Abstract

Background

Women exposed to Plasmodium infection develop antibodies and become semi-immune. This immunity is suppressed during pregnancy making both the pregnant woman and the foetus vulnerable to the adverse effects of malaria, particularly by Plasmodium falciparum. Intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy (IPTp) with Sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine (SP) tablets is one of the current interventions to mitigate the effects of malaria on both the pregnant woman and the unborn child. The extent to which IPTp may interfere with the acquisition of protective immunity against pregnancy-associated malaria (PAM) is undefined in Ghana.

Methods

Three-hundred-and-twenty pregnant women were randomly enrolled at the antenatal clinic (ANC) in Madina, Accra. Venous blood samples were obtained at first ANC registration and at 4-week intervals (post-IPTp administration). Placental and cord blood samples were obtained at delivery and the infants were followed monthly for 6 months after birth. Anti-IgG and IgM antibodies against a crude antigen preparation and the glutamate-rich protein (GLURP) of P. falciparum were quantified by the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

Results

There was a general decline in the trend of mean concentrations of all the antibodies from enrolment to delivery. The levels of antibodies in cord blood and placenta were well correlated. Children did not show clinical signs of malaria at 6 months after birth.

Conclusions

IgG against both crude antigen and GLURP were present in placenta and cord blood and it is therefore concluded that there is a trend of declining antibody from enrolment to delivery and IPTp-SP may have reduced malaria exposure, however, this does not impact on the transfer of antibodies to the foetus in utero. The levels of maternal and cord blood antibodies at delivery showed no adverse implications on malaria among the children at 6 months. However, the quantum and quality of the antibody transferred needs further investigation to ensure that the infants are protected from severe episodes of malaria.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

About 50 million women who become pregnant in malaria-endemic regions each year [1] are infected with Plasmodium parasite [2]. Pregnant women are three times more likely to suffer from severe disease from malarial infection than their non-pregnant counterparts, with close to 50% mortality rate from severe disease [3]. Malaria, particularly Plasmodium falciparum infection increases the risk of maternal anaemia and other complications in pregnancy, often leading to abortions and stillbirths [4].

In general, immunity to P. falciparum develops slowly and naturally [5, 6] after repeated exposure [7,8,9,10]. The acquired anti-Plasmodium antibodies confer protective immunity [11], which reduces morbidity [12,13,14]. However, clinical immunity to malaria is partial and short-lived, and requires constant ‘longitudinal exposure’ to parasites to be maintained [9].

Despite acquiring partial immunity after years of exposure to Plasmodium, pregnant women become highly susceptible to P. falciparum due to the absence of immunity to pregnancy-specific isolates that sequester in the placenta [2, 15] resulting in long-standing placental malaria even when peripheral blood may be negative for malaria parasites, especially during the second trimester [16].

The parasites that infect the placenta have a special affinity to accumulate in the erythrocytes in the blood spaces of the placenta [17] and also characteristically bind to the placental ligand, chondroitin sulfate A (CSA) [18, 19]. A protective anti-CSA antibody-mediated immunity to pregnancy-associated malaria (PAM) develops after repeated exposure of the placenta to parasites. The multigravidae, who have developed anti-CSA from previous exposure, are less susceptible to PAM than the primigravidae who are experiencing the placenta for the first time [20, 21]. PAM can affect placenta development and function, leading to deleterious outcome to both mother and her infant [22,23,24], which further increases the risk for neonatal and infant mortality [25, 26]. Infection of the placenta by malaria parasites has been found to have no effect on the transmission of maternal antibodies to infants [27].

Another reason for the high susceptibility of pregnant women is attributed to various hormonal and immunological changes during pregnancy, with a leaning from cell-mediated immunity to humoral immunity. Primigravidae have higher levels of cortisol than multigravidae and therefore lose their acquired immunity more frequently and this increases their susceptibility to P. falciparum infection. These problems are more common in the first and second pregnancies since the parasitaemia level generally decreases with increasing numbers of pregnancies. In Ghana, malaria during pregnancy increases maternal anaemia and low birth weight (LBW), especially in women living in rural communities [28,29,30].

Newborn infants in endemic areas are markedly resistant to falciparum malaria due to protection from high levels of maternal anti-malarial immunoglobulin G (IgG) passively transferred across the placenta [31]. Congenital malaria is therefore rare in endemic areas but infants may present with parasitaemia within 2–3 months as the maternal acquired antibodies wane [32]. There is therefore a gradual acquisition of IgG to variant surface antigens (VSAs) after birth, while protection from maternal VSA-specific IgG steadily declines [33]. These antibodies, against a broad range of variant antigens, are important for protection against febrile malaria episodes in children who are in the process of acquiring malaria immunity [13]. Severe disease is therefore rare during the first few months of life [16].

The use of intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy (IPTp) has been shown to increase birth weight and reduce the incidence of LBW [34] as well as reduce pregnancy-related parasitaemia and anaemia [35,36,37,38,39,40]. Regardless of these benefits, there is concern that “any exposure-reducing interventions could result in the loss of or failure to acquire protective (PAM) immunity” [41,42,43] which would increase the overall, long-term disease burden [44] by increasing morbidity and mortality [45, 46]. The use of IPTp with Sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine (SP) treatment of primigravidae has also been shown to reduce levels of plasma IgG, which protects against pregnancy-associated falciparum malaria [47, 48] and severe malaria among children [49]. However, the extent to which IPTp may interfere with acquisition of protective immunity against PAM is largely undefined, particularly in Ghana. The present study was designed to evaluate the effect of IPTp on antibody-mediated immunity against malaria during pregnancy. This study further sought to determine whether IPTp disrupts the transfer of maternal antibodies across the placenta. Specific concentrations of IgG and immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibodies against a glutamate-rich protein (GLURP) and crude antigen (Ag) preparation were obtained from pregnant women from enrolment to delivery and from cord blood of the infants.

Methods

Study setting

The study was conducted at the Alpha Medical Hospital in Madina, a densely populated and fast-growing, peri-urban area in the Ga-East Municipality of Accra, southern Ghana. This study was a sub-component of a larger study that looked at IPTp implementation in the Ga-East Municipality of Accra. The full details of the study setting and characteristics of the participants are described in Stephens et al. [50].

Study participants

The study participants were selected from all pregnant women making their first visit for antenatal care at the Alpha Medical Centre from July to August regardless of ethnic or socio-economic background, gestation, parity or gravid status. The inclusion criteria were pregnant women who indicated their intention to deliver at the facility and who had not previously taken IPTp for their current pregnancy.

Study procedure

Briefly, pregnant women who met the inclusion criteria were invited to volunteer to participate in the study. Socio-demographic information was collected by questionnaire, as well as information on gravidity, parity, the use of IPTp, insecticidal-treated nets (ITNs), drug seeking behaviour, and other anti-malarial practices during pregnancy. Gestation was estimated from abdominal examination by qualified midwives and confirmed later by scan. A venous blood sample was obtained at first registration for general screening and for plasma analysis to determine pre-IPTp antibody status. Women who were eligible for IPTp administration were served by hospital staff at monthly intervals. Blood samples were then obtained 4 weeks after each IPTp administration to determine their post-IPTp P. falciparum antibody titre. Placenta and cord blood samples were also collected at delivery. Infants born to these women were followed at monthly intervals for 6 months. The body temperature of the infants was determined at each visit. Follow-up was facilitated by the use of mobile phones.

Blood sampling

Venous blood was collected into 5-ml K3EDTA vacutainer tubes with butterfly needles (Becton–Dickinson Vacutainer Systems, UK) by a qualified phlebotomist. Each tube was labelled with the subject’s unique identification number and stored in a cool box. Samples were transferred to the laboratory at the University of Ghana, Legon for further analysis. Whole blood samples were centrifuged at 2000 revolutions per minute (rpm) using a Spectrafuge (Labnet International, Inc, Edison, NJ, USA) and the plasma was carefully collected and stored at −40 °C for anti-malaria antibody assays. The resulting pellet of red cells were washed twice and then cryopreserved in glycerolyte solution at −40 °C.

Maternal intervillous blood (IVB) was obtained at delivery by a modified placental prick method as described by Othoro et al. [51]. An experienced technician accessed the placental intervillous spaces through the chorionic plate after delivery. The placenta was carefully placed on a raised sterile wire mesh stand, with the chorionic plate facing downward to facilitate blood accumulation and IVB space. A large-bore, 14-gauge needle attached to a syringe was directed approximately 0.5 cm deep through the wire mesh into the intervillous space, denoted as dark purple regions, taking care to avoid puncturing the surrounding fetal vessels on the surface of the chorionic plate. The syringe was gently pulled to create a vacuum and initiate blood flow. The needle was withdrawn to collect a 5-ml sample into a previously labelled micro centrifuge tube charged with 25 μl of a 1:4 heparin (stock concentration, 1000 units/ml) dilution in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The procedure was repeated to collect cord blood. The samples were stored in a refrigerator at the maternity unit and transferred in a cool box to the laboratory for further processing. Birth weight of each infant was recorded by the delivering midwife.

Antibody analysis

Antibodies against two antigens, a specific blood-stage antigen of P. falciparum or GLURP, and a soluble crude antigen preparation from whole blood-stage parasites were determined as previously described [52]. Briefly, 96-well micro titre plates (Immulon 2 HBX) were coated (100 μl/well) at 1 μg/ml for GLURP and 5 × 105 cells/well for crude antigen in plain PBS. The plates were incubated overnight at 4 °C, retrieved, washed four times with PBS/Tween 20, then incubated with 200 μl/well of blocking buffer (3% skimmed milk in 1X PBS) for 1 h at room temperature in a humidified chamber. The plates were washed as described and 100 ul of plasma pre-diluted at 1:2000 in 1% PBS/milk was added in duplicates to each well and incubated for 2 h as described. To control for inter-assay variations in the procedure, each assay plate included a pool of hyper immune plasma known to be positive for total IgG to GLURP and the schizont extract, diluted at 1:500. To the plates were then added 100 μl/well of 0.5 μg/ml peroxidase labelled goat anti-human IgG (H + L) conjugate (KPL), and peroxidase-labelled goat anti-human IgM at 0.5 μg/ml for 1 h at room temperature for the IgG and IgM respectively and incubated for 1 h. Plates were developed with 100 μl/well 3,3′ 5,5′ tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate for 30 min in the dark. After incubation the reaction was stopped with 100 μl 0.2 M H2SO4 and optical density (OD) was read at 450 um with a reference wavelength of 630 um using a spectrophotometer (Vmax Kinetic micro plate reader-Molecular Devices Corporation, CA, USA). Optical density values were converted to concentrations using a 4-parameter curve fit using pure human IgG and IgM standards fitted on each plate.

Ethical considerations

Ethical clearance for the study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Noguchi Memorial Institute for Medical Research, College of Health Sciences, University of Ghana, Legon (Study Number: 004/06-07). An informed consent was obtained from each volunteer and assent was documented by signing or by thumb printing the consent form.

Statistical analysis

Responses to the questionnaire were numerically coded on paper and later transferred into an electronic database. Responses and laboratory results were entered into a computer in Epi Info version 3.5. The data were then cleaned and verified. Data summaries (frequencies and distributions) were examined. Participants were grouped by gravidity and by gestation at registration. The mean values for various parameters, such as antibody levels, use of bed nets and the number of IPTp doses administered for various categories of pregnant women, were compared using standard parametric and non-parametric statistical methods using the SPSS and EPI info statistical software.

For normally distributed data, comparisons between means and percentages were done by Students’ t test, ANOVA and Fisher’s exact tests as appropriate at P < 0.05 significant level. Multivariate regression was performed with the number of IPTp doses taken and antibody titre against age, parity and gestation.

Limitations

Some limitations are acknowledged. First, HIV status is important in antibody reduction but data were not collected and therefore were not investigated in the present study. Second, it was not possible to examine the association between malaria antibody levels and bed nets due to the low usage of ITNs. Third, although malaria transmission is seasonal with a peak during the rainy season (July to September), the very low prevalence of malaria, reported in an earlier study [50] among the pregnant women, limited the ability to assess seasonality effects.

Results

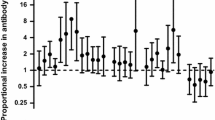

A total of 320 pregnant women were enrolled in the study. The details of the characteristics of the study participants have been reported in [50]. In brief, the mean gestation at registration and onset of IPTp uptake were 18.5 and 23.5 weeks, respectively. Peripheral blood parasitaemia and placental positivity were 5 and 2.5%, respectively. There were 37.8% (121/320) deliveries in the hospital. One-hundred-and-twenty-one paired placenta and cord blood was obtained at delivery. The rest of the women either did not deliver in the hospital as they had indicated and a few were missed at the time of delivery. The mean concentrations of antibodies against IgG and IgM are shown in Figs. 1 and 2, respectively.

The mean concentrations of IgG against GLURP decreased from the baseline to post IPT1 and slightly increased after IPT2, dropped after IPT3 and plateaued, but imposition of trend lines showed a sharp decrease in trend from baseline to delivery. IgG antibodies against the crude malaria parasite Ag was lower than IgG against GLURP at baseline (pre-IPTp) but increased after the first dose of IPT (IPT1) and then declined until after IPT2 and then decreased at delivery (placental blood) (Fig. 1). The trend lines showed a general decrease. The mean antibody concentrations of IgG against crude Ag were significantly higher than the corresponding concentration of anti-GLURP IgG throughout pregnancy, except at baseline (P < 0.01).

The mean concentrations of anti-GLURP IgM antibodies were higher than those of the anti-crude IgM antibodies at baseline and after IPT1 but the levels reversed after IPT2 and after IPT3 and again at delivery. The levels of IgM antibodies against both Crude Ag increased then decreased after IPT3 but the general trend showed a decrease in both. IgM GLURP also showed a general decrease from post-IPTp1 (Fig. 2). Concentrations of anti-GLURP IgM antibodies were significantly higher than concentration of anti-crude IgM antibodies at baseline but reversed at delivery (P = 0.01).

The concentrations by parity are shown in Figs. 3, 4, 5 and 6. Analysis of the differences between the mean plasma concentrations of antibodies (IgG and IgM) against the two malaria parasite antigens in primigravidae and multigravidae showed no significant differences. There were significant differences for the mean antibody values of both IgM crude and IgM GLURP (P = 0.01) but no significant differences between IgG crude and IgG GLURP (P = 0.195). Majority 96.7% (117/121) of the babies delivered weighed at least 2.5 kg. Of the few women 3.3% (4/121) who delivered babies with birth weight less than 2.5 kg, two had taken one dose and the other two had taken two doses of IPT. The data showed that one of them was a primigravida, two were multigravidae and the gravid status of the fourth person was unknown. Among those who delivered babies of at least 2.5 kg, 7.7% (9/117) had not received any IPT during pregnancy, while 46.2% (54/117) received the three doses of IPT, which was the maximum number of recommended doses at the time of the study. A significant correlation was found between the number of IPTp doses taken and the weight of the baby at delivery (P = 0.024). There was also a strong positive correlation between antibody levels of placental blood and cord blood.

Anti-GLURP IgG levels declined from baseline to delivery for the primigravida while mean concentrations among the multigravida declined at baseline but the level increased after IPTp2 and then decreased after IPTp3 (Fig. 3). Both anti-GLURP IgG and IgM concentrations for the multigravida were higher than those for the primigavida except at IPTp3 where the levels for the multigravida dropped remarkably (Figs. 3, 4).

Discussion

In the present study, GLURP was used as pure antigen together with a crude antigen preparation containing many antigens. Generally, although the IgG antibody levels against the crude P. falciparum antigen were found to be significantly higher than those against GLURP, both have been found to correlate with protection against malaria [53, 54]. The concentrations of both antibodies showed a decline with IPTp uptake probably as a result of decay in antibodies or as a result of the clearance of parasitaemia by treatment with SP. This is consistent with other studies [43, 48, 55, 56], which also found a decline in the levels of antibodies against several antigens during pregnancy and after delivery. The decrease in antibody levels is believed to be linked with pregnancy-specific malaria immunity rather than to non-pregnancy associated malaria antigens [48] as speculated elsewhere [50] or possibly to short-lived responses in the absence of infection [43, 55].

HIV-infected pregnant women are known to also exhibit low levels of antibodies to P. falciparum antigens [57, 58] but this study did not collect information on HIV status of the study participants and therefore was unable to find any linkage for the low levels of IgG among the study participants. Again, previous malaria episodes have been demonstrated to be associated with increased antibody levels [59] but this was not explored in the present study. Another interesting factor associated with failure to acquire protective PAM immunity is exposure-reducing interventions [41]. Exposure to ITN interventions either early or later in pregnancy have also been shown to reduce malaria immunity but ITN usage among the study participants was very low (5%) as reported in an earlier study [50]. Analysis of the effect of the ITN use on the antibody levels could not be done due to the low numbers. Antibody levels could also be affected by seasonal change [60] or any particular pregnancy [61, 62] but there was a general decline among the pregnant women who were recruited at the beginning of the study and those recruited later as the recruitment period was short (July to August) and there was minimum or no variation in the season.

Although there were differences expected in parity of the women, both primigravidae and multigravidae showed a decline in antibody levels in support of the low prevalence rate. Another factor of interest is the plasma volume expansion associated with pregnancy, which might contribute to the overall decrease in antibody levels, attributed to low or lack of exposure [56]. A virtual anaemia is caused by an increase in circulating blood plasma. As a result, there are fewer red blood cells per ml of plasma compared to the blood of the non-pregnant, thereby making the blood of the pregnant woman more diluted and less concentrated in antibodies. Until recently this physiological phenomenon has been taken to mean that the pregnant woman is anaemic and therefore mean corpuscular volume (MCV) is a more accurate measure of anaemia. Nevertheless, a comparison with the above studies shows low anaemia rates for the women in the present study population [50]. This is supported by reports of a study in a rural district in Ghana with anaemia prevalence rate of 57.1% (haemoglobin (Hb) <10 g/dl) among pregnant women. The study concluded that anaemia was more prevalent among rural pregnant women than those in the urban areas of the same district (P = 0.01) [29].

The low prevalence of moderate and severe anaemia is supported by the finding of low prevalence of peripheral blood parasitaemia. Contrary to earlier studies, malaria among pregnant women living in areas of malaria has been reported to be symptomatic [5, 63]. Another study in an area of high and intense malaria transmission has shown the overall prevalence of malaria among women attending ANC to be about 47% with anaemia rate of 72% (Hb < 11 g/dl) and severe anaemia rate of 2% (Hb < 7 g/dl) [64]. This still underscores the fact that malaria remains the major cause of maternal anaemia in Madina and therefore programmes and policies aimed at the control of anaemia in pregnant women in Madina should focus primarily on malaria.

The peaks of IgM and IgG antibody levels post-IPT1, also around the second trimester, may indicate increased susceptibility to malaria, which usually occurs in the second trimester [28, 65]. The presence of IgM suggests that the women were still infected despite the IPTp they were receiving during pregnancy or that the parasites were possibly resistant to SP to some degree [66]. However, SP-IPTp has recently been shown to clear parasitaemia in asymptomatic women [67]. The steady decline in anti-IgM against both crude antigen and GLURP from baseline and after each dose of IPTp towards delivery may reflect the lower exposure to malaria, since infection and intra-erythrocytic replication of parasites is required for the induction of these antibodies. This shows that any methods which either reduce exposure to mosquito bites, such as bed nets or interrupts erythrocytic replication of the parasites, such as anti-malarials, can effectively reduce antibody levels against blood-stage antigens as shown by the present study. The decline in IgG levels shown in this study has also been reported [47] and may reflect the use of IPTp. However, since the threshold for protection of these antibodies against malaria were not established in the present study it is impossible to determine whether these women were rendered susceptible to malaria as a result of IPTp use.

The lower levels of anti-crude IgM antibodies in multigravidae as compared to primigravidae, reflects possible sub-microscopic parasitaemia carriage in primigravidae. This reflects new infections which could mean that most of the primigravidae might have experienced current infections compared to multigravidae, which is inconcert with the literature.

IgG against the crude antigen and GLURP were present in both placenta and cord blood even though the mean concentrations in cord blood were less than in the placenta, as found in other studies [68, 69]. A possible explanation is that in women with placental malaria, the anti-malarial antibodies bind to malaria antigen and become trapped in the placenta as immune complexes [70]. Further, the lower antibody levels in cord blood may be due to the thickening of the placental membranes as a result of malaria infection [71], a condition which may serve as a barrier to the efficient transfer of maternal proteins in a more generalized manner and which is similar to what happens with the transfer of low levels of anti-tetanus antibodies by women with placental malaria [72]. However, in the present study peripheral blood parasitaemia was only 5%, while placental malaria was present in samples examined (2.5%) [50]. Future studies should include other non-malarial antigens, including measles antigen, to provide better understanding of trans-placental transfer of maternal antibody.

There are presently no specific quantities of malaria antibodies that correlate with clinical protection [73] and therefore it is not possible to state whether or not the antibody concentrations in the cord blood were enough to offer protection to the infants born to study participants. Children with particularly high levels of antibodies at birth can remain antibody positive (in the absence of active immunization by infection) up to 11 months but in Ghana the median duration of maternal antibodies to a crude P. falciparum schizont extract was 14 weeks [74]. Maternal antibody falls to minimal levels by the 4th month of life while infant antibody titres began to rise from about 6 months of age, following active immunization by exposure [75]. Newborn infants in endemic areas are markedly resistant to falciparum malaria due to high levels of anti-malarial IgG passively transferred across the placenta. Consequently, severe disease is rare during the first few months of life, and infections tend to be low density and relatively asymptomatic during this period. However, congenital parasitaemia may present 2–3 months after delivery when maternal antibodies wear off [16].

There are conflicting views about the protection conferred on infants by maternal antibodies with the majority of the studies concluding that despite the small numbers in their respective studies, maternal antibodies do protect infants from clinical malaria and high parasitaemia irrespective of the presence or absence of maternally derived antibody, but do not protect infants from malaria infection, most of whom are asymptomatic [76]. There is also evidence for an association between decreasing levels of maternally derived, malaria-specific IgG and increasing risk of clinical malaria at a population level, but the numbers of children in most of the studies were not large enough to provide any convincing analysis [71]. The small numbers of children born to the study is a challenge. Women gave their consent to participate in the study and were recruited based upon their delivery at the hospital. However, socio-cultural practices made about 60% of them deliver outside the study-designated facility. They could not be replaced because the study was time bound. The study also provided a delivery package as incentive and participants received priority consultation at the ANC.

None of the children in the present study registered hyperpyrexia (body temperature >36.5 °C) during the post-natal follow-up to justify the collection of blood samples as per the approved protocol. There are many reasons attributed to protection in childhood. These range from the biting habits of anopheline mosquitoes that have preference to for blood of adults and older children, to protection by breast milk constituents. Others are the physiologic barrier by foetal haemoglobin (HbF), resulting in the delay of parasite development and protection from severe illness [32]. The introduction of IPTp has recently been shown to be associated with increased risk of severe malaria among infants [45]. This has serious implications for the use IPTp and raises questions about the passive transfer of antibodies across the placenta as well as the quality and quantities transferred.

Conclusions

The study concludes that intermittent preventive treatment reduces immunoglobulin G levels among pregnant women on IPTp due to the low prevalence of parasitaemia. The children born to the mothers were protected for 6 months and showed no clinical symptoms after follow-up and thus IPTp allowed the transfer of antibodies across the placenta. Future studies should look into other non-malarial antigens to provide better understanding of antibody transfer.

Abbreviations

- AG:

-

Antigen

- ANC:

-

Antenatal clinic

- CSA:

-

chondroitin sulfate–A

- DOT:

-

direct observed therapy

- GLURP:

-

glutamate-rich protei

- IG:

-

immunoglobulin

- IPTp:

-

intermittent preventive treatment in pregnancy

- IVB:

-

intervillous blood

- LBW:

-

low birth weight

- MCV:

-

mean corpuscular volume

- OD:

-

optical density

- PAM:

-

pregnancy-associated malaria

- PBS:

-

phosphate buffer saline

- SP:

-

Sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine

- VSA:

-

variant surface antigen

References

WHO. Global malaria programme: pregnant women and infants. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. http://apps.who.int/malaria/pregnantwomenandinfants.html. Accessed Dec 2016.

Desai M, ter Kuile FO, Nosten F, McGready R, Asamoa K, Brabin B, et al. Epidemiology and burden of malaria in pregnancy. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7:93–104.

Monif GRG, Baker DA. Infectious disease in obstetrics and gynecology. 6th ed. New York: Parthenon; 2004. p. 280–6.

WHO. A strategic framework for malaria prevention and control during pregnancy in the African Region. Brazzaville: World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa; 2004. (AFR/MAL/04/01).

Ofori MF, Dodoo D, Staalsoe T, Kurtzhals JA, Koram K, Theander TG, et al. Malaria-induced acquisition of antibodies to Plasmodium falciparum variant surface antigens. Infect Immun. 2002;70:2982–8.

Roberts DJ. Understanding the naturally acquired immunity to Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Infect Immun. 2003;71:589–90.

Bull PC, Lowe BS, Kortok MCS, Newbold CI, Marsh K. Parasite antigens on the infected red cell are targets for naturally acquired immunity to malaria. Nat Med. 1998;4:358–60.

Giha HA, Staalsoe T, Dodoo D, Roper C, Satti GM, Arnot DE, et al. Antibodies to variable Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocyte surface antigens are associated with protection from novel malaria infections. Immunol Lett. 2000;71:117–26.

Marsh K, Otoo L, Hayes RJ, Carson DC, Greenwood BM. Antibodies to blood stage antigens of Plasmodium falciparum in rural Gambians and their relation to protection against infection. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1989;83:293–303.

Mackintosh CL, Mwangi T, Kinyanjui SM, Mosobo M, Pinches R, Williams TN, et al. Failure to respond to the surface of Plasmodium falciparum infected erythrocytes predicts susceptibility to clinical malaria amongst African children. Int J Parasitol. 2008;38:1445–54.

Richards JS, Beeson JG. The future for blood-stage vaccines against malaria. Immunol Cell Biol. 2009;87:377–90.

Marsh K, Kinyanjui S. Immune effector mechanisms in malaria. Parasite Immunol. 2006;28(Suppl 1–2):51–60.

Dodoo D, Staalsoe T, Giha H, Kurtzhals JA, Akanmori BD, Koram K, et al. Antibodies to variant antigens on the surfaces of infected erythrocytes are associated with protection from malaria in Ghanaian children. Infect Immun. 2001;69:3713–8.

Riley EM, Allen SJ, Wheeler JG, Blackman MJ, Bennett S, Takacs B, et al. Naturally acquired cellular and humoral immune responses to the major merozoite surface antigen (Pf MSP1) of Plasmodium falciparum are associated with reduced malaria morbidity. Parasite Immunol. 2007;14:321–37.

Andrews KT, Lanzer M. Maternal malaria. Plasmodium falciparum sequestration in the placenta. Parasitol Res. 2002;88:715–23.

Schantz-Dunn J, Nour NM. Malaria and pregnancy. A global health perspective. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2009;2:186–92.

Beeson JG, Amin N, Kanjala M, Rogerson SJ. Selective accumulation of mature asexual stages of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes in the placenta. Infect Immun. 2002;70:5412–5.

Fried M, Duffy PE. Adherence of Plasmodium falciparum to chondroitin sulfate A in the human placenta. Science. 1996;272:1502–4.

Sharling L, Enevold A, Sowa KMP, Staalsoe T, Arnot DE. Antibodies from malaria-exposed pregnant women recognize trypsin resistant epitopes on the surface of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes selected for adhesion to chondroitin sulphate A. Malar J. 2004;3:31.

Fievet N, Le Hesran JY, Cottrell G, Doucoure S, Diouf I, N’diaye JL, et al. Acquisition of antibodies to variant antigens on the surface of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes during pregnancy. Infect Genet Evol. 2006;6:459–63.

Ricke CH, Staalsoe T, Koram K, Akanmori BD, Riley EM, Theander TG, et al. Plasma antibodies from malaria-exposed pregnant women recognize variant surface antigens on Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes in a parity-dependent manner and block parasite adhesion to chondroitin sulfate A. J Immunol. 2000;165:3309–16.

Steketee RW, Nahlen BL, Parise ME, Menendez C. The burden of malaria in pregnancy in malaria-endemic areas. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2001;64(Suppl 1):28–35.

Guyatt HL, Snow RW. Impact of malaria during pregnancy on low birth weight in sub-Saharan Africa. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17:760–9.

Menendez C. The impact of placental malaria on gestational age and birthweight. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:1740–5.

McCormick MC. The contribution of low birth weight to infant mortality and childhood morbidity. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:82–90.

Bloland P, Slutsker L, Steketee RW, Wirima JJ, Heymann DL, Breman JG. Rates and risk factors for mortality during the first two years of life in rural Malawi. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1996;55(Suppl 1):82–6.

Le Hesran JY, Cot M, Personne P, Fievet N, Dubois B, Beyeme M, et al. Maternal placental infection with Plasmodium falciparum and malaria morbidity during the first 2 years of life. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;146:826–31.

Brabin BJ. An analysis of malaria in pregnancy in Africa. Bull World Health Organ. 1983;61:1005–16.

Glover-Amengor M, Owusu WB, Akanmori BD. Determinants of anaemia in pregnancy in Sekyere west district, Ghana. Ghana Med J. 2005;39:102–7.

Ofori MF, Ansah E, Agyepong I, Ofori-Adjei D, Hviid L, Akanmori BD. Pregnancy-associated malaria in a rural community of Ghana. Ghana Med J. 2009;43:13–8.

Marsh K. Immunology of human malaria. In: Bruce Chwatt’s Essential malariology. 3rd edition. Edward Arnold, Hodder and Stoughton Ltd., Mill Road, Dunton Green, Sevenoaks Kent TN13 2YA. 1993.

Dobbs KR, Dent AE. Plasmodium malaria and antimalarial antibodies in the first year of life. Parasitology. 2016;143:129–38.

Hviid L, Staalsoe T. Malaria immunity in infants: a special case of a general phenomenon? Trends Parasitol. 2004;20:66–72.

Fawole B. Interventions to prevent malaria-related morbidity and mortality in pregnancy: RHL commentary. Geneva: WHO Reproductive Health Library, World Health Organization; 2009.

Ouédraogo S, Koura GK, Bodeau-Livinec F, Accrombessi MM, Massougbodji A, Cot M. Maternal anemia in pregnancy: assessing the effect of routine preventive measures in a malaria-endemic area. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;88:292–300.

Menendez C, Bardaji A, Sigauque B, Romagosa C, Sanz S, Serra-Casas E, et al. A randomized placebo-controlled trial of intermittent preventive treatment in pregnant women in the context of insecticide treated nets delivered through the antenatal clinic. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1934.

Kayentao K, Kodio M, Newman RD, Maiga H, Doumtabe D, Ongoiba A, et al. Comparison of intermittent preventive treatment with chemoprophylaxis for the prevention of malaria during pregnancy in Mali. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:109–16.

Tukur IU, Thacher TD, Sagay AS, Madaki JK. A comparison of Sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine with chloroquine and pyrimethamine for prevention of malaria in pregnant Nigerian women. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;76:1019–23.

ter Kuile FO, van Eijk AM, Filler SJ. Effect of Sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine resistance on the efficacy of intermittent preventive therapy for malaria control during pregnancy: a systematic review. JAMA. 2007;297:2603–16.

Feng G, Simpson JA, Chaluluka E, Molyneux ME, Rogerson SJ. Decreasing burden of malaria in pregnancy in Malawian women and its relationship to use of intermittent preventive therapy or bed nets. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e12012.

Ghani AC, Sutherland CJ, Riley EM, Drakeley CJ, Griffin JT, Gosling RD, et al. Loss of population levels of immunity to malaria as a result of exposure-reducing interventions: consequences for interpretation of disease trends. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e4383.

Aitken EH, Mbewe B, Luntamo M, Kulmala T, Beeson JG, Ashorn P, et al. Antibody to P. falciparum in pregnancy varies with intermittent preventive treatment regime and bed net use. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e29874.

Teo A, Hasang W, Randall LM, Unger HW, Siba PM, Mueller I, Brown GV, Rogerson SJ. Malaria preventive therapy in pregnancy and its potential impact on immunity to malaria in an area of declining transmission. Malar J. 2015;14:215.

Askjaer N, Maxwell C, Chambo W, Staalsoe T, Nielsen M, Hviid L, et al. Insecticide-treated bed nets reduce plasma antibody levels and limit the repertoire of antibodies to Plasmodium falciparum variant surface antigens. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2001;8:1289–91.

Snow RW, Marsh K. The consequences of reducing transmission of Plasmodium falciparum in Africa. Adv Parasitol. 2002;52:235–64.

Reyburn H, Mbatia R, Drakeley C, Bruce J, Carneiro I, Olomi R, et al. Association of transmission intensity and age with clinical manifestations and case fatality of severe Plasmodium falciparum malaria. JAMA. 2005;293:1461–70.

Staalsoe T, Shulman CE, Dorman EK, Kawuondo K, Marsh K, Hviid L. Intermittent preventive Sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine treatment of primigravidae reduces levels of plasma immunoglobulin G, which protects against pregnancy-associated Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Infect Immun. 2004;72:5027–30.

Teo A, Hasang W, Randall LM, Feng G, Bell L, Unger H, et al. Decreasing malaria prevalence and its potential consequences for immunity in pregnant women. J Infect Dis. 2014;210:1444–55.

Harrington WE, Morrison R, Fried M, Duffy PE. Intermittent preventive treatment in pregnant women is associated with increased risk of severe malaria in their offspring. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e56183.

Stephens JK, Ofori MF, Quakyi IA, Wilson ML, Akanmori BD. Prevalence of peripheral blood parasitaemia, anaemia and low birthweight among pregnant women in a suburban area in coastal Ghana. Pan Afr Med J. 2014;17(Suppl. 1):3.

Othoro C, Moore JM, Wannemuehler K, Nahlen BL, Otieno J, Slutsker L, et al. Evaluation of various methods of maternal placental blood collection for immunology studies. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2006;13:568–74.

Dodoo D, Theander TG, Kurtzhals JAL, Koram K, Riley E, Akanmori BD, et al. Levels of antibody to conserved parts of Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein 1 in Ghanaian children are not associated with protection from clinical malaria. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2131–7.

Bull PC, Lowe BS, Kortok M, Marsh K. Antibody recognition of Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte surface antigens in Kenya: evidence for rare and prevalent variants. Infect Immun. 1999;67:733–9.

Bull PC, Marsh K. The role of antibodies to Plasmodium falciparum-infected-erythrocyte surface antigens in naturally acquired immunity to malaria. Trends Microbiol. 2002;10:55–8.

Ampomah P, Stevenson L, Ofori MF, Barfod L, Hviid L. Kinetics of B cell responses to Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 in Ghanaian women naturally exposed to malaria parasites. J Immunol. 2014;192:5236–44.

Ndam NT, Denoeud-Ndam L, Doritchamou J, Viwami F, Salanti A, Nielsen MA, et al. Protective antibodies against placental malaria and poor outcomes during pregnancy, Benin. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21:813–23.

Mount AM, Mwapasa V, Elliott SR, Beeson JG, Tadesse E, Lema VM, et al. Impairment of humoral immunity to Plasmodium falciparum malaria in pregnancy by HIV infection. Lancet. 2004;363:1860–7.

Vandemoortele M, Bird K. Improved economic conditions in Malawi: progress from a low base. http://www.odi.org.uk/publications/5480-malawi-economic-conditions-poverty-development-progress. Accessed 20 Apr 2017.

Mayor A, Kumar U, Bardají A, Gupta P, Jiménez A, Hamad A, et al. Improved pregnancy outcomes in women exposed to malaria with high antibody levels against Plasmodium falciparum. J Infect Dis. 2013;207:1664–74.

Crompton PD, Kayala MA, Traore B, Kayentao K, Ongoiba A, Weiss GE, et al. A prospective analysis of the Ab response to Plasmodium falciparum before and after a malaria season by protein microarray. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:6958–63.

Fowkes FJ, McGready R, Cross NJ, Hommel M, Simpson JA, Elliott SR, et al. New insights into acquisition, boosting, and longevity of immunity to malaria in pregnant women. J Infect Dis. 2012;206:1612–21.

Aitken EH, Mbewe B, Luntamo M, Maleta K, Kulmala T, Friso MJ, et al. Antibodies to chondroitin sulfate A-binding infected erythrocytes: dynamics and protection during pregnancy in women receiving intermittent preventive treatment. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:1316–25.

Tagbor H, Bruce J, Browne E, Greenwood B, Chandramohan D. Malaria in pregnancy in an area of stable and intense transmission: is it asymptomatic? Trop Med Int Health. 2008;13:1016–21.

Clerk CA, Bruce J, Greenwood B, Chandramohan D. The epidemiology of malaria among pregnant women attending antenatal clinics in an area with intense and highly seasonal malaria transmission in northern Ghana. Trop Med Int Health. 2009;14:688–95.

Kalilani L, Mofolo I, Chaponda M, Rogerson SJ, Meshnick SR. The effect of timing and frequency of Plasmodium falciparum infection during pregnancy on the risk of low birth weight and maternal anaemia. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2010;104:416–22.

Mbugi EV, Mutayoba BM, Malisa AL, Balthazary ST, Nyambo TB, Mshinda H. Drug resistance to Sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine in Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Mlimba, Tanzania. Malar J. 2006;5:94.

Coulibaly SO, Kayentao K, Taylor S, Guirou EA, Khairallah C, Guindo N, et al. Parasite clearance following treatment with Sulphadoxine–pyrimethamine for intermittent preventive treatment in Burkina-Faso and Mali: 42-day in vivo follow-up study. Malar J. 2014;13:41.

Campbell CC, Martinez JM, Collins WE. Seroepidemiological studies of malaria in pregnant women and newborns from coastal El Salvador. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1980;29:151–7.

Mutabingwa TK, Malle LN, Verhave JP, Eling WMC, Meuwissen JHET, de Geus A. Malaria chemosuppression during pregnancy IV. Its effect on the newborn’s passive malaria immunity. Trop Geogr Med. 1993;45:150–6.

Maeno Y, Steketee RW, Nagatake T, Tegoshi T, Desowitz RS, Wirima JJ, et al. Immunoglobulin complex deposits in Plasmodium falciparum-infected placentas from Malawi and Papua New Guinea. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1993;49:574–80.

Bulmer JN, Rasheed FN, Morrison L, Francis N, Greenwood BM. Placental malaria. II. A semi-quantitative investigation of the pathological features. Histopathology. 1993;22:219–25.

Brair ME, Brabin BJ, Milligan P, Maxwell S, Hart CA. Reduced transfer of tetanus antibodies with placental malaria. Lancet. 1994;343:208–9.

Akanmori BD, Afari EA, Sakatoku H, Nkrumah FK. A longitudinal study of malaria infection, morbidity and antibody titres in infants of a rural community in Ghana. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1995;89:560–1.

Riley EM, Wagner GE, Ofori MF, Wheeler JG, Akanmori BD, Tetteh K, et al. Lack of association between maternal antibody and protection of African infants from malaria infection. Infect Immun. 2000;68:5856–63.

Achidi EA, Perlmann H, Salimonu LS, Asuzu MC, Perlmann P, Berzins K. Antibodies to Pf155/RESA and circumsporozoite protein of Plasmodium falciparum in paired maternal-cord sera from Nigeria. Parasite Immunol. 1995;17:535–40.

Riley EM, Wagner GE, Akanmori BD, Koram KA. Do maternally acquired antibodies protect infants from malaria infection? Parasite Immunol. 2001;23:51–9.

Authors’ contributions

JKS conceived and designed the study and made substantial contribution to the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data, drafted the initial manuscript and revised it for intellectual content. MFO participated in the design of the immunoassay, assisted in the interpretation of the data and revised the manuscript critically for intellectual content. EK-B and EKD participated in the design of the immunoassay and analysis of the data. JKO participated in the immunoassay and contributed to the statistical analysis, MLW made substantial contribution to the design and interpretation of the data and revised the draft manuscript for intellectual content. IAQ contributed to the concept. BDA made substantial contribution the concept and design as well as analysis and interpretation of the data and also assisted in drafting the manuscript critically for intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

This research was mainly funded by the African Doctoral Dissertation Research Fellowship offered by the African Population and Health Research Centre (APHRC) in partnership with the International Development Research Centre (IDRC) and the University of Ghana College of Health Sciences Research Grant. The authors are grateful to the women who volunteered to participate in the study, and acknowledge the management and staff of the Alpha Medical Centre for their cooperation. The Head and staff of the Immunology Unit of the Noguchi Memorial Institute for Medical Research are acknowledged for providing bench space and technical support.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Stephens, J.K., Kyei-Baafour, E., Dickson, E.K. et al. Effect of IPTp on Plasmodium falciparum antibody levels among pregnant women and their babies in a sub-urban coastal area in Ghana. Malar J 16, 224 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-017-1857-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-017-1857-1