Abstract

Background

Inflammation plays a critical role in the development and progression of cancers. The advanced lung cancer inflammation index (ALI) is thought to be able to reflect systemic inflammation better than current biomarkers. However, the prognostic significance of the ALI in various types of cancer remains unclear. Our meta-analysis aimed to comprehensively investigate the relationship between the ALI and oncologic outcomes to help physicians better assess the prognosis of cancer patients.

Methods

The PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, China National Knowledge Infrastructure, and Wanfang databases were searched for relevant studies. Hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were calculated and pooled from the included studies. Furthermore, a sensitivity analysis was performed to evaluate the reliability of the articles. Finally, Begg’s test, Egger’s test, and the funnel plot were applied to assess the significance of publication bias.

Results

In total, 1736 patients from nine studies were included in our meta-analysis. The median cutoff value for the ALI was 23.2 (range, 15.5–37.66) in the analyzed studies. The meta-analysis showed that there was a statistically significant relationship between a low ALI and worse overall survival (OS) in various types of cancer (HR = 1.70, 95% CI = 1.41–1.99, P < 0.001). Moreover, results from subgroup meta-analysis showed that the ALI had a significant prognostic value in non-small cell lung cancer, small cell lung cancer, colorectal cancer, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, and diffuse large B cell lymphoma (P < 0.05 for all).

Conclusions

These results showed that a low ALI was associated with poor OS in various types of cancer, and the ALI could act as an effective prognostic biomarker in cancer patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Cancer is one of the major causes of death worldwide [1]. In 2018, there were more than 18 million new cases diagnosed and 9.5 million cancer-related deaths [2]. Although great progress in treating cancer has been made over the past decade, the clinical outcome of cancer patients remains poor [3]. Therefore, identifying an effective prognostic index for patient survival could help clinicians adopt better preventive and therapeutic treatments, which could further reduce cancer mortality [4, 5].

Growing evidence indicates that cancer-related inflammation plays a critical role in the development and progression of various types of cancer [6,7,8]. At the early stages of tumorigenesis, various inflammatory cells and proinflammatory cytokines are activated, and these promote the formation of new blood vessels and lymphatic ducts, providing a tumor microenvironment beneficial to the growth and differentiation of tumor cells [9]. At later stages, cancer-related inflammation can destroy the function of immune cells, leading to a pro-metastatic environment [10,11,12,13]. Therefore, inflammatory markers are expected to be valuable prognostic biomarkers in cancer. For example, as a comprehensive index based on two blood factors, an increased neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) is associated with a strong inflammatory response and a weak immune response, implying its effective prognostic value [14,15,16].

Cachexia in cancer patients is the result of the chronic systemic inflammatory response and often indicates a poor outcome for cancer patients [17, 18]. Sarcopenia is an important part of cancer cachexia syndrome and is associated with poor prognosis in multiple cancers, such as lung, gastrointestinal, and hepatopancreatobiliary malignancies [19, 20]. Previous studies have reported that the body mass index (BMI) has a close association with the sarcopenic status [21]. Serum albumin (ALB), which reflects the nutritional status, has also been proven to be associated with poor prognosis in many cancers [22,23,24]. A new inflammation-related marker, the advanced lung cancer inflammation index (ALI), was first determined to be an effective prognostic index in metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [25]. The ALI combines the BMI, ALB, and the NLR (BMI × ALB/NLR). Therefore, the ALI has the potential to reflect systemic inflammation better than other biomarkers because it merges multiple nutritional and inflammatory indicators. Thus, it may have a better predictive value than other prognostic biomarkers in cancer patients.

However, a pooled study that analyzes the association between the ALI and clinical outcomes of patients with malignant diseases has not been systematically performed. Our meta-analysis aimed to explore the prognostic impact of the ALI in cancer patients, helping physicians predict clinical outcomes more effectively and easily and assisting them in the timely adjustment of therapeutic regimens, which further reduces mortality.

Methods

Search strategy

This study was performed according to the recommendations of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement (Additional file 1). The PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, China National Knowledge Infrastructure, and Wanfang databases were searched for relevant studies without language, publication, or time restrictions (the publication period included database establishment to March 15, 2019). The following search terms were applied: “advanced lung cancer inflammation index” OR “ALI” OR “BMI x ALB / NLR” OR “BMI x serum albumin / NLR” OR “neutrophil-to-lymphocyte” AND “cancer” OR “tumor” OR “carcinoma.” Reference lists of the included articles were also scanned to identify potentially related studies.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The following criteria were used for inclusion in this meta-analysis:

-

(i)

Studies examining the association between the ALI and prognosis in patients with any type of cancer.

-

(ii)

Sufficient data provided to calculate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) for the relationship between the ALI and overall survival (OS) in cancer patients.

-

(iii)

The cutoff value of the ALI was clear.

-

(iv)

If more than one article referred to the same population, only the study that included the most cases or the latest publication was included.

The following studies were excluded from the meta-analysis:

-

(i)

Studies based on animal or cell experiments

-

(ii)

Meta-analyses, reviews, case reports, or reports based on expert experience

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two authors (HX and HSH) independently extracted the following data from all included studies:

-

(i)

Basic information, including authors’ names, publication year, cancer type, country, study period, characteristics of the study population (sample size, age, and gender), survival type, treatments, clinical stage, cutoff value, cutoff selection, and study design

-

(ii)

Statistical indicators, including HRs and corresponding 95% CIs for OS, from multivariate or univariate analysis or estimated from Kaplan-Meier survival curves using previously described methods if the HR could not be obtained directly [26]

The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) was used to assess the quality of included studies, and a score ≥ 6 was considered an indicator of a high-quality study, whereas a score < 6 indicated a low-quality study [27]. Two reviewers (CJ and WY) independently evaluated the quality of the eligible studies, and all disagreements were resolved through discussion with a third author (ZXL).

Statistical analysis

Stata software (version 12.0; Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA) was used to analyze the data in our study. HRs and 95% CIs were used to evaluate the association between the ALI and OS in cancer patients. A pooled HR > 1 was regarded as an indicator of poor prognosis in groups with a low ALI. The impact of the ALI on survival was considered statistically significant if the corresponding 95% CI for the summary HR did not overlap 1 unit. The Cochran’s Q test and I2 statistics were used to analyze heterogeneity between studies; P < 0.05 or I2 > 50% suggested significant heterogeneity among the included studies. If the homogeneity was significant, a random effects model was used. Otherwise, a fixed effects model was used [28]. Subgroup analyses were also performed on the basis of the median age, sample size, ethnicity, pathological type, clinical stage, treatment strategy, and ALI cutoff values. To explore the robustness of the overall statistical results, we performed a sensitivity analysis. Potential publication bias was assessed using Begg’s test, Egger’s test, and funnel plot. All P values were two-sided, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Study selection and characteristics

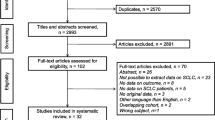

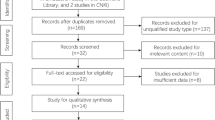

The process of study selection is shown in Fig. 1. Ultimately, nine studies met our selection criteria; after excluding duplicated studies and reviewing the full texts of the manuscripts [25, 29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36], a total of 1736 cases were included. With respect to prognostic outcomes, nine studies reported OS, two studies reported progression-free survival, and one study reported disease-free survival. Among the included studies, four types of tumors were investigated, including lung cancer, colorectal cancer, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, and diffuse large B cell lymphoma. The cutoff value of the ALI in the included studies ranged from 15.5 to 37.66, with a median of 23.2. The characteristics and demographic data of all included studies are presented in Table 1.

For quality assessment, the nine studies were evaluated using the NOS, and the scores were all ≥ 6, indicating that the included studies were all high-quality studies (Additional file 2).

Relationship between the ALI and OS in various cancer types

As shown in Fig. 2, there were nine studies with 1736 cases demonstrating the association between the ALI and OS in cancer patients. Our results indicated that a low ALI was significantly related to a poor outcome in cancer patients (HR = 1.70, 95% CI = 1.41–1.99, P < 0.001). Considering that heterogeneity was not obvious among the studies, a fixed effects model was applied.

In addition, subgroup analyses stratified by the median age, sample size, ethnicity, pathological type, clinical stage, treatments, and cutoff for ALI were also performed (Table 2). The results showed that a lower ALI was a significant predictive index of OS in NSCLC (HR = 1.55, 95% CI = 1.08–2.02, P < 0.001), small cell lung cancer (SCLC) (HR = 1.64, 95% CI = 1.24–2.05, P < 0.001), colorectal cancer (HR = 2.77, 95% CI = 1.77–4.34, P < 0.001), head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HR = 2.23, 95% CI = 1.12–4.55, P = 0.011), and diffuse large B cell lymphoma (HR = 2.64, 95% CI = 1.54–5.97, P = 0.019). In terms of patient age and sample size, the ALI had a significant prognostic value for cancer patients regardless of the median patient age (≥ 60 years and < 60 years) or sample size (≥ 170 or < 170) (P < 0.001 for all). When studies were divided into those performed in Asian, North American, and European countries, the ALI was significantly related to OS only in studies from Asia and North America (P < 0.001 for both). When tumor stage was considered, the results showed that a lower ALI was a risk factor in patients with metastatic or mixed-stage tumors (P < 0.001 for both) but not in patients with non-metastatic disease. When performing subgroup analysis by treatment type, the association was still significant in patients who did not undergo surgery and those who underwent surgery (P < 0.001 for all). Furthermore, the ALI was indicated to be an effective prognostic factor when the cutoff for the ALI was > 23.2 and < 23.2 (P < 0.001 for all).

Sensitivity analysis and publication bias

Sensitivity analysis was used to detect the robustness of these results, which showed that the pooled results were not altered by any one study, indicating that our conclusions are relatively reliable (Fig. 3).

Both Begg’s test (P = 0.048) and Egger’s test (P = 0.014) indicated that publication bias was present among the studies. An asymmetric funnel plot also proved this conclusion (Fig. 4).

Discussion

A comprehensive search was conducted for published articles exploring the prognostic effect of the ALI on the survival outcomes of cancer patients. A total of 1736 cases from nine studies were included in our meta-analysis. The results of our study indicated that a low ALI was associated with worse prognosis (HR = 1.70, 95% CI = 1.41–1.99, P < 0.001). Furthermore, we observed consistent results in subgroups of various cancer types, including NSCLC, SCLC, colorectal cancer, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, and diffuse large B cell lymphoma. In short, the ALI could act as a predictive factor for clinical outcomes in cancer patients.

Cancer progression is associated with a high level of systemic inflammation [37]. Many studies have shown that serum inflammatory markers, such as C-reactive protein (CRP) [38,39,40], the NLR [41,42,43], the platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio [44, 45], the Glasgow Prognostic Score (GPS) [46, 47], and the systemic immune-inflammation index [48, 49], are related to the clinical outcomes of cancer patients. Low body weight and hypoproteinemia are also both associated with persistent systemic inflammation [50,51,52], and the BMI and ALB have also been confirmed as effective prognostic markers for cancer patients [53, 54]. The ALI is an index developed on the basis of these current markers and could provide important prognostic information for cancer patients [55]. In addition, the ALI has been shown to be superior to other related inflammatory indicators used as predictive biomarkers in cancer. Kobayashi et al. examined the prognostic value of the ALI in lung adenocarcinoma patients and concluded that the ALI was an independent predictor of OS (HR = 7.55, 95% CI = 3.03–18.8) and had a better prognostic value than the NLR (HR = 3.91, 95% CI = 1.36–11.26) and GPS (HR = 1.24, 95% CI = 0.32–4.77) [33]. Tomita et al. revealed that the preoperative ALI and CRP levels were significant predictors of OS in patients with NSCLC and that the ALI (HR = 0.436, 95% CI = 0.278–0.679) was superior to the CRP level (HR = 0.631, 95% CI = 0.403–0.993) as a prognostic index [56]. The univariate analysis from Feng et al.’s study showed that the ALI, BMI, ALB, and NLR were significantly related to cancer-specific survival in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma patients [57]. However, the multivariate analysis demonstrated that only an ALI ≥ 18 was an independent prognostic factor of better cancer-specific survival (HR = 1.433, 95% CI = 1.048–1.959), but the NLR (HR = 1.436, 95% CI = 0.938–2.198), BMI (HR = 1.060, 95% CI = 0.752–1.494), and ALB (HR = 1.285, 95% CI = 0.905–1.824) were not. In summary, as a composite index combining the inflammatory state (NLR) and the nutritional state (BMI and ALB), the ALI may have a better discriminatory value than other biomarkers and remains a novel and effective inflammatory prognostic factor.

A subgroup analysis showed that, although the ALI had prognostic value in most subgroups, there was no difference in OS based on the ALI in European patients and in patients with non-metastatic disease. There are several possible reasons for these findings. First, the European subgroup contained a small number of studies (only two studies) and a small sample size. Second, the BMI, ALB, and NLR, which are components of the ALI, seem to have better prognostic value in advanced stages of cancer [58,59,60]. Therefore, the prognostic effect of the ALI on survival outcomes may be affected by the cancer stage. In the future, more data are needed in different stages of cancer to investigate the prognostic role of the ALI in different types of tumors, considering that the number of articles currently available is small.

Our study inevitably had some limitations. First, all of the studies included in this meta-analysis were retrospective, and the results may have thus been subject to potential bias. Second, confounding factors, such as the levels of tumor markers and history of chemoradiotherapy, might also affect the HR of the ALI in cancer patients; such an effect cannot be explored via subgroup analysis because the studies that were included did not provide sufficient information. Third, the cutoff value of the ALI was not uniform in different studies. Finally, publication bias existed in the studies that were included in our meta-analysis, which may be attributable to failure in publishing studies with negative results or with other variables.

Conclusions

In summary, our study revealed that a low ALI was significantly correlated with worse OS in cancer patients. Therefore, the ALI could be a reliable predictor for prognosis in cancer patients, providing consistent results for different cancer types. In the future, more large-scale, prospective, well-designed studies are needed to verify the association of the cutoff values of the ALI and tumor stage with the prognostic features of the ALI for patients with different types of cancer.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Abbreviations

- 95% CI:

-

95% confidence interval

- ALB:

-

Serum albumin

- ALI:

-

Advanced lung cancer inflammation index

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- GPS:

-

Glasgow Prognostic Score

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- NLR:

-

Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio

- NOS:

-

Newcastle-Ottawa Scale

- NSCLC:

-

Non-small cell lung cancer

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- SCLC:

-

Small cell lung cancer

References

Rebecca L, Siegel MPH, Kimberly D, Ahmedin J. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(1):7–34.

Ferlay J, Colombet M, Soerjomataram I, Mathers C, Parkin DM, Piñeros M, Znaor A, Bray F. Estimating the global cancer incidence and mortality in 2018: GLOBOCAN sources and methods. Int J Cancer. 2019;144(8):1941–53.

Piao J, Zhu L, Sun J, Li N, Dong B, Yang Y, Chen L. High expression of CDK1 and BUB1 predicts poor prognosis of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Gene. 2019;701:15–22.

Zhang Y, Chen B, Wang L, Wang R, Yang X. Systemic immune-inflammation index is a promising noninvasive marker to predict survival of lung cancer: a meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98(3):13788.

Abbas M, Habib M, Naveed M, Karthik K, Dhama K, Shi M, Dingding C. The relevance of gastric cancer biomarkers in prognosis and pre- and post- chemotherapy in clinical practice. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;95:1082–90.

Elinav E, Nowarski R, Thaiss CA, Hu B, Jin C, Flavell RA. Inflammation-induced cancer: crosstalk between tumours, immune cells and microorganisms. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:759–71.

Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell. 2010;140(6):883–99.

Diakos CI, Charles KA, McMillan DC, Clarke SJ. Cancer-related inflammation and treatment effectiveness. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(11):493–503.

Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature. 2002;420:860–7.

Minardi D, Scartozzi M, Montesi L, Santoni M, Burattini L, Bianconi M, Lacetera V, Milanese G, Cascinu S, Muzzonigro G. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio may be associated with the outcome in patients with prostate cancer. Springerplus. 2015;4:255.

Tang H, Lu W, Li B, Li C, Xu Y, Dong J. Prognostic significance of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in biliary tract cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2017;8(22):36857–68.

Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, Balkwill F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature. 2008;454(7203):436–44.

Balkwill F, Mantovani A. Inflammation and cancer: back to Virchow? Lancet. 2001;357(9255):539–45.

Wang Z, Zhan P, Lv Y. Prognostic role of pretreatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with systemic therapy: a meta-analysis. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2019;8(3):214–26.

Moon G, Noh H, Cho IJ, Lee JI, Han A. Prediction of late recurrence in patients with breast cancer: elevated neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR) at 5 years after diagnosis and late recurrence. Breast Cancer. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12282-019-00994-z.

Ku JY, Roh JL, Kim SB, Choi SH, Nam SY, Kim SY. Prognostic value of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in older patients with head and neck cancer. J Geriatr Oncol. 2019:1879–4068. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2019.06.013.

McMillan DC. Systemic inflammation, nutritional status and survival in patients with cancer. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2009;12(3):223–6.

Cole CL, Kleckner IR, Jatoi A, Schwarz EM, Dunne RF. The role of systemic inflammation in cancer-associated muscle wasting and rationale for exercise as a therapeutic intervention. JCSM Clin Rep. 2018;3(2):e00065.

Kim EY, Kim YS, Seo JY, Park I, Ahn HK, Jeong YM, Kim JH, Kim N. The relationship between sarcopenia and systemic inflammatory response for cancer cachexia in small cell lung cancer. PLoS One. 2016;11(8):161125.

Kim EY, Kim YS, Park I, Ahn HK, Cho EK, Jeong YM. Prognostic significance of CT-determined sarcopenia in patients with small-cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2015;10(12):1795–9.

Min KK, Chul JH, Soo L. Differences among skeletal muscle mass indices derived from height-, weight-, and body mass index-adjusted models in assessing sarcopenia. Korean J Intern Med. 2016;31(4):643–50.

Oki S, Toiyama Y, Okugawa Y, Shimura T, Okigami M, Yasuda H, Fujikawa H, Okita Y, Yoshiyama S, Hiro J, Kobayashi M, Ohi M, Araki T, Inoue Y, Mohri Y, Kusunoki M. Clinical burden of preoperative albumin-globulin ratio in esophageal cancer patients. Am J Surg. 2017;214(5):891–8.

Yamashita K, Ushiku H, Katada N, Hosodaa K, Moriyaa H, Mienoa H, Kikuchia S, Hoshib K, Watanabea M. Reduced preoperative serum albumin and absence of peritoneal dissemination may be predictive factors for long-term survival with advanced gastric cancer with positive cytology test. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015;41:1324–32.

Lai CC, You JF, Yeh CY, Chen JS, Tang R, Wang JY, Chin CC. Low preoperative serum albumin in colon cancer: a risk factor for poor outcome. Int J Color Dis. 2011;26(4):473–81.

Jafri SH, Shi R, Mills G. Advance lung cancer inflammation index (ALI) at diagnosis is a prognostic marker in patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): a retrospective review. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:158.

Tierney JF, Stewart LA, Ghersi D, Burdett S, Sydes MR. Practical methods for incorporating summary time-to-event data into meta-analysis. Trials. 2007;8:16.

Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25(9):603–5.

Asimit J, Day-Williams A, Zgaga L, Rudan I, Boraska V, Zeggini E. An evaluation of different meta-analysis approaches in the presence of allelic heterogeneity. Eur J Hum Genet. 2012;20(6):709–12.

He X, Zhou T, Yang Y, Hong S, Zhan J, Hu Z, Fang W, Qin T, Ma Y, Zhao Y, Cheng Z, Huang Y, Zhao H, Yang G, Zhang L. Advanced lung cancer inflammation index, a new prognostic score, predicts outcome in patients with small-cell lung cancer. Clin Lung Cancer. 2015;16(6):165–71.

Kim EY, Kim N, Kim YS, Seo JY, Park I, Ahn HK, Jeong YM, Kim JH. Prognostic significance of modified advanced lung cancer inflammation index (ALI) in patients with small cell lung cancer_ comparison with original ALI. PLoS One. 2016;11(10):164056.

Park YH, Yi HG, Lee MH, Kim CS, Lim JH. Prognostic value of the pretreatment advanced lung cancer inflammation index (ALI) in diffuse large b cell lymphoma patients treated with R-CHOP chemotherapy. Acta Haematol. 2017;137(2):76–85.

Bacha S, Sghaier A, Habibech S, Cheikhrouhou S, Racil H, Chaouch N, Chabbou A, Megdiche ML. Advanced lung cancer inflammation index: a prognostic score in patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. Tunis Med. 2017;95(11):976–81.

Kobayashi S, Karube Y, Inoue T. Advanced lung cancer inflammation index predicts outcomes of patients with pathological stage IA lung adenocarcinoma following surgical resection. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2018; https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/atcs/advpub/0/advpub_oa.18-00158/_article.

Tomita M, Ayabe T, Maeda R, Nakamura K. Comparison of inflammation-based prognostic scores in patients undergoing curative resection for non-small cell lung cancer. World J Oncol. 2018;9(3):85–90.

Shibutani M, Maeda K, Nagahara H, Fukuoka T, Matsutani S, Kimura K, Amano R, Hirakawa K, Ohira M. The prognostic significance of the advanced lung cancer inflammation index in patients with unresectable metastatic colorectal cancer: a retrospective study. BMC Cancer. 2019;19(1):241.

Jank BJ, Kadletz L, Schnöll J, Selzer E, Perisanidis C, Heiduschka G. Prognostic value of advanced lung cancer inflammation index in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2019; https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs00405-019-05381-0.

Shalapour S, Karin M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer: an eternal fight between good and evil. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:3347–55.

Semeniuk-Wojtaś A, Lubas A, Stec R, Syryło T, Niemczyk S, Szczylik C. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio, and C-reactive protein as new and simple prognostic factors in patients with metastatic renal cell cancer treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2018;16(3):685–93.

Li W, Luo X, Liu Z, Chen Y, Li Z. Prognostic value of C-reactive protein levels in patients with bone neoplasms: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2018;13(4):195769.

Yang X, Liu H, He M, Liu M, Zhou G, Gong P, Ma J, Wang Q, Xiong W, Ren Z, Li X, Zhang X. Prognostic value of pretreatment C-reactive protein/albumin ratio in nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a meta-analysis of published literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(30):11574.

Szor DJ, Dias AR, Pereira MA, Ramos MFKP, Zilberstein B, Cecconello I, Júnior RU. Prognostic role of neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio in resected gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2018;73:360.

Chua W, Charles KA, Baracos VE, Clarke SJ. Neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio predicts chemotherapy outcomes in patients with advanced colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2011;104(8):1288–95.

Kishi Y, Kopetz S, Chun YS, Palavecino M, Abdalla EK, Vauthey JN. Blood neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio predicts survival in patients with colorectal liver metastases treated with systemic chemotherapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16(3):614–22.

Raungkaewmanee S, Tangjitgamol S, Manusirivithaya S, Srijaipracharoen S, Thavaramara T. Platelet to lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic factor for epithelial ovarian cancer. J Gynecol Oncol. 2012;23(4):265–73.

Smith RA, Bosonnet L, Raraty M, Sutton R, Neoptolemos JP, Campbell F, Ghaneh P. Preoperative platelet-lymphocyte ratio is an independent significant prognostic marker in resected pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg. 2009;197(4):466–72.

Lu X, Guo W, Xu W, Zhang X, Shi Z, Zheng L, Zhao W. Prognostic value of the Glasgow prognostic score in colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis of 9,839 patients. Cancer Manag Res. 2018;11:229–49.

Liu Y, He X, Pan J, Chen S, Wang L. Prognostic role of Glasgow prognostic score in patients with colorectal cancer: evidence from population studies. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):6144.

Yang R, Chang Q, Meng X, Gao N, Wang W. Prognostic value of systemic immune-inflammation index in cancer: a meta-analysis. J Cancer. 2018;9(18):3295–302.

Zhong JH, Huang DH, Chen ZY. Prognostic role of systemic immune-inflammation index in solid tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2017;8(43):75381–8.

Millan DC, Watson WS, O'Gorman P, Preston T, Scott HR, McArdle CS. Albumin concentrations are primarily determined by the body cell mass and the systemic inflammatory response in cancer patients with weight loss. Nutr Cancer. 2001;39:210–3.

Don BR, Kaysen G. Serum albumin: relationship to inflammation and nutrition. Semin Dial. 2004;17(6):432–7.

Scott HR, McMillan DC, Forrest LM. The systemic inflammatory response, weight loss, performance status and survival in patients with inoperable non-small cell lung cancer. BJC. 2002;87:264–7.

Gupta D, Lis CG. Pretreatment serum albumin as a predictor of cancer survival: a systematic review of the epidemiological literature. Nutr J. 2010;9:69.

Han J, Zhou Y, Zheng Y, Wang M, Cui J, Chen P, Yu J. Positive effect of higher adult body mass index on overall survival of digestive system cancers except pancreatic cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:1049602.

Ozyurek BA, Ozdemirel TS, Ozden SB, Erdoğan Y, Ozmen O, Kaplan B, Kaplan T. Does advanced lung inflammation index (ALI) have prognostic significance in metastatic non-small cell lung cancer? Clin Respir J. 2018;12(6):2013–9.

Tomita M, Ayabe T, Nakamura K. The advanced lung cancer inflammation index is an independent prognostic factor after surgical resection in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2018;26(2):288–92.

Feng JF, Huang Y, Chen QX. A new inflammation index is useful for patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Onco Targets Ther. 2014;7:1811–185.

Vano YA, Oudard S, By MA, Têtu P, Thibault C, Aboudagga H, Scotté F, Elaidi R. Optimal cut-off for neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio: fact or fantasy? A prospective cohort study in metastatic cancer patients. PLoS One. 2018;13(4):195042.

Ikeda S, Yoshioka H, Ikeo S, Morita M, Sone N, Niwa T, Nishiyama A, Yokoyama T, Sekine A, Ogura T, Ishida T. Serum albumin level as a potential marker for deciding chemotherapy or best supportive care in elderly, advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients with poor performance status. BMC Cancer. 2017;17:797.

Greenlee H, Unger JM, LeBlanc M, Ramsey S, Hershman DL. Association between body mass index (BMI) and cancer survival in a pooled analysis of 22 clinical trials. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2017;26(1):21–9.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XH designed the study and was a major contributor in writing the manuscript; SH and JS collected the data; JC, YW, and XZ performed the statistical analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript; all authors contributed to the interpretation of the results and critically reviewed the first draft of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.

PRISMA 2009 checklist used in this meta-analysis.

Additional file 2.

Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for quality assessment.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Hua, X., Chen, J., Wu, Y. et al. Prognostic role of the advanced lung cancer inflammation index in cancer patients: a meta-analysis. World J Surg Onc 17, 177 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-019-1725-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-019-1725-2