Abstract

Purpose

To explore the association of academic performance and general health status with health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in school-aged children and adolescents in China.

Methods

In this cross-sectional study conducted in 2018, students (grade 4–12) were randomly chosen from primary and high schools in Nanjing, China. HRQoL, the outcome measure, was recorded using the Child Health Utility 9D, while self-rated academic performance and general health were the independent variables. Mixed-effects regression models were applied to compute mean difference (MD) and 95% confidence interval (CI) of HRQoL utility score between students with different levels of academic performance and general health.

Results

Totally, 4388 participants completed the study, with a response rate of 97.6%. The mean HRQoL utility score was 0.78 (SD: 0.17). After adjustment for socio-demographic attributes, physical activity, sedentary behavior, dietary patterns, body weight status and class-level clustering effects, students with fair (MD = 0.048, 95% CI 0.019, 0.078) and good (MD = 0.082, 95% CI 0.053, 0.112) self-rated academic performance reported higher HRQoL utility scores than those with poor academic performance, respectively. Meanwhile, students with fair (MD = 0.119, 95% CI 0.083, 0.154) and good (MD = 0.183, 95% CI 0.148, 0.218) self-assessed general health also recorded higher HRQoL utility scores than those with poor health, separately. Consistent findings were observed for participants by gender, school type and residential location.

Conclusions

Both self-rated academic performance and general health status were positively associated with HRQoL among Chinese students, and such relationships were independent of lifestyle-related behaviors and body weight status.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Health related quality of life (HRQoL) is a subjective concept frequently applied to describe people’s physical, mental, social, psychological and functional aspects of health [1, 2]. HRQoL is not only widely used for clinical purposes but also employed in public health fields [3]. It is documented that children and adolescents under the age of 18 could self-perceive the HRQoL stably in the absence of significant health/life events [4], and lifestyle and behavior factors were associated with HRQoL among children and adolescents at population level [3, 5,6,7,8,9,10]. Recently, assessment of HRQoL status for children and adolescents who are at the critical stage of growth and development has become an important topic [11]. And HRQoL has also been used to assess the public health effects of population-based lifestyle and behavior intervention programs [12, 13].

While the key task for school-aged children and adolescents is academic/curriculum learning, some students also spend a great deal of time in leisure-time physical activity (PA) but many others possess sedentary behavior (SB) and poor habits of sleeping and dietary intake. These unhealthy lifestyle-related behaviors are risk factors for some chronic conditions (e.g., obesity and cardiovascular diseases) tracking from childhood to adulthood [14, 15]. HRQoL has been found to be associated with lifestyle-related behaviors and excess body weight [3, 5,6,7,8,9,10], but little is known about its link with the academic performance/achievement and general health status among children and adolescents.

One study from Argentina reported a positive association between academic performance and HRQoL among the 4th grade students (aged 9–12 years) [16]. In this Argentina study, participants were selected from primary schools in the city of Cordoba using random cluster sampling approach in 2014, with 533 students recruited and 494 included in the analysis [16]. The HRQoL was self-reported by students with KIDSCREEN-52, while academic performance was measured with participants’ final exam scores of two subjects (written language and math) [16]. Mixed-effects regression models were applied to investigate association between academic performance and HRQoL with adjustment for students’ age, gender, socioeconomic status and mother’s educational attainment, and school-level clustering effects [16].

With respect to the relationship between general health and HRQoL among children and adolescents, except for a report from psychology freshmen in a Netherlands university documenting a positive relationship between general health and HRQoL [17], the research among school-aged children is lacking. In this Netherlands study regarding general health and HRQoL, participants (N = 118) were volunteers of psychology freshmen (mean age ± standard deviation: 21.2 ± 5.4) from the university of Amsterdam, while HRQoL was self-reported using the instrument of RAND-36 (the Dutch version of SF-36) and general health was also self-rated by students with Likert response options [17]. Correlation between general health and HRQoL was examined using Spearman correlation coefficients [17].

China not only has the largest number of students in the world, but also holds a very highly competitive academic-learning environment for school children and adolescents. Due to the high expectation of a better academic performance from the schools and parents, Chinese students ought to spend much more time in curriculum learning but less time in recreational activities than their counterparts in Western societies [18, 19]. However, no studies have previously investigated the relationship between academic performance (AP), general health (GH) and HRQoL among general school students in China. Therefore, we conducted a population-based survey among primary and high school students in 2018 in Nanjing municipality of China, aiming to examine: (1) the relationship between academic performance, general health and HRQoL; and (2) whether or not such an association was independent of lifestyle-related behaviors and body weight status.

Methods

Study design and participants

This work was part of a population-based cross-sectional study “The Built Environment and Chronic Health Conditions: Children (BEACH-Children)”, which was conducted among school-aged children and adolescents from May to June of 2018 in Nanjing municipality of China [20]. The aims of our BEACH-Children study were to investigate: (1) association of built environment characteristics with obesity and obesity-related behaviors; (2) the relationship between lifestyle-related behaviors and HRQoL; and (3) the health literacy (HL) and its influencing factors among Chinese students.

With more than 8 million registered residents within 12 administrative districts [21], Nanjing had approximately 667,000 enrolled primary and high school students in the 2017–2018 academic year [22]. On average, there were about 40 students per class in Nanjing [22]. Students from the primary (grade 4–6 only), junior (grade 7–9) and senior high schools (grade 10–12) were the participants of our BEACH-Children study.

When estimating the sample size, we attempted to warrant sufficient statistical power (90%) to simultaneously examine the three associations in our BEACH-Children study. Considering the study design, sampling approach and statistical power, using parameters from previous studies [5, 23, 24], we estimated that: (1) 3902 participants would be sufficient for investigating association between obesity and built environment attributes; (2) 2588 for identifying association between HRQoL and lifestyle-related behaviors; and (3) 1560 for examining association between HL and influencing factors. Thus, an estimated sample size of approximate 3900 was adequate for achieving primary research objectives of our BEACH-Children study.

A multi-stage random cluster sampling method was applied to choose the participants in this study. Using random digits, we randomly selected one primary, junior and senior high school from all the corresponding schools from each of the 12 districts. We then randomly chose one class from each targeting grade (4–12) from the selected schools. Consequently, 108 classes from 36 schools were included in the study and all students (N = 4498) from these selected classes were the eligible participants. The flowchart of participants’ recruitment is shown in “Appendix 1”.

Written informed consent was obtained from both the schools and parents/guardians prior to the on-site survey. Academic and Ethics Committee of Nanjing Municipal Center for Disease Control and Prevention, China, reviewed and approved this study. All personal identifications were deleted before data analysis.

Study variables

Outcome variable

The outcome variable was HRQoL, which was assessed using the validated Chinese version of Child Health Utility 9D (CHU9D-CHN) [10]. CHU9D was specifically developed to assess children/adolescents’ HRQoL for the purpose of health care treatment and public health intervention [25]. CHU9D-CHN was professionally translated from the original English version of CHU9D and cross validated for Chinese children/adolescents (age group: 9–18 years), showing good validity for measuring HRQoL among Chinese children/adolescents [10]. CHU9D comprises 9 domains, including worried, sad, pain, tired, annoyed schoolwork, sleep, daily routine, and ability to take part in activities [25]. The scoring algorithm of this instrument was also specifically developed for Chinese children and adolescents, which was reported in detail in our previous study [26]. In brief, the scoring algorithm for CHU9D was developed based on the best–worst scaling approach, and the CHU9D utility was recorded as “1” for the best state and “0” for the worst state. To investigate the association of academic performance and general health with HRQoL, we used HRQoL utility score as the continuous variable in the analysis.

Explanatory variables

Academic performance

Academic performance was self-rated by students with a question “This question asks about your overall academic performance/achievement within your class. Just a general ranking, how do you think about your present academic performance compared to your classmates?”. There were five answer options: “very good”, “good”, “fair”, “poor” or “very poor”. The original 5-point likert options were further grouped into 3 levels: “good (very good or good)”, “fair” or “poor (very poor or poor)”. In China, each student is informed of the results (grade or score) of each exam, so the student has an idea of his/her general academic performance within the class. As the overall academic performance in an academic year may more realistically reflect student’s performance than the “objectively-observed” selected subject, we then justified to use self-rated overall academic performance in our study.

General health

General health was also self-assessed by students. Each participant was asked to self-assess the present status of his/her own general health with a question “Now, think about the present status of your general health, which one of the responses below would describe it most appropriate?” [5]. This self-assessed present general health question was embedded in the CHU9D-CHN as the item 10, which has been validated among Chinese children and adolescents in our previous study [5]. Originally, this question has five ordinal response options (“very good”, “good”, “fair”, “poor”, or “very poor”) [5, 27], which was combined into 3 categories for the analysis: good (very good or good), fair, poor (“very poor or poor”).

Covariates

Students’ socio-demographic attributes, lifestyle-related behaviors and body weight status were considered as covariates. Socio-demographic attributes and lifestyle-related behaviors were self-reported by participants using standardized questionnaires. Lifestyle-related behaviors included physical activity, sedentary behavior, sleeping, and snacks and soft drinks consumption. Body weight and height were objectively measured by well-trained staff according to standard protocols.

Socio-demographic attributes

Socio-demographic attributes included participants’ age (continuous variable), sex (male or female), residential area (rural, suburban or urban), parental education (≤ 9 years, 10–12 years or 13+ schooling years) and school type (primary, junior high or senior high school).

Physical activity

Physical activity was measured with a validated instrument, the Item-specific Physical activity Scale for Chinese Children and Adolescents (I-PASCA) [28], based on participants’ self-recorded physical activity’s frequency and duration in the past 7 days. The intensity of physical activity was assessed using metabolic equivalent value (MET) according to the latest physical activity compendium: light-intensity (MET: < 3), moderate-intensity (MET: 3–6) or vigorous-intensity (MET: ≥ 6) PA [29].

Based on the weekly time of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) (moderate-PA time plus doubled vigorous-PA time), daily MVPA time was computed for each student. We defined sufficient PA as “at least 60 min/day MVPA plus ≥ 3 days/week muscle/bone-strengthening” according to the PA guidelines for Chinese children and adolescents [30]. In the present study, participants were classified as “not engaging in sufficient PA” or “engaging in sufficient PA”.

Sedentary behaviors

Screen and sleeping time were separately used to indicate sedentary behavior patterns. In the analysis, screen time was categorized into: “screen time < 2 h/day” or “screen time ≥ 2 h/day” [30], and total sleeping duration was grouped into “insufficient sleep duration” or “sufficient sleep duration” according to the recommendation for Chinese school students [31].

Dietary intake

Intake of snacks and soft drinks in the last 7 days was assessed using a validated food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) [32]. The weekly dietary consumption frequency was applied to classify participants into sub-groups for analysis. Based on the weekly median value of intake frequency for snacks (0.61 times/week) and soft drinks (1.43 times/week), snack and soft drink consumption were categorized as “lower level” or “upper level”, respectively.

Body weight status

For each participant, body weight was assessed to the nearest 0.1 kg and height to the nearest 0.01 m. Both body weight and height were measured twice and the mean value of the two readings was used to calculate body mass index (BMI). Therefore, body weight status were classified as “underweight/normal”, “overweight” or “obesity” according to the age- and gender-specific recommendations for Chinese children and adolescents [33].

Data analysis

Chi-square tests were used to examine differences in percentages for selected participants’ characteristics between school types. Due to the non-normal distribution of HRQoL utility scores, two non-parametric tests, Mann–Whitney U and Kruskal–Wallis, were used to compare the differences of HRQoL utility scores (mean, standard deviation (SD)) between subgroups of interest. Residual analysis showed that class-level cluster effects existed in this study, we thus performed mixed-effects linear regression models to compute mean difference (MD) and 95% confidence interval (CI) of HQRoL between different levels of academic performance and general health, with adjustment of age, sex, residence, physical activity, sedentary behaviors, dietary intake, school type, parents’ educational level, and class-level clustering effects. Data were double-entered and cleaned using EpiData 3.1 (The EpiData Association 2008, Odense, Denmark) and analyzed with SPSS version 20.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). P < 0.05 was set as the level of significance for two tailed test.

Results

Among all 4498 eligible participants, 4388 completed the questionnaire with a response rate of 97.6%. No difference was identified between the respondents and non-respondents in terms of age, sex and residence area. Participants recruited from the primary, junior high and senior high schools accounted for 36.5%, 33.2% and 30.3%, respectively. The mean (SD) age was 13.9 (2.5) years and 49.8% were girls. More participants resided in rural (46.3%) than the suburban (22.7%) and urban areas (31.0%). There were 16.7% overweight and 11.0% obese students (Table 1).

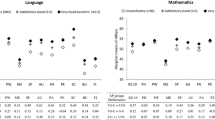

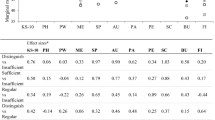

Table 2 presents HRQoL utility scores by selected socio-demographic characteristics, academic performance and general health status. The mean value of HRQoL score was 0.78 (SD: 0.17) for overall participants. A significantly positive gradient in HRQoL mean score was observed with the increasing level of academic performance (poor: fair: good = 0.73: 0.77: 0.82, ptrend < 0.001) and general health status (poor: fair: good = 0.63: 0.74: 0.82, ptrend < 0.001), respectively. Moreover, a similar pattern was consistently shown for subgroups stratified by gender, school type, and residence location (Table 3).

Table 4 displays the linear association between academic performance, general health and HRQoL scores among students after adjustment for potential confounding factors. Relative to those with poor self-rated academic performance, students with fair (MD = 0.048, 95% CI 0.019–0.078) and good self-rated (MD = 0.082, 95% CI 0.053–0.112) academic performance reported significantly higher HRQoL utility scores. Meanwhile, participants with self-assessed fair and good general health recorded an average increase of 0.119 (95% CI 0.083–0.154) and 0.183 (95% CI 0.148–0.218) unit in HRQoL score compared to those with poor self-assessed health. Similar scenarios were also observed among subgroups of gender, school type and residential location.

Discussion

In this population-based study, we attempted to examine the relationship between academic performance, general health and HRQoL among school-aged children and adolescents in China. We observed a positive association between academic performance or general health and HRQoL among Chinese school students. And, such significant associations were independent of main lifestyle-related behaviors and body weight status.

It is difficult for us to make direct comparison between our findings and those documented previously, because very few studies, like ours, were designed to investigate the relationship between academic performance, general health and HRQoL among general student population. In our study, the finding of a positive relationship between academic performance and HRQoL was consistent with that from a study among primary school students in Argentina [16]. HRQoL and academic performance were measured with different instruments between the Argentina study and ours, but all of them were self-reported by participants. Although sample sizes differed substantially (our study vs. Argentina study: 4388 vs. 494), participants were recruited following the same approach (the random cluster sampling method) and data were analyzed using the same statistical analysis method in the two studies. However, more covariates were considered in our study than those in the Argentina study.

A positive link between general health and HRQoL in our study was in line with that observed in the Netherlands university students [17]. The participants, sampling approach, sample size, instruments, and data analysis method of the Netherlands study differed from those of our study. In the Netherlands study, there were only 118 university psychology freshmen (mean age = 21.2) who voluntarily took part in the survey and the Dutch version of SF-36 was used to measure participants’ HRQoL. As for data analysis, only Spearman correlation coefficients were calculated to investigate the link between the general health and HRQoL in the Netherlands university freshmen study [17]. In our study, participants were randomly selected from primary and high schools (mean age = 13.9) with a large sample size of more than four thousands. Moreover, mixed-effects regression models were employed to examine the association of general health with HRQoL in our study.

Considering limited evidence from the literature, more studies are urgently encouraged to examine associations between academic performance, general health and HRQoL among general student populations from different societies. In the future, more well-designed studies regarding association of academic performance and general health status with HRQoL from different social, cultural and educational context are desired to provide further evidence for better understanding of potential influence of academic performance and general health on HRQoL among general students from around the world.

There were some mechanisms behind the relationship between academic performance, general health and HRQoL among students. It is consistently documented that academic performance was positively associated with life-satisfaction and happiness among children and adolescents, while poor life-satisfaction or low-level of happiness might consequently influence self-perceived HRQoL [34,35,36,37,38]. Therefore, this might partially explain the positive association between academic performance and HRQoL for children and adolescents. With respect to explanations for the association of general health and HRQoL, it was found that people with poor self-assessed general health were more likely to experience depression [39], which in turn might result in poor academic learning ability for the students [40, 41]. Thus, these might, in part, account for the positive relationship between general health and HRQoL in our study.

Some merits of this study should be mentioned. First, the instrument used to assess HRQoL in our study was CHU9D, which was the only tool specifically developed to measure HRQoL among children and adolescents. CHU9D was developed based on cost-effectiveness analysis for health-care treatment and population-based public health intervention programs [25]. Meanwhile, other instruments available for measuring HRQoL of children/adolescents were originally designed for adults and then adapted for children and adolescents [5]. Second, our study is the first one to examine the associations of academic performance and general health with HRQoL among primary and high school students in China. Third, our participants were the representative sample of overall primary and high school students within urban and rural areas in regional China. Fourth, participants’ response rate was as high as 97.6%. And, HRQoL instrument and its scoring algorithm were validated for students in China. Furthermore, findings were interesting in that each of academic performance and general health showed a positive gradient association with HRQoL among participants in this study.

However, major limitations of this study should also be addressed. First, academic performance and general health were self-reported by participants, potential bias regarding self-assessment may be a concern. Second, due to the nature of cross-sectional study, no causal relationship could be concluded between academic performance, general health and HQoL among participants.

In conclusion, this study among school-aged children and adolescents in China demonstrated that academic performance or general health status was positively associated with HRQoL, and these associations were independent of lifestyle-related behaviors and body weight status. A similar pattern was consistently observed among subgroups stratified by school type, gender or residence area. This study informs important public health implications for academic researchers and policy-makers that school-based tailored curriculum education and health promotion campaigns might improve HRQoL for students.

Availability of data and materials

Data is available upon request to corresponding authors.

References

Ravens-Sieberer U, Gosch A, Rajmil L, Erhart M, Bruil J, Duer W, Auquier P, Power M, Abel T, Czemy L, Mazur J, Czimbalmos A, Tountas Y, Hagquist C, Kilroe J, Kidscreen Group E. KIDSCREEN-52 quality-of-life measure for children and adolescents. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2005;5(3):353–64.

Naughton MJ, Shumaker SA. The case for domains of function in quality of life assessment. Qual Life Res. 2003;12(s1):73–80.

Wu XY, Han LH, Zhang JH, Luo S, Hu JW, Sun K. The influence of physical activity, sedentary behavior on health-related quality of life among the general population of children and adolescents: a systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(11):e0187668.

Palacio-Vieira JA, Villalonga-Olives E, Valderas JM, Espallargues M, Herdman M, Berra S, Alonso J, Rajmil L. Changes in health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in a population-based sample of children and adolescents after 3 years of follow-up. Qual Life Res. 2008;17(10):1207–15.

Chen G, Ratcliffe J, Olds T, Magarey A, Jones M, Leslie E. BMI, health behaviors, and quality of life in children and adolescents: a school-based study. Pediatrics. 2014;133:e868–e874874.

Gopinath B, Hardy LL, Baur LA, Burlutsky G, Mitchell P. Physical activity and sedentary behaviors and health-related quality of life in adolescents. Pediatrics. 2012;130(1):e167–e174174.

Lacy KE, Allender SE, Kremer PJ, de Silva-Sanigorski AM, Millar LM, Moodie ML, Mathews LB, Malakellis M, Swinburn BA. Screen time and physical activity behaviours are associated with health-related quality of lifein Australian adolescents. Qual Life Res. 2012;21(6):1085–99.

Wong M, Olds T, Gold L, Lycett K, Dumuid D, Muller J, Mensah FK, Burgner D, Carlin JB, Edwards B, Dwyer T, Azzopardi P, Wake M, LSAC’s Child Health CheckPoint Investigator Group. Time-use patterns and health-related quality of life in adolescents. Pediatrics. 2017;140(1):e20163656.

Xu F, Chen G, Stevens K, Zhou HR, Qi SX, Wang ZY, Hong X, Chen XP, Yang HF, Wang CC, Ratcliffe J. Measuring and valuing health-related quality of life among children and adolescents in mainland China: a pilot study. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(2):e89222.

Gopinath B, Louie JC, Flood VM, Burlutsky G, Hardy LL, Baur LA, Mitchell P. Influence of obesogenic behaviors on health-related quality of life in adolescents. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2014;23(1):121–7.

Koot HM. Challenges in child and adolescent quality of life research. Acta Paediatr. 2002;91:265–6.

Lehnert T, Sonntag D, Konnopka A, Riedel-Heller S, Konig HH. The long-term cost-effectiveness of obesity prevention interventions: systematic literature review. Obes Rev. 2012;13:537–53.

Varni J, Burwinkle T, Lane M. Health-related quality of life measurement in pediatric clinical practice: an appraisal and precept for future research and application. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2005;3:34.

World Health Organization. Global strategy on diet, physical activity and health. Childhood overweight and obesity. Reasons for children and adolescents to become obese. https://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/childhood_why/en/index.html. Accessed 28 Feb 2020.

Whitaker RC, Wright JA, Pepe MS, Seidel KD, Dietz WH. Predicting obesity in young adulthood from childhood and parental obesity. New Engl J Med. 1997;337(13):869–73.

Degoy E, Berra S. Differences in health-related quality of life by academic performance in children of the city of Cordoba-Argentina. Qual Life Res. 2018;27(6):1463–71.

Kieffer JM, Hoogstraten J. Linking oral health, general health, and quality of life. Eur J Oral Sci. 2008;116:445–50.

Yang XZ, Liu BC. Cross-sectional comparison of study burden among students in different countries. Shanghai Educ Res. 2002;4:58–61.

Zhang X, Sun H, Zhao X. Chinese children and adolescents development survey report: from those born in 1990 to 2000. China Youth Study. 2017;2:98–107.

Qin Z, Li C, Ye Q, Jin L, Ren H, Wang Z, Xu F. Neighborhood environment attributes to physical activity among children and adolescent in Nanjing, China. Chin J Public Health. https://doi.org/10.11847/zgggws1125740(in press)

Nanjing Municipal Bureau of Statistics. https://221.226.86.104/file/nj2004/2017/renkou/3-8.htm. Accessed 02 March 2018.

Nanjing Municipal Bureau of Education. https://edu.nanjing.gov.cn/zwgk/tjsjjjd/201901/t20190102_1361713.html. Accessed 02 March 2018.

Wang S, Dong Y, Wang Z, Zou Z, Ma J. Trends in overweight and obesity among Chinese children of 7–18 years old during 1985–2014. Chin J Prev Med. 2017;51(4):300–5.

Cai Z, Ni P, Bao L, Wang L, Chen T. Analysis on health literacy and its influencing factors of middle school students in Baoshan District of Shanghai. Health Educ Health Promot. 2015;10(3):179–82.

Stevens K. Developing a descriptive system for a new preference-based measure of health-related quality of life for children. Qual Life Res. 2009;18(8):1105–13.

Chen G, Xu F, Huynh E, Wang Z, Stevens K, Ratcliffe J. Scoring the Child Health Utility 9D instrument: estimation of a Chinese adolescent-specific tariff. Qual Life Res. 2019;28(1):163–76.

Ratcliffe J, Flynn T, Terlich F, Stevens K, Brazier J, Sawyer M. Developing adolescent specific health state values for economic evaluation: an application of profile case best worst scaling to the Child Health Utility-9D. Pharmacoeconomics. 2012;30:713–27.

Chu W, Wang Z, Zhou H, Xu F. The reliability and validity of a physical activity questionnaire in Chinese children. Chin J Dis Control Prev. 2014;18:1079–82.

Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Herrmann SD, Meckes N, Bassett DR Jr, Tudor-Locke C, Greer JL, Vezina J, Whitt-Glover MC, Leon AS. Compendium of physical activities: a second update of codes and MET values. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43:1575–81.

Ma Y, Ma S, Chen C, Liu S, Zhang C, Cao Z, Jiang F. Physical activity guidelines for Chinese children and adolescents. Chin J Evid Based Pediatr. 2017;12:401–8.

The State Council of China. Public bulletin on guidelines for promotion of children and adolescents’ physical activity and fitness, Beijing; 2007. p. 19. https://www.gov.cn/gongbao/content/2007/content_663655.htm. Accessed 02 March 2018.

Wang W, Cheng H, Zhao X, Zhang M, Chen F, Hou D, Mi J. Reproducibility and validity of a food frequency questionnaire developed for children and adolescents in Beijing. Chin J Child Health Care. 2016;24:8–11.

Commission of Health and Family Panning, People’s Republic of China. WS/T 586-2017 Screening for overweight and obesity among school age children and adolescents, Beijing; 2018.

Kirkcaldy B, Furnham A, Siefen G. The relationship between health efficacy, educational attainment and well-being among 30 nations. Eur Psychol. 2004;9:107–19.

Chang L, McBride-Chang C, Stewart SM, Au E. Life satisfaction, self-concept and family relations in Chinese adolescents and children. Int J Behav Dev. 2003;27:182–9.

Huebner ES, Gilman R, Laughlin JE. A multi-method investigation of the multidimensionality of children’s well-being reports: discriminant validity of life satisfaction and self-esteem. Soc Indic Res. 1999;46:1–22.

Suldo SM, Riley KN, Shaffer EJ. Academic correlates of children and adolescents’ life satisfaction. School Psychol Int. 2006;27(5):567–82.

Leung CY, McBride-Chang C, Lai BP. Relations among maternal parenting style, academic competence and life satisfaction in Chinese early adolescents. J Early Adolesc. 2004;24:113–43.

Harrington J, Perry IJ, Lutomski J, Fitzgerald AP, Shiely F, McGee H, et al. Living longer and feeling better: healthy lifestyle, self-rated health, obesity and depression in Ireland. Eur J Public Health. 2010;20:91–5.

Forrest CB, Bevans KB, Riley AW, Crespo R, Louis TA. Health and school outcomes during children’s transition into adolescence. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52(2):186–94.

Basch CE. Healthier students are better learners: a missing link in school reforms to close the achievement gap. J School Health. 2011;81(10):593–8.

Acknowledgements

Our special thanks go to all the students and their parents/guardians, school leaders, school health-care doctors and all the related teachers for kind assistance in data collection. The authors also warmly acknowledge the strong support from Nanjing Health Institute for Primary and High School in data collection. We greatly appreciate Prof. Gang Chen, Centre for Health Economics, Monash Business School of Monash University, Australia, for his kind assistance in calculating HRQoL utility scores for this study.

Funding

This work was supported by Nanjing Municipal Science and Technique Development Foundation (201715058), and a key grant from Nanjing Medical Science and Technique Development Foundation (ZKX16052).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceived, designed and directed the study: SQ, ZQ, HQ and FX. Performed the experiments: SQ, ZQ, NW and FX. Analyzed the data: SQ, ZQ and FX. Wrote the article: SQ, ZQ, NW, LAT, HQ and FX. Critical revision of the manuscript: SQ, ZQ, NW, LAT, HQ and FX. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from both schools and parents/guardians prior to the on-site survey. Academic and Ethics Committee of Nanjing Municipal Center for Disease Control and Prevention, China, reviewed and approved this study.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix 1

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Qi, S., Qin, Z., Wang, N. et al. Association of academic performance, general health with health-related quality of life in primary and high school students in China. Health Qual Life Outcomes 18, 339 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-020-01590-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-020-01590-y