Abstract

Background

Respiratory complications are uncommon, but often life-threatening features of Plasmodium vivax malaria. This study aimed to estimate the prevalence and lethality associated with such complications among P. vivax malaria patients in a tertiary hospital in the Western Brazilian Amazon, and to identify variables associated with severe respiratory complications, intensive care need and death. Medical records from 2009 to 2016 were reviewed aiming to identify all patients diagnosed with P. vivax malaria and respiratory complications. Prevalence, lethality and risk factors associated with WHO defined respiratory complications, intensive care need and death were assessed.

Results

A total of 587 vivax malaria patients were hospitalized during the study period. Thirty (5.1%) developed respiratory complications. Thirteen (43.3%) developed severe respiratory complications, intensive care was required for 12 (40%) patients and 5 (16.6%) died. On admission, anaemia and thrombocytopaenia were common findings, whereas fever was unusual. Patients presented different classes of parasitaemia and six were aparasitaemic on admission. Time to respiratory complications occurred after anti-malarials administration in 18 (60%) patients and progressed very rapidly. Seventeen patients (56.7%) had comorbidities and/or concomitant conditions, which were significantly associated to higher odds of developing severe respiratory complications, need for intensive care and death (p < 0.05).

Conclusion

Respiratory complications were shown to be associated with significant mortality in this population. Patients with comorbidities and/or concomitant conditions require special attention to avoid this potential life-threatening complication.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Malaria remains a major public health problem in endemic countries. Despite advances in control and elimination strategies, recent estimates by the World Health Organization (WHO) highlight its high morbidity and mortality. While the majority of malaria deaths are attributed to Plasmodium falciparum, it is now widely accepted that Plasmodium vivax, the most geographically widespread human malaria parasite (~ 8.5 million annual cases) may also cause severe disease, associated with 3000 annual deaths globally [1]. Despite clinical evidence of severity from the inoculation of essentially ‘non-severe’ P. vivax strains during malariotherapy studies during in the 1930s [2], the recognition of vivax associated severity and its associated multi-organ dysfunction is relatively new [3,4,5,6,7,8]. This historical lack of attention by the global community of malariologists may have hampered more effective policies against malaria. Factors associated with geographical dispersion of vivax infection are complex, especially regarding the prevalence of severe syndromes and fatal disease [9], with those in lower and unstable transmission settings, as in the Americas, presenting a wider variety of organ dysfunctions [10]. Underlying conditions and comorbidities have long been perceived as having a negative impact on vivax malaria outcomes. An autopsy series conducted among confirmed vivax infected individuals revealed that 76% of them presented some type of underlying condition [6]. In that study, 41% had developed lung complications [6]. However, no clear information is available regarding the general epidemiology, risk factors and prevalence of respiratory complications in vivax malaria, especially in the Brazilian Amazon.

A recent meta-analysis showed that the prevalence of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) among vivax malaria cases ranged between 2.2% (adults) and 2.8% (children), with nearly 50% mortality, confirming the significance and associated poor prognosis of this type of complication among P. vivax malaria patients [11]. Moreover, female sex, having any comorbidity, lower body temperature, lower haemoglobin, and low oxygen saturation values (hypoxaemia) were significantly associated with mortality. However, as only studies containing respiratory complications were included, the prevalence of respiratory complications may have been overestimated. Similarly, population-based studies are rarely reported in the literature, leading to a possible publication bias. The aims of this study were to estimate the prevalence and lethality of such complications among P. vivax malaria patients in the Western Brazilian Amazon and to identify variables associated with the development of severe respiratory complications according to WHO definitions, need for intensive care (ICU) and death.

Methods

Study site and case management

The Fundação de Medicina Tropical Doutor Heitor Vieira Dourado (FMT-HVD) is a tertiary care centre in Manaus (Western Brazilian Amazon) and a reference institution for infectious diseases in the north region of the country. Patients may either directly seek care at the hospital’s outpatient clinic or be referred from other local hospitals and surrounding municipalities. At hospital presentation, patients with fever, or history of fever in the preceding days, are tested for malaria by thick blood smear. Admission/arrival to the hospital may happen after microscopic diagnosis and treatment initiation at primary level of health-care. Patient data are registered in the hospital’s electronical medical charts (iDoctor®). Once at the hospital, all patients undergo medical consultation and a 7-day post treatment initiation follow-up visit if diagnosed with malaria. Patients presenting with any severe clinical sign according to WHO severe malaria definitions (impaired consciousness, jaundice, significant bleeding, shock, respiratory distress and others) [12] are immediately referred to the emergency department and managed accordingly. Additional investigation for concomitant infections is triggered by the presence of specific manifestations and/or at medical’s discretion through clinical investigation and routine blood and urine testing. Comorbidities are sought based on patient’s provided information and medical chart assessment. G6PD deficiency is not tested systematically.

Malaria diagnosis and treatment

In Brazil, thick blood smears are routinely performed for malaria diagnosis and occur at different health posts in the primary level of health care. All malaria tests (positive and negative) are recorded in the national epidemiological surveillance system for malaria (SIVEP), implemented by the Brazilian National Ministry of Health in 2002. Slides are read by local microscopists and results are given following a semi-quantitative system: 1/2 + (200–300 parasites/mm3); 1 + (301–500 parasites/mm3); 2 + (501–10,000 parasites/mm3); 3 + (10,001–100,000 parasites/mm3); and 4 + (> 100,001 parasites/mm3). All positive slides and 10% of negative slides are routinely reviewed in a reference unit by senior microscopists. In case of divergence, the reviewed reading is updated in the SIVEP system. PCR diagnosis is not routinely performed for malaria diagnosis. Treatment is only provided after a positive smear for malaria. Anti-malarial treatment for P. vivax malaria occurs following WHO recommendations and Brazilian guidelines with chloroquine (CQ, 25 mg/kg divided in 3 days) for uncomplicated cases, or parenteral artemether or artesunate in patients suspected of severe malaria or severe vomiting, followed by primaquine (PQ, 3.5 mg/kg in 7 or 14 days) [13, 14].

Study design, population and data collection

A retrospective search of charts was performed using the International Classification of Diseases aiming to identify all patients diagnosed with P. vivax malaria who were hospitalized. After identification, all were completely screened for respiratory complications prior to hospital presentation, upon admission or during hospitalization. These included respiratory complaints reported by the patient in the previous days to hospital presentation or at hospital presentation or by medical examination at admission or during the hospitalization period. All clinical and laboratory information was then retrieved from the patient’s medical chart using a structured questionnaire completed by two independent investigators of the study. Data regarding parasitaemia, time of diagnosis, time of treatment start and anti-malarials used were also collected if available. Fever data (axillary temperature > 37.5 °C) was also collected if available. Patients anonymity was preserved through the analysis. No restriction of age was applied.

Respiratory complications and case definition

Respiratory distress (RD) was defined as the following: respiratory rate > 30/min and oxygen saturation < 92% on room air in adults [12] or respiratory rate > 40/min (children 12 months up to 5 years) or > 50/min (children aged from 2 to 12 months) and oxygen saturation < 90% [15]. Blood gas analysis was also used to further assist diagnosis and management when available. Both vivax and falciparum malaria share the same criteria for severe disease with exclusion of parasitaemia thresholds [12]. Severe WHO definitions for severe respiratory impairment in malaria, including acidotic breathing and pulmonary oedema (PE) were used [12]. Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) following Berlin definition was also used [16]. Definitions are presented in Table 1.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using independent t tests, Wilcoxon Mann–Whitney or χ2 tests to compare variables across groups stratified by three independent outcomes (development of severe respiratory impairment composed by patients presenting PE and/or ARDS; patients in need for intensive care support and those who died). Difference in proportions were tested by Chi squared test (corrected by Fisher’s test if necessary). Odds ratio (OR) with its 95% confidence interval (CI) was calculated for association between variables and outcomes using logistic regression. The diagnostic performance of laboratorial parameters for the three outcomes was assessed by means of receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. Significance was set as p < 0.05. Analyses were performed using STATA version 12.1 (Stata Corp LP, Texas USA). The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement was used as guidelines for reporting this study (Additional file 1) [17].

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the Ethics Review Board (ERB) of FMT-HVD, Manaus, Brazil (1943/2008) and the National Brazilian Committee of Ethics (CONEP) (343/2009). All data analysed were anonymous. Since data was obtained exclusively from the medical charts, the ERB gave a waiver of informed consent.

Results

Prevalence and lethality of respiratory complications

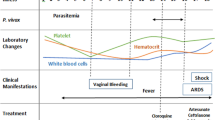

From 2009 to 2016, 25,225 cases were diagnosed with malaria in the FMT-HVD, of which 24,225 (96%) were positive for P. vivax. A total of 587 P. vivax malaria patients were hospitalized. Of these, 30 (5.1%) were documented to have respiratory complications. Overall prevalence of respiratory complications was 0.1% among all vivax malaria episodes in this period. Prevalence of severe respiratory complications among hospitalized patients was 43.3% (13 patients). Twelve (40%) needed intensive care management and 5 patients (16.6%) died (Fig. 1).

General characteristics of patients with respiratory complications

Epidemiological and clinical characteristics, treatments, parasitaemia, disease progression and outcome of all 30 cases are summarized in Table 2. Summary data is presented in Table 3. Seventeen (56.6%) patients presented previous history of malaria infections. Twenty-six (80%) patients received CQ for malaria treatment, with PQ association in 21 (70%). Fifteen (50%) patients had started anti-malarial treatment before hospitalization. Eighteen patients (60%) developed respiratory complications after anti-malarial start. Seventeen (56.6%) presented comorbidities (diabetes mellitus type 2, systemic hypertension, myasthenia gravis) and/or co-infections (HIV, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Streptococcus pneumoniae bacteremia, detected by blood analysis). Two female patients were pregnant (Table 2). Patients with comorbidities were older than those without such conditions (45.8 ± 18.4 vs 23.7 ± 17.4, respectively; p = 0.006). G6PD deficiency was suspected after severe haemolysis associated to history of PQ treatment and was further confirmed in 5 (16.6%) patients. Haemodialysis was necessary in 5 (16.6%) patients (Table 2). Anaemia and thrombocytopaenia were common laboratory findings on admission exams (Table 2). Eleven (36.6%) patients had some degree of multi-organ involvement: 5 (16.6%) patients presented haemoglobin < 7 g/dL, four (13.3%) presented creatinine > 3 mg/dL, six (10%) presented impaired consciousness, five presented shock (16.6%) and 1 (3.3%) presented hypoglycemia (Table 2). Fifteen patients presented platelet count below 50,000/mm3; 12 presented platelet counts between > 50,000 and ≤ 150,000/mm3 and three with platelet count > 150,000/mm3 (Table 2).

Parasitaemia

Twelve patients (40%) reported having started anti-malarial treatment before hospital presentation due to positive malaria diagnosis in the previous days. A total of 6 patients (20%) were already aparasitaemic at hospital admission, 5 (16.6%) patients presented one cross parasitaemia, 11 (36.7%) presented 2 crosses and 8 (26.7%) presented 3 crosses.

Severe respiratory complications

Of the 30 patients with a respiratory complication, 13 (43.3%) patients developed severe respiratory complications (PE and/or ARDS). The proportion of patients presenting comorbidities and/or concomitant conditions was significantly increased in this group (p = 0.001). Four patients died. Lung deterioration occurred after anti-malarials in nine patients (69.2%) of this group and progressed rapidly in some cases. Further results are presented in Table 3. Radiological findings (including alveolar infiltrates and diffuse patchy bilateral opacities) of three cases developing ARDS are presented Fig. 2.

Radiological findings of three patients with P. vivax malaria who developed ARDS. A Progressed with acute renal failure, severe anaemia, disseminated intravascular coagulation and coma. Arrived intubated (D0), blood transfusion (D2), convulsions (D12), haemodialysis (D13) and died (D14). B Progressed with acute renal failure, hyperbilirubinemia and shock. Hospitalization (D0), intubated (D8) and discharged (D28). C G6PD deficient (acute haemolysis after PQ). Progressed with shock and died in the following 24 h

Comorbidities and concomitant conditions [OR 9.2 (95% CI 1.3–113.2); p = 0.017] and having initiated anti-malarial treatment before hospitalization [OR 7.3 (95% 1.2–60.9); p = 0.025] were associated with higher odds of developing severe respiratory complications. Previous malaria infections, haemoglobin, platelets, leucocytes and other variables were not associated to developing severe respiratory complications in these patients. Complete results of univariate analysis for risk factors and development of severe respiratory complications are presented in Additional file 2: Table S1.

ROC analysis was performed in order to depict the discriminatory performance of laboratory variables for patients developing severe respiratory complications. Platelets [AUC 0.783 (95% CI 0.608–0.958), cut point 66000 (78.8% sensitivity; 82.3% specificity)] and leucocytes [AUC 0.781 (95% CI 0.607–0.954)] presented with reasonable discriminative performance for developing severe respiratory complications (Additional file 5: Table S4).

Intensive care and death

Twelve (40%) patients needed intensive care support. Analysis revealed that these patients presented comorbidities and/or concomitant conditions (33.3% vs 91.6%, p = 0.002) more frequently and had lower haemoglobin values at admission (10.2 ± 0.4 g/dL vs 8.5 ± 0.6 g/dL, p = 0.003). Also, creatinine and urea at admission were found to be significantly elevated in this group, with four (33.3%, p = 0.046) patients requiring further haemodialysis (Table 4).

The group composed by patients who died (n = 5, 16.6%) was older (32 ± 4 vs 54 ± 8, p = 0.042). Prevalence of comorbidities and/or concomitant conditions was significant (48% vs 100%, p = 0.032). Lower levels of haemoglobin (p = 0.037), higher levels of urea (p = 0034) and lactate dehydrogenase enzyme (p < 0.001) and also a higher proportion of patients (three, 60%, p = 0.004) requiring haemodialysis was observed. Results are presented in Table 4.

Comorbidities and/or concomitant conditions [OR 19.6 (95% CI 2–1023); p = 0.003] and creatinine [OR 3.4 (95%1.2–13.3); p = 0.009 were significantly associated with higher odds for intensive care need (complete results are presented in Additional file 3: Table S2). Haemodialysis [OR 14.5 (95% CI 1–289.7); p = 0.021] was significantly associated to higher odds of death (complete results are presented in Additional file 4: Table S3).

Receiver operating curve analysis was performed in order to depict the discriminatory performance of baseline laboratory variables for patients that needed intensive care and for those who died. Results from ROC analysis for intensive care need outcome showed that urea [AUC 0.81 (95% CI 0.63–0.959), cut point 45 (66.7% sensitivity; 94.1% specificity)] and creatinine [AUC 0.74 (95% CI 0.54–0.95), cut point 1.5 (58.3% sensitivity; 94.1% specificity)] presented reasonable discriminative performance for this outcome. When stratification was performed for final outcome (patients discharged alive or those who died), lactate dehydrogenase [AUC 0.88 (95% CI 0.64–1), cut point 1389 (55% sensitivity; 100% specificity)] and bilirubin [AUC 0.81 (95% CI 0.43–1), cut point 12.7 (75% sensitivity; 100% specificity)] presented reasonable discriminative performance. Results are presented in Additional file 5: Table S4.

Discussion

Data from medical charts of 30 cases of hospitalized vivax malaria patients that developed respiratory complications in a tropical disease hospital of the western Brazilian amazon, between 2009 and 2016, were collected retrospectively. Anaemia and thrombocytopaenia at admission were common findings among these patients. Comorbidities and/or concomitant conditions were present in more than half of the studied population. Severe WHO defined respiratory complications and multi-organ failure developed in several cases with intensive care being necessary. Reported anti-malarial regimen consisted mainly of CQ plus PQ with a more than half of patients developing respiratory complications after treatment start.

A pooled analysis of clinical studies since the year 1900 describing complications in vivax patients showed a 0.27% prevalence of respiratory dysfunction in reports with and without severity signs [10]. Geographical stratification has shown that prevalence estimates of respiratory complications vary according to endemic regions [11], mostly due to a complex interplay of host and vector characteristics [9]. Nonetheless, part of the variation is because of definitions used to describe these respiratory complications. In the present study, prevalence of ARDS and other severe respiratory complications were found to be equivalent to studies of similar design originating from India [18,19,20,21] and other countries from South-East Asia, the Eastern Mediterranean and the Western-Pacific regions [22,23,24,25,26].

The presence of comorbidities and concomitant conditions and the extent they contribute to complicated disease and death in malaria has lingered for centuries and still remains a matter of debate. A recent study from India with 511 P. vivax patients showed no significant difference in the presence of non-infectious comorbidities between severe and non-severe patients [27]. On the other hand, a study conducted in India and Brazil with 778 patients showed that patients with comorbidities may present higher risk of complications and death [8]. Also, four out of seven patients with respiratory complications presented comorbidities in the Brazilian autopsy series [6]. Despite evidence of association between comorbidities and severe disease, this still needs elucidation in vivax malaria. It is hypothesized that comorbidities, co-infections and other concomitant conditions may become unstable due to anaemia and fever in acute vivax infections. Thus, a concurrent acute or chronic relatively controlled condition can lead to a severe and potentially life-threatening one through hypoxia exacerbation and haemodynamic decompensation [28].

G6PDd screening is not routinely performed in the Americas for vivax malaria placing this population at a high risk for haemolysis [29]. In the present study, five patients were screened for G6PD activity according to medical discretion. Due to this, G6PD status is unknown in the other patients. The precise pathogenic mechanisms involving G6PD deficiency, primaquine-induced haemolysis and the development of respiratory complications in vivax malaria deserves more research and elucidation.

Several studies have reported cases of respiratory complications in vivax malaria after treatment [11], with a tenfold increase in the risk for developing respiratory distress [8]. It is suggested that a post-treatment inflammatory phenomenon occurs within lung microvasculature in these cases leading to respiratory impairment [30, 31]. This study has shown a possible association between treatment initiation and respiratory impairment. Importantly, chloroquine is known to have immune-modulatory proprieties [32,33,34], which could further prevent worsening of post-treatment inflammation and associated symptoms. Nonetheless, after taking into account increasing chloroquine-resistance, a change to artemisinin combination therapies for Plasmodium blood stage killing, which does not have an anti-inflammatory profile, could further increase the number of post-treatment inflammatory complications in vivax patients, such as respiratory distress [35]. Studies addressing this specific aspect of anti-malarial treatment switch are urgently needed.

The few published histopathological analyses in vivax malaria have revealed infiltrates of monocytes, lymphocytes, and neutrophils in pulmonary microvasculature along with phagocytosed pigment and diffuse alveolar damage [36, 37] and hyaline membrane formation [38]. Severe alveolar oedema and congestion with infiltrates containing mononuclear cells and suggestive images of adhesion of Plasmodium-infected red cells to lung microvasculature have also been reported [39]. In P. vivax malaria, cytoadhesion of parasitized red blood cells also seems to occur, but to a much lesser extent and magnitude to what can be seen in P. falciparum [40, 41]. Additionally, peripheral parasitaemia is generally much lower in this species, due to the preferential invasion of reticulocytes [38]. Instead the relatively much greater inflammatory and endothelial activation, as revealed by elevated cytokines and other inflammatory-inducing molecules [42,43,44], may be responsible for alveolar-capillary barrier loss and increased permeability [38], and is probably the basis for the particular respiratory complications in this species, as seen here.

This study has limitations that need to be addressed. The authors decided to focus on respiratory complications of P. vivax malaria and provide a more comprehensive description of its associated clinical manifestations in detriment of comparing epidemiological, clinical and laboratory aspects between this type of complication and other WHO-defined severe malaria syndromes. Therefore, no risk factor for developing respiratory complications in comparison to other malaria related complications were assessed. The retrospective nature of this study accounts for incomplete data collection due to a lack of prospective and detailed targeted investigation, including proper registration of respiratory rates, which may lead to underestimation of the prevalence of this complication, accurate registration of oxygenation rates and mechanical ventilation parameters, which may lead to lack of proper classification of ARDS according to the Berlin definition and also proper malaria diagnosis through molecular methods and systematic co-infection screening and comorbidity investigation. The decision to admit patients was made at the attending physician’s discretion and may have resulted in selection bias, which was minimized through adoption of WHO severe malaria criteria. A great number of patients in this study had received anti-malarial treatment prior to hospital presentation with some of them presenting aparasitaemic, or probably with declining parasitaemia, at the time of admission. This could implicate in clinical improvement at this time and may have underestimated the rate of respiratory complication. In addition, the relatively low prevalence of respiratory complications, and therefore, the small sample size in this study does not support more robust predictive analyses, which may further hamper translational implications. Furthermore, pathogenic mechanisms of respiratory deterioration development could not be explored with such a study design.

Conclusions

Respiratory complications were found to have low prevalence among all vivax episodes in this study. Despite that, this complication was found to be a frequent clinical exacerbation among P. vivax malaria cases in need for hospital care. Comorbidities and/or concomitant conditions occurred in older patients, were associated with worsening of cases and remained associated to elevated odds for severe respiratory complication development, intensive care need and death. In this case, age may have influenced the presence of comorbidities, and therefore, be associated to poor outcome. Nonetheless, the presence of comorbidities, but not age, directly influenced the poor outcome in this study. The results from this study points to the importance of properly recognizing the existence of complications in vivax malaria infection, especially in patients with associated comorbidities and/or concomitant conditions, and further supports rebutting the old paradigm that it does not cause important and lethal disease. Prospective studies are needed to better address this potentially dangerous clinical complication and the association between chronic, non-infectious and infectious comorbidities, severe and fatal P. vivax infections.

Abbreviations

- ARDS:

-

acute respiratory distress syndrome

- FMT-HVD:

-

Fundação de Medicina Tropical Doutor Heitor Vieira Dourado

- G6PD:

-

glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase

- ICU:

-

intensive care unit

- PE:

-

pulmonary oedema

- ROC:

-

receiver operating curve

- RD:

-

respiratory distress

- SIVEP:

-

national epidemiological surveillance system for malaria

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

WHO. World malaria report 2016. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016.

Austin SC, Stolley P, Lasky T. The history of malariotherapy for neurosyphilis. JAMA. 1992;268:516.

Genton B, D’Acremont V, Rare L, Baea K, Reeder JC, Alpers MP, et al. Plasmodium vivax and mixed infections are associated with severe malaria in children: a prospective cohort study from Papua New Guinea. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e127.

Tjitra E, Anstey NM, Sugiarto P, Warikar N, Kenangalem E, Karyana M, et al. Multidrug-resistant Plasmodium vivax associated with severe and fatal malaria: a prospective study in Papua, Indonesia. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e128.

Manning L, Laman M, Law I, Bona C, Aipit S, Teine D, et al. Features and prognosis of severe malaria caused by Plasmodium falciparum, Plasmodium vivax and mixed Plasmodium species in Papua New Guinean children. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e29203.

Lacerda MVG, Fragoso SCP, Alecrim MGC, Alexandre MA, Magalhães BML, Siqueira AM, et al. Postmortem characterization of patients with clinical diagnosis of Plasmodium vivax malaria: to what extent does this parasite kill? Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:e67–74.

Saravu K, Rishikesh K, Kamath A, Shastry AB. Severity in Plasmodium vivax malaria claiming global vigilance and exploration—a tertiary care centre-based cohort study. Malar J. 2014;13:304.

Siqueira AM, Lacerda MVG, Magalhães BML, Mourão MPG, Melo GC, Alexandre MA, et al. Characterization of Plasmodium vivax-associated admissions to reference hospitals in Brazil and India. BMC Med. 2015;13:57.

Howes RE, Battle KE, Mendis KN, Smith DL, Cibulskis RE, Baird JK, et al. Global epidemiology of Plasmodium vivax. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2016;95(Suppl 6):15–34.

Rahimi BA, Thakkinstian A, White NJ, Sirivichayakul C, Dondorp AM, Chokejindachai W. Severe vivax malaria: a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical studies since 1900. Malar J. 2014;13:481.

Val F, Machado K, Barbosa L, Salinas JL, Siqueira AM, Alecrim MGC, et al. Respiratory complications of Plasmodium vivax malaria: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2017;97:733–43.

WHO. Severe malaria. Trop Med Int Health. 2014;19(Suppl 1):7–131.

Ministério da Saúde. Guia prático de tratamento da malária no Brasil. 2010.

WHO. Guidelines for the treatment of malaria. 3rd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015.

WHO. Integrated management of childhood illness: chart booklet. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014.

ARDS Definition Task Force, Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, Thompson BT, Ferguson ND, Caldwell E, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome. JAMA. 2012;307:2526–33.

Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61:344–9.

Kochar DK, Das A, Kochar SK, Saxena V, Sirohi P, Garg S, et al. Severe Plasmodium vivax malaria: a report on serial cases from Bikaner in northwestern India. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;80:194–8.

Limaye CS, Londhey VA, Nabar ST. The study of complications of vivax malaria in comparison with falciparum malaria in Mumbai. J Assoc Phys India. 2012;60:15–8.

Rizvi I, Tripathi DK, Chughtai AM, Beg M, Zaman S, Zaidi N. Complications associated with Plasmodium vivax malaria: a retrospective study from a tertiary care hospital based in western Uttar Pradesh, India. Ann Afr Med. 2013;12:155–9.

Jain A, Kaushik R, Kaushik RM. Malarial hepatopathy: clinical profile and association with other malarial complications. Acta Trop. 2016;159:95–105.

Barber BE, William T, Grigg MJ, Menon J, Auburn S, Marfurt J, et al. A prospective comparative study of knowlesi, falciparum, and vivax malaria in Sabah, Malaysia: high proportion with severe disease from Plasmodium knowlesi and Plasmodium vivax but no mortality with early referral and artesunate therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56:383–97.

Habib AG, Singh KS. Respiratory distress in nonimmune adults with imported malaria. Infection. 2004;32:356–9.

Kotwal RS, Wenzel RB, Sterling RA, Porter WD, Jordan NN, Petruccelli BP. An outbreak of malaria in US Army Rangers returning from Afghanistan. JAMA. 2005;293:212–6.

Chung SJ, Low JGH, Wijaya L. Malaria in a tertiary hospital in Singapore–clinical presentation, treatment and outcome: an 11 year retrospective review. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2014;12:738–44.

Nurleila S, Syafruddin D, Elyazar IRF, Baird JK. Serious and fatal illness associated with falciparum and vivax malaria among patients admitted to hospital at West Sumba in Eastern Indonesia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012;87:41–9.

Kumar R, Saravu K. Severe vivax malaria: a prospective exploration at a tertiary healthcare centre in Southwestern India. Pathog Glob Health. 2017;111:148–60.

Anstey NM, Russell B, Yeo TW, Price RN. The pathophysiology of vivax malaria. Trends Parasitol. 2009;25:220–7.

Recht J, Siqueira AM, Monteiro WM, Herrera SM, Herrera S, Lacerda MVG. Malaria in Brazil, Colombia, Peru and Venezuela: current challenges in malaria control and elimination. Malar J. 2017;16:273.

Anstey NM, Jacups SP, Cain T, Pearson T, Ziesing PJ, Fisher DA, et al. Pulmonary manifestations of uncomplicated falciparum and vivax malaria: cough, small airways obstruction, impaired gas transfer, and increased pulmonary phagocytic activity. J Infect Dis. 2002;185:1326–34.

Anstey NM, Handojo T, Pain MCF, Kenangalem E, Tjitra E, Price RN, et al. Lung injury in vivax malaria: pathophysiological evidence for pulmonary vascular sequestration and posttreatment alveolar-capillary inflammation. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:589–96.

Karres I, Kremer J-P, Dietl I, Steckholzer U, Jochum M, Ertel W. Chloroquine inhibits proinflammatory cytokine release into human whole blood. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 1998;274:R1058–64.

Jang C-H, Choi J-H, Byun M-S, Jue D-M. Chloroquine inhibits production of TNF-alpha, IL-1beta and IL-6 from lipopolysaccharide-stimulated human monocytes/macrophages by different modes. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2006;45:703–10.

Thomé R, Moraes AS, Bombeiro AL, dos Santos Farias A, Francelin C, da Costa TA, et al. Chloroquine treatment enhances regulatory T cells and reduces the severity of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e65913.

Douglas NM, Anstey NM, Angus BJ, Nosten F, Price RN. Artemisinin combination therapy for vivax malaria. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10:405–16.

Bustos MM, Gómez R, Álvarez CA, Valderrama S, Támara JR. Adult acute respiratory distress syndrome by Plasmodium vivax. Acta Médica Colombiana. 2014;39:211–5.

Martínez O. Síndrome de dificultad respiratoria aguda en por Plasmodium vivax. Acta Médica Colombiana. 1996;21:146–50.

Valecha N, Pinto RGW, Turner GDH, Kumar A, Rodrigues S, Dubhashi NG, et al. Histopathology of fatal respiratory distress caused by Plasmodium vivax malaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;81:758–62.

Lacerda MVG, Fragoso SCP, Alecrim MGC, Alexandre MAA, Magalhães BML, Siqueira AM, et al. Postmortem characterization of patients with clinical diagnosis of Plasmodium vivax malaria: to what extent does this parasite kill? Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:67–74.

Carvalho BO, Lopes SCP, Pa Nogueira, Orlandi PP, Bargieri DY, Blanco YC, et al. On the cytoadhesion of Plasmodium vivax-infected erythrocytes. J Infect Dis. 2010;202:638–47.

Lopes SCP, Albrecht L, Carvalho BO, Siqueira AM, Thomson-Luque R, Nogueira PA, et al. Paucity of Plasmodium vivax mature schizonts in peripheral blood is associated with their increased cytoadhesive potential. J Infect Dis. 2014;209:1403–7.

Yeo TW, Da Lampah, Tjitra E, Piera K, Gitawati R, Kenangalem E, et al. Greater endothelial activation, Weibel-Palade body release and host inflammatory response to Plasmodium vivax, compared with Plasmodium falciparum: a prospective study in Papua, Indonesia. J Infect Dis. 2010;202:109–12.

Barber BE, William T, Grigg MJ, Parameswaran U, Piera KA, Price RN, et al. Parasite biomass-related inflammation, endothelial activation, microvascular dysfunction and disease severity in vivax malaria. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1004558.

Hemmer CJ, Holst FGE, Kern P, Chiwakata CB, Dietrich M, Reisinger EC. Stronger host response per parasitized erythrocyte in Plasmodium vivax or ovale than in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Trop Med Int Health. 2006;11:817–23.

Authors’ contributions

FV, AAG and SA were responsible for the data collection from medical records. FV and WMM performed the statistical analysis and wrote the first manuscript draft. FV, AMS, QB, MGCA, WMM and MVGL participated in study design, coordination and elaborated the final version of manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mr. Marco Saboia for help with data gathering and Judith Recht for reviewing English language. We also acknowledge the collaboration of the FMT-HVD medical statistics staff.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated from this study are included in the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Review Board (ERB) of FMT-HVD, Manaus, Brazil (1943/2008) and the National Brazilian Committee of Ethics (CONEP) (343/2009). All data analysed were anonymous. Since data was obtained exclusively from the medical charts, the ERB gave a waiver of informed consent.

Funding

This work was mainly supported by Fundació Cellex, and also by PRONEX Malaria Network, funded by the Brazilian Ministry of Science and Technology (MCT), the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), the Brazilian Ministry of Health (DECIT/SCTIE/MS), and the Research Support Foundation of Amazonas (FAPEAM) (Grant 555.666/2009-3). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional files

12936_2017_2143_MOESM5_ESM.docx

Additional file 5: Table S4. AUC of ROC depicting discriminatory performance of baseline laboratorial data according to outcome.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Val, F., Avalos, S., Gomes, A.A. et al. Are respiratory complications of Plasmodium vivax malaria an underestimated problem?. Malar J 16, 495 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-017-2143-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-017-2143-y