Abstract

Background

The utility of ezetimibe in preventing cardiovascular outcomes remains controversial. To guide future assessments of the effectiveness of ezetimibe in routine care, we evaluated how this medication has been prescribed to high-risk older adults in Ontario, Canada.

Methods

Using linked healthcare databases, we carried out a population-based cohort study of older adults who were discharged from hospital following an acute myocardial infarction from 2005 until 2014. We ascertained the rate of ezetimibe initiation within 6 months of their discharge. We also examined the characteristics of new ezetimibe prescriptions, as well as the predictors for receiving the therapy.

Results

Seventy one thousand one hundred twenty five older adults were hospitalized for an acute myocardial infarction between 2005 and 2014 (mean age 78.36 ± 7.71 years, 45.8% women). Only 1230 (1.7%) patients were newly prescribed ezetimibe within 6 months of their hospital discharge. The median duration of continuous use of ezetimibe was 1.2 years (IQR 0.3–3.5 years). Ezetimibe was prescribed more often to patients living in rural areas, with a history of coronary artery disease, on high-potency statins, and, with evidence of healthcare follow-up after hospital discharge. Prescriptions were less common in men, older patients, those living in long-term care facilities, those with a history of congestive heart failure, and those who were hospitalized for a myocardial infarction in more recent years.

Conclusions

Real-world drug effectiveness studies can help to complement the findings of randomized controlled trials. In our region however, only a small proportion of high-risk older adults received a prescription for ezetimibe following a myocardial infarction. Clinical and research implications are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Given their proven efficacy in lowering low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and reducing cardiovascular events and mortality, statins are first-line therapy for the treatment of dyslipidemia [1]. Despite their efficacy however, some patients experience side effects from statins [2], and are unable to attain their lipid targets [3,4,5,6]. Although recent clinical trial evidence supports the selective use of non-statin agents for cardiovascular risk reduction [7], this has not always been the case in practice, particularly for ezetimibe.

Ezetimibe reduces cholesterol absorption in the small intestine by targeting the Niemann-Pick C1 like 1 protein [8]. It is well-tolerated, and reduces LDL-C by about 20% as monotherapy, and by an additional 18–24% when used alongside statin therapy [9, 10]. Because of its LDL-C lowering potential, in 2002 the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and Health Canada, approved ezetimibe as a second-line medication for people with statin intolerance or in those unable to reach their lipid targets on statins alone. In 2003, ezetimibe entered the Canadian market, and in 2004, it was listed on Ontario’s drug benefits formulary.

Although ezetimibe lowers the reliable surrogate marker of LDL-C, its utility in preventing clinically important cardiovascular outcomes has remained controversial for more than a decade [11,12,13,14,15]. Evidence for a possible benefit of ezetimibe has been observed more recently in the Study of Heart and Renal Protection (SHARP) trial [16], and in the IMProved Reduction of Outcomes: Vytorin Efficacy International Trial (IMPROVE-IT) [10]. A recent pharmaco-economic modeling effort has also suggested that if statin monotherapy was insufficient to lower LDL-C, ezetimibe might be the next drug to add [17]. As ezetimibe is an inexpensive, easy to ingest, and well-tolerated medication, further evaluations of its effectiveness are necessary to guide prescribing [18].

Well-conducted, population-based drug studies can help to complement the findings of randomized controlled trials [19]. Although observational studies are considered lower on the pyramid of medical evidence, they can produce results that are more generalizable than clinical trials as they include a broader range of patients, many of whom would not meet the strict inclusion criteria of clinical trials. Observational drug studies can also help to ascertain how effective medications are in a “real-world” setting [19, 20].

Before executing such studies however, it is important to confirm study feasibility by quantifying patterns in drug prescriptions in routine care. In the current study, we aimed to examine how often ezetimibe has been prescribed to older adults following a hospitalization with an acute myocardial infarction (AMI) in Canada’s most populous province (Ontario). We also examined the predictors of new ezetimibe prescriptions.

Methods

Design and setting

We conducted a population-based retrospective cohort study to describe the frequency of new use of ezetimibe among older adults following a hospitalization for an AMI in Ontario, Canada. Ontario is Canada’s largest province with a population estimate of 13.9 million residents. In Ontario, people who are 65 years and older have universal healthcare including access to medications, hospital, diagnostic and physician services. Information on their use of these services is collected and maintained in the records of administrative databases held at the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES). Databases are linked using unique encoded identifiers.

Our study analysis was completed at ICES according to a pre-specified protocol (available from the authors upon request). We followed the guidelines for the reporting of studies using routinely collected healthcare data (RECORD) (Additional file 1) [21].

Sources of data

We ascertained baseline characteristics and outcomes using the records from several databases.

We used the Registered Persons Database of Ontario to collect vital statistics. This database contains demographic information on anyone who has ever received a healthcard in our province. We used the Canadian Institute for Health Information’s Discharge Abstract Database and the National Ambulatory Care Reporting System database to examine the medical comorbidities of patients. These databases contain patient diagnoses coded during inpatient and emergency room encounters, respectively. The diabetes and hypertension status of patients were collected from the Ontario Diabetes Database (ODD) and the Hypertension Database (HYPER). These databases were derived using validated coding algorithms (sensitivity of ODD 86% and specificity 97%; sensitivity of HYPER 73% and specificity 95%) [22, 23]. We used the Ontario Drug Benefit (ODB) database to capture prescription medications. This database contains records of all prescriptions dispensed to people age 65 and older with an error rate of less than 1% [24]. Limited use (LU) codes (codes required to prescribe drugs that are not listed under the general drug benefits formulary) [25], were ascertained from the ODB database. These codes were used to determine the reasons for new ezetimibe prescriptions (i.e. statin intolerance or contraindication to statin therapy [LU code 381], or failure to meet lipid targets on statin monotherapy [LU code 380]). We also used the drug identification number (DIN) database (IMS Brogan Inc., Mississauga, ON) to capture the dose of statin medications. Further, we examined the characteristics of physicians who prescribed ezetimibe through the ICES Physician Database (IPDB), and determined if patients were rostered to a family physician with the Client Agency Program Enrolment (CAPE) database. Physician visits, laboratory services, and additional medical comorbidities and procedures were obtained from the Ontario Health Insurance Plan (OHIP) database, which contains physician diagnostic and billing codes.

We used International Classification of Diseases 9th Revision (ICD-9, pre-2002), 10th Revision (ICD-10, 2002+), Canadian Classification of Diagnostic, Therapeutic, and Surgical Procedures (CCP, pre-2002), Canadian Classification of Health Interventions (CCI, 2002+), and OHIP billing and diagnostic codes to assess baseline comorbidities in the 5 years prior to their hospitalization for an AMI. Health services utilization was examined in the 1 year prior to their hospitalization (coding definitions provided in Additional file 2).

Patients

We included all patients with a valid healthcard number who had evidence of a hospitalization for an AMI (defined by ICD 10 code I21) between April 1, 2005 and March 31, 2014 in Ontario (the administrative [i.e. fiscal] years of 2005 to 2013). The following patients were then excluded: 1) those with a missing sex or age, and those < 66 years; 2) those who were not residents of Ontario at hospital admission; 3) those who died prior to their hospital discharge; and 4) those with evidence of a hospitalization for an AMI in the 5 years prior to cohort entry (to limit our cohort to patients who did not have an AMI in recent years). If patients had more than one hospitalization for an AMI over the study period, we examined their first hospitalization only. We also excluded patients with evidence of a prescription for ezetimibe in the 6 months prior to their hospitalization, to capture new ezetimibe prescriptions following their first myocardial infarction within the study period.

Outcomes

Our primary aim was to determine the percentage of patients with a new prescription for ezetimibe within 6 months of their hospital discharge. We chose 6 months of follow-up as we judged this to be a reasonable period of time in which high-risk patients would have lipid-lowering therapies initiated, titrated or changed to meet their LDL-C targets. In additional analyses, we detailed the characteristics of the new prescriptions (e.g. reason for ezetimibe prescription as determined by LU codes). We also ascertained the time between hospital discharge and a new prescription for ezetimibe, and we examined the duration of continuous use of ezetimibe, which was defined by the total number of days that the therapy was prescribed to patients allowing for a grace period between repeat prescriptions (1.5 times the days’ supply of the previous prescription). We further examined the predictors for a new ezetimibe prescription.

Statistical analysis

We used descriptive statistics to present the characteristics of patients newly prescribed and not prescribed ezetimibe within 6 months of their hospital discharge. Continuous variables are presented as means ± standard deviation (SD), and medians (interquartile range [IQR]). Binary variables are presented as proportions. We evaluated between-group differences using standardized differences, for which a value > 10% is considered to be meaningful [26].

We used both univariable and multivariable logistic regression (with backward selection, P value < 0.05) to identify the clinically relevant predictors for a new ezetimibe prescription following hospital discharge (Additional file 3). For our multivariable analyses, all predictor variables could be included in the final logistic regression model. Results are presented as odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI’s).

Results

Between April 1, 2005 and March 31, 2014, there were 167, 817 patients with a valid healthcard number hospitalized for an AMI in Ontario. A total of 71, 125 older adults were included in our study cohort (flow diagram in Additional file 4). Their mean age was 78 ± 8 years, and 45.8% were women.

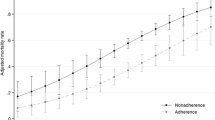

Only 1230 (1.7%) patients were newly prescribed ezetimibe within 6 months of their hospital discharge. This percentage increased after 2005 (7%), peaked in 2007 (16%), then appeared to decline to a rate of 2% in 2014 (Additional file 5).

When prescribed ezetimibe, the median number of days between hospital discharge and a new prescription was 63 (IQR 13–119 days). Patients were most often prescribed ezetimibe by their family physician (n = 509; 41.4%), followed by a cardiologist (n = 351; 28.5%). The majority were prescribed the therapy because they had not achieved their target LDL-C with statins (n = 888 [72.2%] were administered LU code 380). The remainder were prescribed ezetimibe in the setting of statin intolerance or a contraindication to the therapy (LU code 381). For those prescribed ezetimibe, the median duration of continuous use was 444 days (IQR 100–1266 days) or 1.2 years (IQR 0.3–3.5 years).

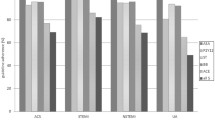

The characteristics of people newly prescribed and not prescribed ezetimibe within 6 months of their discharge are detailed in Table 1. Patients prescribed ezetimibe appeared younger, healthier, were less likely to have diabetes, hypertension or heart failure, and appeared more likely to be on high-intensity statins, fibrates or angiotensin receptor blockers.

In univariable analysis, significant positive predictors for a new ezetimibe prescription included: 1) being rostered to a family doctor; 2) use of high-intensity statin therapy; 3) having at least one lipid test post-discharge; 4) having a family physician visit within 30 days of discharge; and 5) having a specialist visit within 60 days of discharge. Patients less likely to receive a new prescription for ezetimibe were 1) older; 2) lived in long-term care; 3) had medical comorbidities including diabetes, chronic kidney disease, hypertension and congestive heart failure; and 4) had hospital admissions for AMIs in the latter years of study (Table 2).

In multivariable analysis, patients were more likely to receive ezetimibe if they: 1) lived in rural locations; 2) used high-intensity statin therapy; 3) had a pre-existing history of coronary artery disease; and 4) had a lipid test, or specialist visit after their discharge (Table 2). In contrast, 1) older patients; 2) long-term care residents; 3) men; 4) those with congestive heart failure; and 5) those with AMI hospitalizations in the latter years of our study were less likely to receive a new prescription for ezetimibe.

Discussion

Although some patients do not achieve guideline recommended LDL-C targets on statin monotherapy, and intolerance to statins has been described in 27% of statin treated patients and 36% of high-risk patients [27, 28], in our province, only a small proportion of high-risk older adults were newly prescribed ezetimibe after an AMI from 2005 to 2014.

The reasons for infrequent ezetimibe prescriptions in high-risk older adults could be manifold. For one, although older adults benefit from LDL-C lowering [29, 30], there remains controversy over the utility of therapy in people over the age of 80, and in those with medical comorbidities or functional impairment [31]. Ezetimibe may have also been infrequently prescribed as older patients can experience adverse side effects with combination therapies [32]. This may have dissuaded practitioners from prescribing ezetimibe as an add-on to statin therapy. Additionally, LU codes are required to prescribe ezetimibe to older adults in our province, and this additional administrative requirement may have deterred practitioners from writing prescriptions for the therapy.

Further, cholesterol management in general has been reported to be suboptimal in high-risk patients [33,34,35], especially in older adults [33]. In a previous study of 396, 077 older adults (median age 75) with cardiovascular disease or diabetes in Ontario, only a small proportion were prescribed statins (n = 75, 617 patients, 19.1%) [33]. In our study, there were some patients who did not have lipid profiles checked nor see a family doctor or a specialist in a timely fashion after their discharge. This gap in follow-up care might have contributed to infrequent prescriptions.

Ezetimibe prescriptions may have also been low as between 2007 and 2015 there was controversy about the utility of this therapy in preventing clinically important cardiovascular outcomes. In 2008, the ENHANCE trial compared the effectiveness of simvastatin alone vs. simvastatin plus ezetimibe on the progression of atherosclerosis in patients with familial hypercholesterolemia, as measured by carotid intima-media thickness [12]. Although ezetimibe lowered LDL-C, it did not slow the progression of atherosclerosis over 24 months. In subsequent similar trials of ezetimibe, there was also no observed cardiovascular benefit of the therapy based upon surrogate imaging and arterial markers [13,14,15].

Evidence for a possible benefit of ezetimibe in reducing cardiovascular outcomes was not observed until 2011 in patients with renal impairment who participated in the SHARP trial [16]. In those who took simvastatin plus ezetimibe vs. placebo alone, cardiovascular risk was reduced by 17%. In the absence of a monotherapy arm however, it was impossible to definitively ascribe incremental benefit to ezetimibe. The IMPROVE-IT trial published in June 2015 also reported a benefit of ezetimibe in preventing major cardiovascular outcomes. In this study, when ezetimibe was prescribed with moderate-intensity simvastatin to patients with a recent myocardial infarction, there was a lower risk of cardiovascular outcomes in the ezetimibe group (32.7% with an event in ezetimibe plus simvastatin group vs. 34.7% in the simvastatin monotherapy group, absolute risk reduction 2%, P < 0.001) [10]. With the small effect size observed, missingness in the data, and controversy about the choice of the control arm (moderate-intensity statin therapy, specifically simvastatin), the clinical relevance of these results still remain controversial. In fact, The Endocrinology and Metabolic Drug Advisory committee of the US FDA has since voted against expanding the indication of ezetimibe for cardiovascular protection [36]. In our study, we did find that prescriptions for ezetimibe increased following its release on the provincial formulary in 2004, but appeared to decline after the publication of the ENHANCE trial. Ezetimibe prescriptions were also less common in the latter years of our study. A decline in the use of ezetimibe following ENHANCE has also been described in younger individuals with private drug coverage [37].

Interestingly, we also found that older men appeared less likely (23% decrease in odds) to be prescribed ezetimibe. Although there has been controversy about the impact of cholesterol on cardiovascular outcomes amongst the sexes [31], guidelines including the Second Adult Treatment Panel of the National Cholesterol Education Program and the Canadian Lipid Guidelines (both in force during our study’s time period) recommended similar cholesterol management in elderly women and men [27, 38, 39]. This difference was not apparent in the univariable analysis, but was significant in the multivariable analysis, implying a difference in the risk profiles between men and women.

Whatever the reasons for its infrequent use in high-risk patients in our region, our findings do suggest that efforts to examine the effectiveness of ezetimibe in preventing clinically important cardiovascular outcomes in Ontario would face a number of methodological challenges. With the limited number of prescriptions, proposed studies would likely suffer from low sample size and statistical power [40]. Further in routine care, patients did not stay on ezetimibe for very long (median 1.2 years, IQR 0.3 to 3.5 years), whereas in clinical trials, some took the therapy for up to 6 years. This would impact the attribution of ezetimibe to any observed outcomes. The choice of an appropriate control group would also be challenging due to potential confounding by indication (currently ezetimibe can only be prescribed with an appropriate LU code). Furthermore, changes in statin co-prescriptions and the initiation of other cardioprotective therapies during the follow-up period, would need to be considered and managed carefully in statistical analyses.

Comparison with previous literature

To our best knowledge, the real-world use of ezetimibe in high-risk older adults with publically funded drug benefits has not been examined. In a younger group of Danish people with private drug benefits (2011–2012), those with a prior AMI, women, and those on higher-potency statins were more likely to be treated with ezetimibe [41]. Unlike in our study, patients with higher incomes were also more likely to be treated. This may be because in our country, lipid therapies are covered for older adults by our publically funded healthcare system.

Strengths and weaknesses

Our study has several strengths. We examined patterns of ezetimibe use in a large group of representative, high-risk older adults in routine-care (n = 71, 125). We ascertained the demographics, medical comorbidities, medications and healthcare utilization of people who were prescribed the therapy, and detailed the predictors of a new prescription. We also noted some characteristics of new ezetimibe prescriptions.

There are some weaknesses to our study. Our results are not fully generalizable to younger populations with private drug benefits, nor to individuals who live outside of Ontario. The availability of data at the time of our study did not allow us to examine the impact of IMPROVE-IT on ezetimibe prescribing patterns. PCSK9 (proprotein convertase subtilisin-kexin type 9) inhibitors are also now available in our region, and can only be prescribed to people who have sub-target lipid control while taking both statins and ezetimibe. Since these medications did not enter the market until 2015, we could not evaluate their impact on ezetimibe prescribing. Further the data that we used were collected for administrative purposes, and were not specifically designed for this research study.

Conclusions

Over the last decade in Ontario, only a small proportion of high-risk older adults received a prescription for ezetimibe within 6 months of an AMI. In this setting, a real-world drug effectiveness study would face a number of methodological challenges. Our work highlights the importance of examining drug prescription patterns prior to conducting drug effectiveness or safety studies in routine care.

Abbreviations

- AMI:

-

Acute myocardial infarction

- CAPE:

-

Client agency program enrolment database

- CCI:

-

Canadian classification of health interventions

- CCP:

-

Canadian classification of diagnostic, therapeutic and surgical procedures

- DIN:

-

Drug information number

- FDA:

-

Food and drug administration

- HYPER:

-

Hypertension database

- ICD:

-

International classification of diseases

- ICES:

-

Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences

- IPDB:

-

ICES physician database

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- LDL-C:

-

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- LU:

-

Limited use

- ODB:

-

Ontario drug benefits

- ODD:

-

Ontario diabetes database

- OHIP:

-

Ontario Health Insurance Program

- PCSK9:

-

Proprotein convertase subtilisin-kexin type 9

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

References

Baigent C, Keech A, Kearney PM, Blackwell L, Buck G, Pollicino C, et al. Efficacy and safety of cholesterol-lowering treatment: prospective meta-analysis of data from 90,056 participants in 14 randomised trials of statins.[see comment][erratum appears in lancet. 2005 Oct 15-21;366(9494):1358]. Lancet. 2005;366:1267–78.

Mancini GBJ, Baker S, Bergeron J, Fitchett D, Frohlich J, Genest J, et al. Diagnosis, prevention, and Management of Statin Adverse Effects and Intolerance: Canadian consensus working group update (2016). Can J Cardiol. 2016;32(7 Suppl):S35–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2016.01.003.

Kashani A, Phillips CO, Foody JM, Wang Y, Mangalmurti S, Ko DT, et al. Risks associated with statin therapy: a systematic overview of randomized clinical trials. Circulation. 2006;114:2788–97.

Robinson JG, Davidson MH. Combination therapy with ezetimibe and simvastatin to achieve aggressive LDL reduction. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2006;4:461–76.

Wei MY, Ito MK, Cohen JD, Brinton EA, Jacobson TA. Predictors of statin adherence, switching, and discontinuation in the USAGE survey: understanding the use of statins in America and gaps in patient education. Journal of Clinical Lipidology. 2013;7:472–83.

Committee W, Lloyd-Jones DM, Morris PB, Ballantyne CM, Birtcher KK. Daly DD Jr, DePalma SM, Minissian MB, Orringer CE SSJ. 2016 ACC expert consensus decision pathway on the role of non-Statin therapies for LDL-cholesterol lowering in the Management of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease Risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology Task Force on clinical expert cons. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:92–125.

Hegele RA, Gidding SS, Ginsberg HN, McPherson R, Raal FJ, Rader DJ, et al. Nonstatin low-density lipoprotein-lowering therapy and cardiovascular risk reduction-statement from ATVB council. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35:2269–80. https://doi.org/10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.306442.

Davidson MH. Newer pharmaceutical agents to treat lipid disorders. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2003;5:463–9.

Bruckert E, Giral P, Tellier P. Perspectives in cholesterol-lowering therapy: the role of ezetimibe, a new selective inhibitor of intestinal cholesterol absorption. Circulation. 2003;107:3124–8.

Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, McCagg A, White JA, Theroux P, et al. Ezetimibe added to Statin therapy after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2387–97. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1410489.

McPherson R, Hegele RA. Ezetimibe: rescued by randomization (clinical and mendelian). Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35:e13–5. https://doi.org/10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.305012.

Kastelein JJP, Akdim F, Stroes ESG, Zwinderman AH, Bots ML, Stalenhoef AFH, et al. Simvastatin with or without ezetimibe in familial hypercholesterolemia. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1431–43. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0800742.

Taylor AJ, Villines TC, Stanek EJ, Devine PJ, Griffen L, Miller M, et al. Extended-release niacin or ezetimibe and carotid intima-media thickness. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(22):2113. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0907569.

Villines TC, Stanek EJ, Harm PD, Devine PJ, Turco M, Miller M, et al. The ARBITER 6-HALTS trial ( arterial biology for the investigation of the treatment effects of reducing cholesterol 6 – HDL and LDL treatment strategies in atherosclerosis ). Jac. 2010;55:2721–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2010.03.017.

West AM, Anderson JD, Meyer CH, Epstein FH, Wang H, Hagspiel KD, et al. The effect of ezetimibe on peripheral arterial atherosclerosis depends upon statin use at baseline. Atherosclerosis. 2011;218:156–62.

Baigent C, Landray MJ, Reith C, Emberson J, Wheeler DC, Tomson C, et al. The effects of lowering LDL cholesterol with simvastatin plus ezetimibe in patients with chronic kidney disease (study of heart and renal protection): a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet (London, England). 2011;377:2181–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60739-3.

Robinson JG, Huijgen R, Ray K, Persons J, Kastelein JJP, Pencina MJ. Determining when to add Nonstatin therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:2412–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2016.09.928.

Burke AC, Dron JS, Hegele RA, Huff MW. PCSK9: regulation and target for drug development for Dyslipidemia. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2017;57:223–44. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010716-104944.

Möller H-J. Effectiveness studies: advantages and disadvantages. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2011;13:199–207. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21842617. Accessed 19 Sep 2017

Glasser SP, Salas M, Delzell E. Importance and challenges of studying marketed drugs: what is a phase IV study? Common clinical research designs, registries, and self-reporting systems. J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;47:1074–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091270007304776.

Benchimol EI, Smeeth L, Guttmann A, Harron K, Moher D, Petersen I, et al. The REporting of studies conducted using observational routinely-collected health data (RECORD) statement. PLoS Med. 2015;12:e1001885. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001885.

Hux JE, Ivis F, Flintoft V, Bica A. Diabetes in Ontario: determination of prevalence and incidence using a validated administrative data algorithm. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:512–6.

Tu K, Campbell NR, Chen Z-L, Cauch-Dudek KJ, McAlister FA. Accuracy of administrative databases in identifying patients with hypertension. Open Med. 2007;1:e18–26. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2801913&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. Accessed 4 Jan 2017

Levy AR, O’Brien BJ, Sellors C, Grootendorst P, Willison D. Coding accuracy of administrative drug claims in the Ontario drug benefit database. Can J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;10:67–71.

Care M of H and LT. Ontario Public Drug Programs. 2016. http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/drugs/limited_use_mn.aspx. Accessed 4 Jan 2016.

Austin PC. Using the standardized difference to compare the prevalance of a binary variable between two groups in observational studies. Commun Stat Simulat. 2009;38:1228.

Anderson TJ, Grégoire J, Hegele RA, Couture P, Mancini GBJ, McPherson R, et al. 2012 update of the Canadian cardiovascular society guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of dyslipidemia for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in the adult. Can J Cardiol. 2013;29:151–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2012.11.032.

Bourgault C, Davignon J, Fodor G, Gagné C, Gaudet D, Genest J, et al. Statin therapy in Canadian patients with hypercholesterolemia: the Canadian lipid study -- observational (CALIPSO). Can J Cardiol. 2005;21:1187–93. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16308595. Accessed 5 Jan 2017

Neil HAW, DeMicco DA, Luo D, Betteridge DJ, Colhoun HM, Durrington PN, et al. Analysis of efficacy and safety in patients aged 65-75 years at randomization: collaborative Atorvastatin diabetes study (CARDS). Diabetes Care. 2006;29:2378–84. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc06-0872.

Wenger NK, Lewis SJ, Herrington DM, Bittner V, Welty FK. Outcomes of using high- or low-dose atorvastatin in patients 65 years of age or older with stable coronary heart disease. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:1–9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17606955. Accessed 5 Jan 2017

Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Rifkind BM, Kuller LH. Cholesterol lowering in the elderly population. Coordinating Committee of the National Cholesterol Education Program. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:1670–8.

LaRosa JC. Treatment of cholesterol in the elderly: statins and beyond. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2014;16:385.

Ko DT, Mamdani M, Alter DA. Lipid-lowering therapy with statins in high-risk elderly patients: the treatment-risk paradox. JAMA. 2004;291:1864–70. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.291.15.1864.

Austin PC, Mamdani MM, Juurlink DN, Alter DA, Tu JV. Missed opportunities in the secondary prevention of myocardial infarction: an assessment of the effects of statin underprescribing on mortality. Am Heart J. 2006;151:969–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2005.06.034.

Xanthopoulou I, Davlouros P, Siahos S, Perperis A, Evangelia Z, Alexopoulos D. First-line treatment patterns and lipid target levels attainment in very high cardiovascular risk outpatients. Lipids Heal Dis. 2013;12:170. https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-511X-12-170.

Wood S. FDA: No cardiovascular event reduction claim for ezetimibe. TCTMD/The Heart beat. 2016. https://www.tctmd.com/news/fda-no-cardiovascular-event-reduction-claim-ezetimibe. Accessed 4 Jan 2017.

Ross JS, Frazee SG, Garavaglia SB, Levin R, Novshadian H, C a J, et al. Trends in use of Ezetimibe after the ENHANCE trial, 2007 through 2010. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;6520:1486–93. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.3404.

Genest J, McPherson R, Frohlich J, Anderson T, Campbell N, Carpentier A, et al. 2009 Canadian cardiovascular society/Canadian guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of dyslipidemia and prevention of cardiovascular disease in the adult - 2009 recommendations. Can J Cardiol. 2009;25:567–79. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2782500&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. Accessed 5 Jan 2017

Grundy SM. Approach to lipoprotein management in 2001 National Cholesterol Guidelines. Am J Cardiol. 2002;90:11i–21i. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12419477. Accessed 5 Jan 2017

Gordis L. Epidemiology. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2009.

Wallach-Kildemoes H, Hansen EH. Sociodemographic and diagnostic characteristics of prescribing a second-line lipid-lowering medication: Ezetimibe used as initial medication, switch from statins, or add-on medication. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;71:1245–54.

Acknowledgements

We thank IMS Brogan Inc. for use of their Drug Information Database. Parts of this material are based upon data and information compiled and provided by the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI). However, the analyses, conclusions, opinions and statements expressed herein are those of the authors, and not necessarily those of CIHI.

Funding

This study was supported by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES) Western site. ICES is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC). Core funding for ICES Western is provided by the Academic Medical Organization of Southwestern Ontario (AMOSO), the Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry (SSMD), Western University, and the Lawson Health Research Institute (LHRI). RAH has received operating grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Foundation Grant), the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario (T-000353), and Genome Canada through Genome Quebec (award 4530). The research was conducted by members of the ICES Kidney, Dialysis and Transplantation team who are supported by a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR).

The opinions, results and conclusions are those of the authors and are independent from the funding sources. No endorsement by ICES, AMOSO, SSMD, LHRI, CIHR, the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario, Genome Canada or the MOHLTC is intended or should be inferred.

Availability of data and materials

The data set from this study is held securely in coded form at ICES. While data sharing agreements prohibit ICES from making the data set publicly available, access may be granted to those who meet pre-specified criteria for confidential access. More information is available at www.ices.on.ca/DAS.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KKC contributed to the design of the study, the interpretation of the results, and the drafting of the manuscript. SZS contributed to the design of the study, the acquisition and analysis of data, the interpretation of the results, and she revised the manuscript critically for its content. EM contributed to the acquisition of data and its analysis, and he revised the manuscript critically for its content. RAH contributed to the conception and design of the study, the interpretation of results, and the drafting and revising of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Our study was approved by the research ethics board at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre (Toronto, Canada). Informed consent was not required from patients, as ICES is a named entity under Ontario’s Personal Health Information Protection Act and is able to receive and use health information to examine the province’s healthcare system.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

RAH has received honoraria for membership on advisory boards and speakers’ bureaus for Aegerion, Amgen, Gemphire, Lilly, Merck, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sanofi and Valeant. There are no other conflicts of interest to disclose.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

RECORD checklist of recommendations for the reporting of studies conducted using routinely collected health data. (DOCX 17 kb)

Additional file 2:

Coding definitions for demographic characteristics and comorbidities. (DOCX 17 kb)

Additional file 3:

Predictor variables for a new ezetimibe prescription. (DOCX 13 kb)

Additional file 4:

Flow diagram of patient inclusion and exclusion into study cohort. (DOCX 25 kb)

Additional file 5:

Percentage of older adults with a new ezetimibe prescription following a hospital encounter for an acute myocardial infarction. (DOCX 50 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Clemens, K.K., Shariff, S.Z., McArthur, E. et al. Ezetimibe prescriptions in older Canadian adults after an acute myocardial infarction: a population-based cohort study. Lipids Health Dis 17, 8 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-017-0649-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-017-0649-5