Abstract

Background

Synovial sarcoma (SS) is a soft tissue sarcoma that rarely occurs in the spine, and a minimal number of cases have been reported in the literature. Spinal SS is challenging in diagnosis and treatment and has a poor prognosis. The aim of this study was to summarize and analyse the clinical features and outcomes of patients with spinal SS.

Methods

A total of 16 cases of patients with spinal SS admitted to our institution were reviewed retrospectively. General information, radiological findings and treatment strategies were collected. These patients were followed up regarding their continuing treatment, local or distant recurrence and survival.

Results

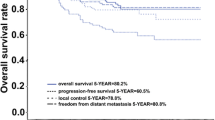

Spinal SS patients in this series ranged in age from 12 to 68 years (median, 33). Four en bloc resections and 12 piecemeal resections were performed. Improved Frankel (P = 0.002), visual analogue scale (P = 0.002) and Karnofsky Performance Status (P = 0.002) scores were seen postoperatively. The mean follow-up period was 35.9 ± 23.5 (median 31.5, range 4–87) months, with four local recurrences and three distant metastases detected. Eight patients (50.0%) died of disease by the last follow-up. The 1-, 3- and 5-year overall survival rates were 87.5%, 61.4% and 40.9%, respectively. Preoperative chemotherapy was used in three patients to facilitate surgical resection, and adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy were used in six patients.

Conclusions

Spinal SS has a relatively high risk of local recurrence and distant metastasis. Surgical intervention can improve the neurological function and relieve pain in these patients. En bloc excision is an effective treatment strategy to improve survival and prevent local recurrence. Management of spinal SS should be under the instruction of a multidisciplinary team.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Primary bone tumours of the spine are relatively rare, comprising only 10% or less of all bone tumours [1]. Synovial sarcoma (SS) is a malignancy that accounts for 6–9% of all soft tissue sarcomas (STSs) and is primarily seen in adolescents and young adults [2]. Two thirds of all SS cases are located in extremities, while less than 5% are found in the spine [3]. It can arise from the osseous and paravertebral soft tissues and even metastasize from other sites [4, 5]. With the enlargement of a SS, the mass can result in pain and other symptoms [6, 7]. Spinal instability, vertebral collapse and neurologic deficits may occur from the destruction of vertebrae structure and compression of nerve roots and the spinal cord [8, 9].

Surgical resection with negative margins is the initial treatment for SS [10]. However, sometimes a complete resection of lesions in the spine cannot be achieved due to the complex anatomical structure and the involved critical neurovascular tissue [11]. For unresectable SS, preoperative chemotherapy or radiotherapy could help downstage large, high-grade tumours and enable effective surgical resection. Adjuvant radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy are also recommended for patients with a microscopically positive margin or with high-grade histological types [12].

Due to its rarity, only a few SS cases involving the spine have been reported, most without follow-up or with a short follow-up period. Additionally, it is commonly accepted that the diagnosis and treatment of spinal SS is challenging [13, 14]. Here, we summarize the clinical features, treatments and outcomes of 16 patients with spinal SS admitted in our institution and present our experience.

Methods

Patient samples

This study was approved by the institutional review board of the Changzheng Hospital of the Second Military Medical University. We retrospectively reviewed the clinical and follow-up data of confirmed spinal SS patients who were surgically treated in our institution from August 2008 to May 2017. General information, radiological findings, pre- and post-operative status, treatment strategies, operation details, complications and pathological findings were collected. A total of 16 patients with spinal SS were identified, including 11 men and 5 women, ranging in age from 12 to 68 years (median 33). Radiologic examinations, including a plain radiograph, computed tomography (CT) scan and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), were used for preoperative diagnosis and disease evaluation. Histological diagnosis was confirmed by needle biopsy or open biopsy. Of the 16 cases, 5 occurred in the cervical spine, 4 in the thoracic spine, 3 in the lumbar spine and 4 in the sacrum.

Clinical features

The clinical presentations of all patients were collected. Features of radiologic examinations conducted before surgery were analysed. The Weinstein-Boriani-Biagnini (WBB) system was used for surgical staging [15]. Pre- and postoperative Frankel grading was carried out to assess the patient’s neurologic status. The visual analogue scale (VAS) for assessing pain and the Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) Scale were used before and 3 months after the operation. All patients were routinely followed up 1 and 3 months after the surgery and then at a 3-month interval for the first 1 year and then once every year thereafter. Patients’ conditions were all confirmed by telephone calls at the end of the study.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). The Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to compare the Frankel grades and VAS and KPS scores pre- and post-operation. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate survival. Overall survival (OS) was used as the primary end point and was defined as the interval between the first diagnosis and either death or the date of last follow-up. P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

General information

Various symptoms were recorded in these 16 spinal SS patients. Pain (15/16, 93.75%), numbness and weakness of extremities (12/16, 75.0%); limited motion of the spine (10/16, 62.5%); palpable mass (11/16, 68.75%); and disturbance of urination or defecation functions (3/16, 18.75%) were commonly observed. The mean preoperative duration of symptoms was 11.8 ± 11.8 months (median 7, range 1–42). The mean preoperative VAS and KPS scores were 5.88 ± 1.65 (median 6, range 3–9) and 45.3 ± 15.0 (median 40, range 20–70), respectively, with Frankel scores ranging from A to E (Table 1). In all 16 patients, 8 had primary lesions, while 6 had local recurrent lesions and 2 had metastatic lesions from the extremities with prior surgical treatments conducted at other institutes (Table 2).

Radiologic evaluation

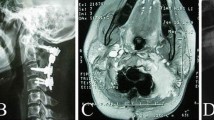

Plain radiographs showed an osteolytic lesion with a well-defined soft tissue mass in 10 out of 16 patients. Based on the preoperative radiologic imaging, the average tumour size was 7.57 ± 3.33 cm. Collapse of the vertebral body was seen in one patient with a pathological fracture of T1. CT images showed osteolytic lesions in vertebral body and/or appendix (16/16), with paravertebral or epidural soft tissue masses (12/16). Most tumours were well demarcated, and tumour calcification was found in three patients. MRI revealed heterogeneous signals in T1- and T2-weighted images of the vertebral and paravertebral lesions (Figs. 1 and 2).

Patient no. 13: MRI showing low signals in T1- (a) and heterogeneous signals in T2 (b)-weighted images of a soft tissue mass in the C7 vertebral body and appendix, with spinal cord compression from C6 to T1. CT images (c) showing a destructive soft tissue mass and osteolytic lesion in the C7 vertebral body and appendix. Cervical vertebra anterior and posterior (AP) (d) and lateral (LAT) (e) X-rays at the follow-up 52 months after surgery, demonstrating the maintenance of the instruments and spinal stability

Surgical intervention

All patients were surgically treated. The surgical approach and the instrumentation method were tailored for each patient. Four en bloc resections and 12 piecemeal resections were performed in the 16 spinal patients, with an average procedure time of 292.9 ± 121.2 (median 300, range 140–510) min and blood loss of 1547 ± 1152.8 (median 1200, range 200–4500) ml (Table 1). All resected specimens were proven with a negative margin by pathological examination. Intraoperatively, the surgical field was immersed with oxaliplatin. Spinal stability and balance were restored in accordance with the resection extension. Artificial vertebral bodies, titanium mesh cages and anterior titanium plates were applied to reconstruct the bony defects. Pedicle screw systems and lateral mass screw systems were used for posterior internal fixation (Figs. 1 and 2). A significant amelioration of Frankel scores was detected postoperatively (P = 0.002). VAS (P = 0.002) and KPS (P = 0.002) scores were also significantly improved after operation in all patients.

Adjuvant treatment

Radiotherapy and chemotherapy were used before and/or after operation based on the tumour size, surgical findings and the general status of a patient. Because of recurrent diseases and the need to facilitate surgical resection, a total of three cases received preoperative chemotherapy. Six patients had both adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Gamma knife was performed on the pulmonary metastasis of one patient.

Follow-up

The average time of follow-up for all 16 patients was 35.9 ± 23.5 (median 31.5, range 4–87) months. The 1-, 3- and 5-year OS rates were 87.5%, 61.4% and 40.9%, respectively. Four of the 16 patients (25.0%) developed local recurrence 3–10 months after surgery in our institution and one of them underwent another surgical resection. All four of these patients, three of whom had a history of recurrent disease, received piecemeal resection. Three of the 16 patients (18.75%) developed distant metastasis 8–24 months after the operation, including two lung metastases and one metastasis of the subcutaneous tissue with ulceration. Eight of the 16 patients (50.00%) died during the follow-up period, with a mean survival of 33.6 ± 26.2 (median 30.5, range 4–87) months. All eight of these patients received piecemeal resection, and the causes of death included local or distant recurrence or multiple organ failure after the operation. One (6.25%) patient was alive with the disease (AWD) at last follow-up, and the other seven (43.75%) were living without evidence of disease (NED). Postoperative complications, including wound dehiscence and fat liquefaction, were observed in one patient (Table 2).

Discussion

SS is a rare and aggressive malignancy, with a predominance in adolescents and young adults [2]. Similarly, 8 of the 16 (50.0%) patients in our study were younger than 30. This type of tumour has the potential for metastasis, with the lungs being the most susceptible site [16]. In our series, there were two patients who had a lung metastasis. One patient experienced a subcutaneous tissue metastasis, which is uncommon and has only previously been reported in prior literature twice [17]. SS occurs in the extremities, most commonly near the joints, and the rarity of spinal SS limits the sample size of studies conducted on this type of cancer [18]. Most of the available knowledge on the treatment and prognosis of spinal SS comes from sporadic cases reported in previous literature (Table 3). As far as we can tell, this is the largest conducted case series that analyses the clinical features and outcomes of these patients.

Progressive chronic pain and a palpable mass are the common symptoms of SS [2, 14, 19]. In a previous report, the duration between the onset of symptoms and start of treatment could be longer than 10 years [20]. For spinal patients, numbness or weakness of the extremities and urinary or bowel dysfunction caused by nerve root irritation or spinal cord compression are commonly seen [21,22,23]. In our series, 81.25% patients had varying degrees of neurological deficits and almost all patients had pain in tumour sites. One patient was admitted to our institution with acute lower extremity paralysis due to a compression fracture of the T1 vertebral body. His motor and sensory functions were improved significantly after surgery. Calcification seen in plain radiographs and CT scans is thought to be one of the features of SS in approximately 30% of patients [18, 24]. In our series, the calcification feature was seen in three (18.75%) patients. On MRI, most SSs have variable and heterogeneous signals in T1- or T2-weighted images [5]. Radiologic examinations are applied to detect the tumour but are difficult to use in making a diagnosis. No definitive characteristics have been seen to distinguish SS from other diseases like nerve sheath tumours, Ewing sarcoma, chondrosarcoma and other unusual STSs.

Spinal SS has a relatively poor prognosis, with a high died of disease (DOD) risk (50.00%) and a low NED (43.75%) rate, both of which are also documented in previous studies [7, 13, 16, 25]. A total of four postoperative local recurrences and three distant metastases were detected. It has been documented that most spinal SS patients die within 3 years [18], while the 5-year OS rate of all-site SS is 25–76% [7, 26]. In the current study, the 5-year OS was 40.9%, which is consistent with the published data. Sar et al. [27] reported a patient with primary SS of the sacrum who died of this disease 94 months after surgery, which is the longest survival time in literature. In our study, the longest OS was seen in a thoracic spinal SS patient, who had an 87-month survival. There are several possible reasons of the unfavourable prognosis of spinal SS. First, nerve compression can cause neurological deficits, which impacts the quality of life of these patients. Heavy blood loss and long surgical duration also affect the general status of these patients. Second, due to the complex structures of the vertebrae and surrounding tissue, sometimes en bloc excision is hard to achieve, and potential tumour residue might occur. In our study, no local recurrences were seen in the four patients who received an en bloc excision, and they seem to have a relatively good prognosis. Therefore, any tumour residue might increase the risk of postoperative recurrence. On the other hand, the special anatomic site of spinal lesions might help refine the application and dosage of radiotherapy.

Management of spinal SS should follow the instruction of a multidisciplinary team, and surgical resection serves as the first choice, if wide excision with clear margins is possible [28,29,30,31]. Subtotal resection of the tumour might be followed shortly by a local recurrence [32]. En bloc resection is important in spinal tumours to minimize the tumour residue. Kim et al. [6] reported a C2 SS removed with negative margins, and Cao et al. [33] reported another case who underwent a T7 en bloc resection. Both patients survived without recurrence in their 2- and 1-year follow-up, respectively. In our series, a total of four patients, including two with cervical lesions, one with lumbar lesions and one with sacral lesions, received en bloc resections conducted as one-stage surgeries, and they all had favourable prognoses post-surgery. None of the four patients developed local recurrence or died of this disease during the follow-up from 11 to 74 months. A two-stage surgery with the tumour removed with negative margins may also achieve satisfying local control. Puffer et al. [18] reported a case of thoracic dumbbell SS. The tumour was grossly debulked in the first stage, and en bloc resection of the T4, 5, 6 and 7 vertebrae was performed as a second-stage operation. No evidence of tumour recurrence was observed at 67 months from the final resection. For complete tumour resection, sometimes nerve roots or vessels must be sacrificed. In a case [22] of a primitive intraneural SS of the L5 nerve root, the infiltrated root was resected for complete removal of the residual lesion. A slight sensory and motor deficit in the left leg persisted during the 5-year follow-up. The decision should be made carefully, and patients should be informed, especially when cervical, lumbar and sacral nerve roots and vertebral arteries are entrapped and violated. In our series, in nine patients, including three with en bloc resection, the nerve roots were sacrificed.

Adjuvant therapies are beneficial for large, deep and high-grade STSs [28]. Six patients with an advanced tumour stage and relatively stable general status had chemotherapy and local radiotherapy following the operation. Of these six patients, one was DOD, one was AWD and four were alive with NED at their last follow-up. The relatively better outcomes for these patients might be affected by their better general condition. Most previously reported cases used adjuvant chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy [34,35,36]. Naphade et al. [37] reported a case of cervical SS where the tumour was completely excised without adjuvant treatment, and no signs of local recurrence or metastasis were detected at 6 months after surgery. There is no consensus about the role of adjuvant and preoperative chemotherapy in SS [28]. A previous study demonstrated that SS tended to have higher chemosensitivity compared to other STSs [38]. Eilber et al. [39] showed that ifosfamide-based chemotherapy offered a survival benefit to adult patients with primary extremity SS. However, Italiano et al. [12] suggested that preoperative or adjuvant chemotherapy did not improve the prognosis. Based on our study and experience, well-planned, wide surgical excision should be the cornerstone of treatment for spinal SS and the main factor indicating their prognosis. Molecular and cellular abnormalities of SS implied new therapeutic targets, and receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors like cediranib and bevacizumab have shown promising results [40,41,42].

Conclusion

We presented a case series of 16 spinal SS patients, and the features of spinal SS were roughly depicted. Spinal SS has a relatively poor prognosis. Surgical management with en bloc excision is demanding yet the most effective treatment strategy to improve outcomes. Management of spinal SS should be under the instruction of a multidisciplinary team. Therefore, a multi-centred, prospective study with a large cohort is required to further investigate the therapeutic strategy for spinal SS.

Abbreviations

- AWD:

-

Alive with the disease

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- DOD:

-

Died of disease

- KPS:

-

Karnofsky Performance Status

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- NED:

-

No evidence of disease

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- SS:

-

Synovial sarcoma

- STS:

-

Soft tissue sarcomas

- VAS:

-

Visual analogue scale

- WBB:

-

Weinstein-Boriani-Biagnini

References

Fisher CG, Keynan O, Boyd MC, Dvorak MF. The surgical management of primary tumorsof the spine: initial results of an ongoing prospective cohort study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;30:1899–908.

Kerouanton A, Jimenez I, Cellier C, Laurence V, Helfre S, Pannier S, Mary P, Freneaux P, Orbach D. Synovial sarcoma in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2014;36:257–62.

Ferrari A, De Salvo GL, Oberlin O, Casanova M, De Paoli A, Rey A, Minard V, Orbach D, Carli M, Brennan B, et al. Synovial sarcoma in children and adolescents: a critical reappraisal of staging investigations in relation to the rate of metastatic involvement at diagnosis. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:1370–5.

Koehler SM, Beasley MB, Chin CS, Wittig JC, Hecht AC, Qureshi SA. Synovial sarcoma of the thoracic spine. Spine J. 2009;9:e1–6.

Kim KW, Park SY, Won KY, Jin W, Kim SM, Park JS, Ryu KN. Synovial sarcoma of primary bone origin arising from the cervical spine. Skelet Radiol. 2013;42:303–8.

Kim J, Lee SH, Choi YL, Bae GE, Kim ES, Eoh W. Synovial sarcoma of the spine: a case involving paraspinal muscle with extensive calcification and the surgical consideration in treatment. Eur Spine J. 2014;23:27–31.

Trassard M, Le Doussal V, Hacene K, Terrier P, Ranchere D, Guillou L, Fiche M, Collin F, Vilain MO, Bertrand G, et al. Prognostic factors in localized primary synovial sarcoma: a multicenter study of 128 adult patients. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:525–34.

Ravnik J, Potrc S, Kavalar R, Ravnik M, Zakotnik B, Bunc G. Dumbbell synovial sarcoma of the thoracolumbar spine: a case report. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34:E363–6.

Morrison C, Wakely PJ, Ashman CJ, Lemley D, Theil K. Cystic synovial sarcoma. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2001;5:48–56.

Barus CE, Monsey RD, Kalof AN. Poorly differentiated synovial sarcoma of the lumbar spine in a fourteen-year-old girl. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:1471–6.

Mullah-Ali A, Ramsay JA, Bourgeois JM, Hodson I, Macdonald P, Midia M, Portwine C. Paraspinal synovial sarcoma as an unusual postradiation complication in pediatric abdominal neuroblastoma. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2008;30:553–7.

Italiano A, Penel N, Robin YM, Bui B, Le Cesne A, Piperno-Neumann S, Tubiana-Hulin M, Bompas E, Chevreau C, Isambert N, et al. Neo/adjuvant chemotherapy does not improve outcome in resected primary synovial sarcoma: a study of the French Sarcoma Group. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:425–30.

Singer S, Baldini EH, Demetri GD, Fletcher JA, Corson JM. Synovial sarcoma: prognostic significance of tumor size, margin of resection, and mitotic activity for survival. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:1201–8.

Signorini GC, Pinna G, Freschini A, Bontempini L, Dalle OG. Synovial sarcoma of the thoracic spine. A case report. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1986;11:629–31.

Chan P, Boriani S, Fourney DR, Biagini R, Dekutoski MB, Fehlings MG, Ryken TC, Gokaslan ZL, Vrionis FD, Harrop JS, et al. An assessment of the reliability of the Enneking and Weinstein-Boriani-Biagini classifications for staging of primary spinal tumors by the Spine Oncology Study Group. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34:384–91.

Ferrari A, Bisogno G, Alaggio R, Cecchetto G, Collini P, Rosolen A, Meazza C, Indolfi P, Garaventa A, De Sio L, et al. Synovial sarcoma of children and adolescents: the prognostic role of axial sites. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:1202–9.

Ryan JR, Baker LH, Benjamin RS. The natural history of metastatic synovial sarcoma: experience of the Southwest Oncology group. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1982;(164):257–60.

Puffer RC, Daniels DJ, Giannini C, Pichelmann MA, Rose PS, Clarke MJ. Synovial sarcoma of the spine: a report of three cases and review of the literature. Surg Neurol Int. 2011;2:18.

Subramanian S, Jonathan GE, Patel B, Prabhu K. Synovial sarcoma mimicking a thoracic dumbell schwannoma- a case report. Br J Neurosurg. 2018:1–4. https://doi.org/10.1080/02688697.2017.1418289.

Chambers LA, Lesher JM. Chronic thigh pain in a young adult diagnosed as synovial sarcoma: a case report. PM R. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmrj.2017.12.009. [Epub ahead of print].

Guo A, Guo F. Sudden onset of paraplegia secondary to an unusual presentation of pediatric synovial sarcoma. Childs Nerv Syst. 2016;32:2465–9.

Peia F, Gessi M, Collini P, Ferrari A, Erbetta A, Valentini LG. Pediatric primitive intraneural synovial sarcoma of L-5 nerve root. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2013;11:473–7.

Foreman SM, Stahl MJ. Biphasic synovial sarcoma in the cervical spine: case report. Chiropr Man Therap. 2011;19:12.

Garg PK, Mohnaty D, Jain BK, Goel S, Singh B. Giant subcutaneous synovial sarcoma: an interesting case. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7:3014–5.

Ferrari A, De Salvo GL, Dall'Igna P, Meazza C, De Leonardis F, Manzitti C, De Ioris MA, Casanova M, Carli M, Bisogno G. Salvage rates and prognostic factors after relapse in children and adolescents with initially localised synovial sarcoma. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:3448–55.

Spurrell EL, Fisher C, Thomas JM, Judson IR. Prognostic factors in advanced synovial sarcoma: an analysis of 104 patients treated at the Royal Marsden Hospital. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:437–44.

Sar C, Eralp L. Surgical treatment of primary tumors of the sacrum. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2002;122:148–55.

Ashford RU. Expert’s comment concerning Grand Rounds case entitled “synovial sarcoma of the spine: a case involving paraspinal muscle with extensive calcification and the surgical consideration in treatment” (by Junhyung Kim, Sun-Ho Lee, Yoon-La Choi, Go Eun Bae, Eun-Sang Kim, Whan Eoh). Eur Spine J. 2014;23:32–4.

Zairi F, Assaker R, Bouras T, Chastanet P, Reyns N. Cervical synovial sarcoma necessitating multiple neurosurgical procedures. Br J Neurosurg. 2011;25:769–71.

Arnold PM, Roh S, Ha TM, Anderson KK. Metastatic synovial sarcoma with cervical spinal cord compression treated with posterior ventral resection: case report. J Spinal Cord Med. 2010;33:80–4.

Scollato A, Buccoliero AM, Di Rita A, Gallina P, Di Lorenzo N. Intramedullary spinal cord metastasis from synovial sarcoma. Case illustration. J Neurosurg Spine. 2008;8:400.

Yang C, Fang J, Xu Y. Primary cervical intramedullary synovial sarcoma: a longitudinal observation. Spine J. 2016;16:e657–8.

Cao Y, Jiang C, Chen Z, Jiang X. A rare synovial sarcoma of the spine in the thoracic vertebral body. Eur Spine J. 2014;23(Suppl 2):228–35.

Chen Q, Shi F, Liu L, Song Y. Giant synovial sarcoma involved thoracolumbar vertebrae and paraspinal muscle. Spine J. 2016;16:e271–2.

Liu ZJ, Zhang LJ, Zhao Q, Li QW, Wang EB, Ji SJ, Shu H. Pediatric synovial sarcoma of the sacrum: a case report. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2010;19:207–10.

Yonezawa I, Saito T, Nakahara D, Won J, Wada T, Kaneko K. Synovial sarcoma of the cauda equina. J Neurosurg Spine. 2012;16:187–90.

Naphade PS, Desai MS, Shah RM, Raut AA. Synovial sarcoma of cervical intervertebral foramen: a rare cause of brachial weakness. Neurol India. 2011;59:783–5.

Karavasilis V, Seddon BM, Ashley S, Al-Muderis O, Fisher C, Judson I. Significant clinical benefit of first-line palliative chemotherapy in advanced soft-tissue sarcoma: retrospective analysis and identification of prognostic factors in 488 patients. Cancer-Am Cancer Soc. 2008;112:1585–91.

Eilber FC, Brennan MF, Eilber FR, Eckardt JJ, Grobmyer SR, Riedel E, Forscher C, Maki RG, Singer S. Chemotherapy is associated with improved survival in adult patients with primary extremity synovial sarcoma. Ann Surg. 2007;246:105–13.

Vlenterie M, Jones RL, van der Graaf WT. Synovial sarcoma diagnosis and management in the era of targeted therapies. Curr Opin Oncol. 2015;27:316–22.

Hong DS, Garrido-Laguna I, Ekmekcioglu S, Falchook GS, Naing A, Wheler JJ, Fu S, Moulder SL, Piha-Paul S, Tsimberidou AM, et al. Dual inhibition of the vascular endothelial growth factor pathway: a phase 1 trial evaluating bevacizumab and AZD2171 (cediranib) in patients with advanced solid tumors. Cancer-Am Cancer Soc. 2014;120:2164–73.

Fox E, Aplenc R, Bagatell R, Chuk MK, Dombi E, Goodspeed W, Goodwin A, Kromplewski M, Jayaprakash N, Marotti M, et al. A phase 1 trial and pharmacokinetic study of cediranib, an orally bioavailable pan-vascular endothelial growth factor receptor inhibitor, in children and adolescents with refractory solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:5174–81.

Funding

The research was generously supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81102036), the Shanghai Sailing Program (18YF1423000), and the Foundation for Young Scholars of Second Military Medical University (2017QN16, 2917QN17).

Availability of data and materials

All data analysed in our research have been presented in this published article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MY collected and analysed the clinical data and drafted the manuscript. NZ and CZ helped to analyse the data and draft the manuscript. WX conducted patient follow-up and reviewed the manuscript. SH and JZ conducted patient follow-up. XY and JX conducted patient follow-up, designed the study and reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All research was carried out in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration. This study was approved by the institutional review board of the Changzheng Hospital of the Second Military Medical University.

Consent for publication

As the images of the patients in case 13 and 14 were used in this manuscript, consent to publish has been obtained from these patients.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, M., Zhong, N., Zhao, C. et al. Surgical management and outcome of synovial sarcoma in the spine. World J Surg Onc 16, 175 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-018-1471-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-018-1471-x