Abstract

Background

HIV epidemiology among female sex workers (FSWs) and their clients in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region is poorly understood. We addressed this gap through a comprehensive epidemiological assessment.

Methods

A systematic review of population size estimation and HIV prevalence studies was conducted and reported following PRISMA guidelines. Risk of bias (ROB) assessments were conducted for all included studies using various quality domains, as informed by Cochrane Collaboration guidelines. The pooled mean HIV prevalence was estimated using random-effects meta-analyses. Sources of heterogeneity and temporal trends were identified through meta-regressions.

Results

We identified 270 size estimation studies in FSWs and 42 in clients, and 485 HIV prevalence studies in 287,719 FSWs and 69 in 29,531 clients/proxy populations. Most studies had low ROB in multiple quality domains. The median proportion of reproductive-age women reporting current/recent sex work was 0.6% (range = 0.2–2.4%) and of men reporting currently/recently buying sex was 5.7% (range = 0.3–13.8%). HIV prevalence ranged from 0 to 70% in FSWs (median = 0.1%) and 0–34.6% in clients (median = 0.4%). The regional pooled mean HIV prevalence was 1.4% (95% CI = 1.1–1.8%) in FSWs and 0.4% (95% CI = 0.1–0.7%) in clients. Country-specific pooled prevalence was < 1% in most countries, 1–5% in North Africa and Somalia, 17.3% in South Sudan, and 17.9% in Djibouti. Meta-regressions identified strong subregional variations in prevalence. Compared to Eastern MENA, the adjusted odds ratios (AORs) ranged from 0.2 (95% CI = 0.1–0.4) in the Fertile Crescent to 45.4 (95% CI = 24.7–83.7) in the Horn of Africa. There was strong evidence for increasing prevalence post-2003; the odds increased by 15% per year (AOR = 1.15, 95% CI = 1.09–1.21). There was also a large variability in sexual and injecting risk behaviors among FSWs within and across countries. Levels of HIV testing among FSWs were generally low. The median fraction of FSWs that tested for HIV in the past 12 months was 12.1% (range = 0.9–38.0%).

Conclusions

HIV epidemics among FSWs are emerging in MENA, and some have reached stable endemic levels, although still some countries have limited epidemic dynamics. The epidemic has been growing for over a decade, with strong regionalization and heterogeneity. HIV testing levels were far below the service coverage target of “UNAIDS 2016–2021 Strategy.”

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) is one of only two regions where HIV incidence and AIDS-related mortality are rising [1]. Between 2000 and 2015, the increase in the number of new infections was estimated at over a third, while that of AIDS-related deaths, at over threefold [1,2,3]. MENA has been described as “a real hole in terms of HIV/AIDS epidemiological data” [4], with unknown status and scale of epidemics in multiple countries [5,6,7].

Despite recent progress in HIV research and surveillance in MENA [8], including the conduct of integrated bio-behavioral surveillance surveys (IBBSS) [5, 9], many of these data are, at best, published in country-level reports, or never analyzed. Since 2007, the “MENA HIV/AIDS Epidemiology Synthesis Project” has maintained an active regional HIV database [6]. The first systematic syntheses of HIV data documented concentrated and emerging epidemics among men who have sex with men (MSM) [10] and people who inject drugs (PWID) [11]. The majority of these epidemics emerged within the last two decades [10, 11].

Although the size of commercial heterosexual sex networks is expected to be much larger than the risk networks of MSM and PWID [6, 7], estimates for the population proportion of female sex workers (FSWs), volume of clients they serve, and geographic and temporal trends in infection remain to be established. This evidence gap was highlighted in the latest gap report by the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) [3], indicating “a lack of data on the burden of HIV among sex workers in the region” and stressing that “the epidemic among them is poorly understood” though “HIV in every country is expected to disproportionately affect sex workers” [3].

This study characterizes HIV epidemiology among FSWs and their clients in MENA by (1) systematically reviewing and synthesizing all available published and unpublished records documenting population size estimates, population proportions, HIV incidence, and HIV prevalence (including in proxy populations of clients such as male sexually transmitted infection (STI) clinic attendees); (2) estimating, for each population, the pooled mean HIV prevalence per country and regionally; (3) identifying the regional-level associations with prevalence, sources of heterogeneity, and temporal trends; and (4) synthesizing the key measures of sexual and injecting risk behaviors.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

Evidence for population size estimate, population proportion, HIV incidence, and HIV prevalence in FSWs and clients was systematically reviewed as per Cochrane’s Collaboration guidelines [12]. Findings were reported following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [13] (checklist in Additional file 1: Table S1). MENA definition here includes 23 countries extending from Pakistan to Morocco (Additional file 1: Figure S1), based on the convention in HIV research [6, 7, 10, 11] and on World Health Organization (WHO), UNAIDS, and World Bank definitions [6]. MENA was also classified by subregion comprising Eastern MENA (Afghanistan, Iran, Pakistan), the Fertile Crescent (Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, Syria), the Gulf (Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Yemen), the Horn of Africa (Djibouti, Somalia, recently independent South Sudan), and North Africa (Algeria, Libya, Morocco, Sudan, Tunisia).

Systematic searches were performed, up to July 29, 2018, on ten international-, regional-, and country-level databases; abstract archives of International AIDS Society conferences [14]; and Synthesis Project database which includes country-level and international organizations’ reports and routine data reporting [6, 7] (Additional file 1: Box S1). No language or year restrictions were used.

Titles and abstracts of unique citations were screened for relevance, and full texts of relevant/potentially relevant citations were retrieved for further screening. Any document/report including outcomes of interest based on primary data was eligible for inclusion. Case reports, case series, editorials, commentaries, and studies in populations (such as “vulnerable women”) where overlap with FSWs is implied but engagement in sex work is not explicitly indicated were excluded. Reference lists of reviews and all relevant documents were hand searched for eligible reports.

In this article, the term study refers to a specific outcome measure (population size estimate, incidence, or prevalence) in a specific population. Therefore, one report could contribute multiple studies, and one study could be published in different reports. Duplicate study results were included only once using the more detailed report.

Data extraction and synthesis

Data extraction was performed by HC and double extraction by MH, with discrepancies settled by consensus or by contacting authors. Data were extracted from full texts by native speakers (extraction list in Additional file 1: Box S2).

Population size estimates and population proportions were grouped based on being of national coverage or for specific subnational settings, and distinguishing between current FSWs/clients and history of sex work/ex-client. For FSWs, population proportion is defined as the proportion of all reproductive-age women that are engaged in sex work, that is the exchange of sex for money (sex work as a profession) [15, 16], and for clients, as the proportion of men buying sex from FSWs using money. Studies with mixed or non-representative samples (samples biased towards oversampling FSWs with no estimate adjustment) were excluded.

Due to the paucity of studies directly looking at HIV prevalence in clients of FSW, HIV prevalence studies in male STI clinic attendees, or mixed-sex samples of predominantly men (> 60%), were used as a proxy for HIV prevalence in clients of FSWs [17, 18].

Based on meta-analysis results for the pooled HIV prevalence in FSWs, epidemics were classified as concentrated (prevalence > 5%), intermediate-intensity (prevalence between 1 and 5%), and low-level (prevalence < 1%), as informed by epidemiological relevance and existing conventions [19,20,21].

HIV incidence studies were identified and reported. Additional contextual information was extracted from FSW studies included in the review. These include age, age at sexual debut, age at sex work initiation, sex work duration, marital status, and HIV/AIDS knowledge and perception of risk, as well as behavioral measures of condom use, injecting drug use, sexual partnerships, and HIV testing.

Data were summarized using medians and ranges.

Quality assessment

Risk of bias (ROB) assessments for population size estimates/population proportions and for HIV prevalence were conducted as informed by Cochrane Collaboration guidelines [12] (criteria in Additional file 1: Table S2). Briefly, size estimation studies were classified as having “low” versus “high” ROB on each of the three domains assessing the (1) validity of sex work definition/engagement in paid sex (clear/valid definition; otherwise), (2) rigor of estimation methodology (likely-to-yield representative estimate; otherwise), and (3) response rate (≥ 60%; < 60%).

Prevalence studies were similarly classified on each of the four domains assessing the (1) validity of sex work definition/engagement in paid sex (clear/valid definition; otherwise), (2) rigor of sampling methodology (probability-based; non-probability-based), (3) response rate (≥ 60% or ≥ 60% of target sample size reached for studies using respondent-driven or time-location sampling; < 60%), and (4) type of HIV ascertainment (biological assays; self-report).

Studies with missing information for a specific domain were classified as having “unclear” ROB for that domain. Measures only extracted from routine databases were considered of unknown quality, as original reports were not available for assessing ROB, and were not included in the quality assessment. The impact of quality domains on observed prevalence was examined in meta-regression (described below).

Meta-analyses

Pooled mean HIV prevalence in FSWs and client populations were estimated using random-effects meta-analyses, by country and for the whole region. Variances were stabilized using Freeman-Tukey-type arcsine square-root transformation [22, 23]. Weighting was performed using the inverse-variance method [23, 24]. Pooling was performed using Dersimonian-Laird random-effects models to allow for sampling variation and true heterogeneity [25, 26]. Overall prevalence measures were replaced by their stratified measures where applicable.

Heterogeneity was assessed using Cochran’s Q statistic to confirm the existence of heterogeneity, I2 to estimate the magnitude of between-study variation, and prediction intervals to estimate the 95% interval of distribution of true effect sizes [26, 27].

Meta-analyses were implemented in R version 3.4.2 [28].

Meta-regression analyses

Random-effects meta-regression analyses were conducted to identify the regional-level associations with HIV prevalence in FSWs, sources of between-study heterogeneity, and temporal trend. Independent variables considered a priori were country/subregion, FSW population type, sample size, median year of data collection, sampling methodology, response rate, validity of sex work definition, and HIV ascertainment (details in Additional file 1: Table S3). The same factors (as applicable) were considered for clients’ meta-regression analyses.

To avoid the exclusion of studies with zero prevalence, an increment of 0.1 was added to the number of events in all studies to calculate the log-transformed odds, that is prevalence/(1 − prevalence), and corresponding variance [29]. Factors showing strong evidence for an association with the odds (p value ≤ 0.10) in univariable analysis were included in the multivariable analysis.

Meta-regressions were implemented in Stata/SE v.15.1 [30].

Results

Search results and scope of evidence

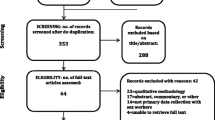

Figure 1 shows the study selection process. A total of 16,131 citations were identified through databases. After excluding duplicates and title and abstract screening, full texts of 336 unique citations were screened, and 87 reports were eligible for inclusion. Hand-searching of reference lists of relevant reports yielded eight additional eligible reports. Searching US Census Bureau and UNAIDS databases yielded 173 additional measures. Sixty-three detailed country-level reports, 11 of which replaced eligible articles, and 134 additional measures were further identified through Synthesis Project database. In sum, data from 147 eligible reports and 307 additional measures were included. These yielded in total 312 size estimation, 6 HIV incidence, and 554 HIV prevalence measures in FSWs and clients.

Flow chart of the study selection process in the systematic review following PRISMA guidelines [13]

Evidence for population size and/or population proportion of FSWs was available for 12 out of 23 MENA countries (270 studies). Population size/population proportion of clients was available in 42 studies from 10 countries. All 6 HIV incidence studies were among FSWs. A total of 485 HIV prevalence studies were identified in 287,719 FSWs from 17 countries and 69 HIV prevalence studies in 29,531 clients (or proxy populations) from 10 countries. Prevalence measures in FSWs and clients contributed respectively 674 and 147 stratified measures for the meta-analyses (overall prevalence measures were replaced by their strata in meta-analyses). For all types of measures, there was a high heterogeneity in data availability across countries.

Population size estimates and population proportions of FSWs and clients

Table 1 and Additional file 1: Table S4 show the population size estimate and population proportion studies for FSWs and clients at the national and subnational levels, respectively. At the national level, the median number of current/recent FSWs (engaged in sex work in the past year) was 58,934 (range = 2218 in Djibouti to 167,501 in Pakistan), and the median population proportion (out of reproductive-age women aged 15–49 years) was 0.6% (range across studies = 0.2% in Egypt to 2.4% in Iran). The median population proportion of current/recent clients (buying sex from FSWs in the past year) based on diverse samples of general population men was 5.7% (range across studies = 0.3% in Sudan to 13.8% in Lebanon).

With high heterogeneity in estimation methodology, time frame, and scope between and within countries, it was deemed not meaningful to generate country-specific or regional-pooled estimates for the size/population proportions.

HIV incidence overview

There were six incidence studies among FSWs (three from each of Somalia and Djibouti; data not shown). Three studies reported zero seroconversions [51, 52]. One study from Somalia reported a cumulative incidence of 2.6% after 6 months of follow-up [51]. The other two from Djibouti—among predominantly Ethiopian FSWs (91%)—reported a cumulative incidence of 3.4% [51] and 11.6% [51] after 3 and 9 months of follow-up, respectively. All incidence studies were conducted before the year 2000 and were limited in scale and scope.

HIV prevalence overview

HIV prevalence in FSWs ranged from 0 to 70%, with a median of 0.1% (Tables 2 and 3 and Additional file 1: Table S5). There was a high heterogeneity, with almost half of the studies (46.8%) reporting zero prevalence. The median prevalence was 0% (range = 0–14%), 2.0% (range = 0–47.1%), and 18.8% (range = 0–70%) in countries with low-level (prevalence < 1%), intermediate-intensity (prevalence 1–5%), and concentrated epidemics (prevalence > 5%), respectively (epidemic classification based on the results of meta-analyses; see below and Table 5). Ranges indicated pockets of higher HIV prevalence, even in countries with low-level and intermediate-intensity epidemics.

In clients/male STI clinic attendees, HIV prevalence ranged from 0 to 34.6%, with a median of 0.4% (Table 4). Studies also showed high heterogeneity with 37.7% reporting zero prevalence. The median prevalence was 0% (range = 0–1.1%), 0.6% (range = 0–9.6%), and 7.4% (range = 0.8–34.6%) in countries with low-level, intermediate-intensity, and concentrated epidemics, respectively. Ranges indicated pockets of higher HIV prevalence in countries with intermediate-intensity epidemics.

Quality assessment

Additional file 1: Tables S6-S9 show the summarized and study-specific quality assessments for the size estimation and HIV prevalence studies in FSWs and clients. Almost all size estimation studies used clear/valid sex work definitions, and > 70% used rigorous size estimation methodologies. Similarly, > 70% of prevalence studies in FSWs used clear/valid sex work definitions and probability-based sampling for participants’ recruitment. Meanwhile, > 85% of prevalence studies in clients used convenience sampling.

Overall, studies were of reasonable quality. The majority of size estimation studies in FSWs and clients had low ROB on ≥ 2 quality domains (94.4% and 82.1%, respectively), and none had high ROB on ≥ 2 domains. Similarly, 85.0% of prevalence studies in FSWs and 39.4% of studies in clients had low ROB on ≥ 2 domains (studies among STI clinic attendees mostly used convenience sampling, and few reported on contact with FSWs), while 0.7% and 6.1% had high ROB on ≥ 2 domains, respectively.

Pooled mean HIV prevalence

The pooled mean HIV prevalence for the MENA region was 1.4% (95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.1–1.8%) in FSWs and 0.4% (95% CI = 0.1–0.7%) in clients (Table 5). A difference was observed between the median prevalence and the pooled mean prevalence due to the high clustering of prevalence measures close to zero.

In FSWs, the national-level pooled mean prevalence was 0 or < 1% in most countries (low-level epidemics); between 1 and 5% (intermediate-intensity epidemics) in Algeria, Libya, Morocco, Somalia, and Sudan; and > 5% (concentrated epidemics) in Djibouti (17.9%, 95% CI = 13.6–22.6%) and South Sudan (17.3%, 95% CI = 8.7–28.1%).

In clients/male STI clinic attendees, the national-level pooled mean prevalence was mostly 0 or < 1%. However, high prevalence was estimated in Djibouti (5.4%, 95% CI = 1.5–10.8%) and South Sudan (13.5%, 95% CI = 4.5–28.8%).

There was evidence for the heterogeneity in effect size (prevalence) in meta-analyses. p value for Cochran’s Q statistic was mostly < 0.0001, prediction intervals were wide, and I2 was often > 50% indicating that most between-study variability is due to the true differences in prevalence across studies rather than chance.

Associations with prevalence, sources of between-study heterogeneity, and temporal trend

Univariable meta-regressions for FSWs demonstrated strong evidence for an association with odds for subregion, population type, sample size, year of data collection, and response rate (Table 6). Meanwhile, there was poor evidence for an association with sampling methodology, validity of sex work definition, and HIV ascertainment, which were hence dismissed from inclusion in the multivariable model. Most variability in odds was explained by subregion (adjusted R2 = 39.8%).

Multivariable analysis indicated strong subregional differences and explained 49.2% of the variation (Table 6). Compared to Eastern MENA, the adjusted odds ratio (AOR) ranged from 0.2 (95% CI = 0.1–0.4) for the Fertile Crescent to 45.4 (95% CI = 24.7–83.7) for the Horn of Africa. Studies with a larger sample size (≥ 100) showed lower odds (AOR = 0.4, 95% CI = 0.2–0.6).

Compared with studies with data collection pre-1993, studies conducted after 2003 showed strong evidence for higher odds (AOR = 2.0, 95% CI = 1.2–3.3). Notably, the trend of increasing odds was evident only after controlling for the strong confounding effect of the subregion. The trend for each subregion was also overall increasing, though the strength of evidence varied across subregions (not shown). Including the year of data collection as a linear term, instead of a categorical variable, using only post-2003 data indicated strong evidence for increasing HIV odds (AOR = 1.15, 95% CI = 1.09–1.21, p < 0.0001; not shown). No association was found with the population type or response rate.

Meta-regression analyses for clients demonstrated similar results to those of FSWs, but with wider CIs considering the smaller number of prevalence studies (Additional file 1: Table S10). There was evidence that subregion was associated with HIV odds in clients, but no evidence that sample size or year of data collection explained the between-study heterogeneity.

Sex work context and sexual and injecting risk behaviors

For the detailed sex work context and behavioral measures, we provide here (for brevity) only a high-level summary of key measures.

Sex work context

Across studies, the mean age of FSWs ranged from 19.5 to 37.4, with a median of 27.8 years. Mean age at sexual debut ranged from 14.0 to 22.5 years (median = 17.5), and mean age at sex work initiation ranged from 17.5 to 27.5 years (median = 22.7). Mean duration of sex work ranged from 0.7 to 14.3 years (median = 5.5). A median of 28.0% (range = 0.9–76.6%) of FSWs were single, 30.1% (range = 0–65.5%) were divorced, and 7.0% (range = 0–27.2%) were widowed.

Reported condom use

There was high heterogeneity in reported condom use among FSWs by sexual partnership type and across and within countries (Additional file 1: Table S11). Condom use at last sex with clients ranged from 1.2 to 94.8% (median = 44.0%). Consistent condom use with clients ranged from 0 to 95.2% (median = 26.3%) among all FSWs and from 38.2 to 45.3% (median = 42.3%) among FSWs reporting condom use with clients.

Median condom use at last sex with regular clients was 55.9% (range = 25.5–92.0%) and that with one-time clients was 58.3% (range = 28.5–96.0%). Less condom use at last sex was found with non-paying partners (median = 22.0%, range = 4.9–78.3%). There was also variability in condom use at last anal sex (range = 0–86.5%), though low levels were generally reported (median = 18.5%).

The median fraction of FSWs who reported having a condom at the time of study interview was 12.5% (range = 0–66.1%).

Clients and partners

Studies varied immensely in types of measures reporting data on clients and partners. Some reported a mean number of regular/non-regular clients, but over various time frames. Others reported different distributions for the number of clients (and by client type), also over various time frames. Summarizing the evidence was therefore challenging, given the large type of measure variability.

This being said, the mean number of clients in the past month ranged from 4.4 to 114.0, with a median of 34.0 clients. Median fraction of FSWs reporting (during the past month) < 5 clients, 5–9 clients, and 10+ clients was 28.5%, 28.1%, and 19.1%, respectively. FSWs were equally likely to report regular and one-time clients during the past month (medians = 80.0% and 81.0%, ranges = 54.3–92.4% and 59.2–97.5%, respectively).

FSWs reported a distribution of sex acts in the past week, with a median of 41.2% reporting 1–2 acts, 32.0% reporting 3–4 acts, and 12.9% reporting 5+ acts. Anal sex with clients in the past month was reported by a median of 8.0% (range = 2.3–100%).

Median fraction of FSWs that are married/cohabiting was 45.3% (range = 0–99.6%), while that of FSWs reporting non-paying partners was 48.5% (range = 6.8–86.2%). The mean number of non-paying partners in the past month ranged between 1 and 3, with about two thirds reporting only one partner.

Only few studies investigated group sex: 7.7% [90] of FSWs reported ever engaging in group sex, 6.2% [68] and 12.9% [68] reported group sex in the past month, and 10.0% [58] in the past week.

Injecting risk behavior, sex with PWID, and substance use

There was a large variability in injecting risk behavior and substance use among FSWs, but the highest levels of injecting drug use were reported in Iran and Pakistan (Additional file 1: Table S12). Median of current/recent injecting drug use was 2.1% (range = 0–26.6%), but the majority of studies were from Pakistan. Studies in Iran reported a history of injecting drug use in the range of 6.1–18.0% (median of 13.6%) among all FSWs and range of 16.4–25.5% (median of 22.3%) among only ever/active drug users. A history of injecting drug use was reported by < 1% (median) of all FSWs (range = 0%–11.8%) in the rest of MENA countries.

Fraction of FSWs reporting current/recent sex with PWID ranged from 0.5 to 13.6% within Afghanistan and 0–54.9% within Pakistan, with medians of 5.2% and 5.6%, respectively. Sex with PWID was reported at 23.6% [93] among FSWs in Iran.

Close to a third of FSWs reported ever using drugs (median = 27.0%, range = 1.7–90.7%). A median of 8.9% reported current/recent drug use (range = 0.6–59.0%). Any substance use before/during sex was reported by 37.8% (median, range = 1.0–88.1%). Alcohol use before/during sex was reported by 44.1% (median, range = 3.0–70.7%).

Knowledge of HIV/AIDS and perception of risk

Knowledge of HIV/AIDS was generally high among FSWs across MENA (Additional file 1: Table S13). Vast majority of FSWs ever heard of HIV (median = 81.9%, range = 25.4–100%) and were aware of sexual (median = 72.0%, range = 50.8–94.9%) and injecting (median = 88.7%, range = 11.5–99.6%) modes of transmission, but to a lesser extent of condoms as a prevention method (median = 51.6%, range = 14.1–89.8%)—condoms were more perceived as a contraception method. Levels of knowledge, however, varied often substantially within the same country.

Overall, FSWs did not perceive themselves at high risk of HIV acquisition (Additional file 1: Table S14). Perception of HIV risk was reported as at-risk (median = 34.6%, range = 22.8–48.5), low-risk (median = 18.3%, range = 7.1–46.9), medium-risk (median = 16.4%, range = 5.3–36.1), and high-risk (median = 14.4%, range = 5.9–32.0).

HIV testing

HIV testing among FSWs varied across countries, but was generally low, with a median fraction of 17.6% (range = 4.0–99.4%) ever tested for HIV (Additional file 1: Table S15). Only a median of 12.1% (range = 0.9–38.0%) of all FSWs tested for HIV in the past 12 months, and nearly two thirds of those who ever tested did so in the past 12 months (median = 59.2%, range = 33.3–82.0%). Majority of FSWs who ever tested were aware of their status (median = 91.9%, range = 60.0–99.0%).

Discussion

Through an extensive, systematic, and comprehensive assessment of HIV epidemiology among FSWs and clients, including data presented in the scientific literature for the first time, we found that HIV epidemics among FSWs have already emerged in MENA, and some appear to have reached their peak. Based on a synthesis and triangulation of evidence from studies on a total of 300,000 FSWs and 30,000 clients, a strong regionalization of epidemics has been identified. In Djibouti and South Sudan, the HIV epidemic is concentrated with a prevalence of ~ 20% in FSWs. In Algeria, Libya, Morocco, Somalia, and Sudan, the epidemic is of intermediate-intensity (prevalence 1–5%). Strikingly, in the remaining countries with available data, the prevalence is < 1%, and most often zero.

A key finding is that HIV prevalence in FSWs has been (overall) growing steadily since 2003. This is the same time in which independent evidence has identified the emergence of major epidemics among both PWID [11] and MSM [10] in MENA. It is probable that the epidemics among these key populations have been bridged to FSWs. An example is Pakistan, where the prevalence among FSWs was < 1% in almost all cities in three consecutive IBBSS rounds between 2005 and 2012 [38, 40, 69]. However, prevalence ranging from 1.5 to 8.8% was documented in half of the cities in the latest round in 2016–2017 [42]. These emerging epidemics among FSWs were preceded by large and growing epidemics first among PWID [11] and then among MSM [10, 11].

Some of the FSW epidemics, particularly those in Djibouti and South Sudan, emerged much earlier, most likely by late 1980s [6], mainly affected by geographic proximity and stronger population links to sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) [6]. Djibouti is a port country and the major trade route for Ethiopia and a station for large international military bases [6, 151]. The majority of FSWs operating in Djibouti are Ethiopians catering to the Ethiopian truck drivers transporting shipments from the Djibouti port [84,85,86]. South Sudan is socio-culturally part of SSA, with a major fraction of FSWs coming from Uganda, Congo, and Kenya [79]. In these MENA countries, HIV in commercial heterosexual sex networks (CHSNs) is well-established and epidemics are concentrated—though at levels lower than the hyper-endemic epidemics observed in SSA [152].

Unlike the epidemics among PWID and MSM [10, 11], the FSW epidemics have been overall growing rather slowly, with the prevalence being mostly < 5%. Strikingly, a considerable fraction of countries still do not appear to have much HIV transmission in CHSNs, with consistently very low prevalence, quite often even at zero level—46.8% of studies in FSWs reported zero prevalence, and 7 out of 18 countries had a pooled mean prevalence of zero or nearly zero. One explanation for the observed low HIV prevalence could be that HIV has not yet been effectively introduced into CHSNs—it took decades for HIV to be effectively introduced into PWID [11] and MSM [10] networks. Another possible factor pertains to the structure of CHSNs, characterized apparently by low connectivity [6, 153, 154], which reduces the risk of HIV being introduced, or efficiently/sustainably transmitted. Unlike PWID and MSM, FSWs are also exposed to HIV mainly through their clients, who have a lower risk of exposure to HIV than themselves, thus possibly contributing to slower epidemic growth [6].

Other factors may also contribute to explaining the observed low HIV prevalence. The synthesized evidence suggests a lower risk environment for FSWs in MENA, compared to other regions. The reported number of clients is rather low at a median of 34 per month, at the lower end of global range [155,156,157,158]. Close to half of commercial sex acts are protected through condom use, with no difference between regular and one-time clients, despite noted variability across and within countries. HIV/AIDS knowledge also varies, but is generally substantial, with the majority of FSWs being aware of sexual and injecting modes of transmission, and over half are aware of condoms as a prevention method. Injecting drug use and sex with PWID is low in most countries, except for countries in Eastern MENA, notably Afghanistan, Iran, and Pakistan. Serological markers for hepatitis C virus (a marker of injecting risk) [159,160,161] are also low in FSWs, assessed at a median of 1.1% (range = 0–9.9%, not shown), with the highest measures reported in Iran [61, 162]. These relatively lower levels of risk behavior than other regions [163,164,165] stand in contrast to what has been observed in PWID and MSM in MENA [10, 11].

Importantly, with the efficacy of 60% in randomized clinical trials [166,167,168,169], male circumcision, which is essentially at universal coverage across MENA [170], may have also slowed, or even substantially reduced HIV transmission in CHSNs leading to the observed low HIV prevalence [171]. Incidentally, the two most affected countries—South Sudan and Djibouti—are nearly the only two major settings where male circumcision is at low coverage in MENA, either nationally, as is the case for South Sudan [170], or among clients of FSWs, as is the case for Ethiopian truckers and international military personnel stationed in Djibouti [151, 170]. Though HIV prevalence will probably continue to increase among FSWs and clients, the high levels of male circumcision coupled with lower levels of risk behavior may prevent significant epidemics, as seen elsewhere [172,173,174], from materializing in CHSNs in multiple MENA countries.

HIV prevalence in FSWs in few countries, particularly in Eastern MENA, may not necessarily reflect heterosexual as much as iatrogenic exposures through injecting drug use. Specifically, in Iran and Pakistan, countries with large HIV epidemics among PWID [11], a considerable fraction of FSWs report current/recent/history (14% in Iran and 2% in Pakistan) of injecting drug use. High prevalence of sex work is also reported in women engaging in injecting drug use [93, 175, 176]. Current/recent/history of sex with PWID is also common (24% in Iran and 6% in Pakistan). The overlap between these key populations suggests a potential for HIV to be bridged from PWID networks to CHSNs, as seem to have occurred in Pakistan recently [42, 177, 178].

Population proportion of current/recent FSWs ranged from 0.2 to 2.4% across studies with a median of 0.6%, while that of current/recent clients ranged from 0.3 to 13.8% with a median of 5.7%, both on the lower end of global range [179, 180]. Though these population proportions may seem small, the size of CHSNs is much larger than that of PWID and MSM [10, 11, 181]. This suggests that CHSNs could be a main driver of HIV incidence in many countries despite the low HIV prevalence in FSWs. An example is Morocco where the mode of transmission analyses estimated that over half of HIV incidence is driven by CHSNs, despite an HIV prevalence of only ~ 2% in FSWs [182,183,184]. The role of CHSNs is even more significant in countries with concentrated epidemics. In Djibouti, for example, the large HIV epidemic among FSWs was mirrored shortly after by a rapid rise in prevalence among clients (as proxied by male STI clinic attendees; Table 4), leading eventually to a prevalence > 1% in pregnant women [6].

HIV response to the epidemic in CHSNs in MENA continues to be weak and limited in scope and scale [185]. Criminality [151, 185] and stigma [186,187,188] associated with sex work persist as barriers to surveillance and targeted programming [189,190,191], leading even to the resistance to acknowledge the existence of sex work [192]. These challenges are compounded by the diverse typologies and increased mobility of FSWs [41, 70, 151]. Across MENA, only 18% of FSWs reported ever testing for HIV, and fewer (12%) reported testing in the past 12 months, far below the 90% service coverage target of “UNAIDS 2016–2021 Strategy” [193]. Programs, including healthcare provision, where they exist, are nearly always implemented by non-governmental organizations (NGOs), who often lack the resources or legal coverage to deliver comprehensive prevention interventions [6, 185].

There are, however, notable exceptions. Morocco has established an evidence-informed national strategy and rapidly scaled up provision of comprehensive services for at-risk populations, including outreach peer education programs as well as testing and case management services [183, 185]. Voluntary counseling and testing centers were established nationwide, with FSWs estimated to constitute about a quarter of attendees in 2007 [183, 194]. Findings of the 2011–2012 IBBSS indicated that over a third of FSWs ever tested for HIV, the vast majority of whom were aware of their status [67]. Condom use at last sex also increased from 37% in 2003 to a median of 50% in 2011 (Additional file 1: Table S11). Morocco’s success has been grounded on a strong multisectorial response where NGOs, in partnership with the government, play a leading role in implementing interventions [185]. In Iran, the large expansion of harm reduction services, including the first women-operated services in MENA [11], is a promising step for targeting FSWs most at risk.

This study is limited by gaps in evidence. Epidemic status among FSWs remains unknown in six countries, as no data were identified. Others (Bahrain and Libya) also had limited data to warrant a meaningful characterization of the epidemic. The high heterogeneity of epidemics within countries suggests that caution is needed when interpreting data without a representative national coverage. For instance, while concentrated epidemics among FSWs are documented in southern Morocco [67, 195] and southern Algeria [113, 196,197,198], these do not appear to be representative of FSWs at the national level [42, 67, 74, 78, 81, 82, 113, 195,196,197,198,199]. Hidden epidemics or outbreaks may also exist in specific geographies within the country, but not necessarily elsewhere. Data varied over time with high quality and volume of evidence available mostly post-2000, thanks to the expansion and funding of IBBSS studies. While the pooled prevalence estimates were meant to provide a summary of the relative standing of MENA countries in the HIV epidemic, the large between-study heterogeneity suggests that caution is warranted when interpreting these estimates. Studies in clients of FSWs/proxy populations remain limited with wide variability in evidence availability across MENA.

A considerable fraction of studies used convenience sampling, although meta-regression indicated no difference in the prevalence by sampling methodology. This may be explained by FSWs being more “visible” [151, 200] compared to PWID [11] and MSM [10]. A sizable fraction of studies was from routine data reporting with no sufficient documentation of study methodology. However, most of these country-level program data were presumably based on rigorous case definitions following WHO guidelines [6]. There is also a possibility that a fraction of studies may have enrolled women without a strict and valid definition for sex work, yet meta-regression findings showed no effect for the validity of sex work definition on HIV prevalence. There was also no evidence that other study-specific quality domains, including HIV ascertainment method and response rate, had an effect on prevalence. A considerable fraction of studies reported zero prevalence, thus an increment of 0.1 was added to a number of events to be able to conduct the meta-regressions. While this choice of increment was arbitrary, other increments yielded the same findings, though some of the effect sizes changed in scale. There was evidence for a small-study effect in meta-regression suggesting potential publication bias towards studies reporting higher prevalence.

Conclusions

HIV epidemics among FSWs are emerging in MENA, with some already established. The epidemic has been growing steadily in recent years, with strong regionalization and heterogeneity. A contributing factor to epidemic growth appears to be the epidemics that emerged among PWID [11] and MSM [10] nearly two decades ago. Strikingly, a large fraction of countries still do not appear to have any significant epidemic dynamics in CHSNs. These findings demonstrate the need for expanding surveillance systems, including the conduct of repeated IBBSS studies with national coverage to monitor HIV prevalence trends and to detect the emergence of epidemics. There is also a pressing need for mapping and size estimation studies to delineate the diverse typologies of sex work and to ensure evidence-informed response with adequate coverage of interventions.

Achieving “UNAIDS 2016–2021 Strategy” [193] service coverage targets entails reaching out to the increasingly dispersed FSW population [41, 70, 151]. Building on Morocco’s success, this would be best achieved through NGOs leading the provision of comprehensive interventions, with governmental support, even if discrete. Extending harm reduction services to women PWID is also critical to curb HIV burden in FSWs most at risk, specifically in Eastern MENA. The window of opportunity for detecting epidemics at their nascence, and for controlling incidence in CHSNs, should not be missed.

Availability of data and materials

All data are within the paper and its supplementary information.

Abbreviations

- AOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratio

- CHSNs:

-

Commercial heterosexual sex networks

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- FSWs:

-

Female sex workers

- IBBSS:

-

Integrated bio-behavioral surveillance surveys

- MENA:

-

Middle East and North Africa

- MSM:

-

Men who have sex with men

- NGOs:

-

Non-governmental organizations

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses

- PWID:

-

People who inject drugs

- ROB:

-

Risk of bias

- SI:

-

Supplementary Information

- SSA:

-

Sub-Saharan Africa

- STI:

-

Sexually transmitted infection

- UNAIDS:

-

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). Global AIDS update 2018. UNAIDS. Geneva; 2018.

The Jointed United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). Global AIDS update 2016. UNAIDS. Geneva; 2016.

The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS): The gap report. UNAIDS. Geneva: 2014.

Bohannon J. Science in Libya. From pariah to science powerhouse? Science. 2005;308(5719):182–4.

Mumtaz GR, Riedner G, Abu-Raddad LJ. The emerging face of the HIV epidemic in the Middle East and North Africa. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2014;9(2):183–91.

Abu-Raddad L, Akala FA, Semini I, Riedner G, Wilson D, Tawil O. Characterizing the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the Middle East and North Africa: time for strategic action. Washington DC: The World Bank Press; 2010.

Abu-Raddad LJ, Hilmi N, Mumtaz G, Benkirane M, Akala FA, Riedner G, Tawil O, Wilson D. Epidemiology of HIV infection in the Middle East and North Africa. Aids. 2010;24(SUPPL. 2):S5–S23.

Saba HF, Kouyoumjian SP, Mumtaz GR, Abu-Raddad LJ. Characterising the progress in HIV/AIDS research in the Middle East and North Africa. Sex Transm Infect. 2013;89(Suppl 3):iii5–9.

Bozicevic I, Riedner G, Calleja JM. HIV surveillance in MENA: recent developments and results. Sex Transm Infect. 2013;89(Suppl 3):iii11–6.

Mumtaz G, Hilmi N, McFarland W, Kaplan RL, Akala FA, Semini I, Riedner G, Tawil O, Wilson D, Abu-Raddad LJ. Are HIV epidemics among men who have sex with men emerging in the Middle East and North Africa?: a systematic review and data synthesis. PLoS Med. 2011;8(8):e1000444.

Mumtaz GR, Weiss HA, Thomas SL, Riome S, Setayesh H, Riedner G, Semini I, Tawil O, Akala FA, Wilson D, et al. HIV among people who inject drugs in the Middle East and North Africa: systematic review and data synthesis. PLoS Med. 2014;11(6):e1001663.

Higgins JPT, Green S, Cochrane collaboration. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Chichester, Hoboken, Wiley-Blackwell; 2008.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

International AIDS Society: Abstract archives of International AIDS Society conferences. Found at: http://www.abstract-archive.org/. Accessed 28 July 2018.

McMillan K, Worth H, Rawstorne P. Usage of the terms prostitution, sex work, transactional sex, and survival sex: their utility in HIV prevention research. Arch Sex Behav. 2018;47(5):1517–27.

The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). Transactional sex and HIV risk: from analysis to action. Available from: http://www.unaidsorg/sites/default/files/media_asset/transactional-sex-and-hiv-risk_en.pdf. 2018.

Gouws E, Cuchi P, International Collaboration on Estimating HIV Incidence by Modes of Trasnmission. Focusing the HIV response through estimating the major modes of HIV transmission: a multi-country analysis. Sex Transm Infect. 2012;88(Suppl 2):i76–85.

Case KK, Ghys PD, Gouws E, Eaton JW, Borquez A, Stover J, Cuchi P, Abu-Raddad LJ, Garnett GP, Hallett TB, et al. Understanding the modes of transmission model of new HIV infection and its use in prevention planning. Bull World Health Organ. 2012;90(11):831–838A.

UNAIDS/WHO working group on global HIV/AIDS and STI surveillance. Guidelines on surveillance among populations most at risk for HIV. Geneva. Available from: http://files.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/epidemiology/2011/20110518_Surveillance_among_most_at_risk.pdf. Accessed Feb 2014: WHO Press; 2011.

Wilson D, Halperin DT. “Know your epidemic, know your response”: a useful approach, if we get it right. Lancet. 2008;372(9637):423–6.

UNAIDS/WHO working group on global HIV/AIDS and STI surveillance. Guidelines for second generation HIV surveillance: an update: know your epidemic. Geneva. WHO Press; 2011. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/85511/9789241505826_eng.pdf;jsessionid=FDD5FD06D64A5A5BE5A6213B15E3A058?sequence=1. Accessed Feb 2014.

Freeman MF, Tukey JW. Transformations related to the angular and the square root; 1950. p. 607–11.

Miller JJ. The inverse of the Freeman–Tukey double arcsine transformation. Am Stat. 1978;32(4):138.

Barendregt JJ, Doi SA, Lee YY, Norman RE, Vos T. Meta-analysis of prevalence. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2013;67(11):974–8.

DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177–88.

Borenstein M. Introduction to meta-analysis. Chichester: Wiley; 2009.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539–58.

R core team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2017.

Say L, Donner A, Gulmezoglu AM, Taljaard M, Piaggio G. The prevalence of stillbirths: a systematic review. Reprod Health. 2006;3:1.

StataCorp. Stata statistical software: release 15.1. College Station: StataCorp LP; 2017.

Bahaa T, Elkamhawi S, Abdel RI, Moustafa M, Shawky S, Kabore I, Soliman C. Gender influence on VCT seeking in Egypt. In: International AIDS society, WEPE0255: 2010; 2010.

Jacobsen J.O. STJ, Loo V. Estimating the size of key affected populations at elevated risk for HIV in Egypt. National AIDS Program, Ministry of Health and Population-Egypt. Cairo 2014.

World Health Organization: HIV surveillance systems: regional update 2011. 2011.

Sharifi H, Karamouzian M, Baneshi MR, Shokoohi M, Haghdoost A, McFarland W, Mirzazadeh A. Population size estimation of female sex workers in Iran: synthesis of methods and results. PLoS One. 2017;12(8):e0182755.

Kahhaleh JG, El Nakib M, Jurjus AR. Knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and practices in Lebanon concerning HIV/AIDS, 1996–2004. East Mediterr Health J. 2009;15(4):920–33.

Bennani A, El Rhilani H, El Kettani A, Latifi A, El Omari B, Alami K, Johnston LG. Estimates of the size of key populations at risk for HIV infection: female sex workers and men who have sex with men, injecting drug users in Morocco in 2013. In: International AIDS Conference, WEPE180: 2014; 2014.

Royaume du Maroc-Ministere de la Sante: Enquete connaissances, attitudes et pratiques des jeunes en matiere d’IST et VIH/SIDA. 2013.

National AIDS Control Program: HIV second generation surveillance in Pakistan: national report round I. Pakistan: Canada-Pakistan HIV/AIDS Surveillance Project; 2005.

Emmanuel F, Blanchard J, Zaheer HA, Reza T, Holte-McKenzie M. The HIV/AIDS Surveillance Project mapping approach: an innovative approach for mapping and size estimation for groups at a higher risk of HIV in Pakistan. Aids. 2010;24(Suppl 2):S77–84.

National AIDS Control Program. HIV second generation surveillance in Pakistan. National Report Round IV 2011. National AIDS Control Program-Pakistan. Islamabad; 2012.

Emmanuel F, Thompson LH, Athar U, Salim M, Sonia A, Akhtar N, Blanchard JF. The organisation, operational dynamics and structure of female sex work in Pakistan. Sex Transm Infect. 2013;89(SUPPL. 2):ii29–33.

National AIDS Control Program. Integrated biological & behavioral surveillance in Pakistan 2016–17: 2nd generation HIV surveillance in Pakistan round 5. National AIDS Control Program-Pakistan. Islamabad; 2017. p. 159.

Projects and Research Department (AFROCENTER GROUP). Baseline study on knowledge, attitudes, and practices on sexual behaviors and HIV/AIDS prevention amongst young people in selected states in Sudan. Sudan National AIDS Control Program, The United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), and The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). Sudan; 2005.

Ministry of Health-Republic of Yemen. Population size estimates among most at risk populations in five major cities in Yemen. Ministry of Public Health-Yemen. Sanaa; 2010.

Todd CS, Barbera-Lainez Y, Doocy SC, Ahmadzai A, Delawar FM, Burnham GM. Prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus infection, risk behavior, and HIV knowledge among tuberculosis patients in Afghanistan. Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34(11):878–82.

Todd CS, Nasir A, Mansoor GF, Sahibzada SM, Jagodzinski LL, Salimi F, Khateri MN, Hale BR, Barthel RV, Scott PT. Cross-sectional assessment of prevalence and correlates of blood-borne and sexually-transmitted infections among Afghan National Army recruits. BMC Infect Dis. 2012;12:196.

Adib SM, Akoum S, El-Assaad S, Jurjus A. Heterosexual awareness and practices among Lebanese male conscripts. East Mediterr Health J. 2002;8(6):765–75.

Royaume du Maroc-Ministere de la Sante, Cooperation Technique Allemande/GTZ: Enquete connaissances, attitudes et pratiques des jeunes concernant les IST et le SIDA; 2007.

Mir AM, Wajid A, Pearson S, Khan M, Masood I. Exploring urban male non-marital sexual behaviours in Pakistan. Reprod Health. 2013;10(1):22.

Sudan National AIDS Control Programme-Federal Ministry of Health. HIV/AIDS/STIs knowledge attitude behavioural and practice among university students and military personnel, Sudan 2004. Sudan National AIDS Control Programme. Khartoum; 2004.

Jama Ahmed H, Omar K, Adan SY, Guled AM, Grillner L, Bygdeman S. Syphilis and human immunodeficiency virus seroconversion during a 6-month follow-up of female prostitutes in Mogadishu, Somalia. Int J STD AIDS. 1991;2(2):119–23.

Constantine NT, Fox E, Rodier G, Abbatte EA. Monitoring for HIV-1, HIV-2, HTLV-I sero-progression and sero-conversion in a population at risk in East Africa. J Egyptian Public Health Assoc. 1992;67(5–6):535–47.

SAR AIDS Human Development Sector-The World Bank. Mapping and situation assessment of key populations at high risk of HIV in three cities of Afghanistan, vol. 23; 2008.

National AIDS Control Program, Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health HIV Surveillance Project. Integrated behavioral & biological surveillance (IBBS) in Afghanistan: year 1 report. National AIDS Control Program-Afghanistan. Kabul; 2010.

National AIDS Control Program, Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health HIV Surveillance Project. Integrated biological & behavioral surveillance (IBBS) in selected cities of Afghanistan: findings of 2012 IBBS survey and comparison to 2009 IBBS survey. National AIDS Control program-Afghanistan. Kabul; 2012.

Ministry of Health, National AIDS Program, Family Health International. HIV/AIDS biological & behavioral surveillance survey round I: summary report. Ministry of Health-Egypt and Family Health International. Cairo; 2006.

Ministry of Health, National AIDS Program, Family Health International, Center for Development Services. HIV/AIDS biological & behavioral surveillance survey round II: summary report. National AIDS Program-Egypt. Cairo; 2010.

Navadeh S, Mirzazadeh A, Mousavi L, Haghdoost A, Fahimfar N, Sedaghat A. HIV, HSV2 and syphilis prevalence in female sex workers in Kerman, south-east Iran; using respondent-driven sampling. Iran J Public Health. 2012;41(12):60–5.

Sajadi L, Mirzazadeh A, Navadeh S, Osooli M, Khajehkazemi R, Gouya MM, Fahimfar N, Zamani O, Haghdoost AA. HIV prevalence and related risk behaviours among female sex workers in Iran: results of the national biobehavioural survey, 2010. Sex Transm Infect. 2013;89(Suppl 3):iii37–40.

Kazerooni PA, Motazedian N, Motamedifar M, Sayadi M, Sabet M, Lari MA, Kamali K. The prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus and sexually transmitted infections among female sex workers in Shiraz, south of Iran: by respondent-driven sampling. Int J STD AIDS. 2014;25(2):155–61.

Moayedi-Nia S, Bayat Jozani Z, Esmaeeli Djavid G, Entekhabi F, Bayanolhagh S, Saatian M, Sedaghat A, Nikzad R, Jahanjoo Aminabad F, Mohraz M. HIV, HCV, HBV, HSV, and syphilis prevalence among female sex workers in Tehran, Iran, by using respondent-driven sampling. AIDS Care. 2016;28(4):487–90.

Mirzazadeh A, Shokoohi M, Khajehkazemi R, et al. HIV and sexually transmitted infections among female sex workers in Iran: findings from the 2010 and 2015 national surveillance surveys. In: 21st International AIDS Conference, Durban, South Africa, 7/18-22, ePoster, Abstract TUPEC175: 2016; 2016.

Karami M, Khazaei S, Poorolajal J, Soltanian A, Sajadipoor M. Estimating the population size of female sex worker population in Tehran, Iran: application of direct capture-recapture method. AIDS Behav. 2017;21:2394–400.

Ministry of Health-Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan: Report to the Secretary General of the United Nations on the United Nations General Assembly Special Session on HIV/AIDS.2014.

Mahfoud Z, Afifi R, Ramia S, Khoury DE, Kassak K, Barbir FE, Ghanem M, El-Nakib M, Dejong J. HIV/AIDS among female sex workers, injecting drug users and men who have sex with men in Lebanon: results of the first biobehavioral surveys. Aids. 2010;24(SUPPL. 2):S45–54.

Valadez JJ, Berendes S, Jeffery C, Thomson J, Ben Othman H, Danon L, Turki AA, Saffialden R, Mirzoyan L. Filling the knowledge gap: measuring HIV prevalence and risk factors among men who have sex with men and female sex workers in Tripoli, Libya. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e66701.

Ministry of Health-Morocco, The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), The Global Fund. HIV integrated behavioral and biological surveillance surveys-Morocco 2011: female sex workers in Agadir, Fes, Rabat and Tanger. Ministry of Health-Morocco. Rabat; 2012.

Bokhari A, Nizamani NM, Jackson DJ, Rehan NE, Rahman M, Muzaffar R, Mansoor S, Raza H, Qayum K, Girault P, et al. HIV risk in Karachi and Lahore, Pakistan: an emerging epidemic in injecting and commercial sex networks. Int J STD AIDS. 2007;18(7):486–92.

National AIDS Control Program-Ministry of Health. HIV second generation surveillance in Pakistan: national report round II. National AIDS Control Program-Pakistan. Islamabad; 2007.

Hawkes S, Collumbien M, Platt L, Lalji N, Rizvi N, Andreasen A, Chow J, Muzaffar R, Ur-Rehman H, Siddiqui N, et al. HIV and other sexually transmitted infections among men, transgenders and women selling sex in two cities in Pakistan: a cross-sectional prevalence survey. Sex Transm Infect. 2009;85(SUPPL. 2):ii8–ii16.

Khan MS, Unemo M, Zaman S, Lundborg CS. HIV, STI prevalence and risk behaviours among women selling sex in Lahore, Pakistan. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:119.

National AIDS Control Program-Pakistan Ministry of Health. Progress report on the Declaration of Commitment on HIV/AIDS for the United Nations General Assembly Special Session on HIV/AIDS. National AIDS Control Program-Pakistan. Islamabad; 2010.

Testa A, Kriitmaa K. HIV & syphilis bio-behavioural surveillance survey (BSS) among female transactional sex workers in Hargeisa, Somaliland. International Organization for Migration (Somaliland) and World Health Organization (Somalia). Hargeisa; 2008.

International Organization for Migration (IOM). Integrated biological and behavioural surveillance survey among vulnerable women in Hargeisa, Somaliland. International Organization for Migration. Geneva; 2017.

Elkarim MAA, AHA, Ahmed S.M., et al: Situation analysis: behavioral & epidemiological surveys & response analysis - HIV/AIDS strategic planning process 2002.

Abdelrahim MS. HIV prevalence and risk behaviors of female sex workers in Khartoum, North Sudan. Aids. 2010;24(SUPPL. 2):S55–60.

Sudan National AIDS Control Programme: UNGASS report 2008–2009, North Sudan.2010.

Sudan National AIDS Control Program: Integrated bio-behavioral HIV surveillance (IBBS) among female sex workers and men who have sex with men in 15 states of Sudan, 2011–2012. 2012.

Government of the Republic of South Sudan-Ministry of Health. A bio-behavioral HIV survey of female sex workers in South Sudan. South Sudan HIV/AIDS Commission. Juba; 2016.

Hsairi M, Ben AS. Enquête sérocomportementale du VIH auprès des travailleuses du sexe clandestines en Tunisie. Ministere de la Sante-Tunisie. Tunis; 2012.

Stulhofer A, Bozicevic I. HIV bio-behavioural survey among FSWs in Aden, Yemen; 2008.

Ministry of Health-Republic of Yemen. UNGASS Country Progress Report 2013. Ministry of Health-Yemen. Sanaa; 2014.

Todd CS, Nasir A, Stanekzai MR, Bautista CT, Botros BA, Scott PT, Strathdee SA, Tjaden J. HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C prevalence and associated risk behaviors among female sex workers in three Afghan cities. Aids. 2010;24(Suppl 2):S69–75.

Rodier GR, Couzineau B, Gray GC, Omar CS, Fox E, Bouloumie J, Watts D. Trends of human immunodeficiency virus type-1 infection in female prostitutes and males diagnosed with a sexually transmitted disease in Djibouti, East Africa. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1993;48(5):682–6.

Couzineau B, Bouloumie J, Hovette P, Laroche R. Prevalence of AIDS infection in target people of the Republic of Djibouti. [French]. Med Trop. 1991;51(4):485–6.

Philippon M, Saada M, Kamil MA, Houmed HM. Attendance at a health center of clandestine prostitutes in Djibouti. [French]. Cahiers Sante. 1997;7(1):5–10.

Marcelin AG, Grandadam M, Flandre P, Nicand E, Milliancourt C, Koeck JL, Philippon M, Teyssou R, Agut H, Dupin N, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma herpesvirus and HIV-1 seroprevalences in prostitutes in Djibouti. J Med Virol. 2002;68(2):164–7.

Sheba MF, Woody JN, Zaki AM, Morrill JC, Burans J, Farag I, Kashaba S, Madkour S, Mansour M. The prevalence of HIV infection in Egypt. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1988;82(4):634.

Watts DM, Constantine NT, Sheba MF, Kamal M, Callahan JD, Kilpatrick ME. Prevalence of HIV infection and AIDS in Egypt over four years of surveillance (1986–1990). J Trop Med Hygiene. 1993;96(2):113–7.

Kabbash IA, Abdul-Rahman I, Shehata YA, Omar AA. HIV infection and related risk behaviours among female sex workers in greater Cairo, Egypt. Eastern Mediterr Health J. 2012;18(9):920–7.

Jahani MR, Alavian SM, Shirzad H, Kabir A, Hajarizadeh B. Distribution and risk factors of hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and HIV infection in a female population with “illegal social behaviour”. Sex Transm Infect. 2005;81(2):185.

Kassaian N, Ataei B, Yaran M, Babak A, Shoaei P, Ataie M. HIV and other sexually transmitted infections in women with illegal social behavior in Isfahan, Iran. Adv Biomed Res. 2012;1:5.

Taghizadeh H, Taghizadeh F, Fathi M, Reihani P, Shirdel N, Rezaee SM. Drug use and high-risk sexual behaviors of women at a drop-in center in Mazandaran Province, Iran, 2014. Iran J Psychiatry Behav Sci. 2015;9(2):49–55.

Asadi-Ali Abadi M, Abolghasemi J, Rimaz S, Majdzadeh R, Shokoohi M, Rostami-Maskopaee F, Merghati-Khoei E. High-risk behaviors among regular and casual female sex workers in Iran: a report from Western Asia. Iran J Psychiatry Behav Sci. 2018; In Press(In Press):e9744.

Naman RE, Mokhbat JE, Farah AE, Zahar KL, Ghorra FS. Seroepidemiology of the human immunodeficiency virus in Lebanon. Preliminary evaluation. L Med J. 1989;38(1):5–8.

Programme National de lutte contre les IST/SIDA, Ministere de la Sante-Royaume du Maroc, Programme National de lutte contre les IST/SIDA. Etude de prevalence des IST chez les femmes qui consultent pour pertes vaginales et/ou douleurs du bas ventre. Ministere de la Sante-Maroc. Rabat; 2008.

Iqbal J, Rehan N. Sero-prevalence of HIV: six years’ experience at Shaikh Zayed Hospital, Lahore. J Pakistan Med Assoc. 1996;46(11):255–8.

Baqi S, Nabi N, Hasan SN, Khan AJ, Pasha O, Kayani N, Haque RA, Haq IU, Khurshid M, Fisher-Hoch S, et al. HIV antibody seroprevalence and associated risk factors in sex workers, drug users, and prisoners in Sindh, Pakistan. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1998;18(1):73–9.

Anwar M, Jaffery G, Rasheed S. Serological screening of female prostitutes for anti-HIV and hepatitis B surface antigen. Pak J Health. 1998;35(3–4):69–73.

Shah AS, Memon MA, Soomro S, Kazi N, Kristensen S. Seroprevalence of HIV, syphilis, hepatitis B and hepatitis C among female commercial sex workers in Hyderabad, Pakistan. Int AIDS Conf. 2004;2004:C12368.

Shah AS, Ghauri AK, Memon MA, Shaikh SA, Abbas SQ, Kristensen S. HIV infection trends in the Sindh Province of Pakistan. In: International AIDS Conference, C12336: 2004; 2004.

Akhtar A, Aslam M, Arif M, Rehman K. Safer sex knowledge and attitude of female sex workers in Pakistan. In: International AIDS Conference, THPE0334: 2008; 2008.

Raza M, Ikram N, Saeed N, Waheed U, Kamran M, Iqbal R, Bakar M. HIV/AIDS and syphilis screening among high risk groups. J Rawal Med Coll. 2015;19(1):11–4.

Jama H, Grillner L, Biberfeld G, Osman S, Isse A, Abdirahman M, Bygdeman S. Sexually transmitted viral infections in various population groups in Mogadishu, Somalia. Genitourin Med. 1987;63(5):329–32.

Burans JP, Fox E, Omar MA, Farah AH, Abbass S, Yusef S, Guled A, Mansour M, Abu-Elyazeed R, Woody JN. HIV infection surveillance in Mogadishu, Somalia. East Afr Med J. 1990;67(7):466–72.

Scott DA, Corwin AL, Constantine NT, Omar MA, Guled A, Yusef M, Roberts CR, Watts DM. Low prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1), HIV-2, and human T cell lymphotropic virus-1 infection in Somalia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1991;45(6):653–9.

Corwin AL, Olson JG, Omar MA, Razaki A, Watts DM. HIV-1 in Somalia: prevalence and knowledge among prostitutes. Aids. 1991;5(7):902–4.

Burans JP, McCarthy M, el Tayeb SM, el Tigani A, George J, Abu-Elyazeed R, Woody JN. Serosurvey of prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus amongst high risk groups in Port Sudan, Sudan. East Afr Med J. 1990;67(9):650–5.

McCarthy MC, Khalid IO, El Tigani A. HIV-1 infection in Juba, southern Sudan. J Med Virol. 1995;46(1):18–20.

Bchir A, Jemni L, Saadi M, Milovanovic A, Brahim H, Catalan F. Markers of sexually transmitted diseases in prostitutes in Central Tunisia. Genitourin Med. 1988;64(6):396–7.

Hassen E, Chaieb A, Letaief M, Khairi H, Zakhama A, Remadi S, Chouchane L. Cervical human papillomavirus infection in Tunisian women. Infection. 2003;31(3):143–8.

Znazen A, Frikha-Gargouri O, Berrajah L, Bellalouna S, Hakim H, Gueddana N, Hammami A. Sexually transmitted infections among female sex workers in Tunisia: high prevalence of Chlamydia trachomatis. Sex Transm Infect. 2010;86(7):500–5.

Ministere de la Sante et de la Population et de la Reforme Hospitaliere, Direction de la Prevention Comite National de Lutte contre les IST/VIH/SIDA. Plan national strategique de lutte contre les IST/VIH/Sida 2008–2012. Programme Commun des Nations Unies sur le VIH/SIDA (ONUSIDA). Geneva; 2009.

Fox E, Haberberger RL Jr, Abbatte EA, Said S, Polycarpe D, Constantine NT. Observations on sexually transmitted diseases in promiscuous males in Djibouti. J Egyptian Public Health Assoc. 1989;64(5–6):561–9.

Organisation Mondiale pour la Sante-Djibouti. Etudes epidemiologiques sur le VIH/SIDA et les IST a Djibouti de 1986 a 2001, Bulletin Epidémiologique Hebdomadaire de l’OMS; 2001. p. 49.

Ministry of Health-Djibouti: Rapport de la Surveillance de l’Infection a VIH par Pasles Sentinelles en Republique de Djibouti, juillet - octobre 1993.1993.

Association Internationale de Developpement (IDA), Ministere de la Sante-Djibouti. Epidemie a VIH/SIDA/IST en Republique de Djibouti Tome I: Analyse de la situation et analyse de la reponse nationale. CREDES. Paris; 2002.

Bortolotti V. Surveillance Sentinelle de L’Infection par le VIH 2006. Organisation Mondiale de la Sante. Djibouti; 2007.

Sadek A, Bassily S, Bishai M, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus and other sexually transmitted pathogens among STD patients in Cairo, Egypt. In: VII International Conference on AIDS, Florence, Italy, 6/16–21, Poster MC3033: 1991; 1991.

Fox E. HIV surveillance in Egypt. The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). Cairo; 1994.

Saleh EE, McFarland W, Rutherford G, et al. Sentinel surveillance for HIV and markers for high risk behaviors. In: XIII International AIDS Conference, Durban, South Africa, 7/9–14, Poster MoPeC2398: 2000; 2000.

Kuwait National AIDS Program: Update UNAIDS epidemiological fact sheet 1999.

Murzi M. Plan to combat AIDS, testing described. Joint Publication Res Serv. 1989;16:17–8.

Al-Owaish RA, Anwar S, Sharma P, Shah SF. HIV/AIDS prevalence among male patients in Kuwait. Saudi Med J. 2000;21(9):852–9.

Alowaish R, Anwar S. Sexually transmitted diseases among bachelor community in Kuwait. Int AIDS Conf. 2002;2002:C11000.

Al-Mutairi N, Joshi A, Nour-Eldin O, Sharma AK, El-Adawy I, Rijhwani M. Clinical patterns of sexually transmitted diseases, associated sociodemographic characteristics, and sexual practices in the Farwaniya region of Kuwait. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46(6):594–9.

Heikel J, Sekkat S, Bouqdir F, Rich H, Takourt B, Radouani F, Hda N, Ibrahimy S, Benslimane A. The prevalence of sexually transmitted pathogens in patients presenting to a Casablanca STD clinic. Eur J Epidemiol. 1999;15(8):711–5.

Manhart LE, Zidouh A, Holmes K, et al. Sexually transmitted disease (STD) in three types of health clinics in Morocco: prevalence, risk factors, and syndromic management. In: XI International Conference on AIDS, Vancouver, 7/7–14, Poster MoC1627: 1996; 1996.

Alami K, Mbarek Ait N, Akrim M, Bellaji B, Hansali A, Khattabi H, Sekkat A, El Aouad R, Mahjour J. Urethral discharge in Morroco: prevalence of microorganisms and susceptibility of gonococcos. East Mediterr Health J. 2002;8(6):794–804.

Ministere de la Sante-Maroc: Etude sur les ecoulements urethraux, prevalence des germes et sensibilite du gonococque aux antibiotiques. 2001.

Khattabi H, Alami K. Surveillance sentinelle du VIH: Resultats 2004 et tendances de la seroprevalence du VIH. Ministere de la Sante-Maroc. Rabat; 2005.

Ministere de la Sante-Royaume du Maroc: Rapport sur les estimations de l’epidemie du VIH/sida au Maroc. 2013.

Abu-Raddad L, Akala FA, Semini I, Riedner G, Wilson D, Tawil O. Characterizing the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the Middle East and North Africa: time for strategic action. Washington DC: The World Bank Press; 2010

Mujeeb SA, Hafeez A. Prevalence and pattern of HIV infection in Karachi. J Pakistan Med Assoc. 1993;43(1):2–4.

Memon GM. Serosurveillance of HIV infection in people at risk in Hyderabad Sindh. J Pak Med Assoc. 1997;47(12):302–4.

National AIDS Programme. HIV seroprevalence surveys in Pakistan. AIDS. 1996;10(8):926–7.

Rehan N. Profile of men suffering from sexually transmitted infections in Pakistan. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2003;15(2):15–9.

Bhutto AM, Shah AH, Ahuja DK, Solangi AH, Shah SA. Pattern of sexually transmitted infections in males in interior Sindh: a 10-year-study. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2011;23(3):110–4.

Razvi SK, Najeeb S, Nazar HS. Pattern of sexually transmitted diseases in patients presenting at Ayub teaching hospital, Abbottabad. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2014;26(4):582–3.

National AIDS Control Program, Balochistan AIDS Control Program, Canada Pakistan HIV/AIDS Surveillance Project. Bio behavioral survey among mine workers in Balochistan, Pakistan. National AIDS Control Program-Pakistan. Islamabad; 2012.

Ismail SO, Ahmed HJ, Grillner L, Hederstedt Issa BA, Bygdeman S. Sexually transmitted diseases in men in Mogadishu, Somalia. Int J STD AIDS. 1990;1(2):102–6.

Duffy G. Report on STD/HIV prevalence study in Somaliland: part 2; 1999.

World Health Organization: The 2004 First National Second Generation HIV/AIDS/STI Sentinel Surveillance Survey Among Pregnant Women Attending Antenatal Clinics, Tuberculosis and STD Patients. 2005.

The United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR). HIV sentinel surveillance among antenatal clients and STI patients in Dadaab refugee camps, Kenya. The United Nations Refugee Agency. Nairobi; 2007.

Ismail A, Ekanem E, Deq S, Arube P, Gboun M. Somaliland 2007 HIV/syphilis sero-prevalence survey: a technical report; 2007.

The Somaliland Puntland and South Central AIDS commissions (NACs): Somalia United Nations General Assembly Special Session on HIV/AIDS country progress report 2010. 2010.

McCarthy MC, Burans JP, Constantine NT, El-Tigani El-Hag AA, El-Saddig El-Tayeb M, El-Dabi MA, Fahkry JG, Woody JN, Hyams KC. Hepatitis B and HIV in Sudan: a serosurvey for hepatitis B and human immunodeficiency virus antibodies among sexually active heterosexuals. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1989;41(6):726–31.

McCarthy MC, Hyams KC, El-Tigani El-Hag A, El-Dabi MA, El-Sadig El-Tayeb M, Khalid IO, George JF, Constantine NT, Woody JN. HIV-1 and hepatitis B transmission in Sudan. Aids. 1989;3(11):725–9.

United States Census Bureau. HIV/AIDS surveillance database. United States Census Bureau. Washington, DC; 2017.

Abdol-Quauder AM. Acute Gonorrhoea in Yemen Republic Epidemiological View. In: VIII International Conference on AIDS in Africa, Marrakech, Morocco, 12/12–16, Abstract TPC080: 1993; 1993.

Jenkins C, Robalino DA. HIV/AIDS in the Middle East and North Africa: the costs of inaction. Washigton, D.C.: The World Bank; 2003.

Awad SF, Abu-Raddad LJ. Could there have been substantial declines in sexual risk behavior across sub-Saharan Africa in the mid-1990s? Epidemics. 2014;8:9–17.

Family Health International, Implementing AIDS Prevention and Care Project (IMPACT). Egypt’s final report April 1999–September 2007 for USAID’s Implementing AIDS Prevention and Care (IMPACT) Project. Family Health International. Arlington; 2007.

Mishwar. An integrated bio-behavioral surveillance study among four vulnerable groups in Lebanon: men who have sex with men; prisoners, commercial sex workers and intravenous drug users. Mid-term report. In: American University of Beirut and World Bank; 2008.

Morison L, Weiss HA, Buve A, Carael M, Abega SC, Kaona F, Kanhonou L, Chege J, Hayes RJ, Study Group on Heterogeneity of HIV Epidemics in African Cities. Commercial sex and the spread of HIV in four cities in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS. 2001;15(Suppl 4):S61–9.

Lau JT, Tsui HY, Siah PC, Zhang KL. A study on female sex workers in southern China (Shenzhen): HIV-related knowledge, condom use and STD history. AIDS Care. 2002;14(2):219–33.

Strathdee SA, Lozada R, Semple SJ, Orozovich P, Pu M, Staines-Orozco H, Fraga-Vallejo M, Amaro H, Delatorre A, Magis-Rodriguez C, et al. Characteristics of female sex workers with US clients in two Mexico-US border cities. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35(3):263–8.

Elmore-Meegan M, Conroy RM, Agala CB. Sex workers in Kenya, numbers of clients and associated risks: an exploratory survey. Reprod Health Matters. 2004;12(23):50–7.

Mumtaz GR, Weiss HA, Vickerman P, Larke N, Abu-Raddad LJ. Using hepatitis C prevalence to estimate HIV epidemic potential among people who inject drugs in the Middle East and North Africa. AIDS. 2015;29(13):1701–10.

Akbarzadeh V, Mumtaz GR, Awad SF, Weiss HA, Abu-Raddad LJ. HCV prevalence can predict HIV epidemic potential among people who inject drugs: mathematical modeling analysis. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):1216.

Mumtaz GR, Weiss HA, Abu-Raddad LJ. Hepatitis C virus and HIV infections among people who inject drugs in the Middle East and North Africa: a neglected public health burden? J Int AIDS Soc. 2015;18:20582.

Kassaian N, Ataei B, Yaran M, Babak A, Shoaei P. Hepatitis B and C among women with illegal social behavior in Isfahan, Iran: seroprevalence and associated factors. Hepat Mon. 2011;11(5):368–71.

Decker MR, Wirtz AL, Baral SD, Peryshkina A, Mogilnyi V, Weber RA, Stachowiak J, Go V, Beyrer C. Injection drug use, sexual risk, violence and STI/HIV among Moscow female sex workers. Sex Transm Infect. 2012;88(4):278–83.

Ouedraogo HG, Ky-Zerbo O, Baguiya A, Grosso A, Goodman S, Samadoulougou BC, Lougue M, Sawadogo N, Traore Y, Barro N, et al. HIV among female sex workers in five cities in Burkina Faso: a cross-sectional baseline survey to inform HIV/AIDS programs. AIDS Res Treat. 2017;2017:9580548.

Isac S, Ramesh BM, Rajaram S, Washington R, Bradley JE, Reza-Paul S, Beattie TS, Alary M, Blanchard JF, Moses S. Changes in HIV and syphilis prevalence among female sex workers from three serial cross-sectional surveys in Karnataka state, South India. BMJ Open. 2015;5(3):e007106.

Auvert B, Taljaard D, Lagarde E, Sobngwi-Tambekou J, Sitta R, Puren A. Randomized, controlled intervention trial of male circumcision for reduction of HIV infection risk: the ANRS 1265 Trial. PLoS Med. 2005;2(11):e298.

Bailey RC, Moses S, Parker CB, Agot K, Maclean I, Krieger JN, Williams CFM, Campbell RT, Ndinya-Achola JO. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in young men in Kisumu, Kenya: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;369(9562):643–56.

Gray RH, Kigozi G, Serwadda D, Makumbi F, Watya S, Nalugoda F, Kiwanuka N, Moulton LH, Chaudhary MA, Chen MZ, et al. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in men in Rakai, Uganda: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2007;369(9562):657–66.

Weiss HA, Quigley MA, Hayes RJ. Male circumcision and risk of HIV infection in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS. 2000;14(15):2361–70.

Morris BJ, Wamai RG, Henebeng EB, Tobian AA, Klausner JD, Banerjee J, Hankins CA. Estimation of country-specific and global prevalence of male circumcision. Popul Health Metrics. 2016;14:4.

Alsallaq RA, Cash B, Weiss HA, Longini IM Jr, Omer SB, Wawer MJ, Gray RH, Abu-Raddad LJ. Quantitative assessment of the role of male circumcision in HIV epidemiology at the population level. Epidemics. 2009;1(3):139–52.

Manopaiboon C, Prybylski D, Subhachaturas W, Tanpradech S, Suksripanich O, Siangphoe U, Johnston LG, Akarasewi P, Anand A, Fox KK, et al. Unexpectedly high HIV prevalence among female sex workers in Bangkok, Thailand in a respondent-driven sampling survey. Int J STD AIDS. 2013;24(1):34–8.

Baral S, Beyrer C, Muessig K, Poteat T, Wirtz AL, Decker MR, Sherman SG, Kerrigan D. Burden of HIV among female sex workers in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12(7):538–49.

Papworth E, Ceesay N, An L, Thiam-Niangoin M, Ky-Zerbo O, Holland C, Drame FM, Grosso A, Diouf D, Baral SD. Epidemiology of HIV among female sex workers, their clients, men who have sex with men and people who inject drugs in West and Central Africa. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16(Suppl 3):18751.

Farmanfarmaee S, Habibi M, Darharaj M, Khoshnood K, Zadeh Mohammadi A, Kazemitabar M. Predictors of HIV-related high-risk sexual behaviors among female substance users. J Subst Abus. 2018;23(2):175–80.

Mirahmadizadeh AR, Majdzadeh R, Mohammad K, Forouzanfar MH. Prevalence of HIV and hepatitis C virus infections and related behavioral determinants among injecting drug users of drop-in centers in Iran. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2009;11(3):325–9.

Melesse DY, Shafer LA, Emmanuel F, Reza T, Achakzai BK, Furqan S, Blanchard JF. Heterogeneity in geographical trends of HIV epidemics among key populations in Pakistan: a mathematical modeling study of survey data. J Glob Health. 2018;8(1):010412.

Melesse DY, Shafer LA, Shaw SY, Thompson LH, Achakzai BK, Furqan S, Reza T, Emmanuel F, Blanchard JF. Heterogeneity among sex workers in overlapping HIV risk interactions with people who inject drugs: a cross-sectional study from 8 major cities in Pakistan. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(12):e3085.

Vandepitte J, Lyerla R, Dallabetta G, Crabbe F, Alary M, Buve A. Estimates of the number of female sex workers in different regions of the world. Sex Transm Infect. 2006;82(Suppl 3):iii18–25.

Carael M, Slaymaker E, Lyerla R, Sarkar S. Clients of sex workers in different regions of the world: hard to count. Sex Transm Infect. 2006;82(Suppl 3):iii26–33.

Blanchard JF, Khan A, Bokhari A. Variations in the population size, distribution and client volume among female sex workers in seven cities of Pakistan. Sex Transm Infect. 2008;84(SUPPL. 2):ii24–7.

Mumtaz GR, Kouyoumjian SP, Hilmi N, Zidouh A, El Rhilani H, Alami K, Bennani A, Gouws E, Ghys PD, Abu-Raddad LJ. The distribution of new HIV infections by mode of exposure in Morocco. Sex Transm Infect. 2013;89(Suppl 3):iii49–56.

Kouyoumjian SP, Mumtaz GR, Hilmi N, Zidouh A, El Rhilani H, Alami K, Bennani A, Gouws E, Ghys PD, Abu-Raddad LJ. The epidemiology of HIV infection in Morocco: systematic review and data synthesis. Int J STD AIDS. 2013;24(7):507–16.

Kouyoumjian SP, El Rhilani H, Latifi A, El Kettani A, Chemaitelly H, Alami K, Bennani A, Abu-Raddad LJ. Mapping of new HIV infections in Morocco and impact of select interventions. Int J Infect Dis. 2018;68:4–12.

Abu-Raddad LJ, Akala FA, Semini I, Riedner G, Wislon D, Tawil O. Policy notes. Characterizing the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the Middle East and North Africa: time for strategic action. Middle Wast and North Africa HIV/AIDS Epidemiology Synthesis Project. World Bank/UNAIDS/WHO publication. Washington (D.C.): The World Bank Press; 2010.

Mohebbi MR. Female sex workers and fear of stigmatisation. Sex Transm Infect. 2005;81(2):180–1.

Dejong J, Mortagy I. The struggle for recognition by people living with HIV/AIDS in Sudan. Qual Health Res. 2013;23(6):782–94.

DeJong J, Mahfoud Z, Khoury D, Barbir F, Afifi RA. Ethical considerations in HIV/AIDS biobehavioral surveys that use respondent-driven sampling: illustrations from Lebanon. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(9):1562–7.

Ministry of Health-Kingdom of Bahrain. UNGASS country progress report - Kingdom of Bahrain: January 2012–December 2013. Ministry of Health-Bahrain. Manama; 2014.