Abstract

Introduction

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in Australia experience a higher prevalence of disability and socio-economic disadvantage than other Australian children. Early intervention is vital for improved health outcomes, but complex and fragmented service provision impedes access. There have been international and national policy shifts towards inter-sector collaborative responses to disability, but more needs to be known about how collaboration works in practice.

Methods

A systematic integrative literature review using a narrative synthesis of peer-reviewed and grey literature was undertaken to describe components of inter- and intra-sector collaborations among services to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children with a disability and their families. The findings were synthesized using the conceptual model of the ecological framework.

Results

Thirteen articles published in a peer-reviewed journal and 18 articles from the grey literature met inclusion criteria. Important factors in inter- and intra-sector collaborations identified included: structure of government departments and agencies, and policies at the macro- (government) system level; communication, financial and human resources, and service delivery setting at the exo- (organizational) system level; and relationships and inter- and intra-professional learning at the meso- (provider) system level.

Conclusions

The policy shift towards inter-sector collaborative approaches represents an opportunity for the health, education and social service sectors and their providers to work collaboratively in innovative ways to improve service access for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children with a disability and their families. The findings of this review depict a national snapshot of collaboration, but as each community is unique, further research into collaboration within local contexts is required to ensure collaborative solutions to improve service access are responsive to local needs and sustainable.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In contrast to other countries, the Australian population has access to a first-class universal healthcare system and is relatively healthy [1]. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are an exception to this rule. The gap in health outcomes and life expectancy between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and other Australians has been widely reported [1]–[3]. The rate of death for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children is more than twice that for other children [2]. This disparity in health outcomes extends to disability [4]. Increasingly there is recognition of the importance of the social determinants of health and of health as a human right.

Social determinants of health and human rights

Although there are social gradients in the incidence of disability, it is reported that little attention has been paid to research on the social determinants of health in disability policy [5]. Policy has the potential to act as a structural determinant of health [6]. The Australian Human Rights Commission has drawn attention to a number of human rights violations faced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander persons with a disability. These include individual rights to health and education that are impacted by the high levels of socio-economic disadvantage [7]. The link between disability and poverty is bi-directional [8]. In the United States and Canada, indigenous populations also experience the negative impact of socio-economic disadvantage on service access [9]–[11]. Racism is another key social determinant of health that negatively impacts service access [12]. Experiences of direct and indirect racism have been linked to distrust of mainstream organizations and providers [2],[13].

Health disparities in childhood disability

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children experience a higher prevalence of disability than other children [4]. They encounter higher rates of hearing loss [14],[15] which has been linked to the high prevalence of middle ear diseases such as otitis media (OM). Rates of OM experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children are among the highest in the world, similar to those in low income countries and at a level classified by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a massive public health problem [2],[16],[17]. OM is also experienced for longer and more persistent periods by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children (32 months compared with 3 months for other children) [18],[19]. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children have also been found to have a significantly higher prevalence of communication disorders [20] and are 1.3 times as likely to require assistance with self-care, mobility or communication than other children [21]. Such disparity is also evident in developmental delay [22],[23]. Early intervention is vital as high rates of disability can negatively impact education, speech, language and social development, and employment outcomes [13],[14],[17],[19],[24]–[26]. It is also acknowledged that intervening at the early stages of childhood development is more cost-effective than intervening later in life [27].

Social determinants of health and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander childhood disability

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children not only experience a higher prevalence of disability but are also disproportionately affected by socio-economic disadvantage [2]. Almost half of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander households are in the lowest income group and are 4 times less likely to be in the highest group than other Australians [2]. Socio-economic disadvantage directly impacts disability for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children [25] who are more likely to experience negative developmental outcomes from disabilities like OM-related hearing loss due to social determinants of health [18]. Addressing the influence of social determinants of health on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander childhood disability requires a shift in thinking as they are often considered indirect to the traditional responsibilities of health, education, and social service sectors [25],[28],[29].

Barriers to service access

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children with a disability and their families face many barriers to service access [25]. A key barrier is the confusion caused by complex and fragmented service provision across government departments and agencies working in professional silos [30],[31]. This lack of integration is often described by a silo approach. A silo refers to systems and processes that operate in isolation from each other.

Policy response to improve service access

The need for holistic and collaborative responses to disability is recognized internationally [8]. The World Report on Disability identifies that policies within health, education and social service sectors all impact on disability outcomes [8]. Nationally, the Australian Government’s “Close the Gap” campaign to reduce Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander disadvantage advocates the need for collaboration across all sectors and levels of Government for effective service coordination [32]. The national policy direction towards collaboration and whole-of-government approaches is reflected in a number of disability-specific policies and strategic frameworks [3],[33]–[36].

Little is known about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children with a disability [4]. Despite the policy push towards collaboration, there has been no systematic attempt to elucidate how collaboration works in practice across and within sectors involved in service provision. Therefore, the current authors set out to answer the question: What are the important components involved in inter- and intra-sector collaboration in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander childhood disability? Understanding these components will be essential in improving service provision and access for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children with a disability and their families.

Methods

We conducted an integrative literature review using a systematic approach to identify components of collaboration guided by an investigator-developed protocol.

Eligibility criteria

Disability is a complex concept with no universally agreed definition [8]. For the purposes of this review, disability refers to long-term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairments that, interacting with environmental and attitudinal barriers, hinder full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others [37].

Included articles focused on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children with a disability and/or their families/carers, or providers of services to this population (eg from the health, education and social service sectors), and include reference to collaboration or interaction within or across two or more providers/sectors. We included articles in the English language specifically addressing Australian issues. No publication date limits were imposed and all study designs were included be they quantitative, qualitative or mixed methods. Commentaries were also included. Articles were included regardless of whether they were published in peer-reviewed journals or grey literature. Articles were excluded if their sole focus was on adolescent or adult disability or a population other than Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Search strategy

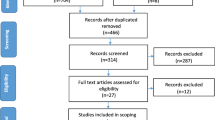

A systematic electronic database search strategy using Boolean terms was developed in collaboration with a health librarian. Search terms were Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms and keywords including derivatives of the key terms ‘collaboration’, ‘child’, ‘disability’ and ‘indigenous’ (see Figure 1 for an example). The grey literature was searched using variations of the key search terms from each of these groupings.

Information sources

A systematic search of health, education, social science, multidisciplinary and indigenous electronic databases was conducted to identify articles published in peer-reviewed journals. The electronic databases Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), EMBASE, PsycInfo, Medline, Education Resources Information Center (ERIC), Social Services Abstracts, Sociological Abstracts, Academic Search Complete, Health Collections (Informit), Indigenous Studies Bibliography (AIATSIS), Australian Public Affairs Information Service (APAIS), Australian Public Affairs Information Service - Health (APAIS-health), Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health (A&TSIhealth), Health & Society, Multicultural Australia and Immigration Studies - Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Subset (MAIS-ATSIS), Rural and Remote Health Database (RURAL), Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet and Google Scholar search engine were searched from 13th – 14th May 2014. Reference lists were also searched for relevant articles.

Grey literature was identified through a search of websites of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and disability representative organizations, the National Disability Organisations’ Clearinghouse, Trove theses database, and Mednar from 23rd May – 4th June 2014. Grey literature identified during the search for articles published in peer-reviewed journals was also reviewed.

Study selection

Returned articles published in peer-reviewed journals were imported into EndNote software. One hundred articles were assessed against eligibility criteria independently by two researchers (AG and MD). Any inconsistencies were discussed until consensus was reached. One researcher (AG) assessed the remaining articles.

Data collection

Data were extracted from the original text of included articles by AG into an a priori designed electronic spreadsheet. Data items included the setting, design, disability/impairment, population, aims, and methods. Data items specific to collaboration were extracted and grouped according to the discipline of providers involved in collaboration, collaborative models, components of collaboration, and key conclusions or recommendations.

Evaluation and analysis

Quality appraisal of the articles published in a peer-reviewed journal was conducted as part of a systematic approach to provide an overview of quality, but was not given weighting in the analysis and synthesis of data due to the lack of formal methods for this in integrative reviews. Quality appraisal of all included articles published in a peer-reviewed journal was conducted independently by two researchers (AG-MD or AG-TL) who met to establish agreement on the final rating. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion. The following critical appraisal tools were used: criteria for assessing qualitative literature [38], the STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklist [39], the Transparent Reporting of Evaluations with Nonrandomized Designs (TREND) checklist [40], the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) [41], and the Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) checklist [42] to assess qualitative, observational, intervention, mixed methods, and review studies, respectively. All included articles were evaluated using the Level of Evidence ranking system by MeInyk and Fineout-Overholt [43]. Data analysis was guided by the narrative synthesis approach by Popay et al. [44]. After developing the preliminary synthesis of findings we searched for a conceptual model. The model needed to provide a holistic framework centered on the child and their family that encompassed the different system levels of collaboration and how they interact with one another. An adaptation [45] of Bronfenbrenner’s ecological model for child development [46] represented a conceptual model in which the relationships in the data could be explored at the macro- (government), exo- (organizational) and meso- (provider) system levels (see Figure 2). The ecological model has previously been referenced in the context of addressing factors influencing equitable service access for underserved populations with a communication disability [47]. To our knowledge, it hasn’t before been applied specifically to service access issues in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander childhood disability. This organizing framework reflects factors that interact to achieve a desired outcome and also the impact of social interaction. Addressing each element discretely without considering the interdependency of elements is unlikely to achieve desirable outcomes.

Factors of inter- and intra-sector collaboration in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander childhood disability. Source: Adapted from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2012 [45].

Results

The database search and peer-reviewed article selection is depicted in Figure 3. Thirteen peer-reviewed articles met inclusion criteria. The majority of studies were qualitative (n = 5) (Table 1) followed by discussion papers (n = 3) (Table 2), observational (n = 2) (Table 3), intervention (n = 1) (Table 4), mixed methods (n = 1) (Table 5) and literature review (n = 1) (Table 6). The grey literature search retrieved 18 articles that met the inclusion criteria (Table 7). In total, 31 articles were included in the review.

The literature predominantly reported on hearing impairment and related disability, such as learning impairments (n = 17). Of the included articles, 14 provided details on 12 different models involving inter- and intra-sector collaboration. The majority of these models centered on collaboration within different areas of the health sector (intra) (n = 5) and between the health and education sectors (inter) (n = 5). Half of the models (n = 6) were set in schools or early childhood centers and the most common model component (n = 6) was a form of capacity building.

Overall, the qualitative studies were generally well-reported according to Kitto et al’s criteria for assessing qualitative literature [38] that evaluated clarification of research, data collection techniques, justification of qualitative approach, and interpretation. None of the studies reported on whether the sampling techniques supported generalizability and seldom demonstrated transparency of data analysis or researcher reflexivity. The mean STROBE score for the observational studies was 16 out of 22 (73%). Both studies reported well on rationale, study design, setting, variables, data sources, outcome data, and generalizability. Neither study reported on the eligibility/selection of participants, study size or study limitations. The TREND score was 15 out of 22 (68%) for the intervention study, which reported well on background, methods, and results but not generalizability. The mixed method study received a MMAT score of 50% for the qualitative component, reporting well on data sources and relationship between findings and context but not on analysis or researcher influence, 75% for the quantitative component, reporting well on sampling strategy, measurements, and response rates, and 50% for the mixed method component, reporting well on research design but not limitations. The literature review received an AMSTAR score of 78% for the 9 applicable items and reported well on study selection, data extraction, search strategy, study characteristics and quality assessment of studies. The literature review did not provide a list of excluded studies and there was no assessment of publication bias.

The following section provides a narrative synthesis of the findings using the macro- (government), exo- (organizational), and meso- (provider) system levels of the ecological model to demonstrate the components of inter- and intra-sector collaboration in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander childhood disability.

Macro- (government) system factors

Factor: Structure of government departments and agencies

The siloed structure of health, education and social service departments and agencies was found to impede service integration and the ability of providers to work collaboratively [48]. Siloes of service provision across government departments and agencies and between levels of government [49] negatively impacts service access for families when they have to navigate different waiting lists and assessment processes, and receive disparate pieces of information from professionals working in isolation [48],[50],[51]. The fragmentation and complexity of government services [52] impede opportunities for collaboration, with some providers reporting difficulties in locating and communicating with relevant services [52],[53]. The adoption of a consultative approach across health, education and social service departments has been recommended as a solution for reducing service duplication and fragmentation and is more aligned with the needs of the child- which are beyond the biomedical and include social, cultural, economic and psychological issues [50].

Factor: Policies

Collaboration at the level of policy making can address the barriers generated by existing structures of government departments and agencies. Formalized agreements like memoranda of understanding (MoU) and collaborative frameworks between government sectors can facilitate collaboration at the level of service provision [54]. MoUs between the health and education sectors have promoted collaboration between health professionals and school staff in screening and treatment of middle ear disease to prevent hearing loss [54],[55]. Frameworks for whole-of-government approaches have been recognized as important in providing coordinated interagency responses [56]–[58]. Formalized agreements should focus on detailing a set of long-, medium- and short-term strategies as it provides clarity around collaborative programs for local providers [55],[59].

Exo- (organizational) system factors

Factor: Communication - Awareness

Although multiple agencies and services may be involved with the care of a child with a disability, this does not mean that they are all aware of each other’s existence, which can lead to duplication of resources [60]. Both families and providers have identified the lack of communication between, and knowledge of, the different agencies and services as a barrier to accessing available support [53]. Raising awareness of collaborative partnerships through the distribution of educational resources across agencies and services facilitates collaboration and the professional development of providers with little knowledge of disability [52],[55],[56]. Distribution of these resources helps providers in remote areas of Australia who have reported feeling like they work in isolation [61]. Advertising collaborative projects and the participating personnel also aids collaboration by reducing the risk associated with providers working outside their professional boundaries [50]. Good community awareness of the organization that is providing a program has also been reported to facilitate the establishment of collaborative organizational partnerships with local services [62].

Factor: Communication – Lack of role clarity and responsibility

Ambiguity and lack of role clarity and responsibilities of different providers, agencies and organizations is a key barrier to collaboration at the exo- (organizational) system level [57]. The role of Aboriginal Health Workers is unclear to some mainstream providers leading to their underutilisation, despite the important role they play [20]. Formally communicating the role and responsibility of each team member is reported as an essential step when putting into practice an inter-agency or multi-disciplinary model [50].

Factor: Financial and human resources

Barriers to the uptake and sustainability of collaborative models include difficulty providing them in sectors that are already facing service provision within a tightening financial environment [48] and a lack of the levels of funding required for providing holistic care approaches [63],[64]. Where organizations continue to provide collaborative models of service provision despite lack of appropriate funding they report that this is done so “on sheer good will”[63] with staff often working beyond their normal hours [64].

Building effective and trusting collaborative relationships across different organizations, agencies and services takes time [57],[62],[65]. Collaboration can be impeded when providers lack the time to develop the skills and build the networks required [53].

Factor: Service delivery setting

The effectiveness of a collaborative program is influenced by the setting in which it is delivered. Collaboration is facilitated by the delivery of mainstream programs in culturally safe environments for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander providers, communities and families [51],[53],[66]. Delivering collaborative health services within schools has been reported to reduce the stigma and the socio-economic impact of having to attend services in mainstream settings for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families, while increasing program participation [66],[67]. Basing health services within schools also allows the services to be responsive to local needs and promotes increased awareness of disability and relevant services among education providers [55],[67]. Collaboration between health and education services based in a single setting provides a one-stop-shop, which facilitates the sharing of information between different services and organizations [52].

Meso- (provider) system factors

A number of key factors of collaboration are found at the front line of collaborative service provision within the meso- (provider) system where the interactions occur between providers, communities and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families and their children.

Factor: Relationships

A key facilitator to collaboration at this level is the coordinator or linking role. The appointment of a person external to the services or agencies involved whose role is to link the different players and act as a trainer, motivator and sustainer can be important to a collaborative inter-disciplinary approach [50],[68],[69]. In the context of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander childhood disability, this person is usually local to the community (eg a community liaison person, Aboriginal Education Worker, Aboriginal Health Worker) and is a conduit between providers, communities and families, also promoting the cultural competence of services [52],[60],[64],[66],[67],[70],[71].

The effectiveness of the coordinator or linking role in facilitating collaboration is influenced by the individual’s characteristics. Being open and inclusive and having personal contacts among decision makers in the organizations, agencies, and services involved promotes collaboration [50]. The effect of individual characteristics on collaborative relationships extends to providers. Collaboration can be impeded by specialist providers choosing to only draw knowledge and skills from their traditional disciplines [48]. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander provider experiences of racism and historical trauma can obstruct engagement with mainstream services [53]. Awareness of cultural difference and individual attitudes [72] and getting along well with people [66] are individual provider characteristics that can facilitate collaborative relationships. Transience and turnover of key staff can disrupt collaborative efforts [50],[56],[68].

Building relationships integral to collaboration at the local level is facilitated by face-to-face provider engagement and ‘linking’ with communities [48],[58],[73]. Provider-to-provider engagement is facilitated by demonstrating mutual respect and understanding [50],[72], having access to direct links for communication, and using open and respectful communication strategies [50],[51]. The importance of engagement is reflected in the collaborative Specialist Integrated Community Engagement (SpICE) model that is based around the concept of ‘linking’ different sectors and the community through engagement to build social capital and a ‘community of learners’ to sustain the collaborative process [48]. Engaging the community can be important to the success of collaborative programs [74] and tapping into existing collaborative relationships in the community can facilitate the engagement process [67]. Where a mainstream organization is unknown to a community, attending interagency meetings in the local area by their providers can facilitate engagement with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander organizations [62].

Factor: Inter- and intra-professional learning

The modeling of inter- and intra-professional collaboration by clinical educators from different disciplines for university students on placement has been reported to facilitate a well-coordinated and holistic approach to learning [72]. The sustainability of collaborative practices is increased by empowering students to incorporate the lessons learned into their future practice [72]. Inter- and intra-professional learning also facilitates collaboration by creating supportive relationships between providers from different disciplines [66].

Discussion

The findings of this review depict a national snapshot of collaboration addressing the limited understanding of how collaboration works in practice in the field of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander childhood disability. The complex nature of childhood development, particularly for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, has seen recognition of the need for a shift from a purely medical view of disability to collaborative approaches that also take into account social and environmental factors [47],[48],[53]. Divisions between mainstream, specialist and non-mainstream services can result from top-down approaches that do not work for addressing complex problems which require ‘buy-in’ to collaborative approaches at all levels [30],[75]. In the move towards collaboration, however, it is important to recognize that collaboration is, in itself, a complex concept which has the potential to inspire innovative solutions or create frustration [76]. Further research is required into collaborations in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander childhood disability to maximize the potential, and minimize any negative impacts, of collaborative approaches. The paucity of research on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children with a disability [4] also means exploring the experiences of children and their families in accessing services is important to completing a holistic picture in order to improve service access.

The importance of respectful communication and culturally appropriate program delivery as found in this review demonstrates the need for cultural competence as a central pillar of collaboration in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander childhood disability. Cultural competence requires promotion of attitudes, knowledge and behavior at individual, institutional and systemic levels in order to deliver effective care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples [77]. Culturally competent organizations and systems need to be reflective of the diverse populations they serve, including at leadership and management levels, and through policies which facilitate cross-cultural communication and access [78]. An increased focus on cultural competence may help to address the negative impact of racism on service access and provision.

Although the review focused on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and is not necessarily generalizable to other indigenous populations, similar health disparities are experienced by indigenous populations worldwide [9],[10],[47],[79]. Investment of time as a facilitator to building sustainable collaborations in the face of government policy and funding cycles is reflected in Canada’s collaborative Aboriginal Head Start program to improve indigenous child development outcomes. A key element to the positive impact of the community-based program is the time it took (more than a decade) to establish credibility within communities and build a trained and experienced workforce to work collaboratively [9]. Long-term commitment to sustainable and collaborative relationships with indigenous organizations and communities is also a strategy identified by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander organizations to achieve genuine partnerships [80].

Building workforce capacity has been recommended as a key element in improving service access for people with a disability and addressing the social determinants of health [8],[47]. Health providers, in particular, have been identified as key players through advocacy, working in partnerships, and working with communities [81]. Collaboration is more likely to be achieved through personal relationships than imposed structures [82], further emphasizing the important role of health, education, and social service providers in improving service access for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander childhood disability through collaboration.

Limitations

The conclusions of systematic reviews are inevitably limited by the breadth and quality of the research available for inclusion. Literature relevant to the topic of interest has been mostly discursive, with only eight empirical studies published in a peer-review journal, only one of which has tested an intervention. The focus of the review on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children with a disability across Australia may mean that it is not generalizable to indigenous populations in other countries or to specific Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations within Australia. This review provides a broad national snapshot of collaboration, but further research within specific local contexts is required to explore ways collaboration can improve access and be responsive to local needs [8],[80]. Due to the focus of the review on inter- and intra-sector collaboration, no data for the microsystem of the family and the individual child were collected. The intra- and inter-personal factors and interactions at this level, however, both influence and are influenced by the factors of collaboration at the meso- (provider), exo- (organizational) and macro- (government) system levels.

Conclusions

The policy shift towards inter-sector collaborative approaches represents a strong opportunity for the health, education, and social service sectors and their providers to work collaboratively with each other in innovative ways. As this review has shown however, collaboration is not a simple concept. Many barriers and facilitators exist at the macro- (government), exo- (organizational) and meso- (provider) system levels that influence the effectiveness of collaborative efforts. By identifying the components of inter- and intra-sector collaborations this review provides information to guide future efforts at developing collaborative solutions to improve service access for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children with a disability and their families.

Abbreviations

- OM:

-

Otitis Media

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- MoU:

-

memoranda of understanding

- MeSH:

-

Medical Subject Headings

- CINAHL:

-

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature

- ERIC:

-

Education Resources Information Center

- APAIS:

-

Australian Public Affairs Information Service

- APAIS-health:

-

Australian Public Affairs Information Service - Health

- A&TSIhealth:

-

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health

- MAIS-ATSIS:

-

Multicultural Australia and Immigration Studies - Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Subset

- STROBE:

-

STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology

- TREND:

-

Transparent Reporting of Evaluations with Nonrandomized Designs

- MMAT:

-

Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool

- AMSTAR:

-

Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews

- SpICE:

-

Specialist Integrated Community Engagement

References

Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council: Cultural Respect Framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health, 2004–2009. 2004, Department of Health South Australia, South Australia

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare: The health and welfare of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people: an overview. 2011, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Canberra

Commonwealth of Australia: 2010–2020 National Disability Strategy: An initiative of the Council of Australian Governments. 2011, Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra

Biddle N, Yap M, Gray M: CAEPR Indigenous Population Project 2011 Census Papers. Paper 6 Disability. 2013, Australian National University, Canberra

Emerson E, Madden R, Graham H, Llewellyn G, Hatton C, Robertson J: The health of disabled people and the social determinants of health. Public Health. 2011, 125: 145-147. 10.1016/j.puhe.2010.11.003.

Grant J, Parry Y, Guerin P: An investigation of culturally competent terminology in healthcare policy finds ambiguity and lack of definition. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2013, 37 (3): 250-256. 10.1111/1753-6405.12067.

Commission AHR: Inquiry into hearing health in Australia: Australian Human Rights Commission submission to the Senate Community Affairs Committee. 2009, Sydney, Australian Human Rights Commission

World Health Organization and World Bank: World Report On Disability. 2011, World Health Organization, Geneva

Ball J: Supporting young indigenous children's language development in Canada: A review of research on needs and promising practices. Can Modern Language Rev. 2009, 66 (1): 19-47. 10.3138/cmlr.66.1.019.

Banks S, Miller D: Empowering indigenous families who have children with disabilities: An innovative outreach model.Disabi Stud Q 2005, 25(2).,

Cappiello M, Gahagan S: Early child development and developmental delay in indigenous communities. Pediatr Clin N Am. 2009, 56 (6): 1501-1517. 10.1016/j.pcl.2009.09.017.

Castleden H: The Silent North: A case study on deafness in a Dene community. Can J Nativ Educ. 2002, 26 (2): 152-168.

Sherwood J: The management of children with otitis media. Aboriginal Islander Health Wor J. 1993, 17 (4): 15-17.

Thorne J: Middle ear problems in Aboriginal school children cause developmental and educational concerns. Contemp Nurse. 2003, 16 (1–2): 145-150.

Australian Bureau of Statistics: National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey 2004–05. 2006, Australian Bureau of Statistics, Canberra

World Health Organization: Chronic Suppurative Otitis Media: Burden Of Illness And Management Options. 2004, World Health Organization, Geneva

Morris P, Leach A, Silberberg P, Mellon G, Wilson C, Hamilton E, Beissbarth J: Otitis media in young Aboriginal children from remote communities in northern and central Australia: A cross-sectional survey.BMC Pediatrics 2005, 5(27).,

Williams C, Jacobs A: The impact of otitis media on cognitive and educational outcomes. Med J Aust. 2009, 191 (9): S69-S72.

Robinson P, Hoskins G, Page S, Peckham C: A national program of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Workers to reduce the incidence of otitis media and hearing loss in children. Aboriginal Isl Health WorkJ. 1997, 21 (5): 27-29.

Aldred R, Forsingdal S, Baker R: Working together to improve the health status and health outcomes for Indigenous children and their families living in urban settings: the speech pathologist's role. ACQuiring Knowl Speech Lang Hear. 2002, 4 (3): 166-169.

Pink B, Allbon P: The Health And Welfare Of Australia's Aboriginal And Torres Strait Islander Peoples 2008. 2008, Australian Bureau of Statistics and the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Canberra

McDonald J, Comino E, Knight J, Webster V: Developmental progress in urban Aboriginal infants: a cohort study. J Paediatr Child Health. 2012, 48 (2): 114-121. 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2011.02067.x.

McDonald J, Webster V, Knight J, Comino E: The Gudaga Study: development in 3-year-old urban Aboriginal children. J Paediatr Child Health. 2014, 50 (2): 100-106. 10.1111/jpc.12476.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare: Stronger Futures in the Northern Territory: Hearing Health Services 2012–2013. 2014, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Canberra

Senate Community Affairs References Committee: Hear Us: Inquiry Into Hearing Health In Australia. 2010, Parliament of Australia Senate, Canberra

Otitis media: helping to close the gap in Indigenous Australia.Medicus (Nedlands, WA) 2013, 53(2):46–47.,

Bowes J, Grace R: Review Of Early Childhood Parenting, Education And Health Intervention Programs For Indigenous Children And Families In Australia. Issues Paper No. 8 Produced For The Closing The Gap Clearinghouse. 2014, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Canberra

Novello A, Degraw C, Kleinman D: Healthy children ready to learn: an essential collaboration between health and education. Public Health Rep. 1992, 107 (1): 3-15.

Baum F: Cracking the nut of health equity: top down and bottom up pressure for action on the social determinants of health. Promot Educ. 2007, 14 (2): 90-95. 10.1177/10253823070140022002.

Hunt J: Engaging with Indigenous Australia—Exploring The Conditions For Effective Relationships With Aboriginal And Torres Strait Islander Communities. Issues paper no. 5. 2013, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare and Australian Institute of Family Studies, Canberra and Melbourne

O'Neill M, Kirov E, Thomson N: A review of the literature on disability services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Austr Indigenous HealthBull. 2004, 4 (4): 1-26.

Council of Australian Governments: National Indigenous Reform Agreement (Closing the Gap). 2008, Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra

Commonwealth of Australia: National Strategic Framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health 2003–2013, Australian Government Implementation Plan 2007–2013. 2007, Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra

Council of Australian Governments: Investing in the early years-a National Early Childhood Development Strategy. 2009, Council of Australian Governments, Canberra

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare: Disability Support Services 2009–10: Report On Services Provided Under The National Disability Agreement. In Disability series. 2011, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Canberra

Scholes J: Deadly Ears Speech Pathology: Working through partnerships to limit the impact of otitis media on the communication development of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children. Talkabout. 2010, 23 (2): 20-21.

Nations U: The United Nations and Disabled Persons-The First Fifty Years. 2006, United Nations, New York

Kitto S, Chesters J, Grbich C: Quality in qualitative research: criteria for authors and assessors in the submission and assessment of qualitative research articles for the Medical Journal of Australia. Med J Aust. 2008, 188: 243-246.

von Elm E, Altman D, Egger M, Pocock S, Gøtzsche P, Vandenbroucke J, STROBE Initiative: The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Bull World Health Organ. 2007, 85 (11): 867-872.

Des Jarlais D, Lyles C, Crepaz N, TREND Group: Improving the reporting quality of nonrandomized evaluations of behavioral and public health interventions: the TREND statement. Am J Public Health. 2004, 94 (3): 361-366. 10.2105/AJPH.94.3.361.

Pluye P, Robert E, Cargo M, Bartlett G, O’Cathain A, Griffiths F, Boardman F, Gagnon MP, Rousseau MC: Proposal: A mixed methods appraisal tool for systematic mixed studies reviews [. Archived by WebCite® athttp://www.webcitation.org/5tTRTc9yJ], [http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com]

Shea B, Grimshaw J, Wells G, Boers M, Andersson N, Hamel C, Porter AC, Tugwell P, Moher D,Bouter LM: Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews.BMC Med Res Method 2007, 7(10).,

Melnyck B, Fineout-Overholt E: Evidence-Based Practice In Healthcare. 2005, Lippincott, Philadelphia

Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, Petticrew M, Arai L, Rodgers M, Britten N, Roen K, Duffy S: Guidance on The Conduct Of Narrative Synthesis In Systematic Reviews. A Product from the ESRC Methods Programme. Version 1. 2006

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare: Social and emotional wellbeing: development of a Children’s Headline Indicator. Cat. no. PHE 158. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2012.

Bronfenbrenner U: The ecology of human development: experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press; 1979.

Westby C: Implementing recommendations of the World Report on Disability for indigenous populations. Int J Speech Language Pathol. 2013, 15 (1): 96-100. 10.3109/17549507.2012.723749.

Clarke K, Denton M: Red Dirt Thinking on child wellbeing in Indigenous, rural and remote Australian communities: The SpICE Model "I just don't want my kid to struggle like I did at school". Austr J Indigenous Educ. 2013, 42 (2): 136-144. 10.1017/jie.2013.21.

Burns J, Thomson N: Review Of Ear Health And Hearing Among Indigenous Australians. 2013, Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet, Western Australia

McSwan D, Ruddell D, Searston I: Report: A Whole Community Approach to Otitis Media-reducing its incidence and effects. 2001, Rural Education, Research and Development Centre, James Cook University, Townsville

DiGiacomo M, Davidson PM, Abbott P, Delaney P, Dharmendra T, McGrath SJ, Delaney J, Vincent F: Childhood disability in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples: A literature review.Int J Equity Health 2013, 12(7).,

Ministerial Advisory Committee: Students with Disabilities: Aboriginal Students with Disabilities. 2003, Government of South Australia, South Australia

DiGiacomo M, Delaney P, Abbott P, Davidson PM, Delaney J, Vincent F: 'Doing the hard yards': carer and provider focus group perspectives of accessing Aboriginal childhood disability services.BMC Health Serv Res 2013, 13(326).,

Western Australian Education and Health Standing Committee: Report on Key Learnings from the Committee Research Trip 11–17 March 2012. 2012, Parliament of Western Australia, Perth

Consultants ARTD: Evaluation of the Aboriginal Otitis Media Screening Program: Final Report. 2008, New South Wales Health, Sydney

Ministerial Advisory Committee: Students with Disabilities: Aboriginal Students with Disabilities: Otitis Media and Conductive Hearing Loss. South Australia: Government of South Australia; 2007.

Health Q: Deadly Ears, Deadly Kids, Deadly Communities: 2009–2013. 2009, Queensland Government, Queensland

Burrow S, Galloway A, Weissofner N: Review Of Educational And Other Approaches To Hearing Loss Among Indigenous People. 2009, Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet, Western Australia

Kirkham L, Wiertsema S, Smith-Vaughan H, Thornton R, Marsh R, Lehmann D, Leach A, Morris P, Richmond P: Are you listening? The inaugural Australian Otitis Media (OMOZ) workshop - towards a better understanding of otitis media. Med J Aust. 2010, 193 (10): 569-571.

Gilroy J: The participation of Aboriginal people with a disability in disability services in New South Wales, Australia.PhD thesis. University of Sydney; 2012.,

Australian Indigenous EarInfoNet and InfoNetwork.Aboriginal and Islander Health Worker Journal 2006, 30(3):20-21.,

Purcal C, Newton BJ, Fisher KR, Eastman C, Mears T: School readiness Program For Aboriginal Children With Additional Needs: Working With Children, Families, Communities And Service Providers. Interim Evaluation Report. 2013, Social Policy Research Centre, University of New South Wales, Sydney

Raman S, Reynolds S, Khan R: Addressing the well-being of Aboriginal children in out-of-home care: Are we there yet?. J Paediatr Child Health. 2011, 47: 806-811. 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2011.02030.x.

Burton J: Opening Doors Through Partnerships: Practical Approaches To Developing Genuine Partnerships That Address Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Community Needs April 2012. 2012, Secretariat of National Aboriginal and Islander Child Care, Victoria

Adams K, Dixon T, Guthrie J: Evaluation of the Gippsland Regional Indigenous Hearing Health Program - January to October 2002. Health Promot J Austr. 2004, 15 (3): 205-210.

Nelson A, Allison H: A visiting occupational therapy service to Indigenous children in school: Results of a pilot project. Austr J Indigenous Educ. 2004, 33: 55-60.

Nelson A, Allison H: Relationships: the key to effective occupational therapy practice with urban Australian Indigenous children. Occup Ther Int. 2007, 14 (1): 57-70. 10.1002/oti.224.

McSwan D, Clinch E, Store R: Otitis media, learning and community. Educ Rural Aust. 2001, 11 (2): 27-32.

Simmons K, Rotumah V, Cookson M, Grigg D: Child Hearing Health Coordinators tackle ear and hearing health in the NT. Chronicle. 2012, 23 (1): 22-23.

Elliott G, Smith AC, Bensink ME, Brown C, Stewart C, Perry C, Scuffham P: The feasibility of a Community-Based Mobile Telehealth Screening Service for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children in Australia. Telemed e-Health. 2010, 16 (9): 950-956. 10.1089/tmj.2010.0045.

Higgins J, Beecher S: The Secretariat of National Aboriginal and Islander Child Care (SNAICC) Early Days Project on Autism Spectrum Disorders August 2010. 2010, Secretariat of National Aboriginal and Islander Child Care, Victoria

Davidson B, Hill AE, Nelson A: Responding to the World Report on Disability in Australia: Lessons from collaboration in an urban Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander school. Int J Speech Lang Pathol. 2013, 15 (1): 69-74. 10.3109/17549507.2012.732116.

New South Wales Ombudsman: Improving Service Delivery To Aboriginal People With A Disability: A Review Of The Implementation of ADHC's Aboriginal Policy Framework and Aboriginal Consultation Strategy. 2010, New South Wales Ombudsman, Sydney

Smith A, Armfield N, Wu W, Brown C, Perry C: A mobile telemedicine-enabled ear screening service for Indigenous children in Queensland: activity and outcomes in the first three years. J Telemed Telecare. 2012, 18: 485-489. 10.1258/jtt.2012.GTH114.

Llewellyn G, Thompson K, Fante M: Inclusion in early childhood services: Ongoing challenges. Austr J Early Child. 2002, 27 (3): 18-23.

Huxham C, Vangen S: Managing To Collaborate: The Theory And Practice Of Collaborative Advantage. 2005, Routledge, United States

National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (NACCHO): Creating the NACCHO Cultural Safety Training Standards and Assessment Process: A background paper. 2011, NACCHO, Canberra

Betancourt J, Green A, Carrillo J, Ananeh-Firempong O: Defining cultural competence: a practical framework for addressing racial/ethnic disparities in health and health care. Public Health Rep. 2003, 118 (4): 293-302. 10.1016/S0033-3549(04)50253-4.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with disability: Wellbeing, participation and support. 2011, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Canberra

Burton J: Coming Together: The Journey Towards Effective Integrated Services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children And Families. 2012, Secretariat of National Aboriginal and Islander Child Care, Victoria

Allen M, Allen J, Hogarth S, Marmot M: Working For Health Equity: The Role Of Health Professionals. 2013, UCL Institute of Health Equity, London

Hunter D, Perkins N, Bambra C, Marks L, Hopkins T, Blackman T: Partnership Working And The Implications For Governance: Issues Affecting Public Health Partnerships. 2010, National Institute for Health Research Service Delivery and Organisation programme, United Kingdom

Acknowledgements

The project team wishes to recognize Linkage project funding support from the Australian Research Council (LP120200484). AG is a PhD student supported by LP120200484. The project team also greatly appreciates the contribution of health librarian, Ms Jane Van Balen.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

MD, PD, PA and JD authored two of the articles included in the current review. Quality appraisal of these articles was conducted by AG and TL to reduce bias, and quality appraisal did not influence the findings of the review. The author(s) declare that they have no other competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

AG contributed to study conceptualization and design, data acquisition and analysis, and drafted the manuscript. MD contributed to study conceptualization and design, inter-rater checks of data acquisition and appraisal, and manuscript revision. TL contributed to study design, inter-rater checks of data acquisition and appraisal, and manuscript revision. PA, PMD and JD contributed to study conceptualization and manuscript revision. PD contributed to study conceptualization, manuscript revision, and cultural mentorship. All authors read and approved the final manuscipt.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Green, A., DiGiacomo, M., Luckett, T. et al. Cross-sector collaborations in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander childhood disability: a systematic integrative review and theory-based synthesis. Int J Equity Health 13, 126 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-014-0126-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-014-0126-y