Abstract

Objective

To determine the effect of clinical status (weight variation and performance status [PS]) at diagnosis and during induction treatment on resectability and overall survival (OS) rates in patients with borderline resectable (BRPC) or locally advanced pancreatic cancer (LAPC).

Methods

From 2005 to 2017, 454 consecutive patients were diagnosed with LAPC or BRPC. We evaluated the PS (0–1 or 2–3), body mass index at diagnosis, and weight loss (WL) > 5% at initial staging and after induction treatment and separated continuous weight loss (CWL) from weight stabilization.

Results

A total of 294 patients (64.8%) presented with WL, and 57 patients (12.6%) presented with a PS of 2–3. At restaging, 60 patients (13.2%) presented with CWL. Independent factors that poorly influenced the OS were a PS of 2–3 at diagnosis (P < .01), CWL at restaging (P < .01), and absence of resection (P < .01). Factors independently impeding resection were LAPC (P < .01), PS > 1 at diagnosis (P < .01), and CWL (P = .01). In total, 142 patients (31.3%) underwent pancreatectomy. Independent factors that poorly influenced the OS in the resected group were PS > 0 at diagnosis (P = .01) and obesity (P < .01). For the 312 unresected cancer patients (68.7%), CWL (P < .01) was identified as an independent factor that poorly influenced the OS.

Conclusion

Clinical parameters that are easy to measure and monitor are independent factors of poor prognosis. The variation of weight during the induction treatment, more than WL at diagnosis, significantly precluded resection and was an independent factor of shorter OS in unresected patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Weight loss (WL) is a cardinal sign of cancer, especially in digestive malignancies. Cachexia is commonly defined by WL > 5% within 6 months, which is sufficient enough to alter immunologic, cardiac, and respiratory functions [1]. Weight loss is observed in 50 to 80% of patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) [2,3,4], which is projected to become the second cause of cancer deaths within the next 10 years. Decreased oral intake, induced catabolism by the disease [5, 6], depression felt among the patients but also exocrine and endocrine insufficiencies are considered to be the causes of malabsorption and diabetes imbalance [7]. The biological mechanisms of the effect of WL on outcome and prognosis have not been elucidated yet [8], but have partially been explained by factors, such as the lesser doses of chemotherapy, the lesser duration of treatment, and the more side effects that these weakened patients experienced [9]. Moreover, skeletal muscle loss and adipose wasting impair functional recovery and healing and could increase postoperative complications such as postoperative pancreatic fistula, therefore prolonging hospital stay and affecting oncological outcomes [10,11,12,13]. The negative effect of WL has also been correlated with the decrease of the performance status (PS) and with quality of life [1, 14]. Locally advanced pancreatic cancer (LAPC) and borderline resectable pancreatic cancer (BRPC) are two entities of PDAC for which clinical presentation, therapeutic strategy, and prognosis are in between upfront resectable PDAC and metastatic disease. Patients usually undergo a medical treatment, for example, chemo- and/or radiotherapy, as an induction treatment and are then reevaluated by a multidisciplinary staff before being referred either to the surgeon with an “intention to resect” or to the oncologist to continue undergoing medical treatment. This long therapeutic sequence together with the tumor biology itself contributes to patients’ clinical status modifications that could strongly affect the therapeutic strategy and consequently the overall survival (OS). To date, we do not have any strong and reliable clinical or biological tool to predict which patients will benefit from his induction treatment and be selected for surgery at re-staging. As an example, weight gain during preoperative treatment has been highlighted as a strong predictor of eventual surgery [15], and we hypothesized that continuous weight loss (CWL) during the induction treatment was a sign of poor prognosis. Thus, we sought to determine the effect of clinical status (WL and PS [16]) at diagnosis and during induction treatment on resectability and OS in patients with BRPC or LAPC.

Methods

Patient selection

From January 1, 2005, to December 31, 2017, 454 consecutive patients were diagnosed as having LAPC or BRPC (according to the 2017 National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guidelines [17]) at Institut Paoli-Calmettes (Marseille, France) and consequently underwent an induction treatment. All patients’ data were entered prospectively into a clinical database approved by our Institutional Review Board. Patients eligible for the present study had a histologically proven PDAC and did not undergo up-front pancreatectomy. All patients were initially staged by physical examination (including PS and weight) and underwent thoracoabdominal computed tomography scanning (CT scan), and patients’ CA 19-9 serum levels were also measured. Due to the period of inclusion, neither liver magnetic resonance imaging nor positron emission tomography scan was routinely performed. All patients underwent an induction treatment (i.e., chemotherapy or chemoradiation) according to our period of inclusion and by multidisciplinary staff decision; endoscopy with ultrasound sonography and fine needle aspiration was performed to obtain histological confirmation prior to undergoing medical treatment.

Restaging, surgery, and adjuvant treatment

After induction treatment, patients were restaged clinically (visit with the oncologist, including the measure of weight) and by getting a new thoracoabdominal CT scan, and the multidisciplinary staff made the final decision either to continue medical treatment or to perform an explorative laparotomy with curative resection intent. Indeed, surgery exploration was decided if no disease progression had been diagnosed on the CT scan. If there was a radiological doubt on liver metastases, a hepatic MRI could be performed, but it was not done routinely in the restaging sequence. In case of surgery, a thorough abdominal exploration was first performed to rule out carcinomatosis, liver metastasis, and, more recently, para-aortic lymph node metastasis [18], precluding pancreatectomy. If appropriate, pancreatectomy with en bloc venous resection was performed as already described [19]. All specimens were inked to facilitate margin assessment. According to postoperative courses and patients’ clinical status, an adjuvant gemcitabine-based chemotherapy was performed for 6 months.

Study parameters

The variables evaluated included the following: age; gender; PS (0–1 or 2–3); body mass index (BMI) at diagnosis defining underweight (< 18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (18.5–24.9 kg/m2), overweight (25–29.9 kg/m2), and obesity ( ≥30 kg/m2); WL at diagnosis defined by a weight loss > 5% (when compared with the usual weight within the last 6 months prior to diagnosis or first disease symptoms); variation of WL between diagnosis and restaging (stabilization or increase in weight were thus opposed to CWL, defined as a decrease in weight between initial and restaging evaluation, in patients already diagnosed with WL at diagnosis), tumor location (i.e., head, body, tail); abdominal pain; jaundice; biliary stenting; type of induction treatment (i.e., chemotherapy or chemoradiation); and CA 19-9 serum level (after jaundice resolution, before induction treatment, and before surgery). In case of pancreatectomy, type of surgery (i.e., pancreaticoduodenectomy, total pancreatectomy, or distal pancreatectomy), vascular resection (venous and/or arterial), margin status (a resection margin inferior to 1.5 mm was considered as involved margin (R1) [20], lymph node status (i.e., positive or negative nodes), perineural invasion, disease staging established according to the TNM 8th classification of the American Joint Committee on Cancer [21], overall morbidity according to Clavien-Dindo Classification [22], mortality (30 and 90 days after surgery or before hospital discharge), length of hospital stay, readmission, and administered adjuvant treatment were also recorded.

Statistical analysis

Data analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software version 5.0d (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA) and SAS statistical software version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). The categorical factors were compared using Fisher’s exact test; the continuous variables were compared using the Student’s t test. The association of categorical factors with OS was assessed using the Kaplan-Meier method (based on the date of diagnosis and the date of death or status at the censored date, November 1, 2018) and was tested using the Wilcoxon test. Statistical significance was set at P value < .05. Prognostic factors with P < .1 in a univariate analysis or known to affect PDAC survival were included in a multivariable regression model to determine the independent factors.

Results

Entire cohort

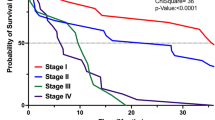

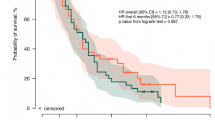

All the patients included in this retrospective study had received an induction treatment, which could be (a) chemo-radiation in 79 patients (17.4%) based on intensity-modulated fractionated radiotherapy combined with concurrent chemotherapy, with capecitabine (800 mg/m2 twice daily, 5 days/week). The total dose of radiotherapy was 45 Gy in 25 fractions/5 weeks for patients with BRPC, and this dose was increased to 54 Gy in 30 fractions/6 weeks for LAPC; (b) chemotherapy alone in 375 patients (82.6%), based on Folfirinox in 258 patients (56.8%), Gemcitabine in 89 patients (19.6%), and other regimen in 28 patients (6.2%). The mean follow-up was 22 months. The median survival time of the 454 patients was 20 months. The OS at 1, 3, and 5 years were 76%, 19%, and 10%, respectively. According to the initial staging, WL was observed in 294 patients (64.8%), and a PS of 2–3 was noted in 57 patients (12.6%). At restaging, 60 patients (13.2%) had lost weight during the induction treatment and where thus tagged as with CWL (Table 1). In a multivariate analysis (Table 2), independent factors that poorly influenced the OS were as follows: a PS of 2–3 at diagnosis (P < .01) (Fig. 1), CWL at restaging (P < .01) (Fig. 2), and absence of resection (P < .01); while they were identified as significant factors in a univariate analysis, underweight and WL were not considered significant factors in a multivariate analysis.

At restaging, 204 patients were considered as eligible to surgery and underwent laparotomy. Sixty-two could not be resected because of local extension (25 patients; 40.3%), liver metastases (13 patients; 21%), carcinomatosis (13 patients; 21%), or para-aortic lymph node metastases (11 patients; 17.7%).

Resected patients

Among the 204 patients for whom resection had been decided by the multidisciplinary staff, 142 patients (69.6%) underwent pancreatectomy after a 12-week (range, 7–44) median delay from the initiation of induction treatment. In a multivariate analysis, factors that independently impeded resection were the following: LAPC (P < .01), PS > 1 at diagnosis (P < .01), and CWL(P = .01). Only 2 patients (1.4%) with a PS of 2 at diagnosis underwent resection, whereas none of the patients with a PS of 3 at diagnosis. Seventy-four patients (52%) underwent a complete sequence of adjuvant chemotherapy (Table 3). During the follow-up period, 75 patients (52.8%) died from PDAC recurrence. The median survival time of the 142 patients was 29 months. The OS at 1, 3, and 5 years were 86%, 43%, and 31%, respectively. In a multivariate analysis (Table 4), independent factors that poorly influenced the OS were the following: PS > 0 at diagnosis (P = .01), obesity (P < .01), R1 resection (P = .04), lymph node invasion (P = .04), and absence of adjuvant treatment (P < .01).

Unresected patients

For the 312 unresected patients (68.7%), the median survival time was 17 months. The OS at 1, 3, and 5 years were 71%, 8%, and 1%, respectively. In a multivariate analysis, CWL (P < .01) was identified as an independent factor that poorly influenced the OS.

Discussion

Study highlights

In this selected population of patients with BRPC and LAPC, we found that clinical parameters that are easy to measure and monitor were independent factors of poor prognosis. Indeed, the CWL during the 3-month induction treatment period, more than WL at diagnosis, significantly precluded resection and was an independent factor of shorter OS in unresected patients. PS was an independent factor of poor prognosis in all patients, with different thresholds according to the population: the fittest patients (PS < 1) were more eligible to resection and had a better OS, whereas the more fragile patients (PS 2–3) had worse OS rates in the entire cohort analysis. PS and WL are related [23] and are routinely monitored, but are rarely used to screen the patients and indicate enhancement programs. Thus, programs of physical activity during neoadjuvant treatment have been evaluated by Parker et al. [24] in pancreatic cancer patients, as an extent to a modern enhanced recovery after surgery concept. This study revealed that patients undergoing neoadjuvant treatment for PDAC were able to follow a physical training sequence during each period of medical treatment. However, no re-nutrition program was associated, and the effect on OS was not studied. Weight stabilization has been proven to improve overall survival and quality of life in patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer [25], but no similar study has been conducted on BRPC or LAPC. Recent position paper [10] of the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery highlighted the need for considering preoperative nutritional support in order to decrease postoperative complications in patients meeting 1 out of the 4 following criteria: WL > 15% within 6 months, BMI < 18.5 kg/m2, subjective global assessment grade C or nutritional risk score > 5, and serum albumin level < 30 g/L. Here, we at the same time extend the concerned population to all LAPC and BRPC patients (before decision of surgery) and simplify the criteria to a WL > 5% and PS > 0. Setting up a multimodal prehabilitation program of renutrition and physical activity based on WL and PS at diagnosis, to improve PS and reverse the weight curve during an induction treatment, could thus be beneficial not only to LAPC and BRPC patients but also to the minority of up-front resectable patients if the recent trend of systematic induction treatment is confirmed and commonly approved. A program based on physical exercise and nutrition care could also be beneficial to the obese population, as our results revealed, consistently with the literature [26], that OS in obese patients of the resected group was worse.

Limitations

Our study has limitations: firstly, in our 454-patient cohort, the induction treatment regimen was heterogeneous, and we could not evaluate the effect of this heterogeneity on our results. Therefore, there is no clear recommendation on the optimal induction sequence, and either chemotherapy alone or chemoradiation had been administered, according to the period of inclusion which included different induction regimen at our institution. We did not focus on these differences in the induction regimen, but it would be interesting to study it separately. Secondly, this clinical study does not take into account tumor biology. It is now known that biological heterogeneity underlies PDAC development, treatment resistance, and prognosis [27]. If the epigenetic profile of a tumor seems to explain its aggressiveness, none has yet been correlated to the clinical impact for the patient. Cachexia in PDAC has been explored in fundamental studies, and mechanisms are not completely elucidated, even if some tracks are emerging, such as cytokine profiling in tumoral tissue [28]. However, the relationships between metabolism, WL, and OS in PDAC are not established [8]. Unfortunately, neither biological nor clinical factor of poor prognosis through WL or poor PS has yet been described. The origin of WL and poor PS are not even known: are they a clinical consequence of the disease or do they reflect its aggressiveness?

Conclusions and perspectives

Our results propose that continuing losing some weight during the induction treatment and bearing a poor PS are independent factors of poor prognosis in BRPC and LAPC patients, but they are dynamic criteria that have to be monitored for a few weeks. Here, we chose to look at the variation of these clinical items at reevaluation staging (after a 3-month induction treatment), but an earlier reevaluation could also be significant in order to initiate a “reconditioning” program as close to the diagnosis as possible. Yet, studies are being conducted (9 identified ongoing studies in ClinicalTrials.gov) to assess the effect of a pre-habilitation program in pancreatic cancer surgery, but these studies start when the surgery has already been planned. Thus, they do not include patients at diagnosis, whose therapeutic sequence may change due to physical and nutritional protocols. Will re-nutrition and physical rehabilitation be efficient to rectify the prognosis of the patients, or should these patients be classified in a palliative category as soon as they present a CWL and a PS > 1? To date, the answer to this question remains unknown, but recent international consensus include a PS > 2 as a clinical criteria of BRPC [29]. It is a fact that in daily clinical practice, physicians lack reconditioning propositions towards these frail patients. Clinical effects on the OS of a program aimed at improving PS and reverse weighing curve in patients with BRPC or LAPC should be assessed in a prospective study.

Availability of data and materials

All the data are available in the clinical database “CHIRPAN,” which has previously been approved by the French “Commission Nationale Informatique et Liberté.”

References

Splinter TA. Cachexia and cancer: a clinician’s view. Ann Oncol. 1992;3(Suppl 3):25–7.

Bye A, Jordhoy MS, Skjegstad G, et al. Symptoms in advanced pancreatic cancer are of importance for energy intake. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21:219–27.

La Torre M, Ziparo V, Nigri G, et al. Malnutrition and pancreatic surgery: prevalence and outcomes. J Surg Oncol. 2013;107:702–8.

Ryan DP, Grossbard ML. Pancreatic Cancer: Local success and distant failure. Oncologist. 1998;3:178–88.

Falconer JS, Fearon KC, Plester CE, et al. Cytokines, the acute-phase response, and resting energy expenditure in cachectic patients with pancreatic cancer. Ann Surg. 1994;219:325–31.

Kim SY, Wie GA, Lee WJ, et al. Changes in dietary intake, body weight, nutritional status, and metabolic rate in a pancreatic cancer patient. Clin Nutr Res. 2013;2:154–8.

Witvliet-van Nierop JE, Lochtenberg-Potjes CM, Wierdsma NJ, et al. Assessment of nutritional status, digestion and absorption, and quality of life in patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2017;2017:6193765.

Danai LV, Babic A, Rosenthal MH, et al. Altered exocrine function can drive adipose wasting in early pancreatic cancer. Nature. 2018;558:600–4.

Andreyev HJ, Norman AR, Oates J, Cunningham D. Why do patients with weight loss have a worse outcome when undergoing chemotherapy for gastrointestinal malignancies? Eur J Cancer. 1998;34:503–9.

Gianotti L, Besselink MG, Sandini M, et al. Nutritional support and therapy in pancreatic surgery: a position paper of the International Study Group on Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS). Surgery. 2018;164:1035–48.

Bozzetti F, Mariani L. Perioperative nutritional support of patients undergoing pancreatic surgery in the age of ERAS. Nutrition. 2014;30:1267–71.

Pausch T, Hartwig W, Hinz U, et al. Cachexia but not obesity worsens the postoperative outcome after pancreatoduodenectomy in pancreatic cancer. Surgery. 2012;152:S81–8.

Hendifar AE, Chang JI, Huang BZ, et al. Cachexia, and not obesity, prior to pancreatic cancer diagnosis worsens survival and is negated by chemotherapy. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2018;9:17–23.

Moningi S, Walker AJ, Hsu CC, et al. Correlation of clinical stage and performance status with quality of life in patients seen in a pancreas multidisciplinary clinic. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11:e216–21.

Sandini M, Patino M, Ferrone CR, et al. Association between changes in body composition and neoadjuvant treatment for pancreatic cancer. JAMA Surg. 2018;153:809–15.

Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, et al. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol. 1982;5:649–55.

Tempero MA, Malafa MP, Al-Hawary M, et al. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma, Version 2.2017, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017;15:1028–61.

Schwarz L, Lupinacci RM, Svrcek M, et al. Para-aortic lymph node sampling in pancreatic head adenocarcinoma. Br J Surg. 2014;101:530–8.

Turrini O, Ewald J, Barbier L, et al. Should the portal vein be routinely resected during pancreaticoduodenectomy for adenocarcinoma? Ann Surg. 2013;257:726–30.

Chang DK, Johns AL, Merrett ND, et al. Margin clearance and outcome in resected pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2855–62.

van Roessel S, Kasumova GG, Verheij J, et al. International validation of the eighth edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM staging system in patients with resected pancreatic cancer. JAMA Surg. 2018;153:e183617.

Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205–13.

Mariani L, Lo Vullo S, Bozzetti F, Group S.W. Weight loss in cancer patients: a plea for a better awareness of the issue. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20:301–9.

Parker NH, Ngo-Huang A, Lee RE, et al. Physical activity and exercise during preoperative pancreatic cancer treatment. Support Care Cancer. 2018;27(6):2275–84.

Davidson W, Ash S, Capra S, et al. Weight stabilisation is associated with improved survival duration and quality of life in unresectable pancreatic cancer. Clin Nutr. 2004;23:239–47.

Yuan C, Bao Y, Wu C, et al. Prediagnostic body mass index and pancreatic cancer survival. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:4229–34.

Lomberk G, Blum Y, Nicolle R, et al. Distinct epigenetic landscapes underlie the pathobiology of pancreatic cancer subtypes. Nat Commun. 2018;9:1978.

Gerber MH, Underwood PW, Judge SM, et al. Local and systemic cytokine profiling for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma to study cancer cachexia in an era of precision medicine. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19;(12).

Isaji S, Mizuno S, Windsor JA, et al. International consensus on definition and criteria of borderline resectable pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma 2017. Pancreatology. 2018;18:2–11.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Funding

The authors declare no funding source.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

OT contributed to the study concepts. PD and OT contributed to the study design. JG, UM, and OT contributed to the data acquisition. MG contributed to the quality control of data and algorithms. JRD and FP contributed to the data analysis and interpretation. JE contributed to the statistical analysis. PD, VW, and OT contributed to the manuscript preparation. LMZ and MG contributed to the manuscript editing. JRD contributed to the manuscript review. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This manuscript has been approved by our Institutional Review Board.

Consent for publication

All the authors gave their consent for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Duconseil, P., Garnier, J., Weets, V. et al. Effect of clinical status on survival in patients with borderline or locally advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma. World J Surg Onc 17, 95 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-019-1637-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-019-1637-1