Abstract

Background

Long-term lymphoma survivors often complain of persistent fatigue that remains unexplained. While largely reported in Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), long-term fatigue is poorly documented in non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHL). Data collected in two cohort studies were used to illustrate the fatigue level changes with time in the two populations.

Methods

Two cross-sectional studies were conducted in 2009–2010 (HL) and in 2015 (NHL) in survivors enrolled in European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Lymphoma Group and Lymphoma Study Association (LYSA) trials. The same protocol and questionnaires were used in both studies including the Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI) tool to assess fatigue and a checklist of health disorders. Multivariate linear regression models were used in the two populations separately to assess the influence of time since diagnosis and primary treatment, age, gender, education level, cohabitation status, obesity and health disorders on fatigue level changes. Fatigue level changes were compared to general population data.

Results

Overall, data of 2023 HL and 1619 NHL survivors with fatigue assessment available (99 and 97% of cases, respectively) were analyzed. Crude levels of fatigue were similar in the two populations. Individuals who reported health disorders (61% of HL and 64% of NHL) displayed higher levels of fatigue than those who did not (P < 0.001). HL survivors showed increasing fatigue level with age while in NHL survivors mean fatigue level remained constant until age 70 and increased beyond. HL survivors showed fatigue changes with age higher than those of the general population with health disorders while NHL survivors were in between those of the general population with and without health disorders.

Conclusions

Among lymphoma survivors progressive increase of fatigue level with time since treatment completion is a distinctive feature of HL. Our data suggest that changes in fatigue level are unlikely to only depend on treatment complications and health disorders. Investigations should be undertaken to identify which factors including biologic mechanisms could explain why a substantial proportion of survivors develop high level of fatigue.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Among disease-related symptoms cancer patients generally complain of, fatigue is probably the most frequently reported [1]. Common during treatment, fatigue usually decreases with time to normal levels within few months or years after successful treatment [2, 3]. In up to one-third of patients fatigue can persist 10 years or more but studies reporting on fatigue in long-term cancer survivors are limited [4, 5]. Most of these studies concerned individuals who survived Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), few non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHL) or both ([2, 3, 6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13], reviews in [14, 15]).

Survival improvement in HL brought physicians’ attention to persistent fatigue that was observed in a substantial proportion of survivors, including those who survived childhood HL, which might exceed 65% [2, 16]. In two series of lymphoma survivors enrolled in the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Lymphoma Group and the Lymphoma Study Association (LYSA) clinical trials, the proportions of individuals who reported long-term fatigue were 64 and 62% in HL and NHL survivors, respectively [2, 17]. Factors generally associated with increased prevalence of fatigue or increased fatigue level were age, female gender, low education level, and presence of health disorders. In contrast, persistent fatigue was unrelated to primary treatment intensity and treatment given at relapse [14].

Fatigue assessment often varies between studies (longitudinal or cross-sectional) both in time since treatment end and questionnaires used. Validated specific questionnaires mostly used were: the Fatigue Questionnaire (FQ) [18] used in 15 HL and three NHL studies; the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue (FACIT-F) [19] used in four HL studies; the Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI) [20] used in five HL and one NHL studies; and the Fatigue Assessment Scale (FAS) [21] used in three HL studies. Among validated general questionnaires that include symptoms items on fatigue, the most often used was the EORTC Quality-of-Life Core Questionnaire (QLQ-C30) [22] mentioned in 15 HL and two NHL studies.

The heterogeneity of fatigue assessment tools used, the patients’ characteristics collected including health disorders and the study designs preclude any reliable comparisons and conclusions on whether prevalence of persistent fatigue differs within survivors of lymphomas or between cancer survivors. We had the opportunity to analyze fatigue level changes in two cohorts of long-term survivors of HL and NHL based on the same study design and instruments with focus on the effect of age and follow-up.

Patients and methods

Study design

In 2009–2010 the EORTC Lymphoma Group and the LYSA have designed a cross-sectional study to collect information on socio-demographic characteristics, health situation and fatigue of HL survivors enrolled in the nine clinical trials that were conducted from 1964 to 2004. Two self-administered questionnaires were used in addition to clinical data prospectively collected and stored in a unique secured database at the EORTC Head Quarter in Brussels, Belgium. In 2015 the LYSA repeated the cross-sectional study in NHL survivors enrolled in the 12 clinical studies that were conducted from 1993 to 2010. The same two self-administered questionnaires were used in addition to clinical data prospectively collected and stored in a unique secured database at the LYSA Academic Research Organisation, Centre Hospitalier Lyon-Sud, Pierre-Bénite, France. Survivors were eligible if they had no active lymphoma, had follow-up of 5 years or more, and were free from any cancer treatments since 4 years. Detailed descriptions of the cross-sectional studies were previously published [23, 24].

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Authorizations were obtained from the EORTC Scientific and Ethical Committees, the ethical committee and legal authorities in France, and local ethical committees at each participating hospital in other European countries. The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Survivors voluntarily participated in the survey and signed informed consent.

Questionnaires and data collection

The Life Situation Questionnaire (LSQ) addresses issues not available in other validated questionnaires including: socio-demographic data, cohabitation status and highest level of education [25]; parenthood data; education, work, and insurance; health situation including height, weight, and detailed information (checklist) on post-treatment health disorders and current treatments; and social situation [23]. Self-reported health disorders that had occurred after the end of the lymphoma treatment were grouped as follows: cardiovascular, pulmonary, and musculoskeletal disorders; severe infections; anxiety; depression; and history of second cancer. No attempt was a posteriori made to confirm these diseases using data available in either medical records or computerized clinical data.

The MFI questionnaire was used to address the topic of fatigue [20]. It consisted of 20 items, each item coded 1 to 5. From the 20 items, five scales were generated: general fatigue, physical fatigue, reduced activity, reduced motivation, and mental fatigue. Each scale was constructed by summation of its four items; the total obtained was transformed to a linear score ranging from 0 to 100. Zero indicated absence of fatigue and the higher the score, the higher the level of fatigue.

Baseline patient characteristics and treatments administered were retrieved from the clinical databases. Age at survey was obtained by subtracting the date of birth to the date the questionnaires were completed. Follow-up time was obtained by subtracting the date of randomization or the date of first treatment to the date the questionnaires were completed. The weight (kg)-to-height (m2) ratio was used to calculate the body mass index (BMI) at the time of survivorship assessment; obesity was defined as a BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2.

Population study

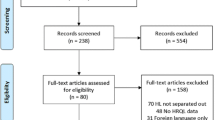

Overall, 6665 and 8113 patients were enrolled in the HL and NHL clinical studies, respectively. Of these, 5374 HL (80.6%) and 5051 NHL (62.3%) patients were alive at the time the surveys started. A postal address was obtained for 4038 HL and 3317 NHL individuals. Of these half participated in the survey giving 2032 HL (50.3%) and 1671 NHL (50.4%) cases available for analysis (Fig. 1).

Statistical analysis

Clinical characteristics, treatment protocols, and clinical outcome of NHL survivors have been recently published [17]; those of HL survivors are under submission for publication in another journal. Demographic characteristics, follow-up time since treatment initiation and medical history as reported by survivors were described using numbers and proportions for HL and NHL separately. Because incidence and initial clinical characteristics and treatment protocols differ between HL and NHL patients, no comparisons were made between the two populations. Fatigue scores at the time of survivorship assessment were first expressed using crude mean and standard deviation for the five dimensions of the MFI assessment tool for HL and NHL separately. Adjusted mean fatigue scores were also estimated using linear regression models with gender and education level, age, cohabitation status and obesity at time of survivorship assessment as covariates. The impact of self-reported health disorders on fatigue level was analyzed within each lymphoma population using adjusted t-test. Statistical tests were two-sided with statistical significance defined as a P < 0.05.

Analysis of fatigue level changes in long-term survivors of HL and NHL was performed on cases with fatigue assessment (at least one dimension score) available. Multivariate linear regression models were used to assess the influence of age and time since diagnosis and treatment as covariates on changes of the five fatigue level scores, i.e. general fatigue, physical fatigue, mental fatigue, reduced activity, and reduced motivation. Variables included in the models were age at the time of survivorship assessment, follow-up time, gender, education level, cohabitation status, obesity and presence of health disorders at fatigue assessment. Primary treatments (including autologous stem-cell transplantation administered upfront in NHL patients) were not included in the models because they did not influence long-term fatigue levels as previously shown [2, 3, 14, 17]. Salvage treatments delivered for a relapse were not considered as well for the same reason. In the results, the intercept (reference score) is the estimation of the mean fatigue score for a male aged 20 years, living with partner, with follow-up time equals zero. For age and follow-up time since treatment initiation the regression coefficient β estimates the change in score associated with a 10-year increase. Cases aged ≥70 years (10% of the population) were grouped because in a previous study focusing on NHL it was shown that fatigue level remained unchanged until 69 years of age and significantly increased beyond [17]. A score can be estimated by simply adding the following terms: intercept + (βage < 70 x (age-20)/10) + βage ≥ 70 + (βfollow-up x follow-up time/10) + βiVi (where Vi represents any covariate included in the model and βi its regression coefficient). Predicted fatigue scores were plotted according to age assuming that cases had been treated at age 45 years. No data being available in lymphoma survivors on minimal (clinical) important difference of fatigue changes based on the MFI, the regression coefficient β estimates were used to test for slopes different from zero.

An attempt was made to compare fatigue level changes with time to general population data in which fatigue level was assessed by use of the MFI instrument [26]. Data consisted of a sample of 1082 individuals (50.3% women; age range, 20 to 79) with equal size aged strata for whom socio-demographic determinants were available such as: education level, cohabitation status, and presence of self-reported health disorders (i.e. somatic or psychological disorders including cancer). Estimations of fatigue levels by age were made with adjustment on gender, education level and cohabitation status. Fatigue levels by age were plotted for individuals without and with health disorders separately. No statistical comparisons were made.

Data were analyzed at the Centre de Traitement des Données du Cancéropôle Nord-Ouest, Plateforme de Recherche Clinique Ligue Contre le Cancer, Centre François Baclesse (Caen, France). All analyses were performed with STATA software (version 14.2; STATA Corp, College Station, Texas 77,845 USA).

Results

Of the 2032 HL survivors and the 1671 NHL survivors who returned the LSQ and the fatigue assessment questionnaires, 2023 (99%) HL cases and 1619 (98%) NHL cases had fatigue assessment available and were included in the present analysis (Fig. 1). Among HL cases, 197 cases had radiation therapy alone, 345 were given chemotherapy alone, and 1447 received combined therapy as part of their primary treatment; the treatment was not specified in 34 cases. Among NHL cases (1135 with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, 461 with follicular lymphoma, and 23 with T-cell lymphoma), primary treatment consisted of conventional chemotherapy in 780 cases, intensive chemotherapy (mainly high-dose cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone [CHOP] or CHOP-like such as adriamycin, cyclophosphamide, vindesine, bleomycin, prednisone [ACVBP]) alone in 505, or combined with autologous stem cell transplantation in 334 [17]. Rituximab was administered to 807 cases.

HL and NHL characteristics

As expected, NHL cases were 15 years older than HL cases in average (Table 1). The age also explained the excess of low educated (elementary school) cases and the higher proportion of cases living without partner in NHL population. The number of health disorders reported by the participants at the time of survivorship assessment were similarly distributed in HL and NHL cases, i.e. 61.5 and 64.4%, respectively; those reporting three or more health disorders were 26.0 and 26.9%. However, NHL cases reported twice as many history of second cancer than HL cases. At the time of survivorship assessment HL and NHL cases expressed similar crude levels of fatigue than NHL cases in all dimensions. Levels of fatigue adjusted on gender, age, education level, cohabitation status and obesity were influenced by the presence of health disorders at the time the survivorship assessment was made. HL and NHL survivors reporting health disorders (any types) had significantly higher levels of fatigue than those who did not report health disorders (P < 0.001) (Table 2).

Fatigue level changes with age and follow-up time

The effects of age and time since treatment (adjusted on gender, age, education level, cohabitation status, obesity and the presence of health disorders) on the five dimensions of fatigue are shown in Table 3. In HL, mean fatigue levels significantly increased from age 20 to 69 for all dimensions except mental fatigue. In individuals aged 70 or older, age increased the mean fatigue levels for physical fatigue, reduced activity and reduced motivation only. Similarly, mean fatigue levels increased with follow-up time: a marked influence was noticed for physical fatigue; it was less important for general fatigue, reduced activity and reduced motivation. In NHL, an increase in mean fatigue levels with increased age from 20 to 69 years was observed for reduced activity. In contrast, physical fatigue level decreased with increasing age until 69 years. In older cases, the effect of age was of the same magnitude in all dimensions except mental fatigue. However, in contrast to HL, follow-up time did not influence fatigue. The combined influence of age and follow-up time on mean fatigue scores are illustrated in Fig. 2. The figures show the predicted mean fatigue scores 5 years and beyond the start of primary treatment for non-obese highly educated male survivors treated at 45 years of age, and living with partner. Main differences between HL and NHL are seen before 70 years of age with fatigue increasing in HL (Fig. 2a) and being stable or decreasing in NHL (Fig. 2b). For example, the negative effect of increasing age (β = − 1.2, Table 3) on general fatigue was more pronounced by follow-up time (β = − 1.3) ending at a slight decrease of fatigue score with increasing age in NHL. Beyond 70 years of age, the curves paralleled whatever the fatigue dimension. The same analyses were repeated on the subgroup of survivors who never relapsed of their disease, and who had a HL, a diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, or a follicular lymphoma. Of the 3642 cases, 514 (14.1%) were excluded either because they experienced a relapse (205 HL and 290 NHL), or were of T-cells histological type (n = 19). Overall, results remained unchanged.

MFI assessment: Changes of mean fatigue scores in HL (panel a) and NHL (panel b) with age. Predicted mean fatigue scores for high educated, non-obese male survivors living with partner, treated at 45 years of age. Curves start at age 50 because all survivors had at least 5 years of follow-up at the time of survivorship assessment. On the X-axis, age minus 45 equals follow-up

General population comparisons

Predicted mean fatigue scores by age were higher for both HL and NHL survivors compared with general population data [26]. Illustrations are given for low educated males living without partner for whom those who survived HL had higher fatigue levels in all dimensions than individuals who survived NHL (Fig. 3a to e). For all scale scores, HL survivors (61.5% with health disorders) displayed changes with age higher than those of the general population with health disorders; in contrast plots for NHL survivors (64.4% with health disorders) were in between those of the general population with and without health disorders except for mental fatigue (Fig. 3e).

MFI assessment: Changes of mean fatigue scores in HL, NHL, and general population with age: General fatigue (panel a), physical fatigue (panel b), reduced activity (panel c), reduced motivation (panel d), and mental fatigue (panel e). Predicted mean fatigue scores (solid lines) for Hodgkin ( ) and non-Hodgkin lymphomas (

) and non-Hodgkin lymphomas ( ) low educated males survivors, living alone, treated at 45 years of age. Predicted mean fatigue scores for general population (dash lines) with (▲) and without (▼) health disorders [17]

) low educated males survivors, living alone, treated at 45 years of age. Predicted mean fatigue scores for general population (dash lines) with (▲) and without (▼) health disorders [17]

Discussion

In the present paper, we report on fatigue changes with time in long-term survivors of lymphomas, an issue generally poorly documented concerning its quantitative aspect and particularly its relationships with health disorders. While persistent fatigue in HL survivors has brought interest of researchers since 1996 [27], the first publication focusing on NHL survivors was published in 2015 [7]. Above all, when comparisons are made between series of a given cancer localization or between cancer localizations, methodologies and instruments for fatigue assessment used often differ. In recent studies focusing on lymphomas, data from HL and NHL survivors were pooled when reporting on long-term fatigue [9,10,11,12]. We had the opportunity to develop two cross-sectional surveys with the aim to evaluate rehabilitation, health status, and long-term fatigue in survivors of lymphomas who participated in clinical protocols conducted by two European cooperative groups. In the two surveys, the same methodology and the same self-administered questionnaires were used [23, 24].

With only lymphoma survivors involved in the survey, our study shows that HL and NHL survivors display similar long-term fatigue levels in the five dimensions of the MFI assessment tool. Having or not health disorders does not change the conclusion. Changes of fatigue level can be modelled according to time since lymphoma treatment. Until age 69 years, except for mental fatigue, fatigue levels progressively increase with time in HL survivors. In NHL survivors, fatigue levels stay almost unchanged in all dimensions but two: for reduced activity a slow increase is observed; for physical activity a slow decrease is observed. Beyond 70 years of age, fatigue levels show parallel increases in both HL and NHL survivors, with HL figures always above that of NHL in all dimensions except mental fatigue.

In a cross-sectional study conducted in the general population the MFI questionnaire was used to assess the level of fatigue and a checklist was proposed to report health disorders supplemented by an open question about any other diseases [26]. In this sample, 39.7% of cases reported health disorders. Mean fatigue levels were higher (7 to 21 point difference depending of scale scores) in individuals with health disorders compared with those without health disorders. Overall, HL and NHL survivors have fatigue levels of the same magnitude than what is observed in general population cases with health disorders. HL survivors with or without self-reported health disorders always display higher levels of fatigue than general population cases with similar socio-demographic characteristics. In contrast, the figures differ in NHL survivors. Those with no self-reported health disorders have higher levels of general fatigue and reduced activity than individuals of the general population with the same characteristics. However, NHL survivors who report health disorders have levels of fatigue comparable to that of the general population with health disorders except for mental fatigue for which the levels are slightly increased. Using multiple regression analysis on general population data, age, gender, low education level, living without partner and presence of health disorders (mostly depression) significantly increased the level of fatigue with various impact according to scale scores [26]. These results were used to illustrate changes in fatigue levels according to age in HL, NHL, and general population with and without health disorders separately. The figures confirm that HL survivors suffer from long-term fatigue of similar magnitude if not higher than individuals with health disorders in the general population.

Our study confirms that a substantial proportion of long-term lymphoma survivors develop diseases that can favor the development or the persistence of fatigue. Although the numbers of individuals who complain of health disorders are rather similar among HL and NHL survivors, their types differ and we have shown that each of them have similar impact on the levels of fatigue [17, unpublished data]. Besides diseases, other individual characteristics can play a role on the development of fatigue such as a low education level, living without partner, and obesity. In contrast, the fatigue level is in almost all studies independent of treatments (primary treatment or given at relapse) as previously reported [2, 3, 14, 28]. It is also independent of NHL histological type-related treatments [7, 29].

It is unlikely that differences observed between HL and NHL survivors in changes of fatigue levels with age before 70 years can simply be explained by the presence of health disorders. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection has long been described in classical HL and, in European countries, its prevalence ranges from 31 to 40% [30]. It is associated with increased cytokine levels [31]; and genome-level mutations responsible for cytokine production induce increased fatigue level in breast cancer survivors [32, 33]. Recently, a study performed in fatigued patients with solid tumors showed that a high level of IL-1 and IL-1 Ra cytokines correlates with high levels of fatigue [34]. Variations in neurotransmitter genes have also been associated with the development of chronic fatigue in breast cancer [35]. These results suggest that fatigue could have in part a genetic origin. On the other hand, a substantial proportion of newly diagnosed patients with HL display T-lymphocytopenia that can persist long after the disease is cured suggesting chronic immunologic impairment that can relate to genetic or environmental origin [36]. NHL survivors might also suffer from immunodeficiency as indirectly suggested by a history of infections prior to diagnosis [37]. However, no genetic studies focusing on immunodeficiency and fatigue in lymphoma patients, at diagnosis or long after the treatment was completed, have been conducted so far. HL patients can also present at diagnosis with lymphocyte telomeres length shorter than that of healthy individuals [38]. Since leukocyte telomeres length reduction was shown to be associated with fatigue level in nondisabled older adults [39], one can question whether the association of multiple genetic mutations pre-existing the disease could concur to pre-treatment and/or long-term abnormal fatigue in lymphoma patients.

Conclusions

Persistent fatigue is a symptom commonly reported by cancer survivors [1] interfering with patients’ (quality of) life. Often studied in Hodgkin lymphoma, its prevalence is poorly known in non-Hodgkin lymphomas. We used self-reported fatigue data from two European cross-sectional studies conducted in long-term survivors. In both studies fatigue level was assessed and health disorders were collected using the same questionnaires. Overall, 2023 and 1619 individuals with Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphomas were available allowing comparisons of fatigue level changes with time based on multivariate linear regression modeling. At time of survivorship assessment, Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma survivors expressed similar crude mean levels of fatigue in all MFI dimensions. In both groups, fatigue levels were linked to the presence of health disorders (P < 0.001). In Hodgkin lymphoma survivors, fatigue levels increased linearly with age; in non-Hodgkin lymphoma survivors, fatigue levels remained constant until age 70 and increased afterwards parallel to what was observed in Hodgkin lymphoma. Compared to general population data, Hodgkin lymphoma survivors showed fatigue level changes with age parallel and higher than those of the general population with health disorders. In contrast, non-Hodgkin lymphoma survivors displayed fatigue level changes with age in between those of the general population with and without health disorders.

Our study is the first reporting on direct comparison between Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma survivors. It also provides indications on fatigue level changes with time with indirect comparison with general population data. No medical explanations exist for why fatigue develops or persists in some patients. In particular, long-term fatigue is unrelated to lymphoma treatments [2, 3, 14, 17]. Therefore, time has probably come to investigate its biologic origin. Conclusive results could then be used to select patients who would benefit from various tertiary prevention interventions to manage or prevent the development of persistent fatigue [40,41,42].

Availability of data and materials

R Busson, M Henry-Amar and N Mounier had full access to the data which is stored in a secured database at the Centre Hospitalo-Universitaire, Hôpital l’Archet, Nice, France (non-Hodgkin lymphoma data) and at the EORTC Head Quarter in Brussels, Belgium (Hodgkin lymphoma data). The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ACVBP:

-

Adriamycin, cyclophosphamide, vindesine, bleomycin, prednisone

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CHOP:

-

Cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone

- EBV:

-

Epstein-Barr virus

- EORTC:

-

European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer

- HL:

-

Hodgkin lymphoma

- IL-1 Ra:

-

Interleukine 1 receptor antagonist

- IL-1:

-

Interleukine 1

- LSQ:

-

Life Situation Questionnaire

- LYSA:

-

Lymphoma Study Association

- MFI-20:

-

Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory 20-item self-report instrument

- NHL:

-

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma

References

Ben Diane MK, Bouhnik AD, Foucaud J, Préau M. La fatigue. In: Institut National du Cancer, editor. La vie cinq ans après un diagnostic de cancer. Boulogne-Billancourt: INCa; 2018. p. 92–103. http://www.e-cancer.fr/Expertises-et-publications/Catalogue-des-publications/La-vie-cinq-ans-apres-un-diagnostic-de-cancer-Rapport. Accessed 20 June 2019.

Heutte N, Flechtner HH, Mounier N, Mellink WA, Meerwaldt JH, Eghbali H, et al. Quality of life after successful treatment of early-stage Hodgkin’s lymphoma: 10-year follow-up of the EORTC-GELA H8 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:1160–70.

Kreissl S, Mueller H, Goergen H, Mayer A, Brillant C, Behringer K, et al. Cancer-related fatigue in patients with and survivors of Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a longitudinal study of the German Hodgkin study group. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:1453–62.

Bower JE, Ganz PA, Desmond KA, Bernaards C, Rowland JH, Meyerowitz BE, et al. Fatigue in long-term breast carcinoma survivors: a longitudinal investigation. Cancer. 2006;106:751–8.

Servaes P, Gielissen MFM, Verhagen S, Bleijenberg G. The course of severe fatigue in disease-free breast cancer patients: a longitudinal study. Psychooncology. 2007;16:787–95.

Bower JE, Bak K, Berger A, Breitbart W, Escalante CP, Ganz PA, et al. Screening, assessment, and management of fatigue in adult survivors of cancer: an American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline adaptation. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1840–50.

Seland M, Holte H, Bjøro T, Schreiner T, Bollerslev J, Loge JH, et al. Chronic fatigue is prevalent and associated with hormonal dysfunction in long-term non-Hodgkin lymphoma survivors treated with radiotherapy to the head and neck region. Leuk Lymphoma. 2015;56:3306–14.

Ng AK, Li S, Recklitis C, Neuberg D, Chakrabarti S, Silver B, Diller L. A comparison between long-term survivors of Hodgkin's disease and their siblings on fatigue level and factors predicting for increased fatigue. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:1949–55.

Ng DL, Leong YC, Gan GG. Quality of life amongst lymphoma survivors in a developing country. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24:5015–23.

Husson O, Prins JB, Kaal SE, Oerlemans S, Stevens WB, Zebrack B, et al. Adolescent and young adult (AYA) lymphoma survivors report lower health-related quality of life compared to a normative population: results from the PROFILES registry. Acta Oncol. 2017;56:288–94.

Johannsdottir IMR, Hamre H, Fosså SD, Loge JH, Drolsum L, Lund MB, et al. Adverse health outcomes and associations with self-reported general health in childhood lymphoma survivors. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2017;6:470–6.

Bersvendsen HS, Haugnes HS, Fagerli UM, Fluge Ø, Holte H, Smeland KB, et al. Lifestyle behavior among lymphoma survivors after high-dose therapy with autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, assessed by patient-reported outcomes. Acta Oncol. 2019;58:690–9.

Bøhn SH, Thorsen L, Kiserud CE, Fosså SD, Lie HC, Loge JH, et al. Chronic fatigue and associated factors among long-term survivors of cancers in young adulthood. Acta Oncol. 2019;58:753–62.

Daniëls LA, Oerlemans S, Krol AD, van de Poll-Franse LV, Creutzberg CL. Persisting fatigue in Hodgkin lymphoma survivors: a systematic review. Ann Hematol. 2013;92:1023–32.

Linendoll N, Saunders T, Burns R, Nyce JD, Wendell KB, Evens AM, et al. Health-related quality of life in Hodgkin lymphoma: a systematic review. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2016;14:114.

Miltényi Z, Magyari F, Simon Z, Illés Á. Quality of life and fatigue in Hodgkin’s lymphoma patients. Tumori. 2010;96:594–600.

Mounier N, Anthony S, Busson R, Thiéblemont C, Nérich V, Ribrag V, et al. Long term toxicity and fatigue after treatment for non Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL): an analysis of twelve collaborative lymphoma study association (LYSA) trials, the SIMONAL study. Cancer. 2019;125:2291–9.

Chalder T, Berelowitz G, Pawlikowska T, Watts L, Wessely S, Wright D, et al. Development of a fatigue scale. J Psychosom Res. 1993;37:147–53.

Yellen SB, Cella DF, Webster K, Blendowski C, Kaplan E. Measuring fatigue and other anemia-related symptoms with the functional assessment of Cancer therapy (FACT) measurement system. J Pain Symptom Manag. 1997;13:63–74.

Smets EM, Garssen B, Bonke B, De Haes JC. The multidimensional fatigue inventory (MFI) psychometric qualities of an instrument to assess fatigue. J Psychosom Res. 1995;39:315–25.

De Vries J, Van der Steeg AF, Roukema JA. Psychometric properties of the fatigue assessment scale (FAS) in women with breast problems. Int J Clin Health Psychol. 2010;10:125–39.

Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQC30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:365–76.

van der Kaaij MAE, Heutte N, Meijnders P, Abeilard-Lemoisson E, Spina M, Moser EC, et al. Parenthood in survivors of Hodgkin lymphoma: an EORTC-GELA general population case-control study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3854–63.

Anthony S, Hebel P, Garrel A, Oliveri V, Thieblemont C, Ribrag V, et al. Conduct of epidemiologic studies in French cancer survivors: methods, difficulties encountered and solutions provided. Lessons learned from the SIMONAL study on long-term toxicities after non-Hodgkin lymphoma treatment. Bull Cancer. 2017;104:221–31.

Classifying Education Programmes. Manual for ISCED-97 Implementation in OECD Countries, 1999 ed. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD; 1999.

Watt T, Groenvold M, Bjorner JB, Noerholm V, Rasmussen NA, Bech P. Fatigue in the Danish general population. Influence of sociodemographic factors and disease. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2000;54:827–33.

Cull A, Hay C, Love SB, Mackie M, Smets E, Stewart M. What do cancer patients mean when they complain of concentration and memory problems? Br J Cancer. 1996;74:1674–9.

Hudson KE, Benecha HK, Houck KL, LeBlanc TW, Abernethy AP, Zimmerman S, et al. Fatigue in long-term non-Hodgkin lymphoma survivors. Palliative Care Oncol Symposium J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(Suppl 29S):abstract 239.

Oerlemans S, Mols F, Issa DE, Pruijt JH, Peters WG, Lybeert M, et al. A high level of fatigue among long-term survivors of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: results from the longitudinal population-based PROFILES registry in the south of the Netherlands. Haematologica. 2013;98:479–86.

Lee JH, Kim Y, Choi JW, Kim YS. Prevalence and prognostic significance of Epstein-Barr virus infection in classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a meta-analysis. Arch Med Res. 2014;45:417–31.

Chang KC, Chen PC, Chang Y, Wu YH, Chen YP, Lai CH, et al. Epstein–Barr virus latent membrane protein-1 up-regulates cytokines and correlates with older age and poorer prognosis in Hodgkin lymphoma. Histopathology. 2017;70:442–55.

Doong SH, Dhruva A, Dunn LB, West C, Paul SM, Cooper BA, et al. Associations between cytokine genes and a symptom cluster of pain, fatigue, sleep disturbance, and depression in patients prior to breast cancer surgery. Biol Res Nurs. 2015;17:237–47.

Kober KM, Smoot B, Paul SM, Cooper BA, Levine JD, Miaskowski C. Polymorphisms in cytokine genes are associated with higher levels of fatigue and lower levels of energy in women after breast cancer surgery. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2016;52:695–708.e4.

Rich T, Zhao F, Cruciani RA, Cella D, Manola J, Fisch MJ. Association of fatigue and depression with circulating levels of proinflammatory cytokines and epidermal growth factor receptor ligands: a correlative study of a placebo-controlled fatigue trial. Cancer Manag Res. 2017;9:1–10.

Eshragh J, Dhruva A, Paul SM, Cooper BA, Mastick J, Hamolsky D, et al. Associations between neurotransmitter genes and fatigue and energy levels in women after breast cancer surgery. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2017;53:67–84.e7.

Björkholm M, Holm G, Mellstedt H. Persisting lymphocyte deficiences during remission in Hodgkin’s disease. Clin Exp Immunol. 1977;28:389–93.

Anderson LA, Atman AA, McShane CM, Titmarsh GJ, Engels EA, Koshiol J. Common infection-related conditions and risk of lymphoid malignancies in older individuals. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:2796–803.

M’kacher R, Bennaceur-Griscelli A, Girinsky T, Koscielny S, Delhommeau F, Dossou J, et al. Telomere shortening and associated chromosomal instability in peripheral blood lymphocytes of patients with Hodgkin’s lymphoma prior to any treatment are predictive of second cancers. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;68:465–71.

Bendix L, Thinggaard M, Kimura M, Aviv A, Christensen K, Osler M, et al. Association of leukocyte telomere length with fatigue in nondisabled older adults. J Aging Res. 2014;2014:403253.

Oldervoll LM, Kaasa S, Knobel H, Loge JH. Exercise reduces fatigue in chronic fatigued Hodgkins disease survivors—results from a pilot study. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39:57–63.

Gielissen MF, Verhagen CA, Bleijenberg G. Cognitive behaviour therapy for fatigued cancer survivors: long-term follow-up. Br J Cancer. 2007;97:612–8.

Starreveld DEJ, Daniels LA, Valdimarsdottir HB, Redd WH, de Geus JL, Ancoli-Israel S, et al. Light therapy as a treatment of cancer-related fatigue in (non-) Hodgkin lymphoma survivors (SPARKLE trial): study protocol of a multicenter randomized controlled trial. BMC Cancer. 2018;18:880.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge Valentin Harter, MSc, for statistical advice and careful review of the text and Gilles Girault, scientific librarian at Centre François Baclesse, Caen, for his valuable help in publication retrieval. We thank the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) for permission to use data from EORTC studies H1-H9, the Lymphoma Study Association-Clinical Research (LYSA-RC) for permission to use the data from the LYSA studies, and the Nice University Hospital Centre for permission to use the data from the SIMONAL study. We are grateful to the EORTC Charitable Trust and to the Data Processing Centre, Paoli-Calmettes Institute--Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur (IPC-PACA), Marseille, for their support in collecting data. We are also grateful to all survivors who participated in the surveys.

Funding

Raphaël Busson is recipient of a fellowship from the French National League against Cancer. Michel Henry-Amar is supported by the French National League against Cancer. The Hodgkin Lymphoma survey was supported by a research grant from the Lance Armstrong Foundation and by a grant from the René Vogels Stichting. The non-Hodgkin Lymphoma survey was supported by a grant from the French drug regulatory agency (Agence Nationale de Sécurité des Médicaments [ANSM], AAP-2012-20).

One funder of the study supported the first author with a fellowship. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or reading of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RB and MHA designed the present analysis. MK, NM, HCKN, and MHA designed the study protocols. MK, BMPA, HCKN, and MHA designed the LSQ questionnaire. RB and MHA analyzed the data and wrote the first draft of the report. All authors contributed to data interpretation, reviewed the draft, and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Authorizations were obtained from the EORTC Scientific and Ethical Committees, the ethical committee and legal authorities in France, and local ethical committees at each participating hospital in other European countries. The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Survivors voluntarily participated in the survey. They gave signed personal consent.

Consent for publication

All authors have gave consent for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Busson, R., van der Kaaij, M., Mounier, N. et al. Fatigue level changes with time in long-term Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma survivors: a joint EORTC-LYSA cross-sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 17, 115 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-019-1186-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-019-1186-x