Abstract

Background

Nitrogen dioxide (NO2) is a pervasive urban pollutant originating primarily from vehicle emissions. Ischemic heart disease (IHD) is associated with a considerable public health burden worldwide, but whether NO2 exposure is causally related to IHD morbidity remains in question. Our objective was to determine whether short term exposure to outdoor NO2 is causally associated with IHD-related morbidity based on a synthesis of findings from case-crossover and time-series studies.

Methods

MEDLINE, Embase, CENTRAL, Global Health and Toxline databases were searched using terms developed by a librarian. Screening, data extraction and risk of bias assessment were completed independently by two reviewers. Conflicts between reviewers were resolved through consensus and/or involvement of a third reviewer. Pooling of results across studies was conducted using random effects models, heterogeneity among included studies was assessed using Cochran’s Q and I2 measures, and sources of heterogeneity were evaluated using meta-regression. Sensitivity of pooled estimates to individual studies was examined using Leave One Out analysis and publication bias was evaluated using Funnel plots, Begg’s and Egger’s tests, and trim and fill.

Results

Thirty-eight case-crossover studies and 48 time-series studies were included in our analysis. NO2 was significantly associated with IHD morbidity (pooled odds ratio from case-crossover studies: 1.074 95% CI 1.052–1.097; pooled relative risk from time-series studies: 1.022 95% CI 1.016–1.029 per 10 ppb). Pooled estimates for case-crossover studies from Europe and North America were significantly lower than for studies conducted elsewhere. The high degree of heterogeneity among studies was only partially accounted for in meta-regression. There was evidence of publication bias, particularly for case-crossover studies. For both case-crossover and time-series studies, pooled estimates based on multi-pollutant models were smaller than those from single pollutant models, and those based on older populations were larger than those based on younger populations, but these differences were not statistically significant.

Conclusions

We concluded that there is a likely causal relationship between short term NO2 exposure and IHD-related morbidity, but important uncertainties remain, particularly related to the contribution of co-pollutants or other concomitant exposures, and the lack of supporting evidence from toxicological and controlled human studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Nitrogen dioxide (NO2) is a pervasive urban pollutant originating primarily from vehicle emissions, but also more broadly from any combustion in air [1, 2]. Other important contributors in areas with specific point sources include industrial sources and fossil fuel powered electric power generating stations [1, 2]. While ambient concentrations of NO2 have declined considerably in North America, Europe, Japan and South Korea, concentrations are increasing in other areas (e.g. China, North Korea and Taiwan) [3]. Numerous studies have evaluated health effects of nitrogen dioxide on diverse body systems. In particular, respiratory adverse effects have exhibited a relatively consistent association with NO2 in epidemiological studies, and these associations are supported by consistent toxicological and human clinical evidence of effects on the respiratory system [1, 2].

As a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, ischemic heart disease (IHD), including myocardial infarction and angina pectoris, is associated with a considerable public health burden [4]. Given its high prevalence, even relatively small incremental risks associated with air pollution exposure represent a substantial preventable burden on health. Nawrot et al. estimated that traffic exposure was associated with the largest population attributable fraction (PAF-7.4%) of all (including behavioural) triggers of myocardial infarction, while particulate matter was also associated with a substantial PAF (4.8%) [5]. However, whether NO2 exposure is causally related to IHD morbidity remains an unresolved question. A particular complicating factor is whether NO2 itself is to blame, or whether it is simply acting as a marker for specific air pollution sources i.e. emissions from vehicles [6, 7]. Carbon monoxide and certain chemical components of fine particulate matter, also primarily originating from vehicle emissions, are key potential confounders, given their well-established pathophysiological mechanisms of action on cardiac ischemia [8]. Effects of NO2 could also be confounded by other concomitant traffic-related exposures such as noise or stress [5]. We are aware of two previous systematic reviews/ meta-analyses which have evaluated the short term association of NO2 and IHD morbidity [9, 10]. These included primary studies published up to 2011 only, provided only limited evaluation of sources of heterogeneity, and did not examine whether the magnitude of effect differed between single and multi-pollutant models. In Mills et al.’s systematic review [10], study quality/risk of bias was not assessed. Only Mustafic et al. [9] and two other systematic reviews and meta-analyses have examined particulate matter and IHD morbidity [11, 12]. Our objective is therefore to determine whether short term exposure to outdoor NO2 is causally associated with morbidity from IHD based on an up to date synthesis of the available evidence.

Methods

Literature searches

MEDLINE, Embase, CENTRAL, Global Health and Toxline databases were searched using terms developed by a librarian (see Additional File 1). The search strategy underwent Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS) [13]. Searches were last updated August 27, 2019. Inclusion criteria were as follows: Participants/population: Humans; Intervention(s), exposure(s): Exposure to outdoor NO2 (and other oxides of nitrogen); Comparator(s)/control: Lower levels of exposure; Main outcomes: Counts of hospital admissions, emergency visits, physician office visits for IHD (including myocardial infarction (MI) and angina pectoris (AP)). Publications in abstract form only were excluded. Publications in English or French were included and there were no restrictions on publication date. Effect measures considered were: morbidity effects reported as regression coefficients, odds ratios or relative risks associated with exposures over days to weeks, expressed per specified increment in exposure. The present review is one part of a series of reviews of effects of NO2, all of which were included in the original search. Other reviews pertain to non-asthma respiratory morbidity related to short term exposure, and mortality related to long term exposure [14]. Studies were selected for the present review if reported outcomes matched the inclusion criteria specified above.

Screening, data extraction and risk of bias assessment

Screening, data extraction and risk of bias assessment were completed independently by two reviewers in DistillerSR. Conflicts between reviewers were resolved through consensus and/or involvement of a third reviewer. All studies retrieved from literature searches were screened for relevance based on title and abstract according to the above inclusion criteria. Where relevance could not be determined based on abstract and title, the full text was reviewed. Manual searches were also completed of reference lists of all relevant studies. Bibliographic data, study location and timing, design, population age group(s), sample size, outcome (hospital admission, emergency visit, physician visit), diagnosis (including ICD code(s) if available), method of exposure assessment, pollutant (including name, averaging time, units, lag, descriptive statistics), type of regression model, effect measure and standard error or confidence interval, model covariates (potential confounders) and their specification were extracted from all studies meeting inclusion criteria. When single pollutant results were presented for multiple lag times, we extracted the most highly statistically significant result (regardless of the direction of the association), or that reported by the authors as their primary finding. Results from multi-pollutant models that resulted in the greatest reduction in magnitude of effect compared to single pollutant results were selected in order to bracket the magnitude of effect from each study. Results expressed per pollutant increment expressed in μg/m3 were converted to parts per billion [15], and those based on 1 h maximum exposures were multiplied by 1.9 (the average ratio of 1 h maximum to 24 h average NO2 in Canadian cities). Where required data were not provided, authors were contacted by e-mail. In some instances Engauge Digitizer [16] was employed to extract numeric results presented only in graph form. Modifications of the Navigation Guide systematic review methodology [17] based on earlier systematic reviews of time-series and case-crossover studies [9, 18,19,20] as well as methodological reviews [21, 22], were employed to evaluate risk of bias according to the following domains: exposure assessment, confounding, outcome assessment, completeness of outcome data, selective outcome reporting, conflict of interest and other sources of bias.

Data analysis

The case-crossover approach can be regarded as an application of log-linear time series analysis if the time window of the case-crossover is comparable to the smoothing function on time in the time series [23]. However, since this condition may not be uniformly satisfied across all reviewed studies, and because case-crossover and time-series studies express effects using different measures of association (odds ratios and relative risks respectively), we analyzed them separately. Pooling of results across studies was conducted using random effects models computed using Restricted Maximum Likelihood (REML) estimation, with sensitivity analyses employing Dersimonian and Laird and Empirical Bayes estimators [24]. Heterogeneity among included studies was assessed using Cochran’s Q and I2 measures, and sources of heterogeneity were evaluated using meta-regression [24]. Sensitivity of pooled estimates to individual studies was examined using Leave One Out analysis and publication bias was evaluated using Funnel plots, Begg’s and Egger’s tests, and trim and fill [24]. Subgroup analyses were conducted by region, age group, sex, and single vs. multi-pollutant models. Analysis was conducted in R version 3.6.0 [25] using the metafor package [24]. The systematic review protocol is registered with PROSPERO (CRD42018084497) [14].

Results

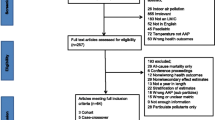

A Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) diagram summarizing disposition of studies identified in literature searches is shown in Fig. 1. As indicated earlier, the present review is one part of a series of reviews of effects of NO2 on multiple outcomes, all of which were included in the original search, which is reflected in numeric results reported in Fig. 1. Thirty-eight case-crossover studies [26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63] and 48 time-series studies [64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111] were included in our final analysis. Study characteristics are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. The majority of case-crossover studies, n = 27 (71%), and time-series studies, n = 26 (54%), were conducted in Europe or North America and most, n = 62 of 86 total (72%), were based on single cities. Almost all studies, n = 84 (98%), employed monitoring (vs. modelling) as the source of exposure data, and most, n = 70 (81%), employed 24 h average concentration as the exposure metric. Most studies, n = 72 (84%), were based in whole or in part on hospital admission data. MI was the most commonly evaluated outcome, n = 55 studies (64%), and 14 studies (16%) examined subtypes (ST-elevation or transmural vs. Non-ST elevation). Thirty seven studies (43%) were mostly conducted prior to 2000 (majority of study duration prior to 2000) while 49 (57%) were conducted mostly post 2000. In total, analyses in the included studies were based on over 3.2 million events (the actual total is larger, but not all studies reported the number of events), and the number of events in individual studies ranged from 53 to 630,116.

Risk of bias ratings are summarized in Fig. 2, criteria are detailed in Additional File 2, and reasons for assigned ratings of risk of bias greater than low risk (or unable to assess) for individual studies are provided in Additional File 3. The greatest variability in ratings occurred in the exposure assessment and confounding domains, while ratings in the other domains (outcome assessment, completeness of outcome data, selective outcome reporting, conflict of interest, other sources of bias) were generally low or probably low risk of bias. Eighteen studies (20.9%) were rated probably high or high risk of bias or unable to assess in the exposure assessment domain because they relied on a single monitor, there was evidence of a mediocre correlation of modelled or measured values with ground measurements in the target community, or there was insufficient information. Forty studies (46.5%) were rated probably high or high risk of bias or unable to assess in the confounding domain because of lack of justification for covariate specification, employment of non-parametric smoothing functions associated with known biases [112, 113], unidirectional referent selection in case-crossover studies [22], or failure to describe covariate specification.

Effect estimates and pooled effect estimates

All 189 extracted risk estimates from individual studies, including from single and multi-pollutant models, and by population and outcome subgroup are provided in forest plots by region in Additional Files 4-7. Of these, we excluded estimates from pooling if they pertained to a single season, were superseded by other studies encompassing the same geographic area or time frame e.g. in subsequent multi-city studies or those spanning a longer study duration, leaving 67 studies(28 case-crossover and 39 time-series) included in the meta-analysis. Forest plots of odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals based on single pollutant models from case-crossover studies, by region and overall, are shown in Fig. 3. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals on pooled estimates by region and overall excluded 1 or no effect (i.e. they were statistically significant). The pooled estimate for European and North American studies was lower than that for studies from other areas, and the difference was statistically significant (p = 0.019) (see Table 3). Heterogeneity was lower for European and North American studies (I2 = 68.4%) than for studies from other regions (I2 = 91.4%). Forest plots of relative risks and 95% confidence intervals based on single pollutant models from time-series studies, by region and overall, are shown in Fig. 4. Again, 95% confidence intervals on pooled estimates by region and overall excluded 1 or no effect, although the magnitude of effects was smaller than for case-crossover studies. Heterogeneity was uniformly high. The pooled estimate for European and North American studies was lower than that for studies from other areas, but the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.40) (see Table 3). Pooled estimates were not sensitive to pooling estimator (REML vs. Dersimonian and Laird vs. Empirical Bayes) (Additional File 8), or to individual studies based on Leave One Out analysis (Additional File 9). Begg’s test of funnel plot asymmetry was not significant for either case-crossover or time-series studies, while Egger’s test indicated significant asymmetry for time-series studies (p = 0.002). Application of trim and fill (employing the L0 estimator [114]) to case-crossover studies was indicative of publication bias, suggesting that there were 11 missing studies with effect estimates less than the pooled estimate (Fig. 5). Filling in these studies was estimated to substantially reduce the overall pooled estimate for case-crossover studies from 1.074 (95%CI 1.052–1.097) to 1.044 (95% CI 1.017–1.070) per 10 ppb. Similarly, application of trim and fill to time-series studies suggested that there were 7 missing studies with effect estimates less than the pooled estimate. Filling in these studies was estimated to slightly reduce the overall pooled estimate for time-series studies from 1.022 (95%CI 1.016–1.029) to 1.019 (95%CI 1.012–1.026) per 10 ppb. See Additional File 10 for Funnel plot of time-series studies.

Relative risks from single pollutant models from individual time-series studies and pooled estimates by region (AMI, acute myocardial infarction, AP, angina pectoris, IHD, ischemic heart disease, STEMI, ST-elevation MI, EV, emergency visit, HA, hospital admission, MD, physician visit, lag reported in days)

Funnel plot of log (Odds Ratio) vs. standard error for case-crossover studies from Fig. 3. Filled circles represent observed values, open circles represent missing studies identified with trim and fill, and the vertical line represents the log of the pooled odds ratio. In the absence of publication bias, points should be symmetrically distributed around the vertical line, with smaller studies (larger standard errors on vertical axis) more widely scattered. Filling the plot with points mirroring observed values corrects for apparently missing smaller and/or negative studies which may have been suppressed due to publication bias

Meta-regression

Meta-regression revealed that the magnitude of the log odds ratio from case-crossover studies was significantly positively associated with study mean NO2 exposure (p = 0.042), as well as region other than North America or Europe (p = 0.033; there was no significant difference between North America and Europe), and timing of study primarily post 2000 (p = 0.031). When considered jointly, only region remained a nearly significant predictor (p = 0.057). Log relative risks from time-series studies were negatively associated with study mean NO2 (p = 0.041). Risk of bias in the exposure assessment and confounding domains, outcome (hospital admission vs. other), diagnosis (MI vs other), study interquartile range, standard deviation and range of NO2 were not significant predictors of the magnitude of effect for either case-crossover or time-series studies. Residual heterogeneity remained relatively high (I2 generally > 70%) even after accounting for significant predictor variables for both case-crossover and time-series studies.

Single vs. multi-pollutant models and subgroup analyses

Forest plots of paired estimates of effects from single and multi-pollutant models from the same study are shown in Figs. 6 and 7. Pooled estimates from single pollutant models were higher than those from multi-pollutant models and the confidence interval for multi-pollutant pooled estimates overlapped 1 or no effect. However, the difference between pooled estimates for single and multi-pollutant models was not significant (see Table 3).

Subgroup analyses are summarized in Table 3 in comparison to primary results. Pooled effect estimates were larger in older populations (generally ≥65 years, but in some cases ≥55 years or ≥ 75 years) in contrast to pooled estimates for younger populations for both case-crossover and time-series studies. However, differences between pooled estimates were not significant. No significant differences were observed by sex.

Shape of exposure-response relationship

Thirteen studies evaluated the shape of the exposure-response relationship between NO2 and IHD morbidity by examining the association by quantile of NO2 [43, 48, 50, 110], plotting the association using a non-linear function of NO2 [76, 80, 94, 98, 103, 106, 107, 111], or testing the significance of the difference between linear and non-linear models [41]. Of these, eight studies found a linear association [41, 43, 50, 80, 94, 98, 106, 107], in some instances only in subsets of the data by age [50] or season [80], while three found evidence of a threshold [76, 103, 110], although the available evidence is insufficient to identify a precise threshold value. Two studies reported no association between NO2 and MI risk, based on analysis by quantiles [48], and a plot using a non-linear function of NO2 [111]. An additional case-crossover study not included in pooled estimates because it characterized exposure using fixed increment/decrement thresholds rather than a linear term, found an apparently linear association between rapid changes in NO2 concentration and odds of MI [115].

Discussion

Based on an analysis of 67 case-crossover and time-series studies, we found that short term exposure to NO2 was significantly associated with IHD morbidity (pooled OR from case-crossover studies: 1.074 95% CI 1.052–1.097; pooled RR from time-series studies: 1.022 95% CI 1.016–1.029 per 10 ppb). There was evidence of publication bias particularly for case-crossover studies. Pooled estimates based on both types of studies were characterized by a high degree of heterogeneity. For case crossover studies, heterogeneity was only partially accounted for by study region (larger magnitude of effect outside Europe and North America), mean exposure (larger magnitude of effect at higher mean exposure), and age of study (larger magnitude of effect in newer studies), although when these factors were considered jointly, only study region was associated with magnitude of effect. Similarly, for time-series studies, heterogeneity was only partially accounted for by study mean NO2 (lower magnitude of effect with increasing mean). While risk of bias due to exposure assessment and confounding were not associated with magnitude of effect, residual heterogeneity could nonetheless be attributable to these factors, since we had only categorical ratings rather than precisely quantified measures of these factors. It is well documented, for example, that exposure measurement error is related to observed magnitude of effect, depending on type of error (classical or Berkson’s) [116,117,118]. Case-crossover and time-series studies are not confounded by risk factors related to individual characteristics which are stable over short time periods, as these are controlled for by design. Confounding by time is controlled for by design in case-crossover studies and by analysis in time-series studies, while confounding by time-varying factors such as weather, other pollutants and influenza epidemics is adjusted for in the analysis in both types of studies. We accounted for these factors through our assessment of risk of bias, and consideration of results from single and multi-pollutant models. We could not account for residual confounding by concomitant exposures to noise or stress which could be associated with both NO2 exposure and triggering of IHD morbidity, as these were not assessed in the primary studies we evaluated. Peters et al. [47, 119] collected data on time spent in traffic prior to MI onset and found that it was significantly associated with MI, but did not report joint models including both this variable and NO2 exposure. Pooled estimates based on multi-pollutant models were smaller than those from single pollutant models for both case-crossover and time-series studies, although these differences were not statistically significant. Pooled estimates based on older populations were also larger than those based on younger populations for both case-crossover and time-series studies, but again these differences were not statistically significant.

Our results are generally consistent with those of Mustafic et al., who included 21 studies in their meta-analysis and reported a pooled estimate of 1.011 (95% CI 1.006–1.016) per 10 μg/m3 NO2, with an I2 of 71% [9]. This is comparable to our pooled estimate for time-series studies (after converting to ppb), but smaller than that for case-crossover studies. Owing to the smaller number of studies, they were not able to evaluate results from single and multi-pollutant models, or for subgroups based on region, age, or sex, nor did they conduct meta-regression. We also note some inconsistencies in their analysis, notably the inclusion of results for mortality from all cardiovascular causes (not strictly IHD) from Hoek et al. [120], as well as errors - assigning identical results to Peters et al. [47] and Ruidavets et al. [48], and including a negative result from Stieb et al. [66], which was not reported by the authors of that study. Our pooled relative risk for time-series studies was also comparable to that of Mills et al. [10] (after converting to ppb), who reported a pooled relative risk of 1.0086 (95% CI 1.0052–1.012) per 10 μg/m3 based on results from 10 studies (separate pooled estimates were provided for an additional 11 studies of elderly populations). Limitations of Mills et al.’s review include limited evaluation of sources of heterogeneity or consideration of results from single vs. multi-pollutant models, and failure to assess risk of bias across multiple domains (adjustment for “important confounders” was an inclusion criterion). Other systematic reviews and meta-analyses of the short term association of PM2.5 and PM10 and IHD morbidity reported pooled effect estimates of comparable magnitude [11, 12].

Other lines of evidence

We have not conducted a systemic review of toxicological and human clinical evidence. However, in order to inform our conclusions about the existence of a causal association between short term NO2 exposure and IHD morbidity, we present a brief summary of evidence evaluating possible pathophysiological mechanisms which could explain the associations observed in epidemiological studies. While the evidence specifically linking NO2 to adverse cardiovascular effects in controlled animal toxicological studies is limited, some studies have identified adverse cardiovascular effects specifically from NO2 exposure, including increased blood viscosity, red cell rigidity and red cell aggregation after one and 3 months exposure [121], and endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress and inflammation following 7 day exposure [122]. With respect to effects of mixtures, Selikop et al. reported increased atherosclerosis response indicators (endothelin-1, matrix metalloproteinase-9, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-2, thiobarbituric acid reactive substances) attributed to NO2 following 50 day exposure to diesel or gasoline exhaust [123], Zhang et al. reported that co-exposure to NO2, SO2 and PM10 for 28 days resulted in endothelial dysfunction, increased inflammatory response, decreased blood pressure and increased heart rate [124], and Mauderly et al. found that a five gas mixture of NO2, SO2, CO, NO and NH3 for 50 days resulted in increases in endothelin-1, matrix metalloproteinase-9, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-2, heme oxygenase-1 and thiobarbituric acid reactive substances [125]. Studies have also noted persistent adverse effects of diesel emissions after particle filtration [126, 127], potentially implicating gaseous phase emissions, including NO2.

Controlled human exposure studies have produced mixed results. Scaife et al. reported no association between NO2 exposure and heart rate, heat rate variability (HRV), ectopic beats, or arrhythmias in adults with stable IHD [128], while Huang et al. reported significant associations with HRV in healthy young adults [129]. Riedl et al. found no association with coagulation factors, blood pressure, oxygen saturation or cardiovascular symptom scores in individuals with mild asthma [130] and Langrish et al. reported no significant associations with measures of fibrinolytic function in healthy males [131]. In an in-vitro study, Channell et al. found that exposure to plasma from healthy volunteers exposed to NO2 was associated with increased concentrations of intracellular and vascular cell adhesion molecules in human coronary artery endothelial cells [132]. Both Frampton et al. and Posin et al. reported reduced haemoglobin and hematocrit following NO2 exposure in healthy adults [133, 134], while Langrish et al. did not [131].

Overall rating of quality and strength of evidence

In their 2016 Science Assessments, both the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and Health Canada concluded that the evidence was suggestive of, but not sufficient to infer, a causal association between NO2 and IHD morbidity, based on a smaller number of studies, and fewer examining the impact of adjustment for co-pollutants than considered here, as well as limited and inconsistent supporting mechanistic evidence from controlled human and animal studies [1, 2]. Our observation that short term exposure to NO2 was significantly associated with IHD morbidity based on pooled ORs and RRs from a much larger number of case-crossover and time series studies, the majority of which were rated low or probably low risk of bias across most domains, provides good evidence that short term exposure to air pollution in general and particularly traffic related air pollution triggers IHD morbidity. With respect to the probability of a causal relationship specifically with NO2, following the Navigation Guide methodology [135] and the causality determination framework used by the US EPA/Health Canada [2] (Additional Files 11, 12), the significant heterogeneity among studies even after accounting for sources of heterogeneity, the relatively large proportion of studies (46.5%) rated as probably high or high risk of bias due to confounding by temporal cycles and weather, evidence of confounding related to other pollutants, inability to assess confounding from concomitant traffic-related exposures including noise and stress, and apparent publication bias affecting case-crossover studies, are considered downgrading factors in interpreting the overall strength of evidence. In total, 15 case-crossover and time-series studies provided estimates based on both single and multi-pollutant models. Multi-pollutant models should be interpreted with caution in that the sensitivity of the effect of one pollutant to inclusion of other pollutants in a joint model is affected by factors such as the correlation among pollutants and their relative degree of exposure measurement error [136]. Nonetheless, although pooled estimates based on multi-pollutant models were smaller in magnitude than from single pollutant models, the differences between pooled estimates were not statistically significant. Thus, while effects of NO2 appear to be confounded by co-pollutants, there is still evidence of an association after accounting for this. In a recent causal-modelling analysis of NO2, PM2.5 and mortality in 135 US cities, Schwartz et al. concluded that NO2 was independently associated with mortality, although residual confounding by other pollutants could not be ruled out [7]. Similarly, in their systematic review and meta-analysis attempting to distinguish effects of particulate matter and NO2 on mortality and hospital admissions in time-series studies, Mills et al. concluded that effects of NO2 were generally robust to inclusion of particulate matter measures in multi-pollutant models, strengthening the case for a causal relationship [137]. However, their analysis included only five studies of cardiac hospital admissions (not specifically IHD), and they could not rule out residual confounding by primary combustion particles [137]. While in the present review, accounting for publication bias affecting case-crossover studies reduced the magnitude of the pooled OR, the 95% CI still excluded 1 or no effect. In contrast to these downgrading factors, characterization of the exposure response relationship as linear or linear with a threshold in 11 of the 13 studies in which this was evaluated, is considered an upgrading factor, albeit based on a small number of studies. We therefore conclude that the epidemiological evidence suggests that there is a likely causal relationship between short term NO2 exposure and IHD morbidity, but important uncertainties remain, particularly related to the contribution of co-pollutants or other concomitant exposures, and the relative lack of supporting evidence from toxicological and controlled human studies. Upgrading to a conclusion that there is sufficient evidence for a causal association would require more conclusive evidence ruling out potential confounders as well as consistent supporting animal toxicological and human clinical evidence. Our conclusion parallels that of Health Canada in its determination that there is a likely causal relationship between short term exposure to NO2 and mortality [2], with similar caveats regarding potential confounding and a lack of supporting mechanistic evidence. USEPA differed in its assessment, concluding that the evidence is suggestive of, but not sufficient to infer, a causal relationship between short-term NO2 exposure and mortality [1]. Future time-series and case-crossover studies could address uncertainties related to confounding by co-pollutants by consistently examining effects in multi-pollutant models, recognizing the caveats noted earlier. Since few of the studies we reviewed addressed the shape of the concentration-response relationship, further examination in future studies would also be informative. Novel designs are needed to address other potential traffic-related confounders such as noise and stress. Finally, in order to facilitate evaluation of risk of bias, we recommend greater transparency in reporting on exposure assessment, particularly with respect to the number of ground monitors providing exposure data and proportion of days with missing data, and on specification of covariates in regression models. Consistent reporting of effects based on 24 h average concentrations (in addition to other metrics if desired) would obviate the need to convert effect size estimates from other metrics based on assumptions about the relative magnitude of effect.

Conclusions

We conducted a synthesis of the evidence from 86 case-crossover and time-series studies examining the association between NO2 and IHD morbidity, including sensitivity analyses based on pooling method, leave one out analysis and trim and fill, as well as subgroup analyses and/or meta-regression of single vs. multi-pollutant models and effects of region, age of study, study exposure levels, risk of bias ratings, age and sex. We concluded that there is a likely causal relationship between short term NO2 exposure and morbidity from ischemic heart disease, but important uncertainties remain, particularly related to the contribution of co-pollutants or other concomitant exposures, and the limited supporting evidence from animal toxicological studies and controlled human exposure studies.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Change history

24 July 2020

An amendment to this paper has been published and can be accessed via the original article.

Abbreviations

- AMI:

-

Acute myocardial infarction

- AP:

-

Angina pectoris

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CO:

-

Carbon monoxide

- EPA:

-

Environmental protection agency

- EV:

-

Emergency visit

- HA:

-

Hospital admission

- HRV:

-

Heart rate variability

- ICD:

-

International classification of diseases

- IHD:

-

Ischemic heart disease

- MD:

-

Physician visit

- MI:

-

Myocardial infarction

- NO2 :

-

Nitrogen dioxide

- NSTEMI:

-

Non-ST elevation myocardial infarction

- O3 :

-

Ozone

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- PAF:

-

Population attributable fraction

- PM2.5 :

-

Particulate matter with median aerodynamic diameter < 2.5 μm

- PM10 :

-

Particulate matter with median aerodynamic diameter < 10 μm

- PRESS:

-

Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses

- REML:

-

Restricted maximum likelihood

- RR:

-

Relative risk

- SO2:

-

Sulphur dioxide

- STEMI:

-

ST elevation myocardial infarction

References

USEPA. Integrated Science Assessment for Oxides of Nitrogen— Health Criteria. In: Research Triangle Park. North Carolina: US EPA; 2016. Report No.: EPA/600/R-15/068.

Canada H. Human health risk assessment for ambient nitrogen dioxide. Health Canada: Ottawa, Canada; 2016.

Geddes JA, Martin RV, Boys BL, van Donkelaar A. Long-term trends worldwide in ambient NO 2 concentrations inferred from satellite observations. Environ Health Perspect. 2016;124:281–9.

Nowbar AN, Gitto M, Howard JP, Francis DP, Al-Lamee R. Mortality from ischemic heart disease: analysis of data from the World Health Organization and coronary artery disease risk factors from NCD risk factor collaboration. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2019;12:e005375.

Nawrot TS, Perez L, Künzli N, Munters E, Nemery B. Public health importance of triggers of myocardial infarction: a comparative risk assessment. Lancet. 2011;377:732–40.

Brook JR, Burnett RT, Dann TF, Cakmak S, Goldberg MS, Fan X, et al. Further interpretation of the acute effect of nitrogen dioxide observed in Canadian time-series studies. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2007;17:S36–44.

Schwartz J, Fong K, Zanobetti A. A national multicity analysis of the causal effect of local pollution, no2, and pm2.5 on mortality. Environ Health Perspect. 2018;126:087004.

Brook RD, Rajagopalan S, Pope CA, Brook JR, Bhatnagar A, Diez-Roux AV, et al. Particulate matter air pollution and cardiovascular disease: an update to the scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;121:2331–78.

Mustafic H, Jabre P, Caussin C, Murad MH, Escolano S, Tafflet M, et al. Main air pollutants and myocardial infarction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2012;307:713–21.

Mills IC, Atkinson RW, Kang S, Walton H, Anderson HR. Quantitative systematic review of the associations between short-term exposure to nitrogen dioxide and mortality and hospital admissions. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e006946.

Cai X, Li Z, Scott EM, Li X, Tang M. Short-term effects of atmospheric particulate matter on myocardial infarction: a cumulative meta-analysis. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2016;23:6139–48.

Luo C, Zhu X, Yao C, Hou L, Zhang J, Cao J, et al. Short-term exposure to particulate air pollution and risk of myocardial infarction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2015;22:14651–62.

McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, Cogo E, Foerster V, Lefebvre C. PRESS peer review of electronic search strategies: 2015 guideline statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;75:40–6.

Stieb D, Lyrette N, Lavigne E, Hocking R, Zheng C, Salama D, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of effects of outdoor nitrogen dioxide: short term exposure and cardio-respiratory morbidity and long term exposure and mortality [Internet]. PROSPERO Int Prospect Regist Syst Rev. 2018; Available from: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php? RecordID=84497..

Health Canada. Investigating human exposure to contaminants in the environment: a handbook for exposure calculations. [Internet]. Ottawa: Health Canada; 1995 [cited 2019 Nov 5]. Available from: http://publications.gc.ca/Collection/H49-96-1-1995E-1.pdf.

Mitchell M, Muftakhidinov B, Winchen T. Engauge Digitizer Software [Internet]. Available from: http://markummitchell.github.io/engauge-digitizer.

Lam J, Sutton P, Kalkbrenner A, Windham G, Halladay A, Koustas E, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of multiple airborne pollutants and autism spectrum disorder. Kesavachandran CN, editor. Plos One. 2016;11:e0161851.

Moore E, Chatzidiakou L, Kuku M-O, Jones RL, Smeeth L, Beevers S, et al. Global associations between air pollutants and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease hospitalizations: a systematic review. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13:1814–27.

Song X, Liu Y, Hu Y, Zhao X, Tian J, Ding G, et al. Short-term exposure to air pollution and cardiac arrhythmia: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13:642.

Shah ASV, Lee KK, McAllister DA, Hunter A, Nair H, Whiteley W, et al. Short term exposure to air pollution and stroke: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2015;350:h1295.

Bhaskaran K, Gasparrini A, Hajat S, Smeeth L, Armstrong B. Time series regression studies in environmental epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42:1187–95.

Janes H, Sheppard L, Lumley T. Case-crossover analyses of air pollution exposure data: referent selection strategies and their implications for bias. Epidemiology. 2005;16:717–26.

Lu Y, Zeger SL. On the equivalence of case-crossover and time series methods in environmental epidemiology. Biostatistics. 2007;8:337–44.

Viechtbauer W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J Stat Softw. 2010;36:1–48.

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing [Internet]. R Found. Stat. Comput. 2019 [cited 2019 Oct 28]. Available from: https://www.R-project.org/.

Wang X, Kindzierski W, Kaul P. Comparison of transient associations of air pollution and AMI hospitalisation in two cities of Alberta, Canada, using a case-crossover design. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e009169.

Wang X, Kindzierski W, Kaul P. Air pollution and acute myocardial infarction hospital admission in Alberta, Canada: a three-step procedure case-crossover study. Plos One. 2015;10:e0132769.

Weichenthal S, Lavigne E, Evans G, Pollitt K, Burnett RT. Ambient PM2.5 and risk of emergency room visits for myocardial infarction: impact of regional PM2.5 oxidative potential: a case-crossover study. Environ Health. 2016;15.

Weichenthal S, Lavigne E, Villeneuve PJ, Reeves F. Airborne pollen concentrations and emergency room visits for myocardial infarction: a multicity case-crossover study in Ontario, Canada. Am J Epidemiol. 2016;183:613–21.

Basu R, Pearson D, Malig B, Broadwin R, Green R. The effect of high ambient temperature on emergency room visits. Epidemiology. 2012;23:813–20.

Evans KA, Hopke PK, Utell MJ, Kane C, Thurston SW, Ling FS, et al. Triggering of ST-elevation myocardial infarction by ambient wood smoke and other particulate and gaseous pollutants. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2017;27:198–206.

Peel J, Metzger K, Klein M, Flanders W, Mulholland J, Tolbert P. Ambient air pollution and cardiovascular emergency department visits in potentially sensitive groups. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165:625–33.

Peters A, Dockery DW, Muller JE, Mittleman MA. Increased particulate air pollution and the triggering of myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2001;103:2810–5.

Rich DQ, Kipen HM, Zhang J, Kamat L, Wilson AC, Kostis JB, et al. Triggering of Transmural infarctions, but not Nontransmural infarctions, by ambient fine particles. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118:1229–34.

Zanobetti A, Schwartz J. Air pollution and emergency admissions in Boston, MA. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60:890–5.

Argacha JF, Collart P, Wauters A, Kayaert P, Lochy S, Schoors D, et al. Air pollution and ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a case-crossover study of the Belgian STEMI registry 2009–2013. Int J Cardiol. 2016;223:300–5.

Bard D, Kihal W, Schillinger C, Fermanian C, Ségala C, Glorion S, et al. Traffic-related air pollution and the onset of myocardial infarction: disclosing benzene as a trigger? a small-area case-crossover study. Cormier SA, editor. PLoS One. 2014;9:e100307.

Berglind N, Ljungman P, Möller J, Hallqvist J, Nyberg F, Rosenqvist M, et al. Air pollution exposure—a trigger for myocardial infarction? Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2010;7:1486–99.

Bhaskaran K, Hajat S, Armstrong B, Haines A, Herrett E, Wilkinson P, et al. The effects of hourly differences in air pollution on the risk of myocardial infarction: case crossover analysis of the MINAP database. BMJ Online. 2011;343:d5531.

Buszman PE, Derbisz K, Kwasiborski P, Chrzaszcz P, Mularska M, Baron D, et al. Impact of air pollution on hospital patients admitted with ST- and non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in heavily polluted cities within the European Union. Cardiol J. 2018.

Butland BK, Atkinson RW, Milojevic A, Heal MR, Doherty RM, Armstrong BG, et al. Myocardial infarction, ST-elevation and non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction and modelled daily pollution concentrations: a case-crossover analysis of MINAP data. Open Heart. 2016;3:e000429.

Collart P, Coppieters Y, Mercier G, Massamba Kubuta V, Leveque A. Comparison of four case-crossover study designs to analyze the association between air pollution exposure and acute myocardial infarction. Int J Environ Health Res. 2015;25:601–13.

D’Ippoliti D, Forastiere F, Ancona C. Nera Agabiti, Danilo Fusco, Paola Michelozzi, et al. air pollution and myocardial infarction in Rome: a case-crossover analysis. Epidemiology. 2003;14:528–35.

Milojevic A, Wilkinson P, Armstrong B, Bhaskaran K, Smeeth L, Hajat S. Short-term effects of air pollution on a range of cardiovascular events in England and Wales: case-crossover analysis of the MINAP database, hospital admissions and mortality. Heart. 2014;100:1093–8.

Nuvolone D, Balzi D, Chini M, Scala D, Giovannini F, Barchielli A. Short-term association between ambient air pollution and risk of hospitalization for acute myocardial infarction: results of the cardiovascular risk and air pollution in Tuscany (RISCAT) study. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;174:63–71.

Panasevich S, Leander K, Ljungman P, Bellander T, de Faire U, Pershagen G, et al. Interaction between air pollution exposure and genes in relation to levels of inflammatory markers and risk of myocardial infarction. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e003058.

Peters A, von Klot S, Heier M, Trentinaglia I, Cyrys J, Hormann A, et al. Part I. Air Pollution, Personal Activities, and Onset of Myocardial Infarction in a Case–Crossover Study. In: Part Air Pollut Nonfatal Card Events. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Health Effects Institute; 2005. p. 1–79.

Ruidavets J-B. Ozone air pollution is associated with acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2005;111:563–9.

Sahlén A, Ljungman P, Erlinge D, Chan MY, Yap J, Hausenloy DJ, et al. Air pollution in relation to very short-term risk of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: case-crossover analysis of SWEDEHEART. Int J Cardiol. 2019;275:26–30.

Vencloviene J, Grazuleviciene R, Babarskiene R, Dedele A, Grazulevicius T. Short-term nitrogen dioxide exposure and geomagnetic activity interaction: contribution to emergency hospitalization for acute coronary syndrome. Int J Environ Health Res. 2011;21:149–60.

Wichmann J, Ketzel M, Ellermann T, Loft S. Apparent temperature and acute myocardial infarction hospital admissions in Copenhagen, Denmark: a case-crossover study. Environ Health. 2012;11.

Wichmann J. Annika Rosengren, Karin Sjoberg, Lars Barregard, Gerd Sallsten. Association between ambient temperature and acute myocardial infarction hospitalisations in Gothenburg, Sweden: 1985-2010. PLoS One. 2013;8:e62059.

Akbarzadeh MA, Khaheshi I, Sharifi A, Yousefi N, Naderian M, Namazi MH, et al. The association between exposure to air pollutants including PM 10 , PM 2.5 , ozone, carbon monoxide, sulfur dioxide, and nitrogen dioxide concentration and the relative risk of developing STEMI: A case-crossover design. Environ Res. 2018;161:299–303.

Barnett AG, Williams GM, Schwartz J, Best TL, Neller AH, Petroeschevsky AL, et al. The effects of air pollution on hospitalizations for cardiovascular Diseasein elderly people in Australian and New Zealand cities. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114:1018–23.

Cheng M-F, Tsai S-S, Yang C-Y. Air pollution and hospital admissions for myocardial infarction in a Tropical City: Kaohsiung, Taiwan. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2009;72:1135–40.

Franck U, Leitte AM, Suppan P. Multiple exposures to airborne pollutants and hospital admissions due to diseases of the circulatory system in Santiago de Chile. Sci Total Environ. 2014;468–469:746–56.

Hsieh Y-L, Yang Y-H, Wu T-N, Yang C-Y. Air pollution and hospital admissions for myocardial infarction in a Subtropical City: Taipei, Taiwan. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2010;73:757–65.

Huang C-H, Chao D-Y, Wu C-C, Hsu S-Y, Soon M-S, Chang C-C, et al. Influenza vaccination and the endurance against air pollution among elderly with acute coronary syndrome. Vaccine. 2016;34:6316–22.

Kojima S, Michikawa T, Ueda K, Sakamoto T, Matsui K, Kojima T, et al. Asian dust exposure triggers acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2017;38:3202–8.

Li J, Liu C, Cheng Y, Guo S, Sun Q, Kan L, et al. Association between ambient particulate matter air pollution and ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a case-crossover study in a Chinese city. Chemosphere. 2019;219:724–9.

Liu H, Tian Y, Xiang X, Sun K, Juan J, Song J, et al. Air pollution and hospitalization for acute myocardial infarction in China. Am J Cardiol. 2017;120:753–8.

Tsai S-S, Chen P-S, Yang Y-H, Liou S-H, Wu T-N, Sung F-C, et al. Air pollution and hospital admissions for myocardial infarction: are there potentially sensitive groups? J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2012;75:242–51.

Turin TC, Kita Y, Rumana N, Nakamura Y, Ueda K, Takashima N, et al. Short-term exposure to air pollution and incidence of stroke and acute myocardial infarction in a Japanese population. Neuroepidemiology. 2012;38:84–92.

Burnett RT, Smith-Doiron M, Stieb D, Cakmak S, Brook JR. Effects of particulate and gaseous air pollution on cardiorespiratory hospitalizations. Arch Environ Health. 1999;54:130–9.

Stieb DM, Beveridge RC, Brook JR, Smith-Doiron M, Burnett RT, Dales RE, et al. Air pollution, aeroallergens and cardiorespiratory emergency department visits in Saint John, Canada. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol. 2000;10:461–77.

Stieb DM, Szyszkowicz M, Rowe BH, Leech JA. Air pollution and emergency department visits for cardiac and respiratory conditions: a multi-city time-series analysis. Environ Health. 2009;8.

Szyszkowicz M. Air pollution and emergency department visits for ischemic heart disease in Montreal, Canada. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2007;20:167–73.

Krall JR, Chang HH, Waller LA, Mulholland JA, Winquist A, Talbott EO, et al. A multicity study of air pollution and cardiorespiratory emergency department visits: comparing approaches for combining estimates across cities. Environ Int. 2018;120:312–20.

Linn WS, Szlachcic Y, Gong HJ, Kinney PL, Berhane KT. Air pollution and daily hospital admissions in metropolitan Los Angeles. Environ Health Perspect. 2000;108:427–34.

Lippmann M, Ito K, Nadas A, Burnett R. Association of Particulate Matter Components with Daily Mortality and Morbidity in Urban Populations. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Health Effects Institute; 2000. p. 5–72. Report No.: 95.

Mann JK, Tager IB, Lurmann F, Segal M, Quesenberry CP, Lugg MM, et al. Air pollution and hospital admissions for ischemic heart disease in persons with congestive heart failure or arrhythmia. Environ Health Perspect. 2002;110:1247–52.

Metzger KB, Tolbert PE. Klein M, Peel JL, Flanders WD, Knox Todd, et al. ambient air pollution and cardiovascular emergency department visits. Epidemiology. 2004;15:46–56.

Pearce JL, Neelon B, Bozigar M, Hunt KJ, Commodore A, Vena J. Associations between multipollutant day types and select cardiorespiratory outcomes in Columbia, South Carolina, 2002 to 2013. Environ Epidemiol. 2018;2:e030.

Sarnat SE, Winquist A, Schauer JJ, Turner JR, Sarnat JA. Fine particulate matter components and emergency department visits for cardiovascular and respiratory diseases in the St. Louis, Missouri–Illinois, metropolitan area. Environ Health Perspect. 2015;123:437–44.

Anderson H, Bremner S, Atkinson R, Harrison R, Walters S. Particulate matter and daily mortality and hospital admissions in the west midlands conurbation of the United Kingdom: associations with fine and coarse particles, black smoke and sulphate. Occup Environ Med. 2001;58:504–10.

Atkinson RW, Bremner SA, Anderson HR, Strachan DP, Bland JM. Ponce de Leon a. short-term associations between emergency hospital admissions for respiratory and cardiovascular disease and outdoor air pollution in London. Arch Environ Health. 1999;54:398–411.

Baneras J, Ferreira-Gonzalez I, Marsal JR, Barrabes JA, Ribera A, Lidon RM, et al. Short-term exposure to air pollutants increases the risk of ST elevation myocardial infarction and of infarct-related ventricular arrhythmias and mortality. Int J Cardiol. 2018;250:35–42.

Caussin C, Escolano S, Mustafic H, Bataille S, Tafflet M, Chatignoux E, et al. Short-term exposure to environmental parameters and onset of ST elevation myocardial infarction. The CARDIO-ARSIF registry. Int J Cardiol. 2015;183:17–23.

Collart P, Dubourg D, Levêque A, Sierra NB, Coppieters Y. Short-term effects of nitrogen dioxide on hospital admissions for cardiovascular disease in Wallonia, Belgium. Int J Cardiol. 2018;255:231–6.

Eilstein D, Quenel P, Hedelin G, Kleinpeter J, Arveiler D, Schaffer P. Air pollution and myocardial infarction. Strasbourg France, 1984-89. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique. 2001;49:13–25.

Halonen JI, Lanki T, Yli-Tuomi T, Tiittanen P, Kulmala M, Pekkanen J. Particulate air pollution and acute cardiorespiratory hospital admissions and mortality among the elderly. Epidemiol. 2009;20:143-53.

Konduracka E, Niewiara Ł, Guzik B, Kotynia M, Szolc P, Gajos G, et al. Effect of short-term fluctuations in outdoor air pollution on the number of hospital admissions due to acute myocardial infarction among inhabitants of Krakow, Poland. Pol Arch Intern Med. 2019;129:88–96.

Lanki T, Pekkanen J, Aalto P, Elosua R, Berglind N, D’Ippoliti D, et al. Associations of traffic related air pollutants with hospitalisation for first acute myocardial infarction: the HEAPSS study. Occup Environ Med. 2006;63:844–51.

Larrieu S, Jusot J-F, Blanchard M, Prouvost H, Declercq C, Fabre P, et al. Short term effects of air pollution on hospitalizations for cardiovascular diseases in eight French cities: the PSAS program. Sci Total Environ. 2007;387:105–12.

Le Tertre A, Medina S, Samoli E, Forsberg B, Michelozzi P, Boumghar A, et al. Short-term effects of particulate air pollution on cardiovascular diseases in eight European cities. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2002;56:773–9.

Medina S, Le Tertre A, Quénel P, Le Moullec Y, Lameloise P, Guzzo JC, et al. Air pollution and doctors’ house calls: results from the ERPURS system for monitoring the effects of air pollution on public health in greater Paris, France, 1991–1995. Environ Res. 1997;75:73–84.

Poloniecki JD, Atkinson RW. Leon e, Anderson HR. daily time series for cardiovascular hospital admissions and previous day’s air pollution in London, UK. Occup Environ Med. 1997;54:535–40.

Ponka A, Virtanen M. Low-level air pollution and hospital admissions for cardiac and cerebrovascular diseases in Helsinki. Am J Public Health. 1996;86:1273–80.

von Klot S. Ambient air pollution is associated with increased risk of hospital cardiac readmissions of myocardial infarction survivors in five European cities. Circulation. 2005;112:3073–9.

Bell ML, Levy JK, Lin Z. The effect of sandstorms and air pollution on cause-specific hospital admissions in Taipei, Taiwan. Occup Environ Med. 2008;65:104–11.

Cendon S, Pereira LAA, Braga ALF, Conceição GMS, Cury Junior A, Romaldini H, et al. Air pollution effects on myocardial infarction. Rev Saúde Pública. 2006;40:414–9.

Chen C, Wang X, Lv C, Li W, Ma D, Zhang Q, et al. The effect of air pollution on hospitalization of individuals with respiratory and cardiovascular diseases in Jinan, China. Medicine. 2019;98:e15634.

Ghaffari S, Hajizadeh R, Pourafkari L, Shokouhi B, Tajlil A, Mazani S, et al. Air pollution and admissions due to ST elevation myocardial infarction—a time-series study from northwest of Iran. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2017;24:27469–75.

Goggins WB, Chan EYY, Yang C-Y. Weather, pollution, and acute myocardial infarction in Hong Kong and Taiwan. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:243–9.

Hosseinpoor AR, Forouzanfar MH, Yunesian M, Asghari F, Naieni KH, Farhood D. Air pollution and hospitalization due to angina pectoris in Tehran, Iran: a time-series study. Environ Res. 2005;99:126–31.

Jalaludin B, Morgan G, Lincoln D, Sheppeard V, Simpson R, Corbett S. Associations between ambient air pollution and daily emergency department attendances for cardiovascular disease in the elderly (65 + years), Sydney, Australia. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2006;16:225–37.

Lee J-T, Kim H, Cho Y-S, Hong Y-C, Ha E-H, Park H. Air pollution and hospital admissions for ischemic heart diseases among individuals 64+ years of age residing in Seoul, Korea. Arch Environ Health Int J. 2003;58:617–23.

Phosri A, Ueda K, Phung VLH, Tawatsupa B, Honda A, Takano H. Effects of ambient air pollution on daily hospital admissions for respiratory and cardiovascular diseases in Bangkok, Thailand. Sci Total Environ. 2019;651:1144–53.

Pothirat C, Chaiwong W, Liwsrisakun C, Bumroongkit C, Deesomchok A, Theerakittikul T, et al. Acute effects of air pollutants on daily mortality and hospitalizations due to cardiovascular and respiratory diseases. J Thorac Dis. 2019;11:3070–83.

Qiu H, Yu IT, Wang X, Tian L, Tse LA, Wong TW. Cool and dry weather enhances the effects of air pollution on emergency IHD hospital admissions. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:500–5.

Simpson R, Williams G, Petroeschevsky A, Best T, Morgan G, Denison L, et al. The short-term effects of air pollution on hospital admissions in four Australian cities. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2005;29:213–21.

Soleimani Z, Darvishi Boloorani A, Khalifeh R, Griffin DW, Mesdaghinia A. Short-term effects of ambient air pollution and cardiovascular events in shiraz, Iran, 2009 to 2015. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2019;26:6359–67.

Tam W, Wong T, Wong A. Association between air pollution and daily mortality and hospital admission due to ischaemic heart diseases in Hong Kong. Atmos Environ. 2015;120:360–8.

Thach T-Q, Wong C-M, Chan K-P, Chau Y-K, Neil Thomas G, Ou C-Q, et al. Air pollutants and health outcomes: assessment of confounding by influenza. Atmos Environ. 2010;44:1437–42.

Wong TW, Lau TS, Yu TS, Neller A, Wong SL, Tam W, et al. Air pollution and hospital admissions for respiratory and cardiovascular diseases in Hong Kong. Occup Environ Med. 1999;56:679–83.

Wong C-M, Atkinson RW, Anderson HR, Hedley AJ, Ma S, Chau PY-K, et al. A tale of two cities: effects of air pollution on hospital admissions in Hong Kong and London compared. Environ Health Perspect. 2002;110:67–77.

Xie J, He M, Zhu W. Acute effects of outdoor air pollution on emergency department visits due to five clinical subtypes of coronary heart diseases in Shanghai, China. J Epidemiol. 2014;24:452–9.

Yamaji K, Kohsaka S, Morimoto T, Fujii K, Amano T, Uemura S, et al. Relation of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction to daily ambient temperature and air pollutant levels in a Japanese Nationwide percutaneous coronary intervention registry. Am J Cardiol. 2017;119:872–80.

Ye F, Piver WT, Ando M, Portier CJ. Effects of temperature and air pollutants on cardiovascular and respiratory diseases for males and females older than 65 years of age in Tokyo, July and august 1980–1995. Environ Health Perspect. 2001;109:5.

Yu IT, Qiu H, Wang X, Tian L, Tse LA. Synergy between particles and nitrogen dioxide on emergency hospital admissions for cardiac diseases in Hong Kong. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:2831–6.

Yu Y, Yao S, Dong H, Ji M, Chen Z, Li G, et al. Short-term effects of ambient air pollutants and myocardial infarction in Changzhou, China. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2018;25:22285–93.

Dominici F, McDermott A, Zeger SL, Samet JM. On the use of generalized additive models in time-series studies of air pollution and health. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:193–203.

Ramsay TO, Burnett RT, Krewski D. The effect of concurvity in generalized additive models linking mortality to ambient particulate matter. Epidemiology. 2003;14:18–23.

Duval S, Tweedie R. A nonparametric “trim and fill” method of accounting for publication Bias in meta-analysis. J Am Stat Assoc. 2000;95:89–98.

Rasche M, Walther M, Schiffner R, Kroegel N, Rupprecht S, Schlattmann P, et al. Rapid increases in nitrogen oxides are associated with acute myocardial infarction: a case-crossover study. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2018;25:1707–16.

Zeger SL, Thomas D, Dominici F, Samet JM, Schwartz J, Dockery D, et al. Exposure measurement error in time-series studies of air pollution: concepts and consequences. Environ Health Perspect. 2000;108:419–26.

Goldman GT, Mulholland JA, Russell AG, Strickland MJ, Klein M, Waller LA, et al. Impact of exposure measurement error in air pollution epidemiology: effect of error type in time-series studies. Environ Health Glob Access Sci Source. 2011;10:61.

Richmond-Bryant J, Long TC. Influence of exposure measurement errors on results from epidemiologic studies of different designs. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2019.

Peters A, von Klot S, Heier M, Trentinaglia I, Hormann A, Wichmann H, et al. Exposure to traffic and the onset of myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1721–30.

Hoek G, Brunekreef B, Verhoeff A, van Wijnen J, Fischer P. Daily mortality and air pollution in The Netherlands. J Air Waste Manag Assoc. 1995;2000(50):1380–9.

Zhu N, Li H, Han M, Guo L, Chen L, Yun Y, et al. Environmental nitrogen dioxide (NO2) exposure influences development and progression of ischemic stroke. Toxicol Lett. 2012;214:120–30.

Li H, Han M, Guo L, Li G, Sang N. Oxidative stress, endothelial dysfunction and inflammatory response in rat heart to NO2 inhalation exposure. Chemosphere. 2011;82:1589–96.

Seilkop SK, Campen MJ, Lund AK, McDonald JD, Mauderly JL. Identification of chemical components of combustion emissions that affect pro-atherosclerotic vascular responses in mice. Inhal Toxicol. 2012;24:270–87.

Zhang Y, Ji X, Ku T, Sang N. Inflammatory response and endothelial dysfunction in the hearts of mice co-exposed to SO 2 , NO 2 , and PM 2.5. Environ Toxicol. 2016;31:1996–2005.

Mauderly JL, Kracko D, Brower J, Doyle-Eisele M, McDonald JD, Lund AK, et al. The National Environmental Respiratory Center (NERC) experiment in multi-pollutant air quality health research: IV. Vascular effects of repeated inhalation exposure to a mixture of five inorganic gases. Inhal Toxicol. 2014;26:691–6.

Karoui A, Crochemore C, Mulder P, Preterre D, Cazier F, Dewaele D, et al. An integrated functional and transcriptomic analysis reveals that repeated exposure to diesel exhaust induces sustained mitochondrial and cardiac dysfunctions. Environ Pollut. 2019;246:518–26.

Karthikeyan S, Thomson EM, Kumarathasan P, Guénette J, Rosenblatt D, Chan T, et al. Nitrogen dioxide and ultrafine particles dominate the biological effects of inhaled diesel exhaust treated by a catalyzed diesel particulate filter. Toxicol Sci. 2013;135:437–50.

Scaife A, Barclay J, Hillis GS, Srinivasan J, Macdonald DW, Ross JAS, et al. Lack of effect of nitrogen dioxide exposure on heart rate variability in patients with stable coronary heart disease and impaired left ventricular systolic function. Occup Environ Med. 2012;69:587–91.

Huang Y-CT, Rappold AG, Graff DW, Ghio AJ, Devlin RB. Synergistic effects of exposure to concentrated ambient fine pollution particles and nitrogen dioxide in humans. Inhal Toxicol. 2012;24:790–7.

Riedl M, Diaz-Sanchez D, Linn W, Gong H, Clark K, Effros R, et al. Allergic inflammation in the human lower respiratory tract affected by exposure to diesel exhaust. Health Effects Institute: Cambridge, Massachusetts; 2012.

Langrish JP, Lundbäck M, Barath S, Söderberg S, Mills NL, Newby DE, et al. Exposure to nitrogen dioxide is not associated with vascular dysfunction in man. Inhal Toxicol. 2010;22:192–8.

Channell MM, Paffett ML, Devlin RB, Madden MC, Campen MJ. Circulating factors induce coronary endothelial cell activation following exposure to inhaled diesel exhaust and nitrogen dioxide in humans: evidence from a novel translational in vitro model. Toxicol Sci. 2012;127:179–86.

Frampton MW, Boscia J, Roberts NJ, Azadniv M, Torres A, Cox C, et al. Nitrogen dioxide exposure: effects on airway and blood cells. Am J Physiol-Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002;282:L155–65.

Posin C, Clark K, Jones MP, Patterson JV, Buckley RD, Hackney JD. Nitrogen dioxide inhalation and human blood biochemistry. Arch Environ Health Int J. 1978;33:318–24.

Lam J, Sutton P, McPartland J, Davidson L, Daniels N, Sen S, et al. Applying the navigation guide systematic review methodology case study #5 association between developmental exposures to pbdes and human neurodevelopment: Syst Rev Evid Protoc 2015 [Internet]. [cited 2019 Aug 18]. Available from: http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPEROFILES/17890_PROTOCOL_20150322.pdf.

Tolbert PE, Klein M, Peel JL, Sarnat SE, Sarnat JA. Multipollutant modeling issues in a study of ambient air quality and emergency department visits in Atlanta. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2007;17:S29–35.

Mills IC, Atkinson RW, Anderson HR, Maynard RL, Strachan DP. Distinguishing the associations between daily mortality and hospital admissions and nitrogen dioxide from those of particulate matter: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e010751.

Acknowledgements

We thank Lisa Glandon, MIS (Health Library, Health Canada) for peer review of the MEDLINE search strategy and Drs. Juleen Lam (University of California, San Francisco and California State University, East Bay), Richard Burnett (Health Canada), Hong Chen (Health Canada and University of Toronto), Mieczysław Szyszkowicz, (Health Canada), Paul Villeneuve (Carleton University) and Scott Weichenthal (McGill University) for their advice in adapting Navigation Guide risk of bias criteria for case-crossover and time-series studies. We also thank Drs. Ross Anderson, Richard Atkinson, Rupa Basu, Barbara Butland, Kazuhiko Ito, Alain Le Tertre, Daniela Nuvolone, Chaicharn Pothirat, Mieczysław Szyszkowicz, Tanvir Turin, and Janine Wichmann for responding to queries about their papers. Barry Jessiman and Benny Ling (Health Canada) provided helpful comments.

Funding

The study was funded by Health Canada, of which DMS, RH, NL, CM, EL and HHS are employees.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DMS conceived of and designed the study, contributed to data acquisition, and analyzed the data. CZ, DS and RH contributed to design of the study and acquisition of data. RB and ME contributed to data acquisition and analysis. NL, EL and HHS contributed to study design. All authors contributed to drafting the manuscript and reviewed and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original version of this article was revised: the last letter of the author name of Rania Berjawi has been updated.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.

Details of Search Strategies.

Additional file 2.

Summary of Risk of Bias Criteriaa.

Additional file 3.

Reasons for Risk of Bias Ratings > Low Risk.

Additional file 4.

Forest plot of case-crossover studies from Europe and North America (AMI, acute myocardial infarction, NSTEMI, non ST-elevation MI, STEMI, ST-elevation MI, EV, emergency visit, HA, hospital admission, T, temperature, Ox, total oxidants, GSH, glutathione related oxidative potential).

Additional file 5.

Forest plot of case-crossover studies outside Europe and North America (AMI, acute myocardial infarction, STEMI, ST-elevation MI, EV, emergency visit, HA, hospital admission, T, temperature).

Additional file 6.

Forest plot of time-series studies from Europe and North America (AMI, acute myocardial infarction, AP, angina pectoris, IHD, ischemic heart disease, STEMI, ST-elevation MI, EV, emergency visit, HA, hospital admission, MD, physician visit, lag reported in days).

Additional file 7.

Forest plot of time-series studies from outside Europe and North America (AMI, acute myocardial infarction, AP, angina pectoris, IHD, ischemic heart disease, STEMI, ST-elevation MI, EV, emergency visit, HA, hospital admission, lag reported in days).

Additional file 8.

Sensitivity analyses by estimator.

Additional file 9.

Leave one out analysis.

Additional file 10.

Funnel plot of log(Relative Risk) vs. standard error for time-series studies from Fig. 4. Filled circles represent observed values, open circles represent missing studies identified with trim and fill, and the vertical line represents the log of the pooled relative risk. In the absence of publication bias, points should be symmetrically distributed around the vertical line, with smaller studies (larger standard errors on vertical axis) more widely scattered. Filling the plot with points mirroring observed values corrects for apparently missing smaller and/or negative studies which may have been suppressed due to publication bias.

Additional file 11.

Navigation Guide Criteria for Overall Quality and Strength of Evidencea.

Additional file 12.

USEPA/Health Canada Criteria for Evaluating Likelihood of Causal Relationshipa.

Rights and permissions

, corrected publication 2020 Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Stieb, D.M., Zheng, C., Salama, D. et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of case-crossover and time-series studies of short term outdoor nitrogen dioxide exposure and ischemic heart disease morbidity. Environ Health 19, 47 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-020-00601-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-020-00601-1