Abstract

Background

Dental care seeking behaviour is often driven by symptoms. The value of oral health related quality of life (OHRQoL) measures to predict utilisation of dental services is unknown. This study aims to explore the association between OHRQoL and problem-oriented dental attendance among adults.

Methods

We analysed cross-sectional data for 705 adults, aged 16 years and above, living in three boroughs of Inner South East London. Data were collected during structured interviews at home. The short form of the Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP-14) was used to assess the frequency of oral impacts on daily life in the last year. Problem-oriented attendance was defined based on time elapsed since last visit (last 6 months) and reason for that visit (trouble with teeth). The association between OHIP-14 (total and domain) scores and problem-oriented attendance was tested in logistic regression models adjusting for participants’ sociodemographic characteristics.

Results

Problem-oriented attenders had a higher OHIP-14 total score than regular attenders (6.73 and 3.73, respectively). In regression models, there was a positive association between OHIP-14 total score and problem-oriented attendance. The odds of visiting the dentist for trouble with teeth were 1.07 greater (95% Confidence Interval: 1.04–1.10) per unit increase in the OHIP-14 total score, after adjustment for participants’ sociodemographic characteristics. In subsequent analysis by OHIP-14 domains, greater scores in all domains but handicap were significantly associated with problem-oriented attendance.

Conclusion

This study shows that oral impacts on quality of life are associated with recent problem-oriented dental attendance among London adults. Six of the seven domains in the OHIP-14 questionnaire were also associated with dental visits for trouble with teeth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

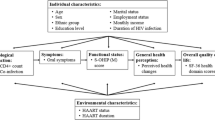

Dental care-seeking behaviour is mainly motivated by symptoms [1, 2]. The Behavioural Model of Health Services Use [3, 4] has been used to understand how contextual- and individual-level characteristics influence health services utilisation, including dental services use [5,6,7]. According to the model, individuals will seek health care only when they perceive a need for treatment [3, 4]. People’s perception of their oral health status and the related oral impacts on daily life are important in planning services designed to improve their quality of life [8]. From this point of view, oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL) measures might be useful for the identification of people with the greatest need and priority for care. However, not everybody having oral impacts on daily activities may demand dental care. Therefore, the potential of OHRQoL measures to predict the use of dental services is still unknown.

Earlier studies on the relationship between OHRQoL and dental services utilisation were conducted in children [9,10,11]. While two of those studies showed the impact of oral conditions on children’s quality of life was positively associated with recent visits to the dentist [9, 10], the remaining study reported no association between the child’s quality of life and utilisation of dental services [11]. What is more, the authors also showed that oral impacts on the family (parental distress and family function) were associated with lower utilisation of dental services [11]. The few studies in adults also showed conflicting results. A study among older adults in Sendai (Japan) reported no significant association between impaired OHRQoL, as measured by the Oral Impacts on Daily Performances (OIDP) instrument, and dental services use within the past year in crude or adjusted regression models [12]. A study among Canadian adults showed that having difficulties in chewing and sleep due to oral conditions were significantly associated with problem-oriented visits to the dentist among the working poor (i.e., working people with incomes below a certain poverty threshold). These associations were attenuated after controlling for participants’ socio-demographic characteristics. In addition, the presence of pain/discomfort, feelings of embarrassment and difficulty in working due to oral conditions were not significantly associated with problem-oriented attendance [13]. Lastly, a cross-sectional study among 344 underprivileged older people living in Jerusalem (Israel) showed no significant association between the short form of the Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP-14) and dental visiting in the last 6 months after adjustments for socio-demographic factors [14]. Further research using population-based samples, as opposed to specific population sub-groups (such as the working poor or older adults) and carried out in alternative settings is needed to shed some lights on the hypothesised association. Such information would support the use of OHRQoL measures for planning dental services and predicting utilisation. A study was set out to determine the association between OHRQoL and problem-oriented dental attendance among adults. It was hypothesised that adults who experienced oral impacts on daily life were more likely to visit the dentist for trouble with teeth than those who did not experience such impacts.

Methods

Data source

A population-based oral health survey was carried out in Inner South East London to identify perceived dental needed and dental care seeking behaviour of adults in Inner South East London. King’s College London Research Ethics Committee approved the survey protocol. A representative, multi-ethnic sample of the general population aged 16 years and above living in Lambeth, Southwark and Lewisham (approx. 580,000 inhabitants) was recruited using stratified multistage random sampling. A list of all valid addresses for postal delivery in each borough (stratum) organised by postcode sectors (primary sampling units) was the sampling frame. Addresses were selected in two stages. Fifteen postcode sectors were first selected from each borough randomly and a sample of addresses was subsequently selected from each sector randomly. Household rosters were generated in every eligible household, from which only one adult was invited to participate. A target of 500 addresses per borough was initially set out (1500 overall, sampling fraction: 0.003). Of them, 1244 were valid and 770 (62% response rate) agreed to take part in the survey [15]. Based on the valid addresses, no contact was possible with 25% of households (after 4 calls were made to the address) and a further 13% of households refused to participate in the survey.

For the present analysis, 65 participants were excluded because of missing values on ethnicity (n = 32), OHRQoL (n = 22) and social grade (n = 14). Our study sample included 695 adults (56% of the eligible sample). A power calculation showed that our analytical sample had 90% power to detect a difference in the OHIP-14 total score of 2 units or greater between regular and problem-oriented attenders (using a 5 to 1 ratio), at 5% significance level and assuming a common standard deviation of 6 units.

Data collection

Data were collected through structured interviews at home. All fieldwork was carried out by 12 experienced and trained interviewers. The interviewer made arrangements to return at a later date with a translator if needed. The survey instrument gathered information on sociodemographic characteristics (sex, age and ethnicity), dental care seeking behaviour and perceived dental needs, all based on previous national surveys [16,17,18]. Participants ethnicity was self-assigned as White, Asian, Black, Mixed and Other [18]. Participants’ socioeconomic status was determined by the social grade of the chief income earner (CIE) in the household. Information on the CIE current job or occupation, employment status, size of organization and supervisory status were used to classify them as: high managerial, administrative, or professional (A); intermediate managerial, administrative, or professional (B); supervisory, clerical, and junior managerial, administrative, or professional (C1); skilled manual workers (C2); semi- and unskilled manual workers (D); and state pensioners, casual, or lowest-grade workers, or unemployed with state benefits only (E) [19]. For analysis, three groups were generated by merging grades A and B (highest group), C1 and C2 (intermediate), and D and E (lowest) [15, 20].

Participants’ OHRQoL was assessed with the short form of the Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP-14) [21], which measures the frequency of oral impacts on everyday life within the past year. Questionnaire items are organised in 7 domains: functional limitation, physical pain, psychological discomfort, physical disability, psychological disability, social disability and handicap. Responses were provided using 5-point ordinal scales (never = 0, hardly ever = 1, occasionally = 2, fairly often = 3 and very often = 4). Domain scores were calculated by adding the responses to the two corresponding items (range: 0 to 8) and the total score by adding the responses to all 14 items (range: 0 to 56). Higher scores indicated worse OHRQoL [22, 23]. Participants with missing values in one or more OHIP-14 items were excluded [24, 25].

Participants also reported the time since last dental visit (≤6 months, between 7 and 12 months, between 13 and 24 months, over 2 years ago and never been) and the reason for that visit (trouble with teeth, check-up and other reasons). Based on the answers to both questions, recent problem-oriented attendance was defined as having visited the dentist in the past 6 months for trouble with teeth. The 6-month threshold was selected to mimic a temporal ordering between exposure (oral impacts) and outcome (dental attendance) and identify dental services use that most likely occurred after the experience of oral impacts [10].

Statistical analysis

All analyses were weighted to correct for differences in the probability of selection because of non-response and non-coverage, and to adjust for differences in the age-by-sex-by-ethnicity distribution between the sample and the general adult population 16 years or older in the three London boroughs included in the study, according to the 2001 UK Census [15, 20].

We first present the characteristics of the sample and compare them against those excluded due to missing values with the Chi-square test to evaluate the impact of missing data. We then compared the proportion of problem-oriented attenders by sociodemographic characteristics with the Chi-square test. OHIP-14 total and domain scores were compared between problem-oriented and regular attenders using the t-test. The association between OHIP-14 total score and recent problem-oriented attendance was assessed in crude and adjusted logistic regression models. The adjusted model controlled for sex, age groups, ethnicity, borough of residence and social grade. A similar set of models was used when testing the association between each OHIP-14 domain score and problem-oriented attendance. Multilevel modelling (participants nested within boroughs) was not considered due to the limited number of clusters. Instead, we included borough of residence as an explanatory variable in regression models as it is often done for geographical variables with few groupings such as rural/urban status.

Results

The study sample consisted of 705 adults (51% women) residing in Inner South East London. Table 1 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of the study sample. There were no significant differences in sociodemographic composition, OHIP-14 scores and dental attendance pattern between the study sample and those excluded because of missing data on relevant variables. The proportion of problem-oriented attenders was 15.4%, with no differences by sociodemographic factors.

The mean OHIP-14 score was 4.19 (SD: 6.06; range: 0 to 50), with the highest score for physical pain (mean: 1.50, SD: 1.66) and the lowest score for social disability (mean: 0.22 SD: 0.77). Problem-oriented attenders had a significantly higher OHIP-14 total score than regular attenders (6.73 versus 3.73). Problem-oriented attenders also had significantly higher OHIP-14 scores than regular attenders in all domains except for handicap (Table 2). The largest differences were found in physical pain (2.18 versus 1.38) and physical disability (0.86 versus 0.27), whereas the smallest (although significant) difference was found in psychological disability (0.79 versus 0.53).

There was a positive association between OHIP-14 total score and problem-oriented attendance (Table 3). The odds of visiting the dentist when having trouble with teeth were 1.07 greater (95% Confidence Interval: 1.04–1.10) per unit increase in the OHIP-14 total score, after adjustment for participants’ sociodemographic characteristics. In subsequent analysis by OHIP-14 domains, greater scores were significantly associated with problem-oriented attendance except for handicap. The adjusted odds of visiting the dentist when having trouble with teeth were 1.35 (95%CI: 1.12–1.61), 1.31 (95%CI: 1.16–1.47), 1.24 (95%CI: 1.09–1.40), 1.68 (95%CI: 1.39–2.04), 1.19 (95%CI: 1.01–1.39) and 1.38 (95%CI: 1.13–1.68) times greater per unit increase in the scores for functional limitation, physical pain, psychological discomfort, physical disability, psychological disability and social disability, respectively (Table 4).

Discussion

This study shows that adults with poorer oral health related quality of life in the past year were more likely to have a recent visit to the dentist for trouble with their teeth. In addition, greater scores in all OHIP-14 domains in OHIP-14, except for handicap, were significantly associated with problem-oriented attendance. These associations were robust to adjustments for participants’ sociodemographic characteristics.

Some study limitations need to be considered. First, analyses were based on cross-sectional data and thus restricted to identify associations between the variables of interest rather than causal relationships. This is a relevant issue as it is not possible not know if oral impacts led to dental services use or vice-versa. However, we attempted to minimise this issue by using a longer recall period for oral impacts than for dental services utilisation (12 and 6 months, respectively). Second, the study sample represented 56% of the eligible sample, which some may view as non-representative. However, we used analytical weights to correct for key demographic differences between the study sample and the local population living in Inner South East London, thus allowing for the generalisation of findings to the study population. That said, the present findings are not generalizable beyond the study population (external validity). Third, participants’ utilisation of dental services was obtained through self-reports, which could be affected by information bias. However, self-reported dental visits have shown high levels of agreement with data from dental records [26, 27]. Fourth, we could not adjust for clinical measures of oral health (dental caries, periodontal disease, number of teeth) because these data were not collected in the survey. Clinical oral health may confound the association between OHRQoL and dental services utilisation. We attempted to minimise this effect by controlling for more distal determinants of oral health, such as social grade and ethnicity, because poor oral health is overrepresented among ethnic minorities [28, 29] and lower socioeconomic groups [30].

Going back to our findings, the magnitude of the association between oral impacts on quality of life and problem-oriented attendance was such that the odds of visiting the dentist for trouble with teeth increased by 7% per every unit increase in the OHIP-14 total score. There was a clear dose-response relationship, with greater odds of using dental services at higher OHIP-14 scores. Our finding disagrees with the only previous study that used the OHIP-14 to measure OHRQoL [14]. This difference could be explained by the sample composition (underprivileged older adults with similar levels of oral impacts), the definition of dental attendance used (any visit to a specific hospital in the last 6 months) and the higher levels of oral impacts on quality of life (mean OHIP-14 score: 10.43) found in the previous study.

Six of the seven domains in Locker’s model of consequences of oral health [31], spanning from functional limitation to physical pain to discomfort to disability (physical, psychological and social disability), were positively associated with problem-oriented attendance. Interestingly, it was not physical pain but physical disability the domain most strongly associated with problem-oriented attendance. Difficulty in eating among children [10] and difficulty in chewing among adults (although not significantly in multivariable regression models) [13] have been previously reported as stronger indicators of utilisation of dental services. The two items in the physical disability domain were ‘have you had to interrupt meals’ and ‘has your diet been unsatisfactory because of problems with your teeth, mouth or dentures’. Given the fact that the item ‘have you found it uncomfortable to eat any foods’ was included in the physical pain domain, the current findings suggest that it is the enjoyment of food rather than merely chewing which may trigger a dental visit. On the other hand, handicap was the only domain not significantly associated with problem-oriented attendance. This finding may be explained by the broader items included in this domain (‘have you felt that life in general was less satisfying’ and ‘have you been totally unable to function’), which did not emphasise on specific signs and symptoms related to dental problems. The lower frequency of oral impacts at handicap level may also explain the negative findings. Indeed, fewer impacts on the handicap domain of the OHIP-14 have been reported in the last two Adult Dental Health Surveys in the UK [32, 33].

There are some implications for policy and research. There might be some benefit in using OHRQoL measures for planning and predicting utilisation of dental services. In this regard, the socio-dental approach is a way forward in the complementary use of clinical and perceived measures for needs assessment, planning and prioritisation of services [34, 35]. Information on the association between OHRQoL measures and use of dental services is scarce. Further research is thus needed, using longitudinal data, from alternative settings and assessing not only the frequency but also the severity of oral impacts in relation to accessing dental services in order to understand if oral impacts on quality of life could predict dental services utilisation. It would also be interesting to know whether normative or perceived need (of which OHRQoL are only an indicator) is the strongest predictor of utilisation of dental services.

Conclusions

This study shows that oral impacts on quality of life in the last year are associated with recent problem-oriented dental attendance among adults in Inner South East London. Six of the seven domains in the OHIP-14 questionnaire were also associated with dental visits for trouble with teeth.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- OHIP:

-

Oral Health Impact Profile

- OHRQoL:

-

Oral health-related quality of life

- OIDP:

-

Oral Impacts on Daily Performances

- OR:

-

Odds ratios

- SD:

-

Standard Deviation

- UK:

-

United Kingdom

References

Gilbert GH, Duncan RP, Vogel WB. Determinants of dental care use in dentate adults: six-monthly use during a 24-month period in the Florida Dental Care Study. Soc Sci Med. 1998;47:727–37.

Duncan RP, Gilbert GH, Peek CW, Heft MW. The dynamics of toothache pain and dental services utilization: 24-month incidence. J Public Health Dent. 2003;63:227–34.

Andersen RM. National health surveys and the behavioral model of health services use. Med Care. 2008;46:647–53.

Andersen RM, Rice TH, Kominski GF, Afifi AA, Rosenstock L. Changing the U.S. Health Care System: Key Issues in Health Services Policy and Management. Wiley. 2007.

Marshman Z, Porritt J, Dyer T, Wyborn C, Godson J, Baker S. What influences the use of dental services by adults in the UK? Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2012;40:306–14.

Astrom AN, Ekback G, Nasir E, Ordell S, Unell L. Use of dental services throughout middle and early old ages: a prospective cohort study. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2013;41:30–9.

Bhandari B, Newton JT, Bernabe E. Income Inequality and Use of Dental Services in 66 Countries. J Dent Res. 2015;94:1048–54.

Cavalheiro CH, Abegg C, Fontanive VN, Davoglio RS. Dental pain, use of dental services and oral health-related quality of life in southern Brazil. Braz Oral Res. 2016;30:1.

Goettems ML, Ardenghi TM, Demarco FF, Romano AR, Torriani DD. Children’s use of dental services: influence of maternal dental anxiety, attendance pattern, and perception of children’s quality of life. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2012;40:451–8.

Monsantofils M, Bernabe E. Oral impacts on daily performances and recent use of dental services in schoolchildren. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2014;24:417–23.

Granville-Garcia AF, Clementino MA, Gomes MC, Costa EM, Pinto-Sarmento TC, Paiva SM. Influence of Oral Problems and Biopsychosocial Factors on the Utilization of Dental Services by Preschool Children. J Dent Child (Chic). 2015;82:76–83.

Ohi T, Sai M, Kikuchi M, Hattori Y, Tsuboi A, Hozawa A, Ohmori-Matsuda K, Tsuji I, Watanabe M. Determinants of the utilization of dental services in a community-dwelling elderly Japanese population. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2009;218:241–9.

Muirhead VE, Quinonez C, Figueiredo R, Locker D. Predictors of dental care utilization among working poor Canadians. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2009;37:199–208.

Zini A, Vered Y, Sgan-Cohen HD. The association between demographic and oral health-related quality of life factors and dental care attendance among underprivileged older people. Australas J Ageing. 2011;30:70–6.

Al-Haboubi M, Klass C, Jones K, Bernabe E, Gallagher JE. Inequalities in the use of dental services among adults in inner South East London. Eur J Oral Sci. 2013;121:176–81.

Kelly M, Steele J, Nuttall N, Bradnock G, Morris J, Nunn J, Pine C, Pitts N, Treasure E, White D. Adult Dental Health Survey: Oral Health in the United Kingdom 1998. London: The Stationary Office; 2000.

National Readership Survey. London: Publishers Audience Measurement Company Ltd (PAMCo Ltd); 2008.

Ethnic group statistics: A guide for the collection and classification of ethnicity data [http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20160105160709/http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/guide-method/measuring-equality/equality/measuring-equality--a-guide/ethnic-group-statistics--a-guide-for-the-collection-and-classification-of-ethnicity-data.pdf]. Accessed 15 Jan 2017.

Market and Opinion Research International. Social grade: A classification tool - Bite sized thought piece. London: Ipsos MediaCT - The Media, Content and Technology Research Specialists; 2009.

Abdelrahim R, Delgado-Angulo EK, Gallagher JE, Bernabé E: Ethnic Disparities in Perceived Oral Health among Adults in London, England. Community Dent Health. 2017, (in press).

Slade GD. Derivation and validation of a short-form oral health impact profile. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1997;25:284–90.

Slade GD, Spencer AJ, Locker D, Hunt RJ, Strauss RP, Beck JD. Variations in the social impact of oral conditions among older adults in South Australia, Ontario, and North Carolina. J Dent Res. 1996;75:1439–50.

Slade GD, Nuttall N, Sanders AE, Steele JG, Allen PF, Lahti S. Impacts of oral disorders in the United Kingdom and Australia. Br Dent J. 2005;198:489–93. discussion 483.

Bernabe E, Marcenes W. Periodontal disease and quality of life in British adults. J Clin Periodontol. 2010;37:968–72.

Li MH, Bernabe E. Tooth wear and quality of life among adults in the United Kingdom. J Dent. 2016;55:48–53.

Gilbert GH, Rose JS, Shelton BJ. A prospective study of the validity of data on self-reported dental visits. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2002;30:352–62.

Gilbert GH, Rose JS, Shelton BJ. A prospective study of the validity of self-reported use of specific types of dental services. Public Health Rep. 2003;118:18–26.

Delgado-Angulo EK, Bernabe E, Marcenes W. Ethnic inequalities in periodontal disease among British adults. J Clin Periodontol. 2016;43:926–33.

Delgado-Angulo EK, Bernabe E, Marcenes W. Ethnic inequalities in dental caries among adults in East London. J Public Health (Oxf). 2016;38:e55–62.

White D, Pitts NB, Steele J, Sadler K, Chadwic B. Disease and related disorders - a report from the Adult Dental Health Survey 2009. London: The Health and Social Care Information Centre; 2011.

Locker D. Measuring oral health: a conceptual framework. Community Dent Health. 1988;5:3–18.

Nuttall NM, Steele JG, Pine CM, White D, Pitts NB. The impact of oral health on people in the UK in 1998. Br Dent J. 2001;190:121–6.

White DA, Tsakos G, Pitts NB, Fuller E, Douglas GV, Murray JJ, Steele JG. Adult Dental Health Survey 2009: common oral health conditions and their impact on the population. Br Dent J. 2012;213:567–72.

Gherunpong S, Sheiham A, Tsakos G. A sociodental approach to assessing children’s oral health needs: integrating an oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL) measure into oral health service planning. Bull World Health Organ. 2006;84:36–42.

Bernabe E, de Oliveira CM, Sheiham A. Comparison of the discriminative ability of a generic and a condition-specific OHRQoL measure in adolescents with and without normative need for orthodontic treatment. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2008;6:64.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding

The authors are indebted to Lambeth, Southwark, and Lewisham PCTs for their support and funding for this project, Ipsos MORI for undertaking the fieldwork, and local residents for participating in the survey.

Availability of data and material

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors’ contributions

EB conceived of the study. PG analysed the data and drafted the first version of the manuscript. JEG supervised data collection. EKDA supervised data analysis and interpretation of findings. All authors revised the manuscript critically and approved the final version submitted for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was based on secondary data analysis and did not require ethics approval.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Gaewkhiew, P., Bernabé, E., Gallagher, J.E. et al. Oral impacts on quality of life and problem-oriented attendance among South East London adults. Health Qual Life Outcomes 15, 82 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-017-0663-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-017-0663-3