Abstract

Background

2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) is a toxic environmental contaminant that can bioaccumulate in humans, cross the placenta, and cause immunological effects in children, including altering their risk of developing allergies. On July 10, 1976, a chemical explosion in Seveso, Italy, exposed nearby residents to a high amount of TCDD. In 1996, the Seveso Women’s Health Study (SWHS) was established to study the effects of TCDD on women’s health. Using data from the Seveso Second Generation Health Study, we aim to examine the effect of prenatal exposure to TCDD on the risk of atopic conditions in SWHS children born after the explosion.

Methods

Individual-level TCDD was measured in maternal serum collected soon after the accident. In 2014, we initiated the Seveso Second Generation Health Study to follow-up the children of the SWHS cohort who were born after the explosion or who were exposed in utero to TCDD. We enrolled 677 children, and cases of atopic conditions, including eczema, asthma, and hay fever, were identified by self-report during personal interviews with the mothers and children. Log-binomial and Poisson regressions were used to determine the association between prenatal TCDD and atopic conditions.

Results

A 10-fold increase in 1976 maternal serum TCDD (log10TCDD) was not significantly associated with asthma (adjusted relative risk (RR) = 0.93; 95% CI: 0.61, 1.40) or hay fever (adjusted RR = 0.99; 95% CI: 0.76, 1.27), but was significantly inversely associated with eczema (adjusted RR = 0.63; 95% CI: 0.40, 0.99). Maternal TCDD estimated at pregnancy was not significantly associated with eczema, asthma, or hay fever. There was no strong evidence of effect modification by child sex.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that maternal serum TCDD near the time of explosion is associated with lower risk of eczema, which supports other evidence pointing to the dysregulated immune effects of TCDD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Atopic conditions, including eczema, asthma, and hay fever, are one of the leading causes of chronic illness worldwide and are present in approximately 20% of the population [1]. The prevalence of atopic diseases has been increasing in the past few decades in both industrialized and developing countries [1]. One of the proposed reasons for this is increased exposure to environmental pollutants, as they can interfere with the immune system and subsequently alter the risk of developing allergy and asthma [2]. 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD), a toxic chemical compound and a widespread environment contaminant, is produced as a byproduct of chemical and industrial processes [2, 3]. Because TCDD is highly lipophilic and has a relatively long half-life in humans of 7–9 years, it can build up in the food chain and accumulate in human fat tissues [4]. This is hazardous because TCDD is a known human carcinogen and potent endocrine disruptor, and has been shown to be immunotoxic [5,6,7]. For example, a broad range of immunotoxic effects have been observed in animal studies, including suppression of humoral and cell-mediated immunity, impaired infection resistance, and potential increased allergic sensitization [8,9,10]. Furthermore, epidemiological studies have found that exposure to dioxin or dioxin-like compounds is associated with dysregulated immune responses related to inflammation and lower risk of developing atopic conditions [11,12,13,14,15].

TCDD can cross the placental barrier [16] and impact development of the fetus. Because the immune system develops extensively during the fetal period, this is a critical window of susceptibility to the effects of environmental exposures. In experimental studies, prenatal and perinatal exposure to TCDD suppresses immune function and exacerbates inflammatory conditions in the offspring [17,18,19]. However, research on the atopic effects of in utero exposure to TCDD in humans is scarce and inconsistent [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30]. For example, in a Danish birth cohort study, maternal serum levels of dioxin-like polychlorinated biphenyls (PCB-118) was associated with children’s risk of developing asthma [20], but not with allergic sensitization at 20 years of age [21]. In contrast, birth cohort studies in Spain and Slovakia did not find any associations in infants between dioxin-like PCBs in maternal serum and wheeze [24] and immunoglobulin E (IgE) levels [25], respectively. Overall, results from these studies are inconsistent, with some studies reporting decreased risks [22, 23, 27, 31] and others increased risk [20, 32].

Animal data also suggest that the immunomodulatory effects of prenatal exposure to TCDD may be sex-specific [19, 33]. However, few epidemiologic studies have examined sex differences in allergic conditions, and those that have showed inconsistent results. A study on Canadian pregnant women found no evidence of sex interaction between PCB-118 exposure and IgE levels in offspring [28]. In contrast, a study in a Japanese cohort of pregnant women found that dioxin concentrations in maternal blood were negatively associated with IgE levels in male infants, but not female infants [29]. When allergic conditions were examined in this cohort, there was a weak association with allergic symptoms in all infants, but the risk of infections was higher in males [30].

On July 10, 1976, a chemical plant explosion in Seveso, Italy, deposited approximately 30 kg of TCDD over the surrounding area, which was divided into exposure zones (A, B, and R) based on surface soil TCDD measurements. This accident caused one of the highest residential exposures to TCDD ever recorded [34]. A Seveso-based study found that TCDD levels in adult residents of highly contaminated and surrounding areas were negatively associated with immunoglobulin G (IgG) concentration, which suggests TCDD may play a role in suppressing antibody production [35]. In 1996, the Seveso Women’s Health Study (SWHS) was initiated to examine the effects of TCDD exposure on women’s health. SWHS is a historical cohort of women living in Seveso or nearby areas when the explosion occurred [36]. In 2014, the Seveso Second Generation Health Study was initiated to follow-up the children of the SWHS cohort who were born after the explosion or who were exposed in utero to TCDD [37].

The aim of this study is to investigate the relationship between prenatal exposure to TCDD and the risk of developing atopic conditions, including eczema, asthma, and hay fever, in the Seveso second generation cohort. We also aim to examine whether this relationship is modified by the sex of the child.

Methods

Study population

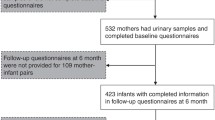

Details of the SWHS and the Seveso Second Generation Health Study are presented elsewhere [36, 37]. Briefly, from 1996 to 1998, participants were recruited from the female population residing in or near Seveso at the time of explosion. Women were eligible if they were 40 years old or younger, resided in the highest contaminated exposure zones (A and B) on July 10, 1976, and had archived sera collected soon after the explosion in which to measure TCDD. Of the eligible women, 981 (80%) agreed to participate. From 2014 to 2016, we conducted the Seveso Second Generation Health Study. Women from the SWHS cohort and their children born after the explosion were contacted. Eligible children included those who were born to the SWHS cohort after July 10, 1976 who were 2 years or older at follow-up. Of 950 children, 16 were deceased and 9 were less than 2 years old. Of the 925 eligible children, 677 children, 2 to 38 years of age and born to 438 mothers, were able to be reached and agreed to participate (73%). For the analysis, we excluded one child under 18 years whose mother was deceased and could not provide atopy-related information for that child, leaving a final sample of 676.

Procedures

Participation included written informed consent for mothers and adult children (18+ years), oral assent for children ages 7–12 years, and written assent for children ages 13–17 years. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the participating institutions. All participants underwent a brief medical exam including blood pressure and anthropometry measurements, a fasting blood draw, and a personal interview. All interviews were conducted in a private room at the Hospital of Desio, Italy by trained nurse-interviewers who were blinded to the mother’s TCDD levels and zone of residence. During the interviews, adult children were asked about their reproductive and medical history, sociodemographic factors, and lifestyle characteristics. For children under the age of 18, mothers were interviewed about their children. Atopy-related questions were adapted from the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) questionnaire, which has been validated and standardized for international use [38]. Cases of eczema, asthma, and hay fever were defined in two ways: 1) maternal or self-report of a diagnosis and/or symptoms related to the conditions in the past 12 months, and 2) maternal or self-report of diagnosis only.

Diagnosis of eczema was determined by a positive answer to the question, “Have you (has your child) ever had eczema?” Additional symptom-based cases were determined by positive answers to the following three questions: “Have you (has your child) ever had an itchy skin rash which was coming and going for at least 6 months?” If yes: “Have you (has your child) had this itchy rash at any time in the past 12 months?” If yes: “Has this itchy rash at any time affected any of the following places—the folds of the elbows, behind the knees, in front of the ankles, under the buttocks or around the neck, ears or eyes?”

Diagnosis of asthma was defined by a positive response to the questions: “Has a doctor ever diagnosed you (your child) with asthma?” or “Have you (has your child) ever had asthma?” Additional symptom-based cases of asthma were determined by a positive response to any of the following during the previous 12 months: a) wheezing or whistling in the chest; b) wheezing in the chest during or after exercise or physical activity; and c) dry cough at night, apart from a cough associated with a cold or chest infection.

Diagnosis of hay fever was defined by a positive response to the question, “Have you (has your child) ever had hay fever?” Additional symptom-based cases were determined by a positive response to the question, “In the past 12 months, have you (has your child) had a problem with sneezing or a runny or blocked nose when you (your child) did not have a cold or the flu?”

Laboratory analysis

Details of the serum sample collection and TCDD concentration measurements are presented elsewhere [36, 39]. Maternal serum was collected soon after the explosion, and TCDD was measured in archived sera of adequate volume by high-resolution gas chromatography/high-resolution mass spectrometry methods at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [40]. Non-detectable TCDD values were assigned one-half of the detection limit. For this study, the median limit of detection was 18.8 ppt, lipid-adjusted [41]. We estimated maternal TCDD levels at pregnancy by extrapolation from the nearest TCDD measurement in 1976, 1996, or 2008 using a first-order kinetic model with a half-life that varies with initial dose, age, and covariates as described previously [37, 42]. TCDD values are reported on a lipid–weight basis as picograms per gram lipid or parts per trillion (ppt) [43].

Statistical analysis

Prenatal TCDD exposure was examined in two ways: 1) maternal initial (1976) serum TCDD level and 2) estimated TCDD at pregnancy. Initial TCDD levels were assessed to examine whether the primary dose permanently impacts the woman’s endocrine or reproductive system, resulting in heritable changes to her children. TCDD levels at pregnancy were assessed to determine whether direct fetal exposure during pregnancy impacts the child’s atopic outcomes. Because of the skewed distribution of TCDD values, the maternal 1976 TCDD and estimated TCDD at pregnancy variables were log10-transformed for all analyses. Lipid-adjusted values of TCDD concentration were analyzed as continuous variables. We fitted generalized additive models (GAMs) to explore the shape of the relationships between the exposures and outcomes. After transformation, the functions were sufficiently linear and no further transformation was necessary. Eczema, asthma, and hay fever were analyzed as binary variables (present vs. not present).

Potential covariates and confounders were identified a priori based on a directed acyclic graph (DAG) and existing literature on immune function, asthma, and allergic diseases [44,45,46,47,48]. Maternal variables considered included age at explosion and atopic history. Child-based variables included maternal age at pregnancy, maternal body mass index (BMI) closest to birth year, maternal smoking during pregnancy, pre-term birth, season of birth, breastfeeding duration, birth order, child sex, child age, and primary wage earner education status. Potential confounding variables from the DAG were considered for the regression models if they were significantly associated with at least one of the outcome variables in bivariate analyses (P < 0.2). Final models were adjusted for maternal age at explosion, atopic history, age at pregnancy, BMI closest to birth year, and smoking during pregnancy; child birth order, sex, and age; and primary wage earner education at follow-up.

Multivariable log-binomial regressions were used to examine the relationship between maternal TCDD levels and the risk of eczema, asthma, and hay fever. For models that were not able to converge using log-binomial regressions, Poisson regressions with a robust variance estimator were used [49]. These included the models that examined the association between TCDD estimated at pregnancy and hay fever defined by both symptomology and diagnosis. For all of the models, a clustered sandwich estimator of variance was used to account for non-independence of sibling clusters (n = 438 clusters) [50]. We also tested for effect modification by child sex in all models by including a cross-product term between the exposures and child sex. In sensitivity analyses, we repeated final models for asthma, excluding one person who self-reported a diagnosis of asthma, but did not report that it was doctor diagnosed. We also repeated final models for eczema, excluding one child who reported “don’t know” rather than “no” for self-report of a diagnosis of eczema. All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata, version 13 [51]. Statistical significance was set to be P-values < 0.05, unless otherwise specified. Interaction P-values < 0.2 were considered to be significant.

Results

Demographic and selected characteristics of our study sample are presented in Table 1. For the 438 mothers, the average age at explosion was 14.7 (standard deviation (SD) = ±8.0) years, and the average age at pregnancy was 29.8 (SD = ±5.1) years; 20.8% reported a history of asthma or allergy. Of the 676 children, 7.5% had mothers who were obese near the time of birth, 9.3% had mothers who smoked during pregnancy, 6.8% were born pre-term, 31.4% were breastfed for five or more months, 59.3% were first-born, and 50.3% were female. At interview, the average age of the children was 22.9 (SD = ±9.9) years, and 70.4% of the household primary wage earners had achieved an education of high school or greater. The distribution of births for each birth season was approximately equal (Table 1).

The median lipid-adjusted serum TCDD concentration near the time of the explosion for the 438 mothers was 64.7 ppt (interquartile range (IQR): 29.9–179.0), and the median estimated TCDD concentration at pregnancy was 11.2 ppt (IQR: 5.3–29.9). Consistent with our previous report, mothers who were youngest at the time of explosion had the highest median initial TCDD concentration (Table 1) [39].

Among the 676 children with known atopy status, there were 98 eczema, 152 asthma and 243 hay fever cases from maternal and self-report of diagnosis or symptoms. The average age at diagnosis was 10 years for eczema (n = 53), 7 years for asthma (n = 77), and 11 years for hay fever (n = 126). Compared to non-cases, children with eczema were more likely to have mothers who had a history of asthma or allergy. Females were less likely than males to have asthma. Children who were first born, had mothers with a history of asthma or allergy, and lived with a primary wage earner who was less educated were more likely to have hay fever (data not shown).

Table 2 presents the associations between maternal 1976 TCDD levels and eczema, asthma, and hay fever. Maternal 1976 TCDD was not associated with eczema (adjusted RR per 10-fold increase in TCDD = 0.93, 95% CI: 0.69, 1.27). When we limited the analysis to cases defined only by reported doctor diagnosis (n = 55), the results showed a significant inverse association between 1976 TCDD and eczema (adjusted RR = 0.63, 95% CI: 0.40, 0.99) (Table 2). Maternal 1976 TCDD was not associated with asthma or hay fever by either case definition. Unadjusted results are presented in Additional file 1: Table S1.

Table 3 presents the associations between TCDD estimated at pregnancy and eczema, asthma, and hay fever. We found no evidence of a significant association between TCDD estimated at pregnancy and eczema (adjusted RR per 10-fold increase in TCDD = 0.90, 95% CI: 0.60, 1.38), asthma (adjusted RR = 0.93, 95% CI: 0.65, 1.34), or hay fever (adjusted RR = 1.09, 95% CI: 0.90, 1.31). All associations remained non-significant when we limited the samples to include cases defined by a diagnosis only (Table 3).

There was limited evidence of effect modification by child sex on the relationship between maternal 1976 TCDD or TCDD estimated at pregnancy and atopic conditions. Specifically, among the samples that included cases defined by both a diagnosis and symptomatology, we found no evidence of effect modification by child sex on maternal 1976 TCDD and eczema (p-interaction = 0.54) or asthma (p-interaction = 0.72). However, there was evidence of effect modification by child sex for hay fever (p = 0.07) with non-significantly increased risk among female children (adjusted RR = 1.20, 95% CI: 0.95, 1.52) but not male children (adjusted RR = 0.91, 95% CI: 0.73, 1.13) (Table 2). However, there was no evidence of effect modification by sex on TCDD estimated at pregnancy and eczema (p-interaction = 0.75), asthma (p-interaction = 0.34), or hay fever (p-interaction = 0.67) (Table 3). Similarly, among the samples that included only diagnosis-based case definitions, we found no evidence of effect modification by child sex on maternal 1976 TCDD or TCDD estimated at pregnancy and atopic conditions (Tables 2 and 3).

In sensitivity analyses, we repeated the final models for asthma, excluding the one asthma case that was not doctor diagnosed, and also repeated the final models for eczema, excluding one child who reported “don’t know” for their condition status. The results were similar (data not shown).

Discussion

In this analysis of children of mothers who were exposed to TCDD in Seveso, Italy in 1976, we found no evidence of an association between maternal 1976 serum TCDD or TCDD estimated at pregnancy and asthma or hay fever although there was a non-significantly higher risk in females than males in some analyses. However, we observed a significant inverse association between eczema and initial 1976 TCDD, and a non-significant inverse relationship with eczema and TCDD estimated at pregnancy, with no strong evidence of differences by sex.

The decreased risk of eczema is consistent with three previous studies. A study in the Netherlands found that both prenatal and postnatal exposure to dioxin concentrations measured in breast milk had a non-significant inverse relationship with eczema [31]. Two studies in Norway also reported a non-significant inverse relationship between maternal dietary exposure to dioxins and dioxin-like polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) at the 22nd week of gestation and the risk of eczema and itchiness in the face and joints [22, 23].

However, in contrast to our null findings of TCDD and asthma symptomatology and allergy, one of the Norwegian studies found an increased risk of wheeze [23], and a Japanese cohort study of 18-month olds found an increased risk for maternal report of food allergies associated with polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins (PCDD), polychlorinated dibenzofurans (PCDF), and dioxin-like PCBs measured in maternal blood in the third trimester [30]. While these two studies did find an increased risk, the children in the Norwegian study were one-year-old, and most wheeze symptoms subside when children reach ages three to five [23], and the Japanese study measured food allergies, which may be related to food intolerance instead of the immune system or atopic conditions [30]. On the other hand, a Dutch study of four-year-olds found a decreased risk of asthma-related symptoms associated with prenatal exposure to dioxin-like PCBs [27], which persisted to school-age [26], but there was no association found for total dioxin toxic equivalents (TEQ). Another Dutch study of older children with prenatal and postnatal exposure to dioxins measured in the mother’s breast milk shortly after birth also reported a decreased risk in allergies [31]. The levels of dioxin are lower in these studies [27, 31] than in the Seveso cohort [40, 43], and some studies measured a mixture of PCBs, which also included non-dioxin-like compounds [26], while others measured a combination of PCDDs, PCDFs, and other dioxin-like compounds [26, 27, 30, 31].

The decreased risk of eczema can be explained by immunomodulatory effects of TCDD [52]. Although a decrease in eczema appears beneficial, the mechanisms underlying this occurrence may be related to other immunotoxic effects of TCDD, such as diminishing the mobilization of immune cells or suppressing adaptive immune responses, including some eczemas. The influence of TCDD on immunoregulation has been widely proposed to be related to its interaction with the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR). TCDD is a potent AhR ligand, and its activation of the receptor alters many downstream signals that shape immune response. For example, TCDD exposure may interfere with the balance of regulatory T (Treg) cells and Type 1 (TH1) and Type 2 (TH2) helper T cells [52]. These cells influence other immune cells’ response to antigens, such as initiating the production of immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies that cause allergic reactions. AhR-mediated responses with TCDD may expand Treg and TH1 helper cell populations, while suppressing TH2 cell immune responses [52, 53]. Another AhR-mediated mechanism by which TCDD may impact eczema risk is by affecting the skin barrier. In mice, in utero exposure to TCDD increased epidermal barrier formation via activation of the AhR [54] and increased expression of the filaggrin gene; a deficiency and mutation in filaggrin has been associated with eczema [55]. In vitro studies also show that TCDD exposure accelerates keratinocyte differentiation [56]. Therefore, there may be an interplay of dermatological and immunomodulatory responses from TCDD’s interaction with AhR, resulting in lower risk of eczema.

The immunomodulatory effects of prenatal and perinatal TCDD exposure have also been reported in animal studies. For example, hematopoietic progenitor cells from offspring of rodents exposed to TCDD had decreased B and T-lymphocyte differentiation capacity, compared to offspring of unexposed rats [17, 57]. In mice, male offspring of dams exposed to TCDD during both gestation and lactation exhibited a decrease in spleen weights and interleukin-4 production of splenic immune cells [33]. Another study of perinatally-exposed rats reported similar findings of decreased thymus/body weight ratio, delayed-type hypersensitivity response, and percentage of splenic CD3+/CD4 − CD8− cells, which are signs of attenuated cell-mediated immunity [18]. Furthermore, mice perinatally exposed to TCDD and sensitized with injections of ovalbumin exhibited lower serum levels of allergen-specific IgE, indicating that perinatal exposure to TCDD may lead to decreased allergic sensitization [58].

An explanation for why we did not observe significant associations in asthma or hay fever may be explained by the natural history of atopic disorders, known as the atopic march. Atopic march refers to the development of atopic eczema and hypersensitivity to food or other allergens in early childhood, and later progressing to asthma and allergic rhinitis, or hay fever, in later life [1]. The majority of children in our sample were diagnosed with the outcomes during childhood. However, age at diagnosis was by maternal or self-report, which may not be accurate. If age at diagnosis for eczema was understated and the children were diagnosed with eczema after asthma or hay fever, then there may be other mechanisms underlying the null associations between TCDD and the other atopic conditions. However, if in utero exposure to TCDD did minimize the development of eczema, this may have created a dent in the progression of the atopic march, and subsequent asthma and hay fever may not be observed.

The significant association observed for initial TCDD exposure and not TCDD estimated at pregnancy may indicate that initial body burden at the time of exposure is the relevant dose in impacting the children’s health outcomes. TCDD exposure at the time of the accident may have induced an epigenetic change in the women’s oocytes, allowing for a transgenerational inheritance of disease outcomes [59, 60]. However, we still cannot rule out that direct prenatal exposure at the time of pregnancy is also a relevant dose because our results for TCDD exposure at pregnancy do show a tendency of decreased risk of eczema, and our study’s pregnancy-TCDD levels were only estimated measurements.

Our results also show different significant associations across the three outcomes based on the case definition used. For example, we only observed a significant association for eczema in the diagnosis-based case definition. This may be due to misclassification in symptomatology, and we observed a significant result because the diagnosis-based case definition is more accurate and specific than the one that also includes related symptoms. The opposite was true for hay fever, where we observed a significant p-interaction value for the broader case definition. This may be because hay fever is more difficult to diagnose and people may not get it diagnosed because of how common it occurs. Thus, using the diagnosis-based case definition alone may have been less sensitive and missed some cases. There are some limitations to consider when interpreting these results. First, we were not able to confirm outcomes with medical records and relied on maternal or child report, so there may be outcome misclassification. However, we do not expect there to be differential misclassification or respondent bias because the interviewers and respondents were unaware of the TCDD levels and study hypotheses. Another limitation is potential residual confounding that could have impacted our results. For example, we were not able to control for the child’s delivery type because of limited available data, and a cesarean delivery has been shown to increase the risk of developing atopic diseases [44]. Lastly, although we have an accurate measure of initial TCDD levels, we estimated TCDD at pregnancy, which may lead to non-differential measurement error for prenatal exposure. This misclassification would bias our results towards the null because the degree of exposure misclassification is not related to outcome status; the same modeling approach was used to estimate TCDD at pregnancy across all outcomes and so would not explain the specific inverse finding with eczema.

This study has several strengths. First, it is a population-based prospective cohort established based on residence at the time of explosion, which allowed us to better assess causality and measure multiple outcomes related to atopy and immune functioning. To our knowledge, the SWHS cohort represents the largest female TCDD-exposed population with individual-level TCDD exposure data [36]. Also, because serum TCDD was obtained from blood samples taken near the time of the accident, we have a direct measure of the individual’s exposure level as opposed to other studies that have relied on indirect measures such as maternal dietary levels [22, 23]. Therefore, we were able to reduce exposure misclassification with biologic measurements. Another advantage compared to other studies is that exposure was predominantly to TCDD, whereas other studies examined other dioxin-like compounds including PCDD, PCDF, and dioxin-like PCBs. In our study, levels of other dioxin-like compounds were not elevated above background levels although 1976 background levels were high, compared to more recent studies [42].

Conclusions

In summary, we found that maternal serum TCDD levels near the time of explosion were associated with lower risk of eczema but there was no relationship with asthma or hay fever among children of the SWHS second generation cohort. The results are consistent with the dysregulated immune effects of TCDD observed in both animals and human studies, and support other evidence suggesting that prenatal TCDD exposure may increase the development of infectious diseases and decrease allergic conditions. With continued follow-up of SWHS children using antibody titer data and more accurate measurements of TCDD at pregnancy, we will begin to better elucidate mechanisms underlying these findings.

Abbreviations

- AhR:

-

Aryl hydrocarbon receptor

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- DAG:

-

Directed acyclic graph

- GAM:

-

Generalized additive models

- IgE:

-

Immunoglobulin E

- IgG:

-

Immunoglobulin G

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- ISAAC:

-

International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood

- PCB:

-

Polychlorinated biphenyls

- PCDD:

-

Polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins

- PCDF:

-

Polychlorinated dibenzofurans

- ppt:

-

Parts per trillion

- RR:

-

Relative risk

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SWHS:

-

Seveso Women’s Health Study

- TCDD:

-

Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin

- TEQ:

-

Total dioxin toxic equivalents

- TH1:

-

Type 1

- TH2:

-

Type 2

- Treg:

-

Regulatory T

References

Thomsen SF. Epidemiology and natural history of atopic diseases. Eur Clin Respir J. 2015;2:1–6.

Winans B, Humble MC, Lawrence BP. Environmental toxicants and the developing immune system: a missing link in the global battle against infectious disease? Reprod Toxicol. 2011 Apr;31(3):327–36.

Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Toxicological Profile for Chlorinated Dibenzo-p-Dioxins. Atlanta, GA: Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry; 1998.

Needham L, Gerthoux P, Patterson DG, et al. Half-life of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin in serum of Seveso adults: interim report. Organohalogen Compd. 1994;21:81–5.

Baan R, Grosse Y, Straif K, et al. A review of human carcinogens--part F: chemical agents and related occupations. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:1143–4.

Birnbaum L. Developmental effects of dioxins and related endocrine disrupting chemicals. Toxicol Lett. 1995;82–83:743–50.

White SS, Birnbaum LS. An overview of the effects of dioxins and dioxin-like compounds on vertebrates, as documented in human and ecological epidemiology. J Environ Science Health Environ Carcinog Ecotoxicol Rev. 2009;27:197–211.

Kaplan BL, Crawford RB, Kovalova N, et al. TCDD adsorbed on silica as a model for TCDD contaminated soils: evidence for suppression of humoral immunity in mice. Toxicology. 2011;282(3):82–7.

Ishikawa S. Children's immunology, what can we learn from animal studies (3): impaired mucosal immunity in the gut by 2,3,7,8-tetraclorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD): a possible role for allergic sensitization. J Toxicol Sci. 2009;34(Suppl 2):SP349–61.

Vorderstrasse BA, Bohn AA, Lawrence BP. Examining the relationship between impaired host resistance and altered immune function in mice treated with TCDD. Toxicology. 2003;188(1):15–28.

Kuwatsuka Y, Shimizu K, Akiyama Y, et al. Yusho patients show increased serum IL-17, IL-23, IL-1β, and TNFα levels more than 40 years after accidental polychlorinated biphenyl poisoning. J Immunotoxicol. 2014;11(3):246–9.

Nakamoto M, Arisawa K, Uemura H, et al. Association between blood levels of PCDDs/PCDFs/dioxin-like PCBs and history of allergic and other diseases in the Japanese population. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2013;86(8):849–59.

Kim HA, Kim EM, Park YC, et al. Immunotoxicological effects of agent Orange exposure to the Vietnam war Korean veterans. Ind Health. 2003;41(3):158–66.

Van Den Heuvel RL, Koppen G, Staessen JA, et al. Immunologic biomarkers in relation to exposure markers of PCBs and dioxins in Flemish adolescents (Belgium). Environ Health Perspect. 2002;110(6):595–600.

Ernst M, Flesch-Janys D, Morgenstern I, et al. Immune cell functions in industrial workers after exposure to 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin: dissociation of antigen-specific T-cell responses in cultures of diluted whole blood and of isolated peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Environ Health Perspect. 1998;106(Suppl 2):701–5.

Gogal RM Jr, Holladay SD. Perinatal TCDD exposure and the adult onset of autoimmune disease. J Immunotoxicol. 2008;5(4):413–8.

Laiosa MD, Tate ER, Ahrenhoerster LS, et al. Effects of developmental activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor by 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin on long-term self-renewal of murine hematopoietic stem cells. Environ Health Perspect. 2016;124(7):957–65.

Gehrs BC, Riddle MM, Williams WC, et al. Alterations in the developing immune system of the F344 rat after perinatal exposure to 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin: II. Effects on the pup and the adult. Toxicology. 1997;122(3):229–40.

Mustafa A, Holladay SD, Witonsky S. A single mid-gestation exposure to TCDD yields a postnatal autoimmune signature, differing by sex, in early geriatric C57BL/6 mice. Toxicology. 2011;290(2–3):156–68.

Hansen S, Strøm M, Olsen SF, et al. Maternal concentrations of persistent organochlorine pollutants and the risk of asthma in offspring: results from a prospective cohort with 20 years of follow-up. Environ Health Perspect. 2014;122(1):93–9.

Hansen S, Strøm M, Olsen SF, et al. Prenatal exposure to persistent organic pollutants and offspring allergic sensitization and lung function at 20 years of age. Clin Exp Allergy. 2016;46(2):329–36.

Stølevik SB, Nygaard UC, Namork E, et al. Prenatal exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls and dioxins from the maternal diet may be associated with immunosuppressive effects that persist into early childhood. Food Chem Toxicol. 2013;51:165–72.

Stølevik SB, Nygaard UC, Namork E, et al. Prenatal exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls and dioxins is associated with increased risk of wheeze and infections in infants. Food Chem Toxicol. 2011;49(8):1843–8.

Gascon M, Vrijheid M, Martínez D, et al. Pre-natal exposure to dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene and infant lower respiratory tract infections and wheeze. Eur Respir J. 2012;39(5):1188–96.

Jusko TA, De Roos AJ, Schwartz SM, et al. Maternal and early postnatal polychlorinated biphenyl exposure in relation to total serum immunoglobulin concentrations in 6-month-old infants. J Immunotoxicol. 2011;8(1):95–100.

Weisglas-Kuperus N, Vreugdenhil HJ, Mulder PG. Immunological effects of environmental exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls and dioxins in Dutch school children. Toxicol Lett. 2004;149(1–3):281–5.

Weisglas-Kuperus N, Patandin S, Berbers GA, et al. Immunologic effects of background exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls and dioxins in Dutch preschool children. Environ Health Perspect. 2000;108(12):1203–7.

Ashley-Martin J, Levy AR, Arbuckle TE, et al. Maternal exposure to metals and persistent pollutants and cord blood immune system biomarkers. Environ Health. 2015;14:52.

Kishi R, Kobayashi S, Ikeno T, et al. Ten years of progress in the Hokkaido birth cohort study on environment and children's health: cohort profile--updated 2013. Environ Health Prev Med. 2013;18(6):429–50.

Miyashita C, Sasaki S, Saijo Y, et al. Effects of prenatal exposure to dioxin-like compounds on allergies and infections during infancy. Environ Res. 2011;111(4):551–8.

ten Tusscher GW, Steerenberg PA, van Loveren H, et al. Persistent hematologic and immunologic disturbances in 8-year-old Dutch children associated with perinatal dioxin exposure. Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111(12):1519–23.

Reichrtová E, Ciznár P, Prachar V, et al. Cord serum immunoglobulin E related to the environmental contamination of human placentas with organochlorine compounds. Environ Health Perspect. 1999;107(11):895–9.

van Esterik JC, Verharen HW, Hodemaekers HM, et al. Compound- and sex-specific effects on programming of energy and immune homeostasis in adult C57BL/6JxFVB mice after perinatal TCDD and PCB 153. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2015;289(2):262–75.

di Domenico A, Silano V, Viviano G, et al. Accidental release of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) at Sèveso, Italy. II TCDD distribution in the soil surface layer Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 1980;4(3):298–320.

Baccarelli A, Pesatori AC, Masten SA, et al. Aryl-hydrocarbon receptor-dependent pathway and toxic effects of TCDD in humans: a population-based study in Seveso, Italy. Toxicol Lett. 2004;149(1–3):287–93.

Eskenazi B, Mocarelli P, Warner M, et al. Seveso Women’s health study: a study of the effects of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin on reproductive health. Chemosphere. 2000;40:1247–53.

Eskenazi B, Ames, J, Mocarelli P, Brambilla P, Signorini S, Warner M. 2016. In utero dioxin exposure and birth outcomes in the Seveso second generation. In: Abstracts of the 2016 conference of the International Society of Environmental Epidemiology (ISEE). Abstract O-186. Research Triangle Park, NC: Environmental health perspectives; https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.isee2016

Ellwood P, Asher MI, Beasley R, et al. The international study of asthma and allergies in childhood (ISAAC): phase three rationale and methods. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2005;9(1):10–6.

Eskenazi B, Mocarelli P, Warner M, et al. Relationship of serum TCDD concentrations and age at exposure of female residents of Seveso, Italy. Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112(1):22–7.

Patterson DG Jr, Hampton L, Lapeza CR Jr, et al. High-resolution gas chromatographic/high-resolution mass spectrometric analysis of human serum on a whole-weight and lipid basis for 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin. Anal Chem. 1987;59(15):2000–5.

Hornung RW, Reed LD. Estimation of average concentration in the presence of non-detectable values. Appl Occup Environ Hyg. 1990;5:48–51.

Warner M, Mocarelli P, Brambilla P, et al. Serum TCDD and TEQ concentrations among Seveso women, 20 years after the explosion. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2014;24(6):588–94.

Akins JR, Waldrep K, Bernert JT Jr. The estimation of total serum lipids by a completely enzymatic ‘summation’ method. Clin Chim Acta. 1989;184(3):219–26.

MacGillivray DM, Kollmann TR. The role of environmental factors in modulating immune responses in early life. Front Immunol. 2014;5:434.

Leifer CA, Dietert RR. Early life environment and developmental immunotoxicity in inflammatory dysfunction and disease. Toxicol Environ Chem. 2011;93(7):1463–85.

Sly PD, Holt PG. Role of innate immunity in the development of allergy and asthma. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;11(2):127–31.

Johnson CC, Ownby DR, Zoratti EM, et al. Environmental epidemiology of pediatric asthma and allergy. Epidemiol Rev. 2002;24(2):154–75.

Husband AJ, Gleeson M. Ontogeny of mucosal immunity—environmental and behavioral influences. Brain Behav Immun. 1996;10(3):188–204.

Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159(7):702–6.

Zou GY, Donner A. Extension of the modified Poisson regression model to prospective studies with correlated binary data. Stat Methods Med Res. 2013;22(6):661–70.

Stata Corp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13.0. Stata Press; College Station, TX: 2013.

Kerkvliet NI. AHR-mediated immunomodulation: the role of altered gene transcription. Biochem Pharmacol. 2009;77(4):746–60.

Palomares O, Yaman G, Azkur AK, et al. Role of Treg in immune regulation of allergic diseases. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40(5):1232–40.

Sutter CH, Bodreddigari S, Campion C, et al. 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin increases the expression of genes in the human epidermal differentiation complex and accelerates epidermal barrier formation. Toxicol Sci. 2011;124(1):128–37.

Loertscher JA, Lin TM, Peterson RE, et al. In utero exposure to 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin causes accelerated terminal differentiation in fetal mouse skin. Toxicol Sci. 2002;68(2):465–72.

Loertscher JA, Sattler CA, Allen-Hoffmann BL. 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin alters the differentiation pattern of human keratinocytes in organotypic culture. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2001;175:121–9.

Ahrenhoerster LS, Tate ER, Lakatos PA, et al. Developmental exposure to 2,3,7,8 tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin attenuates capacity of hematopoietic stem cells to undergo lymphocyte differentiation. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2014;277(2):172–82.

Tarkowski M, Kur B, Nocuń M, et al. Perinatal exposure of mice to TCDD decreases allergic sensitisation through inhibition of IL-4 production rather than T regulatory cell-mediated suppression. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2010;23(1):75–83.

Nilsson EE, Skinner MK. Environmentally induced epigenetic transgenerational inheritance of disease susceptibility. Transl Res. 2015;165(1):12–7.

Manikkam M, Tracey R, Guerrero-Bosagna C, Skinner MK. (Dioxin TCDD) induces epigenetic transgenerational inheritance of adult onset disease and sperm Epimutations. Shioda T, ed PLoS One 2012;7(9):e46249.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the SWHS field staff, the participants and their families, and colleagues at CDC for specimen analysis.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [F06 TW02075–01], the United States Environmental Protection Agency [R82471], the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences [R01 ES007171 and 2P30-ESO01896–17], and the Regione Lombardia and Fondazione Lombardia Ambiente [#2896].

Availability of data and materials

The data used for this study are not publicly available because consent was not obtained from participants to do so.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MY, analyzed and interpreted data, drafted and revised manuscript; MW, conception of study and study design, guided data analysis and interpretation, revised manuscript; PM, conception of study and study design; PB, conception of study and study design; BE, conception of study and study design, guided data analysis and interpretation, revised manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Research protocols were approved by the ethics and research committees of the University of California, Berkeley, and all participants provided informed consent prior to enrollment.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Table S1. Unadjusted regression models for associations of maternal 1976 TCDD and TCDD estimated at pregnancy with child atopic conditions, SWHS, Italy, 1976–2016. (DOCX 14 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Ye, M., Warner, M., Mocarelli, P. et al. Prenatal exposure to TCDD and atopic conditions in the Seveso second generation: a prospective cohort study. Environ Health 17, 22 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-018-0365-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-018-0365-2