Abstract

Background

Pretreatment inflammatory factors, including neutrophil, lymphocyte, platelet and monocyte counts as well as the ratios between them such as neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet–lymphocyte ratio (PLR) and lymphocyte–monocyte ratio (LMR) have been suggested as potential prognostic predictors for patients with prostate cancer (PCa). However, the prognostic effects remain controversial. Therefore, the goal of this study was evaluate the prognostic values of these markers for PCa patients using a meta-analysis.

Methods

Potentially relevant publications in PubMed and Cochrane Library were searched. Pooled hazard ratio (HR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) for overall survival (OS), cancer-specific survival (CSS), progression-free survival (PFS), recurrence free survival (RFS) and distant metastases-free survival (DMFS) were determined using a fixed or random effects model by STATA 13.0 software.

Results

Thirty-two studies involving 21,949 participants were included. Our pooled results demonstrated that a high pretreatment NLR (HR = 1.55, 95% CI 1.37–1.76), PLR (HR = 1.72; 95% CI 1.36–2.18), neutrophil (HR = 1.10; 95% CI 1.03–1.18 and monocyte counts (HR = 2.25; 95% CI 1.67–3.05) predicted inferior OS, while elevated pretreatment LMR (HR = 2.27; 95% CI 1.76–2.94) was correlated with favorable OS. Furthermore, the higher NLR (HR = 1.62; 95% CI 1.29–2.04) and monocyte counts (HR = 1.75; 95% CI 1.36–2.25), but lower LMR predicted worse PFS (HR = 2.18; 95% CI 1.58–3.02); poor RFS was only associated with NLR (HR = 1.12; 95% CI 1.04–1.20). The subgroup analysis showed that the higher NLR may be a predictive factor for OS only in patients with mCRPC and undergoing chemotherapy; while the higher PLR was only significantly associated with OS in localized PCa regardless of treatment.

Conclusion

This meta-analysis reveals that pretreatment NLR, PLR, LMR, neutrophil, and monocyte counts may be effective predictive biomarkers for prognosis in patients with PCa.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Prostate cancer (PCa) represents a considerable health concern for the male population, with an estimated 161,360 new cases diagnosed and 26,730 death in 2017 in the United States [1]. Radical prostatectomy, androgen deprivation therapy, radiotherapy and chemotherapy have been recommended for treatment of patients with PCa, however, the overall survival (OS) rate remains unsatisfactory (5-year: 77.52%; 10-year: 62.57%) due to tumor local recurrence, progression or distal metastasis [2]. Therefore, how to stratify the high risk patients who will have poor prognosis because of non-response to the treatment strategies and prone to recurrence, progression or metastasis has become a hot issue urgently needed to be solved.

Conventionally, prognosis of patients with PCa can be predicted by pathologic tumor, node, metastasis (TNM) staging, prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level [3], PSA doubling time [3] and Gleason score [4]. Nevertheless, some clinical studies reported that patients with the same stage may have different prognoses [5] and prognosis seemed to be similar among patients with different PSA levels [6], indicating the insufficient accuracy of these factors for prognosis prediction. Thus, supplementary pretreatment biomarkers should be developed to assist clinicians to evaluate prognosis and further guide decision-making concerning therapeutic strategies.

Recently, accumulating evidences suggest inflammation may play important roles in the development and progression of PCa [7, 8]. Neutrophil, lymphocyte, platelet (PLT) and monocyte counts as well as the ratios between them such as neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet–lymphocyte ratio (PLR) and lymphocyte–monocyte ratio (LMR) are the common, indicators for the inflammatory status in patients with cancer [9,10,11]. Also, the collection of these indicators in blood is simple, noninvasive, and easily accessible. Hereby, circulating inflammatory factors may represent potential prognostic biomarkers for PCa in clinic. This hypothesis has been demonstrated by several studies: elevated NLR [12], PLR [13] and lower LMR [14] were found to be significantly associated with worse OS. However, a handful of studies demonstrated NLR and PLR may be ineffective markers for predicting PCa prognosis [15,16,17] or contrast conclusions were achieved (that is, higher NLR [18, 19] may be protective factors for prognosis). These controversial conclusions may be attributed to the different study design and small sample size. Thus, it is necessary to further evaluate the prognostic significance of the above inflammatory biomarkers for patients with PCa by performing a meta-analysis that can integrate all related articles. Compared with the recently published meta-analysis that included the articles up to July 2015 [20], February 2016 [21] for NLR and March 2017 for PLR [22], our study may collect more literatures by searching the relevant databases until August 2018, which may lead to more survival index predicted and a more convinced conclusion achieved. In addition, to our knowledge, there was no a pooled study to assess the prognostic significance of the neutrophil, lymphocyte, platelet and monocyte counts and LMR in PCa until now.

Given the newly emerging evidence, the goal of this study was to further conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis to reveal the prognostic performance (OS; PFS, progression-free survival; CSS, cancer-specific survival; DMFS, distant metastases-free survival; RFS, recurrence-free survival) of all well-known systemic inflammatory parameters for all patients with PCa and subgroups with different treatments. Pretreatment identification of the level or ratio of these biomarkers may be beneficial for the stratification of prognosis and schedule of medical treatments.

Materials and methods

Literature search strategy

This meta-analysis was performed in accordance to the Guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) [23, 24] (no review protocol existed previously).

A systematic literature search was carried out by using PubMed and Cochrane Library databases to assess the relationship between pretreatment systemic inflammatory biomarkers (NLR, PLR, LMR, platelet, lymphocyte, monocyte and neutrophil) and the prognosis of patients with PCa. The current search was updated to August 2018 using the combinations of the following keywords: (1) ‘NLR’ (or “neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio” or “neutrophil lymphocyte ratio” or “neutrophil-to-lymphocyte”); OR (2) ‘PLR’ (or “platelet to lymphocyte ratio” or “platelet lymphocyte ratio” or “platelet-to-lymphocyte”; OR (3) ‘LMR’ (or “lymphocyte monocyte ratio” or “lymphocyte-monocyte ratio” or “lymphocyte to monocyte ratio”); OR (4) ‘platelet’; OR (5) ‘lymphocyte’; OR (6) ‘monocyte’; OR (7) ‘neutrophil’; AND ‘prostatic cancer’ (or “prostate carcinoma” or “prostatic carcinoma”). Furthermore, the reference lists of all identified publications as well as pertinent reviews and meta-analyses were also manually inspected to further screen potentially eligible articles.

Selection criteria

Two investigators (HP and XGL) independently screened the candidate publications from the databases. Few disagreements were resolved by discussion and consensus. Literatures were considered eligible if they met the following inclusion criteria: (1) PCa was confirmed by pathological examination; (2) pretreatment (such as chemoradiotherapy, surgery) biomarkers (NLR, PLR, LMR, PLT, lymphocyte, monocyte and neutrophil) were measured by serum-based method and calculated by standard formula with same unit; (3) prognostic related outcomes [such as OS (all-cause mortality), PFS, CSS, DMFS and RFS] were investigated; (4) hazard ratio (HR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) could be directly obtained or indirectly calculated. Studies were excluded if they were: (1) duplicated literatures; (2) abstracts, letters, reviews, editorials, case reports, comments or non-clinical studies; (3) lack of insufficient data to estimate HR and 95% CI; and (4) literature written in language other than English.

Data extraction

Two investigators (HP and XGL) independently extracted the following data: name of first author, publication year, country, sampling time, sample size, study design, patient characteristics (including gender, age, patient status, duration of follow-up), treatment details, cut-off value, HR with 95% CI for survival and associated statistical methods. HR and 95% CI were extracted preferentially from multivariable analyses where available. If not, univariate analysis results were collected. Disagreements were resolved through discussion to reach consensus.

The quality of the included studies was assessed using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) [25] that consists of three domains: patients selection (0–4 points), comparability (0–2 points), and outcome assessment (0–3 points). Studies with the scores ≥ 7 were considered to be of high-quality.

Statistical analysis

Statistical heterogeneity among the studies was tested by using Cochrane’s Q (Chi squared) and I2 statistic [26]. A random-effects model was chosen to calculate the pooled HR and 95% CI for heterogeneous studies (Q test P value < 0.10 and I2 > 50%); otherwise, the fixed-effects model was used. Publication bias was assessed with Egger’s linear regression test with funnel plots [27]. The influence of publication bias on the overall effect was evaluated by the ‘‘trim and fill’’ method [28]. Sensitivity analysis was performed by recalculating the pooled HRs after omitting one study in each turn from the meta-analysis consecutively (leave-one-out procedure). In addition, a subgroup analysis was also performed according to stratification of ethnicity, sample size, study design, patient status, follow-up time, cut-off, statistical methods and therapy. All statistical analyses were conducted using the STATA software (version 13.0; STATA Corporation, College Station, TX, USA). P < 0.05 was set as the statistical significance level.

Results

Study characteristics

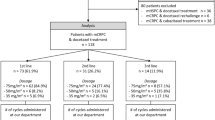

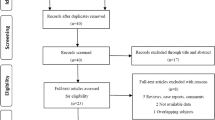

A flow chart of the literature search is presented in Fig. 1. The initial search yielded 4280 studies based on the search strategies, in which 1967 were excluded as they were duplicates. After title and abstract screening, 2231 studies were excluded because the following reasons: not PCa (n = 166), no prognosis information (n = 739), drug therapy effect assessment (n = 3), experience lecture (n = 31), review (n = 25), case (n = 30), animal studies (n = 539), cell studies (n = 395) and molecular studies (n = 303). Eighty-two full-text articles were then downloaded to assess their eligibility, in which 54 were further excluded because non-effective data could be collected (n = 47), NLR was detected postoperatively (n = 1) and NLR was combined with other to form a risk model (n = 1) and derived NLR (dNLR) was demined (n = 1). Ultimately, 32 studies (n = 21,949 participants) were included for subsequent meta-analysis [12,13,14,15,16, 18, 19, 29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52], of which 28 studies including 21,452 participants were included for NLR [12,13,14,15,16, 18, 19, 29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38, 40,41,42,43, 45,46,47, 50,51,52], 6 studies including 2994 participants for PLR [13, 17, 30, 37, 39, 44], 4 studies including 2594 participants for PLT [13, 30, 39, 48], 4 studies including 5133 participants for lymphocyte counts [30, 36, 39, 41], 3 studies including 4843 participants for neutrophil counts [30, 36, 41], 2 studies involving 504 participants for monocyte counts [14, 49] and 1 study involving 214 participants for LMR [14]. The study of Shigeta et al. [14] had two datasets (training and validation) and both of them were included for assessment of the prognostic value of NLR, LMR and monocyte for PCa. The other characteristics of the included studies are shown in Table 1. NOS scores of all of the selected articles were ≥ 7, suggesting high quality (Table 2).

Association between NLR and PCa survival

Twenty-five studies with 26 datasets evaluated the association between pretreatment NLR and OS in PCa patients. A significant heterogeneity was present among studies (I2 = 83.4%, P < 0.001) and thus a random-effects model was chosen to pool the study results. The synthesized estimates analysis showed that patients with elevated NLR had significantly shorter OS (HR = 1.55, 95% CI 1.37–1.76, P < 0.001) (Fig. 2a; Table 3).

Forest plots of the significant correlations of neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio with survival. a Overall survival; b progression-free survival; c recurrence-free survival. Squares are hazard ratio (HR); horizontal lines are 95% confidence intervals (CI); blue diamond indicates the pooled HR estimate with its 95% CI

There were 4 studies examined the relationship of pretreatment NLR with CSS in PCa patients. A significant heterogeneity was detected among studies (I2 = 61.5%, P = 0.05) and thus a random-effects model was applied. The estimated pooled HR (95% CI) of 1.14 (95% CI 0.89–1.45, P = 0.297) in 3 studies indicated that patients with an elevated NLR were not associated with shorter CSS after treatment (Table 3).

Eleven studies with 12 datasets analyzed the pretreatment NLR for predicting the PFS of PCa after treatment. A random-effects model was adopted to pool the study results because the I2 = 67.6% and P < 0.001. The pooled estimates analysis predicted PFS was significantly lower in PCa patients with an elevated NLR (random: HR = 1.62; 95% CI 1.29–2.04, P < 0.001) (Fig. 2b; Table 3).

There were 2 studies to investigate the relationship between pretreatment NLR and DMFS in PCa patients. The Cochran’s Q-test resulted in a P value < 0.001 and the corresponding I2 was 92.3%, indicating that there was significant heterogeneity among studies. A random-effects model analysis demonstrated no statistically significant difference in DMFS of patients with higher or lower NLR (HR = 1.81; 95% CI 0.55–6.01, P = 0.330; Table 3).

Six studies analyzed the relationship between pretreatment NLR and RFS in PCa patients. There was no evidence of heterogeneity among studies because the Cochran’s Q-test P-value was 0.560 and the corresponding I2 was 0%. A fixed-effects model analysis demonstrated the higher level of NLR indicated unfavorable RFS (HR = 1.12; 95% CI 1.04–1.20, P = 0.002) (Fig. 2c; Table 3).

Association between PLR and PCa survival

Six studies evaluated the association between pretreatment PLR and OS in PCa patients. No significant heterogeneity was present among studies (I2 = 0%, P = 0.575) and thus a fixed-effects model was chosen. The pooled analysis showed that higher level of PLR was associated with shorter OS (HR = 1.72; 95% CI 1.36–2.18, P < 0.001) (Fig. 3; Table 3).

There were 3 studies examined the relationship of pretreatment PLR with CSS in PCa patients. A significant heterogeneity was detected among studies (I2 = 78.7%, P = 0.009) and thus a random-effects model was applied. The estimated pooled HR (95% CI) of 1.56 (95% CI 0.82–2.97, P = 0.174) in 3 studies indicated that patients with an elevated PLR were not associated with shorter CSS after treatment (Table 3).

Association between LMR and PCa survival

One study with 2 datasets analyzed the pretreatment LMR for predicting the OS of PCa after treatment. No significant heterogeneity was present among studies (I2 = 27.8%, P = 0.239) and thus a fixed-effects model was chosen. The pooled analysis showed that higher level of LMR was associated with more favorable OS (HR = 2.27; 95% CI 1.76–2.94, P < 0.001) (Fig. 4a; Table 3).

One study with 2 datasets analyzed the pretreatment LMR for predicting the PFS of PCa after treatment. No significant heterogeneity was present among studies (I2 = 27.8%, P = 0.460) and thus a fixed-effects model was chosen. The pooled analysis showed that higher level of LMR was associated with longer PFS (HR = 2.18; 95% CI 1.58–3.02, P < 0.001) (Fig. 4b; Table 3).

Association between PLT and PCa survival

Three studies evaluated the association between pretreatment PLT and OS in PCa patients. There was evidence of heterogeneity among studies (I2 = 56.1%, P = 0.086) and thus a random-effects model was chosen. The pooled analysis showed that pretreatment PLT was not associated with OS (HR = 1.00; 95% CI 0.98–1.02, P = 0.910; Table 3).

Four studies evaluated the association between pretreatment PLT and CSS in PCa patients. There was no evidence of heterogeneity among studies (I2 = 15.4%, P = 0.315) and thus a fixed-effects model was chosen. The pooled analysis showed that pretreatment PLT was not associated with CSS (HR = 1.00; 95% CI 0.99–1.01, P = 0.850; Table 3).

Association between lymphocyte counts and PCa survival

Four articles studied the association between pretreatment lymphocyte counts and OS in PCa patients. There was no evidence of heterogeneity among studies (I2 = 0%, P = 0.710) and thus a fixed-effects model was chosen. The pooled analysis showed that pretreatment lymphocyte counts could not predict the OS (HR = 0.96; 95% CI 0.83–1.10, P = 0.529; Table 3).

Three articles provided CSS as the primary outcome. There was no evidence of heterogeneity among studies (I2 = 0%, P = 0.523) and thus a fixed-effects model was chosen. The pooled analysis showed that the higher lymphocyte counts also could not predict the CSS (HR = 0.85; 95% CI 0.66–1.09, P = 0.190; Table 3).

Two articles studied the association between pretreatment lymphocyte counts and RFS in PCa patients. There was no evidence of heterogeneity among studies (I2 = 0%, P = 0.824) and thus a fixed-effects model was chosen. The pooled analysis showed that pretreatment lymphocyte counts were similarly not associated with RFS (HR = 1.06; 95% CI 0.96–1.16, P = 0.260; Table 3).

Association between neutrophil counts and PCa survival

Three articles studied the association between pretreatment neutrophil counts and OS in PCa patients. There was no evidence of heterogeneity among studies (I2 = 0%, P = 0.604) and thus a fixed-effects model was chosen. The pooled analysis showed that patients with higher pretreatment neutrophil counts were expected to have shorter OS (HR = 1.10; 95% CI 1.03–1.18, P = 0.006) (Fig. 5; Table 3).

Two articles provided sufficient data on CSS outcome for the pooled estimate of neutrophil counts in PCa patients. There was no evidence of heterogeneity among studies (I2 = 0%, P = 0.771) and thus a fixed-effects model was chosen. The pooled analysis showed that the higher neutrophil counts did not predict poorer CSS (HR = 1.12; 95% CI 0.99–1.25, P = 0.065) (Table 3).

Two articles studied the association between pretreatment neutrophil counts and RFS in PCa patients. There was no evidence of heterogeneity among studies (I2 = 0%, P = 0.942) and thus a fixed-effects model was chosen. The pooled analysis showed no significant difference in neutrophil counts observed between patients with higher and lower pretreatment neutrophil counts (HR = 1.03; 95% CI 0.98–1.09, P = 0.188; Table 3).

Association between monocyte counts and PCa survival

Two articles with three datasets studied the association between pretreatment monocyte counts and OS in PCa patients. There was no evidence of heterogeneity among studies (I2 = 0%, P = 0.463) and thus a fixed-effects model was chosen. The pooled analysis showed that patients with higher pretreatment monocyte counts were expected to have shorter OS (HR = 2.25; 95% CI 1.67–3.05, P < 0.001) (Fig. 6a; Table 3).

Two articles with three datasets provided sufficient data on PFS outcome for the pooled estimate of monocyte counts in PCa patients. There was no evidence of heterogeneity among studies (I2 = 33.2%, P = 0.224) and thus a fixed-effects model was chosen. The pooled analysis showed that the higher monocyte counts predicted poorer PFS (HR = 1.75; 95% CI 1.36–2.25, P < 0.001) (Fig. 6b; Table 3).

Publication bias

The above analysis showed that NLR, PLR, neutrophil and monocyte counts were hematologic parameters significantly associated with prognosis (NLR: OS, PFS and RFS; PLR: OS; neutrophil counts: OS; monocyte counts: OS and PFS). Therefore, funnel plots of the pooled analysis of these 4 parameters were constructed to examine whether there was a publication bias. The results revealed that the publication bias was present in NLR for OS (P < 0.001) (Fig. 7a), but not in NLR for PFS (P = 0.189) and RFS (P = 0.398); PLR for OS (P = 0.218); neutrophil counts for OS (P = 0.454); monocyte counts for OS (P = 0.173) and PFS (P = 0.137). Subsequently, a trim-and-fill method was performed to explore the influence of publication bias on the effect estimate. The filled meta-analysis still indicated there was still a significant association between pretreatment NLR and OS (HR = 1.21; 95% CI 1.07–1.37, P = 0.007) (Fig. 7b). Only one study was included for LMR and thus publication bias was not present.

Sensitivity analyses

Sensitivity analysis was performed by assessing the potential impact of individual dataset on the pooled data. The results showed that pooled HR was not significantly altered when each single study was deleted every time (Fig. 8).

Subgroup analysis

The subgroup analyses according to ethnicity, sample size, study design, patient status, follow-up time, cut-off, statistical methods and therapy were only performed for NLR and PLR due to limited literatures. The results showed that elevated NLR predicted poor prognosis in almost all of stratified categories except localized PCa (HR = 1.10; 95% CI 0.93–1.31, P = 0.274), surgery (HR = 1.12; 95% CI 0.99–1.26, P = 0.072), radiotherapy (HR = 1.10; 95% CI 0.95–1.27, P = 0.198) for OS; and surgery (HR = 1.64; 95% CI 0.51–5.26, P = 0.404), prospective study design for PFS (HR = 1.42; 95% CI 0.89–2.26, P = 0.144) (Table 4). The high PLR also predicted poor OS in almost all of stratified categories except PCa (HR = 2.01; 95% CI 1.42–2.87, P = 0.068) and mCRPC (HR = 1.41; 95% CI 0.98–2.04, P = 0.068) (Table 5).

Discussion

Our present study, for the first time, included 32 studies to comprehensively evaluate the prognostic values of pretreatment systemic inflammatory factors (neutrophil, lymphocyte, platelet and monocyte counts as well as NRL, PLR and LMR) in patients with PCa. The results indicated that a high pretreatment NLR, PLR, neutrophil and monocyte counts predicted inferior OS outcomes; while elevated pretreatment LMR was correlated with favorable OS. In addition, the pooled data provided evidence that the higher NLR and monocyte counts, but lower LMR predicted worse PFS; poor RFS was only associated with pretreatment NLR. The subgroup analysis showed that the higher NLR may be a risk factor for prediction of OS only in patients with mCRPC and undergoing chemotherapy, but for PFS in patients with each status and chemotherapy; however, the higher PLR was only significantly associated with OS in localized PCa, but not mCRPC no matter of which therapy strategy.

Compared with the study of Yin et al. [20] (26 vs 14) and Cao et al. (26 vs 21) [21] which investigated the prognostic value of NLR for PCa, our study included more recently published literatures (13, 2016–2018) [12, 14, 18, 29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36, 38]. Also, several articles included in Yin et al. [20] and Cao et al. [21] were excluded because of inconsistent detection method (dNLR, the absolute neutrophil count divided by the difference between white cell and neutrophil counts; not NLR, the absolute neutrophil count divided by the absolute lymphocyte count) [53] or HR (95% CI) crudely extracted from the figures by software which may be inaccurate [54,55,56,57,58]. Thus, our conclusion may be more credible. Although our results seemed not completely similar to other two meta-analysis articles, they all indicated elevated pretreatment NLR was a prognostic predictor of shorter OS in mCRPC, a metastatic PCa. A high NLR indicated the number of neutrophils may increase. There have several studies to demonstrate neutrophilia promoted the metastasis of tumor cells [59, 60]. For example, Donati et al. reported neutrophil counts were elevated in premetastatic lungs in a syngenic mouse model using 4T1 tumor cells. Neutrophils may promote 4T1 cell adhesiveness, invasiveness, and migration by secreting cytokine IL-16, while instillation of an IL-16 neutralizing antibody reversed the effects of neutrophil on tumor cells [59]. Lu et al. proved the decreased release of C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 8, C-C motif chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2), CCL4, and matrix metalloproteinase-9 in neutrophils hampered the migration and invasion of oral squamous cell carcinoma cells [61]. The study of Wculek et al. supported that neutrophil-derived leukotrienes aided the colonization of distant tissue by selectively expanding the sub-pool of cancer cells that retain high tumorigenic potential. Genetic or pharmacologic inhibition of the leukotriene-generating enzyme arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase abrogated the pro-metastatic activity of neutrophils and consequently reduced metastasis [62]. Furthermore, there was also evidence to show neutrophilia facilitates the establishment of metastases by suppressing the anti-tumor activity of IL-17-producing γδ T lymphocytes [63]. Patients with a higher metastatic potential are more prone to die. In line with these studies, we also found pretreatment neutrophilia was an excellent predictor for poor OS.

Compared with the study of Wang et al. [22] on PLR, we included another two recently published literatures [17, 30] to expand the study samples (2994 vs 997). As expected, the results were inconsistent and the positive association between elevated PLR and shorter CSS demonstrated by Wang et al. [22] was not significant in our study. Only the relationship between a high pretreatment PLR and poor OS remained to be significantly demonstrated in both meta-analyses. Furthermore, we, for the first time, performed the subgroup analysis for PLR and the finding implied the higher PLR was only significantly associated with OS in localized PCa regardless of treatment options, but not mCRPC, suggesting PLR may be a prognosis factor for early stage. This conclusion seemed to be in accordance with the tumor proliferation-promoting roles of increased platelets by releasing platelet-derived growth factor and transforming growth factor [64].

Monocytes may reflect the formation of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs). Extensive studies have suggested that monocytes/TAMs exert a pro-tumorigenic effect by the secretion of chitinase-3-like 1 (CHI3L1, YKL-40), interleukin-13 receptorα2 (IL-13Rα2) and then facilitating tumor cell invasion and migration [65, 66]. Thus, monocyte counts have been believed as a clinical prognostic factor for various cancers (including PCa), showing higher infiltration of monocytes predicts poor overall survival [14]. The higher monocytes counts may lead to the lower LMR and thus decreased LMR may be correlated with poor OS (in contrast, high LMR predict more favorable outcomes). This hypothesis was demonstrated in our study and several studies of other cancers [67, 68].

This meta-analysis has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the majority of eligible studies are retrospective which may carry a greater risk of selection bias. Second, the samples size is still not large. Only articles published in English language were included which may miss some studies with negative results published in native language. There were only 6 studies to be included for subgroup analysis of PLR and only two or three datasets enrolled to evaluate the prognostic significance of LMR and monocytes counts, which may result in the overestimation or underestimation of their prognostic values. Third, these inflammatory indicators are easily affected by the patients’ basic state such as age, tumor size, histological type, infection, and other inflammatory diseases. Some eligible studies did not describe these in detail that may cause the presence of heterogeneity. Fourth, inflammatory markers were analyzed in isolation of other prognostic markers. Further studies are needed to see their information value and (possible) influence on therapy in combination with clinical and molecular data. Fifth, all the inflammatory biomarkers were independently studied in the included articles. Thus, which or which combination may be more effective still cannot be confirmed in our study. Sixth, the NLR and PLR cutoff values used in the included studies ranged from 1.73 to 5 for NLR and 117.58 to 190 for PLR. This heterogeneity could hinder the application of these ratios in the clinical setting.

Conclusion

Our meta-analysis preliminarily draw a conclusion that pretreatment elevated blood-based NLR, PLR, neutrophil and monocyte counts, but lower LMR are associated with worse OS in PCa patients. Detection of NLR, monocyte counts, and LMR may represent an inexpensive and easily available method for recurrence and progression prediction and may provide important supporting information to inform treatment decisions and predict potential treatment outcomes. The higher NLR and PLR may be a predominant risk factor for prognosis prediction for patients with mCRPC and localized PCa, respectively.

Abbreviations

- PCa:

-

prostate cancer

- OS:

-

overall survival

- TNM:

-

tumor, node, metastasis

- PSA:

-

prostate-specific antigen

- PLT:

-

platelet

- NLR:

-

neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio

- dNLR:

-

derived NLR

- PLR:

-

platelet–lymphocyte ratio

- LMR:

-

lymphocyte–monocyte ratio

- PFS:

-

progression-free survival

- CSS:

-

cancer-specific survival

- DMFS:

-

distant metastases-free survival

- RFS:

-

recurrence-free survival

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

- HR:

-

hazard ratio

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- NOS:

-

Newcastle–Ottawa Scale

- CCL2:

-

C-C motif chemokine ligand 2

- CHI3L1:

-

chitinase-3-like 1

- IL-13Rα2:

-

interleukin-13 receptorα2

- TAMs:

-

tumor-associated macrophages

References

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(1):7–30.

Xu L, Wang J, Guo B, Zhang H, Wang K, Wang D, Dai C, Zhang L, Zhao X. Comparison of clinical and survival characteristics between prostate cancer patients of PSA-based screening and clinical diagnosis in China. Oncotarget. 2018;9(1):428–41.

Tomioka A, Tanaka N, Yoshikawa M, Miyake M, Anai S, Chihara Y, Okajima E, Hirayama A, Hirao Y, Fujimoto K. Nadir PSA level and time to nadir PSA are prognostic factors in patients with metastatic prostate cancer. BMC Urol. 2014;14(1):3.

Banu A, Oudard S, Banu E, Kamioneur D, Housset M, Thiounn N, Scotte F, Jenabian A, Mejean A, Andrieu JM. Prostate-specific antigen level, stage or Gleason score: which is best for predicting outcomes after radical prostatectomy, and does it vary by the outcome being measured? Results from Shared Equal Access Regional Cancer Hospital database. Int J Urol. 2015;22(4):362–6.

Bakkar R, Gershenson D, Fox P, Vu K, Zenali M, Silva E. Stage IIIC ovarian/peritoneal serous carcinoma: a heterogeneous group of patients with different prognoses. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2014;33(3):302–8.

Falchook AD, Martin NE, Basak R, Smith AB, Milowsky MI, Chen RC. Stage at presentation and survival outcomes of patients with Gleason 8–10 prostate cancer and low prostate-specific antigen. Urol Oncol. 2016;34(3):119.e119–26.

Sfanos KS, De Marzo AM. Prostate cancer and inflammation: the evidence. Histopathology. 2011;60(1):199–215.

Vignozzi L, Maggi M. Prostate cancer: intriguing data on inflammation and prostate cancer. Nat Rev Urol. 2014;11(7):369–70.

Zhu Y, Zhou S, Liu Y, Zhai L, Sun X. Prognostic value of systemic inflammatory markers in ovarian Cancer: a PRISMA-compliant meta-analysis and systematic review. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):443.

Dolan RD, Lim J, Mcsorley ST, Horgan PG, Mcmillan DC. The role of the systemic inflammatory response in predicting outcomes in patients with operable cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):16717.

Sun W, Zhang L, Luo M, Hu G, Mei Q, Liu D, Long G, Hu G. Pretreatment hematologic markers as prognostic factors in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma: neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio and platelet-lymphocyte ratio. Head Neck. 2016;38(S1):E1332–40.

Yasui MHY, Kawahara T, Kumano Y, Miyoshi Y, Matsubara N, Uemura H. Baseline neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio predicts the prognosis of castration-resistant prostate cancer treated with abiraterone acetate. Mol Clin Oncol. 2018;8(4):592–4.

Langsenlehner T, Pichler M, Thurner EM, Krenn-Pilko S, Stojakovic T, Gerger A, Langsenlehner U. Evaluation of the platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic indicator in a European cohort of patients with prostate cancer treated with radiotherapy. Urol Oncol. 2015;33(5):201.e9–16.

Shigeta K, Kosaka T, Kitano S, Yasumizu Y, Miyazaki Y, Mizuno R, Shinojima T, Kikuchi E, Miyajima A, Tanoguchi H. High absolute monocyte count predicts poor clinical outcome in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer treated with docetaxel chemotherapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;195(4):e310.

Linton A, Pond G, Clarke S, Vardy J, Galsky M, Sonpavde G. Glasgow prognostic score as a prognostic factor in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer treated with docetaxel-based chemotherapy. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2013;11(4):423–30.

Zhang GM, Zhu Y, Ma XC, Qin XJ, Wan FN, Dai B, Sun LJ, Ye DW. Pretreatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio: a predictor of advanced prostate cancer and biochemical recurrence in patients receiving radical prostatectomy. Medicine. 2015;94(41):e1473.

Sun Z, Ju Y, Han F, Sun X, Wang F. Clinical implications of pretreatment inflammatory biomarkers as independent prognostic indicators in prostate cancer. J Clin Lab Anal. 2017;32(3):e22277.

Fan LWR, Chi C, Cai W, Zhang Y, Qian H, Shao X, Wang Y, Xu F, Pan J, Zhu Y, Shangguan X, Zhou L, Dong B, Xue W. Systemic immune-inflammation index predicts the combined clinical outcome after sequential therapy with abiraterone and docetaxel for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer patients. Prostate. 2018;78(4):250–6.

Sharma V, Cockerill PA, Viers BR, Rangel LJ, Carlson RE, Karnes RJ, et al. Mp6-05 the association of preoperative neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio with oncologic outcomes following radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer. J Urol. 2015;193:e55–6.

Yin X, Xiao Y, Li F, Qi S, Yin Z, Gao J. Prognostic role of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine. 2016;95(3):e2544.

Cao J, Zhu X, Zhao X, Li XF, Xu R. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio predicts PSA response and prognosis in prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(7):e0158770.

Wang J, Liu Y, Zhang N, Li X, Xin P, Bi J, Kong C. Prognostic role of pretreatment platelet to lymphocyte ratio in urologic cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8(41):70874–82.

Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, Shekelle P, Stewart LA. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ. 2015;349(1):g7647.

Riley RD, Moons KGM, Snell KIE, Ensor J, Hooft L, Altman DG, Hayden J, Collins GS, Debray TPA. A guide to systematic review and meta-analysis of prognostic factor studies. BMJ. 2019;30(364):k4597.

Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle–Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25(9):603–5.

Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–60.

Egger MDSG, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–34.

Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot–based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56(2):455.

Conteduca VCO, Galli L, Maugeri A, Scarpi E, Maines F, Chiuri VE, Lolli C, Kinspergher S, Schepisi G, Santoni M, Santini D, Fratino L, Burgio SL, Salvi S, Menna C, De Giorgi U. Association among metabolic syndrome, inflammation, and survival in prostate cancer. Urol Oncol. 2018;36(5):240.e201–11.

Vidal AC, Howard LE, Hoedt AD, Cooperberg MR, Kane CJ, Aronson WJ, Terris MK, Amling CL, Taioli E, Fowke JH. Neutrophil, lymphocyte and platelet counts, and risk of prostate cancer outcomes in white and black men: results from the SEARCH database. Cancer Causes Control. 2018;29(6):581–8.

Uemura K, Kawahara T, Yamashita D, Jikuya R, Abe K, Tatenuma T, Yokomizo Y, Izumi K, Teranishi JI, Makiyama K. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio predicts prognosis in castration-resistant prostate cancer patients who received cabazitaxel chemotherapy. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:7538647.

Mehra NSA, Lorente D, Dolling D, Sumanasuriya S, Johnson B, Dearnaley D, Parker C, de Bono J. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio in castration-resistant prostate cancer patients treated with daily oral corticosteroids. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2017;15(6):678–84.

Boegemann M, Schlack K, Thomes S, Steinestel J, Rahbar K, Semjonow A, Schrader AJ, Aringer M, Krabbe LM. The role of the neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio for survival outcomes in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer treated with abiraterone. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(2):E380.

Pei XQ, He DL, Tian G, Lv W, Jiang YM, Wu DP, Fan JH, Wu KJ. Prognostic factors of first-line docetaxel treatment in castration-resistant prostate cancer: roles of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in patients from Northwestern China. Int Urol Nephrol. 2017;49(4):629–35.

Buttigliero CPC, Tucci M, Vignani F, Bertaglia V, Iaconis D, Guglielmini P, Numico G, Scagliotti GV, Di Maio M. Prognostic impact of pretreatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in castration-resistant prostate cancer patients treated with first-line docetaxel. Acta Oncol. 2017;56(4):555–62.

Jang WS, Cho KS, Kim KH, Yoon CY, Kang YJ, Lee JY, Ham WS, Rha KH, Hong SJ, Choi YD. Prognostic impact of preoperative neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio after radical prostatectomy in localized prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2016;19(3):298–304.

Lolli CCO, Scarpi E, Aieta M, Conteduca V, Maines F, Bianchi E, Massari F, Veccia A, Chiuri VE, Facchini G, De Giorgi U. Systemic immune-inflammation index predicts the clinical outcome in patients with mCRPC treated with abiraterone. Front Pharmacol. 2015;7:376.

Lee H, Jeong SJ, Hong SK, Byun SS, Lee SE, Oh JJ. High preoperative neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio predicts biochemical recurrence in patients with localized prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy. World J Urol. 2016;34(6):821–7.

Wang Y, Xu F, Pan J, Zhu Y, Shao X, Sha J, Wang Z, Cai Y, Liu Q, Dong B. Platelet to lymphocyte ratio as an independent prognostic indicator for prostate cancer patients receiving androgen deprivation therapy. BMC Cancer. 2016;16(1):329.

Langsenlehner T, Thurner EM, Krenn-Pilko S, Langsenlehner U, Stojakovic T, Gerger A, Pichler M. Validation of the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic factor in a cohort of European prostate cancer patients. World J Urol. 2015;33(11):1661–7.

Bahig H, Taussky D, Delouya G, Nadiri A, Gagnon-Jacques A, Bodson-Clermont P, Soulieres D. Neutrophil count is associated with survival in localized prostate cancer. BMC Cancer. 2015;15(1):594.

Lorente D, Mateo J, Templeton AJ, Zafeiriou Z, Bianchini D, Ferraldeschi R, Bahl A, Shen L, Su Z, Sartor O. Baseline neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) is associated with survival and response to treatment with second-line chemotherapy for advanced prostate cancer independent of baseline steroid use. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(4):750–5.

Yao A, Sejima T, Iwamoto H, Masago T, Morizane S, Honda M, Takenaka A. High neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio predicts poor clinical outcome in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer treated with docetaxel chemotherapy. Int J Urol. 2015;22(9):827–33.

Li F, Hu H, Gu S, Chen X, Sun Q. Platelet to lymphocyte ratio plays an important role in prostate cancer’s diagnosis and prognosis. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8(7):11746–51.

Sonpavde G, Pond GR, Armstrong AJ, Clarke SJ, Vardy JL, Templeton AJ, Wang SL, Paolini J, Chen I, Chow-Maneval E. Prognostic impact of the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2014;12(5):317–24.

Nuhn P, Vaghasia AM, Goyal J, Zhou XC, Carducci MA, Eisenberger MA, Antonarakis ES. Association of pretreatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and overall survival (OS) in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) treated with first-line docetaxel. BJU Int. 2014;114(6b):E11–7.

Shafique K, Proctor MJ, Mcmillan DC, Qureshi K, Leung H, Morrison DS. Systemic inflammation and survival of patients with prostate cancer: evidence from the Glasgow Inflammation Outcome Study. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2012;15(2):195–201.

Yamada Y, Nakamura K, Aoki S, Tobiume M, Zennami K, Kato Y, Nishikawa G, Yoshizawa T, Itoh Y, Nakaoka A. Lactate dehydrogenase, Gleason score and HER-2 overexpression are significant prognostic factors for M1b prostate cancer. Oncol Rep. 2011;25(4):937–44.

Wang YQ, Zhu YJ, Pan JH, Xu F, Shao XG, Sha JJ, Liu Q, Huang YR, Dong BJ, Xue W. Peripheral monocyte count: an independent diagnostic and prognostic biomarker for prostate cancer—a large Chinese cohort study. Asian J Androl. 2017;19(5):579–85.

Templeton AJ, Pezaro C, Omlin A, McNamara MG, Leibowitz-Amit R, Vera-Badillo FE, Attard G, de Bono JS, Tannock IF, Amir E. Simple prognostic score for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer with incorporation of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio. Cancer. 2014;120(21):3346–52.

McDonald AC, Vira MA, Vidal AC, Gan W, Freedland SJ, Taioli E. Association between systemic inflammatory markers and serum prostate-specific antigen in men without prostatic disease—the 2001–2008 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Prostate. 2014;74:561–7.

Poyet C, Adank J-P, Keller E, Mortezavi A, Rabgang T, Pfister B, et al. Mp66-05 pretreatment systemic inflammatory response parameters do not predict the outcome in men with prostate cancer undergoing radical prostatectomy. J Urol. 2015;193:e817.

van Soest RJ, Templeton AJ, Vera-Badillo FE, Mercier F, Sonpavde G, Amir E, Tombal B, Rosenthal M, Eisenberger MA, Tannock IF, de Wit R. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic biomarker for men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer receiving first-line chemotherapy: data from two randomized phase III trials. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(4):743–9.

Minardi D, Scartozzi M, Montesi L, Santoni M, Burattini L, Bianconi M, Lacetera V, Milanese G, Cascinu S, Muzzonigro G. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio may be associated with the outcome in patients with prostate cancer. Springerplus. 2015;4:255.

Kwon YS, Han CS, Yu JW, Kim S, Modi P, Davis R, Park JH, Lee P, Ha YS, Kim WJ, Kim IY. Neutrophil and lymphocyte counts as clinical markers for stratifying low-risk prostate cancer. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2016;14(1):e1–8.

Sümbül AT, Sezer A, Abalı H, Köse F, Gültepe I, Mertsoylu H, Muallaoğlu S, Özyılkan Ö. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio predicts PSA response, but not outcomes in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer treated with docetaxel. Int Urol Nephrol. 2014;46(8):1531–5.

Nakagami Y, Nakashima J, Ohno Y, Makoto O, Tachibana M. Prognostic value of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and establishment of novel risk stratification model in castration-resistant prostate cancer patients treated with docetaxel chemotherapy. J Urol. 2015;193(4):e1084.

Keizman D, Gottfried M, Ish-Shalom M, Maimon N, Peer A, Neumann A, Rosenbaum E, Kovel S, Pili R, Sinibaldi V, Carducci MA, Hammers H, Eisenberger MA, Sella A. Pretreatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer patients treated with ketoconazole: association with outcome and predictive nomogram. Oncologist. 2012;17(12):1508–14.

Donati K, Sépult C, Rocks N, Blacher S, Gérard C, Noel A, Cataldo D. Neutrophil-derived interleukin 16 in premetastatic lungs promotes breast tumor cell seeding. Cancer Growth Metastasis. 2017;10:1179064417738513.

Spicer JD, Mcdonald B, Coolslartigue JJ, Chow SC, Giannias B, Kubes P, Ferri LE. Neutrophils promote liver metastasis via Mac-1-mediated interactions with circulating tumor cells. Cancer Res. 2012;72(16):3919–27.

Lu H, Wu B, Ma G, Zheng D, Song R, Huang E, Mao M, Lu B. Melatonin represses oral squamous cell carcinoma metastasis by inhibiting tumor-associated neutrophils. Am J Transl Res. 2017;9(12):5361–74.

Wculek SK, Malanchi I. Neutrophils support lung colonization of metastasis-initiating breast cancer cells. Nature. 2015;528(7582):413–7.

Coffelt SB, Kersten K, Doornebal CW, Weiden J, Vrijland K, Hau CS, Njm V, Ciampricotti M, Ljac H, Jonkers J. IL-17-producing γδ T cells and neutrophils conspire to promote breast cancer metastasis. Nature. 2015;522(7556):345–8.

Cheng J, Ye H, Liu Z, Xu C, Zhang Z, Liu Y, Sun Y. Platelet-derived growth factor-BB accelerates prostate cancer growth by promoting the proliferation of mesenchymal stem cells. J Cell Biochem. 2013;114(7):1510–8.

Cavassani KAMR, Habiel DM, Chen JF, Montes A, Tripathi M, Martins GA, Crother TR, You S, Hogaboam CM, Bhowmick N, Posadas EM. Circulating monocytes from prostate cancer patients promote invasion and motility of epithelial cells. Cancer Med. 2018;7(9):4639–49.

Tsagozis P, Augsten M, Pisa P. All trans-retinoic acid abrogates the pro-tumorigenic phenotype of prostate cancer tumor-associated macrophages. Int Immunopharmacol. 2014;23(1):8–13.

Guo YH, Sun HF, Zhang YB, Liao ZJ, Zhao L, Cui J, Wu T, Lu JR, Nan KJ, Wang SH. The clinical use of the platelet/lymphocyte ratio and lymphocyte/monocyte ratio as prognostic predictors in colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2017;8(12):20011–24.

Lin B, Chen C, Qian Y, Feng J. Prognostic role of peripheral blood lymphocyte/monocyte ratio at diagnosis in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a meta-analysis. Leuk Lymphoma. 2015;56(9):2563–8.

Authors’ contributions

HP and XGL collected, extracted performed quality assessment and analyzed the data; HP conceived, designed this study and wrote the paper. All authors reviewed the final manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

None.

Competing interests

The authors declared no potential competing interests with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Peng, H., Luo, X. Prognostic significance of elevated pretreatment systemic inflammatory markers for patients with prostate cancer: a meta-analysis. Cancer Cell Int 19, 70 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12935-019-0785-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12935-019-0785-2