Abstract

Background

Raoultella planticola, a Gram-negative, aerobic bacillus commonly isolated from soil and water, rarely causes invasive infections in humans. Septic shock from R. planticola after burn injury has not been previously reported.

Case presentation

A 79-year-old male was admitted to the emergency intensive care unit after extensive flame burn injury. He accidently caught fire while burning trash and plunged into a nearby tank filled with contaminated rainwater to extinguish the fire. The patient developed septic shock on day 10. The blood culture detected R. planticola, which was identified using the VITEK-2 biochemical identification system. Although appropriate antibiotic treatment was continued, the patient died on day 12.

Conclusions

Clinicians should be aware of fatal infections in patients with burn injury complicated by exposure to contaminated water.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Raoultella planticola is a Gram-negative, aerobic bacillus commonly found in soil and aquatic environments [1]. R. planticola infection is a relatively uncommon clinical entity, but sometimes causes fatal infection in immunocompromised patients [2]. Contaminated water used to extinguish a fire can lead to severe wound infections caused by waterborne microorganisms [3]. To our knowledge, R. planticola bacteremia has not been previously described in a burn patient. Herein, we report a case of fatal septic shock due to R. planticola bacteremia following flame burn injury complicated by exposure to contaminated water to extinguish the fire.

Case presentation

A 79-year-old male was referred to our tertiary hospital after extensive flame burn injury. He accidently caught fire while burning trash in a steel drum. The fire was extinguished when he plunged into a nearby water storage tank filled with dirty rainwater. His medical history was unremarkable except for hemiparesis of the right side as sequelae of ischemic stroke.

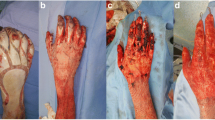

Upon arrival in the emergency department, he was alert and oriented, but he appeared distressed, complaining of dyspnea. His vital signs were as follows: Glasgow Coma Scale score: 15 (E4V5M6); respiratory rate: 20 breaths/min; pulse rate: 86 beats/min, blood pressure: 194/64 mmHg; and oxygen saturation: 99% via 10 L/min through a reservoir mask. Burn wounds were distributed on his face, neck, anterior trunk, and both upper extremities. Total body surface area (TBSA) affected was 35, 30% with third-degree burns and 5% with deep dermal burns (Fig. 1). As the patient had extensive burns, including on his face and neck, he was immediately intubated and fluid resuscitation was initiated. The burned areas were gently scrubbed with soapy water and covered with non-adherent dressing. The patient was admitted to the emergency intensive care unit.

Silver-coated dressings were applied 2 days after the injury to prevent wound infection. As Aeromonas hydrophila was isolated in the wound culture on day 5, 4.5 g doses of piperacillin/tazobactam three times daily were initiated. The medications were continued to treat Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which was isolated in the wound on day 7. Tangential debridement and skin grafting were performed for 30% of his TBSA on day 7. The procedure was successfully completed in 3 h.

Two days after surgery, the patient developed septic shock. White blood cell counts showed 33,470/μL with 97.7% neutrophils. His lactate and procalcitonin levels were found to be increased (Fig. 2). Noradrenaline infusion was initiated to support blood pressure following adequate fluid resuscitation. Empirical antibiotic therapy with daptomycin was administered and two sets of blood cultures were obtained. His abdomen was soft and not distended, without any evidence of intra-abdominal infections including cholecystitis or bowel necrosis based on laboratory data and radiological findings. The patient developed refractory septic shock despite the addition of vasopressin. Piperacillin/tazobactam was replaced by 1 g doses of meropenem three times daily for concerning antibiotic resistance on day 10; however, the patient’s condition continued to deteriorate. His blood culture was positive for R. planticola, which was identified using the VITEK-2 biochemical identification system. The strain was susceptible to both piperacillin/tazobactam and meropenem. The results of antimicrobial susceptibility testing are summarized in Table 1. Cultures of the patient’s urine and sputum at the onset of septic shock were revealed to be negative. Repetitive burn wound cultures yielded P. aeruginosa, which was sensitive to both piperacillin/tazobactam and meropenem with minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of ≦ 2 μg/mL and MIC ≦ 0.5 μg/mL, respectively, and methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA). The patient ultimately expired due to refractory septic shock and subsequent multiple organ failure on day 12. Figure 2 shows the patient’s clinical course over the 12 days after admission.

Discussion

This is the first report of fatal septic shock due to R. planticola bacteremia after flame burn injury. Extinguishing a fire with contaminated water can cause infection, and an impaired immune response after extensive burn injury may be responsible for the development of fatal septic shock.

Raoultella planticola is a Gram-negative, non-motile, encapsulated bacillus previously classified in the genus Klebsiella, including the species K. planticola and K. trevisanii [4]. In 1986, both microorganisms were combined as K. planticola because of deoxyribonucleic acid similarities [5]. The new genus Raoultella was established in 2001 on the basis of 16S rRNA and rpoB sequences [4]. R. planticola is considered an environmental organism commonly isolated from water and soil and does not typically cause human infections [6]. In recent years, infections due to R. planticola have been reported, including necrotizing fasciitis, bacteremia, severe pancreatitis, cholecystitis, cholangitis, urinary tract infection, and pneumonia [1, 6,7,8,9,10,11]. These infections mainly occur in immunocompromised patients with conditions such as cancer and hematological malignancies, and those post-transplant and/or with comorbidities including diabetes and alcoholic cirrhosis [1, 2, 8].

Several infection routes are possible in our case. Although the burn wound culture had been negative for R. planticola, the burn wound may have been a possible infection route, considering that A. hydrophila, the most common cause of wound infection related to a history of body immersion in untreated water [3], had been identified initially. In addition, both R. planticola and A. hydrophila are deemed uncommon organisms isolated from outbreaks in burn patients [12]. O’Connell et al. [13] described a case of soft tissue infection caused by R. planticola in a healthy individual 1 week after injury to the thumb in a soiled environment. Otherwise, since the patient had plunged into a tank of contaminated water to extinguish the fire on his body, including his face, it was speculated that the oral or gastrointestinal routes might also have contributed to the infection. Lam et al. [6] reported a case of R. planticola infection 4 days after a patient with metastatic cancer consumed seafood. Furthermore, extensive burn injury is well-known to lead to host immune system impairment, rendering the patient susceptible to opportunistic infections [14]. Also, escharotomy and skin grafting may be predisposed to bacteremia, as previous reports have suggested the potential risk factors of R. planticola bacteremia in invasive medical procedures [9].

Clinical outcomes of R. planticola infections have been fair unless polymicrobial bacteremia was present [2, 15]. Chun et al. summarized 20 cases of R. planticola bacteremia, six of which were polymicrobial infections; half of those failed to recover [2]. Even though R. planticola as a sole pathogen had been isolated from blood cultures in the present case, P. aeruginosa and MSSA burn wound infections may accelerate the patient’s development of refractory septic shock. In the past few years, carbapenem-resistant R. planticola cases have been reported sporadically, resulting in unfavorable outcomes [15, 16]. In the present case, empiric administration of piperacillin/tazobactam had been initiated prior to the development of septic shock and isolated organisms were susceptible to piperacillin/tazobactam and meropenem. As limited data is available regarding this pathogen and its virulence, the mechanisms of its pathogenesis in the present case with poor outcomes remained unclear. We cannot assert whether the clinical course was associated with R. planticola bacteremia; however, it may have played a critical role in the development of fatal septic shock. Further research regarding its virulence is necessary.

The effects of prophylactic antibiotics use for patients with severe burns remains controversial, as a small volume and low-quality data is available [17]. However, a recent systematic review suggests that prophylactic antibiotics may be beneficial for patients requiring mechanical ventilation [18]. Although a history of exposure to soil or water is not always essential for Aeromonas spp. infection in burn patients [19], a history of extinguishing the fire with dirty water should alert the physician to consider the possibility of infection from A. hydrophila and other microorganisms, including P. aeruginosa and Bacillus cereus [3]. Hence, initial therapeutic antibiotics may contribute to favorable outcomes in such a specific situation.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of fatal septic shock due to R. planticola bacteremia, which was an extremely unusual pathogen in a burn patient. Exposure to contaminated water to extinguish a fire may contribute to R. planticola infection. In addition, an impaired immune system due to an extensive third degree burn may further progress to refractory septic shock. Initial empirical antibiotics may be beneficial for burn patients with aquatic exposure.

Conclusions

We reported a rare case of fatal septic shock due to R. planticola bacteremia following flame burn injury. Clinicians should be aware of such fatal infections when a patient is exposed to contaminated water.

Abbreviations

- TBSA:

-

total body surface area

- MIC:

-

minimum inhibitory concentration

- MSSA:

-

methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus

References

Kim SH, Roh KH, Yoon YK, Kang DO, Lee DW, Kim MJ, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis involving the chest and abdominal wall caused by Raoultella planticola. BMC Infect Dis. 2012;12:59.

Chun S, Yun JW, Huh HJ, Lee NY. Low virulence? Clinical characteristics of Raoultella planticola bacteremia. Infection. 2014;42:899–904.

Ribeiro NF, Heath CH, Kierath J, Rea S, Duncan-Smith M, Wood FM. Burn wounds infected by contaminated water: case reports, review of the literature and recommendations for treatment. Burns. 2010;36:9–22.

Drancourt M, Bollet C, Carta A, Rousselier P. Phylogenetic analyses of Klebsiella species delineate Klebsiella and Raoultella gen. nov., with description of Raoultella ornithinolytica comb. nov., Raoultella terrigena comb. nov. and Raoultella planticola comb. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2001;51:925–32.

Gavini F, Izard D, Grimont PAD, Beji A, Ageron E, Leclerc H. Priority of Klebsiella planticol Bagley, Seidler, and Brenner 1982 over Klebsiella trevisani Ferragut, Izard, Gavini, Kersters, DeLey, and Leclerc 1983. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1986;36:486.

Lam PW, Salit IE. Raoultella planticola bacteremia following consumption of seafood. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2014;25:e83–4.

Alves MS, Riley LW, Moreira BM. A case of severe pancreatitis complicated by Raoultella planticola infection. J Med Microbiol. 2007;56:696–8.

Ershadi A, Weiss E, Verduzco E, Chia D, Sadigh M. Emerging pathogen: a case and review of Raoultella planticola. Infection. 2014;42:1043–6.

Yokota K, Gomi H, Miura Y, Sugano K, Morisawa Y. Cholangitis with septic shock caused by Raoultella planticola. J Med Microbiol. 2012;61:446–9.

Skelton WP 4th, Taylor Z, Hsu J. A rare case of Raoultella planticola urinary tract infection in an immunocompromised patient with multiple myeloma. IDCases. 2017;8:9–11.

Westerveld D, Hussain J, Aljaafareh A, Ataya A. A rare case of Raoultella planticola pneumonia: an emerging pathogen. Respir Med Case Rep. 2017;21:69–70.

Yun HC, Tully CC, Mende K, Castillo M, Murray CK. A single-center, six-year evaluation of the role of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis in suspected burn center outbreaks. Burns. 2016;42:1323–30.

O’Connell K, Kelly J, Niriain U. A rare case of soft-tissue infection caused by Raoultella planticola. Case Rep Med. 2010;2010:134086.

Bohr S, Patel SJ, Vasko R, Shen K, Golberg A, Berthiaume F, et al. The role of CHI3L1 (Chitinase-3-Like-1) in the pathogenesis of infections in burns in a mouse model. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0140440.

Demiray T, Koroglu M, Ozbek A, Altindis M. A rare cause of infection, Raoultella planticola: emerging threat and new reservoir for carbapenem resistance. Infection. 2016;44:713–7.

Castanheira M, Deshpande LM, DiPersio JR, Kang J, Weinstein MP, Jones RN. First descriptions of blaKPC in Raoultella spp. (R. planticola and R. ornithinolytica): report from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:4129–30.

Avni T, Levcovich A, Ad-El DD, Leibovici L, Paul M. Prophylactic antibiotics for burns patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010;340:c241.

Ramos G, Cornistein W, Cerino GT, Nacif G. Systemic antimicrobial prophylaxis in burn patients: systematic review. J Hosp Infect. 2017;97:105–14.

Chim H, Song C. Aeromonas infection in critically ill burn patients. Burns. 2007;33:756–9.

Authors’ contributions

TY, HN, HI, TO and TW cared for the patient. TY and HI drafted the manuscript. TY, TO, and TW collected and analyzed the data. HN, KT, and AN evaluated the draft and suggested revisions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s daughter for publication of this case report and accompanying photograph.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was obtained for this report.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Yumoto, T., Naito, H., Ihoriya, H. et al. Raoultella planticola bacteremia-induced fatal septic shock following burn injury. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob 17, 19 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12941-018-0270-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12941-018-0270-0