Abstract

Background

Mobile clinics have been used to deliver primary health care to populations that otherwise experience difficulty in accessing services. Indigenous populations in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States experience greater health inequities than non-Indigenous populations. There is increasing support for Indigenous-governed and culturally accessible primary health care services which meet the needs of Indigenous populations. There is some support for primary health care mobile clinics implemented specifically for Indigenous populations to improve health service accessibility. The purpose of this review is to scope the literature for evidence of mobile primary health care clinics implemented specifically for Indigenous populations in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States.

Methods

This review was undertaken using the Joanna Brigg Institute (JBI) scoping review methodology. Review objectives, inclusion criteria and methods were specified in advance and documented in a published protocol. The search included five academic databases and an extensive search of the grey literature.

Results

The search resulted in 1350 unique citations, with 91 of these citations retrieved from the grey literature and targeted organisational websites. Title, abstract and full-text screening was conducted independently by two reviewers, with 123 citations undergoing full text review. Of these, 39 citations discussing 25 mobile clinics, met the inclusion criteria. An additional 14 citations were snowballed from a review of the reference lists of included citations. Of these 25 mobile clinics, the majority were implemented in Australia (n = 14), followed by United States (n = 6) and Canada (n = 5). No primary health mobile clinics specifically for Indigenous people in New Zealand were retrieved. There was a pattern of declining locations serviced by mobile clinics with an increasing population. Furthermore, only 13 mobile clinics had some form of evaluation.

Conclusions

This review identifies geographical gaps in the implementation of primary health care mobile clinics for Indigenous populations in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States. There is a paucity of evaluations supporting the use of mobile clinics for Indigenous populations and a need for organisations implementing mobile clinics specifically for Indigenous populations to share their experiences. Engaging with the perspectives of Indigenous people accessing mobile clinic services is imperative to future evaluations.

Registration

The protocol for this review has been peer-reviewed and published in JBI Evidence Synthesis (doi: 10.11124/JBISRIR-D-19-00057).

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Accessible primary health care is an inherent human right for all populations, as stipulated by the Declaration of Alma-Ata (1978) [1]. Primary health care encompasses early interventions delivered by general practitioners, nurses and allied health professionals such as health promotion, screening for disease and health education for disease prevention [1, 2]. Evidence supports the effectiveness of primary health care services in improving the management of chronic disease and addressing risk factors for developing chronic disease, across a range of contexts [3,4,5,6]. However, primary health care services are not always accessible for all populations. This is the case for Indigenous populations in Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States, who often experience racism, cultural, transport and financial barriers when accessing health services [7,8,9,10].

The multi-dimensional nature of health care access is well documented which includes the availability, accessibility, accommodation, affordability, acceptability and awareness of health care services [11, 12]. For Indigenous people, an important component of health care access is the provision of culturally safe and holistic health care by a trusted health professional who respects their values, traditions and customs [13,14,15]. Across the globe, Indigenous populations are culturally and linguistically diverse, with differing environmental contexts (e.g. climates, connections to land and waterways), cultural practices (e.g. lore, customs, spiritual beliefs) and cultural identities (e.g. kinship ties, ancestors) [16]. In modern states with a history of invading Indigenous lands through the process of colonization (e.g. Australia, Canada, New Zealand and United States), there are numerous Indigenous nations, tribes and clans, all with unique cultural identities, histories and languages [16]. However, there are similarities in the experience of colonialization for Indigenous people (e.g. racism, violence, experience of European communicable diseases and loss of land), particularly in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States, which has led to enduring inequity [7, 17, 18].

To redress health inequities for Indigenous populations, including the burden of chronic disease and high mortality rate compared to non-Indigenous populations [18], culturally safe models of health care are needed which improve the accessibility of primary health care services [19]. Evidence supports that a greater participation of Indigenous people in their health care leads to better health outcomes [20, 21]. Therefore, Indigenous-governed health care services are inherent to the provision of culturally accessible health care [22]. In Australia, over 140 Aboriginal Community-Controlled Health Services (ACCHOs) provide primary health care services to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people [23]. Internationally, evidence supports the important contribution of Indigenous-governed health organisations in providing culturally safe and accessible primary health care for Indigenous populations [24,25,26,27].

Mobile clinics implemented specifically for Indigenous populations and governed by Indigenous health organisations, may be one way to improve the accessibility of culturally safe primary health care for Indigenous populations. It is known that mobile clinics are able to deliver health care to populations experiencing health inequity, particularly in countries where health care can be otherwise inaccessible due to transport, financial or cultural barriers [28,29,30]. In the United States, there has been an upward surge in the implementation of mobile clinics, particularly of mobile clinics delivering primary health care services [31, 32]. The support for mobile clinics in providing flexible and safe health care to vulnerable people has gained traction with the recent COVID-19 pandemic [33]. In other countries, mobile clinics have also been implemented with the purpose of screening for communicable and non-communicable diseases [34,35,36] and providing disaster relief [37, 38]. Some research supports the potential for mobile clinics to be a cost-effective model of health care and improve the management of chronic disease [29, 39].

There is also some evidence of mobile clinics being implemented specifically for Indigenous populations, either by an Indigenous health organization [40] or for a specific disease (e.g. diabetes) [41] or treatment (e.g. dialysis) [42]. What is not known, is the available evidence regarding the use of primary health care mobile clinics implemented specifically for Indigenous populations in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States who share a similar history of colonization, discrimination and barriers to accessing primary health care services [7]. This was apparent when undertaking a preliminary search of the literature for evidence around the effectiveness of mobile clinics for Indigenous populations, as part of seeking funding for a mobile clinic to be implemented in an Australian ACCHO. Indeed, it was an absence of evidence that made it difficult to obtain funding for the mobile clinic, justifying the need for a systematic scoping review. It is known that there is a vast body of literature regarding mobile clinics in the United States, yet there is very little focus on Native American, Native Hawaiian, and Alaskan Native populations [32]. A systematic scoping review was conceptualised to synthesise the available evidence regarding the use of primary health care mobile clinics implemented specifically for Indigenous populations in order to identify gaps in the literature and inform future research evaluating mobile clinics for Indigenous populations. Specifically, the review question developed was:

What is the evidence surrounding the use of mobile primary healthcare clinics implemented for Indigenous populations in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States?

Specific objectives were to: (1) scope the models of primary health care clinics for Indigenous populations (in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States) as described in the literature, (2) determine geographically where mobile primary health care clinics for Indigenous populations (in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States) have been implemented and, (3) examine the findings of any evaluations of mobile primary health care clinics for Indigenous populations (in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States) that have been published in the literature.

Methods

This systematic scoping review examines the evidence surrounding the use of mobile primary healthcare clinics implemented for Indigenous populations in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States [43]. This review was conducted in accordance with the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Reviewer’s Manual 2017: Methodology for JBI Scoping Reviews [44]. Search terms were developed using a PCC (Population, Concept, Context) mnemonic. The premise and methods of this review, have been published elsewhere [43]. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis extension for scoping reviews checklist (PRISMA-ScR) [45] was adhered to in the reporting of this review (Additional file 1_PRISMA-ScR checklist).

Search strategy

The JBI three step search process was utilized to develop the search strategy [44]. This involved a preliminary search undertaken in MEDLINE and CINAHL using keywords from the review question. A tailored search was then developed for each information source. For database search strategies, a combination of Boolean operators, truncations and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) were used (Additional file 2_ Academic database search strategies). Librarian assistance was provided for the development of the Ovid MEDLINE search strategy. Support was also provided in translating the search strategies into other databases. The reference lists of included studies were then searched for additional studies.

Databases searched included: Ovid MEDLINE, CINAHL (EBSCOhost), Embase (Elsevier), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, SocINDEX (EBSCOhost), and INFORMIT.

Multiple platforms were used to search for unpublished studies and grey literature which included: Australian, Canadian, New Zealand, and the United States Indigenous-specific research websites, Indigenous organisational websites, health services and health research websites and open access websites, repositories and catalogues (Additional file 3_Grey Literature sources).

Inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria

Literature based on the following criteria was considered (Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria).

No restrictions were placed on the quality or study design used. All types of literature, including media releases, webpages and news articles, were considered. Literature published since 1 January 2006 was considered in order to capture mobile clinics implemented since the ‘United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples’ (2007), where a greater international focus on the need to work in partnership with Indigenous populations to improve health outcomes, was established [46].

For consistency, the term ‘Indigenous’ has been used throughout this review to refer to all clans, tribes and communities of Indigenous populations within a global context. We acknowledge the diversity and uniqueness of all Indigenous tribes, clans and nations. No disrespect is intended by the use of this term.

Study selection and data extraction

Searches for published and unpublished literature were conducted by two researchers (HB and GE). Titles and abstracts retrieved were screened independently by two reviewers (HB and GE). Full text review and data extraction were then undertaken independently by the same two reviewers. For articles not meeting the inclusion criteria, reasons for exclusion were provided. The reference lists of included citations were then screened for additional citations in order to scope for all possible citations meeting the inclusion criteria.

The published data extraction table was used and modified to extract the longitude and latitude coordinates for locations serviced by the included mobile clinics from publicly available information [43]. The coordinates were then imported into ArcGIS ArcMap 10.6.1 (ESRI, CA, USA), a Geographical Information System (GIS), and mapped as point locations. Using a spatial join, the coordinates were linked with an underlying geographical characteristic described either as the Remoteness Structure (Australia) [47], Population Centre and Rural Area Classification 2016 (Canada) [48], or Urban status (United States) [49] to determine the classification of locations serviced by included mobile clinics. It is important to note that each country included in this review has a different rural area classification system. In Australia, Remoteness Structure comprises five categories: Major Cities of Australia, Inner Regional Australia, Outer Regional Australia, Remote Australia, and Very Remote Australia [47]. These classifications offer complete coverage of the Australian continent. Population centers in Canada are described as Small (1000-29,999), Medium (30,000-99,999) or Large (100,000 and over) with all other areas not classified, indicating very low population densities [48]. The urban footprint in the United States (high population density and urban land use) are described as Urban Clusters (2500-49,999) and Urbanised areas (> 50,000) [49]. Like Canada, all other areas are not classified. The spatial data used was based upon each modern state’s most recent census – 2016 for Australia and Canada (next census due 2021), and 2010 for the United States (next census due 2020).

Review findings were developed using a descriptive approach that addressed the review objectives, as per the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Reviewer’s Manual 2017: Methodology for JBI Scoping Reviews [44]. This involved examining the evidence that met the inclusion criteria, providing a summary of citations and synthesising extracted data where possible (e.g. geographical characteristics of location(s) where mobile clinics were implemented).

Results

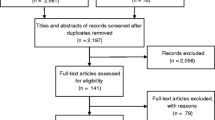

Database searches yielded 1672 citations. An additional 91 citations were retrieved from an extensive search of the grey literature and targeted organisational websites. A total of 1350 unique title and abstracts were screened, after duplicates were removed. The full texts of 123 citations were screened in accordance with the review criteria, identifying 39 relevant citations (Fig. 1– PRISMA Flow Diagram). An additional 14 citations were snow-balled from 39 included citations, resulting in a total of 53 included citations discussing 25 mobile clinics.

Reasons for excluding citations were provided (Additional file 4_Excluded studies) and included: not an Indigenous-specific mobile clinic (n = 39), no mobile clinic (n = 25), not a primary health care mobile clinic (n = 12), sub-studies already included in search (n = 3), sub-studies did not meet the inclusion criteria (n = 3) and audio-recording not available (n = 2).

Information sources of citations meeting the review criteria (n = 53) included peer-reviewed journal articles (n = 18), conference presentations, papers or posters (n = 3), thesis (n = 1), independent report (n = 1), organisational annual reports or web pages (n = 25), and media releases or online news articles (n = 5).

Finding 1: geographical distribution of mobile clinics for Indigenous populations

Of the 25 mobile clinics included (many servicing multiple locations), most were implemented in Australia (n = 14), followed by the United States (n = 6) and Canada (n = 5). No primary health care clinics implemented specifically for Māori populations in New Zealand, were retrieved from the search (Table 2).

In Australia, the majority of locations serviced by mobile clinics were located in Very Remote Australia (n = 44; Table 3; Fig. 2). This was compared to Inner and Outer Regional Australia, which both had a similar amount of locations represented (n = 15 and n = 17 respectively). The remoteness classification with the least amount of locations was Major Cities of Australia (n = 2).

In Canada, most locations serviced by a mobile clinic were outside the formal classification of population centres (n = 142; Table 3; Fig. 3). There was a declining presence of mobile clinics with the increasing size of population centres. This was similar to the United States where two thirds of mobile clinic activity was in areas classified as being outside Urbanised Areas or Urbanised Clusters (n = 24, Table 3; Fig. 3). Locations with a mobile clinic presence were more numerous in Urbanised Clusters (n = 11) compared to Urbanised Areas (n = 1).

Finding 2: primary health mobile clinic models for Indigenous populations

Of the mobile clinics included in the search (n = 25), the types of primary health care services and targeted populations varied (Table 3). These included delivering a broad range of general primary health care services (n = 13), providing disease specific services (e.g. diabetes management, screening and education n = 6, renal disease and other chronic disease screening n = 1, breast cancer screening n = 1, ear disease screening n = 3) and opportunistic health services and health promotion (n = 1) to Indigenous populations.

Most of the mobile clinics were implemented for Indigenous populations across the lifespan (n = 15), with fewer implemented for a specific age, gender group or population with chronic disease (infants, children or young people aged less than 18 years n = 4, people with diabetes n = 4, women n = 1, adults n = 1). There was evidence of Indigenous organisations governing and/or implementing 14 of the 25 mobile clinics (56%), with the remainder implemented in partnership with a non-Indigenous organisation or institution (n = 10). No information was provided about the involvement of Indigenous people in the implementation of one mobile clinic [67].

Information about the funding source(s) was retrieved for 19 of the 25 (76%) mobile clinics. Various sources were used to fund the mobile clinics which included governments, health organisations, commercial entities, universities and philanthropic organisations or foundations.

Finding 3: evidence of evaluated mobile clinics for Indigenous populations

Of the 25 included mobile clinics, 13 (52%) had evidence of some form of evaluation (Table 4). Of these 13 mobile clinics, most of the evaluation findings were disseminated in the non peer-reviewed literature or grey literature (n = 7 mobile clinics), with fewer evaluation findings disseminated in the peer-reviewed literature (n = 6 mobile clinics).

Of the evaluated mobile clinics, various approaches to undertaking an evaluation were used. Some evaluations produced multiple citations for a single mobile clinic (Table 4). Most of the evaluations used quantitative methods of evaluation (n = 11) including descriptive statistics (e.g. of clinical indicators, patient demographics, service data), surveys and longitudinal data. One of these included a cost-effectiveness analysis [52]. Two evaluations used a mixed methods approach consisting of both quantitative and qualitative methods of evaluation. Of the two mobile clinics evaluated using mixed methods (e.g. including qualitative methods of data collection such as interviews and focus group sessions), one evaluation did not provide qualitative data [63], whereas the other provided rich qualitative findings with evidence of engaging with the perspectives and voices of Indigenous people [65, 66]. Evaluations were heterogeneous in terms of evaluation methods and outcomes, making it difficult to compare findings. However, the participant sample included in evaluations was those receiving the services of the respective mobile clinic with a client or patient record (Table 4).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic scoping review examining primary health care mobile clinics implemented for Indigenous populations in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States. This review locates evidence of mobile clinics that have been implemented specifically for Indigenous populations (with the exception of New Zealand), and highlights the potential for mobile clinics to improve the accessibility of primary health care services. These findings are a valuable contribution to the growing body of international literature around the use of mobile clinics [28, 29, 32, 33, 36, 38]. Before discussing the implications of these findings, it is important to reiterate that Indigenous populations are diverse, have different languages, cultural identities, customs, lore and spiritual beliefs [16]. However, Indigenous populations in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States share the experience of colonization and require culturally safe health care embedded in the principles of self-determination [7, 16, 17, 46].

Likewise, there are key differences between the health care systems of Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States, which may account for variations in the implementation of mobile clinics specifically for Indigenous populations. Australia, Canada, and New Zealand have universal access to health care for all populations [100,101,102] which differs from the partially-funded health care system in the United States [103]. There are also complexities around the policies of each modern state regarding the funding of Indigenous-governed health services and programs [104]. In the United States, funding is allocated through the Indian Health Service (IHS), with a key criticism being the failure to provide sufficient resources to meet the health care needs (particularly primary health care needs) of a growing Native American, Native Alaskan, and Native Hawaiian population [17, 105]. In Australia and Canada, Indigenous health organisations (e.g. ACCHOs in Australia and on-reserve First Nations health services in Canada) receive some funding from governments to provide primary health care services to Indigenous populations, yet inequities exist in the distribution of funding (e.g. lack of funding for Métis People) and power imbalances between government and Indigenous health-organisations [17, 27, 104]. The funding structure in New Zealand differs again, with a more integrated approach of health service delivery through mainstream health services or private agencies and greater participation of Māori People in the process of informing the policy of District Health Boards (DHB) [17, 106]. The need to reform health care systems for the provision of equitable and culturally safe health care for Indigenous populations, has been widely discussed in the peer-reviewed literature [27, 104, 105].

There are also variations as to how population density is described in Australia, Canada, and the United States, which also has implications for interpreting the findings of this review (see Table 3). Australia’s Remoteness Structure [47] has a complete coverage of the continent, whereas Canada and the United States classify their urban areas by population size [48, 49]. Although there are other geographical methods for classifying population density (e.g. in Australia, Modified Monash Model [107]), this review has included classification methods used by decision-makers in each country at the time of analysis. For example, the Australian Government’s Rural Health Multidisciplinary Training (RHMT) Program [108] utilizes the Remoteness Structure [47] to guide investment to improve the recruitment and retention of health professionals in rural and remote Australia. Likewise, the Population Centre and Rural Area Classification 2016 (Canada) [48] and Urban status (United States) [49] are both based on the most recent census for each respective country and are used in government decision-making. Acknowledging these variations, this review identifies a pattern of increasing presence of mobile clinics in areas with lower population densities (see Table 3). Geographical gaps in service provision are evident (Figs. 2 and 3), indicating that the implementation of mobile clinics for Indigenous populations is not widespread.

There are also variations in the models of primary health care mobile clinics implemented for Indigenous populations. Most of the mobile clinics retrieved by this review targeted Indigenous populations across the lifespan, indicating a holistic family-centered model of primary health care, which is a preferred characteristic of Indigenous primary health care services [109]. Some mobile clinics targeted specific chronic diseases prevalent in Indigenous populations (e.g. diabetes) [110] and prevention of chronic disease for specific populations (e.g. otitis media in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children) [111]. Although there was some evidence of Indigenous organisational governance or involvement in the implementation of most mobile clinics, it was difficult to ascertain the degree of Indigenous community ownership. This is a key issue which has been discussed in another review examining chronic disease programs implemented for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations [112], and in the international literature examining health services and programs for Indigenous populations [27, 113, 114]. Indigenous community ownership of mobile clinics is imperative to ensuring culture, self-determination, and community participation are embedded in the delivery of primary health care services [109].

A paucity of published and publicly available evaluations of primary health care mobile clinics implemented specifically for Indigenous populations is also highlighted. This is despite a growing body of literature evaluating mobile clinics implemented for general populations and those at-risk for developing chronic disease, particularly in the United States [28, 31,32,33, 36, 39]. Although there is heterogeneity in the approaches used to evaluate mobile clinics implemented for Indigenous populations, there is some evidence that supports the potential for mobile clinics to increase attendance rates to services [54, 62, 69, 72] and improve clinical indicators (e.g. BMI, HbA1C) of targeted chronic diseases (e.g. diabetes) in Indigenous people accessing mobile clinic services [41, 79]. However, evaluation methods have relied heavily on the analysis of patient records and service data (see Table 4). The perspectives and insights of Indigenous people accessing mobile clinic services is largely absent. Findings support the need for high quality evaluations of Indigenous health programs which integrate qualitative evidence regarding the views and perspectives of Indigenous people [115]. An absence of qualitative data around the effectiveness of mobile clinics makes it difficult to know whether mobile clinics have potential to improve the cultural accessibility of primary health care services for Indigenous populations. This is a gap in existing knowledge which requires further research.

It is also difficult to examine how sustainable primary health care mobile clinics are when implemented for Indigenous populations. It is noted that the five diabetes mobile clinics retrieved from Canada were funded under the Aboriginal Diabetes Initiative (ADI), yet it is difficult to identify from the available literature as to whether all of these mobile clinics have been sustained over time under the original funding arrangement [79]. This highlights a key issue mediating the sustainability of mobile clinics in general, being the reliance on multiple funding sources (e.g. government and philanthropic) and/or short funding cycles [33]. There is also limited cost-effectiveness data around the use of mobile clinics for Indigenous populations [52]. Future research should include economic evaluations, coupled with an evaluation of the effectiveness and cultural acceptability of mobile clinics for Indigenous populations. This is imperative to informing the allocation of resources by decision-makers (e.g. governments and Indigenous-health organisations) to mobile clinics.

Limitations

Every effort has been made to search academic databases and grey literature sources for primary health care mobile clinics that have been implemented for Indigenous populations in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States. In Australia, it is known that a significant proportion of health research involving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations is published in the grey literature [116]. A thorough search of grey literature information sources across key websites has been undertaken through the independent searching of two researchers and follow up of organisations, authors and researchers for additional information. Therefore, a limitation of this review is the manual processes required to undertake this search and the acknowledgement that there is the potential for some mobile clinics to be missed due to this.

Conclusions

This review identifies geographical gaps and a paucity of evidence around the implementation of primary health care mobile clinics for Indigenous populations in Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States. The findings support the need to undertake rigorous mixed methods evaluations of primary health care mobile clinics implemented specifically for Indigenous populations. Through the involvement of Indigenous people in the evaluation process, greater insights will be obtained as to the potential for mobile clinics to improve access to culturally safe and holistic primary health care services. It is important for organisations implementing primary health mobile clinics for Indigenous populations, to share their experiences by making evaluations publicly available, ideally through the peer-reviewed literature. This is essential in developing evidence around innovative models of health care that have the potential to improve health outcomes for Indigenous people globally. Dissemination of evaluation evidence concerning mobile clinics will also be invaluable to decision-makers, including Indigenous health organisations, who are considering allocating resources to a primary health care mobile clinic.

Availability of data and materials

Geographical locations of mobile clinics are publicly available.

Abbreviations

- ACCHO:

-

Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation

- JBI:

-

Joanna Briggs Institute

- PCC:

-

Population, Concept, Context

- PRISMA - ScR:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Scoping Reviews

References

UNICEF, World Health Organization. International conference on primary health care. Declaration of Alma-Ata: international conference on primary health care [internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1978. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/almaata_declaration_en.pdf. Accessed Feb 4 2020.

Primary Health Care Research and Information Service. Primary health care matters. Adelaide: Primary Health Care Research & Information Service; 2014. Available from: https://dspace.flinders.edu.au/xmlui/bitstream/handle/2328/36334/factsheet_primary%20health%20care.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed Feb 4 2020.

Mitchell LJ, Ball LE, Ross LJ, Barnes KA, Williams LT. Effectiveness of dietetic consultations in primary health care: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2017;117(12):1941–62.

Black RE, Taylor CE, Arole S, Bang A, Bhutta ZA, Chowdhury AMR, et al. Comprehensive review of the evidence regarding the effectiveness of community-based primary health care in improving maternal, neonatal and child health: 8. Summary and recommendations of the expert panel. J Glob Health. 2017;7(1):433–44.

Álvarez-Bueno C, Rodríguez-Martín B, García-Ortiz L, Gómez-Marcos MÁ, Martínez-Vizcaíno V. Effectiveness of brief interventions in primary health care settings to decrease alcohol consumption by adult non-dependent drinkers: a systematic review of systematic reviews. Prev Med. 2015;76(Suppl 1):33–8.

Reynolds R, Dennis S, Hasan I, Slewa J, Chen W, Tian D, et al. A systematic review of chronic disease management interventions in primary care. BMC Fam Pract. 2018;19(1):1–13.

Paradies Y. Colonisation, racism and Indigenous health. J Popul Res. 2016;33(1):83–96.

Davy C, Harfield S, McArthur A, Munn Z, Brown A. Access to primary health care services for Indigenous peoples: a framework synthesis. Int J Equity Health. 2016;15(1):1–9.

Marrone S. Understanding barriers to health care: a review of disparities in health care services among Indigenous populations. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2007;66(3):188–98.

Filippi MK, Perdue DG, Hester C, Cully A, Cully L, Greiner A, et al. Colorectal Cancer screening practices among three American Indian communities in Minnesota. J Cult Divers. 2016;23(1):21–7.

Penchansky R, Thomas JW. The concept of access: definition and relationship to consumer satisfaction. Med Care. 1981;19(2):127–40.

Saurman E. Improving access: modifying Penchansky and Thomas’s theory of access. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2015;21(1):36–9.

Jennings W, Bond C, Hill PS. The power of talk and power in talk: a systematic review of Indigenous narratives of culturally safe healthcare communication. Aust J Prim Health. 2018;24(2):109–15.

Greenwood M, Lindsay N, King J, Loewen D. Ethical spaces and places: Indigenous cultural safety in British Columbia health care. AlterNative. 2017;13(3):179–89.

Ellison-Loschmann L, Pearce N. Improving access to health care among New Zealand’s Maori population. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(4):612–7.

United Nations. State of the World's Indigenous peoples [internet]. New York: United Nations; 2009. Available from: https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/SOWIP/en/SOWIP_web.pdf. Accessed Feb 4 2020.

Pulver L, Ring I, Waldon W, Whetung V, Kinnon D, Graham C, et al. Indigenous health – Australia, Canada, Aotearoa New Zealand and the United States - laying claim to a future that embraces health for us all. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. Available from: https://www.who.int/healthsystems/topics/financing/healthreport/IHNo33.pdf. Accessed 5 Feb 2020.

Anderson I, Robson B, Connolly M, Al-Yaman F, Bjertness E, King A, et al. Indigenous and tribal peoples' health (the lancet–Lowitja Institute global collaboration): a population study. Lancet. 2016;388(10040):131–57.

Gibson O, Lisy K, Davy C, Aromataris E, Kite E, Lockwood C, et al. Enablers and barriers to the implementation of primary health care interventions for Indigenous people with chronic diseases: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1):1–11.

Bath J, Wakerman J. Impact of community participation in primary health care: what is the evidence? Aust J Prim Health. 2015;21(1):2–8.

Reeve C, Humphreys J, Wakerman J, Carter M, Carroll V, Reeve D. Strengthening primary health care: achieving health gains in a remote region of Australia. Med J Aust. 2015;202(9):483–7.

Panaretto KS, Dellit A, Hollins A, Wason G, Sidhom C, Chilcott K, et al. Understanding patient access patterns for primary health-care services for Aboriginal and islander people in Queensland: a geospatial mapping approach. Aust J Prim Health. 2017;23(1):37–45.

National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (NACCHO). Annual Report 2018–2019. Canberra: National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (NACCHO); 2019. Available from: https://www.naccho.org.au/wp-content/uploads/NACHHO0043-Annual-Report-18-19-web-version.pdf. Accessed 5 Feb 2020.

Campbell MA, Hunt J, Scrimgeour DJ, Davey M, Jones V. Contribution of Aboriginal community-controlled health Services to improving Aboriginal health: an evidence review. Aust Health Rev. 2018;42(2):218–26.

Gomersall JS, Gibson O, Dwyer J, O'Donnell K, Stephenson M, Carter D, et al. What Indigenous Australian clients value about primary health care: a systematic review of qualitative evidence. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2017;41(4):417–23.

Beaton A, Manuel C, Tapsell J, Foote J, Oetzel JG, Hudson M. He Pikinga Waiora: supporting Māori health organisations to respond to pre-diabetes. Int J Equity Health. 2019;18(1):1–11.

Lavoie JG, Dwyer J. Implementing Indigenous community control in health care: lessons from Canada. Aust Health Rev. 2016;40(4):453–8.

Yu SWY, Hill C, Ricks ML, Bennet J, Oriol NE. The scope and impact of mobile health clinics in the United States: a literature review. Int J Equity Health. 2017;16(1):1–11.

Abdel-Aleem H, El-Gibaly OMH, El-Gazzar A, Al-Attar GST. Mobile clinics for women's and children's health. Cochrane Datab Syst Rev. 2016, Issue 8. Art. No.: CD009677. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009677.pub2.

Barker C, Bartholomew K, Bolton P, Walsh M, Wignall J, Crengle S, et al. Pathways to ambulatory sensitive hospitalisations for Māori in the Auckland and Waitemata regions. N Z Med J. 2016;129(1444):15–34.

Mobile Health Map. Find Clinics Mobile Health Map. Boston: Harvard Medical School; 2020. [cited 2020 February 10]. Available from: https://www.mobilehealthmap.org/map.

Malone NC, Williams MM, Smith Fawzi MC, Bennet J, Hill C, Katz JN, et al. Mobile health clinics in the United States. Int J Equity Health. 2020;19(1):1–9.

Attipoe-Dorcoo S, Delgado R, Gupta A, Bennet J, Oriol NE, Jain SH. Mobile health clinic model in the COVID-19 pandemic: lessons learned and opportunities for policy changes and innovation. Int J Equity Health. 2020;19(1):1–5.

Gutierrez-Padilla JA, Mendoza-Garcia M, Plascencia-Perez S, Renoirte-Lopez K, Garcia-Garcia G, Lloyd A, et al. Screening for CKD and cardiovascular disease risk factors using Mobile clinics in Jalisco, Mexico. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;55(3):474–84.

Dhore PB, Tiwari S, Mandal MK, Purandare VB, Sayyad MG, Pratyush DD, et al. Design, implementation and results of a mobile clinic-based diabetes screening program from India. J Diabetes. 2016;8(4):590–3.

Bertoncello C, Cocchio S, Fonzo M, Bennici SE, Russo F, Putoto G. The potential of mobile health clinics in chronic disease prevention and health promotion in universal healthcare systems. An on-field experiment. Int J Equity Health. 2020;19(1):1–9.

Rassekh BM, Shu W, Santosham M, Burnham G, Doocy S. An evaluation of public, private, and mobile health clinic usage for children under age 5 in Aceh after the tsunami: implications for future disasters. Health Psychol Behav Med. 2014;2(1):359–78.

McGowan CR, Baxter L, Deola C, Gayford M, Marston C, Cummings R, et al. Mobile clinics in humanitarian emergencies: a systematic review. Conflict Health. 2020;14(1):1–10.

Hill CF, Powers BW, Jain SH, Bennet J, Vavasis A, Oriol NE. Mobile health clinics in the era of reform. Am J Manag Care. 2014;20(3):261–4.

Budja Budja Aboriginal Cooperative. New Mobile clinical health Van [internet]. Halls Gap: Budja Budja Aboriginal Cooperative; 2020. Available from: https://budjabudjacoop.org.au/new-mobile-clinical-health-van-april-2019/. Accessed 31 Jan 2020.

Oster RT, Shade S, Strong D, Toth EL. Improvements in indicators of diabetes-related health status among first nations individuals enrolled in a community-driven diabetes complications mobile screening program in Alberta, Canada. Can J Public Health. 2010;101(5):410–4.

Conway J, Lawn S, Crail S, McDonald S. Indigenous patient experiences of returning to country: a qualitative evaluation on the country health SA Dialysis bus. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):1–13.

Beks H, Ewing G, Muir R, Charles J, Paradies Y, Clark R, et al. Mobile primary health care clinics for Indigenous populations in Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States: a scoping review protocol. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2020;18(5):1077–90.

Peters MDJ, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Baldini Soares C, Khalil H, Parker D. Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews. In: Areomataris E, Munn Z, editors. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual. Adelaide: Joanna Briggs Institute; 2017. Available from: https://reviewersmanual.joannabriggs.org/. Access 22 Jan 2020.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

United Nations General Assembly. United Nations declaration on the rights of Indigenous peoples [internet]. New York: United Nations General Assembly; 2008. [cited 2020 Feb 5]. Available from: https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/wp-content/uploads/sites/19/2018/11/UNDRIP_E_web.pdf. Accessed 5 Feb 2020.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). Remoteness structure. Canberra: ABS; 2018. http://www.abs.gov.au/websitedbs/D3310114.nsf/home/remoteness+ structure. Accessed 8 Jan 2020.

Canada Statistics. Population Centre and Rural Area Classification 2016. Ontario: Statistics Canada; 2017. Available from: http://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p3VD.pl? Function=getVD&TVD=339235. Accessed 8 Jan 2020.

United States Census Bureau Department of Commerce. TIGER/Line Shapefile, 2016, 2010 nation, U.S., 2010 census urban area national [internet]. United States Census Bureau: 2019. Available from: https://catalog.data.gov/dataset/tiger-line-shapefile-2016-2010-nation-u-s-2010-census-urban-area-national#sec-dates. Accessed 8 Apr 2020.

ABC News. Mobile health clinic to tour Indigenous communities. Ultimo: ABC News; 2008. Available from: https://help.abc.net.au/hc/en-us/articles/360001150496-What-are-the-contact-details-for-the-ABC-. Accessed 10 Feb 2020.

Elliott G, Smith AC, Bensink ME, Brown C, Stewart C, Perry C, et al. The feasibility of a community-based mobile telehealth screening service for Aboriginal and Torres Strait islander children in Australia. Telemed J E-health. 2010;16(9):950–6.

Nguyen KH, Smith AC, Armfield NR, Bensink M, Scuffham PA. Cost-effectiveness analysis of a Mobile ear screening and surveillance service versus an outreach screening, surveillance and surgical Service for Indigenous Children in Australia. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):1–16.

Smith AC, Armfield NR, Wu W-I, Brown CA, Mickan B, Perry C. Changes in paediatric hospital ENT service utilisation following the implementation of a mobile, Indigenous health screening service. J Telemed Telecare. 2013;19(7):397–400.

Smith AC, Bradford N, Caffery LJ, Armfield NR, Brown C, Perry C. Monitoring ear health through a telemedicine-supported health screening service in Queensland. J Telemed Telecare. 2015;21(8):427–30.

Smith AC, Armfield NR, Wu W-I, Brown CA, Perry C. A mobile telemedicine-enabled ear screening service for Indigenous children in Queensland: activity and outcomes in the first three years. J Telemed Telecare. 2012;18(8):485–9.

Alcohol and Other Drugs Knowledge Centre. Bega Garnbirringu Health Service Mobile Clinic. Mt Lawley: Alcohol and Other Drugs Knowledge Centre; 2020. Available from: https://aodknowledgecentre.ecu.edu.au/key-resources/programs-and-projects/1632/?title=Bega%20Garnbirringu%20Health%20Service%20Mobile%20Clinic. Accessed 10 Feb 2020.

Bega Garnbirringu Health Sevice. Mobile Clinic. Kalgoorlie: Bega Garnbirringu Health Service; 2020. Available from: https://bega.org.au/bega-clinical-services/mobile-clinic/. Accessed 10 Feb 2020.

Australian Mobile Health Clinics Association. Australian and State Government Policy Support for Mobile Health Care. Gordon: Australian Mobile Health Clinics Association; 2015. Available from: http://www.mobilehealthclinics.com.au/support-for-mobile-healthcare/. Accessed 10 Feb 2020.

Parliament of Australia. New mobile clinic receives support from the Australian Government. Canberra: Parliament of Australia; 2014. Available from: https://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/search/display/display.w3p;query=Id:%22media/pressrel/3460433%22. Accessed 10 Feb 2020.

University of Queensland. Mobile Indigenous health clinic reaches out to underserviced communities. Brisbane: The University of Queensland; 2013. Available from: https://www.uq.edu.au/news/article/2013/02/mobile-indigenous-health-clinic-reaches-out-underserviced-communities. Accessed 10 Feb 2020.

Carbal Medical Services. Health Service Programs. Toowoomba: Carbal Medical Services; 2019. Available from: https://carbal.com.au/health-service-programs/. Accessed 10 Feb 2020.

Carbal Medical Services. Annual Report. Toowoomba; Carbal Medical Services; 2014. p. 5–15.

Ballestas T, McEvoy S, Swift-Otero V, Unsworth M. A metropolitan Aboriginal podiatry and diabetes outreach clinic to ameliorate foot-related complications in Aboriginal people. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2014;38(5):492–3.

Bestel M. Ancient art delivers modern health advice. Aust Nurs J. 2010;18(6):42–3.

Sinclair C, Stokes A, Jeffries-Stokes C, Daly J. Positive community responses to an arts-health program designed to tackle diabetes and kidney disease in remote Aboriginal communities in Australia: a qualitative study. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2016;4:307–12.

Jeffries-Stokes C. The Western Desert kidney health project. University of Western Australia 2017. Available from: https://api.research-repository.uwa.edu.au/portalfiles/portal/14204754/THESIS_DOCTOR_OF_PHILOSOPHY_JEFFRIES_STOKES_Christine_Andrea_2017.pdf. Accessed 3 Jan 2020.

Burgess S, Buchanan K. Mobile health clinic to help boost Indigenous health [internet]. ABC News; 2013. Available from: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2013-06-04/mobile-health-clinic-to-help-boost-indigenous-health/4731474. Accessed 3 Jan 2020.

Goondir Health Services. Mobile Health Promotion Van. Dalby: Goondir Health Services; 2020. Available from: https://www.goondir.org.au/service/mobile-health-promotion-van. Accessed 5 Feb 2020.

Goondir Health Services. Goondir Health Services Annual Report 2017–2018. Dalby: Goondir Health Services; 2019. Available from: https://www.goondir.org.au/pdfs/Goondir_Health_Services_Annual_Report_2017_2018_V17_WEB.pdf. Accessed 6 Mar 2020.

Earbus Foundation of WA. Earbus program. Northbridge: Earbus Foundation of WA; 2020. Available from: http://www.earbus.org.au/earbus-program. Accessed 4 Feb 2020.

Earbus Foundation of WA. 2018 Annual report. Northbridge: Earbus Foundation of WA; 2018. Available from: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/551ccb22e4b020e4eeaff320/t/5d27ed6d52233900019570f5/1562897916699/AR18+-+Web+version.pdf. Accessed 4 Feb 2020.

Telethon Speech & Hearing. Chevron Pilbara Ear Health Program. Wembley: Telethon Speech & Hearing; 2020. Available from: https://www.tsh.org.au/programs-services/chevron-pilbara-ear-health-program/. Accessed 10 Feb 2020.

Higginbotham P. Otitis media in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in Western Australia: analyses of recent data of the Telethon Speech and Hearing mobile ear clinic program. Presented: Australian Otitis Media Conference. Fremantle; 2012.

Krishnaswamy J, Monley P, Kishida Y. Optimising Children's Specialist Ear Health Clinic Attendance Rates in Rural and Remote ATSI Communities. Presented: Aboriginal Health Conference: Healthy Families - Healthy Futures. Perth; 2015.

Telethon Speech & Hearing. Annual Report 2018. Wembley: Telethon Speech & Hearing; 2019. Available from: https://www.tsh.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/TSH-Annual_Report-2018-FINAL7_WEB.pdf. Accessed 5 Feb 2020.

Evins B. Colourful health bus provides medical services to Aboriginal and Torres Strait islanders in remote areas. Ultimo: ABC Riverland; 2018. Design, implementation and results of a mobile clinic-based diabetes screening program from India.

Geraldton Regional Aboriginal Medical Service. Mobile Clinic. Geraldton: Geraldton Regional Aboriginal Medical Service; 2020. Available from: https://www.grams.asn.au/murchison-outreach-service.aspx. Accessed 4 Feb 2020.

Nhulundu Health Service. Nhulundu expands services to Biloela. Gladstone: Nhulundu Health Service; 2016. Available from: https://www.nhulundu.com.au/biloela/. Accessed 4 Feb 2020.

Jin A. Aboriginal diabetes initiative (ADI) funded Mobile screening and management projects - synthesis report Surrey. British Columbia: Health Canada; 2014. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/320386708_Aboriginal_Diabetes_Initiative_ADI_funded_Mobile_Screening_and_Management_Projects_-_Synthesis_Report. Accessed 10 Feb 2020.

Oster RT, Virani S, Strong D, Shade S, Toth EL. Diabetes care and health status of first nations individuals with type 2 diabetes in Alberta. Can Fam Physician. 2009;55(4):386–93.

Virani S, Strong D, Tennant M, Greve M, Young H, et al. Rationale and implementation of the SLICK project: screening for limb, I-eye, cardiovascular and kidney (SLICK) complications in individuals with type 2 diabetes in Alberta's first nations communities. Can J Public Health. 2006;97(3):241–7.

Ralph-Campbell K, Oster RT, Connor T, Pick M, Pohar S, Thompson P, et al. Increasing rates of diabetes and cardiovascular risk in Métis settlements in northern Alberta. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2009;68(5):433–42.

Oster RT, Ralph-Campbell K, Connor T, Pick M, Toth EL. What happens after community-based screening for diabetes in rural and Indigenous individuals? Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;88(3):28–31.

Ralph-Campbell K, Oster R, Conner T, Toth E. Emerging longitudinal trends in health indicators for rural residents participating in a diabetes and cardiovascular screening program in northern Alberta, Canada. Int J Fam Med. 2011;2011:1–6.

Toth E. Mobile diabetes screening initiative through the years [internet]. MDSi wrap up meeting: 2014. Available from: https://mdsiblog.files.wordpress.com/2014/11/elt-smdi-slides-1.pdf. Accessed 6 Feb 2020.

First Nations Health Authority. Warriors meet again. Vancouver: First Nations Health Authority; 2019. Available from: https://www.fnha.ca/wellness/sharing-our-stories/warriors-meet-again. Accessed 4 Feb 2020.

Dawson K, Maberley DAL, Martin JD, Hyslop W, Jin A. Mobile diabetes telemedicine clinic (MDTC): role in first nations care and treatment. Can J Diabetes. 2009;33(3):195.

Carrier Sekani Family Services. MDTC Pamphlet. Prince George: Carrier Sekani Family Services; 2020. Available from: https://www.csfs.org/services/mobile-diabetes. Accessed 12 Feb 2020.

Roubidoux MA, Shih-Pei Wu P, Nolte ELR, Begay JA, Joe AI. Availability of prior mammograms affects incomplete report rates in mobile screening mammography. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2018;3:667–73.

Roen EL, Roubidoux MA, Joe AI, Russell TR, Soliman AS. Adherence to screening mammography among American Indian women of the northern plains. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;3:897–905.

Rural Health Information Hub. Mobile Women's health unit. Grand Forks: Rural Health Information Hub; 2019. Available from: https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/project-examples/494. Accessed 10 Feb 2020.

Indian Health Service. Office of Health Programs. Rockville: Indian Health Service; 2020. Available from: https://www.ihs.gov/greatplains/programs/officeofhealthprograms/. Accessed 5 Feb 2020.

Mobile Healthcare Association. Native American National Coalition Coordinators. St. Louis: Mobile Healthcare Association; 2020. Available from: http://www.mobilehca.org/regnativeorgs.html. Accessed 7 Feb 2020.

Bylander J. Propping up Indian health care through Medicaid. Health Aff. 2017;36(8):1360–4.

Tuba City Regional Health Care Corporation. Community Health Center – Mobile Health Program. Tuba City: Tuba City Regional Health Care Corporation; 2019. Available from: https://www.tchealth.org/mobilehealth/index.html. Accessed 9 Feb 2020.

Winslow Indian Health Care Center. WIHCC Gets A New Medical Mobile Vehicle. Winslow: Winslow Indian Health Care; 2020. Available from: https://www.wihcc.com/new-medical-vehicle.html#. Accessed 7 Feb 2020.

Bay Clinic. Mobile health unit. Hilo: Bay Clinic; 2020. Available from: https://www.bayclinic.org/locations/administrative-office-2. Accessed 12 Feb 2020.

Mni Wiconi Clinic and Farm. Our Programs: Mni Wiconi Clinic and Farm; 2019. Available from: https://www.mniwiconiclinicandfarm.org/programs. Accessed 12 Feb 2020.

Children’s Health Fund. First Pediatric Mobile Clinic in Indian Country to Deliver Vital Services to Ho-Chunk Nation's Medically Underserved Children. New York: PR Newswire; 2012. Available from: https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/first-pediatric-mobile-clinic-in-indian-country-to-deliver-vital-services-to-ho-chunk-nations-medically-underserved-children-167039205.html. Accessed 12 Feb 2020.

Government of Canada. Canada’s Health Care System. Ontario: Government of Canada; 2019. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/health-care-system/reports-publications/health-care-system/canada.html. Accessed 5 Jan 2020.

Australian Government Department of Health. The Australian Health System. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health; 2019. Available from: https://www.health.gov.au/about-us/the-australian-health-system. Accessed 5 Mar 2020.

Ministry of Health. Overview of the health system. Wellington: Ministry of Health; 2017. Available from: https://www.health.govt.nz/new-zealand-health-system/overview-health-system. Accessed 5 Mar 2020.

Rosenbaum S. The patient protection and affordable care act: implications for public health policy and practice. Public Health Rep. 2011;126(1):130–5.

Dwyer J, Boulton A, Lavoie JG, Tenbensel T, Cumming J. Indigenous peoples’ health care: new approaches to contracting and accountability at the public administration frontier. Public Manag Rev. 2014;16(8):1091–112.

Lavoie JG, Kornelsen D, Wylie L, Mignone J, Dwyer J, Boyer Y, et al. Responding to health inequities: Indigenous health system innovations. Global Health, Epidemiology and Genomics; 2016. https://doi.org/10.1017/gheg.2016.12.

Lavoie JG, Boulton AF, Gervais L. Regionalization as an Opportunity for Meaningful Indigenous Participation in Healthcare: Comparing Canada and New Zealand. Int Indigenous Policy J. 2012. https://doi.org/10.18584/iipj.2012.3.1.2.

Australian Government Department of Health. Modified Monash Model [Internet]. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health; 2020. Available from: https://www.health.gov.au/health-workforce/health-workforce-classifications/modified-monash-model. Accessed 5 Apr 2020.

Australian Government Department of Health. Rural Health Multidisciplinary Training (RHMT) Program. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health; 2020. Available from: https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/rural-health-multidisciplinary-training. Accessed 11 Mar 2020.

Harfield SG, Davy C, McArthur A, Munn Z, Brown A, Brown N. Characteristics of Indigenous primary health care service delivery models: a systematic scoping review. Glob Health. 2018;14(1):1–11.

Naqshbandi M, Harris SB, Esler JG, Antwi-Nsiah F. Global complication rates of type 2 diabetes in Indigenous peoples: a comprehensive review. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2008;82(1):1–17.

Jervis-Bardy J, Sanchez L, Carney AS. Otitis media in Indigenous Australian children: review of epidemiology and risk factors. J Laryngol Otol. 2014;128(Suppl 1):16–27.

Beks H, Binder MJ, Kourbelis C, Ewing G, Charles J, Paradies Y, et al. Geographical analysis of evaluated chronic disease programs for Aboriginal and Torres Strait islander people in the Australian primary health care setting: a systematic scoping review. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1–17.

Chino M, DeBruyn L. Building true capacity: Indigenous models for Indigenous communities. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(4):596–9.

Smylie J, Kirst M, McShane K, Firestone M, Wolfe S, O'Campo P. Understanding the role of Indigenous community participation in Indigenous prenatal and infant-toddler health promotion programs in Canada: a realist review. Soc Sci Med. 2016;150(1):128–43.

Lokuge K, Thurber K, Calabria B, Davis M, McMahon K, Sartor L, et al. Indigenous health program evaluation design and methods in Australia: a systematic review of the evidence. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2017;41(5):480–2.

Derrick GE, Hayen A, Chapman S, Haynes AS, Webster BM, Anderson I. A bibliometric analysis of research on Indigenous health in Australia, 1972-2008. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2012;36(3):269–73.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the contribution of Deakin University librarians Rebecca Muir, Fiona Russell and Blair Kelly, in providing guidance on the development of the initial search strategy and use of academic databases and information sources. We also acknowledge the role of Budja Budja Aboriginal Cooperative (Halls Gap, Victoria, Australia), including Chief Executive Officer, Tim Chatfield, Djab Wurrung man, and Independent Director and Secretary, Roman Zwolak, in assisting with formulating the review question. This systematic scoping review was undertaken as part of Hannah Beks’ thesis, in order to fulfil the requirements of the Doctor of Philosophy (PhD).

Funding

No funding was received for this review. Robyn A Clark is supported by a Heart Foundation Future Leader Fellowship (APP ID. 100847). Hannah Beks, Geraldine Ewing, and Vincent L Versace are funded by the Australian Government Department of Health Rural Health Multidisciplinary Training (RHMT) Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HB led the scoping review design, screening of data, data extraction, analysis of data, and drafting of the manuscript. GE was involved in the scoping review design, screening of data, data extraction, analysis of data and drafting of the manuscript. RC and VLV were involved in the scoping review design, analysis of data and drafting of the manuscript. VLV produced the geographical outputs and analysis. JC, FM and YP were involved in the analysis of data, and drafting of the manuscript which included a review for cultural appropriateness in the reporting of outcomes. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Beks, H., Ewing, G., Charles, J.A. et al. Mobile primary health care clinics for Indigenous populations in Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States: a systematic scoping review. Int J Equity Health 19, 201 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-020-01306-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-020-01306-0