Abstract

Background

The prevalence of smoking during pregnancy among indigenous women approaches 50% and is associated with sudden infant death, pregnancy loss, preterm delivery, low birth weight, and anatomical deformity. This study aims to synthesise qualitative studies by reporting experiences, perceptions, and values of smoking cessation among pregnant indigenous women to inform potential interventions.

Method

A highly-sensitive search of MEDLINE, Embase, PsychINFO, and CINAHL, in conjunction with analysis of Google Scholar and reference lists of related studies was conducted in March 2018. We utilised two methods (thematic synthesis and an indigenous Māori analytical framework) in parallel to analyse data. Completeness of reporting in studies was evaluated using the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Studies (COREQ) framework.

Results

We included seven studies from Australia and New Zealand involving 250 indigenous women. Three themes were identified. Realising well-being and creating agency included giving the best start to baby, pride in being a healthy mum, female role models, and family support. Understanding the drivers for smoking included the impact of stress and chaos that hindered prioritisation of self-care, the social acceptability of smoking, guilt and feeling judged, and inadequate information about the risks of smoking. Indigenous women strongly preferred culturally responsive approaches to smoking cessation, placing value on programs designed specifically for and by indigenous people, that were accessible, and provided an alternative to smoking.

Conclusion

Future interventions and smoking cessation programmes might be more effective and acceptable to indigenous women and families when they harness self-agency and the desire for a healthy baby, recognise the high value of indigenous peer involvement, and embed a social focus in place of smoking as a way to maintain community support and relationships. Development and evaluation of smoking cessation programs for pregnant indigenous women and families is warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

About one in eight non-indigenous women smoke during pregnancy, while almost half of indigenous women smoke while pregnant [1,2,3,4]. Smoking in pregnancy increases pregnancy and neonatal complications including miscarriage, pre-term delivery, placental complications, low birth weight, and anatomical abnormalities [5, 6]. Smoking during pregnancy is a major risk factor for sudden unexpected death in infancy (SUDI), particularly when associated with infant bed sharing [7, 8] and this is well noted among indigenous babies [8,9,10,11].

Many smoking cessation initiatives have been developed to decrease smoking in pregnancy [12,13,14,15,16], including interventions specifically for indigenous women [14, 17]. Despite these interventions and related policies, programmes, and regulations, smoking among indigenous women remains a serious health problem internationally. Effective health interventions require an understanding of the social context of the problem and of the target audience. Understanding therefore, the experiences and values of indigenous women is crucial to ensuring that future interventions and policy better align with the preferences of indigenous women for smoking cessation. To date, many women have reported wanting to stop smoking but feeling unable to quit, being unaware of services or finding them difficult to access, and expressing concerns about being stigmatised once identified as a smoker [18,19,20].

This systematic review of qualitative studies aims to describe indigenous women’s experiences, perceptions, and values related to stopping smoking in pregnancy in order to inform the development of programs and interventions that respond to the needs, concerns and preferences of indigenous women.

Methods

Searches

Highly-sensitive searches were conducted in MEDLINE, Embase, PsychINFO, and CINAHL, from January 1, 2000 to March 1, 2018 Google Scholar and reference lists of related studies and reviews were also searched. Two authors (RCW, AJ) screened initial search results of titles and abstracts independently and excluded those that did not meet the review eligibility criteria. Full texts of potentially relevant articles were then screened by all authors.

Study inclusion and exclusion criteria

Qualitative studies were eligible if they reported qualitative data about smoking cessation in pregnancy through interviews, focus groups, or other responses (e.g. diaries, observation) involving indigenous women. We included studies involving indigenous women from New Zealand, Australia, Canada, Taiwan, and the United States. Studies were ineligible if they solely included women who were not pregnant, not identified as indigenous, or did not address smoking cessation. Studies reporting structured questionnaires or surveys as the sole method for data collection or quantitative data were ineligible. Studies that did not elicit data directly from indigenous women as consumers were also excluded.

Study quality assessment

This thematic synthesis is reported according to the Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research (ENTREQ) statement [21]. Thematic synthesis aims to provide an over-arching conceptual understanding of a topic through the systematic examination of the content and overlap provided in available qualitative studies. Completeness of methodological reporting was assessed independently by two researchers (RCW and AG) using the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) checklist [22]. The COREQ checklist includes domains to evaluate reporting of the research team and reflexivity, study design, and data analysis and reporting, to provide an assessment of the transferability of the primary study to a specific research setting.

Data synthesis and presentation

We used two methods of data analysis in parallel. The first author used thematic synthesis as described by Thomas and Harden [23]. The second author applied an indigenous Māori analytical framework to examine the findings, employing a series of lenses derived from distinctive cultural epistemologies [24] framed around an indigenous model called Te Whetu that is based on five interconnected aspects (mind, body, spirit, family and land) [25]. This thematic analysis then included indigenous interpretations and description of findings, ensuring that they were robust from a cultural perspective.

Participant quotations and text under the “Results/Findings” or “Conclusion/Discussion” section of each study was imported into HyperRESEARCH (ResearchWare, INC 2009, version 3.0.3) software. Two authors (RCW and AG) then independently performed line-by-line coding of the findings of the primary studies, conceptualized the data, and inductively identified concepts using the two different frameworks. Concepts were then together grouped into agreed themes with subthemes. The second stage was to identify conceptual links among subthemes and themes (by RCW and AG) using a mind mapping approach to extend the findings offered by the primary studies and to develop an analytical thematic schema. Researcher triangulation was used, in which all authors independently reviewed the preliminary themes and analytical frameworks and discussed the addition or revision of themes amongst the research team.

Results

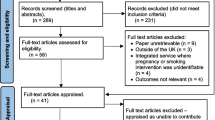

The search identified 485 unique records (Fig. 1). Of these, seven studies involving 250 pregnant indigenous women were included (Fig. 1). Four studies (57%) were from Australia, and three (two reporting from the same study) were conducted in New Zealand (43%). The participants’ age ranged from 14 to 53 years. Four studies involved face to face interviews, two used focus groups, and one study involved both methodologies (Table 1).

The comprehensiveness of reporting varied across the included studies (Table 2). The relationship established between the researchers and participants, member checking and whether repeat interviews were conducted was not described in any studies. Methods for recruiting women, the sample size, and participant quotations were reported in all seven studies. Two studies reported the presence of data saturation, field notes, and the duration of interviews.

Synthesis

Three themes were identified as central to indigenous women’s perspectives of smoking in pregnancy: realising well-being and creating agency, understanding the drivers for smoking, and appreciating culturally responsive approaches. The subthemes are described below, and we have indicated where possible, if findings were specific to a particular population or setting. Table 3 includes a selection of participant quotations and explanations provided by the authors to illustrate each theme.

Realising well-being and creating agency

Giving the best start to baby

Many women prioritised stopping smoking “so my baby would be healthy” once learning they were pregnant. The health of their baby was a paramount consideration despite experiencing difficulty stopping smoking. “I gave up smoking when I was about 7 months, it was hard for me but I just thought of my baby” [26]. Retrospectively, women who were not aware of the harms of smoking during pregnancy were grateful that they did stop.

Pride in being a healthy mum

Some women wanted to be smoke-free because this would mean that they themselves would be a healthier and therefore better mum; “I would have a lot more energy, and be able to do more things with my son and not be puffed” [27]. One women acknowledged that now as a mum she would be a role model for her child and “wouldn’t want them to think it is OK to smoke” [27]. Another mum felt a sense of needing to keep herself well in order to “see them grow up” [27]. Reducing the number of smokes or becoming smoke-free also instilled pride and confidence that they were making positive changes for themselves and baby.

Influence of female role models

The importance of other women to smoking cessation, particularly as positive role models “to support, praise, awhi (support) women” [28] was evident in the women’s experiences. This support gave women “confidence in myself, that I knew I could do it” [27]. The influence of indigenous women to stop smoking was valued higher than medical advice. “I have nothing but the utmost respect for my aunt whereas the doctor is just another Joe Blow” [29].

Importance of family support

Having encouragement and support from family and partners to stop smoking was a critical factor in women successfully becoming smoke-free during pregnancy. Being reminded to “think of the baby” [30], and positive messages encouraged self-belief. Some women told of how their partner trying to give up at the same time helped them to stay motivated and committed. In contrast to these experiences, other women expressed how hard it was when their “families won’t support you to quit because theytoo busy smoking themselves. They encourage your smoking even more” [31]. Some women’s families also directly disregarded their attempts to stop smoking by “saying, ‘no you’s can’t do it” [26] leading to self-doubt in their ability to stop.

Understanding the drivers for smoking

Impact of stress and chaos

Many women identified competing issues that impeded their attempts to quit smoking while pregnant. Stress, difficult relationships and times of chaos within the women’s lives impacted on their capacity to prioritise smoking cessation. “I knew it wasn’t good for me and baby at the time, but like it was more stress … because I had so much of it, I just didn’t care what I was doing at the time” [27]. Smoking was also identified as self-medication to manage stress. One women described that smoking “stops me from stressing out, stops me from worrying about things” [30].

Social acceptability of smoking

Women spoke of their strong connection to their wider family and community and how within their indigenous community, smoking was acceptable and a lower health priority for them and their baby. Their role as a smoker gave them a sense of belonging and connection, they were concerned about social isolation if they stopped smoking.

Guilt and feeling judged

Guilt for some women “made me quit” [26], whereas others felt guilty that they “should be able to just stop for the health of my baby, but I just can’t” [26]. This led to women feeling ashamed and hiding that they smoked. Women felt guilt and regret that their smoking was the potential cause of their baby’s health problems. “my last one [pregnancy] was very traumatic just due to smoking, all my pregnancies were difficult due to my smoking” [31].

Inadequate information about smoking risks

Many women were uncertain of the risks to their baby during pregnancy and had received conflicting information. Women in many studies cited the biggest risk of smoking as “it makes baby small” [31], however some saw this as an advantage, particularly when they were warned about the risks of big babies in diabetic pregnancies, “oh I can’t quit because I am having a bigger baby or I want the baby to be small” [26]. In one Australian study, women reported not being told to quit smoking during pregnancy, but “only to reduce their intake” [29]. A common theme throughout studies was the belief cutting down the number they smoked or having breaks throughout pregnancy without smoking would be better for baby. Women reported receiving conflicting information about the risks of smoking cessation aids including nicotine replacement therapy and “the effect on baby” [28]. Many women reflected that if they had known earlier that they were doing harm to their baby, then they would have been more committed to stopping smoking “I had no signs of an unhealthy baby, so I continued to smoke” [27].

Culturally responsive approaches

Valuing indigenous programs

Women reported current smoking cessation programs did not meet their values and preferences, recommending programs needed to be “more one on one” [29] with people who understood their background and “where the smoker is coming from” [28]. Women valued care from indigenous health workers and education and support involving “all the whānau (family)” [28]. Family-based care strengthened the impact of knowledge “the more we know, the more knowledge we have and we can share it with other people” [28]. Women recommended methods of delivery of education such as “yarning”, or visual, or “via music, listening to lyrics to do with stop smoking” [28].

Improving accessibility of programs

Smoking cessation programs were experienced as inaccessible and impersonal and failed to deliver care “I felt too disconnected from my support and they didn’t ring as promised” [28]. Some women described the benefit of out-reach services, “some people don’t have a phone and the fact that the service came to my home at a time convenient to me is a huge bonus, made it easier for me not to avoid” [28]. The lack of subsidisation and wide availability of nicotine replacement therapy prevented use [28]. Women suggested that there needed to be more advertising and campaigns about the risks of smoking during pregnancy and how to access support to quit.

Needing something to replace smoking

Some women wanted there to be more to smoking programs than just smoking cessation advice, and include support for their overall well-being. Women identified smoking as an activity that built social connections, which highlighted the opportunity to use other joint activities to build and maintain social relationships; “I reckon if we had something to do, you know like keep us busy, take our mind off smoking, like arts and craft” [31]. Women found hearing advice from others on ways “they cope with it is helpful” [29]. Women experienced being more isolated and less distracted when pregnant. This gave more time to think about smoking and made it harder to stop; “if you do other stuff, you’re not going to worry about it, so that’s how you cut down” [31].

Discussion

This systematic review has synthesised perspectives, attitudes, expectations, and experiences of indigenous women from qualitative research investigating smoking cessation in pregnancy. We found only seven eligible studies involving 250 indigenous women from Australia and New Zealand. We had also searched for studies from Canada, Taiwan and the United States - developed countries where the indigenous peoples have been colonised and where we might have expected to see some common experience with widespread social and socio-economic marginalisation, and gross health inequities [32]. Despite those similarities there are vast differences in delivery of health services between and within these countries, ranging from mainstream services who are generally unable to meet indigenous need to indigenous health care systems that are under-resourced and struggle to cope with demand [33]. The delivery of smoking cessation programs is similarly diverse.

We identified three central themes across these services. First, realising well-being and creating agency were expressed as giving the best start to baby, pride in being a healthy mum, and the importance of female role models and family support. Second, understanding the drivers for smoking included the impact of the stress and chaos indigenous women often experience in their lives, the relative social acceptability of smoking within indigenous communities, the pervasive forces of guilt and judgment and the lack of information and knowledge to support decision-making. Finally, the women identified their appreciation for culturally responsive approaches to cessation valuing programs designed specifically for and by indigenous people that were easily accessible and that acknowledged the need for programs to provide an alternative to smoking.

These findings broadly reflect those found in a systematic review of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women [34] in which social norms and stressors within the Aboriginal community perpetuated tobacco use and there was insufficient knowledge provided to smokers in ways that supported smoking cessation. Another systematic review also indicated that community-based knowledge of the harmful effects of smoking did not translate into smoking cessation [35]. The findings in the present systematic review suggest that this knowledge might be effectively translated by building on the self-agency and determination of woman to have a healthy baby, be healthy mums and incorporating the views of influential female peers into programs. Our review indicates that current smoking cessations programs need to be closer aligned to the values of indigenous women and communities.

Other studies have reported the challenges faced by health professionals to delivering smoking cessation advice and care during pregnancy [36, 37]. Lack of support from health professionals has previously been reported as a common barrier to smoking cessation during pregnancy and for indigenous peoples, the pervasive effect of cultural and historical norms [38].

Women in these studies experienced receiving inconsistent information and education from health care professionals and others in their community, as has been previously described [35]. This inconsistency in information caused confusion and doubt about the potential harms of smoking, especially if women had known of other “healthy” babies whose mothers had smoked. Women also recommended programs would be more successful if they helped them to address some of the wider issues that led to their smoking and also include other activities that replaced smoking and strengthened a sense of community. Acknowledging the absence of evidence to support smoking cessation in pregnant Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women, Gould [40] developed a pragmatic guidance for health practitioners that includes: screening the patient, counselling, initiation of NRT, making a personal Quit Plan, follow-up support, and utilising ancillary resources. Although this guide may respond to some needs, we recommend a more culturally responsive approach that includes collaboration and partnership with indigenous people built on cultural values. This approach has been successful in New Zealand in the Safe Sleep SUDI prevention programme designed around Safe Sleep devices that were able to be deployed in the shared bed to prevent sudden infant death [41, 42]. This program utilised traditional crafts (weaving with flax) to support a traditional value (bed-sharing) that was widely supported by Māori women elders in the creation of this safe infant sleep space and thus addressing cultural needs and increasing support available to new mothers. The findings of this review suggest that this kind of cultural resonance and support is needed for smoking cessation during pregnancy developing a culturally meaningful and accessible programme that provides support and is empowering of pregnant indigenous women.

Understanding successful interventions and linking these to the results of this review will help to build stronger smoking cessation programs that specifically target indigenous women. Future research should include the development of smoking cessation programs built on successful interventions that align with the findings of this review.

Conclusions

Future interventions and smoking cessation programmes might be more effective and acceptable to indigenous women and families when they harness self-agency and the desire for a healthy baby, recognise the high value of culturally responsive approaches and indigenous peer involvement and embed a social focus in place of smoking as a way to maintain community support and relationships. Development and evaluation of smoking cessation programs for pregnant indigenous women and families is warranted.

References

Heaman MI, Chalmers K. Prevalence and correlates of smoking during pregnancy: a comparison of aboriginal and non-aboriginal women in Manitoba. Birth. 2005;32(4):299–305.

Passey ME, Bryant J, Hall AE, Sanson-Fisher RW. How will we close the gap in smoking rates for pregnant Indigenous women?. The Medical Journal of Australia. 2013;199(1):39–41.

Health UDo, Services H. The health consequences of smoking: a report of the surgeon general. 2004.

Tipene-Leach D, Hutchison L, Tangiora A, Rea C, White R, Stewart A, et al. SIDS-related knowledge and infant care practices among Maori mothers. NZ Med J. 2010;123(1326):88–96.

Castles A, Adams EK, Melvin CL, Kelsch C, Boulton ML. Effects of smoking during pregnancy: five meta-analyses. Am J Prev Med. 1999;16(3):208–15.

Hammoud AO, Bujold E, Sorokin Y, Schild C, Krapp M, Baumann P. Smoking in pregnancy revisited: findings from a large population-based study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192(6):1856–62.

Fleming P, Blair PS. Sudden infant death syndrome and parental smoking. Early Hum Dev. 2007;83(11):721–5.

Mitchell EA, Thompson JM, Zuccollo J, MacFarlane M, Taylor B, Elder D, et al. The combination of bed sharing and maternal smoking leads to a greatly increased risk of sudden unexpected death in infancy: the New Zealand SUDI Nationwide Case Control Study. N Z Med J. 2017;130(1456):52.

Hauck F, Tanabe K, Moon R. Racial and ethnic disparities in infant mortality. Semin Perinatol. 2011;35(4):209–220.

Collins SA, Surmala P, Osborne G, Greenberg C, Bathory LW, Edmunds-Potvin S, et al. Causes and risk factors for infant mortality in Nunavut, Canada 1999-2011. BMC Pediatr. 2012;1(12):190.

Freemantle CJ, Read AW, de Klerk NH, McAullay D, Anderson IP, Stanley FJ. Patterns, trends, and increasing disparities in mortality for aboriginal and non-aboriginal infants born in Western Australia, 1980–2001: population database study. Lancet. 2006;9524(367):1758–66.

Lumley J, Oliver S, Waters E. Interventions for promoting smoking cessation during pregnancy. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2000;(2):CD001055-CD001055.

Ussher M, Lewis S, Aveyard P, Manyonda I, West R, Lewis B, et al. Physical activity for smoking cessation in pregnancy: randomised controlled trial. bmj. 2015;350:h2145.

Ivers RG. An evidence-based approach to planning tobacco interventions for Aboriginal people. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2004;23(1):5–9.

Hubbard G, Gorely T, Ozakinci G, Polson R, Forbat L. A systematic review and narrative summary of family-based smoking cessation interventions to help adults quit smoking. BMC Fam Pract. 2016;17(1):73.

Chamberlain C, Perlen S, Brennan S, Rychetnik L, Thomas D, Maddox R, et al. Evidence for a comprehensive approach to aboriginal tobacco control to maintain the decline in smoking: an overview of reviews among indigenous peoples. Syst Rev. 2017;6(1):135.

Glover M, Kira A, Walker N, Bauld L. Using incentives to encourage smoking abstinence among pregnant indigenous women? A feasibility study. Matern Child Health J. 2015;19(6):1393–9.

Roddy E, Antoniak M, Britton J, Molyneux A, Lewis S. Barriers and motivators to gaining access to smoking cessation services amongst deprived smokers–a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6(1):147.

Shipton D, Tappin DM, Vadiveloo T, Crossley JA, Aitken DA, Chalmers J. Reliability of self reported smoking status by pregnant women for estimating smoking prevalence: a retrospective, cross sectional study. Bmj. 2009;339:b4347.

Tod AM. Barriers to smoking cessation in pregnancy: a qualitative study. Br J Community Nurs. 2003;8(2):56–64.

Tong A, Flemming K, McInnes E, Oliver S, Craig J. Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12(1):181.

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–57.

Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8(1):45.

Tonu AGT. Young Māori Mothers' experiences of wellbeing surrounding the birth of their first Tamaiti. Wellington: Vicotria University; 2018.

Mark GT, Lyons AC. Maori healers' views on wellbeing: the importance of mind, body, spirit, family and land. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(11):1756–64.

Gould GS, Munn J, Avuri S, Hoff S, Cadet-James Y, McEwen A, et al. “Nobody smokes in the house if there's a new baby in it”: aboriginal perspectives on tobacco smoking in pregnancy and in the household in regional NSW Australia. Women Birth. 2013;26(4):246–53.

Gould GS, Bovill M, Clarke MJ, Gruppetta M, Cadet-James Y, Bonevski B. Chronological narratives from smoking initiation through to pregnancy of indigenous Australian women: a qualitative study. Midwifery. 2017;52:27–33.

Glover M, Kira A. Pregnant Māori smokers’ perception of cessation support and how it can be more helpful. J Smok Cessat. 2012;7(2):65–71.

Bovill M, Gruppetta M, Cadet-James Y, Clarke M, Bonevski B, Gould G. Wula (voices) of aboriginal women on barriers to accepting smoking cessation support during pregnancy: findings from a qualitative study. Women Birth. 2018;31(1):10–6.

Glover M, Kira A. Why Maori women continue to smoke while pregnant. N Z Med J. 2011;124:1339.

Wood L, France K, Hunt K, Eades S, Slack-Smith L. Indigenous women and smoking during pregnancy: knowledge, cultural contexts and barriers to cessation. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(11):2378–89.

Gracey M, King M. Indigenous health part 1: determinants and disease patterns. Lancet. 2009;374(9683):65–75.

Harfield SG, Davy C, McArthur A, Munn Z, Brown A, Brown N. Characteristics of indigenous primary health care service delivery models: a systematic scoping review. Glob Health. 2018;14(1):12.

Gould GS, Munn J, Watters T, McEwen A, Clough AR. Knowledge and views about maternal tobacco smoking and barriers for cessation in aboriginal and Torres Strait islanders: a systematic review and meta-ethnography. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;15(5):863–74.

Ingall G, Cropley M. Exploring the barriers of quitting smoking during pregnancy: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Women Birth. 2010;23(2):45–52.

Okoli CT, Greaves L, Bottorff JL, Marcellus LM. Health care providers' engagement in smoking cessation with pregnant smokers. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2010;39(1):64–77.

Baxter S, Everson-Hock E, Messina J, Guillaume L, Burrows J, Goyder E. Factors relating to the uptake of interventions for smoking cessation among pregnant women: a systematic review and qualitative synthesis. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12(7):685–94.

Twyman L, Bonevski B, Paul C, Bryant J. Perceived barriers to smoking cessation in selected vulnerable groups: a systematic review of the qualitative and quantitative literature. BMJ Open. 2014;4(12):e006414.

Glover M, Nosa V, Gentles D, Watson D, Paynter J. Do New Zealand Māori and Pacific ‘walk the talk’when it comes to stopping smoking? A qualitative study of motivation to quit. Journal of Smoking Cessation. 2014;9(2):68–75.

Gould GS, Bittoun R, Clarke MJ. A pragmatic guide for smoking cessation counselling and the initiation of nicotine replacement therapy for pregnant aboriginal and Torres Strait islander smokers. J Smok Cessat. 2015;10(2):96–105.

Mitchell EA, Cowan S, Tipene-Leach D. The recent fall in postperinatal mortality in New Zealand and the safe sleep programme. Acta Paediatr. 2016;105(11):1312–20.

Abel S, Tipene-Leach D. SUDI prevention: a review of Maori safe sleep innovations for infants. N Z Med J. 2013;126:1379.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Funding

No funding received for this study.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Research idea and study design: RCW, SP, DTL; data acquisition: RCW, AG; data analysis/interpretation: all authors; All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Walker, R.C., Graham, A., Palmer, S.C. et al. Understanding the experiences, perspectives and values of indigenous women around smoking cessation in pregnancy: systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Int J Equity Health 18, 74 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-019-0981-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-019-0981-7