlighted along with a brief description. Three main activities were considered relevant to providing access to and adaptation of knowledge (pragmatic KT category 1), namely internal and external advocacy, adaptation of communication techniques, and adaptation of dissemination techniques. The most effective types of activity were (1) use of anti-marketing, (2) public segmentation in order to provide appropriate communication, (3) formulation of messages concerning the profit/loss ratio, (4) explanation of uncertainty, (5) use of accounts, records, metaphors and analogies, (6) online media and social networks, (7) labelling strategies, (8) reminders, memory aids, notebooks, and (9) needs-centred communication (Table 2). Two main activities were found to be useful in developing professionals’ skills to analyse, adopt and transfer knowledge into different contexts (pragmatic KT category 2), namely field professional/researcher interactions and training courses. The types of activities that appeared to be most effective were (1) reading clubs, (2) mentoring/guidance to develop evidence-based interventions, (3) training in line with andragogy principles, (4) e-learning, (5) supervision-related training courses, and (6) tailored training content (Table 2). Four activities were found to be useful to improve the organisation and processes in order to facilitate knowledge implementation (pragmatic KT category 3), namely creation/modification of social and professional norms to promote the use of evidence (to make the EIDM the decision-making principle), facilitation, collaboration, and participatory management (Table 2). The types of activities that appeared to be most effective were (1) social marketing techniques, (2) social incentives (norms of use), and (3) facilitation tools (Table 2).

Conducting participative seminars

We then organised the seminar in order to develop a contextualised KT plan for each region based on the best KT activities. The KT plans included KT activities to be implemented and the expected outcomes.

We organised a participative 2-day seminar with the researchers and professionals involved in the TC-REG project with all the ARS and IREPS, each represented by one or two members. In addition, two researchers who were specialists in KT and realistic evaluation were appointed as consultants to support the process. In total, 17 professionals took part.

The seminar was split into four stages based on the participants’ involvement in round tables and working sub-groups. First, the basics of KT processes and tools were presented in order to raise the awareness of participants in the field. This stage provided an opportunity for the regions to describe and talk about the KT initiatives that already existed during a specific round table. In a second stage, certain ‘knowledge documents’ (Stratégies d’Intervention en Prevention, i.e. intervention strategies in health prevention) were presented. The documents were specifically created for the TC-REG project and provide evidence of effective health prevention strategies in five priority areas in France, namely nutrition, alcohol, tobacco smoking, emotional and sexual health, and psychosocial skills [26,27,28,29,30]. The documents are based on systematic reviews and international guidelines. In the third stage, the participants were split into two groups, each from two regions. Based on the two supporting documents drawn up by the most appropriate KT strategies and actions from Langer et al.’s [25] work to implement in French and local contexts, informed by two criteria, the three strategies defined in the preparatory process were combined with the best evidence-based activities. Each group was asked to choose activities from the three categories and to explain the form they could take in different contexts. In the fourth stage, the participants were split into four regional groups and asked to define the activities they would like to and could implement in their own region in accordance with the strategies listed, their needs and resources, and to formulate hypotheses about the effects/outcomes expected in terms of evidence-informed practices. This led us to define four specific KT plans, one per region, describing the activities and expected outcomes adapted to the different health prevention professionals such as IREPS professionals, ARS professionals, stakeholders/field professionals and professionals from advisory organisms involved in implementing regional health policies.

Step 1 was managed by the research team and both guests who were given the KT plans implemented in the four regions by IREPS and ARS during the 12-month health prevention policies and actions period. Figure 1 presents the different stages of step 1.

Step 2: interviews and a second seminar

Some discrepancies arose between the planned process and its realisation in real conditions. Indeed, when the four KT plans were designed during the workshop, the feasibility and sustainability conditions still needed to be substantiated. After the KT plans had been implemented in the regions, it was clear that changes could potentially occur according to the resources and existing local initiatives. Once aware of the potential adjustments in order to know exactly which KT activities had in fact been implemented, the research team conducted a qualitative study 3 months after implementation of the KT plans. This was designed to collect data on the KT activities actually adopted in the regions, including their exact description in order to compare and distinguish them in the TC-REG evaluation.

Ten interviews (two or three per region) and one focus group per region were carried out. The semi-structured interviews were conducted by phone by one researcher, each lasting 50–90 min as, in addition to asking professionals about KT activities adopted in the regions, other aspects of the TC-REG project were also investigated. The focus groups were conducted by the same researcher with the participation of 4–6 professionals from each region. The aim was to obtain a consensus on the data collected during the interviews. The professionals interviewed included project managers and TC-REG referees from both institutions (ARS and IREPS) and all four regions. All of the interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed. The data was analysed by thematic analyses using N’Vivo® software. The analyses yielded a list of KT activities implemented in the four regions. Certain activities were given different names in the different regions but aimed for the same goal with the same implementation process. We grouped them with standardised labels (standardised KT activities) and the standardised activities were then put into categories of KT activities (taxonomy V0).

Finally, to adjust and hone the taxonomy V0, it was first discussed during a second 1-day seminar attended by the researchers (here, the authors), decision-makers and field professionals involved in the TC-REG project. Each activity was discussed to ensure it was (1) clearly distinguishable, (2) really implemented and (3) specific (one activity = one purpose). The round table discussion addressed each activity individually. Minor adjustments (essentially semantic) were made, leading us to define the taxonomy V1. Step 2 provided a first consensually agreed KT taxonomy (taxonomy V1).

Results

Step 1: the contextualised KT plans

Based on the data set out in Table 2 and according to the regional contexts, four KT plans were developed by the ARS and IREPS professionals involved in the TC-REG project, i.e. one contextualised KT plan per region. The KT plans attempted to combine knowledge access and adaptation (pragmatic KT category 1), with some activities designed to develop professionals’ skills in analysing, adopting and transferring knowledge to their different contexts (pragmatic KT category), while improving the organisations and processes in order to facilitate knowledge integration (pragmatic KT category 3). Figure 2 provides an illustration of the KT plan for one region. In this region, for instance, the KT plan targeted four professional publics: professionals from IREPS, professionals from ARS, stakeholders/field professionals, and professionals from the CRSA (Conférence Régionale de la Santé et de l’autonomie – an advisory organism involved in a regional health policies set-up). It included six KT activities implemented with IREPS professionals who targeted five expected outcomes, with nine KT activities implemented with ARS professionals targeting four expected outcomes, six KT activities implemented with stakeholders/field professionals targeting three expected outcomes, and three KT activities implemented with CRSA professionals targeting two expected outcomes (Fig. 2).

Step 2: a consensually agreed KT taxonomy

The qualitative analysis of the interviews and focus group led to the description and reporting of about 10 to 30 KT activities per region. A V0 taxonomy was then established by the research team. Based on this report and during the second 1-day seminar, the taxonomy was presented and discussed with the participants. A slightly adjusted KT taxonomy V1 was consensually adopted by the researchers, stakeholders and decision-makers involved in the TC-REG project. There was a major change to one activity, highlighted during the seminar but performed in none of the four regions, namely, the ‘methodological support for the standardised KT roll-out’ activity (standardised activity 9.5., Table 3). This was added as it is scheduled to be set up by stakeholders after the study. Taxonomy V1 describes 35 standardised KT activities (one standardised activity = one purpose), grouped into 11 categories of KT activities, namely dissemination of evidence; adaptation of evidence; project identification, image and so on, presenting KT processes so as to be visible to the institutions; evidence-dedicated communication; communication on evidence in communications not dedicated to evidence; training in use of evidence; appropriation of evidence; support for evidence use through processes and structures; methodological support for evidence use; co-construction of KT tools; and KT advocacy. The work is presented in Table 3. Table 4 presents the final general taxonomy, completed by a brief description of each of the KT standardised activities.

Discussion

Based on a participative process between researchers, decision-makers and stakeholders, we developed a KT taxonomy composed of 35 standardised KT activities grouped into 11 categories. This taxonomy can now be used in local contexts to help develop and assess KT plans in the field of health prevention. Indeed, it may be used to develop KT plans, distinguish some activities in the evaluation purpose, and help to advocate KT policies in the field of health prevention by providing clear examples of activities for decision-makers.

In the taxonomy, there are the three knowledge transfer strategies recognized as the most effective in the scientific literature [12, 17, 25, 31,32,33,34,35,36]: (1) appropriate access to knowledge, including marketing techniques and reminders (e.g. some activities grouped in the ‘dissemination of evidence’ and ‘adaptation of evidence’ categories), (2) organisation restructuring, including norms and social incentives (e.g. some activities grouped in the ‘communication on evidence in communications not dedicated to evidence’ and ‘support for evidence use through processes and structures’ categories), and (3) stakeholder support (e.g. some activities grouped in the ‘training for evidence use’ and ‘methodological support’ categories). It also fits in with work on different approaches to KT, distinguishing between the knowledge-driven approach (e.g. some activities from the ‘dissemination of evidence’ category), the problem-solving approach (e.g. some activities described in the ‘adaptation of evidence’ and ‘methodological support of evidence use’ categories) and the interactive approach (e.g. some activities from the ‘co-construction of KT tools’ or ‘appropriation of evidence’ categories) [37].

Finally, apart from existing KT frameworks, a wide-ranging review in 2015 identified 51 classification plans for KT interventions to integrate evidence into healthcare practice [20]. They relate to several areas of application (e.g. behavioural change, education, mental health) [38], while only one of them, the classification by Lavis et al. [39], was directly related to KT. This classification has been widely cited in the KT literature [38] and is designed to assess efforts at linking action to research [13, 39]. It distinguishes four clusters of KT activities, namely push efforts (mainly efforts to prepare and communicate evidence briefs to research users and efforts to enhance the capacity of researchers to develop and execute evidence-informed push efforts), efforts to facilitate user-pull (mainly efforts to provide access to research and efforts by researchers to develop research users’ capacity to apply research), user-pull efforts (mainly efforts to facilitate research use and efforts to develop structures and processes to help research users acquire, assess, adapt and apply research), and exchange efforts (including efforts to enhance the capacity of researchers and research users to engage in mutually beneficial partnerships). The framework-like classification provides an overview of KT interventions but lacks consistency when implementing KT plans in local contexts.

In comparison with this classification, the taxonomy we developed is more detailed and provides practical examples of KT activities that can be implemented. The KT activities are adapted to local contexts since they were implemented in the regions before being added to the taxonomy. It should be noted that our taxonomy and the classification by Lavis et al. [39] do not follow the same reasoning, i.e. the standardised KT activities we describe cannot be directly related to any one of the clusters described by Lavis et al. If we take the example of standardised activity 10.1, ‘multidisciplinary development of KT tools and strategies’, this KT activity appears to be simultaneously based on push efforts, efforts to facilitate user-pull, user-pull efforts and exchange efforts, which are complementary. Because this taxonomy is built from the concerns of professionals and describes 35 standardised activities that they know how to implement easily, we argue that it is very relevant to developing KT among professionals. The main added value of the taxonomy is that it provides both content and methods that are easy to implement in local health prevention contexts marked by fewer resources and skills than in other fields (the field of care) or in national policies.

The taxonomy we developed therefore provides practical examples of KT activities, defined in a standardised way, which can help professionals in the field to implement effective KT plans and help evaluators to assess and compare the different activities implemented. The next step in the TC-REG process will be to decide on the best combination of KT activities to support the use of evidence according to local contexts. This work is currently underway, based on a realistic evaluation [2,3,4]. Realistic approaches aim to identify context–mechanism–outcome (CMO) configurations for a given complex intervention, i.e. how the interactions between contexts and interventions activate specific mechanisms to inform outcomes of interest.

In terms of context, two categories need to be distinguished, namely, those directly related to the intervention (i.e. context-related elements of the intervention) and those not related to the intervention (i.e. pre-existing context elements). In the TC-REG study, KT activities implemented in regions are contextual elements directly related to the intervention. On the other hand, data collected to highlight CMO configurations in realistic evaluations remains challenging [40,41,42] – how can we compare the activities conducted with precision? The methodological work presented here enables us to compare the KT plans implemented in the four regions in a standardised manner. It provides a practical example of how contextual data related to the interventions can be collected and standardised according to different settings. Our taxonomising approach can help realistic evaluators to better determine the components required when assessing CMO configurations.

Strengths and limitations

The main strength of this work is the rigorous methodology used to develop the taxonomy. We prepared a seminar based on effective existing KT strategies, supported by the well-known work of Langer et al. [25], which combined systematic and social science reviews. Discussion of the findings between decision-makers and field professionals involved in the TC-REG project helped them to develop and implement KT plans that were adapted to local contexts and based on effective KT strategies. Field data was gathered on the implementation of KT plans, leading to the development of a consensually agreed KT taxonomy between researchers, decision-makers and field professionals working in the health promotion and health prevention sectors in France. Moreover, we adopted a participative and empirical methodology involving researchers and experts in public health and health prevention settings (decision-makers, field professionals and researchers) to make it more robust. The taxonomy we developed was based on data collected after the implementation of evidence-based KT plans, developed through a multidisciplinary approach. Thus, the activities described in the taxonomy are feasible and consider some forms of activity not found in the literature. In addition, the present work provides a useful tool to help professionals from the public health and health prevention sector to develop and evaluate KT plans in local contexts through a precise description of the activities implemented, in line, for example, with behavioural change techniques in another field [43].

However, the work also has some limitations. The first is that the taxonomy was developed in a French and local context. Other strategies may potentially be used at national level, for example, or in other countries where the organisation of professionals in the field of health prevention may be different. We believe that some activities we did not take into consideration may well be implemented elsewhere and could be added to the taxonomy. We are fully aware that other elements could be added, and therefore recommend further research to test its usability in other contexts as well as the most effective combinations of these activities. The second limitation is that, while we could have conducted a systematic review to prepare the seminar, we preferred to use a single, although valuable, summary of such a review for reasons of time and resources. Perhaps other literature reviews could provide further examples of strategies other than those in Langer et al.’s [25] review and these could be included in a future taxonomy.

Conclusion

The work described in this article offers a first step towards developing more evidence-based decision-making and practices in the public health sector. It offers a KT taxonomy built on a participative approach between researchers, field professionals and decision-makers, based on both data from the literature and field practice. On the other hand, it needs further content input if it is to be used internationally. The taxonomy appears to be a promising tool for developing and evaluating KT plans in local contexts in the field of health prevention. The next step is to test its usability in other contexts. In KT research, we argue that this kind of taxonomy could help to provide operational guidance for local health prevention authorities to implement KT strategies and evaluate and compare KT strategies. It also illustrates the determination of CMO configurations that have to be assessed through a realistic assessment. Indeed, this approach develops a consideration of the context of implementation as a key factor. Establishing a taxonomy of these elements allows us to compare specific factors without confusion (different activities using the same term or different terms for the same activity). The next step in TC-REG is to explore the best combinations of these activities, a process that is currently underway.

Availability of data and materials

All the data generated or analysed during this study are included in the paper.

Abbreviations

- ARS:

-

Agence Régionale de Santé

- CMO:

-

Context–Mechanism–Outcomes

- EIDM:

-

evidence-informed decision-making

- IREPS:

-

Instance Régionale d’Education et de Promotion de la Santé; Regional Authority of education and health promotion)

- KT:

-

knowledge translation

- TC-REG:

-

Transfert de connaissances en region, Knowledge translation in regions

References

Alla F, Cambon L. Recherche interventionnelle en santé publique, transfert de connaissances et collaboration entre acteurs, décideurs et chercheurs. Quest Santé Publique. 2014:12;1–4.

Cambon L, Petit A, Ridde V, Dagenais C, Porcherie M, Pommier J, Ferron C, Minary L, Alla F. Evaluation of a knowledge transfer scheme to improve policy making and practices in health promotion and disease prevention setting in French regions: a realist study protocol. Implementation Sci. 2017;12:83.

Pawson R. Evidence-based Policy: A Realist Perspective. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications Ltd; 2006.

Pawson R, Tilley N. Realistic Evaluation. London: Sage Publications Ltd; 1997.

Graham AL, Carpenter KM, Cha S, Cole S, Jacobs MA, Raskob M, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of Internet interventions for smoking cessation among adults. Subst Abus Rehabil. 2016;7:55–69.

McKibbon KA, Lokker C, Wilczynski NL, Ciliska D, Dobbins M, Davis DA, et al. A cross-sectional study of the number and frequency of terms used to refer to knowledge translation in a body of health literature in 2006: a Tower of Babel? Implement Sci. 2010;5:16.

Institut National de Santé Publique du Quebec. Direction de la recherche, formation et développement. Animer un processus de transfert de connaissances et outil d'animation. Quebec : INSPQ; 2009. p. 69.

World Health Organization. Bridging the ‘Know-Do’ Gap. Meeting on Knowledge Translation in Global Health. Geneva: WHO; 2005.

Straus SE, Tetroe J, Graham I. Defining knowledge translation. CMAJ. 2009;181(3–4):165–8.

Gervais M-J, Gagnon F, Bergeron P. Les conditions de mise à profit des connaissances par les acteurs de santé publique lors de la formulation des politiques publiques : L’apport de la littérature sur le transfert des connaissances. Montréal: Chaire d’Etude CJM-IU-UQAM; 2013.

Orton L, Lloyd-Williams F, Taylor-Robinson D, O’Flaherty M, Capewell S. The use of research evidence in public health decision making processes: systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(7):e21704.

Grimshaw JM, Eccles MP, Lavis JN, Hill SJ, Squires JE. Knowledge translation of research findings. Implement Sci. 2012;7:50.

El-Jardali F, Lavis J, Moat K, Pantoja T, Ataya N. Capturing lessons learned from evidence-to-policy initiatives through structured reflection. Health Res Policy Syst. 2014;12:2.

Siron S, Dagenais C, Ridde V. What research tells us about knowledge transfer strategies to improve public health in low-income countries: a scoping review. Int J Public Health. 2015;60(7):849–63.

Dobbins M, Greco L, Yost J, Traynor R, Decorby-Watson K, Yousefi-Nooraie R. A description of a tailored knowledge translation intervention delivered by knowledge brokers within public health departments in Canada. Health Res Policy Syst. 2019;17:63.

Fafard P, Hoffman SJ. Rethinking knowledge translation for public health policy. Evid Policy. 2020;16:165–75. https://doi.org/10.1332/174426418X15212871808802.

Dagenais C, Ridde V, Laurendeau M-C, Souffez K. Knowledge translation research in population health: establishing a collaborative research agenda. Health Res Policy Syst. 2009;7:28.

Bornbaum CC, Kornas K, Peirson L, Rosella LC. Exploring the function and effectiveness of knowledge brokers as facilitators of knowledge translation in health-related settings: a systematic review and thematic analysis. Implement Sci. 2015;10:162.

Milat AJ, Li B. Narrative review of frameworks for translating research evidence into policy and practice. Public Health Res Pract. 2017;27(1).

Lokker C, McKibbon KA, Colquhoun H, Hempel S. A scoping review of classification schemes of interventions to promote and integrate evidence into practice in healthcare. Implement Sci. 2015;10:27.

Dobbins M, Davies B, Danseco E, Edwards N, Virani T. Changing nursing practice: Evaluating the usefulness of a best-practice guideline implementation toolkit. Nurs Leadership. 2005;18:34–45.

Dogherty EJ, Harrison MB, Graham ID. Facilitation as a role and process in achieving evidence-based practice in nursing: a focused review of concept and meaning. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2010;7(2):76–89.

Michie S, Johnston M, Francis J, Hardeman W, Eccles M. From theory to intervention: mapping theoretically derived behavioural determinants to behaviour change techniques. Appl Psychol. 2008;57(4):660–80.

Walter I, Nutley S, Davies H. Developing a taxonomy of interventions used to increase the impact of research. Research Unit for Research Utilisation, Department of Management. St Andrews: University of St. Andrews; 2003.

Langer L, Tripney J, Gough D. The science of using science: researching the use of research evidence in decision-making. London: Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre; 2016.

Chaire de Recherche en prévention des cancers INCa/IReSP/EHESP. SIPrev Tabac. Synthèse d’interventions probantes en réduction du tabagisme des jeunes. 2017. http://www.frapscentre.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/SIPRev-Tabac-VF-GLOBAL.pdf. Accessed 27 Feb 2020.

Chaire de Recherche en prévention des cancers INCa/IReSP/EHESP. SIPrev Nutrition. Synthèse d’interventions probantes dans les domaines de la nutrition. 2017. http://www.frapscentre.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/SIPrev-Nutrition-VF-GLOBAL.pdf. Accessed 27 Feb 2020.

Chaire de Recherche en prévention des cancers INCa/IReSP/EHESP. SIPrev Compétences PsychoSociales. Synthèse d’interventions probantes pour le développement des compétences psychosociales. 2017. http://www.frapscentre.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/SIPREV-CPS-VF-GLOBAL.pdf. Accessed 27 Feb 2020.

Chaire de Recherche en prévention des cancers INCa/IReSP/EHESP. SIPrev Vie Affective et Sexuelle. Synthèse d’interventions probantes relatives à la contraception et la vie affective et sexuelle chez les jeunes. 2017. http://www.frapscentre.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/SIPRev-VAES-GLOBAL.pdf. Accessed 27 Feb 2020.

Chaire de Recherche en prévention des cancers INCa/IReSP/EHESP. SIPrev Alcool. Synthèse d’interventions probantes pour réduire la consommation nocive d’alcool et ses conséquences. 2017. http://www.frapscentre.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/SIPrev-Alcool-VF-GLOBAL.pdf. Accessed 27 Feb 2020.

LaRocca R, Yost J, Dobbins M, Ciliska D, Butt M. The effectiveness of knowledge translation strategies used in public health: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:751.

Brownson RC, Fielding JE, Maylahn CM. Evidence-based public health: a fundamental concept for public health practice. Annu Rev Public Health. 2009;30:175–201.

Bowen S, Erickson T, Martens PJ, Crockett S. More than « using research »: the real challenges in promoting evidence-informed decision-making. Healthc Policy Polit. 2009;4(3):87–102.

Peirson L, Ciliska D, Dobbins M, Mowat D. Building capacity for evidence informed decision making in public health: a case study of organizational change. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:137.

Barwick MA, Peters J, Boydell K. Getting to uptake: do communities of practice support the implementation of evidence-based practice? J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;18(1):16–29.

Tchameni Ngamo S, Souffez K, Lord C, Dagenais C. Do knowledge translation (KT) plans help to structure KT practices? Health Res Policy Syst. 2016;14(1):46.

Lemire N, Laurendeau M-C, Souffez K, Institut national de santé publique du Québec, Direction recherche formation et développement. Animer un processus de transfert des connaissances: bilan des connaissances et outil d’animation. Montréal: Direction de la recherche, formation et développement, Institut national de santé publique Québec; 2009. https://www.deslibris.ca/ID/222221. Accessed 12 Jan 2020.

Slaughter SE, Zimmermann GL, Nuspl M, Hanson HM, Albrecht L, Esmail R, et al. Classification schemes for knowledge translation interventions: a practical resource for researchers. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2017;17:161.

Lavis J, Lomas J, Hamid M, Sewankambo N. Assessing country-level efforts to link research to action. Bull World Health Organ. 2006;84(8):620–8.

Linsley P, Howard D, Owen S. The construction of context-mechanisms-outcomes in realistic evaluation. Nurse Res. 2015;22(3):28–34.

Wong G, Westhorp G, Greenhalgh J, Manzano A, Jagosh J, Greenhalgh T. Quality and reporting standards, resources, training materials and information for realist evaluation: the RAMESES II project. Southampton: NIHR Journals Library; 2017. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459059/. Accessed 28 May 2019.

Salter KL, Kothari A. Using realist evaluation to open the black box of knowledge translation: a state-of-the-art review. Implement Sci. 2014;9:115.

Michie S, Hyder N, Walia A, West R. Development of a taxonomy of behaviour change techniques used in individual behavioural support for smoking cessation. Addict Behav. 2011;36:315–9.

Acknowledgements

The authors are very grateful to all those who took part in the project, especially the members of the regional support teams and the Fédération Nationale d’Education pour la Santé.

Funding

The research received funding from a recognised national research agency, the IReSP (Institut de Recherche en Santé Publique/Research Institute in Public Health). The funding was obtained through a national competitive peer review grant application process, called “2016 General call for projects–Prevention” (No., CAMBON-AAP16-PREV-11).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All the authors contributed to the study concept and design. The material preparation, data collection and analyses were performed by Aurélie Affret, Ollivier Prigent, Marion Porcherie, Olivier Aromatario and Linda Cambon. The study was supervised by Linda Cambon. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Aurélie Affret and Linda Cambon and all the authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All of the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The project was carried out in full compliance with current legislation (e.g. the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the EU) and international conventions (e.g. the Helsinki Declaration). The method design, data collection and analysis took the following issues into consideration: anonymity of study respondents was preserved and ensured at all times at the request of respondent(s). Unnecessary collection of personal data was avoided and respondents had the right to review the output and withdraw consent. All personal data were coded, removed from the data for analysis and stored separately. Only designated research staff had access to the keys linking the data with the personal information. Informed consent was obtained from all the study participants and, in the case of refusal, alternative means of data collection were explored (e.g. alternative respondents). In addition, the study received approval from the national agency for data protection, the Commission Nationale Informatique et Libertés (NS no. 43, registered number: 2028640 v 0).

Consent for publication

Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in the study.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Affret, A., Prigent, O., Porcherie, M. et al. Development of a knowledge translation taxonomy in the field of health prevention: a participative study between researchers, decision-makers and field professionals. Health Res Policy Sys 18, 91 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-020-00602-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-020-00602-z