Abstract

Background

Platelet inhibition is important for patients with coronary artery disease. When dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) is required, a P2Y12-antagonist is usually recommended in addition to standard aspirin therapy. The most used P2Y12-antagonists are clopidogrel, prasugrel and ticagrelor. Despite DAPT, some patients experience adverse cardiovascular events, and insufficient platelet inhibition has been suggested as a possible cause. In the present review we have performed a literature search on prevalence, mechanisms and clinical implications of resistance to P2Y12 inhibitors.

Methods

The PubMed database was searched for relevant papers and 11 meta-analyses were included. P2Y12 resistance is measured by stimulating platelets with ADP ex vivo and the most used assays are vasodilator stimulated phosphoprotein (VASP), Multiplate, VerifyNow (VN) and light transmission aggregometry (LTA).

Discussion/conclusion

The frequency of high platelet reactivity (HPR) during clopidogrel therapy is predicted to be 30%. Genetic polymorphisms and drug-drug interactions are discussed to explain a significant part of this inter-individual variation. HPR during prasugrel and ticagrelor treatment is estimated to be 3–15% and 0–3%, respectively. This lower frequency is explained by less complicated and more efficient generation of the active metabolite compared to clopidogrel. Meta-analyses do show a positive effect of adjusting standard clopidogrel treatment based on platelet function testing. Despite this, personalized therapy is not recommended because no large-scale RCT have shown any clinical benefit. For patients on prasugrel and ticagrelor, platelet function testing is not recommended due to low occurrence of HPR.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Platelet inhibition is pivotal to reduce cardiovascular events (CVE) in patients with coronary artery disease (CAD). The cornerstone in such treatment is aspirin, but when dual antiplatelet treatment (DAPT) is required, adding a P2Y12 inhibitor is usually recommended. The most used P2Y12 inhibitors are clopidogrel, prasugrel and ticagrelor. Their different properties are shown in Fig. 1 and Table 1.

The role of the P2Y12 receptors in ADP stimulated platelet activation. Adapted from [1]

Clopidogrel has been the most used P2Y12 inhibitor in routine clinical practice for years and has been the subject of a considerable amount of research. DAPT with aspirin and clopidogrel was previously the preferred combination, but this changed after prasugrel and ticagrelor were introduced. Prasugrel has replaced clopidogrel in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), and ticagrelor is preferred in patients with non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) after PCI [2, 4]. Prasugrel and ticagrelor reduce new cardiovascular events more efficiently in these patient populations, but on the other hand more bleeding complications are reported [5, 6]. After elective PCI in patients with stable CAD, clopidogrel is still the first choice [7].

Despite DAPT, some patients still experience recurrent cardiovascular events. This may be due to many reasons, but insufficient platelet inhibition has been suggested a possible cause, and inter-individual differences in response are well known. A challenge in antiplatelet therapy is the lack of a standardized way to titrate the drug dose to achieve sufficient platelet inhibition and personalize treatment, like we can do with lipid-lowering and blood pressure medication [8].

Lack of response to antiplatelet therapy, termed resistance, non-responsiveness or high platelet reactivity (HPR) despite use of platelet inhibitors, has been widely studied. It has been distinguished between clinical and laboratory non-responsiveness. Clinical non-responsiveness is discussed when platelet-inhibited patients experience cardiovascular events. Laboratory non-responsiveness is defined when platelets still are active ex vivo despite treatment. These phenomena have only to some degree been shown to overlap [8].

Also, non-compliance i.e. patients not taken their medication, has to be considered when discussing the responsiveness/resistance phenomenon in clinical practice. This is, however, not discussed in the present review.

Studies on platelet non-responsiveness were initially focused on aspirin which has been extensively studied. When clopidogrel was introduced, this phenomenon was early addressed, and has later been studied also with regard to other P2Y12 inhibitors. The interindividual response variability to clopidogrel is well established [9, 10]. Response variability to ticagrelor and prasugrel, on the other hand, is less known.

The aim of the present work was to summarize the literature on prevalence, mechanisms and clinical implications of resistance to P2Y12 receptor inhibitors and give a conclusion based on the reports available.

Methods

ESC Guidelines on “Ischaemic Heart Disease and Acute Cardiac Care” [2, 11, 12] were used to discuss clinical guidelines for the different states of coronary artery disease.

Search strategy

Studies until the 11th of December 2017 were included in the literature search. The PubMed database was used. Phrases or synonyms for “P2Y12 receptor antagonists” and “drug resistance” (shown below), were used identifying 1228 papers. When limiting the search to English language and last 5 years, in which the novel P2Y12 inhibitors have been incorporated into clinical practice, the number of papers was reduced to 540.

Our search strategy was as following:

(“Purinergic P2Y Receptor Antagonists” [mesh] OR ((ADP[Title] OR P2Y12[Title]) AND (Antagonist*[Title] OR blocker*[Title])) OR clopidogrel[Title] OR prasugrel[Title] OR ticagrelor[title]) AND (“Drug Resistance”[Mesh] OR “Pharmacogenetics”[Mesh] OR resistance[Title] OR respons*[Title] OR respond*[Title] OR toleran*[Title] OR nonrespon*[Title] OR reactiv*[Title]) AND “last 5 years”[PDat] AND English[lang]

Further focus on systematic reviews by adding “systematic[sb]” to the search strategy, identified 26 papers. To discover any potential Cochrane reviews, we added “Cochrane Database Syst Rev”[Journal] to the search, but 0 papers were found.

Of the 26 systematic reviews, we excluded 8 due to lack of power, studying non-CAD population or not being meta-analyses.

Results on genetic aspects (7 papers) were excluded from this review due to the complexity without obvious relevance for functionality, other than one specific single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs)‘s influence on clopidogrel function. The topic is to some degree featured in the discussion. Thus, 11 meta-analyses are included.

Methods to determine P2Y12 resistance/non-responsiveness

P2Y12resistance is measured by stimulating platelets with ADP ex vivo. There are different assays for this purpose and the most used are measure of vasodilator stimulated phosphoprotein (VASP), Multiplate, VerifyNow (VN) and light transmission aggregometry (LTA). Platelet aggregometry induced by ADP is a functional test with a more global aggregation measure than e.g. VASP, which is more specific to drug action at subcellular levels. Aggregometry is the basic principle for VerifyNow, Multiplate and LTA.

Determination of drug response by all these methods have shown to predict clinical outcome in a significant number of patients after PCI [13]. Nevertheless, the expert consensus guidelines do not recommend LTA unless none of the other assays are available. This is due to lack of standardization of this method [13]. The currently recommended assays are therefore the VerifyNow, the Multiplate assay and the VASP assay. However, in clinical practice VerifyNow and Multiplate are preferred due to their standardized and user-friendly set up.

Another issue is determination of cut-off values for the definition of “laboratory non-responsiveness”. The optimal threshold is still being investigated and may vary depending on the clinical situation. The current recommendation is 208 PRU with VerifyNow, 46 AU with the Multiplate assay and 50% with the VASP assay [13].

Discussion

Meta-analyses on laboratory non-responsiveness to P2Y12 antagonism

The number of patients included in the analyses investigating laboratory non-responsiveness range from 445 to 5395. This variation may be explained by different inclusion criteria, the number of drugs included and the type and number of laboratory methods used. A summary of the meta-analyses on laboratory non-responsiveness are shown in Table 2.

Meta-analyses on clinical outcome of non-responsiveness to P2Y12 antagonism

In the analyses investigating clinical outcome the number of patients varies from 605 to 28,178. This wide range may also be explained by different inclusion criteria, the number of drugs included, different study design and follow-up time, in addition to the laboratory methods used. A summary of the meta-analyses on clinical outcome are shown in Table 3.

Prevalence and mechanisms of high platelet reactivity (HPR) in P2Y12-antagonists

Clopidogrel

The prevalence of high platelet reactivity (HPR) during clopidogrel treatment is high. However, the estimates have been inconsistent and dependent on the laboratory methods and cut off values used. From the expert consensus guidelines from 2014, the prevalence is predicted to be approximately 30% [13], which also fits with the meta-analysis by D’Ascenzo, F. et al. (Table 3).

Which factors that cause this huge variation in clopidogrel response is not fully resolved, but the most important factors seem to be genetic polymorphisms and drug-drug interactions [25].

Hepatic activation of clopidogrel and conversion into an active metabolite is essential for the inhibition of the P2Y12 receptor [26, 27]. This metabolization is dependent of the cytochrome P450 isoenzymes (CYPs) [28]. The isoenzymes CYP2C19 is shown to be of particular interest and is said to explain 12–15% of the variable response to clopidogrel [10]. About 25 SNPs coding for CYP2C19 have been described in which CYP2C19*2 seems to be of most importance, i.e. shown to reduce serum concentration of the active metabolite and also to reduce inhibition of platelet aggregation [29, 30]. Reduced function of CYP2C19 has been reported to increase the risk for MACE [31, 32].

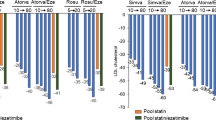

Drug interactions can also affect clopidogrel response. Rifampicin induces several CYPs, including CYP2C19, and leads to higher levels of active clopidogrel with subsequent greater P2Y12 receptor blockade [33]. Ketoconazole on the other hand inhibits CYP3A4 and leads to reduced clopidogrel activation [34]. Proton pump inhibitors (PPI) depend on CYP2C19 metabolism like clopidogrel. Chen et al. have reported that combining these drugs increase the risk of clopidogrel resistance, but may be clinically unimportant, as no significant difference in major adverse cardiac events were observed [24]. Treatment with statins which are metabolized by CYP3A4 has shown not or only slightly to reduce platelet reactivity, but not to affect clinical outcome [35, 36].

Other factors that are discussed to contribute to low clopidogrel response are poor absorption, P2Y12 receptor polymorphisms, increased platelet turnover, different clinical factors like sex, diabetes, kidney disease, obesity, hypercholesterolemia [23, 25, 37].

Prasugrel and ticagrelor

There is broad scientific consensus that patients on prasugrel or ticagrelor are less susceptible to HPR than patients on clopidogrel, as also shown from the results in Table 2. Like the estimates for clopidogrel resistance, there has also been discrepancy between the reported prevalence of resistance to both prasugrel and ticagrelor.

The variation in the reported prevalence’s may partly be due to lack of methodological standardization. Difference in the HPR definition across the studies is one limitation [16], but it also seems like PR varies depending on loading sequence, pre-treatment with clopidogrel, time point of testing, switching strategy, and patient population included [38].

Lemesle et al. have published a meta-analysis (Table 2) and included studies looking at the rate of HPR in the acute phase during loading dose (LD), but also during maintenance dose (MD) [16]. When isolating studies that tested PR after loading dose, no significant differences between the ticagrelor and prasugrel group were found. Nevertheless, when testing the impact of the maintenance dose, the rate of HPR was significantly lower in the ticagrelor group. The overall rate of HPR was significantly lower in the ticagrelor vs. prasugrel group [15]. Also the meta-analysis by Zhang et al. describe PR to be similar between the ticagrelor and prasugrel group after loading dose, but lower in the ticagrelor group during maintenance dose [14]. The meta-analysis by Lhermusier et al., though only including studies during maintenance dose, supports this observation [15].

The rate of HPR on prasugrel and ticagrelor treatment has not been established, but it is on maintenance dose estimated to be 3–15% for patients on prasugrel and 0–3% for ticagrelor treated patients [25]. Despite the low PR for both drugs, comparisons have shown that ticagrelor is the most potent platelet inhibitor and has the lowest prevalence of HPR [15, 16, 25].

The differences in HPR between clopidogrel, prasugrel and ticagrelor can partly be explained by the differences in their pharmacokinetics. Prasugrel has more efficient generation of active metabolite compared to clopidogrel [39, 40]. It is less dependent of CYP2C19 metabolism, and therefore not as affected by genetic variants of this enzyme [41, 42]. The most potent agent, ticagrelor, is an active drug and is not dependent on enzyme activation, i.e. is less susceptible to drug-drug interactions or pharmacogenetic influences [43]. Nevertheless, it has been shown that levels of active ticagrelor are affected by genetic variants of SLCO1B1 (solute carrier organic anion transporter family member 1B1) and UGT2B7 (UDP glucuronosyltransferase family 2 member B7). These gene variants have, however, not been shown to have any clinical implication [41]. PR on ticagrelor was affected by age, BMI and smoking status i.e. patients with increasing age and BMI have higher PR, and smokers lower PR [17]. Nevertheless, the PR on ticagrelor was generally very low and the rate of non-responders was 0% in this meta-analysis.

HPR as a predictor of clinical outcome and personalized antiplatelet therapy

Multiple studies have shown that patients with HPR during clopidogrel treatment are at greater risk for MACE [10]. Because of this, individualization of antiplatelet therapy based on platelet function testing has been studied in several RCTs. The principle in these trials has mainly been to compare the effect of intensified antiplatelet therapy (IAT) against conventional antiplatelet therapy (CAT) on clinical outcome in patients with HPR. The IAT protocols differ in the studies and is either increasing the clopidogrel dose or changing to prasugrel or ticagrelor. The results from these studies are diverging.

A meta-analysis performed by Zhou et al. (Table 3) found that patients undergoing PCI treated with IAT based on platelet function testing had reduced risk of MACE, CV death, stent thrombosis and target vessel revascularization, without any increase in the risk of bleeding [18]. Xu et al. found similar results in their meta-analysis with significantly reduced risk of CV death, nonfatal MI and stent thrombosis in the IAT group [19]. Ma et al. also found that patients with HPR did benefit from IAT compared to conventional antiplatelet therapy (CAT), where the observed benefits were mainly attributed to treatment-associated reduction in stent thrombosis and target vessel revascularization [21]. Even though these meta-analyses reach the same conclusion, they are similar and with some exceptions based on the same studies.

Despite similar results from these three meta-analysis, no large-scale randomized clinical trial has demonstrated any benefit of personalized antiplatelet therapy [37]. The GRAVITAS trial found no difference in clinical endpoints when comparing high dose vs. low dose clopidogrel among patients with HPR undergoing PCI. The number of clinical endpoints in this study was, however, very low, and less than half of the estimated number in the power calculations (5%). In addition, the platelet function testing was undertaken 12–24 h after the PCI, which may be have been too late to affect the outcome [44]. The TRIGGER-PCI study found that switching from clopidogrel to prasugrel in patients with HPR lead to a reduction in platelet reactivity, but no improvement in clinical outcome were observed. However, the trial was stopped prematurely after 6 months due to a lower endpoint rate than expected, and the study did therefore not achieve the desired power. And also in this study, platelet function testing with subsequent adjustment was not done before the morning after PCI [45]. The ARCTIC trial randomly assigned patients to a strategy with platelet function monitoring and treatment adjustment in non-responders, or to standard therapy without monitoring. Of the patients with HPR, about 80% received an increased clopidogrel dose, while only approximately 3% were started on prasugrel. The study showed no significant improvement in clinical endpoints with platelet function testing and subsequent drug adjustment as compared with the conventional strategy [46]. The ANTARCTIC trial randomized patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) above 75 years to prasugrel with or without platelet function monitoring with drug adjustment when indicated. They observed no differences in clinical outcome between the two groups [47].

In the meta-analysis by Reny et al. it was reported that the association between the risk of MACE and HPR significantly increases with the number of risk factors [20]. They suggest that the association between MACE and PR is dependent of the patient’s cardiovascular profile. The risk factors that are thought to increase the risk of PR and MACE are among others age > 75, ACS at inclusion, diabetes and hypertension. This is supported by another meta-analysis where HPR did not increase the risk of adverse events after adjusting for risk factors [23]. Lack of multivariate analysis may have confounded the evaluation of the independent risk of HPR and may be the reason why all RCTs have failed when trying to show a beneficial effect of individualized antiplatelet therapy based on platelet function testing. The conflicting results between the meta-analyses and the large RCTs may also be due to publication bias.

Antiplatelet therapy and platelet function testing in clinical practice

The current guidelines for DAPT is to combine aspirin with a P2Y12 blocker. Which P2Y12 blocker depends on the clinical situation. For stable CAD patients after elective PCI, DAPT with clopidogrel is recommended, but for patients presenting with ACS prasugrel or ticagrelor are preferred [12].

The ESC guidelines do not recommend platelet function testing in routine clinical practice before or after elective stenting [12]. This is because no large-scale RCT has demonstrated any beneficial effect of adjusting therapy based on platelet function testing during clopidogrel treatment. With regards to prasugrel and ticagrelor, tailored therapy based on platelet function has not been that widely investigated, as HPR on these drugs is rare. Thus, platelet function testing is not recommended in these patients either [13].

The “ACCF/AHA/SCAI Guideline for PCI” also states that platelet function testing should not be used in routine clinical practice. Nevertheless, they say that testing may be considered in patients at high risk for MACE and that alternative agents such as prasugrel and ticagrelor might be considered in clopidogrel-treated patients with HPR [48]. However, these guidelines are from 2011 and are not based on the results from more recent RCTs.

Conclusion

The prevalence of HPR is greater in patients treated with clopidogrel (approximately 30%) compared to patients on the more novel antiplatelet agents prasugrel (3–15%) and ticagrelor (0–3%). These differences are likely due to different drug pharmacokinetics where prasugrel and ticagrelor have more efficient generation of active metabolite compared to clopidogrel.

Although meta-analyses show an effect of adjusting standard clopidogrel treatment based on platelet function testing, personalized therapy is not recommended because no large-scale RCT have shown any clinical benefit. Nevertheless, it should be noticed that the performed RCTs were underpowered to show any clinical effect. Personalized therapy is neither recommended for patients on prasugrel nor ticagrelor due to low occurrence of HPR on these respective drugs.

Abbreviations

- ACS:

-

acute coronary syndrome

- AU:

-

aggregation units

- BMI:

-

body mass index

- CAD:

-

coronary artery disease

- CAT:

-

conventional antiplatelet therapy

- CV:

-

cardiovascular

- CVE:

-

cardiovascular events

- CYPs:

-

cytochrome P450 isoenzymes

- DAPT:

-

dual antiplatelet therapy

- ESC:

-

European Society of Cardiology

- HPR:

-

high platelet reactivity

- IAT:

-

intensified antiplatelet therapy

- LD:

-

loading dose

- LPR:

-

low platelet reactivity

- LTA:

-

light transmission aggregometry

- MACCE:

-

major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events

- MACE:

-

major adverse cardiovascular events

- MD:

-

maintenance dose

- MI:

-

myocardial infarction

- MPA:

-

maximal platelet aggregation

- NSTEMI:

-

non-ST elevation myocardial infarction

- OR:

-

odds ratio

- PCI:

-

percutaneous coronary intervention

- PPI:

-

protein pump inhibitors

- PR:

-

platelet reactivity

- PRI:

-

platelet reactivity index

- PRU:

-

platelet reactivity units

- RCTs:

-

randomized controlled trials

- RR:

-

relative risk

- SD:

-

standard dose

- ST:

-

stent thrombosis

- STEMI:

-

ST-elevation myocardial infarction

- TEG:

-

thrombelastography

- TVR:

-

target vessel revascularization

- VASP:

-

Vasodilator stimulated phosphoprotein

- VN:

-

VerifyNow-P2Y12

- WMD:

-

weighted mean difference

References

Angiolillo DJ, Ueno M. Optimizing platelet inhibition in clopidogrel poor metabolizers: therapeutic options and practical considerations. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;4(4):411–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcin.2011.03.001.

Roffi M, Patrono C, Collet J-P, Mueller C, Valgimigli M, Andreotti F, et al. 2015 ESC guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevationTask force for the Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2016;37(3):267–315. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehv320.

Angiolillo DJ, Rollini F, Storey RF, Bhatt DL, James S, Schneider DJ, et al. International expert consensus on switching platelet P2Y12 receptor-inhibiting therapies. Circulation. 2017;136(20):1955–75. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.117.031164.

Steg PG, James SK, Atar D, Badano LP, Blomstrom-Lundqvist C, Borger MA, et al. ESC guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. 2012;33(20):2569–619. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehs215.

Wiviott SD, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, Montalescot G, Ruzyllo W, Gottlieb S, et al. Prasugrel versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(20):2001–15. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0706482.

Wallentin L, Becker RC, Budaj A, Cannon CP, Emanuelsson H, Held C, et al. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(11):1045–57. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0904327.

Montalescot G, Sechtem U, Achenbach S, Andreotti F, Arden C, Budaj A, et al. 2013 ESC guidelines on the management of stable coronary artery disease: the task force on the management of stable coronary artery disease of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2013;34(38):2949–3003. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/eht296.

Kuliczkowski W, Witkowski A, Polonski L, Watala C, Filipiak K, Budaj A, et al. Interindividual variability in the response to oral antiplatelet drugs: a position paper of the working group on antiplatelet drugs resistance appointed by the section of cardiovascular interventions of the polish cardiac society, endorsed by the working group on thrombosis of the European society of cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2009;30(4):426–35. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehn562.

Parodi G, Marcucci R, Valenti R, Gori AM, Migliorini A, Giusti B, et al. High residual platelet reactivity after clopidogrel loading and long-term cardiovascular events among patients with acute coronary syndromes undergoing PCI. JAMA. 2011;306(11):1215–23. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2011.1332.

Oliphant CS, Trevarrow BJ, Dobesh PP. Clopidogrel response variability: review of the literature and practical considerations. J Pharm Pract. 2016;29(1):26–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/0897190015615900.

Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, Antunes MJ, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, Bueno H, et al. 2017 ESC guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevationThe task force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2018;39(2):119–77. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehx393.

Valgimigli M, Bueno H, Byrne RA, Collet J-P, Costa F, Jeppsson A, et al. 2017 ESC focused update on dual antiplatelet therapy in coronary artery disease developed in collaboration with EACTSThe task force for dual antiplatelet therapy in coronary artery disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and of the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J. 2018;39(3):213–60. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehx419.

Aradi D, Storey RF, Komocsi A, Trenk D, Gulba D, Kiss RG, et al. Expert position paper on the role of platelet function testing in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Eur Heart J. 2014;35(4):209–15. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/eht375.

Zhang H, Zhang P, Dong P, Yang X, Wang Y, Zhang H, et al. Effect of ticagrelor versus prasugrel on platelet reactivity: a meta-analysis. Coron Artery Dis. 2017;28(7):597–604. https://doi.org/10.1097/mca.0000000000000541.

Lhermusier T, Lipinski MJ, Tantry US, Escarcega RO, Baker N, Bliden KP, et al. Meta-analysis of direct and indirect comparison of ticagrelor and prasugrel effects on platelet reactivity. Am J Cardiol. 2015;115(6):716–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.12.029.

Lemesle G, Schurtz G, Bauters C, Hamon M. High on-treatment platelet reactivity with ticagrelor versus prasugrel: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thromb Haemost. 2015;13(6):931–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/jth.12907.

Alexopoulos D, Xanthopoulou I, Storey RF, Bliden KP, Tantry US, Angiolillo DJ, et al. Platelet reactivity during ticagrelor maintenance therapy: a patient-level data meta-analysis. Am Heart J. 2014;168(4):530–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2014.06.026.

Zhou Y, Wang Y, Wu Y, Huang C, Yan H, Zhu W, et al. Individualized dual antiplatelet therapy based on platelet function testing in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2017;17(1):157. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-017-0582-6.

Xu L, Hu XW, Zhang SH, Li JM, Zhu H, Xu K, et al. Intensified antiplatelet treatment reduces major cardiac events in patients with Clopidogrel low response: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Chin Med J. 2016;129(8):984–91. https://doi.org/10.4103/0366-6999.179786.

Reny JL, Fontana P, Hochholzer W, Neumann FJ, Ten Berg J, Janssen PW, et al. Vascular risk levels affect the predictive value of platelet reactivity for the occurrence of MACE in patients on clopidogrel. Systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data. Thromb Haemost. 2016;115(4):844–55. https://doi.org/10.1160/th15-09-0742.

Ma W, Liang Y, Zhu J, Wang Y, Wang X. Meta-analysis appraising high maintenance dose clopidogrel in patients who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention with and without high on-clopidogrel platelet reactivity. Am J Cardiol. 2015;115(5):592–601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.12.013.

Lin L, Wang H, Chen YF, Lin WW, Wang CL, Lin CH. High maintenance dose of clopidogrel in patients with high on-treatment platelet reactivity after a percutaneous coronary intervention: a meta-analysis. Coron Artery Dis. 2015;26(5):386–95. https://doi.org/10.1097/mca.0000000000000246.

D'Ascenzo F, Barbero U, Bisi M, Moretti C, Omede P, Cerrato E, et al. The prognostic impact of high on-treatment platelet reactivity with aspirin or ADP receptor antagonists: systematic review and meta-analysis. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:610296. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/610296.

Chen J, Chen SY, Lian JJ, Zeng XQ, Luo TC. Pharmacodynamic impacts of proton pump inhibitors on the efficacy of clopidogrel in vivo--a systematic review. Clin Cardiol. 2013;36(4):184–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/clc.22094.

Thomas MR, Storey RF. Clinical significance of residual platelet reactivity in patients treated with platelet P2Y12 inhibitors. Vasc Pharmacol. 2016;84:25–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vph.2016.05.010.

Zhang Y, Zhang S, Ding Z. Role of P2Y12 receptor in thrombosis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;906:307–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/5584_2016_123.

Thomas MR, Storey RF. Optimal management of antiplatelet therapy and proton pump inhibition following percutaneous coronary intervention. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med. 2012;14(1):24–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11936-011-0157-2.

Siller-Matula JM, Trenk D, Schror K, Gawaz M, Kristensen SD, Storey RF, et al. Response variability to P2Y12 receptor inhibitors: expectations and reality. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;6(11):1111–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcin.2013.06.011.

Mao L, Jian C, Changzhi L, Dan H, Suihua H, Wenyi T, et al. Cytochrome CYP2C19 polymorphism and risk of adverse clinical events in clopidogrel-treated patients: a meta-analysis based on 23,035 subjects. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2013;106(10):517–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acvd.2013.06.055.

Pettersen AA, Arnesen H, Opstad TB, Seljeflot I. The influence of CYP 2C19*2 polymorphism on platelet function testing during single antiplatelet treatment with clopidogrel. Thromb J. 2011;9:4. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-9560-9-4.

Mega JL, Close SL, Wiviott SD, Shen L, Hockett RD, Brandt JT, et al. Cytochrome p-450 polymorphisms and response to clopidogrel. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(4):354–62. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0809171.

Simon T, Verstuyft C, Mary-Krause M, Quteineh L, Drouet E, Meneveau N, et al. Genetic determinants of response to clopidogrel and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(4):363–75. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0808227.

Judge HM, Patil SB, Buckland RJ, Jakubowski JA, Storey RF. Potentiation of clopidogrel active metabolite formation by rifampicin leads to greater P2Y12 receptor blockade and inhibition of platelet aggregation after clopidogrel. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8(8):1820–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.03925.x.

Farid NA, Payne CD, Small DS, Winters KJ, Ernest CS 2nd, Brandt JT, et al. Cytochrome P450 3A inhibition by ketoconazole affects prasugrel and clopidogrel pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics differently. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2007;81(5):735–41. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.clpt.6100139.

Park JS, Cha KS, Lee HW, Oh JH, Choi JH, Lee HC, et al. Platelet reactivity and clinical outcomes in patients using CYP3A4-metabolized statins with clopidogrel in percutaneous coronary intervention. Heart Vessel. 2017;32(6):690–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00380-016-0927-6.

Trenk D, Hochholzer W, Frundi D, Stratz C, Valina CM, Bestehorn HP, et al. Impact of cytochrome P450 3A4-metabolized statins on the antiplatelet effect of a 600-mg loading dose clopidogrel and on clinical outcome in patients undergoing elective coronary stent placement. Thromb Haemost. 2008;99(1):174–81. https://doi.org/10.1160/th07-08-0503.

Franchi F, Angiolillo DJ. Novel antiplatelet agents in acute coronary syndrome. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2015;12(1):30–47. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrcardio.2014.156.

Siller-Matula JM, Hintermeier A, Kastner J, Kreiner G, Maurer G, Kratochwil C, et al. Distribution of clinical events across platelet aggregation values in all-comers treated with prasugrel and ticagrelor. Vasc Pharmacol. 2016;79:6–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vph.2016.01.003.

Wiviott SD, Trenk D, Frelinger AL, O'Donoghue M, Neumann FJ, Michelson AD, et al. Prasugrel compared with high loading- and maintenance-dose clopidogrel in patients with planned percutaneous coronary intervention: the Prasugrel in comparison to Clopidogrel for inhibition of platelet activation and aggregation-thrombolysis in myocardial infarction 44 trial. Circulation. 2007;116(25):2923–32. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.107.740324.

Wallentin L, Varenhorst C, James S, Erlinge D, Braun OO, Jakubowski JA, et al. Prasugrel achieves greater and faster P2Y12receptor-mediated platelet inhibition than clopidogrel due to more efficient generation of its active metabolite in aspirin-treated patients with coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J. 2008;29(1):21–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehm545.

Friede K, Li J, Voora D. Use of Pharmacogenetic information in the treatment of cardiovascular disease. Clin Chem. 2017;63(1):177–85. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2016.255232.

Mega JL, Close SL, Wiviott SD, Shen L, Hockett RD, Brandt JT, et al. Cytochrome P450 genetic polymorphisms and the response to prasugrel: relationship to pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic, and clinical outcomes. Circulation. 2009;119(19):2553–60. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.109.851949.

Birkeland K, Parra D, Rosenstein R. Antiplatelet therapy in acute coronary syndromes: focus on ticagrelor. J Blood Med. 2010;1:197–219. https://doi.org/10.2147/jbm.s9650.

Price MJ, Berger PB, Teirstein PS, Tanguay JF, Angiolillo DJ, Spriggs D, et al. Standard- vs high-dose clopidogrel based on platelet function testing after percutaneous coronary intervention: the GRAVITAS randomized trial. JAMA. 2011;305(11):1097–105. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2011.290.

Trenk D, Stone GW, Gawaz M, Kastrati A, Angiolillo DJ, Muller U, et al. A randomized trial of prasugrel versus clopidogrel in patients with high platelet reactivity on clopidogrel after elective percutaneous coronary intervention with implantation of drug-eluting stents: results of the TRIGGER-PCI (testing platelet reactivity in patients undergoing elective stent placement on Clopidogrel to guide alternative therapy with Prasugrel) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59(24):2159–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2012.02.026.

Collet JP, Cuisset T, Range G, Cayla G, Elhadad S, Pouillot C, et al. Bedside monitoring to adjust antiplatelet therapy for coronary stenting. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(22):2100–9. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1209979.

Cayla G, Cuisset T, Silvain J, Leclercq F, Manzo-Silberman S, Saint-Etienne C, et al. Platelet function monitoring to adjust antiplatelet therapy in elderly patients stented for an acute coronary syndrome (ANTARCTIC): an open-label, blinded-endpoint, randomised controlled superiority trial. Lancet. 2016;388(10055):2015–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31323-x.

Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, Bailey SR, Bittl JA, Cercek B, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI guideline for percutaneous coronary intervention: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. Circulation. 2011;124(23):e574–651. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0b013e31823ba622.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank librarian Maria S. Isachsen for excellent assistance with the literature search.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EW performed the literature search, contributed to interpretation of results and drafted the manuscript. IS and HA contributed with the interpretation of the results and the intellectual content of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Warlo, E.M.K., Arnesen, H. & Seljeflot, I. A brief review on resistance to P2Y12 receptor antagonism in coronary artery disease. Thrombosis J 17, 11 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12959-019-0197-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12959-019-0197-5