Abstract

Background

In view of recent evidence from a randomized trial in Burkina Faso that periconceptional iron supplementation substantially increases risk of spontaneous preterm birth (< 37 weeks) in first pregnancies (adjusted relative risk = 2.22; 95% CI 1.39–3.61), explanation is required to understand potential mechanisms, including progesterone mediated responses, linking long-term iron supplementation, malaria and gestational age.

Methods

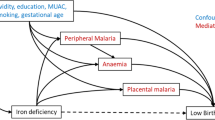

The analysis developed a model based on a dual hit inflammatory mechanism arising from simultaneous malaria and gut infections, supported in part by published trial results. This model is developed to understand mechanisms linking iron supplementation, malaria and gestational age. Background literature substantiates synergistic inflammatory effects of these infections where trial data is unavailable. A path modelling exercise assessed direct and indirect paths influencing preterm birth and gestation length.

Results

A dual hit hypothesis incorporates two main pathways for pro-inflammatory mechanisms, which in this model, interact to increase hepcidin expression. Trial data showed preterm birth was positively associated with C-reactive protein (P = 0.0038) an inflammatory biomarker. The malaria pathway upregulates C-reactive protein and serum hepcidin, thereby reducing iron absorption. The enteric pathway results from unabsorbed gut iron, which induces microbiome changes and pathogenic gut infections, initiating pro-inflammatory events with lipopolysaccharide expression. Data from the trial suggest that raised hepcidin concentration is a mediating catalyst, being inversely associated with shorter gestational age at delivery (P = 0.002) and positively with preterm incidence (P = 0.007). A segmented regression model identified a change-point consisting of two segments before and after a sharp rise in hepcidin concentration. This showed a post change hepcidin elevation in women with increasing C-reactive protein values in late gestation (post-change slope 0.55. 95% CI 0.39–0.92, P < 0.001). Path modelling confirmed seasonal malaria effects on preterm birth, with mediation through C-reactive protein and (non-linear) hepcidin induction.

Conclusions

Following long-term iron supplementation, dual inflammatory pathways that mediate hepcidin expression and culminate in progesterone withdrawal may account for the reduction in gestational age observed in first pregnancies in this area of high malaria exposure. If correct, this model strongly suggests that in such areas, effective infection control is required prior to iron supplementation to avoid increasing preterm births.

Trial registration NCT01210040. Registered with Clinicaltrials.gov on 27th September 2010

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In 2014, estimates for prevalence of PTB in sub-Saharan Africa based on a variety of assessment methods ranged from 8.6 to 16.7% [1]. PTB prevalence and mean gestational age estimates for sub-Saharan African countries dated by ultrasound, which is the most accurate measurement are shown in Table 1. These estimates are compared with those for high income, non-malaria endemic countries. Highest PTB prevalence (27.5%) was observed for women receiving long-term and periconceptional iron in a randomized double blind controlled safety trial of iron supplementation before the first pregnancy in Burkina Faso (PALUFER) [2]. All women in the trial were young primigravidae and in a Malian study, under similar malaria endemic conditions to those in Burkina Faso, comparable gestational age results were observed in first pregnancies. Mean ultrasound dated gestational age was 268.9 days and PTB prevalence 15.8% in Mali [3], very similar to the 269 days and 13.9% prevalence recorded for the control arm in the PALUFER trial (Table 1). In both studies, all women received routine antenatal care, including daily iron prescription in pregnancy. Comparison with other studies listed in Table 1 is limited because none report outcomes separately for primigravidae. There is a need to substantiate the basis for this high PTB prevalence in primigravidae in Burkina Faso and the potential influence of long-term iron supplementation.

Hepcidin is an iron-regulatory hormone produced in the liver that controls the entry of iron into the circulation and tissue iron distribution [4]. Hepcidin exerts its iron-regulatory effects by binding to the transmembrane iron exporter, ferroportin, causing cellular ferroportin internalization and degradation. Thus, increased hepcidin concentration inhibits duodenal iron absorption where ferroportin is needed to deliver absorbed dietary iron to the circulation [4]. Elevated hepcidin thus decreases dietary enteric iron absorption while increasing iron availability to bacterial and fungal pathogens that thrive on gut iron. Iron supplementation would potentially affect iron homeostasis and hepcidin expression if unabsorbed gut iron increased gut inflammation which could stimulate hepcidin production.

In the PALUFER trial malaria prevalence was high above 50% [5], but as most were chronically asymptomatic adolescents, failure to treat these infections probably led to inflammation and gut tissue pathology including detachment of epithelia and shortening of colonic villi as a consequence off epithelial parasite sequestration [6]. The trial documented increased administration of antibiotics for enteric infections as well as antifungal prescriptions for genital infections in supplemented women [7]. As serum iron biomarkers were not improved with supplementation, impaired iron absorption was inferred [5] and serum hepcidin implicated as a key mechanism modulating malarial and gut infections. Preterm birth (PTB) incidence during the rainy season was two and half times higher in the iron arm (P = 0.001) [2], and it was suggested that inflammation related to gut infection and seasonal malaria were initiating this increase. Elevated serum hepcidin and C-reactive protein concentrations were present in malaria parasitaemic, compared to non-parasitaemic, women in the trial [5, 8]. The enteric pathway is developed in the model presented as substantial published information is available to assess its potential influence on host inflammation following long-term iron supplementation. As Plasmodium falciparum parasites sequester in gut epithelium secondary effects on intestinal cell integrity, cell signalling and permeability are considered.

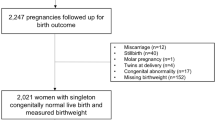

The PALUFER trial has previously been described in detail (see references in “Methods”). Briefly two cohorts of supplemented women were followed: women remaining non-pregnant and those who experienced pregnancy during the 18-month iron supplementation period. Nulliparous participants were individually randomized to receive either a weekly capsule containing ferrous gluconate (60 mg) and folic acid (2.8 mg) (n = 980), or an identical capsule containing folic acid alone (2.8 mg) (n = 979) for 18 months, or until attendance at a first study antenatal visit (ANC1). A total of 478 women became pregnant. Median weekly supplement adherence was 79%. A total of 979 women remained non-pregnant and these were assessed for secondary outcomes after 18 months weekly supplementation. The primary study end-point was malaria parasitaemia prevalence at ANC1; the secondary end-points were prevalence of anaemia and iron deficiency at ANC1, and incidence of low birthweight and PTB. Weekly iron did not significantly reduce iron deficiency, or anaemia prevalence at ANC1. Plasmodium parasitaemia prevalence by microscopy was 54.3%, at ANC1, and prevalence did not differ by trial arm. Free treatment was available for women with fever or other malaria symptoms, but most trial participants were asymptomatic (6.7% with malaria and fever at ANC1). Prevalence of placental malaria parasites at delivery was 33%. In women remaining non-pregnant parasitaemia prevalence was 41% at end assessment after 18 months weekly iron supplementation. Iron-supplemented non-pregnant women also received more antibiotic treatments for non-genital infections (P = 0.014); mainly gastrointestinal infections (P = 0.005), anti-fungal treatments for genital infections (P = 0.014) and analgesics (P = 0.008), than controls.

On the basis of experimental research in animals, Romero et al. in 2014 proposed a two-hit infection hypothesis to account for spontaneous PTB [9, 10], noting the case in humans remained to be established. The PALUFER trial may be an example in humans of enteric iron induced excess preterm incidence due to such a dual hit inflammatory mechanism. In this paper, a model is formulated for malaria and enteric dual infections in order to investigate their synergistic relationship in the presence of long-term periconceptional iron supplementation. To test the hypothesis PALUFER trial data were used to model the dual pathways of malaria and gut infection that predispose to preterm birth and gestation. Data available from the trial can only substantiate part of the model, but data from other studies were used to complete the description of potential pathways for the observed effect of long-term iron supplementation on increased PTB risk. The model tested is that malarial infection induces an elevated hepcidin response that blocks iron absorption, causing gut infections that promote inflammatory pathways leading to PTB. Iron homeostasis is tightly regulated by the membrane iron exporter ferroportin and its regulatory peptide hormone hepcidin. This simple model is in reality more complex, not least because improving iron status (which did not occur in the PALUFER trial) probably also increases the risk of infection as malaria parasites and many bacteria are dependent on iron availability for their growth and virulence [11].

Improved understanding of such interactions may help formulate novel strategies for reducing PTB in malaria endemic regions. This is especially relevant as the World Health Organization currently recommends iron supplementation of 30–60 mg/day iron for 3 consecutive months in a year for non-pregnant females of reproductive age (menstruating adult women and adolescent girls) to better prepare girls for their first pregnancy [12]. Whether this recommended dose is safe or even effective in malaria-endemic settings is not clear.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

Background and published data on the PALUFER trial, its design and results [2, 5, 7, 8, 13,14,15], are summarized in Additional file 1. Laboratory methods are outlined in Additional file 2.

Literature was searched for references illustrative of plausible mechanisms operating for each stage of the model pathways leading to PTB in a malaria endemic area. Search terms focussed on markers of inflammation that could affect birth outcomes. Assumptions for an inflammation-driven model for iron induced excess spontaneous preterm births in the PALUFER trial were formulated derived primarily from published trial results.

Statistical methods

Relationships between PTB and biomarkers were assessed using logistic regression models, plotting fitted probabilities with associated 95% CI. The relationship between maternal serum hepcidin and CRP concentrations was strongly non-linear and was fitted using a segmented linear regression model which fits a continuous line composed of straight-line segments with a change of slope at a fitted change point. More complex models were considered including trial arm as a covariate, but as there were no substantive effects of supplementation, these were not more informative and the univariate analyses are presented. Biomarker levels between PTB and term birth groups were compared using Mann–Whitney U-tests. A path model was constructed based on the formulated schematic which incorporated C-reactive protein (CRP) and hepcidin mediation pathways and PTB. Season was used a proxy for malaria infection. The model was fitted to the PALUFER data as described in Additional file 4.

Results

Assumptions for an inflammation-driven model for iron induced excess spontaneous preterm births in the PALUFER trial

The trial results showed associations between maternal serum CRP concentrations > 5 mg/l at the first (median gestation 18 weeks, IQR 14–23 weeks) and second (median gestation 34 weeks, IQR 33–35 weeks) scheduled antenatal visits (ANC1, n = 282; ANC2, n = 239) and spontaneous PTB incidence (< 37 weeks gestation) [2]. The adjusted relative risk for PTB was higher with CRP > 5 mg/l at ANC1 (1.60, 95% CI 1.00–2.5, P = 0.04) and at ANC2 2.06 (1.04–4.10, P = 0.034). Figure 1 shows the linear association with 95% confidence interval of PTB incidence by log (CRP) for these two visits. There was a strong positive trend with CRP at ANC2 (P = 0.0038), suggesting this inflammatory response was related to spontaneous PTB. Furthermore, the whole gestational age distribution curve was shifted to the left in the iron-supplemented women (see Additional file 3), indicating a population effect on shortening gestation, thereby increasing PTB incidence [2]. Malaria associated inflammation as represented by CRP (geometric mean CRP, mg/l, (n) 1.3 [95% CI 1.0:1.7] (142) without parasitaemia; 9.2 [7.8:10.9] (169) with parasitaemia; relative risk: 1.97 [1.66:2.29], P < 0.001) upregulates hepcidin [8, 16]. At ANC2 (but not ANC1) linear regression showed maternal serum hepcidin concentration was inversely associated with gestational age at delivery (P = 0.002). The linear association and 95% confidence interval of log hepcidin by PTB incidence for these two visits is shown in Fig. 2 with significance only at ANC2 (P = 0.007). Mean ± SD serum hepcidin concentration was higher at both ANC1 and ANC2 in preterm compared to term deliveries (ANC1, 6.9 ± 13.5 vs 5.7 ± 6.9 nmol/l, P = 0.74; ANC2, 4.8 ± 5.3 vs 3.2 ± 6.3 nmol/l, P = 0.004).

Association between maternal serum C-reactive protein concentration and spontaneous preterm birth in the PALUFER study. Fit and P-values derived from a logistic regression of preterm birth incidence (proportion) against log(CRP mg/l). Stippled lines are 95% confidence interval. Rugs at top and bottom indicate where preterm birth (red) and non-preterm birth (green) deliveries lie. ANC1 and ANC2 are the scheduled study antenatal visits. The regression slopes are 0.11 (95% CI − 0.06:0.29) for ANC1 and 0.39 (0.11:0.67) for ANC2 per unit log(CRP)

Association between maternal serum hepcidin concentration and spontaneous preterm birth in the PALUFER study. Fit and P-values derived from a logistic regression of preterm birth incidence (proportion) against log(hepcidin nmol/ml). Stippled lines are 95% confidence interval. Rugs at top and bottom indicate where preterm birth (red) and non-preterm birth (green) deliveries lie. ANC1 and ANC2 are the scheduled study antenatal visits. The regression slopes are 0.01 (95% CI − 0.20:0.22) for ANC1 and 0.38 (0.10:0.66) for ANC2 per unit log(hepcidin)

In normal pregnancy hepcidin expression decreases physiologically in the second and third trimesters, thereby increasing the supply of iron to the circulation [17]. As malaria risk also alters with gestational age, especially in primigravidae, gestational change in hepcidin may be inhibited by concurrent malaria inflammation. Figure 3 shows plots of the relationship between maternal serum hepcidin and CRP concentrations at the three trial assessment time-points: end assessment for women remaining non-pregnant; for pregnant women at ANC1 and at ANC2. The figure shows a segmented regression model consisting of two segments before and after a sharp rise (post-change) in hepcidin concentration. In the PALUFER trial there was a post-change hepcidin elevation at ANC2 (post-change slope 0.55; 95% CI 0.39–0.92; P < 0.001).

Association of maternal serum hepcidin and C-reactive protein concentration at the three assessment time-points in the PALUFER study. The lines show a segmented regression model consisting of linear segments before and after a (fitted) change point, and the different regression slopes before and after this change point with associated 95% CI are shown below the plots. The 95% confidence interval is shown for the change point estimate as a horizontal error bar and numerically below the plot. The vertical stippled lines show the cut points for CRP at 5 mg/l and 10 mg/l. Open and closed symbols indicate iron intervention (closed) and control (open) arms. Serum hepcidin is in nmol/l

Iron induced enteric inflammation before and during pregnancy

Pathological changes (including detachment of epithelia and shortening of colonic villi) occur in the permeability, leakage of infected erythrocytes into the lumen and dysbiosis of the intestinal gut during P. falciparum infection. Such changes may cause increased intestinal microbiota [6]. The extra enteric iron available with long-term supplementation potentially contributes to disease severity in the gut with a shift in microbiota composition [18, 19] and multiplication of fungal [20] and bacterial [21] pathogens that produce intestinal epithelium biofilm and also contaminate the genital tract. Expression of regulatory inflammatory genes can cause intestinal inflammation, disrupt the intestinal barrier function [22, 23] and prime inflammasome activation. The latter is a multiprotein oligomer responsible for the activation and assembly of the Nod-Like Receptor (NLR)P3 leading to release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-β [24]. Malaria infection decreases absorption of fortification iron in women [25], which can induce an inflammatory gut reaction [26, 27]. In this way, Plasmodium parasites can have an impact on composition of gut microbiota although bi-directional mechanisms are not well understood, especially in pregnancy [6]. Reactive nitric oxide (NO) intermediates play a prominent role in intestinal barrier damage by inducing enterocyte apoptosis and inhibiting the epithelial restitution processes [28, 29]. NO generation, produced by inducible NO synthase (iNOS), occurs with asymptomatic malaria. Some of the changes related to inflammation from gut infection and which activate pro-inflammatory factors are outlined in Fig. 4. This shows a positive feedback loop with hepcidin expression resulting from gut infection limiting dietary iron absorption, with enteric iron enhancing gut inflammation. Long-term iron supplementation would be expected to exacerbate this cycle as this in addition to food iron increases enteric iron concentration, especially in iron replete women whose iron absorption is already inhibited.

Synergistic effects of dual exposure with chronic malaria and enteric infection in iron supplemented adolescents and increased risk of preterm birth. Red arrows: malaria loop; blue arrows: enteric loop; black arrows: iron pathway; brown arrows: preterm pathway. Numbers in square brackets refer to manuscript references with evidence for the specific pathway events. Box texts refer to pathophysiological consequences and stages in the specific pathways. Body iron stores refers to the observation that in the PALUFER trial mean body iron stores were higher in pregnant women with malaria [14], indicating that better iron status was associated with increased malaria infection risk. Nulliparous participants were individually randomized to receive either a weekly capsule containing ferrous gluconate (60 mg elemental iron, 479 mg gluconate) and folic acid (2.8 mg), or an identical capsule containing folic acid alone (2.8 mg). CRP: C-reactive protein; NO: nitric oxide; LPS: lipopolysaccharide; pro-inflammatory cytokines are interleukin (IL)-1 beta (β); IL-6; IL-8; interferon (IFN) gamma (ɣ); Nod-Like Receptor (NLR)P3: gene belonging to the NLRP3 inflammasome complex

Figure 4 highlights the importance of release of endotoxins and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) into the circulation with inflammation [30, 31]. LPS is a central component of the outer membrane in Gram-negative bacteria and frequently plays a key role during host–pathogen interaction and the establishment of chronic infection in the gut, genital tract and other mucosa. LPS-mediated virulence resides in its endotoxic activity [32]. LPS induces release of acute phase blood proteins associated with pro-inflammatory signalling pathways. Studies in experimental animals have shown intestinal bacteria, especially Enterobacteriaceae and Clostridium perfringens, may influence the level of lipopolysaccharide binding protein and CRP in blood plasma [33] Strong activation is reported in macrophages in response to LPS of NF-κB, a highly conserved transcription factor that regulates inflammatory responses, cellular growth and apoptosis [34]. Placental mediated responses to LPS have been reported in experimental animals with greater cytokine responses in preterm placentas and increased phosphorylated NF-κB induction which may occur by activation of the Toll-like receptor (TLR) pathway [35]. TLRs are essential for an effective host cell response to LPS. Circulating LPS binding to membrane-bound TLR4 results in a series of kinase cascades that phosphorylate NFκB into the nucleus where it acts as a transcription factor stimulating production of proinflammatory cytokines. Placental TLRs can result from transient clinically inapparent maternal bacteraemia [36].

Hepcidin expression is reported to negatively affect proliferation of intrahepatic sporozoites [37], but conversely it may increase susceptibility to iron dependent gut pathogens, e.g., Salmonella. This is because iron-loaded macrophages, which increase with hepcidin expression, have an impaired potential to kill various pathogens. This is partly attributed to reduced formation of NO which is essential to fight infection, as iron blocks transcription of inducible NO synthase (iNOS) [38]. Regulatory mechanisms would depend on the intracellular or extracellular location of bacteria.

Placental malaria and malaria-induced gut inflammation

Concurrent effects of pregnancy malaria are shown in Fig. 4. The primary events are sequestration of P. falciparum in the placenta and parasite adherence to gut endothelial cells with altered intestinal barrier function [6, 39]. Adherence of infected erythrocytes containing late developmental stages of the parasite (trophozoites and schizonts) to the endothelium of capillaries and venules, is characteristic of P. falciparum infections. Malaria in pregnancy is characterized by the accumulation of infected red blood cells, leukocyte infiltration, and excessive fibrin deposition in the intervillous space of the placenta [40], and is associated with increased risk of low birthweight, attributed to PTB and fetal growth restriction with early development of clinical malaria in infants [41]. Placental intervillositis occurs [36], with induction of oxidative stress biomarkers [42]. Oxidative stress, is an imbalance between oxidants and antioxidants in favour of oxidants, and leads to disruption of redox signalling and physiological function [43]. Placental parasites result in haemozoin formation leading to stimulation of cytokine responses [44, 45], regulation of iNOS expression [46] and NLRP3 inflammasome priming [47]. Haemozoin is an iron-containing pigment which accumulates as cytoplasmic granules in malaria parasites and is a breakdown product of hemoglobin.

The induction of inflammatory cytokines can modulate pregnancy outcomes with beneficial and/or detrimental effects [48]. Maintenance of an appropriate ratio of pro-and anti-inflammatory responses at the feto-maternal interface is a hallmark of successful pregnancy A systemic inflammatory response to malaria during pregnancy leads to increased interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-22, interferon (INF)-Ɣ and soluble tumour necrosis factor (sTNF)-RII in maternal blood [3, 41, 45,46,47,48,49,50,51]. Placental IL-6 and IL-8 have been associated with pregnancy loss and PTB [3, 47,48,49]. These biomarkers are predominantly pro-inflammatory, but some have variable anti-inflammatory effects. Expression of CRP, the synthesis of which is rapidly upregulated with inflammation, occurs principally in hepatocytes, under the control of cytokines originating at the site of pathology [52]. The pro-inflammatory cell signalling upregulates hepcidin [53], with increased iron accumulation in macrophages [16, 37], and reduces iron absorption.

The inflammasome promotes maturation and secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL- 18, which results in pro-inflammatory cell death [54]. Nod-Like Receptor (NLR) P3/P12 dependent activation of caspase-1 is likely to be a key event in mediating systemic production of IL-1β with hypersensitivity to secondary bacterial infection during malaria [55]. Bacterial super-infection is well described in acute malaria, and low-density asymptomatic malaria infections are a risk factor for non-typhi salmonella bacteraemia in children [56] and young adults in Burkina Faso [57]. Salmonella typhimurium during malaria may facilitate bacterial colonization [58], and experimental studies in animals indicate shifts in enteric microbiota and increase in susceptibility to intestinal colonization by S. typhimurium [59]. In vivo evidence indicates that S. typhimurium benefits from iron availability during malaria infection [60]. Higher mean body iron stores, as observed in malaria-positive primigravidae in the PALUFER trial [8], and also reported in a Congolese study [61], may favour colonization with S. typhimurium. Evidence is required to substantiate this association in young adults and pregnant women.

Inflammatory stimuli leading to preterm birth

A maternal cortisol response occurs with inflammation. In non-endemic malaria areas a majority of studies have reported a consistently negative association between maternal cortisol and infant birthweight [62,63,64]. In contrast studies in malaria endemic areas have reported significant positive associations between cortisol concentration and P. falciparum infection prevalence [65, 66]. The process of parturition is associated with inflammation within uterine tissues and it is generally accepted that inflammatory stimuli from multiple extrinsic and intrinsic sources induce labor [67], associated with increases in IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-8 gene expression [68]. Inflammatory stimuli induce labour by affecting progesterone transcriptional activity in uterine cells and causing functional progesterone withdrawal [69]. Progesterone plays a critical role in successful pregnancy and low progesterone concentration is reported in preterm delivery [69], with functional involvement of hormonal and inflammatory stimuli [70, 71], or in experimental animals 24 h following LPS exposure [72]. Hepcidin synthesis in experimental animals has been linked to progesterone receptor membrane component-1 [73]. Young maternal age is important because acquisition of progesterone responsiveness depends on endometrial maturation. Persistence of partial progesterone resistance in adolescents could compromise deep placentation increasing risk of PTB [74].

The characteristics of pregnancy malaria and enteric infection outlined in Fig. 4 indicate a state of chronic inflammation, a maternal cortisol response, progesterone withdrawal and increased risk of PTB. The pathways involved include inflammation-induced cytotoxic effects on progesterone production [75, 76], with progesterone modulation of LPS-induced responses [77, 78]. Metabolic endotoxaemia would impair progesterone production and increase progesterone receptor sensitivity [76, 79, 80]. Concurrent infections including lower genital infections and chorioamnionitis would be expected to be contributory by enhancing activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome, especially with intra-amniotic infection [81]. While the path model is not limited to iron supplemented women, supplementation would influence enteric inflammation before and during pregnancy.

Path modelling of dual infection, preterm birth and gestation

A path model was constructed based on the schematic in Fig. 4 which incorporated the CRP and hepcidin mediation pathway. Full details are provided in Additional file 4. Figure 5 shows the fitted model along with the estimated coefficients. This model confirmed the seasonal malaria effects on PTB, with mediation through CRP and (non-linear) hepcidin induction. As there was no data on the enteric mediators, this process manifests itself as a strong direct treatment effect on PTB. As in previous analyses, any direct induction of hepcidin from iron supplementation is negligible. An additional effect was detected of season on PTB (broken line in Fig. 5). This may reflect a residual effect due to incomplete measurement of the mediating variables (a single measurement at one time may not capture the full extent of the mediation). Alternatively, it may capture other seasonal effects that are not related to malaria, possibly associated with other infections or nutritional changes.

Path model for evaluation of inflammatory factors influencing preterm birth and gestation. See Additional file 3. A fitted path model. Fitted coefficients are shown along the paths and represent effect sizes [differences in log(hepcidin), log(CRP), or gestation, or odds ratios for PTB per unit log(CRP), log(hepcidin)], treatment/non-treatment or amplitude of seasonal variability with 95% CI. The CRP–hepcidin relationship is non-linear and is illustrated graphically (see also Additional file 4: Figure S2). The model fits both PTB and gestation (in days), so there are coefficients for both relationships indicated by blue and green text respective

There was no statistically convincing evidence for any other mechanistic paths beyond the model presented.

Discussion

The conditions for this PTB model presuppose a setting in which inflammation is due to a common exposure which is experienced by most women, such that the gestational age distribution is shifted to the left with the resultant gestational effect unlikely to be specific to a sub-phenotype [2]. In other words, the inflammatory impact affects most of the population at risk rather than subgroups with selected risk factors. This occurred for women in the PALUFER trial and seems likely to be the case in comparable malaria transmission areas of sub-Saharan Africa where P. falciparum prevalence is high, especially in adolescents and primigravidae [82]. A population shift to shorter gestational age has similarly been reported for malaria-exposed primigravidae and secundigravidae in a Tanzanian study [83]. In such settings, the majority of women experience low density, asymptomatic chronic malarial infections that are frequently sub-microscopic and hence remain untreated [84]. With high infection exposure and chronic infections, many primigravidae would experience a sustained inflammatory response spanning the periconceptional period. This is prior to the development of parity-specific malaria immunity which initially develops following malaria infection during the first pregnancy [85].

The inflammatory stimulus defined by CRP was associated with higher hepcidin concentrations with increasing CRP levels in both non-pregnant women and in primigravidae at ANC1. Hepcidin elevation occurred at lower CRP levels (< 5 mg/l) later in gestation at ANC2 (Fig. 3), which was almost sufficient to cancel out the expected late pregnancy physiological suppression of hepcidin [17]. Hepcidin elevation later in gestation is consistent with chronic malaria in pregnancy. Some caution is necessary as numbers are smaller and scattered in post change-point groups, but the analysis is consistent with the hypothesis of hepcidin elevation late in pregnancy in response to malaria and iron-induced gut inflammation. In areas with lower malaria endemicity the inflammatory stimulus would be less, leading to lower hepcidin expression, enhanced gut iron absorption, and less enteric inflammation with reduced risk of PTB. Genital inflammation could additively contribute to hepcidin expression as vaginal lactoferrin, an immune response protein to mucosal infection, was positively associated with serum hepcidin (P = 0.047) in a sub-study using vaginal eluates from these women [15]. If there is a supposition of an inflammatory threshold, this would lead to the timing of human parturition being determined by the trajectory of the inflammatory load increase, and the level of the inflammatory load threshold needed for progesterone signalling [67].

Body iron concentration was higher in women with malaria in this cohort of women [8]. Women with better iron status are more iron replete which would upregulate hepcidin binding to ferroportin, blocking uptake of dietary iron from the intestine. Malaria and gut inflammation in the model also upregulate hepcidin. This has the potential in iron replete women for enhancement of the hepcidin feedback loop leading to an additive or cumulative inflammatory response and increasing risk of PTB. Iron deficient women, who may experience less malaria with correspondingly fewer enteric infections (and possibly fewer genital infections arising from gut contamination) would be at lower risk of entering this cycle with potentially better birth outcomes than iron replete women. In a longitudinal study in Papua New Guinea iron deficiency was associated with substantially reduced odds of low birthweight [86]. The investigators considered the effect was predominantly through malaria independent protective mechanisms, with the association between iron deficiency and PTB restricted to primigravidae, although gestational age was not assessed by ultrasound.

A limitation of this analysis is the scarcity of data for comparative analysis and lack of data on enteric biomarkers or helminthic infections from the PALUFER trial, although all participants received single doses of albendazole and praziquantel at enrolment. Data on serum or red cell folate was not available to assess whether folate status was an additional factor in the model. For example, all women had received 2.8 mg weekly folic acid, a dose which may provide sufficient substrates to enhance folate metabolism in P. falciparum infection [87], thereby increasing parasite load and systemic inflammation. Thus, whilst this paper presented and tested a putative causal model, this is not complete and the omission of other pathways and measurement error mean that the results, although suggestive, need to be treated with some caution.

Other field trials assessing periconceptional nutrient interventions have mostly been undertaken in non-malaria endemic areas [14], and effect estimates have prioritized nutritional rather than inflammatory biomarker outcomes. Infection exposures have been poorly defined. In addition, the question arises whether common non-infectious exposures might provide an additional inflammatory stimulus for induction of a hepcidin response sufficient to influence dietary iron absorption. A possible example of this would be prenatal exposure to high levels of ambient air pollution, which has been frequently associated with PTB in non-malaria-endemic areas [88].

Policy and research implications

Interventions to prevent PTB focus mainly on managing risk factors [89]. Improving the biologic understanding of nutritional and inflammatory mediators, and their seasonal patterns in malaria endemic areas may provide novel ways to identify interventions to reduce inflammatory stimuli. A more clinical perspective requires a focus on female adolescents who face high risk of malaria exposure in their first pregnancy, and in whom inflammation exposure may remain unrecognized due to chronic asymptomatic malaria infection in areas with high malaria transmission. The use of long-term iron supplementation, as recommended by WHO, may be detrimental—even when available on an intermittent seasonal basis, as synergistic enteric inflammatory responses would preclude safety. The occurrence of combined exposures with malaria, enteric, as well as genital infections provides an opportunity to consider other co-infection models [90] and double-hit mechanisms [10], which would necessitate different options for infection control. The role for anti-inflammatory agents, which have been evaluated only for therapeutic use, such as targeting the NLRP3 axis might be considered [91]. However, when malaria and enteric infection co-exist, and if the latter are enhanced by iron supplementation, then this model strongly suggests that malaria control in areas with comparable infection exposures should take precedence to iron supplementation to avoid increasing PTB risk.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request and will be made available following an end user data agreement and sponsor approval.

Abbreviations

- PTB:

-

preterm birth

- LPS:

-

lipopolysaccharide

- NO:

-

nitric oxide

- iNOS:

-

inducible nitric oxide synthase

- IL-1β:

-

interleukin 1 beta

- IL-6:

-

interleukin 6

- IL-8:

-

interleukin 8

- IL-10:

-

interleukin 10

- IL-18:

-

interleukin 18

- IL-22:

-

interleukin 22

- INF-Ɣ:

-

interferon gamma

- sTNF-RII:

-

soluble Tumour Necrosis Factor Receptor II

- TLR:

-

Toll-like receptor

- NF-kB:

-

nuclear factor kappa light chain enhancer of activated B cells

- NLRP3:

-

Nod-Like Receptor gene coding proteins belonging to the NLRP3 inflammasome complex

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- ANC1:

-

first study antenatal visit

- ANC2:

-

second study antenatal visit

References

Chawanpaiboon S, Vogel JP, Moller AB, Lumbiganon P, Petzold M, Hogan D, et al. Global, regional, and national estimates of levels of preterm birth in 2014: a systematic review and modelling analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;1:e37–46.

Brabin B, Gies S, Roberts SA, Diallo S, Lompo OM, Kazienga A, et al. Excess risk of preterm birth with periconceptional iron supplementation in a malaria endemic area: analysis of secondary data on birth outcomes in a double blind randomized controlled safety trial in Burkina Faso. Malar J. 2019;18:161.

Fried M, Kurtis JD, Swihart B, Pond-Tor S, Barry A, Sidibe Y, et al. Systemic inflammatory response to malaria during pregnancy is associated with pregnancy loss and preterm delivery. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65:1729–35.

Ganz T, Nemeth E. Hepcidin and iron homeostasis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1823:1434–43.

Gies S, Diallo S, Roberts SA, Kazienga A, Powney M, Brabin L, et al. Effects of weekly iron and folic acid supplements on malaria risk in nulliparous women in Burkina Faso: a periconceptional double-blind randomized controlled non-inferiority trial. J Infect Dis. 2018;218:1099–109.

Coban C, Lee MSJ, Ishii KJ. Tissue-specific immunopathology during malaria infection. Nat Rev Immunol. 2018;18:266–78.

Brabin L, Roberts SA, Gies S, Nelson A, Diallo S, Stewart CJ, et al. Effects of long-term weekly iron and folic acid supplementation on lower genital tract infection—a double blind, randomised controlled trial in Burkina Faso. BMC Med. 2017;15:206.

Diallo S, Roberts SA, Gies S, Rouamba T, Swinkels DW, Geurts-Moespot AJ, et al. Malaria early in the first pregnancy: potential impact of iron status. Clin Nutr. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2019.01.016 (Epub ahead of print).

Romero R, Miranda J, Chaiworapongsa T, Korzeniewski SJ, Chaemsaithong P, Gotsch F, et al. Prevalence and clinical significance of sterile intra-amniotic inflammation in patients with preterm labor and intact membranes. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2014;72:458–74.

Cardenas I, Mor G, Aldo P, Lang SM, Stabach P, Sharp A, et al. Placental viral infection sensitizes to endotoxin-induced pre-term labor: a double hit hypothesis. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2011;65:110–7.

Brabin L, Brabin BJ, Gies S. Influence of iron status on risk of maternal or neonatal infection and on neonatal mortality with an emphasis on developing countries. Nutr Rev. 2013;71:528–40.

WHO. Guidelines: daily iron supplementation in adult women and adolescent girls. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016.

Rouamba T, Nakanabo-Diallo S, Derra K, Rouamba E, Kazienga A, Inoue Y, et al. Socioeconomic and environmental factors associated with malaria hotspots in the Nanoro demographic surveillance area, Burkina Faso. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:249.

Brabin BJ, Gies S, Owens S, Claeys Y, D’Alessandro U, Tinto H, et al. Perspectives on the design and methodology of periconceptional nutrient supplementation trials. Trials. 2016;17:58.

Roberts SA, Brabin L, Diallo S, Gies S, Nelson A, Stewart C, et al. Mucosal lactoferrin response to genital tract infections is associated with iron and nutritional biomarkers in young Burkinabé women. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2019;73:1464–72.

Spottiswoode N, Duffy PE, Drakesmith H. Iron, anemia and hepcidin in malaria. Front Pharmacol. 2014;5:125.

Fisher AL, Nemeth E. Iron homeostasis during pregnancy. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;106(Suppl 6):1567S–74S.

Clemente JC, Manasson J, Scher JU. The role of the gut microbiome in systemic inflammatory disease. BMJ. 2018;360:j5145.

Ahmed I, Roy BC, Khan SA, et al. Microbiome, metabolome and inflammatory bowel disease. Microorganisms. 2016. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms4020020.

Paterson MJ, Oh S, Underhill DM. Host-microbe interactions: commensal fungi in the gut. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2017;40:131–7.

Cherayil BJ, Ellenbogen S, Shanmugam NN. Iron and intestinal immunity. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2011;27:523–8.

Odenwald MA, Turner JR. The intestinal epithelial barrier: a therapeutic target? Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14:9–21.

Hoytema van Konijnenburg DP, Reis BS, Pedicord VA, Farache J, Victora GD, Mucida D. Intestinal epithelial and intraepithelial T cell crosstalk mediates a dynamic response to infection. Cell. 2017;171:783–94.

Swanson KV, Deng M, Ting JP. The NLRP3 inflammasome: molecular activation and regulation to therapeutics. Nat Rev Immunol. 2019;19:477–89.

Cercamondi CI, Egli IM, Ahouandjinou E, Dossa R, Zeder C, Salami L, et al. Afebrile Plasmodium falciparum parasitemia decreases absorption of fortification iron but does not affect systemic iron utilization: a double stable-isotope study in young Beninese women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92:1385–92.

Verma S, Cherayil BJ. Iron and inflammation—the gut reaction. Metallomics. 2017;9:101–11.

Fang S, Zhuo Z, Yu X, Wang H, Feng J. Oral administration of liquid iron preparation containing excess iron induces intestine and liver injury, impairs intestinal barrier function and alters the gut microbiota in rats. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2018;47:12–20.

Grishin A, Bowling J, Bell B, Wang J, Ford HR. Roles of nitric oxide and intestinal microbiota in the pathogenesis of necrotizing enterocolitis. J Pediatr Surg. 2016;51:13–7.

Chadha S, Jain V, Gupta I, Khullar M. Nitric oxide metabolite levels in preterm labor. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2007;33:710–7.

Madan N, Kaysen GA. Gut endothelial leakage of endotoxin may be the source of vascular inflammation and injury in CKD. How can this be targeted? J Ren Nutr. 2018;28:1–3.

Citronberg JS, Curtis KR, White E, Newcomb PA, Newton K, Atkinson C, et al. Association of gut microbial communities with plasma lipopolysaccharide-binding protein (LBP) in premenopausal women. ISME J. 2018;12:1631–41.

Maldonado RF, Sá-Correia I, Valvano MA. Lipopolysaccharide modification in Gram-negative bacteria during chronic infection. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2016;40:480–93.

Schroedl W, Kleessen B, Jaekel L, Shehata AA, Krueger M. Influence of the gut microbiota on blood acute-phase proteins. Scand J Immunol. 2014;79:299–304.

Lawrence T. The nuclear factor NF-kappaB pathway in inflammation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2009;1:a001651.

Boles JL, Ross MG, Beloosesky R, Desai M, Belkacemi L. Placental-mediated increased cytokine response to lipopolysaccharides: a potential mechanism for enhanced inflammation susceptibility of the preterm fetus. J Inflamm Res. 2012;5:67–75.

Hussein K, Stucki-Koch A, Kreipe H, Feist H. Expression of Toll-Like receptors in chronic histiocytic intervillositis of the placenta. Fetal Pediatr Pathol. 2015;34:407–12.

Portugal S, Carret C, Recker M, Armitage AE, Gonçalves LA, Epiphanio S, et al. Host-mediated regulation of superinfection in malaria. Nat Med. 2011;17:732–7.

Weiss G. Impact of metals on immune response and tolerance, and modulation of metal metabolism during infection. In: Nriagu JO, Skaar EP, editors. Trace metals and infectious diseases. Cambridge: The MIT Press; 2015. p. 152–6.

Church JA, Nyamako L, Olupot-Olupot P, Maitland K, Urban BC. Increased adhesion of Plasmodium falciparum infected erythrocytes to ICAM-1 in children with acute intestinal injury. Malar J. 2016;15:54.

Brabin BJ, Ramagosa C, Abdelgalil S, Menendez C, Veroeff F, McGready R, et al. The sick placenta-the role of malaria. Placenta. 2004;25:359–78.

Moya-Alvarez V, Abellana R, Cot M. Pregnancy-associated malaria and malaria in infants: an old problem with present consequences. Malar J. 2014;13:271.

Megnekou R, Djontu JC, Bigoga JD, Medou FM, Tenou S, Lissom A. Impact of placental Plasmodium falciparum malaria on the profile of some oxidative stress biomarkers in women living in Yaoundé, Cameroon. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0134633.

Sarr D, Cooper CA, Bracken TC, Martinez-Uribe O, Nagy T, Moore JM. Oxidative stress: a potential therapeutic target in placental malaria. Immunohorizons. 2017;1:29–41.

Moore JM, Chaisavaneeyakorn S, Perkins DJ, Othoro C, Otieno J, Nahlen BL, et al. Hemozoin differentially regulates proinflammatory cytokine production in human immunodeficiency virus-seropositive and -seronegative women with placental malaria. Infect Immun. 2004;72:7022–9.

Singh KP, Shakeel S, Naskar N, Bharti A, Kaul A, Anwar S, et al. Role of IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α cytokines and TNF-α promoter variability in Plasmodium vivax infection during pregnancy in endemic population of Jharkhand, India. Mol Immunol. 2018;97:82–93.

Ranjan R, Karpurapu M, Rani A, Chishti AH, Christman JW. Hemozoin regulates iNOS expression by modulating the transcription factor NF-κB in macrophages. Biochem Mol Biol J. 2016. https://doi.org/10.21767/2471-8084.100019.

Kalantari P, DeOliveira RB, Chan J, Corbett Y, Rathinam V, Stutz A, et al. Dual engagement of the NLRP3 and AIM2 inflammasomes by plasmodium-derived hemozoin and DNA during malaria. Cell Rep. 2014;6:196–210.

Conroy AL, Liles WC, Molyneux ME, Rogerson SJ, Kain KC. Performance characteristics of combinations of host biomarkers to identify women with occult placental malaria: a case-control study from Malawi. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e28540.

Requena P, Barrios D, Robinson LJ, Samol P, Umbers AJ, Wangnapi R, et al. Proinflammatory responses and higher IL-10 production by T cells correlate with protection against malaria during pregnancy and delivery outcomes. J Immunol. 2015;194:3275–85.

Abrams ET, Milner DA Jr, Kwiek J, Mwapasa V, Kamwendo DD, Zeng D, et al. Risk factors and mechanisms of preterm delivery in Malawi. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2004;52:174–83.

Ruizendaal E, Schallig HDFH, Bradley J, Traore-Coulibaly M, Lompo P, d’Alessandro U, et al. Interleukin-10 and soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor II are potential biomarkers of Plasmodium falciparum infections in pregnant women: a case-control study from Nanoro, Burkina Faso. Biomark Res. 2017;5:34.

Pepys Mark B, HirschfieldJ Gideon M. C-reactive protein: a critical update. Clin Invest. 2003;111:1805–12.

Kanamori Y, Murakami M, Sugiyama M, Hashimoto O, Matsui T, Funaba M. Hepcidin and IL-1β. Vitam Horm. 2019;110:143–56.

Man SM, Karki R, Kanneganti TD. Molecular mechanisms and functions of pyroptosis, inflammatory caspases and inflammasomes in infectious diseases. Immunol Rev. 2017;277:61–75.

Ataide MA, Andrade WA, Zamboni DS, Wang D, Souza Mdo C, Franklin BS, Elian S, et al. Malaria-induced NLRP12/NLRP3-dependent caspase-1 activation mediates inflammation and hypersensitivity to bacterial superinfection. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1003885.

Biggs HM, Lester R, Nadjm B, et al. Invasive Salmonella infections in areas of high and low malaria transmission intensity in Tanzania. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58:638–47.

Park SE, Pak GD, Aaby P, Adu-Sarkodie Y, Ali M, Aseffa A, et al. The relationship between invasive nontyphoidal Salmonella disease, other bacterial bloodstream infections, and malaria in Sub-Saharan Africa. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;15(62 Suppl 1):S23–31.

Mooney JP, Galloway LJ, Riley EM. Malaria, anemia, and invasive bacterial disease: a neutrophil problem? J Leukoc Biol. 2019;105:645–55.

Mooney JP, Lokken KL, Byndloss MX, George MD, Velazquez EM, Faber F, et al. Inflammation-associated alterations to the intestinal microbiota reduce colonization resistance against non-typhoidal Salmonella during concurrent malaria parasite infection. Sci Rep. 2015;5:14603.

Lokken KL, Stull-Lane AR, Poels K, Tsolis RM. Malaria parasite-mediated alteration of macrophage function and increased iron availability predispose to disseminated non-typhoidal Salmonella infection. Infect Immun. 2018;86:e00301–18.

Bahizire E, D’Alessandro U, Dramaix M, Dauby N, Bahizire F, Mubagwa K, et al. Malaria and iron load at the first antenatal visit in the rural south kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo: is iron supplementation safe or could it be harmful? Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2018;98:520–3.

Cherak SJ, Giesbrecht GF, Metcalfe A, Ronksley PE, Malebranche ME. The effect of gestational period on the association between maternal prenatal salivary cortisol and birth weight: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2018;94:49–62.

Vom Steeg LG, Klein SL. Sex steroids mediate bi-directional interactions between hots and microbes. Horm Behav. 2017;88:45–51.

Sandman CA, Glynn L, Schetter CD, et al. Elevated maternal cortisol early in pregnancy predicts third trimester levels of placental corticotropin releasing hormone (CRH): priming the placental clock. Peptides. 2006;27:1457–63.

Vleugels MP, Brabin B, Eling WM, De Graaf R. Cortisol and Plasmodium falciparum infection in pregnant women in Kenya. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1989;83:173–7.

Bouyou-Akotet MK, Adegnika AA, Agnandji ST, Ngou-Milama E, Kombila M, Kremsner PG, et al. Cortisol and susceptibility to malaria during pregnancy. Microbes Infect. 2005;7:1217–23.

Talati AN, Hackney DN, Mesiano S. Pathophysiology of preterm labor with intact membranes. Semin Perinatol. 2017;41:420–6.

Boyle AK, Rinaldi SF, Norman JE, Stock SJ. Preterm birth: inflammation, fetal injury and treatment strategies. J Reprod Immunol. 2017;119:62–6.

Lachelin GC, McGarrigle HH, Seed PT, Briley A, Shennan AH, Poston L. Low saliva progesterone concentrations are associated with spontaneous early preterm labour (before 34 weeks of gestation) in women at increased risk of preterm delivery. BJOG. 2009;116:1515–9.

Sacerdoti F, Amaral MM, Aisemberg J, Cymeryng CB, Franchi AM, Ibarra C. Involvement of hypoxia and inflammation in early pregnancy loss mediated by Shiga toxin type 2. Placenta. 2015;36:674–80.

Migale R, MacIntyre DA, Cacciatore S, Lee YS, Hagberg H, Herbert BR, et al. Modeling hormonal and inflammatory contributions to preterm and term labor using uterine temporal transcriptomics. BMC Med. 2016;14:86.

Aisemberg J, Vercelli CA, Bariani MV, Billi SC, Wolfson ML, Franchi AM. Progesterone is essential for protecting against LPS-induced pregnancy loss. LIF as a potential mediator of the anti-inflammatory effect of progesterone. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e56161.

Li X, Rhee DK, Malhotra R, Mayeur C, Hurst LA, Ager E, Shelton G, et al. Progesterone receptor membrane component-1 regulates hepcidin biosynthesis. J Clin Invest. 2016;126:389–401.

Brosens I, Ćurčić A, Vejnović T, Gargett CE, Brosens JJ, Benagiano G. The perinatal origins of major reproductive disorders in the adolescent: research avenues. Placenta. 2015;36:341–4.

Garcia-Ruíz G, Flores-Espinosa P, Preciado-Martínez E, Bermejo-Martínez L, Espejel-Nuñez A, Estrada-Gutierrez G, et al. In vitro progesterone modulation on bacterial endotoxin-induced production of IL-1β, TNFα, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, MIP-1α, and MMP-9 in pre-labor human term placenta. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2015;13:115.

Tremellen K, Syedi N, Tan S, Pearce K. Metabolic endotoxaemia—a potential novel link between ovarian inflammation and impaired progesterone production. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2015;31:309–12.

Wolfson ML, Schander JA, Bariani MV, Corres F, Franchi AM. Progesterone modulates the LPS-induced nitric oxide production by a progesterone-receptor independent mechanism. Eur J Pharmacol. 2015;769:110–6.

Flores-Espinosa P, Pineda-Torres M, Vega-Sánchez R, Estrada-Gutiérrez G, Espejel-Nuñez A, Flores-Pliego A, et al. Progesterone elicits an inhibitory effect upon LPS-induced innate immune response in pre-labor human amniotic epithelium. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2014;71:61–72.

Peters GA, Yi L, Skomorovska-Prokvolit Y, Patel B, Amini P, Tan H, Mesiano S. Inflammatory stimuli increase progesterone receptor-A stability and transrepressive activity in myometrial cells. Endocrinology. 2017;158:158–69.

Smith R, Paul J, Maiti K, Tolosa J, Madsen G. Recent advances in understanding the endocrinology of human birth. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2012;23:516–23.

Faro J, Romero R, Schwenkel G, Garcia-Flores V, Arenas-Hernandez M, Leng Y, Xu Y, et al. Intra-amniotic inflammation induces preterm birth by activating the NLRP3 inflammasome. Biol Reprod. 2019;100:1290–305.

Berry I, Walker P, Tagbor H, Bojang K, Coulibaly SO, Kayentao K, et al. Seasonal dynamics of malaria in pregnancy in West Africa: evidence for carriage of infections acquired before pregnancy until first contact with antenatal care. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2018;98:534–42.

Schmiegelow C, Matondo S, Minja DTR, Resende M, Pehrson C, Nielsen BB, et al. Plasmodium falciparum infection early in pregnancy has profound consequences for fetal growth. J Infect Dis. 2017;216:1601–10.

Cottrell G, Moussiliou A, Luty AJ, Cot M, Fievet N, Massougbodji A, et al. Submicroscopic Plasmodium falciparum infections are associated with maternal anemia, premature births, and low birth weight. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60:1481–8.

Ataíde R, Mayor A, Rogerson SJ. Malaria, primigravidae, and antibodies: knowledge gained and future perspectives. Trends Parasitol. 2014;30:85–94.

Fowkes FJI, Moore KA, Opi DH, Simpson JA, Langham F, Stanisic DI, et al. Iron deficiency during pregnancy is associated with a reduced risk of adverse birth outcomes in a malaria-endemic area in a longitudinal cohort study. BMC Med. 2018;16:156.

Muller IB, Hyde JE. Folate metabolism in human malaria parasites—75 years on. Mol Biochem Parasit. 2013;188:63–7.

Stieb DM, Lavigne E, Chen L, Pinault L, Gasparrini A, Tjepkema M. Air pollution in the week prior to delivery and preterm birth in 24 Canadian cities: a time to event analysis. Environ Health. 2019;18:1.

Harrison MS, Goldenberg RL. Global burden of prematurity. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016;21:74–9.

Okosun KO, Makinde OD. A co-infection model of malaria and cholera diseases with optimal control. Math Biosci. 2014;258:19–32.

Ng PY, Ireland DJ, Keelan JA. Drugs to block cytokine signaling for the prevention and treatment of inflammation-induced preterm birth. Front Immunol. 2015;6:166.

Van den Broek N, Jean-Baptiste R, Neilson JP. Factors associated with preterm, early preterm and late preterm birth in Malawi. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e90128.

Mwangi MN, Roth JM, Smit MR, Trijsburg L, Mwangi AM, Demir AY, et al. Effect of daily antenatal iron supplementation on Plasmodium infection in Kenyan women: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314:1009–20.

Kapisi J, Kakuru A, Jagannathan P, Muhindo MK, Natureeba P, Awori P, et al. Relationships between infection with Plasmodium falciparum during pregnancy, measures of placental malaria, and adverse birth outcomes. Malar J. 2017;16:400.

Unger HW, Hansa AP, Buffet C, Hasang W, Teo A, Randall L, et al. Sulphadoxine–pyrimethamine plus azithromycin may improve birth outcomes through impacts on inflammation and placental angiogenesis independent of malarial infection. Sci Rep. 2019;9:2260.

Delnord M, Blondel B, Zeitlin J. What contributes to disparities in the preterm birth rate in European countries? Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2015;27:133–42.

Van den Broek N, Ntonya C, Kayira E, White S, Neilson JP. Preterm birth in rural Malawi: high incidence in ultrasound dated population. Hum Reprod. 2005;20:3235–7.

Owens S, Gulati R, Fulford AJ, Sosseh F, Denison FC, Brabin BJ, et al. Periconceptional multiple-micronutrient supplementation and placental function in rural Gambian women: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;102:1450–9.

Acknowledgements

We thank the PALUFER Research Team; S. Gies of the Department of Biomedical Sciences, Prince Leopold Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp for field trial co-ordination; S. Diallo, of the Clinical Research Unit of Nanoro (URCN/IRSS), Nanoro, Burkina Faso, for completing CRP assays; Dorine Swinkels and AJ Geurts-Moespot of the Department of Laboratory Medicine (TLM 830), Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Center, Nijmegen, The Netherlands for completing hepcidin assays.

Funding

The National Institutes of Health USA, (Grant Number U01HD061234-01A1; Supplementary-05S1 and -02S2), the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and the National Institutes of Health Office of Dietary Supplements.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BB was the Principal Investigator for the main RCT on iron supplementation and is accountable for all aspects of the work. He wrote the draft paper. HT was a member of the scientific advisory committee and provided administrative, technical, and material support for the trial; SR was co-author and study statistician. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The clinical protocol was approved by the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, UK, Research Ethics Committee (LSTM/REC Research Protocol 10.55. Dec 2010); the Institutional Review Board of the Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp, Belgium (IRB/AB/AC/016. February 2011); the Antwerp University Hospital Ethics Committee (EC/UZA. February 2011); in Burkina Faso the Institutional Ethics Committee of Centre Muraz (Comité d’Ethique Institutionnel du Centre Muraz, and the National Ethics Committee (Comité Ethique pour la Recherche en Santé, CERS. Ref 015-2010/CE-CM. January 2011). All participants provided informed consent in line with the Declaration of Helsinki, and consent procedures have been previously detailed [92].

Consent for publication

All participants gave consent for publication of research findings.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 2.

Laboratory methods. Summary of laboratory methods used for CRP, hepcidin assays and malaria microscopy.

Additional file 3.

Gestational age distribution in days of livebirths in iron and control arms. Vertical stippled lines indicate 43 weeks and 37 weeks gestation.

Additional file 4.

Path modelling of PTB and gestation. Outline of Path Model, statistical methodology and results. Figures S1. (Path Model); Figure S2. (the fitted relationship between CRP and hepcidin); Table S1. (Path model coefficients).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Brabin, B., Tinto, H. & Roberts, S.A. Testing an infection model to explain excess risk of preterm birth with long-term iron supplementation in a malaria endemic area. Malar J 18, 374 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-019-3013-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-019-3013-6