Abstract

Background

The pathophysiological mechanisms of acute coagulopathy of trauma-shock (ACOTS) are reported to include activated protein C-mediated suppression of thrombin generation via the proteolytic inactivation of activated Factor V (FVa) and FVIIIa; an increased fibrinolysis via neutralization of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) by activated protein C. The aims of this study are to review the evidences for the role of activated protein C in thrombin generation and fibrinolysis and to validate the diagnosis of ACOTS based on the activated protein C dynamics.

Methods

We conducted systematic literature search (2007–2017) using PubMed, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL). Clinical studies on trauma that measured activated protein C or the circulating levels of activated protein C-related coagulation and fibrinolysis markers were included in our study.

Results

Out of 7613 studies, 17 clinical studies met the inclusion criteria. The levels of activated protein C in ACOTS were inconsistently decreased, showed no change, or were increased in comparison to the control groups. Irrespective of the activated protein C levels, thrombin generation was always preserved or highly elevated. There was no report on the activated protein C-mediated neutralization of PAI-1 with increased fibrinolysis. No included studies used unified diagnostic criteria to diagnose ACOTS and those studies also used different terms to refer to the condition known as ACOTS.

Conclusions

None of the studies showed direct cause and effect relationships between activated protein C and the suppression of coagulation and increased fibrinolysis. No definitive diagnostic criteria or unified terminology have been established for ACOTS based on the activated protein C dynamics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Coagulation and fibrinolysis are innate immune responses; they develop nonspecifically start following infectious and noninfectious insults, such as sepsis and trauma [1]. These responses occur at the site of the insult to limit host damage and they have roles in the compartmentalization of danger- and pathogen-associated molecular patterns, which suppress dissemination of these patterns into the circulation [1,2,3]. These processes are referred to as hemostasis and wound healing in trauma. During normal hemostasis, anticoagulant pathways, tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI), antithrombin, protein C, and thrombomodulin restrict clot dissemination at intact sites. Protein C and thrombomodulin have important roles in controlling coagulation, fibrinolysis and inflammation via activated protein C, thrombin-activatable fibrinolysis inhibitor (TAFI) and endothelial protein C receptor (EPCR) [4, 5]. These physiological systems cannot work in severely injured trauma patients, which is associated with endothelial injury; thus, sever trauma leads to systemic thrombin generation, a condition that is called disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) [6].

In 2007, a condition called “acute coagulopathy of trauma-shock” (ACOTS) was newly proposed [7,8,9]. Another paper [10] and a review approved this hypothesis [11], and thereafter ACOTS was established as major pathophysiological concept in trauma-induced coagulopathy [12]. The pathogenesis of ACOTS is summarized as follows, based on several review articles [7, 11, 13,14,15,16,17]. ACOTS, in which activated protein C plays central roles, only occurs at the very early period after injury in only patients with shock and severe acidosis. Traumatic shock slows the clearance of thrombin, increasing its binding to newly expressed thrombomodulin on the normal endothelium and soluble thrombomodulin with full domains and a 100% activity in the circulation. Thrombin and thrombomodulin complexes induce the systemic production of activated protein C, which inactivates activated Factors V (FVa) and VIII (FVIIIa) and neutralizes plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1). This is followed by suppression of thrombin generation and an increase in the production of tissue-type plasminogen activator (t-PA). In addition, the fibrinogen levels always remain normal, indicating that less thrombin is available to cleave fibrinogen.

However, a number of researchers have expressed doubts in this theory. One group noted that the immediate massive generation of thrombin and it activation in the systemic circulation, insufficient anticoagulant pathways associated with endothelial injury and suggested that this is the main pathophysiological mechanisms of trauma-induced coagulopathy, which coincides with the definition of DIC reported by the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH) [18,19,20,21,22,23]. In addition to secondary fibrinolysis due to DIC, the accelerated release of t-PA from the injured endothelium due to traumatic shock-induced hypoperfusion, the consumption of α2-antiplasmins, and increased levels of neutrophil elastase synergistically mediate systemic fibrin (nogen) olysis. The time delay between the immediate release of t-PA from the endothelium and the expression of PAI-1 mRNA enhances fibrin (ogen) olysis immediately after injury. In addition, the massive generation of tissue factors cause fibrin (ogen) olysis. These conditions, the coexistence of DIC and pathological systemic fibrin (ogen) olysis are referred to as DIC with the fibrinolytic phenotype [24].

Another group also expressed doubts regarding the theory that ACOTS is driven by activated protein C [25,26,27,28]. They acknowledged that the currently available evidence suggests that ACOTS occurs due to the massive stimulation of thrombin generation, platelet and fibrinogen consumption, and fibrinolysis by damaged tissues, and they suggested that these data indicate a consumptive coagulopathy. Furthermore, the levels of activated protein C observed in ACOTS are far from the concentration that can cleave both platelet and plasma FVa. In plasma, PAI-1 is completely bound to vitronectin. It is therefore unlikely that activated protein C inactivates the PAI-1/vitronectin complex and leads to PAI-1 depletion. Instead, an enormous increase in the release of t-PA by endothelial cells due to shock-induced hypoperfusion is the likely cause of increased fibrinolysis. These mechanisms are very similar to DIC with the fibrinolytic phenotype; however, the lack of evidence of intravascular clot formation rules out this hypothesis according to the theory proposed by this group.

Rationale

A recent review acknowledges that thrombin generation, hypofibrinogenemia, and endothelial dysfunction are observed in trauma-induced coagulopathies including ACOTS. This is very similar to the concept proposed by the two groups that expressed doubts in the concept of ACOTS [29]. Thus, the pathogenesis of ACOTS has been controversial for a decade since its announcement in 2007.

Objectives

The aim of this systematic review is to address the following questions on ACOTS: 1) Does activated protein C inhibit systemic thrombin generation? 2) Does activated protein C increase fibrinolysis through the neutralization of PAI-1? and 3) Are there established diagnostic criteria for ACOTS? The participants were trauma patients (P) who had their activated protein C or activated protein C-related coagulation and fibrinolysis markers measured (E) and who had been diagnosed with ACOTS or without it (non-ACOTS) using specific definitions (C). The outcomes were evidence that activated protein C inhibits coagulation and accelerates fibrinolysis and evidence of an established diagnostic method for ACOTS (O).

Methods

This systematic review was performed in accordance with the protocol of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocol (PRISMA-P) 2015 [30, 31]. The flow of information through the different phases of the systematic review was constructed based on the PRISMA Statement 2009 [32]. No systematic reviews have been conducted on this theme; thus, this is not an amendment of a previously completed protocol. At the point of completing the data extraction, this study did not meet the inclusion criteria of the International Prospective Register of Systematic Review (PROSPERO); thus, this systematic review was not registered.

The classifications shown in Table 1 were used in order to clarify the complicated terminology of trauma-induced coagulopathy in this systematic review [22]. Although other terms such as “acute coagulopathy of trauma” or “acute traumatic coagulopathy” etc. are now used to describe ACOTS, the original term, ACOTS, is mostly used in this systematic review. The other terms are used, as appropriate, when discussing the studies in which they are used.

Eligibility criteria

Study design

We included all studies, irrespective of whether they are prospective or retrospective in nature, with the exception of narrative reviews, current opinions, points of view, case reports, and case series.

Participants

We included human patients with trauma. Pediatric trauma patients were excluded.

Interventions

Studies that measured activated protein C or activated protein C-related coagulation and fibrinolysis markers in the blood were included. We also included studies that measured thrombin- and plasmin-related markers in the blood. Intervention studies were also included irrespective of the types of interventions. Studies that measured coagulation and fibrinolysis outside of the vessels using thromboelastgraphy or rotational thromboelastometry, which had no information on the coagulation and fibrinolysis markers in the circulation were excluded.

Comparators

Non-ACOTS patients and/or healthy individuals were used as controls.

Timing

In all of the studies that were included, the first blood sample was obtained within 12 h after injury.

Setting. The setting included emergency departments and intensive care units.

Language

We included articles that were written in English.

Information sources and search strategies

We searched the following electronic bibliographic databases: PubMed, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CSDR), and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL). We also manually searched the reference lists of selected studies. The search was limited to the English literature published from January 1, 2007 to May 22, 2017. The final date of the search was May 23, 2017. The following terms were used to obtain potentially eligible articles: trauma, traumatic, injury, injuries, coagulopathy, coagulopathies, disseminated intravascular coagulation, DIC, protein C, thrombin, procoagulant, PAI-1, and fibrinolysis. The abovementioned key words were used in combination as follows: (“protein C” OR thrombin OR procoagulant OR PAI-1 OR fibrinolysis OR coagulopathy OR coagulopathies OR “disseminated intravascular coagulation” OR DIC) AND (trauma OR traumatic OR injury OR injuries).

Data records

No specialized software programs were used for the management of the systematic review data. The extracted data were exported to Excel files (Office 2016 for Macintosh, Microsoft Japan) in the CSV format and then stored and managed. The titles and/or abstracts of studies retrieved using the search strategy and those from additional sources were screened independently by two of the review’s authors (TM and SG) to identify studies that potentially met the above-mentioned eligibility criteria. The full text of the potentially eligible studies was retrieved and independently assessed for eligibility by two of the review’s authors (TM and SG). Any disagreement between them over the eligibility of the studies was resolved through discussion with a third reviewer (TU).

Data items

A standardized, pre-piloted form was used to extract data from the included studies in orders to assess the study quality. The information that was extracted included: the study setting; the study population and the demographics and baseline characteristics of the patients; the study methodology; the definitions of trauma-induced coagulopathy including ACOTS, and other coagulopathies or the methods by which the conditions were diagnosed; the markers of coagulation and fibrinolysis that were measured; the levels of activated protein C; evidence of the activated protein C-mediated inhibition of thrombin (or surrogate markers of thrombin generation) and PAI-1; the outcomes; and the times at which the targeted markers were measured. One of the authors (SG) extracted the data, determined the validity of the extracted data, identified discrepancies in the extracted data and identified missing data. Issues were resolved through discussion with the second (TM) and third (TU) authors.

Outcomes and prioritization

Primary outcome. Evidence that activated protein C inhibited systemic thrombin generation by inactivating FVa and FVIIIa and evidence that activated protein C increased fibrinolysis through the neutralization of PAI-1 followed by the production of t-PA.

Secondary outcome. Evidence of established diagnostic method for ACOTS based on the activated protein C dynamics.

Risk of bias individual studies

This systematic review did not include a meta-analysis on the outcomes and the authors did not attempt to evaluate the outcome of the included population. Thus, the assessment of the risk of bias was performed at the study level and the body of evidence was not presented.

The study quality was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS), which scores the quality of non-randomized studies [33]. NOS has three domains based on the following: 1) the selection of the cohort, 2) the comparability of the cohorts and 3) the quality of outcome for cohort study, as well as 1) the selection of cases and controls, 2) the comparability of cases and controls and 3) the ascertainment of exposure for case-control study. NOS identifies quality with “stars”. A maximum of one star for each item within the selection and exposure/outcome categories and a maximum of two stars for comparability can be given in the NOS. The total maximum score is 9 stars. Ratings of≥ 7 were high; 4 to 6, moderate and 4 or less, low quality, were used in the present study [34].

Data synthesis

A quantitative synthesis would not have been appropriate because of the aim of this review. A systematic narrative synthesis was provided with the information presented in the text and tables to summarize and explain the characteristics and findings of the included studies. The narrative synthesis explored the relationships and the findings both within and among the included studies.

Meta-bias

We tried to avoid a publication biases and outcome reporting bias by submitting the results to an international journal and by clearly stating the primary and secondary outcomes.

Confidence of cumulative estimate

We did not construct a body of evidence.

Results

The included studies

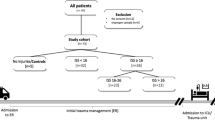

The flow of information through the different phases of this systematic review is presented in Fig. 1. Through these selection processes, 17 of 7613 studies met the inclusion criteria and were analyzed. Summary of the included studies are shown in Tables 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7. PRISMA-P 2015 checklist is shown as Additional file 1: Table S1 [31].

Study quality

All of the studies included were prospectively performed, but there were no randomized controlled studies. A clear control group or non-exposed cohort (non-ACOTS) had been established in seven of the studies, and data from normal healthy controls were presented in five studies. The overall quality of studies was low, with a mean score of 3.5 and a range of 1 to 7. In particular, the quality of the cohort studies was very low, with mean NOS score of 2.2. The assessment of the study quality using the NOS is shown in Additional file 2: Table S2.

Activated protein C (Tables 2, 3 and 4)

Only 7 studies directly measured the activated protein C level [35,36,37,38,39,40,41] and 1 study measured the prothrombinase activity as surrogate marker of function of activated protein C [42]. Thrombin generation was assessed in 4 studies and PAI-1 was measured in 3 studies. Three studies simultaneously measured activated protein C, thrombin generation, and PAI-1 [35, 38, 41].

The activated protein C levels of the ACOT and non-ACOT subjects did not differ to a statistically significant extent [35] or the activated protein C levels in the ACOTS were significantly decreased in comparison to the non-ACOTS [40]. The former study showed no differences in the levels of prothrombin fragment 1 + 2 (PF1 + 2), thrombin and antithrombin complex (TAT) or PAI-1 between ACOTS and non-ACOTS. Significant differences in the Injury Severity Score (ISS) and the diagnosis of ACOTS did not affect the levels of activated protein C, PF1 + 2, TAT, or PAI-1 [38]. Normal prothrombinase activity in ACOTS was associated with increased levels of soluble fibrin, a direct marker of thrombin generation and its activation [42].

Three studies confirmed elevated activated protein C levels in patients with ISS of > 15 and a base deficit of < 6, in patients with histone levels of > 50 AU, or in patients with prothrombin time international normalized ratio (PTINR)-based and activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT)-based coagulopathy. However, no results on the relationships between activated protein C and thrombin generation or activated protein C and PAI-1 were presented [36, 37, 39]. The higher levels of activated protein C in acute traumatic coagulopathy, in comparison to non-acute traumatic coagulopathy, were associated with the significant elevation of PF1 + 2 [41]. This study also confirmed that activated protein C levels did not affect the levels of PAI-1.

Finally, activated protein C is well known to be immediately inactivated by protein C inhibitor, α1-antitrypsin, α2-antiplasmin, and α2-macroglobulin in the circulation. Therefore, the methods of measurement are very important to consider when discussing the level and function of activated protein C in the circulation. As shown in Tables 2, 3 and 4, different methods of measuring activated protein C were used in eight studies, which may have affected the results of these studies. The validation of measurement methods used in each study is mandatory.

Thrombin generation and PAI-1 (Tables 5, 6 and 7)

Although they did not measure the levels of activated protein C, 9 studies investigated activated protein C-related markers, thrombin generation and PAI-1 [8,9,10, 43,44,45,46,47,48]. Three studies hypothesized, based on low protein C levels, that activated protein C contributes to the suppression of thrombin generation and hyperfibrinolysis via the inactivation of FVa and FVIIIa and the consumption of PAI-1, respectively [8,9,10]. However, none of the three studies showed direct evidences to support these hypotheses.

In contrast, systemic thrombin generation or tissue factor activity in the circulation were confirmed in acute coagulopathy of trauma [43], traumatic coagulopathy [44], and severely injured trauma patients [45, 46]. In patients with severe fibrinolysis, an increased t-PA level was not associated with any decreases in the PAI-1 levels. In addition, the PAI-1 levels were similar among the patients with normal, moderate, and severe fibrinolysis [46]. With regards to the mechanism underlying the increase in active t-PA without concomitant increase in active PAI-1 [47], one study suggested that a massive t-PA release overwhelms the free PAI-1 and that the degradation of PAI-1 by activated protein C is not responsible for increased fibrinolysis [48].

The definition and diagnostic criteria of ACOTS

As Tables 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7 show, no unified terminology, clear definition, or internationally agreed upon diagnostic criteria for ACOTS were used in the selected studies, which were published after ACOTS became an established pathophysiological condition of trauma-induced coagulopathy [11, 12].

Discussion

Activated protein C has both anticoagulant and profibrinolytic effects through the proteolytic inactivation of FVa and FVIIIa and through the activation of TAFI and the neutralization of PAI-1 [4, 5, 49]. Although these activities are important in normal physiological hemostasis at the injured site, the suggestion that the same properties are systemically active in pathological conditions such ACOTS is in doubt. Campbell et al. [50] suggested that the levels of activated protein C in ACOTS were insufficient to inactivate platelet and plasma FVa. Another in vitro study confirmed that 300 to 2000 ng/mL of activated protein C was needed to suppress activities of FV and FVIII, and to prolong PT and APTT [51]. These levels were extremely high in comparison to those observed in clinical studies, which indirectly shows that pathomechanisms of ACOTS are not robust [36, 37, 39].

Only 2 studies simultaneously compared the activated protein C and thrombin generation levels between ACOTS (acute traumatic coagulopathy) and non-ACOTS (non-acute traumatic coagulopathy) [35, 41]. Thrombin generation (PF1 + 2 or TAT) was preserved without changes in the activated protein C levels [35] or was significantly increased with high activated protein C levels being observed [41]. One study confirmed normal prothrombinase activity with markedly elevated thrombin generation [42]. Importantly, in studies that measured activated protein C levels, the levels were reported to be inconsistently normal, decreased, or elevated [35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42]. Although the activated protein C levels were not measured, the clinical studies consistently showed significant systemic thrombin generation in ACOTS and severely injured trauma patients [43,44,45,46]. These results suggest that - irrespective of activated protein C levels - systemic thrombin generation is increased immediately after trauma, especially in ACOTS and in patients with severe trauma.

Two studies simultaneously compared the activated protein C and PAI-1 levels between ACOTS (acute traumatic coagulopathy) and non-ACOTS (non-acute traumatic coagulopathy) [35, 41]. There were no differences in the levels of PAI-1 between patients with and without ACOTS or acute traumatic coagulopathy, irrespective of the activated protein C levels. Another study confirmed the same results in ACOTS with severe head and neck, and extracranial injuries [38]. Although the activated protein C levels was not measured, severe fibrinolysis, evidenced by increased levels of plasmin and α2-antiplasmin complex and t-PA, was not associated with decreased PAI-1 levels [46]. One study clearly demonstrated that the decrease in the PAI-1 levels in patient with trauma-induced coagulopathy was driven by an increase in t-PA, rather than by the degradation of PAI-1 by activated protein C [48]. These results suggest that activated protein C is highly unlikely to neutralize PAI-1.

A PT ratio of > 1.2 was announced as a clinically relevant definition of acute traumatic coagulopathy [52]. However, only two studies used this as diagnostic criteria for ACOTS [40, 42]. As shown in Tables 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7, various criteria were used to diagnose coagulopathy in the studies that were selected for this systematic review; furthermore, various names were used to refer to the conditions. This makes the collection of uniform patients group very difficult. As a consequence, the evidence to support a uniform concept of ACOTS is very fragile.

The main pathological definition of ACOTS is the activated protein C-mediated inactivation of FVa and FVIIIa, which stops the generation of thrombin. Thus, the APTT that represents coagulation pathway including FV and FVIII, but not PT, is considered to be more suitable for the diagnosis of ACOTS [20]. The lack of a clear pathological definition and diagnostic criteria based on activated protein C dynamics leads to these authors to be skeptical of the existence of the condition referred to as ACOTS.

This systematic review failed to establish hypotheses or complete the aims stated in the Objective section.

Conclusions

This systematic review demonstrated that there have been no studies that showed the direct cause and effect relationships between activated protein C and the suppression of systemic thrombin generation or between activated protein C and increased fibrinolysis via the neutralization of PAI-1. Systemic thrombin generation was always increased and increased fibrinolysis was observed independently from the PAI-1 levels in patients with ACOTS. The lack of a clear definition and diagnostic criteria, and various terminologies that are used to refer to ACOTS may be one of the reasons for these results. This systematic review denies pathophysiological definition of ACOTS that was proposed in 2007 and concludes that the condition that is referred to as “ACOTS” based on activated C dynamics unlikely to exist.

Key messages

-

None of the studies searched in our systematic review showed direct cause and effect relationships between activated protein C and the suppression of coagulation and increased fibrinolysis in ACOTS.

-

The lack of a clear definition and diagnostic criteria, and various terminologies that are used to refer to ACOTS may be one of the reasons for these results.

Abbreviations

- ACOTS:

-

Acute coagulopathy of trauma-shock (ACOTS)

- ACT:

-

Acute coagulopathy of trauma

- AIS:

-

Abbreviated injury scale

- APTT:

-

Activated partial thromboplastin time

- AT:

-

Antithrombin

- ATC:

-

Acute traumatic coagulopathy

- BD:

-

Base deficit

- DIC:

-

Disseminated intravascular coagulation

- ED:

-

Emergency department

- EPCR:

-

Endothelial protein C receptor

- FDP:

-

Fibrin/Fibrinogen degradation products

- FgDP:

-

Fibrinogen degradation products

- FVa:

-

Activated Factor V

- FVIIIa:

-

Activated Factor VIII

- ISS:

-

Injury Severity Score

- ISTH:

-

International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis

- iTBI:

-

Isolated traumatic brain injury

- MAP:

-

Mean arterial pressure

- NOS:

-

Newcastle-Ottawa Scale

- PAI-1:

-

Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1

- PAP:

-

Plasmin α2-antiplasmin complex

- PF1+2:

-

Prothrombin fragment 1+2

- PRISMA-P:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocol

- PROSPERO:

-

International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews

- PT:

-

Prothrombin time

- PTINR:

-

Prothrombin time international normalized ratio

- ROTEM:

-

Rotational thromboelastometry

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- sTBI:

-

Severe traumatic brain injury

- sTM:

-

Soluble thrombomodulin

- TAFI:

-

Thrombin-activatable fibrinolysis inhibitor

- TAT:

-

Thrombin and antithrombin complex

- TEG:

-

Thromboelastography

- TFPI:

-

Tissue factor pathway inhibitor

- t-PA:

-

Tissue-type plasminogen activator

References

Esmon CT, Xu J, Lupu F. Innate immunity and coagulation. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9:182–8.

Engelmann B, Massberg S. Thrombosis as an intravascular effector of innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:34–45.

Gando S, Otomo Y. Local hemostasis, immunothrombosis, and systemic disseminated intravascular coagulation in trauma and traumatic shock. Crit Care. 2015;19:72.

Griffin JH, Fernandez JA, Gale AJ, Moisner LO. Activated protein C. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5(Suppl. 1):73–80.

Bajzar L, Nesheim ME, Tracy PB. The profibrinolytic effect of activated protein C in clot formed from plasma is TAFI-dependent. Blood. 1996;88:2093–100.

Hoffman M, Monroe DM. A cell-based model of hemostasis. Thromb Haemost. 2001;85:958–65.

Brohi K, Cohen MJ, Davenport RA. Acute coagulopathy of trauma: mechanism, identification and effect. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2007;13:680–5.

Brohi K, Cohen MJ, Ganter MT, Matthay MA, Mackersie RC, Pittet JF. Acute traumatic coagulopathy: initiated by hypoperfusion: modulated through the protein C pathway? Ann Surg. 2007;245:812–8.

Cohen MJ, Brohi K, Ganter MT, Manley GT, Mackersie RC, Pittet JF. Early coagulopathy after traumatic brain injury: the role of hypoperfusion and the protein C pathway. J Trauma. 2007;63:1254–61.

Brohi K, Cohen MJ, Ganter MT, Schultz MJ, Levi M, Mackersie RC, Pittet JF. Acute coagulopathy of trauma: hypoperfusion induces systemic anticoagulation and hyperfibrinolysis. J Trauma. 2008;64:1211–7.

Hess JR, Brohi K, Dutton RP, Hauser CJ, Holcomb JB, Kluger Y, Mackway-Jones K, Parr MJ, Rizoli SB, Yukioka T, et al. The coagulopathy of trauma: a review of mechanisms. J Trauma. 2008;65:748–54.

Bouillon B, Brohi K, Hess JR, Holcomb JB, Parr MJ, Hoyt DB. Educational initiative on critical bleeding in trauma: Chicago, July 11-13, 2008. J Trauma. 2010;68:225–30.

Frith D, Brohi K. The acute coagulopathy of trauma shock: clinical relevance. Surgeon. 2010;8:159–63.

Frith D, Davenport R, Brohi K. Acute traumatic coagulopathy. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2012;25:229–34.

Davenport R. Pathogenesis of acute traumatic coagulopathy. Transfusion. 2013;53(Suppl 1):s23–7.

Cohen MJ. Acute traumatic coagulopathy: clinical characterization and mechanistic investigation. Thromb Res. 2014;133(Suppl 1):S25–7.

Maegele M, Schöchl H, Cohen MJ. An update on the coagulopathy of trauma. Shock. 2014;41(Suppl 1):s21–5.

Taylor FB Jr, Toh CH, Hoots WK, Wada H, Levi M, Scientific Subcommittee on Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (DIC) of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH). Towards definition, clinical and laboratory criteria, and a scoring system for disseminated intravascular coagulation. Thromb Haemost. 2001;86:1327–30.

Gando S, Sawamura A, Hayakawa M. Trauma, shock, and disseminated intravascular coagulation: lessons from the classical literature. Ann Surg. 2011;254:10–9.

Gando S, Wada H, Thachil J, Scientific and Standardization Committee on DIC of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH). Differentiating disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) with the fibrinolytic phenotype from coagulopathy of trauma and acute coagulopathy of trauma-shock (COT/ACOTS). J Thromb Haemost. 2013;11:826–35.

Gando S. Hemostasis and thrombosis in trauma patients. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2015;41:26–34.

Gando S, Hayakawa M. Pathophysiology of trauma-induced coagulopathy and management of critical bleeding requiring massive transfusion. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2016;42:155–65.

Gando S. Disseminated intravascular coagulation. In: Gonzalez E, Moore HB, Moore EE, editors. Trauma induced coagulopathy. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing AG; 2016. p. 195–217.

Gando S, Levi M, Toh CH. Disseminated intravascular coagulation. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16037.

Cap A, Hunt B. Acute traumatic coagulopathy. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2014;20:638–45.

Dobson GP, Letson HL, Sharma R, Sheppard FR, Cap AP. Mechanisms of early trauma-induced coagulopathy: the clot thickens or not? J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;79:301–9.

Cap A, Hunt BJ. The pathogenesis of traumatic coagulopathy. Anaesthesia. 2015;70(Suppl 1):96–101.

Meledeo MA, Herzig MC, Bynum JA, Wu X, Ramasubramanian AK, Darlington DN, Reddoch KM, Cap AP. Acute traumatic coagulopathy: the elephant in a room of blind scientists. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017;82(6S Suppl 1):S33–40.

Davenport RA, Brohi K. Cause of trauma-induced coagulopathy. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2016;29:212–9.

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, Shekelle P, Stewart LA, PRISMA-P Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4:1.

Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, Shekelle P, Stewart LA, PRISMA-P Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ. 2015;349:g7647.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097.

Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. Accessed 21 Mar 2018.

Muscedere J, Waters B, Varambally A, Bagshaw SM, Boyd JG, Maslove D, Sibley S, Rockwood K. The impact of frailty on intensive care unit outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43:1105–22.

Johansson PI, Sørensen AM, Perner A, Welling KL, Wanscher M, Larsen CF, Ostrowski SR. Disseminated intravascular coagulation or acute coagulopathy of trauma shock early after trauma? An observational study. Crit Care. 2011;15:R272.

Cohen MJ, Call M, Nelson M, Calfee CS, Esmon CT, Brohi K, Pittet JF. Critical role of activated protein C in early coagulopathy and later organ failure, infection and death in trauma patients. Ann Surg. 2012;255:379–85.

Kutcher ME, Xu J, Vilardi RF, Ho C, Esmon CT, Cohen MJ. Extracellular histone release in response to traumatic injury: implications for a compensatory role of activated protein C. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73:1389–94.

Genét GF, Johansson PI, Meyer MA, Sølbeck S, Sørensen AM, Larsen CF, Welling KL, Windeløv NA, Rasmussen LS, Ostrowski SR. Trauma-induced coagulopathy: standard coagulation tests, biomarkers of coagulopathy, and endothelial damage in patients with traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2013;30:301–6.

Cohen MJ, Kutcher M, Redick B, Nelson M, Call M, Knudson MM, Schreiber MA, Bulger EM, Muskat P, Alarcon LH, et al; PROMMTT Study Group. Clinical and mechanistic drivers of acute traumatic coagulopathy. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2013; 75(Suppl 1):S40–S47.

Jesmin S, Gando S, Wada T, Hayakawa M, Sawamura A. Activated protein C does not increase in the early phase of trauma with disseminated intravascular coagulation: comparison with acute coagulopathy of trauma-shock. J Intensive Care. 2016;4:1.

Davenport RA, Guerreiro M, Frith D, Rourke C, Platton S, Cohen M, Pearse R, Thiemermann C, Brohi K. Activated protein C drives the hyperfibrinolysis of acute traumatic coagulopathy. Anesthesiology. 2017;126:115–27.

Yanagida Y, Gando S, Sawamura A, Hayakawa M, Uegaki S, Kubota N, Homma T, Ono Y, Honma Y, Wada T, Jesmin S. Normal prothrombinase activity, increased systemic thrombin activity, and lower antithrombin levels in patients with disseminated intravascular coagulation at an early phase of trauma: comparison with acute coagulopathy of trauma-shock. Surgery. 2013;154:48–57.

Dunbar NM, Chandler WL. Thrombin generation in trauma patients. Transfusion. 2009;49:2652–60.

Chandler WL. Procoagulant activity in trauma patients. Am J Clin Pathol. 2010;134:90–6.

Tauber H, Innerhofer P, Breitkopf R, Westermann I, Beer R, El Attal R, Strasak A, Mittermayr M. Prevalence and impact of abnormal ROTEM(R) assays in severe blunt trauma: results of the ‘Diagnosis and Treatment of Trauma-Induced Coagulopathy (DIA-TRE-TIC) study. Br J Anaesth. 2011;107:378–87.

Raza I, Davenport R, Rourke C, Platton S, Manson J, Spoors C, Khan S, De’Ath HD, Allard S, Hart DP, et al. The incidence and magnitude of fibrinolytic activation in trauma patients. J Thromb Haemost. 2013;11:307–14.

Cardenas JC, Matijevic N, Baer LA, Holcomb JB, Cotton BA, Wade CE. Elevated tissue plasminogen activator and reduced plasminogen activator inhibitor promote hyperfibrinolysis in trauma patients. Shock. 2014;41:514–21.

Chapman MP, Moore EE, Moore HB, Gonzalez E, Gamboni F, Chandler JG, Mitra S, Ghasabyan A, Chin TL, Sauaia A, Banerjee A, Silliman CC. Overwhelming tPA release, not PAI-1 degradation, is responsible for hyperfibrinolysis in severely injured trauma patients. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016;80:16–23. discussion 23-5

Sakata Y, Loskutoff DJ, Gladson CL, Heckman C, Griffin JH. Mechanism of protein C-dependent clot lysis: role of plasminogen activator inhibitor. Blood. 1986;68:1218–23.

Campbell JE, Meledeo MA, Cap AP. Comparative response of platelet fV and plasma fV to activated protein C and relevance to a model of acute traumatic coagulopathy. PLoS One. 2014;9:e99181.

Howard BM, Kornblith LZ, Cheung CK, Kutcher ME, Miyazawa BY, Vilardi RF, Cohen MJ. Inducing acute traumatic coagulopathy in vitro: the effects of activated protein C on healthy human whole blood. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0150930.

Frith D, Goslings JC, Gaarder C, Maegele M, Cohen MJ, Allard S, Johansson PI, Stanworth S, Thiemermann C, Brohi K. Definition and drivers of acute traumatic coagulopathy: clinical and experimental investigations. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8:1919–25.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

No funding or financial support was used for this study.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TM, SG, TU conducted to conception and design of this systematic review. TM and SG conducted literature search and contributed to data collection. SG extracted the data, synthesized, and interpreted with discussion of TM and TU. TM and TU supervised all processes of this review. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable for this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable for this study.

Competing interests

Gando S received payment for lectures from Asahi Kasei Pharma, which is not related to present study. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests on association with the present study.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Table S1. PRISMA-P 2015 checklist: recommended items to address in a systematic review protocol. (PDF 189 kb)

Additional file 2:

Table S2. Assessment of study quality using the NOS system. (PDF 102 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Gando, S., Mayumi, T. & Ukai, T. Activated protein C plays no major roles in the inhibition of coagulation or increased fibrinolysis in acute coagulopathy of trauma-shock: a systematic review. Thrombosis J 16, 13 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12959-018-0167-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12959-018-0167-3