Abstract

Background

Childhood trauma increases the risk for adult obesity through multiple complex pathways, and the neural substrates are yet to be determined.

Methods

Participants from three population-based neuroimaging cohorts, including the IMAGEN cohort, the UK Biobank (UKB), and the Human Connectome Project (HCP), were recruited. Voxel-based morphometry analysis of both childhood trauma and body mass index (BMI) was performed in the longitudinal IMAGEN cohort; validation of the findings was performed in the UKB. White-matter connectivity analysis was conducted to study the structural connectivity between the identified brain region and subdivisions of the hypothalamus in the HCP.

Results

In IMAGEN, a smaller frontopolar cortex (FPC) was associated with both childhood abuse (CA) (β = − .568, 95%CI − .942 to − .194; p = .003) and higher BMI (β = − .086, 95%CI − .128 to − .043; p < .001) in male participants, and these findings were validated in UKB. Across seven data collection sites, a stronger negative CA-FPC association was correlated with a higher positive CA-BMI association (β = − 1.033, 95%CI − 1.762 to − .305; p = .015). Using 7-T diffusion tensor imaging data (n = 156), we found that FPC was the third most connected cortical area with the hypothalamus, especially the lateral hypothalamus. A smaller FPC at age 14 contributed to higher BMI at age 19 in those male participants with a history of CA, and the CA-FPC interaction enabled a model at age 14 to account for some future weight gain during a 5-year follow-up (variance explained 5.8%).

Conclusions

The findings highlight that a malfunctioning, top-down cognitive or behavioral control system, independent of genetic predisposition, putatively contributes to excessive weight gain in a particularly vulnerable population, and may inform treatment approaches.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Overweight and obesity affect one third of adults in developed countries [1], and life expectancy could be shortened by 2–4 years for those who became obese [2]. Obesity interventions are effective in the short term, but subsequent weight regain often occurs: long-term weight management is a primary treatment challenge [3]. Identifying the contributors to long-term weight gain will be essential for combating the obesity epidemic [4, 5].

Long-term weight management involves more than detecting physiological signals about hunger or satiety: cognitive control is required to resist urges to eat and helps avoid or shift attention away from food cues in the environment or retrieved from memory [6]. The hypothalamus is a center for eating behavior, while the prefrontal cortex is critical for cognitive control: Given their reciprocal connections, observed in animal models [7,8,9], early-life damage to this neurocognitive system may impair both motivation and capability for long-term weight management [10]. For example, a 2017 study has demonstrated that compared with the controls, a chronic early-life stress (ES; between P2 and P9) mouse model actually had reduced mRNA expression of leptin lasting to adulthood and both reduced total body fat mass and impaired learning and memory in adulthood; however, compared with the control mice, the mice exposed to a moderate western-style diet showed higher body fat accumulation at P98 as compared to P42 [11]. However, this has been difficult to test in humans using randomized clinical trials. In observational studies, childhood trauma has been identified as a key environmental risk factor that can disrupt brain development [12, 13] and increase risk for obesity [14, 15]. We therefore harnessed a population-based longitudinal neuroimaging cohort in an effort to identify a neurocognitive control (NcC) pathway relating to childhood trauma and the risk for obesity.

Human studies have begun to reveal enduring effects of childhood trauma on neural systems [12], including reduced gray matter volume (GMV) in the prefrontal cortex [16] and ventral striatum [17]; however, neural contributions to an NcC pathway remain to be determined. Neural changes after childhood trauma are additionally modulated by sex [18]: brain development is sex-dimorphic [19] and an NcC pathway may be sex-dimorphic as well. Obesity itself can affect the brain [20, 21]: evidence of neural changes temporarily preceding excessive weight gain would further strengthen the case for an NcC pathway. To address these questions, we analyzed data from the IMAGEN longitudinal neuroimaging study of adolescents [22].

We hypothesized that some structural changes in the brain might link the childhood trauma to higher body mass index (BMI). To identify the candidate brain structures to serve as this link, we first conducted a whole-brain voxel-wise association study (BWAS) of GMV to identify overlapping neuroanatomical correlates between childhood trauma and higher body mass index (BMI) using the IMAGEN sample. To account for the sex-dimorphic in brain development, we conducted this BWAS for females and males separately. To ensure specificity of our finding, we accounted for potential confounding factors: polygenetic risk for obesity [23], family socioeconomical status [24], changes due to illegal drug use [25], and elevated depressive symptoms [26]. To validate and extend our results to a wider age range, we sought to replicate our findings using an independent sample with a mean age of 56.89 years (UK Biobank [27]). Next, we mapped white-matter connectivity between the hypothalamus and the cortical areas, to explore the potential structural basis for supporting cognitive control over eating behavior mediated by the hypothalamus. Given that the hypothalamus is a small structure (~ 1 cm3), we analyzed the 7-Tesla (7-T) diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) data from the Human Connectome Project [28] with a high spatial resolution (1.5 × 1.5 × 1.5 mm3). Finally, to understand the directionality of the identified associations, we conducted a longitudinal analysis in the IMAGEN cohort to test whether neural correlates of childhood trauma at age 14 preceded excessive weight gain during a 5-year follow-up period.

Methods

Participants

Discovery sample

IMAGEN is a multicenter longitudinal study of healthy youths in Europe [22]. The database we used was released in June 2016. Briefly, 2087 participants were recruited at age 14, and among them, 1650 returned for follow-up at age 19. The inclusion criteria included (1) participants with childhood maltreatment assessment, (2) with BMI information at both time points, and (3) structural images at both time points. The exclusion criterion was participants who were underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2) at follow-up. After data quality controls in all these domains—neuroimaging (n = 949) and behavioral assessments (trauma: n = 1159, and BMI: n = 1042) at both baseline and follow-up, 639 young adults (325 females) with a mean (SD) age of 19.06 (.70) were included in the current study. Of these, 557 adolescents (278 females) had genetic information (Table 1, Additional file 1: Method S1 [22, 29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45]).

Validation sample

UK Biobank (UKB) is a large population-based cohort study of adults in the UK. After quality controls for neuroimaging data and behavioral assessments, 4121 participants (2396 females) with a mean (SD) age of 56.89 (5.02) years were included (Additional file 1: Method S2 and Table S1).

White-matter connectivity sample

Human Connectivity Project (HCP 1200 Subject Release; Last Updated: April 2018) from the Washington University in St. Louis–University of Minnesota (WU-Minn HCP) Consortium provided 178 participants (109 females; mean [SD] age of 29.5 [3.33] years) with 7-T diffusion magnetic resonance imaging (dMRI) after preprocessing [39,40,41].

Measurements

Anthropometric indices

Weight and height were measured to calculate BMI [weight(kg)/height(m)2]. Overweight was defined as 30 kg/m2 > BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2, obesity as BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2.

Childhood trauma

The well-established Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ [29, 46,47,48]) was used to assess the history of childhood trauma before the age of 19 in IMAGEN, including abuse (emotional, physical, and sexual) and neglect (emotional and physical). Since the participants in the IMAGEN study were healthy subjects, we used the lowest cut-off as 8 for EA, 7 for PA, 5 for SA, 9 for EN, and 7 for PN [29]. If any type of abuse/neglect occurred, abuse/neglect was scored as “1”; if not, a score of “0” was recorded (Additional file 1: Method S1). In UKB, the following questions were asked: physically abused by family member as a child (Field ID: 20488), felt hated by family members as a child (Field ID: 20487), and sexually molested as a child (Field ID: 20490) (Additional file 1: Method S2).

Neuroimaging data

In IMAGEN, T1-weighted images were collected using 3-T scanners and the ADNI protocols [33]. UKB used a Siemens Skyra 3-T scanner with a 3D MPRAGE protocol (Additional file 1: Method S2). All data were preprocessed in SPM8 using the VBM8 toolbox, including the segmentation, normalization, modulation, and smoothing. The resulting voxel size was 1.5 × 1.5 × 1.5 mm3 (Additional file 1: Method S1). HCP used a Siemens 7-T MAGNETOM scanner with a high spatial resolution of 1.05 mm isotropic (Additional file 1: Method S3) [49].

Polygenic risk score

Polygenic risk scores (PRSs) for higher BMI (PRSBMI) were calculated using the PRSice software (http://prsice.info/) [35]. To generate PRSBMI in IMAGEN, we used GWAS summary data from GIANT, which included 2,554,637 SNPs and up to 339,224 individuals of European ancestry [36] (Additional file 1: Method S1).

Statistical analysis

Behavioral association analysis

We applied linear regression models to evaluate the relationships between childhood trauma and BMI measured at age 19 in male and female separately, controlling for data collecting site. The false discovery rate (FDR) correction was employed to control for multiple comparisons. Then in the sensitivity analysis, we tested the confounding effects of PRSBMI, family socioeconomic status, stressful life events in the past year, birth weight, depressive symptoms, and illegal drug use (Additional file 1: Method S1). Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics, Version 22. The coefficient (unstandardized, β) of the linear regression models and its 95% confidence interval (CI) were reported.

Structural association analysis

We conducted a voxel-wise association study of GMV with either childhood abuse, PRSBMI, or BMI at age 19 years, in the female and male participants, separately. We focused our analysis on gray matter (i.e., 380,537 voxels defined by the automatic anatomic labeling atlas [50]) and considered the following covariates: data collecting site, handedness, and total intracranial volume (TIV). We identified significant clusters by permutation-based TFCE (Threshold-Free Cluster Enhancement, 5000 permutations, no acceleration method, p < .05, 2-tailed) [51] with cluster size greater than 217 voxels (approximately 4/3 × π × [3.3970 × 1.645]3/1.53 voxels falling into the 90% confidence interval of the smoothing kernel [33]). We defined the overlapping clusters that were associated with both CA and BMI as the abuse ROIs. In the following analyses, we focused on the gray matter volumes of the abuse ROIs. To test whether stronger abuse-brain association was correlated with stronger abuse-BMI association, we calculated the correlation between these two associations across multiple sites of data collection.

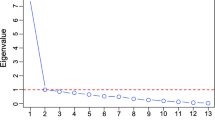

White-matter connectivity analysis

The pre-processed 7-T dMRI data were downloaded from the ConnectomeDB, which is a data sharing platform provided by HCP (http://db.humanconnectome.org) [52]. We used state-of-the-art brain atlases, including HCP-MMP (multi-modal parcellation) for cortical areas [44] and CIT168 (California Institute of Technology) for the hypothalamus [45]. The cortical connectivity of the hypothalamus (HTH; 8 subdivisions defined by lateral-medial and anterior-posterior; Additional file 1: Figure S1) was counted as the number of reconstructed tracks ending in each cortical area using DSI Studio (http://dsi-studio.labsolver.org). Combining one-sample sign test with false discovery rate, we assessed whether the median of the fiber number (FN) estimated for one brain area was greater than the randomly assigned FN according to the size of this area (Additional file 1: Method S3).

Mediation analysis

We tested the mediation effect of the FPC volume at age 19 on the association between childhood abuse and BMI at age 19, while controlling for data collecting site, handedness, TIV, and PRSBMI. We applied a bootstrap procedure provided by PROCESS in SPSS (http://www.processmacro.org/) to test the mediation (indirect) effect. A significant indirect effect was identified when the bootstrap confidence interval did not include zero.

Cross-lagged panel analysis

To determine the directionality of the relationship between the GMV of the abuse ROI identified above and the BMI in the group with childhood abuse, we employed a two-wave cross-lagged panel model (CLPM) [53] using the data collected at ages 14 and 19 with the Mplus Version 7. The FDR was applied to correct for multiple comparisons between the cross-lagged coefficients of the BMI➔GMV and the GMV➔BMI directions. Furthermore, we compared this longitudinal association between the groups with and without childhood abuse by the multi-group analysis of CLPM. We considered the following covariates: data collecting site, handedness, baseline TIV, PRSBMI, and family socioeconomic status. Significance levels were given by 5000 bootstraps.

Results

Childhood abuse associated with higher BMI independent of genetic risk

For IMAGEN, we found that young adults with a history of childhood abuse (CA) had higher BMI compared with those without (β = 1.018, 95%CI .292 to 1.745; p = .006). This effect was significant in male participants (β = 1.445, 95%CI .418 to 2.471; p = .006, FDR-p = .012; Fig. 1a), but not in female participants (β = .543, 95%CI − .491 to 1.577, p = .30). The PRSBMI was correlated with BMI in both sexes (male: β = 1.237, 95%CI .783 to 1.690; p < .001; female: β = .785, 95%CI .303 to 1.268; p = .001; Fig. 1b). Moreover, this association in male participants remained significant after controlling for both PRSBMI (β = 1.119, 95%CI .068 to 2.170; p = .037) and other possible confounders, such as family socioeconomic status, stressful life events in the past year, birth weight, depressive symptoms, and illegal drug use (Additional file 1: Table S2). The PRSBMI-by-CA interaction effect on BMI in the male participants did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.321).

Association between childhood abuse, PRSBMI, and BMI. a Childhood abuse associated with higher rate of overweight and obesity in male participants, but not in female participants in the IMAGEN study. b Polygenic risk for obesity associated with BMI’s in both male and female participants in the IMAGEN study. c Childhood abuse associated with higher BMI in both male and female participants in the UK Biobank. d Polygenic risk for obesity associated with BMI in both male and female participants in the UK Biobank. NoCA, no childhood abuse; CA, childhood abuse; OB, obesity; OW, overweight; NW, normal weight

Smaller frontopolar cortex associated with both childhood abuse and higher BMI

We first confirmed a previous finding [54] that lower GMV of a frontopolar cluster was associated with both greater PRSBMI and higher BMI in male participants from IMAGEN (Additional file 1: Table S3). This demonstrated that the brain volume associations identified in this manner are replicable. Using the same approach, we then identified that lower GMV of a frontal cluster was associated with CA (Additional file 1: Table S3). The abuse-cluster overlapped with the BMI-cluster in the FPC (Fig. 2a). No significant neuroanatomical association was identified for CA in the female brains in IMAGEN. The association between childhood abuse and smaller FPC volume in male participants remained significant after controlling for both PRSBMI and other possible confounders (Additional file 1: Table S4). The FPC volume was smaller in male than in female participants at ages 19 (β = − .431, 95%CI − .660 to − .203, p < .001), and a significant interaction effect was observed between CA and sex on the volume of the FPC (β = − .824, 95%CI − 1.351 to − .296, p = .002). We found that smaller FPC was correlated with greater negative abuse-FPC association across the 6 data collection sites of IMAGEN (β = .002, 95%CI .001 to .002; p = .002; Fig. 3a). FPC volume was not associated with depressive symptoms (n = 285; r = .05; p = .4) or lifetime illegal drug use (n = 264; r = − .11; p = .1 after controlling for BMI).

Brain regions associated with childhood trauma, genetic risk for higher BMI, and BMI. a The significant brain regions with GMV associated with both childhood abuse and BMI (marked by blue and pink), associated with both genetic risk and BMI (marked by green and pink), and the overlapped brain regions (i.e., brain regions associated with childhood abuse, genetic risk, and BMI, marked by pink) in male participants from the IMAGEN study. b, c The significant brain regions with GMV associated with variables mentioned above in male or female participants from the UK Biobank. Gray dotted line roughly marked the inner contour of the frontopolar cortex. GMV, gray matter volume; CA, childhood abuse; BMI, body mass index; PRSBMI, polygenic risk score for obesity

Associations were coupled between abuse-BMI and abuse-brain. a Smaller volume of the FPC was associated with deeper negative association between CA and the FPC volume (CA-FPC assoc) across both male (gray dots) and female (blue dots) subjects at the 6 data collection sites in the IMAGEN cohort. The FPC volume shown here was the ratio between the raw FPC volume and the TIV. b The partial correlation coefficient between CA and BMI was associated with the partial correlation coefficient between CA and the FPC volume in male subjects across the 6 data collection sites in the IMAGEN study and the UK Biobank sample. c Significant cortical connectivity of the hypothalamus using 7-T dMRI data from HCP. The fiber number was normalized as a percentage of the connections tracked between one brain region and one subdivision of the hypothalamus among all its tracked connections. The connections survived the FDR correction were reported. The upper plot shows the median of the fiber number, the middle plot marks the significant connectivity in black, and the lower plot shows the significant differences in connectivity between lateral and medial hypothalamus. The abbreviations of the cortical parcels are defined by the HCP-MMP atlas. The hypothalamus was divided into 8 subdivisions along the anterior-posterior and the medial-lateral lines. L, left; R, right; AL, anterior lateral; AM, anterior medial; PL, posterior lateral; PM, posterior medial. d One exemplar of the fiber tracking results. Only the fibers ending in the hypothalamus (marked in red, defined by the CIT168 atlas) were shown. The surface views of the white matter connectivity of the lateral (e) and the medial (f) hypothalamus. The maximum of the connectivity (normalized fiber number, %) between the anterior and posterior parts of either the lateral or the medial hypothalamus. FPC, frontopolar cortex; CA, childhood abuse; TIV, total intracranial volume; BMI, body mass index; HTH, hypothalamus

Replication using a larger cohort

In UKB, we found that CA was associated with higher BMI in both sexes after controlling for PRSBMI (male: β = .790, 95%CI .317 to 1.263; p = .001; female: β = 1.039, 95%CI .564 to 1.514; p < .001; Fig. 1c, d), and the effect size of the trauma-BMI association remained at a comparable level between the IMAGEN and UKB cohorts (.32 kg/m2 in males from IMAGEN and .17 kg/m2 in males from UKB; Additional file 1: Table S5). Regardless of age-related effects on the brain [55], we were able to confirm that smaller FPC was associated with both CA and higher BMI in male participants (n = 1725) from UKB (Fig. 2b; Additional file 1: Table S6). Consistent with the behavioral association, we identified that an FPC cluster with lower GMV was associated with both CA and higher BMI in female participants (n = 2396) from UKB (Fig. 2c; Additional file 1: Table S7). Considering PRSBMI as an additional covariate, these volumes were still associated with CA (male: β = − .194, 95%CI − .308 to − .081; p = .001; female: β = − .164, 95%CI − .255 to − .073; p < .001; controlling for BMI) and BMI (male: β = − .044, 95%CI − .057 to − .031; p < .001; female: β = − .064, 95%CI − .073 to − .055; p < .001; controlling for CA).

Stronger abuse-BMI association coupled with stronger abuse-brain association

Across the 6 data collection sites in IMAGEN and the UKB cohort, we found that greater negative abuse-brain association was correlated with a stronger positive abuse-BMI association in male participants (β = − 1.033, 95%CI − 1.762 to − .305; p = .015; Fig. 3b), but such coupling weakened in female participants (z = − 1.94, p1-tailed = .03; Additional file 1: Figure S2).

Frontopolar cortex is structurally connected with a hypothalamic center of eating behavior

Using dMRI data from HCP (n = 156), we examined the structural connectivity between each of the 8 subdivisions of the hypothalamus (i.e., divided using the anterior-posterior parts by the lateral-medial parts in both hemispheres; Additional file 1: Figure S1) and 374 brain regions (i.e., 360 cortical regions and 14 subcortical regions). We found 28 cortical areas and 7 subcortical areas had significant white matter connections with the hypothalamus after FDR correction (Fig. 3c, d; Additional file 2). The strongest connectivity was between the left dorsal temporal gyrus (L_TGd) and the left anterior lateral hypothalamus (L_AL; median of the normalized fiber number: 10%; FDR-p < .001; Fig. 3e). The most polar subdivision of Brodmann area (BA) 10 in the right hemisphere (R_10pp), ranked as the third most connected cortical areas, had significant connections with both the posterior (2.2%; FDR-p < .001) and anterior (1.0%; FDR-p < .001) lateral hypothalamus (Fig. 3e). At the right anterior hypothalamus, R_10pp was connected much stronger to the lateral hypothalamus compared with the medial hypothalamus (FDR-p = .009; Fig. 3f; Additional file 1: Figure S3).

From cross-sectional association to longitudinal prediction

In male participants at age 19 from IMAGEN, we found the smaller FPC cluster was associated with both higher BMI (β = − .086, 95%CI − .128 to − .043; p < .001; Fig. 4a) and CA (β = − .568, 95%CI − .942 to − .194; p = .003; Fig. 4b), in a linear regression model including BMI, CA, and PRS as predictors for FPC volume (n = 279). We identified a significant mediation effect of the volume of FPC on the association between childhood abuse and higher BMI (indirect effect = .542, standard error [SE] = .229, 95%CI = .164–1.064), explaining 46.4% of the total effect. Longitudinally, we found a cross-lagged correlation from baseline FPC to follow-up BMI in males with a history of CA (Volume14 to BMI19: β = − .299, 95%CI − .599 to − .020; p = .042, FDR-p = .042; n = 62; Fig. 4c and Additional file 1: Figure S4), and this correlation was weakened in males without such a history (βca–βno-ca = .324, 95%CI .045 to .640; p = .03). Across both groups, the CA-FPC interaction at baseline was associated with weight gain (∆BMI) during the 5-year follow-up (interaction term: β = − .343, 95%CI − .635 to − .051; p = .02; Fig. 4d; polygenetic risk: β = .367, 95%CI .040 to .694; p = .03; the whole model: adjusted-R2 = 5.8%; p = .005; n = 278; Additional file 1: Table S9).

Associations among frontopolar volumes, childhood trauma, and BMI in the IMAGEN study. a-b The associations of the frontopolar volume with both childhood abuse and BMI in male participants at age 19 years. The frontopolar volumes were identified as the GMVs of brain region associated with both childhood abuse and BMI (marked by blue and red in Fig. 2a). These cross-sectional analyses indicated two potential paths among childhood abuse, frontopolar volume, and BMI. c Cross-lagged panel analysis between frontopolar volume and BMI. In males who did not experience childhood abuse, baseline BMI was significantly associated with frontopolar volume at follow-up (up); while in males who did experience childhood abuse, paths existed at both directions (down). d Association between BMI at age 14 years and frontopolar volumetric change between age 14 and 19; these analyses based on longitudinal designs indicated the interaction between the frontopolar volume at age 14 years and childhood abuse contributed to explaining weight gain. NoCA, no childhood abuse; CA, childhood abuse; BMI, body mass index

Discussion

We found that volumetric shrinkage of the FPC (BA10 and BA32) quantitatively linked CA to adult overweight or obesity. As the FPC is at the apex of a cognitive and motivational control hierarchy [56], the current findings provide a neuroanatomical basis for the hypothesis that cognitive deficits after CA contribute significantly to adult obesity (i.e., the “NcC pathway”). Our observation that brain changes precede excessive weight gain may indicate that strengthening higher order cognitive control systems could decrease the risk for developing obesity in this population.

Remarkably, our findings suggest a novel top-down control pathway underlying CA-induced excessive weight gain. This fronto-polar region of the prefrontal cortex has been placed at the apex of the cognitive control hierarchy [57,58,59]. The lateral FPC has been related to inhibitory control, while the medial FPC has been associated with both emotion and reward processing [59]. Notably, the region we identified was located in the transition zone between the lateral FPC and medial FPC and so may participate in both processes. Thus, some studies have found, associated with excessive future weight gain a few years later, increased activation of reward regions occurring in response to palatable food [60, 61] or food cues [62, 63], while others have found that reduced volumes [64] or abnormal activity [65] in the prefrontal inhibitory control regions could predict future increases in BMI. In this study, we did not employ any cognitive or behavioral tests to enable us to determine which were the most important of these behavioral factors.

The findings on FPC provide new evidence on how higher-order cognitive and motivational control may be essential for success in weight management [10]. This may be relevant for “resisting temptation”: the frontal pole has been implicated in deciding to avoid situations requiring difficult motivational choices—the temporal discounting of reward [66]—consistent with hierarchical models of cognitive control [56]. This could correspond, for example, to better adherence to dietary strategies of avoiding exposure to appealing yet high calorie food [57]. Control of food intake could have unique features compared with controlling other behavior, as human choice strategies may have been shaped by evolution to take as much food as is encountered. This may be particularly true when dieting begins to produce weight loss, which has been associated with decreased leptin and increased ghrelin levels in blood, changes that have been associated with increased PFC activity in response to food cues [67]. Our results may partly explain why dieting for long-term weight management is so difficult [68]. Instead of repeatedly resisting opportunities to eat food encountered in the environment, higher-order cognitive control via FPC could enable the strategic avoidance of fast-food outlets and even the kitchen (and opening the refrigerator) when trying to lose weight [66]. Cognitive control in 3-year-olds predicts their weight status [69] 30 years [70] later, and our finding of reduced FPC volume associated with higher BMI may provide a neuroanatomical basis for this observation. In the extreme case of anorexia nervosa, the frontal pole is over-activated upon presentation of high-calorie stimuli compared to healthy controls [71].

Notably, the finding of a strong white-matter connection between the FPC and the eating behavior center (i.e., the hypothalamus) [72] provides a structural basis for the neurocognitive control of eating behavior. The FPC cluster we identified is located in the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC; mainly BA24, BA25, BA32, and BA10) [8], and this network provides the origin of most of frontal projections to the hypothalamus in both rats [73] and monkeys [9]. It has long been hypothesized that the communication between the hypothalamus and the cortical regions may influence food choices, based on the observations that the reward value of food can be influenced by metabolic state [74]. Human resting-state functional connectivity has been reported between the PFC and the hypothalamus [75], and there is evidence for structural connectivity between these regions in the primate brain [9], but this has not yet been confirmed for the human brain due to the small volume of the hypothalamus and the complexity of its connectivity [76, 77]. Using 7-T dMRI data from a large sample (n = 156), with high spatial resolution (voxel size = 1.05 × 1.05 × 1.05 mm3), we found that the most polar subdivision of BA10 (i.e., R_10pp) ranked as the third most connected cortical area to the hypothalamus, especially the lateral hypothalamus among 360 cortical regions defined by the latest HCP-MMP (multi-modal parcellation) atlas. This finding may generate a testable hypothesis that the strength of this connection may be associated with the excessive weight gain, especially after the exposure to childhood abuse. We could not test this association using the HCP sample, since the childhood trauma was not assessed in this cohort.

Our findings suggest that larger FPC volume may be protective against higher BMI associated with CA. The smaller the FPC volume, the stronger was the abuse-brain association across different data collection sites, and the increased abuse-brain association was in turn correlated with the stronger abuse-BMI association. We also demonstrated that a smaller FPC volume at baseline significantly contributed to the prediction of weight gain at follow-up. Our sexually dimorphic results provide further support that the smaller the FPC volume, the greater were the effect sizes of these associations. The FPC volume was smaller in male than in female participants, which is consistent with a 2014 meta-analysis of sex difference at a regional level [19]. We had similar statistical power for both female (n = 325) and male (n = 314) participants in IMAGEN, but we could identify a significant FPC cluster associated with CA in males only, indicating the effect size of the abuse-brain association was smaller in the females from the IMAGEN sample. The effect size of the abuse-BMI association was also smaller in female than in male participants at a trend level (p = .08) in this sample. Both the abuse-FPC and abuse-BMI associations became significant in the much larger and also older UKB sample of female participants (n = 2396). The identified sex differences are also supported by both animal models for childhood trauma [78] and human epidemiological studies on the trauma-obesity association [79].

These findings of sex difference may suggest that sex hormones such as testosterone might be involved in the excessive weight gain in adolescent males after the exposure childhood trauma. Low testosterone levels have been implicated in metabolic dysfunction, especially associated with increased central adiposity and reduced lean mass in males, while weight loss has also been linked to increased testosterone levels [80]. Childhood trauma has been associated with negative testosterone-cortisol coupling in adolescent females, but positive testosterone-cortisol coupling in adolescent males [81], since childhood trauma can alter the coupling between hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis and hypothalamus-pituitary-gonadal [82].

The present findings may be important clinically. Consistent with previous reports [14, 83], the CA prevalence was as high as 1 in 4 young male participants in our sample, and the risk of being overweight or obese at age 19 was 2.17-fold higher than those without exposure to CA (n = 314, OR = 2.168, 95%CI 1.244 to 3.777; p = .006). Non-invasive brain stimulation therapies [84], such as transcranial magnetic stimulation and transcranial direct current stimulation, are already applied for the treatment of obesity and eating disorders. To date, most studies have targeted the dorsolateral PFC, but therapeutic effects have been inconclusive [84]. Our findings therefore identify the FPC as a novel brain target for the treatment of obesity.

Limitations

The present study had several limitations. First, because this is an observational study, any suggestion of causal associations must be considered with caution. Second, given the complex role of the frontopolar cortex, future neuroimaging experiments are required to examine effects on down-stream networks. Third, detailed cognitive or behavioral assessments will be useful in future studies to elucidate the contributions of different control functions to excessive weight gain after childhood abuse.

Conclusions

We have identified volumetric reduction in FPC as a key neuroanatomical link between childhood abuse and adult obesity. This finding highlights the importance of higher-order cognitive control in weight management. Development of cognitive intervention strategies to compensate for the possible resultant functional deficiencies is warranted.

Availability of data and materials

The IMAGEN data are available by application to the consortium coordinator Dr. Schumann (http://imagen-europe.com) after evaluation according to an established procedure. UK Biobank is an open Resource and is available to researchers by registering and applying to access the Resource via the Resource Access Management System (http://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/). This research has been conducted using the UK Biobank Resource under application 19542. The 7-T DTI data were provided by the Human Connectome Project, WU-Minn Consortium (Principal Investigators: David Van Essen and Kamil Ugurbil; https://www.humanconnectome.org/).

References

Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Lawman HG, Fryar CD, Kruszon-Moran D, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Trends in obesity prevalence among children and adolescents in the United States, 1988-1994 through 2013-2014. JAMA. 2016;315(21):2292–9.

Prospective Studies C, Whitlock G, Lewington S, Sherliker P, Clarke R, Emberson J, Halsey J, Qizilbash N, Collins R, Peto R. Body-mass index and cause-specific mortality in 900 000 adults: collaborative analyses of 57 prospective studies. Lancet. 2009;373(9669):1083–96.

Hall KD, Kahan S. Maintenance of lost weight and long-term management of obesity. Med Clin North Am. 2018;102(1):183–97.

Heymsfield SB, Wadden TA. Mechanisms, pathophysiology, and management of obesity. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(3):254–66.

MacLean PS, Wing RR, Davidson T, Epstein L, Goodpaster B, Hall KD, Levin BE, Perri MG, Rolls BJ, Rosenbaum M, et al. NIH working group report: Innovative research to improve maintenance of weight loss. Obesity. 2015;23(1):7–15.

Davidson TL, Jones S, Roy M, Stevenson RJ. The cognitive control of eating and body weight: it’s more than what you “think”. Front Psychol. 2019;10:62.

Kita H, Oomura Y. Reciprocal connections between the lateral hypothalamus and the frontal complex in the rat: electrophysiological and anatomical observations. Brain Res. 1981;213(1):1–16.

Öngür D, Price JL. The organization of networks within the orbital and medial prefrontal cortex of rats, Monkeys and Humans. Cereb Cortex. 2000;10(3):206–19.

Öngür D, An X, Price JL. Prefrontal cortical projections to the hypothalamus in macaque monkeys. J Comp Neurol. 1998;401(4):480–505.

Lowe CJ, Reichelt AC, Hall PA. The prefrontal cortex and obesity: a health neuroscience perspective. Trends Cogn Sci. 2019;23(4):349–61.

Yam KY, Naninck EFG, Abbink MR, la Fleur SE, Schipper L, van den Beukel JC, Grefhorst A, Oosting A, van der Beek EM, Lucassen PJ, et al. Exposure to chronic early-life stress lastingly alters the adipose tissue, the leptin system and changes the vulnerability to western-style diet later in life in mice. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2017;77:186–95.

Teicher MH, Samson JA, Anderson CM, Ohashi K. The effects of childhood maltreatment on brain structure, function and connectivity. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2016;17(10):652–66.

Birn RM, Roeber BJ, Pollak SD. Early childhood stress exposure, reward pathways, and adult decision making. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2017;114(51):13549.

Danese A, Tan M. Childhood maltreatment and obesity: systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2014;19(5):544–54.

Gardner R, Feely A, Layte R, Williams J, McGavock J. Adverse childhood experiences are associated with an increased risk of obesity in early adolescence: a population-based prospective cohort study. Pediatr Res. 2019;86(4):522–8.

Gorka AX, Hanson JL, Radtke SR, Hariri AR. Reduced hippocampal and medial prefrontal gray matter mediate the association between reported childhood maltreatment and trait anxiety in adulthood and predict sensitivity to future life stress. Biol Mood Anxiety Disord. 2014;4:12.

Edmiston EE, Wang F, Mazure CM, Guiney J, Sinha R, Mayes LC, Blumberg HP. Corticostriatal-limbic gray matter morphology in adolescents with self-reported exposure to childhood maltreatment. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165(12):1069–77.

Everaerd D, Klumpers F, Zwiers M, Guadalupe T, Franke B, van Oostrom I, Schene A, Fernandez G, Tendolkar I. Childhood abuse and deprivation are associated with distinct sex-dependent differences in brain morphology. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016;41(7):1716–23.

Ruigrok AN, Salimi-Khorshidi G, Lai MC, Baron-Cohen S, Lombardo MV, Tait RJ, Suckling J. A meta-analysis of sex differences in human brain structure. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2014;39:34–50.

Rossi MA, Basiri ML, McHenry JA, Kosyk O, Otis JM, van den Munkhof HE, Bryois J, Hübel C, Breen G, Guo W, et al. Obesity remodels activity and transcriptional state of a lateral hypothalamic brake on feeding. Science. 2019;364(6447):1271.

Dekkers IA, Jansen PR, Lamb HJ. Obesity, brain volume, and white matter microstructure at MRI: a cross-sectional UK Biobank study. Radiology. 2019;291(3):763–71.

Schumann G, Loth E, Banaschewski T, Barbot A, Barker G, Buchel C, Conrod PJ, Dalley JW, Flor H, Gallinat J, et al. The IMAGEN study: reinforcement-related behaviour in normal brain function and psychopathology. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15(12):1128–39.

Kennedy JT, Astafiev SV, Golosheykin S, Korucuoglu O, Anokhin AP. Shared genetic influences on adolescent body mass index and brain structure: a voxel-based morphometry study in twins. Neuroimage. 2019;199:261–72.

Noble KG, Houston SM, Brito NH, Bartsch H, Kan E, Kuperman JM, Akshoomoff N, Amaral DG, Bloss CS, Libiger O, et al. Family income, parental education and brain structure in children and adolescents. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:773.

Geibprasert S, Gallucci M, Krings T. Addictive illegal drugs: structural neuroimaging. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2010;31(5):803–8.

Opel N, Redlich R, Repple J, Kaehler C, Grotegerd D, Dohm K, Zaremba D, Goltermann J, Steinmann LM, Krughofer R, et al. Childhood maltreatment moderates the influence of genetic load for obesity on reward related brain structure and function in major depression. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2019;100:18–26.

Miller KL, Alfaro-Almagro F, Bangerter NK, Thomas DL, Yacoub E, Xu J, Bartsch AJ, Jbabdi S, Sotiropoulos SN, Andersson JLR, et al. Multimodal population brain imaging in the UK Biobank prospective epidemiological study. Nat Neurosci. 2016;19(11):1523–36.

Van Essen DC, Ugurbil K, Auerbach E, Barch D, Behrens TE, Bucholz R, Chang A, Chen L, Corbetta M, Curtiss SW, et al. The Human Connectome Project: a data acquisition perspective. Neuroimage. 2012;62(4):2222–31.

Bernstein D, Fink L, Bernstein D. Childhood trauma questionnaire: a retrospective self-report manual; 1998.

Goodman R, Ford T, Richards H, Gatward R, Meltzer H. The development and well-being assessment: description and initial validation of an integrated assessment of child and adolescent psychopathology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2000;41(5):645–55.

Newcomb MD, Huba GJ, Bentler PM. A multidimensional assessment of stressful life events among adolescents: derivation and correlates. J Health Soc Behav. 1981;22(4):400–15.

Pausova Z, Paus T, Abrahamowicz M, Almerigi J, Arbour N, Bernard M, Gaudet D, Hanzalek P, Hamet P, Evans AC, et al. Genes, maternal smoking, and the offspring brain and body during adolescence: design of the Saguenay Youth Study. Hum Brain Mapp. 2007;28(6):502–18.

Luo Q, Chen Q, Wang W, Desrivieres S, Quinlan EB, Jia T, Macare C, Robert GH, Cui J, Guedj M, et al. Association of a schizophrenia-risk nonsynonymous variant with putamen volume in adolescents: a voxelwise and genome-wide association study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(4):435–45.

Desrivieres S, Lourdusamy A, Tao C, Toro R, Jia T, Loth E, Medina LM, Kepa A, Fernandes A, Ruggeri B, et al. Single nucleotide polymorphism in the neuroplastin locus associates with cortical thickness and intellectual ability in adolescents. Mol Psychiatry. 2015;20(2):263–74.

Euesden J, Lewis CM, O'Reilly PF. PRSice: Polygenic Risk Score software. Bioinformatics (Oxford). 2015;31(9):1466–8.

Locke AE, Kahali B, Berndt SI, Justice AE, Pers TH, Day FR, Powell C, Vedantam S, Buchkovich ML, Yang J, et al. Genetic studies of body mass index yield new insights for obesity biology. Nature. 2015;518(7538):197–206.

Bycroft C, Freeman C, Petkova D, Band G, Elliott LT, Sharp K, Motyer A, Vukcevic D, Delaneau O, O'Connell J, et al. The UK Biobank resource with deep phenotyping and genomic data. Nature. 2018;562(7726):203–9.

Sotiropoulos SN, Moeller S, Jbabdi S, Xu J, Andersson JL, Auerbach EJ, Yacoub E, Feinberg D, Setsompop K, Wald LL, et al. Effects of image reconstruction on fiber orientation mapping from multichannel diffusion MRI: reducing the noise floor using SENSE. Magn Reson Med. 2013;70(6):1682–9.

Andersson JL, Sotiropoulos SN. Non-parametric representation and prediction of single- and multi-shell diffusion-weighted MRI data using Gaussian processes. Neuroimage. 2015;122:166–76.

Andersson JL, Skare S, Ashburner J. How to correct susceptibility distortions in spin-echo echo-planar images: application to diffusion tensor imaging. Neuroimage. 2003;20(2):870–88.

Andersson JLR, Sotiropoulos SN. An integrated approach to correction for off-resonance effects and subject movement in diffusion MR imaging. Neuroimage. 2016;125:1063–78.

Yeh FC, Wedeen VJ, Tseng WY. Generalized q-sampling imaging. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2010;29(9):1626–35.

Yeh F-C, Verstynen TD, Wang Y, Fernández-Miranda JC, Tseng W-YI. Deterministic diffusion fiber tracking improved by quantitative anisotropy. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e80713.

Glasser MF, Coalson TS, Robinson EC, Hacker CD, Harwell J, Yacoub E, Ugurbil K, Andersson J, Beckmann CF, Jenkinson M, et al. A multi-modal parcellation of human cerebral cortex. Nature. 2016;536:171.

Pauli WM, Nili AN, Tyszka JM. A high-resolution probabilistic in vivo atlas of human subcortical brain nuclei. Scientific Data. 2018;5:180063.

Bernstein DP, Fink L, Handelsman L, Foote J, Lovejoy M, Wenzel K, Sapareto E, Ruggiero J. Initial reliability and validity of a new retrospective measure of child abuse and neglect. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151(8):1132–6.

Opel N, Redlich R, Dohm K, Zaremba D, Goltermann J, Repple J, Kaehler C, Grotegerd D, Leehr EJ, Bohnlein J, et al. Mediation of the influence of childhood maltreatment on depression relapse by cortical structure: a 2-year longitudinal observational study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6(4):318–26.

Bernstein DP, Ahluvalia T, Pogge D, Handelsman L. Validity of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire in an adolescent psychiatric population. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36(3):340–8.

Sotiropoulos SN, Jbabdi S, Xu J, Andersson JL, Moeller S, Auerbach EJ, Glasser MF, Hernandez M, Sapiro G, Jenkinson M, et al. Advances in diffusion MRI acquisition and processing in the Human Connectome Project. NeuroImage. 2013;80:125–43.

Tzourio-Mazoyer N, Landeau B, Papathanassiou D, Crivello F, Etard O, Delcroix N, Mazoyer B, Joliot M. Automated anatomical labeling of activations in SPM using a macroscopic anatomical parcellation of the MNI MRI single-subject brain. Neuroimage. 2002;15(1):273–89.

Smith SM, Nichols TE. Threshold-free cluster enhancement: addressing problems of smoothing, threshold dependence and localisation in cluster inference. Neuroimage. 2009;44(1):83–98.

Marcus DS, Harwell J, Olsen T, Hodge M, Glasser MF, Prior F, Jenkinson M, Laumann T, Curtiss SW, Van Essen DC. Informatics and data mining tools and strategies for the human connectome project. Front Neuroinform. 2011;5:4.

Selig JP, Little TD. Autoregressive and cross-lagged panel analysis for longitudinal data. In: Handbook of developmental research methods. New York: The Guilford Press; 2012. p. 265–78.

Opel N, Redlich R, Kaehler C, Grotegerd D, Dohm K, Heindel W, Kugel H, Thalamuthu A, Koutsouleris N, Arolt V, et al. Prefrontal gray matter volume mediates genetic risks for obesity. Mol Psychiatry. 2017;22(5):703–10.

Gogtay N, Thompson PM. Mapping gray matter development: implications for typical development and vulnerability to psychopathology. Brain Cogn. 2010;72(1):6–15.

Kouneiher F, Charron S, Koechlin E. Motivation and cognitive control in the human prefrontal cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12(7):939–45.

Koechlin E, Hyafil A. Anterior prefrontal function and the limits of human decision-making. Science. 2007;318(5850):594–8.

Tsujimoto S, Genovesio A, Wise SP. Frontal pole cortex: encoding ends at the end of the endbrain. Trends Cogn Sci. 2011;15(4):169–76.

Bludau S, Eickhoff SB, Mohlberg H, Caspers S, Laird AR, Fox PT, Schleicher A, Zilles K, Amunts K. Cytoarchitecture, probability maps and functions of the human frontal pole. Neuroimage. 2014;93(Pt 2):260–75.

Sun X, Kroemer NB, Veldhuizen MG, Babbs AE, de Araujo IE, Gitelman DR, Sherwin RS, Sinha R, Small DM. Basolateral amygdala response to food cues in the absence of hunger is associated with weight gain susceptibility. J Neurosci. 2015;35(20):7964–76.

Stice E, Spoor S, Bohon C, Small DM. Relation between obesity and blunted striatal response to food is moderated by TaqIA A1 allele. Science. 2008;322(5900):449–52.

Burger KS, Stice E. Greater striatopallidal adaptive coding during cue-reward learning and food reward habituation predict future weight gain. Neuroimage. 2014;99:122–8.

Demos KE, Heatherton TF, Kelley WM. Individual differences in nucleus accumbens activity to food and sexual images predict weight gain and sexual behavior. J Neurosci. 2012;32(16):5549–52.

Yokum S, Ng J, Stice E. Relation of regional gray and white matter volumes to current BMI and future increases in BMI: a prospective MRI study. Int J Obes. 2012;36(5):656–64.

Kishinevsky FI, Cox JE, Murdaugh DL, Stoeckel LE, Cook EW 3rd, Weller RE. fMRI reactivity on a delay discounting task predicts weight gain in obese women. Appetite. 2012;58(2):582–92.

Crockett MJ, Braams BR, Clark L, Tobler PN, Robbins TW, Kalenscher T. Restricting temptations: neural mechanisms of precommitment. Neuron. 2013;79(2):391–401.

Neseliler S, Hu W, Larcher K, Zacchia M, Dadar M, Scala SG, Lamarche M, Zeighami Y, Stotland SC, Larocque M, et al. Neurocognitive and hormonal correlates of voluntary weight loss in humans. Cell Metab. 2019;29(1):39–49.e34.

Mann T, Tomiyama AJ, Westling E, Lew AM, Samuels B, Chatman J. Medicare’s search for effective obesity treatments: diets are not the answer. Am Psychol. 2007;62(3):220–33.

Duckworth AL, Tsukayama E, Geier AB. Self-controlled children stay leaner in the transition to adolescence. Appetite. 2010;54(2):304–8.

Schlam TR, Wilson NL, Shoda Y, Mischel W, Ayduk O. Preschoolers’ delay of gratification predicts their body mass 30 years later. J Pediatr. 2013;162(1):90–3.

Scaife JC, Godier LR, Reinecke A, Harmer CJ, Park RJ. Differential activation of the frontal pole to high vs low calorie foods: the neural basis of food preference in anorexia nervosa? Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. 2016;258:44–53.

Horvath TL. The hardship of obesity: a soft-wired hypothalamus. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8(5):561–5.

Neafsey EJ: Chapter 7 Prefrontal cortical control of the autonomic nervous system: anatomical and physiological observations. In: Progress in Brain Research. Volume 85, edn. Edited by Uylings HBM, Van Eden CG, De Bruin JPC, Corner MA, Feenstra MGP: Elsevier; 1991: 147–166.

Clarke RE, Verdejo-Garcia A, Andrews ZB. The role of corticostriatal–hypothalamic neural circuits in feeding behaviour: implications for obesity. J Neurochem. 2018;147(6):715–29.

Hirose S, Osada T, Ogawa A, Tanaka M, Wada H, Yoshizawa Y, Imai Y, Machida T, Akahane M, Shirouzu I, et al. Lateral–medial dissociation in orbitofrontal cortex–hypothalamus connectivity. Front Hum Neurosci. 2016;10:244.

Lemaire JJ, Frew AJ, McArthur D, Gorgulho AA, Alger JR, Salomon N, Chen C, Behnke EJ, De Salles AA. White matter connectivity of human hypothalamus. Brain Res. 2011;1371:43–64.

Kamali A, Zhang CC, Riascos RF, Tandon N, Bonafante-Mejia EE, Patel R, Lincoln JA, Rabiei P, Ocasio L, Younes K, et al. Diffusion tensor tractography of the mammillothalamic tract in the human brain using a high spatial resolution DTI technique. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):5229.

Ganguly P, Brenhouse HC. Broken or maladaptive? Altered trajectories in neuroinflammation and behavior after early life adversity. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2015;11:18–30.

Fuemmeler BF, Dedert E, McClernon FJ, Beckham JC. Adverse childhood events are associated with obesity and disordered eating: results from a U.S. population-based survey of young adults. J Trauma Stress. 2009;22(4):329–33.

Kelly DM, Jones TH. Testosterone and obesity. Obes Rev. 2015;16(7):581–606.

Fragkaki I, Cima M, Granic I. The role of trauma in the hormonal interplay of cortisol, testosterone, and oxytocin in adolescent aggression. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2018;88:24–37.

Ruttle PL, Shirtcliff EA, Armstrong JM, Klein MH, Essex MJ. Neuroendocrine coupling across adolescence and the longitudinal influence of early life stress. Dev Psychobiol. 2015;57(6):688–704.

Hemmingsson E, Johansson K, Reynisdottir S. Effects of childhood abuse on adult obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2014;15(11):882–93.

Val-Laillet D, Aarts E, Weber B, Ferrari M, Quaresima V, Stoeckel LE, Alonso-Alonso M, Audette M, Malbert CH, Stice E. Neuroimaging and neuromodulation approaches to study eating behavior and prevent and treat eating disorders and obesity. NeuroImage Clin. 2015;8:1–31.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Emmanuel Caruyer from the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS), Institute for Research in IT and Random Systems (IRISA), France, for the methodological advices on the analyses of 7-T dMRI data.

IMAGEN consortium (www.imagen-europe.com) authors and affiliations are listed in the supplementary materials.

Funding

Dr. Feng was supported by National Key R&D Program of China (grant 2019YFA0709502). Dr. Luo was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant 2018YFC0910503), National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant 81873909), Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Major Project (grant 2018SHZDZX01), Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai (grant 20ZR1404900), and Zhangjiang Lab. During the preparation of this manuscript, Dr. Luo was a Visiting Fellow at Clare Hall, Cambridge, UK. Dr. Li was partially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 81571031, 81761128035, 81701334, 81703249, and 81930095), Shanghai Municipal Commission of Health and Family Planning (Nos. 2017ZZ02026, 2018BR33, 2017EKHWYX-02, and GDEK201709), Shanghai Shenkang Hospital Development Center (No. 16CR2025B), Shanghai Municipal Education Commission (No. 20152234), Shanghai Committee of Science and Technology (Nos. 17XD1403200, 19410713500, and 18DZ2313505), Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Major Project (No. 2018SHZDZX01), Key projects of Guangdong Province (2018B030335001), Collaborative Innovation Program of Shanghai Municipal Health Commission (2020CXJQ01), National Human Genetic Resources Sharing Service Platform (2005DKA21300), Shanghai Clinical Key Subject Construction Project (shslczdzk02902), and Xinhua Hospital of Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine (2018YJRC03, Talent introduction-014, and Top talent-201603). Dr. Feng was partially supported by the key project of Shanghai Science and Technology Innovation Plan (grant 16JC1420402), the Shanghai AI Platform for Diagnosis and Treatment of Brain Diseases, the Project of Zhangjiang Hi-Tech District Management Committee, Shanghai (grant 2016-17), and the 111 project (grant B18015). This work also received support from the following sources: the European Union-funded FP6 Integrated Project IMAGEN (Reinforcement-related behaviour in normal brain function and psychopathology) (LSHM-CT-2007-037286), the Horizon 2020-funded ERC Advanced Grant “STRATIFY” (Brain network based stratification of reinforcement-related disorders) (695313), ERANID (Understanding the Interplay between Cultural, Biological and Subjective Factors in Drug Use Pathways) (PR-ST-0416-10004), BRIDGET (JPND: BRain Imaging, cognition Dementia and next generation GEnomics) (MR/N027558/1), the FP7 projects IMAGEMEND (602450; IMAging GEnetics for MENtal Disorders) and MATRICS (603016), the Innovative Medicine Initiative Project EU-AIMS (115300-2), the Medical Research Council Grant “c-VEDA” (Consortium on Vulnerability to Externalizing Disorders and Addictions) (MR/N000390/1), the Swedish Research Council FORMAS, the Medical Research Council, the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London, the Bundesministeriumfür Bildung und Forschung (BMBF grants 01GS08152; 01EV0711; eMED SysAlc01ZX1311A; Forschungsnetz AERIAL 01EE1406A, 01EE1406B), the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG project numbers 186318919, 178833530, and 402170461), the Medical Research Foundation and Medical research council (grant MR/R00465X/1), and the Human Brain Project (HBP SGA 2). Further support was provided by grants from the following: ANR (project AF12-NEUR0008-01 - WM2NA, and ANR-12-SAMA-0004), the Fondation de France, the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale, the Mission Interministérielle de Lutte-contre-les-Drogues-et-les-Conduites-Addictives (MILDECA), the Assistance-Publique-Hôpitaux-de-Paris and INSERM (interface grant), Paris Sud University IDEX 2012; the National Institutes of Health, Science Foundation Ireland (16/ERCD/3797), USA (Axon, Testosterone and Mental Health during Adolescence; RO1 MH085772-01A1); and by NIH Consortium grant U54 EB020403, supported by a cross-NIH alliance that funds Big Data to Knowledge Centres of Excellence. Data were provided in part by the Human Connectome Project, WU-Minn Consortium (Principal Investigators: David Van Essen and Kamil Ugurbil; 1U54MH091657) funded by the 16 NIH Institutes and Centers that support the NIH Blueprint for Neuroscience Research, and by the McDonnell Center for Systems Neuroscience at Washington University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

QL has full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. QL, FL, BJS, JF, and TWR conceived and designed the study. EBQ, TJ, TB, ALWB, UB, CB, HF, VF, HG, PG, AH, BI, JLM, MLPM, FN, DPO, LP, SH, JHF, MNS, HW, RW, GS, and SD contributed to data acquisition. QL, LZ, CH, QZ, YY, and SD contributed to data analysis. QL, LZ, CH, YZ, JWK, FL, JF, BJS, SD, and TWR drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to the result interpretation and discussion. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

For the IMAGEN study, the local research ethics committees approved this study and written consent was obtained from participants. When the children were under 18 years old (baseline and first follow-up), the children gave assent and their parents or legal guardian provided written informed consent. The UKB study has obtained ethics approval from the Research Ethics Committee (REC #11/NW/0382) and informed consent from all participants enrolled. The WU-Minn HCP Consortium obtained full informed consent from all participants, and research procedures and ethical guidelines were followed in accordance with the Washington University Institutional Review Boards (IRB #201204036).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Dr. Banaschewski has served as an advisor or consultant to Actelion, Hexal Pharma, Lilly, Lundbeck, Medice, Neurim Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, and Shire. He received conference support or speaker’s fee by Lilly, Medice, Novartis, and Shire. He has been involved in clinical trials conducted by Shire and Vifor Pharma; the present work is unrelated to these relationships. Dr. Walter received a speaker honorarium from Servier (2014). Dr. Sahakian consults for Cambridge Cognition and Peak, UK. Dr. Robbins reports consultancy with Cambridge Cognition, Unilever, Mundipharma, Greenfield Bioventures Inc., research grants from Shionogi, Lundbeck, Small Pharma, royalties for CANTAB from Cambridge Cognition, and editorial honoraria from Elsevier, Springer Verlag, outside the submitted work. The other authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.

Supplementary methods, tables, figures and appendix. Table S1. Demographic characteristics of the participants from the UK Biobank. Table S2. Relationship between childhood abuse and BMI, in male participants in the IMAGEN study. Table S3. Significant clusters after permutation-based TFCE correction, in the male participants from IMAGEN study. Table S4. Relationship between childhood abuse and FPC volume, in male participants in the IMAGEN study. Table S5. Effect size of environmental or genetic risk on BMI, and the significance of difference between the IMAGEN and UK Biobank samples. Table S6. Significant clusters after permutation-based TFCE correction, in the male participants from the UK Biobank. Table S7. Significant clusters after permutation-based TFCE correction, in the female participants from the UK Biobank dataset. Table S9. Predictability of baseline information to BMI change between baseline and follow-up. Figure S1. Hypothalamus defined by the CIT168 atlas. Figure S2. Association between abuse-brain association and abuse-BMI association in females. Figure S3. Structural connectivity of the lateral and the medial hypothalamus. Figure S4. Cross-lagged path analyses between frontopolar volume and BMI in IMAGEN.

Additional file 2: Table S8.

White matter connections between the hypothalamus and the cortical and subcortical areas tracked using the HCP-7T dMRI data with a high spatial resolution.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Luo, Q., Zhang, L., Huang, CC. et al. Association between childhood trauma and risk for obesity: a putative neurocognitive developmental pathway. BMC Med 18, 278 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-020-01743-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-020-01743-2